HEAD, HEART AND HANDS MODEL FOR TRANSFORMATIVE LEARNING: PLACE AS CONTEXT FOR CHANGING SUSTAINABILITY VALUES

Table of Contents: JSE March 2015 — Sustainability: What’s Love Got to Do with It?

PDF: Singleton JSE March 2015 Love Issue

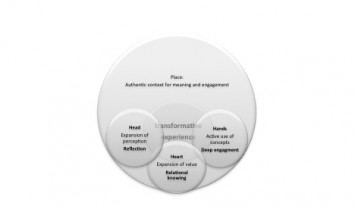

Abstract: This conceptual article presents the Head, Heart and Hands Model for Transformational Learning. The model was conceptualized from a synthesis of diverse literature, such as sustainable education, transformative learning theories, placed-based learning, indigenous learning approaches, experiential learning, eco-literacy, curriculum theory and conceptual change in science classes. Transformative processes are necessary to change the prevalent anthropocentric eco-paradigm of western culture toward more sustainable values and behaviors. Head, hand and heart is a holistic approach to developing ecoliteracy introduced by Orr (1992) and expanded by Sipos, Battisti and Grimm (2008). The model shows the holistic nature of transformative experience and relates the cognitive domain (head) to critical reflection, the affective domain (heart) to relational knowing and the psychomotor domain (hands) to engagement. Pugh’s (2002) pragmatic construct of transformational learning experience offers an analytic tool for measuring transformational experiences through expanded perception (cognitive), expanded value (affective) and active use of learned concepts (psycho-motor). This model not only represents the multi-dimensional nature of transformative processes, it also includes the importance of learning context. The context of place provides a framework of authentic experience for deeper reflection, sense of belonging and body/sensory stimulation that acts as a catalyst for deep engagement required for transformation. Literature in the domain areas are discussed as well as the importance of nature connection and love of place to sustainability values and pro-environmental behaviors.

Keywords: Sustainability values, transformational learning, nature-connectedness, ecoliteracy, head, heart and hand model, place-based learning

Transforming Eco-Paradigms for Sustainable Values

Ecological sustainability, as defined by the Brundtland Commission, means to meet the resource needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. The lack of sustainability values and the anthropogenic environmental paradigm of western culture are evidenced by the large ecological footprint of developed nations; therefore, education for sustainability is necessarily transformative. The goal of education for sustainability is to transform the environmental perspectives of the learners from viewing the environment as a commodity to a community, from consumer to conserver, from short-term reactor to long-term evaluator. Changing and expanding worldviews of learners is the goal of transformative learning (Mezirow, 1978; O’Sullivan, 2008; Taylor, 2007). Another perspective based on the work of Freire (2007/1970) emphasizes societal transformation. This social-emancipatory view of transformative learning fosters conscientization among participants through critical reflection for the purpose of creating a more equitable world (Freire, 1970). O’Sullivan presents a planetary view which defines transformative learning as a profound shift in awareness that alters one’s way of being in the world and one’s view of the interconnectedness of self, the human community and the natural environment (O’Sullivan, Morrel, & O’Connor, 2002; O’Sullivan, 2008). The theory of transformative learning has evolved over time, initially focusing on the individual but expanding to community and then a planetary view. From these perspectives, transformation goes beyond epistemological processes of a change of worldview to an ontological process of a change in being in the world (Lange, 2004).

Another, ancient tradition of transformative learning comes from an indigenous perspective. Indigenous education revolves around a transformational process of learning how to establish and maintain relationships between self, place and community or tribe (Cajete, 1994). Indigenous education is a life-long process of trial and tribulation that teaches an individual how to be in the world through reflection of personal or shared experience and participation in a greater community of life (Cajete, 1999). Indigenous epistemologies are grounded in the meaningful context of inter-relationships and nature experience. These ways of thinking are considered transformative because they reinforce the shaping factors of transformative learning which are critical reflection, emotional engagement and relational knowing (Taylor, 2007).

The indigenous perspective of transformative learning aligns with O’Sullivan’s (2008) planetary view of transformative learning and provides an important perspective of education for ecological sustainability (Cajete, 1999). The notion of reclaiming ancient wisdom traditions for ecological sustainability is prevalent in the literature. This approach to education also parallels the essence of place-based education which strives to reform and transform current stifling, heartless educational institutions to include the spirit of community, a re-imagined relationship to nature and a commitment to the responsibilities that grow from that relationship (Gilliam & Lane-Zucker, 1996). Critical transformative learning goes beyond the personal toward community action, even societal transformation. Approaching sustainability education through transformative experience could have pragmatic impact on the learner, the community and the environment.

Love of place and a sense of connection or belonging are foundational toward development of sustainability values. Critical ecological educators have claimed that love of place is the key to fostering sustainable behaviors (Meyers & Frantz, 2004). Leopold discusses love and respect when he describes his land ethic and land as a community to which we belong (Leopold, 1949). People care about and tend to who or what they love. Affect or emotions determine what we pay attention to, what we value, and how we make judgments and decisions. Emotions are the reasons for action and change because emotions are the context for interpreting and responding to experience. Research shows that active environmentalists attribute their commitment to the environment to love of a special place in nature as a child or adolescent, and sharing nature experiences with a beloved adult mentor (Carson, 1965; Chawla, 2006). This love of nature may need to be triggered by experience or will otherwise remain dormant. To inspire children to consider environmental behaviors and develop into adults that make ecologically sustainable decisions, it is important to provide opportunities for children to have prolonged experience in natural settings and to bond with a place rather than gloom and doom curricula about faraway places (Athman & Stanek, 2006: Semken & Freeman, 2008; Sobel, 1996). Love of nature or a special place could be critical in fueling the passion that motivates transformation of ecological paradigms.

Transformative Learning and Children

Transformative Learning Theory has been applied as an adult learning theory because it was assumed that children lack the experience, cognitive ability and critical reflection needed for transformative experience (Merriam, 2004; Taylor, 2007). However, research into how people learn has shown that children are quite capable of reflection and self-regulation of their learning; research has revealed a competence and metacognitive knowledge in young children (National Research Council, 2000). Because educators have commonly underestimated young children’s capacity for metacognition these abilities lay dormant and untapped in traditional classrooms (National Research Council, 2007). Metacognition, or thinking about thinking, involves self awareness of one’s abilities or limitations and self regulation of learning. Metacognition is essentially introspective and critically reflective. Dewey (1938/1997) claimed that reflection helps learners extract meaning through intellectual organization. With enriching experiences and opportunities to reflect, this ability can be nurtured to add meaning to school activity and sow the seeds for transformative experiences for young people.

It is believed that transformative learning requires independent, active learners while children are considered to be dependent, passive learners. Unfortunately, passive learning is fostered by the current educational system that does not utilize natural learning processes. The natural curiosity and active role of children as learners has been emphasized in various learning theories by Piaget, Vygotsky, Bruner and Dewey (National Research Council, 2000). In Taking Science to School (NRC, 2007) young learners are described as active exploratory learners and research is provided that supports that children’s thinking is surprisingly refined. Students who take responsibility and an active role in their learning are called self-regulatory learners and often possess an internal locus of control. Research in self-regulatory processes and internal locus of control has shown that these processes are teachable and can lead to increases in student motivation and achievement (Zimmerman, 2002; 2008). When people affect changes in their immediate environment, they affect changes within themselves; this can lead to greater self-efficacy and more responsible behavior in other areas as well (Rathzel & Uzzell, 2009).

Learning for children is not solely developmental in nature. There are transformational qualities involved in the maturation process that can be fostered and enhanced to make successful life transitions. Adult education is most often voluntary and tends to be authentic, more problem or project-based which gives the learning meaning and purpose. Children also need a spark of authenticity; for this engagement will lead to greater depth and meaning. The same factors that motivate adult learner engagement also motivate younger learners. Meaningful education focuses on transforming individuals regardless of age (Bracey, 2007). So it appears that transformational learning is a human process, not just an adult learning process. Looking toward the future of building just and sustainable societies, we need to include the next generation.

The Head, Heart and Hand Model

The construct of transformative experience that will be foundational to the model being presented is based on Dewey’s pragmatic aesthetics and application of learning to the everyday life and experience of the learner (Parrish, 2010, Puge & Girod, 2007, Wong, 2007). Learning has the potential to enrich and vitalize school experiences and provide aesthetic satisfaction that could lead to transformation of everyday experience (Puge & Girod, 2007). In Art as Experience, Dewey (1934) writes about the enriching possibility of an experience that can change a person’s relationship with the world, a new way of seeing, a new way of being in the world that is transformative.

Kevin Puge and his colleagues have published a series of inquiries on transformative experience in high school science students (Puge, 2002; Puge & Bergin, 2005; Puge & Girod, 2007; Puge, Linnenbrink-Garcia, Koskey, Stewart, & Manzey, 2010). Puge’s (2002) operational definition of transformative experience includes an expansion of perception, experiential value or interest and motivated use which is an active use of concepts learned during school in students’ personal lives. The idea of application of things learned in school to life outside of school relates to Puge’s definition of transformational learning (Puge & Girod, 2007). This construct of transformative experience is based on Dewey’s pragmatic aesthetics and application of learning to the everyday life and experience of the learner (Puge & Girod, 2007). Puge and Girod (2007) propose that science has the same potential as art to enrich and vitalize everyday experience and provide aesthetic satisfaction that could lead to transformation of our everyday experience. Unfortunately Puge’s work did not find large numbers of students having transformational learning experience in traditional science classrooms. A more engaging context such as a natural setting might be more effective in generating transformational experiences.

Sipos et al. (2008) explicitly link sustainability education with transformative learning through the organizing principle of head, hands and heart. The roots of this organizing principle can be found in Orr’s (1992) description of how to approach education for sustainability. He claims that such an approach not only integrates disciplines, but also intellect, emotion and body. Orr (1992) claims education should go beyond content or formal knowledge to include application and disposition of how to create meaning and value. In the Sipos et al. (2008) framework, head refers to engaging the cognitive domain through academic study, inquiry and understanding of ecological and sustainability concepts. Hands refer to the enactment of the psychomotor domain for learning practical skill development and physical work such as building, planting, painting etc. Heart refers to enablement of the affective domain in forming values and attitudes that are translated into behaviors (Sipos et al., 2008). Figure one shows the HHH model.

The Head, Heart and Hands Model for Transformative Learning

The blending of transformative learning and education for sustainability is a natural partnership because sustainability and transformative learning requires a change in perception, a change in values and active engagement. The model reflects that transformation is a multi-dimensional process and that changing sustainability values and environmental paradigms require more than a logical argument or an emotional appeal. Experience and reflection along with awareness and caring are needed to initiate a true transformational event. Reflecting can change perceptions and relation with a place changes one’s values about nature. Active engagement requires application of eco-friendly behaviors. Place offers a stimulating, authentic context for meaningful educational experiences that hold potential for personal growth for learners beyond academics.

Context of Place and Connectedness to Nature

Places are invested with meaning and shape our consciousness, social identities, attitudes and behavior (Hutchison, 2004). Place provides a context, an internal and external landscape, that frames, organizes and anchors experience which is needed to extract meaning and construct knowledge. Love of place inspires caring for place and connection to nature is associated with proactive environmental behaviors (Chawla, 2006; Meyer & Frantz, 2004). Education for sustainability, indigenous education and the planetary perspective of transformative education are related by a fundamental view of an intimate knowing of and belonging to place. Unfortunately, the majority of individuals in our society are urban dwellers who are alienated from the natural world, and therefore, have little direct connection to nature (Children and Nature Network, 2008; Louve, 2005; Orr, 1992; Pergams & Zaradic, 2008).

In addition to serving as an authentic context for transformative experiences that offers personally meaningful learning, there are many benefits to spending time in nature (Louv, 2005; Sobel, 1996). There is a large amount of evidence from studies in the area of biophilia supporting the notion that humans have a natural affinity to engage with nature and living organisms (Kahn, 1999; Kellert, 1997; 2002; Shepard, 1998). Literally, the term biophilia means love of life or living process. Nature experiences have been associated with cognitive, emotional, social and psycho-motor development as well as mental and physical health (Burdette & Whitaker, 2005; Frumkin, 2001; Kellert, 2002; Louv, 2005). Natural environments are an authentic context that many people find engaging and aesthetically inspiring (Braund & Reiss, 2006; Kellert, 1997; 2002). Learning in authentic or natural settings is a multi-sensory immersion, an immediate experience, that is compelling and often a novel experience. Natural environments not only draw students into deep and sustained engagement, nature also offers an enriching complex experience that benefits the well-being of people and even the well-being of the environment.

Through deep engagement, reflection and relational understandings, students find personal meaning and relevance in learning locally that adds purpose to their education. These value-laden educational experiences can be transformative by bringing a new perspective of relationship and responsibility to self and community with an improved attitude toward the personal growth that can result from learning (Tooth & Renshaw, 2009). Relationship with place inspires pro-environmental behaviors and sustainability values. If education began with efforts to learn about processes and places close to home, it could lead to a different understanding of ecological stewardship and sustainable community. Weaving curriculum into the community allows students to fully participate in their own world with head, heart and hands which is stimulating and engaging. Bringing the place into the curriculum puts real world learning into our schools and students’ lives and builds healthy connections among community members, young people and the environment. A key element of ecological awareness is an intimate relationship and sacred orientation to a place (Cajete, 1993). Connection and caring for natural places may be essential in developing sustainability values that underlie peoples’ environmental perspectives and behaviors (Kals, Schumacher, & Montada, 1999). Place also provides an experiential background for shared experience and reflection.

Reflection: Head

The function of reflection is to create meaning from experience by drawing connections and relations to previous experience, knowledge and ideas (Dewey, 1910; 1944, Kolb, 1984; Roberts, 2002). It is this connection to previous experience and knowledge that gives continuity and allows students to see the significance of their educational experience (Dewey, 1910; 1938). Research on how the brain learns has shown that comparing new experience to prior experience is the brain’s natural way of extracting meaning and integrating new knowledge with prior knowledge (Jensen, 2008; Ross & Olsen, 1993). Learning is not significant until it has undergone this critical process that allows the learner to incorporate the new learning into his or her behavioral repertoire (Wilson & Burket, 1989). Although both Dewey (1910) and Kolb (1984) argue that experience is the basis for learning, they also both claim that learning cannot take place without reflection (ERIC, 1992). Reflection is also an essential element of transformational experiences (Mezirow, 1978; Taylor, 2007). Critical reflection can lead to self-awareness which is necessary for change because without reflection one cannot: identify, question and reframe underlying values and beliefs; acknowledge and challenge assumptions; recognize bias and identify fears; understand strengths and weaknesses (ERIC, 1992). This inward contemplation is a part of identity formation and underlies the values and beliefs that support the views individuals hold and the behaviors they express (Cornu, 2009).

Reflection is often cited as an essential element of metacognitive and student-centered, constructivist learning practices, but is often the most neglected element when implementing these practices (Baviskar, Hartle & Whitney, 2009). There are many barriers to reflection in most classroom settings. Providing time necessary for reflection is difficult because most state curricula are a mile wide and an inch deep, which leaves little space for deep, meaningful learning (AAAS, 1990). Some practitioners may not see the value of reflection if they themselves are not reflective and some may assume that students are reflecting on their own. In addition, most teachers are not trained to prepare or guide students for reflective practices. Experiential programs in outdoor education, adventure education, restoration education and place-based education programs consider group and individual reflection of participants an essential component of the experiential learning cycle.

Reflection often occurs through interaction with others; learners process experience with place through expression to others with shared experience (Dewey, 1944; Roberts, 2002). The places we encounter and the people we share experience and thoughts with are mirrors and sounding boards for our own reflection. Re-evaluating our beliefs and values stems from critical reflections which are constructed by our place in the world and the relationships we build with others.

Relational Knowing: Heart

The Lakota people have a saying often used in ceremony, mitakuye oyasin, which means to all my relations and recognizes all living organisms as relatives. In this worldview, people are connected to all aspects of the natural world and related to all living creatures. Most native people’s worldview holds the core perception that we are connected to all life which builds a strong sense of relationship with place and all who live there (Spretnak, 1991). All people are part of social and biological systems whose lives are framed by relationships and interactions within these systems (Riley-Taylor, 2002). Our survival and quality of life are dependent upon relations with healthy environments, communities and personal bonds. The gateway to perception is a relation, an interconnection, between our senses and the world beyond (Blenkinsop, 2005).

Relational knowing can be defined as awareness of the relationships shared with community and the natural world, which seeks to overcome the dualistic separation underlying Western culture (Riley-Taylor, 2004). Alternative ways of knowing are often overlooked within Western societies which value reductionist, rational ways of knowing. From an indigenous perspective, Cajete (1999) recognizes four categories of ways of knowing: thinking, feeling, intuition and sensation. Gardner’s (1999) intelligences are examples of other ways of knowing. There are many ways to be smart yet there is a rank value attributed to them. The rational forms of intelligence, logical and linguistic, are valued over other ways of knowing such as emotional intelligence or intuition. Dualistic conceptions of existence that separate mind and body can be traced to Aristotle and more recently, Descartes, and have profoundly affected Western thought (Gutek, 2009). This dualistic separation of the human mind and the sensory world allows people to rationalize the objectification and alienation of what is perceived as not rational. This includes the sensory world of nature, women, and indigenous people (Martusewicz, 2005). In other words, the same frame of cultural values that allow for destruction and domination of the land and wildlife allow for the devaluing of women and people from different cultures, especially cultures that are considered to be primitive, uncivilized, less sophisticated or less rational by Western measures (Nabhan & Trimble, 1994). It is easier exploit a commodity than a community and to exclude the other from ethical codes attributed and granted exclusively to civilized people. This dualistic way or thinking sets humans against the larger community of life and relational knowing (Riley-Taylor, 2003).

Relationship has a powerful affect on people’s emotions, thoughts and behaviors because human beings have a fundamental need to belong (Baumeister & Leary, 1995). It is community relationships that transform pointless lives into directed, meaningful experiences (Shapiro, 2006). In Losing Heart: The Moral and Spiritual Miseducation of America’s Children, Shapiro (2006) claims that community provides: the means through which we receive recognition and affirmation of our value; nurturing, caring and compassion; connection to purpose and meaningful lives. Through service and common goals, individuals bind together and receive relational support (Blenkinsop, 2005).

Because self-awareness and identity formation occurs through continuing relationship, knowledge of self becomes distinguished as we embrace diversity, yet social and economic privilege often leads to exclusionary practices (Blenkinsop, 2005; Martusewicz, 2005). Globalization has contributed to creation of a monoculture. In the same way that human activity alters biologically diverse land communities into monocultures, lack of deep community ties atomizes people into social monocultures. There is little connection to the life systems that sustain us. People have important relations with stuff and attach identity to the value of material accumulations rather than the quality of relationships with other people and with place.

Love is associated with the affective domain. A significant emotional event is often the impetus to change, to transform. Connection of emotion to self-knowledge is an empowering resource for willingness and acceptance of the need for critical reflection and changing behaviors (Zembylas, 2003). Critical reflection, essential for transformative learning experiences, is a cognitive process, but what motivates a person to look within? One needs to be emotionally invested to engage in self-examination and transformation. Love of place fuels this emotional investment.

Deep Engagement: Hands

From Puge’s (2002) construct of transformative learning experience, active use of concepts learned refers to a learner incorporating educational experiences into their everyday life. From a sustainability education point of view, this would result in an outcome of sustainability practices as a part of daily life. Being physically present in a place, building relationship with that place, critically reflecting on the values one puts on a place can transform perspectives, change behaviors and increase engagement in sustainable community practices. Holistic involvement, body, mind, heart and place is deeply moving and deeply engaging.

To be engaged is to actively participate, to be involved and invested. Engaged learners exhibit characteristics of being attracted to their task, persistence in their task despite obstacles or challenges and take visible joy in accomplishing their task (Schlechty, 1994). As a meta-construct, engagement is conceived as an interaction between context and individual need for autonomy, relatedness, complexity and challenge balanced by competence (Fredricks, Blumenfeld, & Paris, 2004). Educational research on engagement is framed in terms of categories, measures, precursors and outcomes in a 2004 meta-analysis by Fredricks, Blumenfeld and Paris. Research tends to be divided into three areas: behavioral, cognitive and affective. The area of behavior includes conduct, on-task behaviors, participation in extracurricular activities and attendance. Diminishing engagement is included in this area and often examines dropping out. Generally, behavior approaches focus on external efforts of students. Investigations in the cognitive area focuses on motivation self-regulated learning, self-efficacy, meta-cognition and intellectual endeavors. These investigations examine internal efforts and personal qualities of students. In the area of affect, investigators look at attitudes, interests, belonging and relationships. (Fredricks, et al., 2004).

Strong, Silver and Robinson (1995) identified four goals and related needs that motivate engagement which are: success and need for mastery; curiosity and need for understanding; originality and need for self expression; relationship and need for involvement with others. Success affects a learner’s academic self-efficacy, a learners beliefs in their abilities, which influences their cognitive engagement with a learning task (National Research Council, 2007). Curiosity in a topic is related to the value and relevance of that topic personally to the learner (Strong et al., 1995). Originality and self expression are associated with autonomy and choice. People have an inner drive toward interpersonal involvement so relationships and belonging are motivating to individuals (Strong et al., 1995).

Other factors that affect engagement are related to complex, enriching learning environments. Influences outside the realm of school such as family, culture and community affect engagement. But educational context, along with teacher and peer support, also have a great influence on engagement. Ross and Olsen (1993) define an enriching environment as a stimulating setting which is alive with resources and reflective of real life. In terms of educational context, a strong and unique predictor of engagement is challenging tasks in authentic environments (Fredrick et al. 2004). In How People Learn, Bransford (2000) states that learners are more motivated and engaged when they can use what they have learned to do something that has an impact on others-especially their local community. So, we come full circle back to the notion of place as meaningful context for engagement. The simplified illustration of the head, hand and heart model does not show the myriad of relationships that place has with how an individual thinks, feels and engages with the world.

Weaving it All Together

Ecology is a multi-disciplinary study that includes all branches of science: biology, geology, chemistry, meteorology, hydrology, forestry, agriculture, soil science, etc. The interaction of people with ecology adds subjects such as psychology, anthropology, philosophy, economics, politics, etc. Blending it all together is a daunting task especially in the environment of specialization that permeates academia. A holistic framework from the personal perspective of head, heart and hands is a starting point to model changes in the approach to ecological sustainability and educational reform that offers meaning and purpose to the learner. Sustainability requires localizing by learning about the places in which we live. Because we are so far removed from life-sustaining systems, we give them little thought. If people were, not just aware, but experienced in their local bioregion, they could directly learn how ecosystems support life (Pyle, 2008). Caring attitudes expand values and the willingness to make lifestyle changes that contribute to sustainable communities. Love of place underlies the motivation to change behaviors. Local environments can serve as a resource or laboratory to investigate water issues, food production, energy, nutrient cycles, and waste flows, which will lead to eco-literate citizens who reflect upon their impact on their environment and value the reduction of their ecological footprint (Orr, 1992; Theobald, 2000).

The Head, Heart and Hands model of Transformative Learning could be an organizing principle to integrate and transform pedagogical perspectives for sustainability education (Sipos, et al., 2008). This holistic synthesis could serve as a framework for evaluation of innovative environmental education programs, evaluation of program influence on students’ green behaviors and changes in environmental worldviews and values. The essential elements of transformation– deep engagement, relational knowing and reflection can have a greater impact within an authentic context for meaning-making. Pugh’s (2002) construct offers an analytic tool for measuring transformational experiences through expanded perception, expanded value and proactive use of environmental concepts. Being able, to some extent, to quantify a qualitative experience is invaluable to researchers. Puge’s (2002) construct synthesizes nicely with head, heart and hands concept that Sipos et al. (2008) associates with sustainability education.

Relevant educational experiences are needed to reshape teaching and learning for more productive means (Sipos et al., 2008). The holistic pedagogy of engaging head, hands and heart reclaims a personal perspective which brings community into the curriculum and the real world into our schools and student’s lives. Studies have shown that students are not actively engaged in their schooling experience (Puge & Bergin, 2005), but love, purpose and authenticity can be infused into the curriculum through the context of place. Through deep engagement, reflection and relational understandings, students find personal meaning and relevance in learning locally. Bridging the gap between school, community and environment, between living and learning, allows students to develop and apply knowledge and skills in the immediate context of real life just as our ancestors did and indigenous people continue to do today. Place not only adds active engagement and a spark of inspiration to a child’s learning experience, it also encourages a pragmatic knowledge of local bioregions. Without expanded perspective of self and environment, expanded value of relational knowing, and changes in environmental behaviors, sustainability will not be obtainable. Sustainable communities will not be built through legislation or technological innovations, they will be created by committed people who are informed, who care and who take action. The framework of head, heart and hands illustrates people progressing from knowing to caring to loving to doing.

Environmental education research focuses on environmental behaviors, environmental awareness and advocacy but less on the holistic growth and development of the learner in other areas. Outdoor educators know that something intangible happens to people in natural landscapes. Because of the challenge of natural environments and authentic learning activities, individuals become more self-reliant, responsible and reflective (D’amoto & Kransy, 2005; Sheard & Golby, 2006). They change and are transformed, but this qualitative phenomenon is difficult to measure and explain. Perhaps love is the intangible piece that is challenging to researchers. Pugh’s (2002) operational definition of transformative learning experience is a new lens from which to examine outdoor environmental education experiences and place-based community projects. As our country faces rising dropout rates and low international academic ratings, the federal government is seeking innovative programs that can show positive outcomes. If something as simple as taking students outdoors and involving them in their own community can get them excited enough to personally engage themselves in sustainable behaviors, then it is worth investment.

References

American Association for the Advancement of Science (1990). Science for all Americans. New York: University of Oxford Press.

Athman Ernst, J., & Stanek, D. (2006). The prairie science class: A model of re-visioning environmental education with the National Wildlife Refuge System. Human Dimensions of Wildlife, 11, 255-265.

Baviskar, S. N., Hartle, R. T., & Whitney, T. (2009). Essential criteria to characterize constructivist teaching: Derived from a review of the literature and applied to five constructivist-teaching method articles. International Journal of Science Education, 4(1), 541-550.

Blenkinsop, S. (2005). Martin Buber: Educating for relationship. Ethics, Place & Environment 8(3), 285-307.

Bracey, G. W. (2007). How does school influence out-of-school experience? Principal Leadership, 8(4), 54-56.

Braund, M., & Reiss, M. (2006). Towards a more authentic science curriculum: The contribution of out-of-school learning. International Journal of Science Education, 28(12), 1327-1388.

Burdette, H. L., & Whitaker, R. C. (2005). Restructuring free play in young children: Looking beyond fitness and fatness to attention, affiliation, and affect. Archive of Pediatric Adolescent Medicine, 159, 46-50.

Cajete, G. (1993). An enchanted land: Spiritual ecology and theology of place. Winds of Change, 8(2), 50-53.

Cajete, G. (1994). Look to the mountain: An ecology of indigenous education. Skyland, NC: Kivaki Press.

Cajete, G. (1999). The making of an indigenous teacher: Insights into the ecology of teaching. In J. Kane (Ed.), Education, Information, and Transformation Essays on Learning and Thinking. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, Inc.

Carson, R. (1965). A sense of wonder. New York: Harper Collins

Chawla, L. (2006). Learning to love the natural world enough to protect it. Barn nr. 2, p.57-78. Retrieved on July 25, 2009 from: http://www.childrenandnature.org/downloads/Chawla_LearningtoLove.pdf

Children and Nature Network (2008). Children and nature 2008: A report on the movement to reconnect children to the natural world. Cheryl Charles, Richard Louv, Lee Bodner, & Bill Guns (Eds). Retrieved January, 2009 from: http://www.childrenandnature.org/

Cornu, A. L., (2009). Meaning, internalization, and externalization: Toward a fuller understanding of the process of reflection and its role in the construction of the self. Adult Education Quaterly, 59(4), 279-297.

D’amoto, L. G., & Kransy, M. E. (In review, Journal of Experiential Education). Outdoor adventure education: Applying transformative learning theory in addressing instrumental and emancipatory EE goals. Retrieved December 19, 2009 from: http://krasny.dnr.cornell.edu/documents/damato_krasny_outdoor_JEE.pdf

Dewey, J. (1910/2005). How we think. New York: Barnes & Noble, Inc.

Dewey, J. (1934). Art as experience. New York: Penguin Group.

Dewey, J. (1938/1963). Experience and education. New York: Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Dewey, J. (1944). Democracy and education. New York: Simon & Schuster, Inc.

ERIC Development Team, (1992) ED346319 1992-00-00 Reflective practice in adult education. ERIC digest No.122. Retrieved May 19, 2010 from www.eric.ed.gov

Fredricks, J. A., Blumenfeld, P. C., & Paris, A. H. (2004). School engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Review of Educational Research,74, 59-109.

Freire, P. (1970/2007). Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York: The Continuum International Publishing Group Inc.

Frumkin, H. (2001). Beyond toxicity: Human health and the natural environment. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 20(3), 234-240.

Gardner, H. (1999) Are there additional intelligences? The case for naturalist, spiritual, and existential intelligence. In J. Kane (Ed.), Education, Information, and Transformation Essays on Learning and Thinking. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, Inc.

Gilliam, M. G. H., & Lane-Zucker, L. J. (1996). Introduction in David Sobel’s Beyond Ecophobia: Reclaiming the heart in nature education. Great Barrington, MA: The Orion Society.

Gutek, G. L. (2009) New Perspectives on Philosophy and Education. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

Hutchison, D. (2004). A natural history of place in education. New York: Teachers College Press.

Kahn, P. H. (1999). The human relationship with nature: Development and culture. Cambridge,MA: The MIT Press.

Kals, E., Schumacher, D., & Montada, L. (1999). Emotional affinity toward nature as a motivational basis to protect nature. Environment and Behavior,31(2), 178-202.

Kellert, S. R. (1997). Kinship to mastery: Biophilia in human evolution and development. Washington, DC: Island Press.

Kellert, S. R. (2002). Experiencing Nature: Affective, cognitive, and evaluative development in children. In Peter H. Kahn, Jr., and Stephen R. Kellert (Eds.), Children and nature: Psychological, sociocultural an evolutionary investigations. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Kolb D. (1984). Experiential learning: experience as the source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

Lange, E. A. (2004). Transformative and restorative learning: A vital dialectic for sustainable societies. Adult Education Quarterly, 54(2), 121-139.

Leopold, A. (1949). A sand county almanac and sketches here and there. New York: Oxford University Press.

Louv, R. (2005). Last child in the woods. Chapel Hill, NC: Algonquin Books.

Martusewicz, R. (2005). Eros in the commons: Education for eco-ethical consciousness in a poetics of place. Ethics, Place & Environment, 8(3), 331-348.

Mayer, F. S., & Frantz, C. M. (2004). The connectedness to nature scale: A measure of individuals’ feeling in community with nature. Journal of Environmental Psychology 24, 503-515.

Merriam, S. B. (2004). The role of cognitive development in Mezirow’s transformative learning theory. Adult Learning Quaterly, 55, 60-68.

Mezirow, J. (1978). Perspective transformation. Adult Education 28, 100–110.

Nabhan, G. P., & Trimble, S. (1994). The geography of childhood: Why children need wild places. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

National Research Council, (2000). How people learn: Brain mind, experience, and school. Washington: National Academy Press.

National Research Council (2007). Taking science to school: Learning and teaching science in grades K-8. Committee on Science Learning, Kindergarten Through Eighth Grade. Richard Duschl, Heidi A Schweingruber, and Andrew Shouse, Editors. Board on Science Education, Center for Education. Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. Washington, DC: The National Academy Press.

Orr, D. (1992). Ecological literacy: Education for a post modern world. Albany, NY: State University of New York.

O’Sullivan, E. (2008). Finding our way in the great work. Journal of Transformative Education,6, 27-32.

O’Sullivan, E., Morrel, A., & O’Connor, M. A. (2002). Expanding the boundaries of transformative learning: essays on theory and praxis. New York: Palgrave.

Parrish, P. E. (2009). Aesthetic principles for instructional design. Educational Technology Research Development, 57, 511-528. doi 10.1007/s11423-007-9060-7

Pergams, O.R. W., & Zaradic, P. A. (2008). Evidence for a fundamental and pervasive shift away from nature-based recreation. Retrieved October 26, 2008 from http://www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.0709893105

Pugh, K. J. (2002). Teaching for transformative experience in science: An investigation of the effectiveness of two instructional elements. Teachers College Record, 104(6), 1101-1137.

Pugh, K. J., & Bergin, D. A. (2005). The effect of schooling on students’ out-of-school experience. Educational Researcher,34(9), 15-23.

Pugh, K. J., & Girod, M. (2007). Science, art, and experience: Constructing a science pedagogy from Dewey’s aesthetics. Journal of Science Teacher Education,18(9), 9-27.

Puge, K. J., Linnenbrink-Garcia, L., Koskey, K. L. K., Stewart, V. C., & Manzey (2010). Motivation, learning, and transformative experience: A study of deep engagement in science. Science Education, 94, 1-28.

Pyle, R. M. (2008). No child left inside: Nature study as a radical act. In D. A. Gruenewald & G. A. Smith (Ed.), Place-Based Education in the Global Age. NY: Taylor and Francis Group, LLC.

Rathezel, N., & Uzzell, D. (2009). Transformative environmental education: A collective rehearsal for reality. Environmental Education Research,15(3), 263-277.

Rickinson, M., Dillon, J., Teamy, K., Morris, M., Choi, M. Y., Sanders, D., & Benefield, P. (2004). A review of research on outdoor learning. National Foundation for Educational Research, King’s College London.Retrieved November 20, 2010 from: http://www.field-studies-council.org/documents/general/NFER/A_review_of_research_on_outdoor_learning.pdf

Riley-Taylor, E. (2002). Ecology, spirituality, and education: Curriculum for relational knowing. New York, NY: Peter Lang Publishing, Inc.

Riley-Taylor, E. (2003). Relational knowing: An ecological perspective on curriculum. Journal of Curriculum Theorizing, 19(3), 39-49.

Riley-Taylor, E. (2004). Culture and ecology: Toward living a more balanced commitment. The International Journal of Humanities and Peace, 20, 59-62.

Roberts, J. W. (2002) Beyond learning by doing: The brain compatible approach. Journal of Experiential Education, 25(2), 281-285.

Ross, A., & Olsen K. (1993). The way we were…the way we can be: A vision for the middle school through integrated thematic instruction. Village of Oak Creek, AR: Susan Kovalik & Associates.

Schlechty, P. (1994) Increasing Student Engagement, Missouri Leadership Academy.

Semken, S., & Butler Freeman, C. (2008). Sense of place in the practice and assessment of place-based science teaching. Science Education, 92(6), 1042-1057.

Shapiro, H. S. (2006). Losing heart: The moral and spiritual miseducation of America’s youth. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc., Publishers.

Sheard, M., & Golby, J. (2006). The efficacy of an outdoor adventure education curriculum on selected aspects of positive psychological development. Journal of Experiential Education, 29(2), 187-209.

Shepard, P. (1998) Coming home to the Pleistocene. Washington, DC: Island Press.

Sipos, Y., Battisti, B., & Grimm, K. (2008). Achieving transformative sustainability learning: Engaging head, hands and heart. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 9, 68-86.

Sobel. D. (1996). Beyond ecophobia: Reclaiming the heart in nature education. Great Barrington, MA: Orion Society.

Spretnak, C. (1991). States of grace: The recovery of meaning in the postmodern age. NY: HarperCollins Publishers.

Strong, R., Silver, H.F., & Robinson, A. (1995). What do students want? Educational Leadership, 53(1), 8-12.

Taylor, E. W. (2007). An update of transformational learning theory: A critical review of the empirical research (1999-2009). International Journal of Lifelong Education, 26(2), 173-191.

Theobald, P. (2000). Communities as curricula. Forum for Applied Research and Public Policy. 15, 106-11.

Tooth, R., & Renshaw, P. (2009). Reflections on pedagogy and place: A journey into learning for sustainability through environmental narrative and deep attentive reflection. Australian Journal of Environmental Education, 24, 95-104.

Wong, D. (2007). Beyond control and rationality: Dewey, aesthetics, motivation, and educative experiences. Teachers College Record, 109, 192-220.

Zembylas, M. (2003). Emotions and teacher identity: A poststructural perspective. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 9(3), 213-238.

Zimmerman, B. J. (2002). Becoming a self-regulated learner: An overview. Theory into Practice, 41(2), 64-70.

Zimmerman, B. J. (2008). Investigating self-regulation and motivation: Historical background, methodological developments, and future prospects. American Education Research Journal, 45, 166-183.

Julie Singleton is an assistant professor in Texas A&M’s College of Education. She teaches science methods and other curriculum and instruction courses. Her research interests are environmental literacy, connectedness to nature, land ethics and transformative learning.

Julie Singleton is an assistant professor in Texas A&M’s College of Education. She teaches science methods and other curriculum and instruction courses. Her research interests are environmental literacy, connectedness to nature, land ethics and transformative learning.

a great suggested reading., I read the same topic of Rudolf Steiner, JH Pestalossi and KH Dewantara., I found 8H model of NG Ghoucian. Thanks for your article.

Best regards