Some effects of an unstructured outdoor activity on preschoolers: A case study from Aotearoa, New Zealand

Link to the JSE General Issue May 2022 Table of Contents

Article PDF

Abstract: Early childhood educators emphasize that outdoor education learning outcomes are very important for preschoolers because early childhood education has a huge effect on the later stage of adulthood. Outdoor education can take place on playgrounds or in natural environments. The aim of this study was to determine some effects of an unstructured outdoor activity on preschoolers. A qualitative case study methodology was used in order to assess the effect of a bush explorer activity on children. In terms of establishing the research’s reliability, the qualitative analyses were supported by the triangulation data collection methods, which included non-participant observation and parents’ interviews. Content analysis was used in order to evaluate the data. According to the results, eleven different themes were determined: Problem solving, self-confidence, environmental awareness, observing and exploring, friendship and social skills, creativity, sharing experience, relaxing, having fun, conflict, and rejection. All themes, except conflict and rejection, are coherent with the literature.

Keywords: preschoolers, outdoor education, unstructured play, early childhood education, case study, qualitative methodology, New Zealand

Introduction

Outdoor education has different definitions and is used interchangeably with different concepts such as adventure education, natural education, museum education, lifelong learning, recreation education or experiential education (Okur, 2012; Okur-Berberoglu, 2017a). Outdoor education is defined as another dimension of learning and complementary to formal classroom education (Brodin & Lindstrand, 2006). Brodin and Lindstrand (2006:17) explain that outdoor education

“… can be used to describe activities going on outdoors and our philosophy of learning is that learning takes place in all situations and contexts where a human being is involved. This means that there are no situations in real life where learning does not take place.”

Brodin and Lindstrand (2006:17) say that the definition of outdoor education may change according to research’s context, aim and how a researcher conducts the study. The contexts coming up from outdoor education are classified under six titles: Learning and education, Wilderness and nature, Psycho-experimental activities, Psycho-social aspects of outdoor education, Facilitation in different outdoor contexts, and Multi-dimensional aspects of outdoor education (Brodin & Lindstrand, 2006: 18). These kinds of different outputs can be related to philosophical roots of outdoor education.

Theoretical Framework

The roots of outdoor education philosophy are based on Comanius, Rousseau, Pestalozzi and Dewey (Okur, 2012; Okur-Berberoglu, Guder, Sezer & Yalcin-Ozdilek, 2013; Okur-Berberoglu, 2017b). It is thought that Rachel Carson might also be added to this list. Comenius in the 17th century stresses that a child before starting school should interact with a rock, flower or an animal in order to understand a subject (Hammerman & Hammerman, 1964). According to Rousseau (1979), children can learn best from their direct experiences from the immediate environment and learning primarily comes from nature, people in the environment and from objects around the child. Rousseau (1979) also states that our first teachers are five senses because we can perceive and experience the environment by our five senses. These experiences create better learning because they help us to transfer our knowledge and acquisitions to long-term memory rather than forgetting quickly (Brodin & Lindstrand, 2006; Kraft & Kielsmeier, 1995; Okur-Berberoglu, 2015a) Pestalozzi highlights that first-hand experiences are important for children (Okur, 2012; Okur- Berberoglu et al, 2013). Adults should not answer children’s questions directly; they moderate children’s experience and discovery (Rousseau, 1979) . Children, therefore, are able to develop heuristic learning. (Siraj-Blatchford & Macleod-Brudenell, 1999; Stine 1997). Carson (1956) also emphasizes that learning happens when children use five senses and the five senses open their disused sensory channels. According to Carson (1956) and Louv (2005), people have lost their learning ability by using five senses because of technology and an industrial living style. All these ideas are combined with Kolb’s Experiential Learning Theory. Kolb (1984) defines experiential learning as a transformation process of knowledge in the mind which happens by different first-hand and hands-on experiences. Kolb’s perspective mostly reflects the cognitive side of outdoor education (Okur-Berberoglu, 2014; Yalcin & Okur, 2014) . However, there are different kinds of outputs for outdoor education.

In terms of an educational perspective, Waite (2009:1) classifies the aims of outdoor education under three categories: physical wellbeing, social and emotional wellbeing, and different kinds of learning. Cooper (2015) evaluates outdoor education regulation in the USA in her article and arrays benefits of natural outdoor learning environment as improves self-regulation, advances physical fitness and gross motor development, improves nutrition, improves eyesight, Promotes cognitive development, improves academic performance, lessens the symptoms of ADHD and improves concentration, promotes self-confidence, builds understanding and appreciation of ecosystems, food systems, and environmental processes (Cooper, 2015:2).

Table 1. The Comparison of the Context, Benefits and Aims of Outdoor Education with the Research Results

As can be seen at Table 1, the context, benefits and aims of outdoor education are very coherent to each other in terms of cognitive, affective and kinesthetic learning areas. In terms of child development, early childhood educators and researchers point out that these outdoor education outputs are very important for preschoolers because early childhood education (ECE) has huge effect on the later stage of adulthood (Brodin& Lindstrand, 2006) especially in terms of creativity (Louv, 2005).

Literature Review of Pre-schoolers and Outdoor Learning

Children should experience outdoor activities and education in their early years because these activities and education might help children to awe, wonder and enjoy (Carson, 1956; Rousseau, 1979; Wilson, 1996). There is no need to teach something directly to a child (Carson, 1956). It is enough to let children be exposed to the outdoors’ magic environment according to Carson (1956). When children observe and explore something outdoors, they will have a sentimental connection with things at the first stage; later they would like to learn about what they sense on their own (Carson, 1956; Rousseau, 1979). Wilson (1996) also draws attention that there should not be a strict education programme for children because they cannot concentrate on something very long. Children, therefore, should be encouraged to discover whatever they find interesting. Teachers should be a facilitator and present some tools to children to discover them in the natural environment (Rousseau, 1979). Notwithstanding, each country has different ECE curriculum, regulations, and implications. For example, there is no mandatory regulation in the USA. However, it is suggested that children should have 30 minutes outdoor play every three hours and each child should have at least 75 square metres at the early childhood centre (Cooper, 2015). Wagner (2000) mentions in her article how school grounds should be designed for outdoor education of K-5 and K-12 students in the USA. Outdoor education programmes might be carried out on the school grounds as well as the outside world.

Waite (2009) tries to determine outdoor learning opportunities of 2-11 years-old children in the UK. She collected her data by a survey and some educators said that they were not able to use the outdoor environment because of health and safety issues. According to her results, outdoor learning experiences of preschoolers in the UK appears to be on the decline. However, child-minders support outdoor learning environments and think that outdoors give preschoolers more discovery opportunities. One of the educators says “Learning outdoors can add awe and wonder to knowledge and experience.” (Waite, 2009:8). The UK government and institutions support outdoor learning settings; however, teachers and educators do not know how to use outdoors properly, according to Waite’s study (2009). Therefore the Qualifications and Curriculum Authority started working on a guide for teachers and educators (Waite, 2009). The other important issue is a gap between educational aims and measurement of outdoor learning (Waite, 2009). Waite (2009) emphasizes that the UK government should prepare a guide according to age levels to show how to use the outdoors and how to measure outdoor learning.

Friedrich Wilhelm Fröbel, who is the creator of kindergartens, points out that children should play whatever they want, and these activities should be free from adult influence. Outdoors give children a rich learning environment and to test their boundaries. (Fröbel, 1895) According to Brodin and Lindstrand (2006)’s report, outdoor activities are not evaluated as a learning environment despite the fact that outdoor learning is mentioned in Sweden’s ECE curriculum. There are some studies related to outdoor education however studies that aim at preschoolers and outdoor education are very limited. This means preschooler and outdoor education combination is overlooked by researchers and educators. Outdoor education is mainly used at forest preschools in Sweden. However, these preschools have been criticised in terms of saving money on children because they exclude the regular school premises from the budget. Karin Engdahl (2005 in Brodin & Lindstrand, 2006) suggests conducting further studies in order to understand what preschoolers learn from outdoor play. (Brodin & Lindstrand, 2006)

Most studies related to preschoolers are based on the connection with the natural environment and favourable effects of outdoors on the environmental insight and science education of children (Conezio & French, 2002; Louv, 2005; McClain & Vandermaas-Peeler, 2016; Vandermaas-Peeler & McClain, 2015). Louv (2005) mentions many positive outputs of the outdoors for American students in his book. One of these outputs is creativity especially for preschoolers but this inference for preschoolers are mostly based on his observations. However, he says it is not known yet what the influence of unstructured natural landscape and experiences in nature on human development and health (Louv, 2005: 46). Louv (2005: 306) says we need controlled experimental studies in order to understand child-nature relation. Louv’s outdoor inference for preschoolers might be summarised as:

Unstructured nature + unstructured play-> having fun + self-confidence + creativity (exploring/ observing) + awareness + emotional connection to the land + learning

Some of the studies aim to determine outdoor and indoor physical activity levels of preschoolers in Sweden and the USA, especially in terms of health issues such as obesity (Raustrop et al, 2012). They find outdoor activity levels are higher than indoor activity levels and the researchers suggest that educators should encourage preschoolers for outdoor activities. There are different kinds of outdoor studies based on preschoolers in Sweden (Brodin& Lindstrand, 2005; Engdahl, 2005; Lindstrand, 2005), Australia (Cullen, 1988) and Turkey (Yıldırım & Akamca, 2017). They find that outdoor activities stimulate preschoolers’ gross-motor, social, dramatic and constructive play developments and preschoolers might learn the names of new objects which they encountered for the first time. However, these studies were conducted on preschools’ yards or playgrounds (Brodin& Lindstrand, 2005; Cullen, 1988; Engdahl, 2005; Lindstrand, 2005) or the teachers carried on a structured education programme for preschoolers (Yıldırım & Akamca, 2017).

Literature Review of New Zealand (NZ)

Outdoor education is an important part of preschoolers in NZ (McLachlan, 2013; Ministry of Health, 2017; Stephensen, 1999;). Some of the studies related to preschoolers and outdoors are based on determination of physical activity levels of children (Ku, 2011; Oliver et al, 2007; Oliver, 2008; Young, 2017). These studies are closely connected with health issues such as obesity (Gerritsen, 2016; Young, 2017), cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, bone health (Ku, 2011; Ministry of Health, 2017; Oliver et al, 2007; Oliver, 2008) or sun protection (Duignan et al, 2014). These studies also suggest that ECE education centres should present more outdoor times and activities for preschoolers (Ali et al, 2017; Gerritsen, 2016; Ku, 2011; Ministry of Health, 2017; Oliver et al, 2007; Oliver, 2008; Young, 2017) but they should also consider protection from sunlight while having outdoor activities (Duignan et al, 2014). Stephenson (1999) observes forty-five children in indoor and outdoor environments of a childcare centre. She finds physical and cognitive positive outputs for outdoor activities. However, all those researches above are based on the playgrounds or gardens of the centres or kindergartens.

Burke (2008), emphasises the multicultural population of NZ and compares NZ- Japan ECE centres in terms of pedagogical differences. Holdom (2018) and O’Brien (2015) evaluated Te Whāriki ECE programme of NZ in terms of science-mathematics-technology education while Kumar and Whyte (2018) evaluate Te Whāriki science education in terms of sociocultural environment. These researchers suggest using outdoors for hand-on experiences however their studies are at the theoretical level. Okur-Berberoglu (2021a) observes a preschooler in outdoor environments for two years and finds observing, exploring, cognitive development, creativity, and self confidence themes. Only Okur-Berberoglu’s study is based on unstructured outdoor plays in NZ and she suggests research designs with control groups to test her research’s results.

Louv (2005) mentions many positive outputs of outdoors for students in his book and asks, “What do we know about the influence of unstructured natural landscape and experiences in nature on human development and health?” (Louv, 2005: 46). Karin Engdahl (2005 in Brodin& Lindstrand, 2006) also suggests conducting further studies in order to understand what preschoolers learn from outdoor play.

This study tries to answer Richard Louv’s and Karin Engdahl’s suggestions and aims to determine some outputs of an outdoor activity which is named ‘Bush Explorer’. The research is unique in terms of some points:

1. The target group of the study is preschoolers who are around 3.5-4 years old.

2. The bush explorer activity is an unstructured outdoor activity.

3. The children in the bush have unstructured play.

The limitation of this study is there is no control group.

Methodology

The case study based on qualitative methodology was used in order to assess the effect of the bush explorer activity on children. The preference for the case study format was due to its usefulness in terms of collecting enough data (Yildirim & Simsek, 2006), and the fact of its capacity for yielding descriptive and explanatory results (Forces & Richer, 1973 in Zanovello, 1999; Okur-Berberoglu, 2015b). In terms of establishing the research’s reliability, the qualitative analyses were supported by the triangulation data collection method, which included: non-participant observation and parents’ interviews (Bas & Akturan, 2008; Yildirim & Simsek, 2006; Zanovello, 1999).

NZ’ s ECE programme (Te Whāriki)

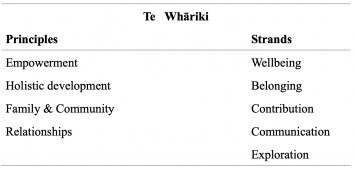

New Zealand’s ECE curriculum is named as ‘Te Whāriki’. This curriculum is defined as ‘mat for all to stand on’ (Te Whāriki, 2017:10) and based on Māori philosophy (Hemara, 2000). It has four principles and five strands. Principles are empowerment, holistic development, family and community and relationships. Strands are well-being, belonging, contribution, communication and exploration (Table 2). These principles and strands have interwoven relationship to protect children’s right, health and wellbeing, and cultural identity (Hemara, 2000; Te Whāriki, 2017)

Children are seen as confident and competent learners from birth according to Te Whāriki and can learn by meaningful interactions with people and places. This learning process goes on throughout children’s lives. (Hemara, 2000) However, there is no proper activity definition in Te Whāriki.

ECE teachers -also named as kaiako- should decide their activities according to principles, strands, children’s background, interest, competency and needs (Empowerment). ECE teachers should also be aware of how children’s development happens holistically. Activity aims should consider cognitive, physical, affective, spiritual, cultural and social developments all together because these developments happen interwoven and independent (Holistic development). Children can learn through responsive and reciprocal relationships with people and places, therefore ECE teachers should promote rich learning environments for realising these relationships by children (Relationship). In these rich learning environments, explorations, gaining confidence, problem solving, testing physical boundaries and meaningful learning happen if children play spontaneously (Exploration). Children can also learn where they belong to in the rich learning environments (Belonging). (Hemara, 2000; Te Whāriki, 2017) The bush explorer activity, therefore, was designed according to Te Whāriki’s principles and strands.

The ‘Bush Explorer’ Activity

This is a programme that runs for a term with the same 8-12 children around 3.5- 4 years old. The children go into the bush with an ECE teacher and two parent helpers one morning a week and on the same day. The same teacher and parent helpers go in each week for the term. The bush is in the reserve where the kindergarten is situated. It takes 2-3 minutes to walk there on the grass.

What Happens in the Bush?

The activity is play-based, child initiated and child lead. There are basic safety rules which are explained by adults at the beginning of the activity however there is no programme set by adults. The children are free to follow their own play, how, and when to play. The children themselves decide the rules of their plays and the roles they take within their play. The play is intrinsically motivated; they do it because they want to, not because they are told they have to. The play varies from group to group and week to week. The play-based learning for many children grows and develops over the time in the bush. Adults’ responsibilities in the bush are to promote a safe environment, to follow and support the children’s play.

How Does the Activity Work?

– The children gather in the kitchen of the kindergarten and prepare for the bush. This includes getting suitable water-proof gears and footwear on and getting children bags that have children’s lunch boxes and water bottles.- The teacher chooses a child as a rangatira (leader in Māori) and this child leads the group.

– The adults take into the bush a bag of equipment including mobile phone, camera, first aid kit, wipes, bug spray, ice pack, tarps, magnifying glasses, clipboards, pens, ropes, potato peeler, torches.

– The children who are leaving the kindergarten are marked on the roll and the group walks together to the edge of the bush.

– The group, especially rangatira, asks for permission from Tane Mahuta to enter the bush and waits for a reply from birds. Tane Mahuta is the god of forests and of birds, and the son of Ranginui and Papatūanuku, the sky father and the earth mother. The sign might be the singing of a tui or piwakawaka.

– Then the group go into the bush, set up a base camp and leave their bags.

– Some groups might gather for a little mat and some might go off to play or eat. This depends on the group. The adults assess the needs of the group and make decisions in consultation with the children accordingly. The children are often keen to involve the adults in their discoveries and plays. If children discover something they enthusiastically share their discoveries with adults or children may want adults to take part in the game.

-The activity takes about two hours. At the end of the time, the group gathers everything.

-They may share their day, a story, or just pack up (depending on the needs of the group).

– When leaving, the group and the rangatira thank Tāne Mahuta for allowing us to play in the bush.

– The group return to kindergarten where they get out of the bush.

– All children come back to kindergarten in two hours.

Context and Participants

The present research is based on a non-profit preschool serving 35-40 children with mixed-age grouping from 2.5 to 5 years old. The school is in a small town in Wellington and is part-time, open five days a week from 8:30 a.m. until 2:30 p.m. The ECE teachers give children the opportunity to choose their own activities daily and provide support and guidance to foster independent and collaborative explorations. The preschool gives children lots of free movement between the indoor and outdoor environments. One of these outdoor activities is ‘Bush Explorer’. The kindergarten has carried out this activity for four years.

The Researcher’s Role

The researcher who had a PhD degree in outdoor education was a female. She worked as a volunteer during the ‘Bush Explorer’ activity and an unobtrusive participant observer. The children appeared comfortable engaging with her, but mostly ignored her. This connection meant the children were already familiar with her and remained unbothered by her presence.

Data Collection and Analysis

The researcher utilised data triangulation and between-method methodological triangulation (Flick, 1998; Flick, 2006) with own observation notes and the parents’ interview notes. The activity began in March 2018 and ended in September 2018 (for 10 weeks). The parents’ interview began in October 2018 and finished in November 2018.

Observation method was used in order to collect data. The researcher worked on her own during the research and was working as a volunteer. She had responsibilities to protect and help the children during their play. The outdoor environment was a large area and not suitable to use any recording option.

There were ten children on the activity list. However, some of the children did not join the activities regularly. The five of the children joined all the activities. The interviews were held with the parents of these five children and recorded by a voice recorder. An interview protocol was prepared by the researcher. There were three groups of questions: The effects of the bush explorer activity, child background, and family background. Ethical permission was taken individually from the parents. All the interviews were transcribed.

Content analysis was used in order to evaluate the data. All observation and interview notes were coded and classified according to common expressions (Flick, 2006; Okur-Berberoglu, 2021b, in press). All data were evaluated within a case study framework.

Results

According to data, eleven different themes were determined: Problem solving, self-confidence, environmental awareness, observing and exploring, friendship and social skills, creativity, sharing experience, relaxing, having fun, conflict, and rejection. All themes, except conflict and rejection, were coherent with the literature. Sometimes, themes’ content overlapped each other because it might be seen below some observations might include different themes at the same time.

Problem Solving

Problem solving skills were mostly related to tying up and taking off the ropes or climbing up and down on the ropes. The preschoolers were very interested in tying up, hooking up and taking off the ropes. (Figure 1) From time to time the children came together and tried to solve some problems such as how to tie up a rope, how to climb up better because there were different kinds of barriers on the steep slope. Each child gave an idea to solve the problems.

One of the children set up her own rope. She worked to set the rope up for nearly half an hour on her own and she did it. She tried many times to tie up the rope in a tree. She preferred to climb up and down on her rope. (Figure 2) This girl’s father also said that he showed her before how to tie ropes together. They also had outdoor activities together.

After that girl, two boys tried to set up their ropes between trees. They tried many times to tie up the rope in the trees and at the end they succeeded. They used their problem-solving skills. One of the boys tied up the ropes together and climbed down through the steep slope. This boy’s mother also said that she could observe how his son’s problem-solving skills improved throughout the weeks because he also was very keen on doing the same thing at home.

On week four, seven children ran to the ropes and tried to tie them up to trees. Especially one of the boys and one of the girls were very keen on tying up and hooking up the ropes. The others helped them. They tried to decide how and where they could tie up and hook up the ropes. They climbed up and down on the ropes. (Figure 1) One of the mothers referred to the same output as “They did lots of problem solving and setting up things.”

Self Confidence

One of the children was new in the group. She learned how to climb up and down. She hesitated at the first stage but later she did this activity many times. I think her self-confidence increased and she liked to do this activity.

One of the mothers told how her kid’s confidence improved after the activity;

I think that his confidence probably increased in the way he was outdoors, so he did not like getting dirty or playing in the sand, getting wet, or having proper gear. He is quite happy now going out and getting his hands dirty. ….. he has confidence and also risk taking as well, climbing up the ropes. He was very enjoying doing that. I definitely think he liked the activity. The thing he liked about it most was he did something different outside of his comfort zone, he had never done before.

Another mother said her son’s self-confidence improved throughout the weeks because he did not want to climb up and down at the beginning, but later he was so keen on climbing up the steep slope. She carried on;

I think he is definitely more confident because he was aware of what’s going on around him. He did not want to put bush explorer gear on at first but later he accepted. I think he wanted to be a part of a group. He understood why he had to wear the gear otherwise he would get wet.

I think when ….. did not wear the gear, he felt a bit different. He saw the other children who wore the gear and …… wanted to get involved. He was more assertive.

One another mother explained which part of the activity was interesting for her;

I found it really is very interesting how much trust they have in the kids. There are no fences, they tell them where the boundaries are and trust. That was really quite good for me as a mum as well, to know that he followed the instructions. I was quite surprised how steep that bank was that they were climbing up because photos did not quite do that justice, just like his capabilities. What he can do and achieve was really cool.

The other mother explained how her kid’s confidence improved because of having freedom and incorporating with other children;

It is definitely being confident going out kindy, it is a changing routine for him, something new. I think definitely incorporating with the other children, he might not play in kindy environment. They did lots of problem solving and setting up things. ……I guess, the freedom that they had; how calm the teacher letting them explore and how children did respect the boundaries, having milo and cooking sausages. It is cool, it is kind of old fashion in the way, stuffs come forward and do we do not usually let kids be kids in their environment. And just observing how the teacher interacts with the children, it is very impressive. Same mother criticised how children become institutionalised because of kindergarten policies: He was at the daycare before, but they never took them out of the building. I felt like it is a very institutionalisation of children. I was really very unhappy about that. It was very exciting for me to see these trips. I looked online (kindy’s facebook) and I saw the bush explorer photos. That was very cool.

Environmental Awareness

In the second week I dug the soil and found a worm. They liked to see the worm. One of the girls said “where is my worm? I am gonna look after it.” She wanted to nurture it. One of the mothers said her son was very aware of the natural environment of the activity. They also preferred to go outdoors and talked about flowers and birds and she carried on;

I think, I wanna say ‘empathy’. When he walked through, he did not want to stand on the little plants. He would be careful looking after nature, for example looking and seeing, not snap the branches. He wanted to care about a lot more, which was nice. He was more aware of birds. He would look out the window and say “Mommy that is a special bird. That’s probably coming from the bush.

One another mother explained how children experienced the natural environment;

It was great. Probably because it is a challenge for him but also it is really important to get children outdoors and to experience different element of nature. One thing I did really like was that they are bush explorers whether it rains or shines. It does not matter whether it is a horrible day, or it was windy.

Observing and Exploring

One of the girls observed and searched the tree barks and hollows by a torch (flashlight). She explored spiders and cobwebs in the hollows. Two of the boys found dead trees and barked them off with a potato peeler. They were excited to see a spider and cobwebs around the bark. One of the boys grabbed a torch and started to explore some tree holes. He found something and yelled at the other boy. One of the girls also ran to them and the three of them looked at the same tree hole and looked for cobwebs.

One of the girls tried to dig a hole with a spade. She did not say anything about what she looked for. She dug a hole in a couple of places. One of the boys lay down on the ground and watched the branches and leaves for a while. We asked what he looked at, but he only smiled and did not say anything.

One of the boys was hooking up the rope to a tree while standing a log. He realised it was a wobbly log. He tried a couple of times and learned how to balance his body on the log. The other boy joined him, and both played a kind of balance game on the log. One was standing on one side of the log; the other boy was standing on the other side. One of the girls wanted to join them and she stood in the middle of the log. They all had fun and laughed at each other. I think they explored, solved the problem and had fun in the meantime. (Figure 4)

One of the girls found a worm and another girl found a bug. Both tried to show their animals to the other people and share their experiences. One of the girls said that she wanted to show me something. We went into the bush and she showed me a kind of natural swing. She swung on it. The children already had a swing, but she preferred to swing on her natural swing. (Figure 3) She also grabbed a magnifying glass and observed something on the ground and trees.

Friendship and Social Skills

Four of the children shovelled some pebbles on the ground and jumped over the pebbles. They created their own game and had fun together. All the children played on the balance log. It was a kind of natural seesaw. (Figure 4) There were lots of giggles and fun on the log.

One of the boys wanted to swing and asked the other boy to push him. The other boy pushed him. Same boys also preferred to play on the rope together. They chuckled and had fun. In week five some parents joined us. Dads started to set up a shelter and other children joined them. Children carried up some logs and set up the shelter all together. (Figure 5)

The four children sat on a little slope. They said that they were having a picnic all together. They pretended to eat the leaves. One of them said the leaves were ice-cream; the other said they were sandwiches. Four of them went to the shelter which they built together a couple weeks ago. Another boy joined them under the shelter. They played and chortled there all together and they seemed to have fun. After playing under the shelter, they tried to climb up the trees.

One of the mothers explained how her son’s friendship skills improved after the activity;

I think, definitely friendship because he went regularly with that group of children. He has begun talking about the children at home. He had a set time of less children. In that kind of environment, they solved problems together. It is definitely having a smaller group and doing dedicated things. I think friendship and team building, I guess.

Creativity

One of the girls created a game for herself. There was a wobbly log on the ground, and she tried to do a balanced walk on it. She walked back and forth a couple of times. (Figure 4) Children played with trees for a while. Adults helped children and they built a wooden bridge between trees all together.

Two boys created a game by themselves. They picked up some rocks one by one from the ground and threw them down from a hill. Another boy joined them after a while. They tittered and had fun.

One another girl had a magnifying glass and torch. She showed her mother how to look for spiders and spider webs. Same girl made a fish hook with a stick and a little rope and made a monster trap with a rope. All the children passed under it. They had fun.

Sharing Experience

In week five, the day started as usual, later I realised that three parents were coming with us into the bush. I asked the parents why they wanted to join the activity. They said that their children asked them to come to the bush and show them what they did. Later I remembered some parents joined us in the previous weeks. Probably their children might invite them, too. Parents joined us voluntarily. It was interesting because children want to share these outdoor activity experiences with their parents.

One of the boys told me with excitement how he and his friends dug a hole and found a treasure under the soil. Same boy showed dad how to climb up and down on the rope. This boy’s mother said his outdoor experience was mostly based on playgrounds, not natural outdoor settings. He might be so excited about what he saw and discovered in the natural settings and might share his experiences.

One of the mothers said she and her son came to the bush after hours and her son showed her how to climb up and down on the steep slope. The other mother explained how her kid tried to share his experience as“Guess what we did at the bush explorer activity today?” or he would say “We were digging in the gravel” or he would talk about a scout hall which is down to the bush.

Relaxing

One of the boys lay down on the ground and watched the branches and leaves for a while. We asked what he looked at, but he only smiled and did not say anything. One another boy preferred to lie down and watch the trees from time to time. He said he wanted to sleep there. Three of the boys also lay down and watched the trees and branches for a while.

Having Fun

Two of the boys were hungry. They sat on the mat and ate something. They set up a play with their food containers while eating something. They chuckled and laughed at each other many times.

Two boys created a game by themselves. They picked up some rocks one by one from the ground and threw them down from a hill. Another boy joined them after a while. They tittered and had fun. Except for two of the children, the others played ‘Three Little Pigs’ story in the bush. They had fun and sniggered many times. One girl and one boy played a balance game together; they played on the ropes, too. The rest of the group seemed to have fun and played together in 2-3 groups.

Conflict

Sometimes conflicts occurred among children. They had arguments when they wanted to play on the same tree, rock or swing at the same time.

Rejection

One of the boys and one of the girls did not like the activity very much. Sometimes they did not even come to kindergarten and join the bush explorer activity. If they joined the activity, they refused to put the bush gears on and cried not to go to the bush. Both did not want to be a leader, either. Last week of the activity, the girl accepted to be rangatira but did not want to put the leader’s cape on her.

I offered the boy to wander in the bush. He held my hand and walked for a while in the bush. I started to tell a story about the Gruffalo. I asked whether he knew the Gruffalo and liked him or not. He said ‘yes.’ I carried on the story while asking questions ‘do you know where the fox/snake/owl lives? What does the Graffalo look like?’. He liked my questions and answered all of them correctly. He already knew the Gruffalo story. Later I offered him to make a shed. We picked up some sticks and put them on the shed. (Figure 5) He liked to pick up the sticks and put them on the shed. He went into the bush and picked some sticks by himself while smiling. He showed me how his sticks were tall and heavy. He said, ‘we made an underground house.” After a while, he seemed sad again. I asked why he looked sad, and he said, ‘the bush is very boring, and I am bored’. I asked ‘why?’. He said, “here is boring because there is no toy.” I said ‘everything in the bush is a toy. Look at all those sticks, all are toys for us.”. He said, “sticks are cool but there is no toy here.” I asked him “Do you usually play outside?” He said, “not really.”

The girl cried a couple of times and said that the bush was muddy. She did not like to go to the bush and missed her mummy.

Discussion and Conclusion

The bush explorer activity showed expected outputs/themes mentioned in the literature (Table 1) and New Zealand ECE programme, Te Whāriki. Te Whāriki (2017) wants ECE teachers to present a rich learning environment for preschoolers in order to have cognitive (problem solving, exploring, observing), physical (self-confidence), affective (having fun), and social developments (friendship and sharing experiences) all together because these developments happen interwoven and independent (Holistic development). All these themes are also related to Māori pedagogies and meaningful learning because children are seen as confident and competent learners and these themes happen by a rich learning environment (Hemara, 2000). As can be seen in Table 1, the results of this research are very coherent with the context, benefit and aims of outdoor education defined by Brodin& Lindstrand (2006), Cooper (2015), and Waite (2009).

Self-confidence is also highlighted by Cooper (2015), Louv (2005) and Okur-Berberoglu (2021a). These authors mention physical self-confidence and testing physical boundaries. The main difference between natural outdoor settings and playgrounds is the physical structure of the place. On the playground, children can learn and memorise how to handle each problem after a while because it is a stable environment. However, in the natural outdoor settings, the physical condition or problem situation might change according to weather, season, or growing up the trees/plants. (Okur-Berberoglu, 2021a) Children might need to solve a new problem each time and this might affect their physical and emotional self-confidence (Rousseau, 1979). The other important point was the teacher’s trust, attitude and behaviours to children as the mothers mentioned in the results section. Children could do whatever they want within some rules and they obeyed the rules. This kind of situation might be effective for the improvement of emotional self-confidence and affective development of children.

Affective development also includes environmental awareness and emotional well-being (Cooper, 2015; Okur-Berberoglu, 2017a, 2017b; Waite, 2009;). The bush explorer activity was not based on environmental aims, however children realised that there were also different creatures around them and wanted to share what they found with me or their parents. One of the mothers said the activity was also effective on the empathy development of her son. Nurturing and sharing are also classified under social and emotional well-being by Waite (2009) (Table 1). Most of the children have previous outdoor playground experiences before according to interview notes. However, it was very interesting and exciting to experience natural outdoor settings and that was why the children wanted to share these experiences with their parents (Results).

Sharing experiences were also observed among children. Children might improve their friendship and social skills by sharing experiences (Cullen, 1998; Engdahl, 2005; Lindstrand, 2005; Waite, 2009). Experiences were shared in two ways. One of them was by exploring and observing. The other one was by having fun. When the children discovered, observed and explored interesting subjects or plays, they shared them. When they shared something, they also had fun therefore they improved their social skills. They moved collectively as well as they moved individually while creating something. My observations were supported by mothers’ interviews as well, because they also underlined how being in a small group, solving problems together built friendship and a team.

Another theme is creativity which is mostly mentioned by Louv (2005) and Okur-Berberoglu (2021a). Especially Louv (2005) Rousseau (1979) and Carson (1956) make a point that children do not need a structured play or education outdoors. They might play whatever they want and create any play or art according to their imaginations. The children in this study created their own plays or tools so they were very busy.

The children were not bored because they were busy and the bush gave them the opportunity for relaxing (Cooper, 2015; Rousseau, 1979) and having fun (Carson, 1956; Louv, 2005; Okur-Berberoglu, 2021a; Wilson, 1996;). Some children just watched the trees and flowers without any reason or chatted with the other kids. As a researcher or adult, it might not make sense for us however, this kind of relaxing time might trigger children’s creativity and children might be less stressed (Louv, 2005; Okur-Berberoglu, 2021a).

Louv (2005) and Okur-Berberoglu (2021a) suggest experimental studies with control groups on unstructured outdoor settings. There is no control group for this study, however it is possible to see Louv’s expected outputs and Okur-Berberoglu (2021a)’s research results at the end of this study. More studies related to unstructured outdoor settings are needed. Researchers might find different outputs by the experimental studies with control groups.

There are two different outputs which are not mentioned in the literature: conflict and rejection. Conflict might be accepted as normal according to preschoolers age group because they are still learning how to share in different environments. Rejection might be a quite interesting theme because this output might also be related to how children are brought up. It is expected for children to use their creativity skills while playing outdoors however one of the children wanted to play with his own toys at home. I could not talk to this kid’s parents and this situation might be a research question on its own.

One of the interesting outputs of this study is a mother’s criticism about institutionalism of children because of kindergarten policy. She said that children just played between walls and indoors. This mother was quite happy for her kid to experience this activity and outdoor settings. This kid went to a daycare in a city centre before and the daycare did not organise these kinds of activities. Waite (2009) and Lindstrand (2006) say that ECE curriculum in UK and Sweden mention how important outdoor education is for preschoolers; however teachers do not know how to use outdoors and evaluate the outputs. The kindergarten policies, teachers’ outdoor backgrounds or where the kindergartens are situated might be studied in future research.

Recommendations

I asked some questions related to technology in the interview protocol because there are some studies related to child obesity and outdoors (Gerritsen, 2006; Ministry of Health, 2017; Raustrop et al, 2012: Young, 2017) or media addiction, child obesity and outdoors (Okur-Berberoglu, 2015c) should be evaluated one by one. However Okur-Berberoglu (2021a) observes how her kid stayed away from media platforms when the kid focused on playing outdoors.

Contemporary play environment of children and its effect on children might be evaluated in further studies. The results of this study should not be generalised, but similar studies should be carried out in different regions or countries.

Preschoolers might show different outputs at different ages. This kind of study might be repeated for different age groups.

According to my observations and interviews, parents’ backgrounds might also be effective on children’s outdoor perspectives. Further studies that include parents or grandparents and preschoolers might be conducted.

If the activity is effective on empathy development , this kind of activity might be used for environmental aims in further studies (Okur-Berberoglu, 2015d).

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank the preschool community- including the teachers, parents and children. Ethical permission was taken by parents individually. There is no conflict of interest within this study.

References

Ali, A., Pigou, D.,Clarke, L., & McLachlan, C. (2017). Literature review on motor skill and physical activity in preschool children in New Zealand. Advances in Physical Education, 7, 10-26. https://doi.org/10.4236/ape.2017.71002

Brodin, J. & Lindstrand, P. (2005). Children’s learning in outdoor environments. Paper presented at the Early Childhood 11th Biennal Conference, Cyprus University, Nicosia, August 23 rd -26 th 2005.

Brodin, J., & Lindstrand, P. (2006). Inclusion of children in outdoor education. Learning in Motion, Report I., TKH- report No. 43, Child & Youth Science. Stockholm: Stockholm Institute of Education.

Burke, R. (2008). Becoming individuals together: Socialisation in the Japanese preschool. Sites: a journal of social anthropology and cultural studies, 5(2), 135-160.

Carson, R. (1956). The sense of wonder. New York: Harper & Row.

Conezio, K., & French, L. (2002). Science in the preschool classroom. Young children, 57(5), 12-18.

Cooper, A. (2015). Nature and the outdoor learning environment: The forgotten resource in early childhood education. International Journal of Early Childhood Environmental Education, 3(1), 85-97. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1108430.pdf

Cullen, J. (1988). Preschool children’s learning strategies. Set: research information for teachers, 2.

Duignan, M., Signal, L., & Thomson, G. (2014). Good intentions, but inadequate practices-sun protection in early childhood centres, a qualitative study from New Zealand. NZ Med J, 127, 40-50. Retrieved from http://www.nzma.org.nz/journal/read-the-journal/all-issues/2010-2019/2014/vol-127-no.-1389/5998

Engdahl, K. (2005). We want to live – live forever. An empirical study on children’s interaction and play on two preschool playgrounds]. Report 41, TKH, Stockholm Institute of Education.

Flick, U. (1998). An introduction to qualitative research. London: Sage.

Flick, U. (2006). Triangulation. In V. Jupp (Ed.), The Sage dictionary of social research methods (305-306). London:Sage.

Fröbel, F. (1895). Friedrich Froebel’s pedagogics of the kindergarten (Vol. 30). D. Appleton.

Gerritsen, S. (2016). Nutrition education for early childhood managers, teachers and nursery cooks: a prerequisite for effective obesity prevention. Public Health, 140, 56-58. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2016.05.025

Hammerman, D. R., & Hammerman, W. M. (1973). Teaching in the outdoors. Minneapolis: Burgess Publishing Company.

Hemara, W. (2000). Māori Pedagogies. Wellington: New Zealand Council for Educational Research.

Holdom, J. (2018). Science, technology, engineering and mathematics learning through the lens of Te whāriki: He whāriki mātauranga mō ngā mokopuna o Aotearoa: Early childhood curriculum. He Kupu 5(3), 1-11. Retrieved from https://www.hekupu.ac.nz/sites/default/files/2018-05/03%20Holdom.pdf

Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development, Prentice Hall Inc., EnglewoodCliffs, New Jersey. Retrieved from http://academic.regis.edu/ed205/Kolb.pdf , 03.06.2011

Kraft, R. J. & Kielsmeier, J. C. (1995). Experiential learning. Iowa: Kendall/ Hunt.

Ku, H. Y. (2011). Measuring the physical activity of children aged 3 to 7 years (Doctoral dissertation, University of Otago).

Kumar, K., & Whyte, M. (2018). Interactive science in a sociocultural environment in early childhood. He Kupu, 5(3), 20-27. Retrieved from https://www.hekupu.ac.nz/sites/default/files/2018-05/04%20Kumar%20and%20Whyte.pdf

Lindstrand, P. (2004). Playground and outdoor play. A literature review. Research report 42 in the series TKH. Stockholm: Stockholm Institute of Education: Department of Human development, learning and special education.

Louv, R. (2005). Last child in the woods. North Carolina: Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill.

McLachlan, C. (2013). Children’s learning and development in New Zealand: physical, cognitive and socio-emotional perspectives. The engine of the new New Zealand lecture series. Retrieved from http://www.masseyuniversity.co.nz/massey/fms/Colleges/Institute%20of%20Education/Documents/2013/web%20copy_Claire%20McLachlan%20commemorative%20book.pdf

McClain, C., & Vandermaas-Peeler, M. (2016). Outdoor Explorations with Preschoolers: An Observational Study of Young Children’s Developing Relationship with the Natural World. International Journal of Early Childhood Environmental Education, 4(1), 37-53. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1120151.pdf

Ministry of Health (2017). Sit Less, Move More, Sleep Well: Active play guidelines for under-fives. Wellington: Ministry of Health. Retrieved from https://www.health.govt.nz/system/files/documents/publications/active-play-guidelines-for-under-fives-may17.pdf

O’Brien, N. (2015). Strategies for teachers developing strategies for mathematics in early childhood education. He Kupu, 4(1), 18-22. Retrieved from https://www.hekupu.ac.nz/sites/default/files/2017-10/Strategies-for-teachers-developing-strategies-for-mathematics-in-early-childhood-education.pdf

Okur, E. (2012). Outdoor experiential teaching: Ecology application. Published PhD Thesis. Canakkale Onsekiz Mart University, Turkey.

Okur-Berberoglu, E., Guder, Y., Sezer, B., & Yalcin-Ozdilek, S. (2013). An outdoor hydrobiology activity’s effect on students’ affective perspective, case study: Canakkale, Science Camp. Kastamonu Education Journal, 21(3), 1177-1198.

Okur-Berberoglu, E. (2014). The effect of ecological dynamics model on behavioural change, direct and indirect actions. Turkish Journal of Teacher Education, 3(1), 1-17.

Okur-Berberoglu, E. (2015a). The Effect of Ecology Based Environmental Education on Environmental Knowledge Gaining of In-Service Teachers. Turkish Journal of Teacher Education, 4(1), 30-49.

Okur-Berberoglu, E. (2015b). The Opinions of the in-service teachers to ecopedagogy-based environmental education depend on holistic perspective. Mersin University Journal of the Faculty of Education, 11(3), 732-751.

Okur-Berberoglu, E. (2015c). Children-teenagers, media addiction and outdoor education. The Journal of Hasan Ali Yücel Faculty of Education, 12(2), 45. Retrieved from http://dergipark.gov.tr/iuhayefd/issue/8803/110050

Okur-Berberoglu, E. (2015d). The Opinions of the in-service teachers to ecopedagogy-based environmental education depend on holistic perspective. Mersin University Journal of the Faculty of Education, 11(3), 732-751.

Okur-Berberoglu, E. (2017a). Ecological dynamics model and ecopedagogy-based outdoor experiential education. International Electronic Journal of Environmental Education, 7(2), 134-151.

Okur-Berberoğlu, E. (2017b). Outdoor experiential environmental education: An adult-centred intervention for the affective domain. International Electronic Journal of Environmental Education, 7(1), 34-58.

Okur-Berberoglu, E. (2021a). Some effects of unstructured outdoor plays on a child: A case study from New Zealand. International Electronic Journal of Environmental Education, 11(1), 58-78.

Okur-Berberoglu, E. (2021b). The Evaluation of Sustainable Diet within ‘The Big Ward’in Aotearoa, New Zealand: “Clean, Green and Fat New Zealand”. World Futures, 1-19.

Okur-Berberoglu, E. (in press). Evaluation of humanistic curriculum within ‘Accepted’ movie. International Journal of Educational Reform.

Oliver, M., Schofield, G. M., Kolt, G. S., & McLachlan, C. (2007). Physical Activity in Early Childhood: Current State of Knowledge. New Zealand Research in Early Childhood Education, 10, 47-68. Retrieved from https://www.childforum.com/images/stories/Oliver_et_al_2007.pdf

Oliver, M. (2008). Physical activity in New Zealand preschoolers: amount, associations, and accounts (Doctoral dissertation, Auckland University of Technology).

Raustorp, A., Pagels, P., Boldemann, C., Cosco, N., Söderström, M., & Mårtensson, F. (2012). Accelerometer measured level of physical activity indoors and outdoors during preschool time in Sweden and the United States. Journal of physical activity and health, 9(6), 801-808. Retrieved from https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/7257/5d82ccd7606b17fa2d64efc8e1a579aa4e34.pdf

Rousseau, J. J. (1979). Emile or on education (Translation by Allan Bloom). USA: BasicBooks

Siraj-Blatchford, J. &; MacLeod-Brudenell, I. (1999). Supporting science, design and technology (Editors: Vicky Hurst and Jevefer Joseph). Buckingham: Open University Press.

Stephenson, A. (1999). Opening up the outdoors: A case study of young children’s outdoor experiences in one childcare centre. M. Ed Thesis, Victoria University of Wellington. Retrieved from http://researcharchive.vuw.ac.nz/bitstream/handle/10063/917/paper.pdf?sequence=1

Stine, S. (1997). Landscapes for learning. New York: John Wiley&Sons, Inc.

Te Whāriki, Early Childhood Curriculum of New Zealand (2017). Ministry of Education 2017 Revision. Retrieved from https://www.education.govt.nz/assets/Documents/Early-Childhood/Te-Whariki-Early-Childhood-Curriculum-ENG-Web.pdf

Vandermaas-Peeler, M., & McClain, C. (2015). The Green Bean Has to Be Longer than Your Thumb: An Observational Study of Preschoolers’ Maths and Science Experiences in a Garden.

International Journal of Early Childhood Environmental Education, 3(1), 8-27. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1108468.pdf

Wagner, C. (2000). Planning school grounds for outdoor learning. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED442266.pdf

Waite, S. (2009, April). Outdoor learning for children aged 2–11: Perceived barriers, potential solutions. In Fourth International Outdoor Education Research Conference, La Trope University, Beechworth, Victoria, Australia (pp. 15-18). Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Sue_Waite/publication/242494391_Outdoor_learning_for_children_aged_2-11_perceived_barriers_potential_solutions/links/0deec5300881a079f8000000.pdf

Wilson, R. A. (1996). Starting early: Environmental education during the early childhood years. ERIC Digest. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED402147.pdf

Yalcin, S. & Okur, E. (2011). Mobile phone and child. Journal of Education for Life, 110 (2), 2-11.

Yalçın, S., & Okur-Berberoğlu, E. (2014). The effects of electromagnetic field (EMF) education within ecopedagogy on EMF awareness. Pamukkale University Journal of Education, 35 (1), 143-156.

Yıldırım, G., & Akamca, G. Ö. (2017). The effect of outdoor learning activities on the development of preschool children. South African journal of education, 37(2). Retrieved from https://www.ajol.info/index.php/saje/article/download/157298/146909

Yildirim, A. & Simsek, H. (2006). Qualitative methods for social science. Ankara: Seckin Publication.

Young, L. (2017). Under 5 energize: Improving child nutrition and physical activity through early childhood centres (Doctoral dissertation, Auckland University of Technology). Retrieved from http://aut.researchgateway.ac.nz/bitstream/handle/10292/11003/YoungL.pdf?sequence=4&isAllowed=y

Zanovello, I. (1999). Outdoor and environmental education centres: A case study of Starthcona Park Lodge and Outdoor Education Centre, British Columbia, Canada. A Master Degree Thesis, Faculty of Environmental Design, The University of Calgary, Alberta.

Emel Okur-Berberoglu holds a PhD degree in ecopedagogy- based programme development. Her research and writing interests focus on ecopedagogy-based environmental education and outdoor education. She is also interested in science philosophy.

Emel Okur-Berberoglu holds a PhD degree in ecopedagogy- based programme development. Her research and writing interests focus on ecopedagogy-based environmental education and outdoor education. She is also interested in science philosophy.