Using sustainability education to enhance a sense of belonging and community among first-year college students

Lewis et all JSE General Fall 2019 Issue PDF

Link to the JSE Fall 2019 General Issue TOC

Abstract

On campuses across the world, faculty, staff, and administrators continue to wrestle with how best to foster a stronger sense of belonging and community among first-year college students. Research in the field of education for sustainability (EfS) suggests that utilizing a cohort-based approach to sustainability education can lead to a number of positive outcomes for participating students and the broader campus culture. Meanwhile, student affairs research demonstrates the value of living/learning communities (LLCs) in supporting undergraduate students as they transition to college. This paper showcases the experience of Hobart and William Smith Colleges in implementing a sustainability-themed LLC on its campus, highlighting how one institution is utilizing sustainability education to build community among first-year college students.

Keywords: sustainability education, living/learning communities (LLCs), first-year education, liberal arts

Introduction

“Sustainability—if it is to exist—has to be felt and practiced” (DeLind & Link, 2004,

p.124).

Every morning we wake up to confront the fact that the fate of our planet is far from certain. Around the world, ‘wicked problems’ abound, leaving many feeling overwhelmed and/or despairing about what it is going to take for us to change course. Research in the field of education for sustainability (EfS) suggests that institutions of higher education are uniquely positioned to forge today’s undergraduate students into the sustainability-minded leaders needed to create a more equitable, just, and, ultimately, hopeful future. One means by which colleges and universities can begin to affect change in their student body is to create spaces for transformative learning to occur. According to Howlett, Ferreira, & Blomfield (2016), this form of learning allows us “to integrate, connect, confront and reconcile multiple ways of looking at the world” (p.307). Arguably, we can enhance the power of transformative learning by taking advantage of a cohort-based approach to sustainability education. Recent research suggests “the culture of a community of practice engaged in sustainability education can be an antidote to debilitating pessimism” (McClam et al., 2015, n.p.) brought about by higher education’s often acute focus on the origins and impacts of wicked problems rather than how best to solve these issues. In other words, cultivating sustainability-oriented communities for practice allows for the development of ‘clear-eyed hope’, or the type of hope (and agency) that emerges when one understands “the depth and breadth of the challenges faced” (Evans, 2015, n.p.) but still chooses to act anyway (see also McClam et al., 2015).

Our ability to forge sustainability-oriented communities of practice on college campuses is also likely contingent on us embracing the fact that much of what students learn while in college does not happen in the classroom. As such, Barth et al. (2007) argue that “learning environments should be designed in a way that…enable[s] informal, …unconscious learning” (p.421) to proliferate. While faculty often encourage their students to continue learning after leaving the classroom, we can further our efforts to develop the type of cultural shifts we desire by working alongside student affairs personnel to develop and implement sustainability-themed living/ learning communities (LLCs). By combining curricular, co-curricular, and residential components to encourage cohort-based exploration and collaboration of important topics such as sustainability, LLCs can foster “a high quality and enduring educational experience” (Stassen, 2003, p.585) for the students, faculty, and staff participating in these intentional communities. Arguably, the most effective LLCs “capitalize on community settings to create opportunities for learning wherever and whenever it occurs” (Katz, 2015, p.3). Simultaneously, LLCs foster intentional overlaps between students’ academic and social lives, fostering an environment in which students can better integrate into the social fabric of a college and intentionally cultivate connections between academic and personal experiences (Gerdes & Mallinckrodt, 1994).

In the pages that follow, we highlight how Hobart and William Smith Colleges, a small liberal arts college situated in the Finger Lakes region of upstate New York, is utilizing a sustainability-themed LLC to build community among first-year students on its campus. We first provide a brief overview of the Sustainable Living and Learning Community (SLLC) Program before transitioning into a discussion of our study approach and preliminary findings. We close by reiterating that sustainability-themed LLCs have the potential to not only build stronger partnerships between academic affairs and student affairs but also enhance our students’ ability to integrate their academic and social lives in ways that may ultimately lead them to affect positive change in the world.

Our Program

Each fall since 2014, the 42 to 58 first-year students who report an interest in sustainability on their academic intake forms join the SLLC Program at Hobart and William Smith Colleges. Upon arriving on campus, SLLC students move into traditional, corridor-style housing in an all gender residence hall situated next door to the Environmental Studies offices. On each floor of the residence hall, SLLC students have access to a hybrid study/social space, where for 85 minutes at a time, faculty members from the Environmental Studies (ES) Program join a group of 14 to 16 SLLC students for twice weekly class meetings. The fall semester class, a first-year seminar entitled “Sustainable Living and Learning,” asks students to (re)examine the relationship between sustainability and consumption across space and time through engagement in a guided exploration of sustainability topics such as waste, food, and sense of place. Fall assignments range from low-stakes reading responses and reflective journals to a more substantial academic research project analyzing the impacts of everyday objects/products such as plastic microbeads or coffee. In comparison with other LLCs that include only a one-semester commitment, the SLLC student experience spans a full academic year. In the spring semester “Campus Sustainability” course, SLLC students continue to investigate the challenges of sustainable consumption through completing units on climate change, energy, and water. Students continue to complete reading responses and reflective journals while the focus of the students’ research efforts shifts toward enhancing sustainability efforts on the HWS campus. Completed in teams of two to four students, the campus sustainability intervention project centers on the identification of a campus sustainability issue and the development of an evidence-based proposal for how best to address this issue. Meanwhile, each semester includes a series of experiential learning activities—completed during a common 85- to 165-minute lab period—that bolster the SLLC Program’s course content. Designed to bring abstract sustainability concepts to life in more concrete ways, these activities include regular visits to the campus farm, personal sustainability experiments such as waste and closet audits, and field trips to the local farmer’s market, a nearby landfill, and a fracking site in an adjacent state. For a more detailed description of the SLLC Program and its approach to sustainability education, see Lewis et al. (2019).

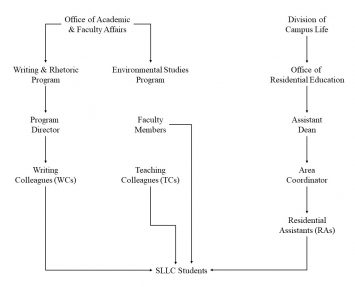

Research shows that collaboration between academic and student affairs is central to the success of LLCs on college campuses (Messineo, 2012). Therefore, as the first multi-semester LLC implemented at Hobart and William Smith Colleges, institutional support for the SLLC Program is significant (Figure 1), bringing faculty, administrators, and more experienced undergraduate students from across campus together to actively support SLLC students as they transition to college. Each year, depending on staffing capabilities and resource availability, two to four ES faculty members, who initially received modest financial stipends for their leadership in the Program, teach the linked fall and spring courses while also serving as SLLC students’ academic advisors. In the classroom, SLLC faculty often work alongside a team of undergraduate peer mentors—teaching colleagues (TCs) and writing colleagues (WCs)—who serve as academic and co-curricular role models to our students. In addition to gaining leadership experience, our undergraduate collaborators are offered course credit for their contributions to the SLLC Program. The SLLC team also includes professional staff from the Division of Campus Life and Office of Residential Education—live-in residence life staff, the director of

Figure 1 Administrative structure for the first three years of the Sustainable Living and Learning Community (SLLC) Program at Hobart and William Smith Colleges (adapted from Lewis et al., 2019).

residential education, and the assistant vice president for campus life—provide expertise on how best to capitalize on the social environment provided in SLLC to enhance the students’ academic experiences. In addition, the SLLC Program’s team of professional staff works alongside faculty and student leaders to host co-curricular events that brings course concepts to life in the residence hall. For instance, undergraduate residential assistants (RAs) work alongside TCs to host co-curricular events such as clothing swaps, applesauce making, etc. that seamlessly integrate the principles of sustainability into residence hall programming. The team—faculty, staff, and undergraduate peer mentors— meets monthly to discuss student life, community development, and other programmatic endeavors.

Our Assessment Approach

In order to assess the impacts of the SLLC Program on first-year students and their sense of belonging, we utilize the Quality of Campus Experience survey (QCE), an internal assessment instrument developed by the HWS Division of Campus Life and Office of Residential Education in anticipation of the implementation of LLCs on our campus. Administered during a two-week period at the end of each spring semester, the QCE survey is comprised of twenty 5-point Likert scale questions (from 1= strongly disagree to 5= strongly agree) designed to measure student engagement and satisfaction across four domains:

- Social: Questions in the first domain analyze students’ level of satisfaction across six areas: enjoyment of hall activities, class-based interactions with other hall residents, active participation in hall activities, quantity of social activities offered in the residence hall, formation of long-lasting relationships with fellow hall members, and establishment of new friendships.

- Skills: The questions in the second domain assess students’ self-reported skills across five different areas: the ability to make positive decisions, awareness of on-campus resources, understanding of their contributions to the campus community, ability to be inclusive of others from diverse backgrounds, and understanding of the value of others’ opinions.

- Academic Environment: Questions in the third domain evaluate students’ perceptions of the residence hall’s academic environment across four areas: ability to hold peers accountable, peers’ sensitivity to quiet hours, ability to study in one’s room, and overall satisfaction with the noise level.

- Satisfaction: Questions in the fourth domain measure the students’ level of overall satisfaction across five areas: quality of living environment, enjoyment of living environment, ability to be involved on campus, the availability of off-campus community engagement opportunities, and quality of study/social spaces on campus.

The study population for this study is the 1,869 students matriculating to HWS between 2014 and 2016 and commencing their undergraduate studies in August (Table 1). During the first three years of the SLLC Program, 28.1% of first-year students at Hobart and William Smith Colleges completed our survey. Notably, response rates ranged from 19.8% in Year 3 to 42.9% in Year 1. We attribute our declining response rate to our decision to shift from administering the QCE survey on paper during floor meetings in Year 1 to online survey administration in Years 2 and 3.

In order to compare how SLLC students performed on the QCE survey relative to other first-year students at the Colleges, we stratified our sample into three subpopulations. The first

Table 1 Number of survey respondents for the Colleges’ Quality of Campus Experience (QCE) Survey by subpopulation over the three-year study period.

| Academic year | Study population

(# matriculated students) |

Subpopulations

(# matriculated students) |

||

| SLLC | Control Group | Non-SLLC | ||

| 2014-2015 | 648 | 40 | 60 | 278 |

| 2015-2016 | 635 | 10 | 11 | 131 |

| 2016-2017 | 586 | 15 | 9 | 116 |

subpopulation is comprised of the 65 respondents enrolled in the SLLC Program. The second subpopulation—the control group—is comprised of subset of 80 non-SLLC respondents with a similar gender makeup to the SLLC group who, like our students, live in traditional, corridor-style housing in an adjacent co-ed residence hall. The remaining first-year students who completed our survey comprise our third subpopulation—the non-SLLC group. These 525 first-year students also lived in traditional, corridor-style housing in either co-ed or single sex residence halls. Notably, neither the control group nor the non-SLLC group had access to hybrid social/study spaces similar to those available to SLLC students.

Due to variable response rates across the study period, we opted to aggregate all three years of QCE data into a single data set stratified by subpopulation. We then analyzed our data

using descriptive statistics, calculating average scores (means) for each subpopulation on each of the survey’s twenty items. Given the preliminary nature of this study, we limited the scope of our initial analyses to determining how mean scores for the SLLC group compared to those of the control and non-SLLC groups.

Our Preliminary Findings

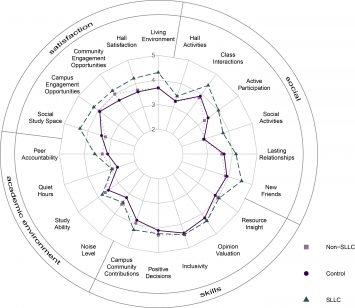

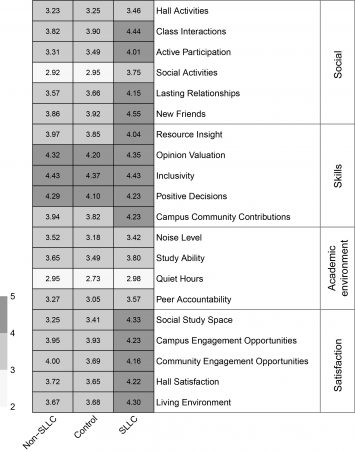

Over the course of the first three years of the SLLC Program, SLLC students consistently outperformed the control group in all 20 areas of student engagement and satisfaction assessed in this study (Figures 2 and 3). The SLLC group also consistently outperformed the non-SLLC group on 17 of 20 items included on the QCE survey (Figure 2). Notably, differences between the SLLC and non-SLLC group means on these three items were 0.10 points or less (Figure 3), suggesting nominal differences between the two groups in these particular areas of student engagement and satisfaction.

Figure 2 A comparison of three year average student engagement and satisfaction scores from the Quality of Campus Experience (QCE) by subpopulation

The largest average difference in means between the three subpopulations occurred in the social domain (Figure 2), in which SLLC students outperformed both the control and non-SLLC groups on all six items in this domain (Figure 3). For example, SLLC students indicated higher average levels of agreement with the “I have met many new friends in the residence hall” statement (A=4.55) than either the control (A=3.92) or non-SLLC (A=3.86) groups. Similarly, the SLLC group reported greater agreement on the “I have formed long-lasting relationships with fellow hall members” question (A=4.15) than both the control group (A=3.66) and non-SLLC group (A=3.57). When compared to other first-year students, students in the SLLC group, on average, also reported higher levels of agreement with the following statements: “Generally, I feel like an active participant in the hall” (A=4.01); and, “I interact with students from my residence hall in classes” (A=4.44).

Another area in which the SLLC group reliably outperformed students in the control and non-SLLC groups was in the overall satisfaction domain (Figure 2). The largest observed difference between SLLC students and their peers occurred in the overall level of satisfaction each group expressed with their respective living environments (Figure 3). SLLC students indicated higher average levels of agreement with the “I enjoyed the type of living environment I was assigned or selected” statement (A=4.30) than either the control group (A=3.68) or the non-SLLC group (A=3.67). While the control and non-SLLC groups appeared more neutral with regard to their overall satisfaction concerning their time in the residence hall (A=3.65 and A=3.72, respectively), the SLLC group reported a higher average hall satisfaction (A=4.22). Given that only SLLC students had access to hybrid social/study spaces in the residence hall, it is also worth noting that SLLC students reported much higher average levels of agreement with the statement “I like the amount of social space in my residence hall” (A=4.33) than either the control (A=3.41) or the non-SLLC (A=3.25) groups.

Meanwhile, SLLC students, on average, did not consistently outperform the control or non-SLLC groups in either the skills or academic environment domains during the three-year study period (Figure 2). When considering the skills domain, the SLLC group did report slightly higher average levels of agreement with three out of five statements (i.e., opinion valuation, campus community contributions, and resource insight) (Figure 3). SLLC students reported nearly equal levels of agreement with the “I’m inclusive to students from diverse backgrounds” statement (A=4.43) as the non-SLLC group (A=4.43) and but slightly higher levels of agreement than the control group (A=4.37). A similar pattern emerged with regard to how each of the three subpopulations rated their level of agreement on the “I have the tools to make positive decisions for myself” item on the survey instrument (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Three year average student engagement and satisfaction scores from the Quality of Campus Experience (QCE) survey for our three subpopulations organized by domain. Darker shades of gray indicate higher levels of agreement with a given survey item.

With regard to the academic environment domain, the SLLC group reported slightly higher average levels of agreement than both the control and non-SLLC groups on three out of four items assessed by the QCE survey (i.e., study ability, quiet hours, and peer accountability) (Figure 3). While SLLC students reported a slightly lower average level of agreement with the following statement: “The noise level on the floor is acceptable” (A=3.42) than the non-SLLC group (A=3.52), the SLLC group mean for this item still exceeded that of the control group (A=3.18).

Key Take-Aways and Next Steps

Research in both EfS and student affairs suggests that undergraduate students arrive on campus eager to feel like a part of something bigger. The benefits of LCs for first-year students’ transition to college and integration into the social and academic lives of the undergraduate experience is well-researched (Stassen, 2003; Tinto, Love, & Russo, 1994). One means by which to not only enhance students’ sense of belonging, but to restructure sometimes competing social and academic experiences, is to utilize a residential, cohort-based approach to sustainability education. As Stassen (2003) points out, the residential component is additive to the benefits of the cohort-based approach. Our experience implementing a sustainability-themed LLC on the Hobart and William Smith Colleges’ campus suggests that programs that more intentionally integrate the curricular, co-curricular, and residential components of undergraduate students’ experience can be quite effective in building community, particularly among first-year college students.

Not only did SLLC students consistently outperform their peers with regard to forming new friendships and forging long-lasting relationships with their fellow hall members, but our students also reported that they felt like active participants in the hall. We interpret these findings as lending support to the argument that sustainable education can and should build community on college campuses. To bolster this argument, a cursory review of annual data compiled since the Colleges expanded its first-year program to include other thematically-focused LLCs (now known as the LLC Program) shows that differences in the scores of LLC students and non-LLC students were less remarkable than the differences in scores observed between SLLC and non-SLLC students. Moreover, when subgroups that measure LLC data by theme are created, the SLLC subgroup indicates that our sustainability-themed LLC continues to foster better social outcomes than any other LLC implemented on our campus to date. One could infer that the residentially-themed projects where students utilize their living arrangement as a living laboratory, such as the SLLC Program, better assist students in more easily connecting their academic experiences with their everyday lives as students.

The academic environment and skills-based outcomes of the SLLC Program, by comparison, are less clear. While we are already successful in encouraging peer accountability and study ability in the residence hall, our students still reported struggling to integrate their academic and social lives in consistently productive ways. For instance, SLLC students reported being less satisfied by the noise level in their residence hall than their peers did, an outcome that did not surprise or otherwise alarm us. After all, we intentionally set out to create a vibrant community of practice that provides students with the tools necessary to make positive decisions and affect change in both their academic and social lives. As we continue to tweak the SLLC Program and its structure and curriculum, we remain hopeful that additional program benefits will accrue. As Stassen (2003) points out, however, self-selection bias is an important consideration when evaluating the impacts of LLCs, particularly in cases where institutions allow students to choose whether to participate in or opt out of a LLC.

Beyond its positive student outcomes, the SLLC Program is also spurring efforts to reimagine the first-year student experience at the Colleges. Prior to the first cohort of SLLC students arriving on campus in fall 2014, faculty and staff rarely had the opportunity to interact, let alone build and administer a program together. In addition, there were few institutional structures in place to encourage greater levels of intersection between students’ academic and social lives. The SLLC Program’s early successes continue to inspire new partnerships between Academic Affairs and Campus Life. Recent renovations of several other first-year residence halls mean that we can now support up to 12 LLCs of various size and configurations each year. As a result, more HWS students than ever have the opportunity to participate in a themed community of practice if they so choose. Meanwhile an increasing number of faculty are actively collaborating with colleagues in Campus Life, namely the Office of Residential Education, to develop innovative curricular, co-curricular, and residential programming for our students.

While we have yet to conclude that the SLLC Program is achieving all of its initial goals, we are encouraged by what we have been able to achieve in three short years. In addition to being able to foster a stronger sense of belonging and community among first-year students using sustainability education, we are beginning to witness the ways in which increasing opportunities for faculty-staff collaboration can enhance the quality of everyone’s campus experiences.

References

Barth, M., Godemann, J., Rieckmann, M., & Stoltenberg, U. (2007). Developing key competencies for sustainable development in higher education. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 8(4), 416-430.

Evans, T.L. (2015). Finding heart: Generating and maintaining hope and agency through sustainability education. Journal of Sustainability Education, 10. Retrieved from http://www.jsedimensions.org/wordpress/content/finding-heart-generating-and maintaining-hope-and-agency-through-sustainability-education_2015_11/

Delind, L.B. & Link, T. (2004). Place as the nexus of a sustainable future: A course for all of us. In P.F. Bartlett & G.W. Chase (Eds.), Sustainability on Campus: Stories and Strategies for Change (pp.121-137). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Gerdes, H. and Mallinekrodt, B. (1994). Emotional, social, and academic adjustment of college students: A longitudinal study of retention. Journal of Counseling and Development, 72(3), 281-288.

Howlett, C., Ferreira, J.-A., & Blomfield, J. (2016). Teaching sustainable development in higher education: Building critical, reflective thinkers through an interdisciplinary approach. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 17(3), 305-321.

Lewis, R.A., Kenerson, M.J., Sorrentino, C., and Rowse, T.H. (2019). Experiencing sustainability education: Insights from a living and learning programme. Journal of Education for Sustainable Development, 13(1), 14-24.

McClam, S., Cass, A., Connors, C., Frawley, D., McPartin, A., Orifici, C., & Papernik, L. (2015). Collaboratively creating and sustaining hope and agency. Journal of Sustainability Education, 10. Retrieved from http://www.susted.com/wordpress/content/collaboratively-creating-and-sustaining-hope-and-agency_2015_12/

McClam, S., Cass, A., Connors, C., Frawley, D., McPartin, A., Orifici, C., & Papernik, L. (2015). Collaboratively creating and sustaining hope and agency. Journal of Sustainability Education, 10. Retrieved from http://www.susted.com/wordpress/content/ collaboratively-creating-and-sustaining-hope-and-agency_2015_12/

Stassen, M.L.A. (2003). Student outcomes: The impact of varying living-learning community models. Research in Higher Education, 44(5), 581-613.

Tinto, V., Love, A. G., & Russo, P. (1994). Building Learning Communities for New College Students: A Summary of Research Findings of the Collaborative Learning Project, University Park, PA: National Center for Postsecondary Teaching, Learning, and Assessment.

Robin A. Lewis, Ph.D. is Assistant Professor of Environmental Studies and Chair of Sustainable Community Development at Hobart and William Smith Colleges. Dr. Lewis teaches courses on sustainable consumption, human/environment interactions, and community-based research. Her research focuses on fostering agency and activism through sustainability education, as well as the development and implementation of forest certification in Peninsular Malaysia. lewis@hws.edu

Robin A. Lewis, Ph.D. is Assistant Professor of Environmental Studies and Chair of Sustainable Community Development at Hobart and William Smith Colleges. Dr. Lewis teaches courses on sustainable consumption, human/environment interactions, and community-based research. Her research focuses on fostering agency and activism through sustainability education, as well as the development and implementation of forest certification in Peninsular Malaysia. lewis@hws.edu  Brandon B. Barile, Ed.D. is Assistant Vice President for Campus Life and Dean of Student Engagement and Conduct at Hobart and William Smith Colleges where Dr. Barile has taught within the LGBT Studies Program and offers courses on personal, peer, and community empowerment. As a scholar, their research centers on queer leadership within student affairs. barile@hws.edu

Brandon B. Barile, Ed.D. is Assistant Vice President for Campus Life and Dean of Student Engagement and Conduct at Hobart and William Smith Colleges where Dr. Barile has taught within the LGBT Studies Program and offers courses on personal, peer, and community empowerment. As a scholar, their research centers on queer leadership within student affairs. barile@hws.edu  Thomas E. Drennen, Ph.D. is a Professor of Economics and Environmental Studies and Chair of Entrepreneurial Studies at Hobart and William Smith Colleges. His research and teaching focuses on the economic and environmental tradeoffs associated with various energy pathways. drennen@hws.edu

Thomas E. Drennen, Ph.D. is a Professor of Economics and Environmental Studies and Chair of Entrepreneurial Studies at Hobart and William Smith Colleges. His research and teaching focuses on the economic and environmental tradeoffs associated with various energy pathways. drennen@hws.edu  Robert Beutner, MA, GISP is a Digital Learning Consultant and a member of the Digital Learning Team of IT Services at Hobart and William Smith Colleges. He supports the integration of geospatial and data visualization technologies into teaching, learning, and research. beutner@hws.edu

Robert Beutner, MA, GISP is a Digital Learning Consultant and a member of the Digital Learning Team of IT Services at Hobart and William Smith Colleges. He supports the integration of geospatial and data visualization technologies into teaching, learning, and research. beutner@hws.edu