Empowering Staff Members to Improve Student Learning in Sustainability Projects: The “We Are All Educators” Workshop at Harvard University

Link to the JSE General Issue May 2022 Table of Contents

Link to the JSE General Issue May 2022 Table of Contents

Article PDF

Abstract: Staff members play an important role in guiding students through living lab sustainability projects at Harvard University. Since there are significant opportunities for co-curricular learning in these settings, we created the “We Are All Educators” professional development workshop to empower those staff members to optimize and track student learning throughout these projects. In this case study, we will briefly summarize key principles of CCL and discuss its benefits as a tool for sustainability education in higher education. We will also describe our planning and implementation process for the workshop, the content of our training materials, and the results. Finally, we will end with key takeaways, as our workshop may be applicable to co-curricular learning in a variety of higher education contexts.

Keywords: Co-curricular learning, living lab, experiential learning, sustainability grants, professional development, higher education

Introduction

Sustainability programs at colleges and universities around the world are aimed at addressing global sustainability challenges at the campus-level. Many of these institutions have established robust programs to encourage students, faculty, and staff to use their campus as a testbed to pilot innovative technologies and strategies – often called “living lab” or “campus as lab” initiatives. Not only does this framework allow colleges and universities to tap into new ideas and pilot replicable models that can later be institutionalized more broadly, but this also provides a unique opportunity for co-curricular learning. Allowing students to lead sustainability projects in these real-world settings can enhance and broaden the learning that occurs (Briggs et al., 2019). In fact, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine released a report in 2020 calling for more experiential learning to optimally teach key sustainability competencies (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2020).

At Harvard University, the “living lab” concept has been central to its sustainability vision and work for years. The University community has been working on-the-ground and across disciplines, generating new discoveries that can be used to inform the University’s implementation of its Sustainability Plan in ways that can be replicated and applied on the local, regional, and global level. For more than a decade, Harvard University administration has funded a Student Sustainability Grant Program that supports project teams who aim to contribute to Harvard’s commitment to climate, equity, and health. These projects often involve partnerships between students and staff, such as rain gardens and micro-prairies installed in partnership between students and Harvard Landscaping. In 2016, Harvard expanded its Living Lab Program by launching the Campus Sustainability Innovation Fund, which brings students, faculty, and staff together to carry out research projects that aim to have an impact on operations and decision-making at Harvard’s campus and provide scalable solutions that can be applied to other organizations.

In a rapidly changing world, it is increasingly difficult to predict what jobs will exist in the future. Nevertheless, executive leaders in various industries have cited 21st century skills such as communication, collaboration, creativity, and critical thinking as consistently important (National Education Association, n.d). As the link between K-12 classrooms and the job market, universities are responsible for training young adults in this global society. Co-curricular learning (CCL) has evolved as a valuable higher education tool (Kwon et al., 2020) as it intentionally structures learning experiences outside of the classroom, providing students authentic opportunities to engage in real-life contexts. For example, at Harvard, CCL opportunities in sustainability include student-led grant projects that are supported by faculty and staff supervisors, internships, and peer-to-peer education programs. Learning has always been a major benefit of Harvard’s “living lab” programs, but we recognized a challenge in that these student learning objectives or outcomes were not being systematically tracked or optimized.

In 2019, Harvard Library and the Office for Sustainability (OFS) at Harvard University received a grant from the Harvard Initiative for Learning and Teaching (HILT) to address this challenge by training staff advisers who work with students in sustainability-related programs, projects, or internships. We wanted to make sure that our students were supported in this co-curricular learning in order to better prepare them for the future. Our year-long project culminated with a series of online workshops called “We Are All Educators” with the mission of helping staff members create effective learning experiences for students outside of the classroom. In this case study, we will briefly summarize key principles of CCL and discuss its benefits as a tool for sustainability education in higher education. Then, we will describe our planning and implementation process, the content of our training materials, and the results of the “We Are All Educators” Workshop. Finally, we will end with future implications, as our workshop may be applicable to experiential learning in fields outside of sustainability. Our hope is that this case study can serve as a replicable model for other universities interested in developing staff skills as educators so that student learning can be enhanced in the wider university ecosystem.

Co-curricular Learning and Sustainability in Higher Education

Co-curricular learning is often confused with extra-curricular activities since both involve informal student learning experiences outside of the classroom. However, CCL has a key differentiator: it is structured and intentionally tied to learning objectives (Wankel & Wankel, 2016). Learning objectives are statements that describe what students will learn by the end of an experience. While these objectives can be knowledge-based, CCL provides opportunities to support objectives that transcend factual knowledge—in particular, CCL fosters development of communication, collaboration, and systems-thinking skills, among others (Andersen, 2015). CCL provides rich learning opportunities because students are applying their knowledge while reflecting on their processes to solidify their learning. CCL therefore takes advantage of the benefits of experiential learning (Kolb, 1984), in which a learner goes through four stages: concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualization, and active experimentation (Barth et al., 2007; Briggs et al, 2019). In other words, learning happens through the experience. These experiences are often presented in a form of a project and thus, borrow design elements from project-based learning. Project-based learning is a pedagogical practice in which students apply their knowledge to solve real-world problems (Everett et al, 2018; Lee et. al, 2014).

Gramatakos and Lavau (2019) noted the limited research on co-curricular learning for sustainability education in higher education, pointing out that most of the attention is focused on how to integrate sustainability into the formal curriculum. Their study found evidence for the importance of student-led informal and co-curricular learning opportunities in sustainability. CCL can support a range of learning dimensions, including critical thinking around sustainability, engaging with new perspectives, and knowing through doing (Gramatakos & Lavau). Barth et al. (2017) found that informal, experiential learning experiences can contribute to the development of key competencies for sustainable development among higher education students. Living-learning programs that combine curricular and co-curricular learning can lead to increased awareness, deeper understanding, and small behavior changes related to sustainability (Lewis et al., 2019). Student-led CCL can also support and reinforce formal curricular learning around sustainability (Briggs et al, 2019).

Several institutions such as Roskilde University and University of the West of England have conducted studies on the benefits and barriers related to co-curricular learning in higher education (Andersen, 2015; Sara, 2015). These studies highlight the importance of having an adviser to guide the students so that their experiences lead to effective learning outcomes. As noted earlier, reflection is a critical component of the experiential learning process, and that reflective process needs to be supported in CCL activities (Briggs et al., 2019). While oftentimes, that support is seen as coming from teaching or other academic staff (Barth & Rieckmann, 2012; Briggs et al.; Everett et.al, 2018), these advisers may also be non-teaching staff members within a university. Scholars have identified professional development for teaching staff as essential to furthering the goals of sustainability education in both higher education (Barth & Rieckmann; Everett et al.) and K-12 (Ernst et al., 2020; Redman et al., 2018). While faculty members are seen as core educators in post-secondary institutions, non-teaching staff members must also be seen as educators; in addition to serving in their operational roles, they are directly engaging with students who have specific goals. In other words, staff members are critical contributors to the university’s learning mission and are becoming increasingly important due to the skill-based nature of co-curricular learning and its growing role on campuses. Given their evolving roles, how can universities enable staff members to guide students in CCL in higher education?

The “We Are All Educators” Workshop

Problem

When properly guided, CCL is a powerful tool as students are more likely to be intrinsically motivated and thus, more likely to internalize learning. These experiences also provide a structure for students to be reflective and self-guided learners (Briggs et al., 2019). As Briggs et al. note, this reflection is not necessarily automatic; it must be deliberate and staff support is critical. The Harvard OFS found that they were often asked by staff members supporting living lab projects about how they should design and then judge a student project from an educational-outcomes perspective. Staff felt that, while they had expertise in sustainability, they did not feel the same level of expertise with creating and supporting structures for learning. Given that professional development can be an effective strategy for increasing faculty members’ capacity at integrating sustainability into the formal curriculum (Barth & Rieckmann, 2012), we posited that continuing education could also help university staff. At Harvard, the majority of the support for teaching and learning was aimed at faculty, rather than staff, so we saw a need for the development of a training program specifically targeting this unserved population.

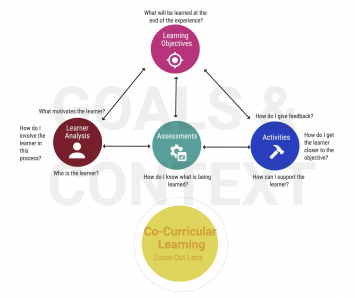

To prepare advisers to better support student learning through CCL, we designed a workshop for Harvard staff members to learn to intentionally apply education-based practices in CCL. The framework for developing this workshop was based on a model developed by the first author for staff development programs for Harvard librarians (see Markman et al., 2021). This model, which we named the Zoom-out Lens (see Figure 1) describes the interconnection between the learners, learning objectives, assessments, and instructional activities. In the background are the goals and context for the learning. In the case of the We Are All Educators workshop, the goals were driven by the needs identified by the Harvard OFS, as described above.

Figure 1. Zoom-out lens framework that guided the workshop development and was used as a pedagogical resource.

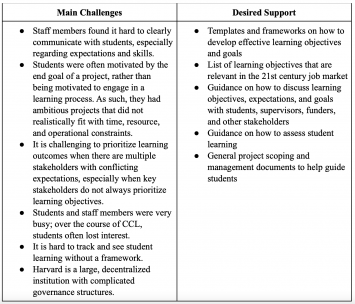

Following this model also required us to analyze the needs of our learners, in this case staff working across the University supporting student sustainability projects. One of the main goals for the workshop was to increase staff confidence in supporting the learning aspect of sustainability-related CCL projects across Harvard. To develop our own learning objectives related to that goal, we conducted a needs assessment of our target learners in the form of two focus groups. The goal of these focus groups was to understand staff members’ experiences with students in the CCL context, the challenges they faced while trying to integrate learning objectives into student projects, and the types of support they would like to receive in the future. We were intentional to not focus on logistical and personnel issues with faculty members and students, as we determined those were out of scope for the workshop we were planning to develop. A total of 12 staff members representing four Harvard schools and three Harvard central administrative departments, including the Office for Sustainability, participated in the two focus groups. Through our analysis of our focus group transcripts, we identified common challenges facing staff advisers as educators and supports that would most likely benefit their work (see Table 1).

Each university provides a unique context in which the staff members operate; staff members, therefore, will experience different barriers. While we provide a narrative of how we conducted our staff member training at Harvard University, we suggest that universities first conduct their own needs assessments and then customize their training accordingly. For example, Harvard University is a decentralized institution with 12 degree-granting schools and consequently has complicated governance structures. As projects in the CCL context span across several departments and sometimes schools, staff members faced specific challenges helping the students navigate the Harvard ecosystem.

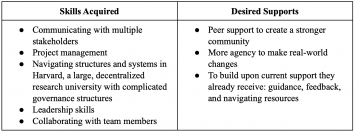

Because students are the primary focus in CCL, we also felt it was important to get insight on how Harvard students currently experience CCL. We conducted a survey for students involved with the Office for Sustainability grants, projects, programs, and internships. Our survey was focused on identifying the top skills they acquired from their experience, whether they felt supported, and what further support they desired. Because learning is also tied to motivation (Blumenfeld et al., 2006), we also asked about their motivations to engage in sustainability programs. A total of 18 undergraduates from both the current year and past year’s programs responded to the survey. A summary of the findings from their responses is in Table 2.

In some cases, the students’ reports of skills they gained were similar to the skills our staff participants thought students should or would learn through their CCL experiences, so we were able to draw on these student responses in developing workshop materials.

Workshop design

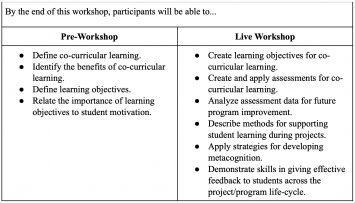

Our needs assessment brought us to focus on the following problem statement that guided our workshop development process: staff members lacked training on how to set learning objectives and realistic project expectations, assess learning, and continually support students throughout the CCL program lifecycle. Our theory of change was that if we provided a repository of resources and training workshops, then staff members would be more equipped and feel more confident in guiding student learning in co-curricular learning environments. This would translate into enhanced student learning on campus. Our needs assessment of our target learners also provided valuable information about how they preferred to engage in training. In particular, participants stressed that they were all busy and had limited time, and several noted other University staff trainings that made use of a combination of online pre-work and live training as being a desired format. Based on this feedback, we created learning objectives and divided them between a pre-workshop module and the live workshops (see Table 3).

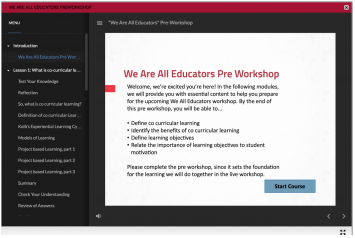

Our pre-workshop module was an online module that could be accessed asynchronously through the University’s staff-facing learning management system (see Figure 2). Digital accessibility guidelines informed our learning design and the eLearning content creation software we selected (Articulate360: Storyline). In keeping with our Zoom-out Lens framework, we aligned our workshop learning objectives, and the instructional activities to achieve these objectives (including workshop structure) with the needs and motivations of our learners as discovered through our learner analysis.

We originally prepared two options for our live interactive training: 1) two 2-hour workshops and 2) one 4-hour workshop. These workshops were scheduled to take place in March and April 2020. The goal for two versions was to compare the formats, from both a participant satisfaction and a learning perspective, to inform future iterations of the training. Due to COVID-19, however, we had to redesign our workshops to be delivered online and were not able to run two versions of the workshop. Instead, we pivoted to offer one version, organized as two, 2-hour synchronous sessions delivered one week apart via the Zoom video conferencing platform in April 2020. This pivot also required us to redesign many of the active learning techniques we were planning to use, which relied on the use of whiteboards, sticky notes, and in some cases physical movement around a classroom, to the new Zoom environment. We utilized Zoom breakout rooms, chat, and screen share of Google Docs to implement collaborative and interactive activities in the new online classroom. While this unforeseen pivot was a challenge, the online format provided an opportunity to explore how to scale this type of training for other staff members across the university in the future.

In summary, the goal of the We Are All Educators workshop was to develop skills and background knowledge to help staff better support student learning in sustainability focused CCL activities at Harvard. In keeping with our Zoom-out Lens framework (Figure 1), the instructional activities we designed for the live session, in concert with the pre-workshop online module, were aligned with our learning objectives and provided staff members a framework to better support student learning in the CCL experiences they supervised. In addition, we featured the Zoom-out Lens during the workshop as a suggested framework for our participants to use in their CCL experiences with students. We also provided templates and frameworks that would help staff members create, assess, and support learning. It was critical to spend the majority of the workshop developing skills and background knowledge the staff members would need before they could effectively use these resources, which was a specific request in our focus groups. After the workshop, we collated these resources in an online repository: https://green.harvard.edu/we-are-all-educators-workshop-repository. The repository includes:

- Workshop training materials (slides, handouts, etc.)

- Example learning objectives that are based on 21st-century skills frameworks.

- Common formative and summative assessments and activities for use in CCL contexts.

- Rubrics for assessing learning in CCL.

- Templates to support student learning about systems thinking, stakeholder mapping, logistical frameworks, strategic planning, and project planning.

Workshop assessment

In total, 13 staff members representing five different Harvard central administrative offices and one Harvard school completed the pre-workshop module and participated in some of the live workshop sessions. Of those, 11 staff members attended both online workshop sessions; below we report on data from the 11 who completed both sessions.

Before our participants began their training, they were assessed via a pre-test survey on their self-reported confidence in and proficiency with learning objectives. We used this as a baseline to estimate the efficacy of the training; the same survey was repeated, along with additional questions to solicit general feedback, after the participants attended our workshops.

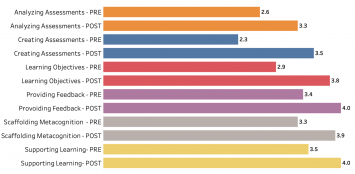

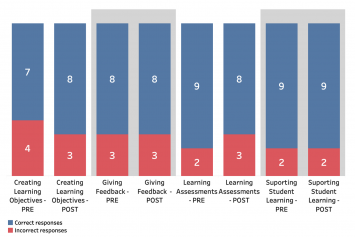

Confidence. We assessed the staff members’ self-confidence on our workshop learning objectives using a Likert-type scale (see Figure 3). In our analysis, we looked at the aggregate confidence rating before and after the workshop. In addition, we identified the growth in confidence before and after the workshop. Overall, staff member confidence in our learning objectives increased from the pre- to post-test, with the highest average growth in “creating learning objectives” and “creating and applying assessments” and the lowest average growth in “supporting student learning.” It is important to note, however, that most staff members were already moderately confident in “supporting student learning” before the workshop. In fact, by the end of the workshop, staff members were the most confident in “supporting student learning” and “giving effective feedback”.

Figure 3. Participants’ mean self-reported confidence on learning objectives, pre- and post-test. 1 = Not at all confident, 2 = Slightly confident, 3 = Moderately confident, 4 = Very confident, 5 = Extremely confident

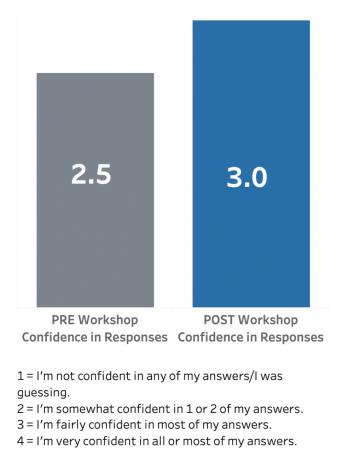

Proficiency in skills. We assessed the staff member’s proficiency in skills covered in the live session via four knowledge-based multiple-choice questions aligned with several of our learning objectives. In our analysis, we looked at the number of respondents who selected correct vs. incorrect answers per learning objective. In addition, we also asked the respondents to rank their level of confidence for their provided answers in order to account for the possibility of guessing or picking an answer at random.

Most participants (64%) stayed the same in their responses to the knowledge questions, with the highest improvement in the question related to “creating learning objectives” and the least improvement in “creating and applying assessments” (See Figure 4). This is not surprising since the sudden pivot from live to virtual training that resulted from COVID-19 limited our previously planned activities for this learning objective. We had to adapt these activities, which were intended to be hands-on, to be covered more via lecture and discussion in the workshop. This might have limited the workshop’s efficacy in helping participants create and apply assessments. However, participants still reported becoming more confident in the learning objective related to “creating and applying assessments.” It may be then that the knowledge question was not sensitive enough to capture the gains that participants themselves reported.

Overall, 45% of the participants indicated that their confidence in their aggregate responses to the knowledge questions did increase after the workshop. As a result, the average confidence increased as well (see Figure 5).

Figure 5. Participants’ pre- and post-test self-reported confidence in knowledge question responses.

Our data to properly assess our participants’ proficiencies in the skills outlined in our learning objectives has limitations. First of all, our proficiency test was binary. In other words, our analysis only shows whether the respondents chose correct or incorrect answers. It does not show granular details such as whether respondents chose better answers. Furthermore, the proficiency test was predominantly based on knowledge rather than participants’ actual behavior.

Workshop feedback

In our post-survey, we asked participants to compare their learning outcomes with their expectations on a four-point scale (i.e: “I learned more/about as much/same/less than I expected to learn”). Furthermore, on a five-point scale (“strongly agree, somewhat agree, somewhat disagree, strongly disagree”), we asked participants to evaluate whether the workshop and facilitators were clear, promoted learning, and respected them. Lastly, we asked for them to list their key takeaways from the training in an open-ended question.

All participants reported learning as much as or more than they expected. The majority (91%) strongly agreed that the workshop was well-structured while 64% somewhat agreed that the workshop was intellectually challenging (27% strongly agreed). For the facilitators, 64% of the participants strongly agreed that they gave clear presentations and conducted activities that promoted learning. In addition, all of the participants strongly agreed that they felt respected by the facilitators.

As for the key takeaways, most of participants highlighted that they learned how to create measurable and specific learning objectives, support student learning by integrating student voices, and apply creative assessments to measure learning. Lastly, many of our participants felt motivated to start planning their programs and highlighted how having a framework was a good starting point for them to focus on student learning. This suggests that building advisers’ confidence as educators and providing a general foundation of educational theory for staff members could be an effective first step in enhancing student learning in CCL contexts.

We checked back in with our workshop participants approximately four months after the workshop, with a short, three question pulse survey. Our goal was to find out if and how our participants were applying what they had learned in the “We Are All Educators” workshop. All of the attendees who provided feedback told us that the workshop had helped them infuse new strategies into their programs and projects that support student learning. They have been able to reflect more critically about their projects and programs and revise their materials to be more in alignment with program and learning goals. One participant even noted a benefit of having reduced the need for additional follow-ups with students after incorporating these new approaches. Finally, another participant reported adapting part of the workshop materials for a staff development retreat. She said:

Most [of] our work focuses on program outcomes but we rarely get to focus on aligning those outcomes with student learning and growth–rather than job duties/tasks. I hope this will make for a richer experience for both the student-facing staff and the student staff. We’ve also adapted this for a graduate student/professional student audience because some of the curriculum didn’t quite fit. Still, it translates very well!

While we only received four responses to our follow-up survey, the responses we did receive helped reinforce that we were able to realize the goal of the workshop to increase staff members’ confidence and have real impact in supporting student learning in sustainability-focused CCL activities at Harvard.

Conclusion

Co-curricular learning provides an opportunity for universities to enhance student learning by giving them the experience to apply their knowledge in real-world settings and develop 21st century skills. However, in order for this learning to be fully realized, we believe it is essential that staff members, even if they may not have formal teaching roles at the institution, have the confidence and skills to guide student learning. As elaborated in our theory of change, we argued that staff members must have foundational training in relevant educational theories and best practices to support CCL. As a result, we created the “We Are All Educators” workshop for Harvard staff members who work with students on co-curricular sustainability projects. From our pre-workshop module and our two-part live, online workshop, our participants reported an increase in their level of confidence in creating learning objectives and assessments, supporting student learning, and giving students effective feedback. Our feedback from participants four months after the workshop indicated that at least some of them continued to reflect and apply what they learned in their work with students.

While most of our participants have worked with students on sustainability-related projects and programs, the implications of our workshops can apply to other types of programs and other universities as they strive to enhance student learning in the CCL context. Based on our experience in developing the “We Are All Educators” workshop for sustainability professionals at Harvard, the feedback from our participants, and the literature we reviewed, we offer the following key takeaways from this case study:

- Students find tremendous value in learning through CCL (Briggs et al., 2019; Gramatakos & Lavau, 2019). As such, investments in professional development for non-teaching staff members who support CCL can help facilitate student learning (Barth & Rieckmann, 2012).

- Training staff members to begin incorporating learning objectives, assessments, support strategies, and feedback in CCL can be done in a scalable fashion. We were able to use a blended but fully online learning model, creating an asynchronous pre-workshop module and synchronous remote workshop.

- When developing a training program tailored to a specific university’s environment, documentation is important in order to scale the program across the institution. For example, while we started with the Office for Sustainability, we created a toolkit with all our resources so that the training could be expanded into other departments.

- Increasing staff confidence with general knowledge about learning and educational theories is an important first step to supporting them in enhancing student learning in CCL. Universities should not overwhelm staff members with too much educational theory and training, but rather provide them a foundation to be more confident as educators, a confidence that may grow as they gain more experience.

Four months after our workshop, several of our participants reported continued reflections on their own learning and the importance of working with students to create meaningful, feasible, specific, and student-centered learning objectives for sustainability-related CCL projects at Harvard. In presenting this case study, we hope that sustainability educators and higher education administrators will consider all their stakeholders, especially non-teaching staff members, as potential educators, in order to provide the best learning environment for students. Indeed, “We Are All Educators.”

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by a Spark grant from the Harvard Initiative for Learning and Teaching. The authors also wish to thank Becca Miller of the Harvard Graduate School of Education for her guidance and advice during our workshop development and her helpful comments on a draft of this manuscript.

References

Andersen, A. S. (2016). The Roskilde Model: Problem-oriented learning and project work. Springer.

Barth, M., Godemann, J., Rieckmann, M., Stoltenberg, U. (2007). Developing key competencies for sustainable development in higher education. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 8(4), 416–430. https://doi.org/10.1108/14676370710823582

Barth, M. and Rieckmann, M. (2012), Academic staff development as a catalyst for curriculum change towards education for sustainable development: an output perspective. Journal of Cleaner Production, 26(1), 28-36. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2011.12.011

Blumenfeld, P. C., Kempler, T. M., & Krajcik, J. S. (2006). Motivation and cognitive engagement in learning environments. In R. K. Sawyer (Ed.), The Cambridge handbook of the learning sciences (pp. 475-488). Cambridge University Press.

Briggs, S. J., Robinson, Z. P., Hadley, R. L., & Pederson, R. L. (2019). The importance of university, students and students’ union partnerships in student-led projects. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 20(8), 1467-6370. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSHE-01-2019-0050

Ernst, J., Burgess, E., Erickson, D., & Feldbrugge, R. (2020). Beyond traditional teacher professional development: Innovations in teacher professional learning in environmental and sustainability education. Journal of Sustainability Education, 24.

Everett, J. W., Riddell, W., T., Moore, C., Valentine, S., & Krchnavek, R. R. (2018). Client-oriented project based learning using building audits. Journal of Sustainability Education, 19.

Gramatakos, A. L., & Lavau, S. (2019). Informal learning for sustainability in higher education institutions. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 20(2), 378-392. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSHE-10-2018-0177

Hayles, C. S. (2019). INSPIRE sustainability internships: Promoting campus greening initiatives through student participation. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 20(3), 452-469. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSHE-03-2019-0111

Kolb, A. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Prentice-Hall.

Kwon, R., Brint, S., Curwin, K., & Cantwell, A. (2020) Co-curricular learning at research universities: Results from the SERU Survey. Journal of Student Affairs Research and Practice, 57(1), 90-112. https://doi.org/10.1080/19496591.2019.1644118

Lee, J., Blackwell, S., Drake, J., & Moran, K. (2014) Taking a leap of faith: Redefining teaching and learning in higher education through project-based learning. Interdisciplinary Journal of Problem-Based Learning, 8(2), doi: https://doi.org/10.7771/1541-5015.1426

Lewis, R. A., Kenerson, M. J., Sorrentino, C., & Rowse, T. H. (2019). Experiencing sustainability education: Insights from a living and learning programme. Journal of Education for Sustainable Development, 13(1), 24–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/0973408219847011

Markman, K.M., Ishii, K., Arnow, H. (2021). Professional development and professional identity: A qualitative assessment of the Art of Teaching program. In S. Baughman, J. Belanger, E. Durnan, E. Edwards, M. Kyrillidou, K. Maidenberg, A. Pappalardo, & M. Strub (Eds.), Proceedings of the 2020–2021 Library Assessment Conference: Building Effective, Sustainable, Practical Assessment. Association of Research Libraries. https://www.libraryassessment.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/213-Markman-Professional-Development.pdf

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2020). Strengthening sustainability programs and curricula at the undergraduate and graduate Levels. The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/25821

National Education Association. (n.d.). Preparing 21st century students for a global society. Retrieved from http://www.nea.org/assets/docs/A-Guide-to-Four-Cs.pdf

Redman, E., Wiek, A., & Redman, A. (2018). Continuing professional development in sustainability education for K-12 teachers: Principles, programme, applications, outlook. Journal of Education for Sustainable Development, 12(1), 59–80. https://doi.org/10.1177/2455133318777182

Sara, R. (2011). Learning from life — Exploring the potential of live projects in higher education. Journal for Education in the Built Environment, 6(2), 8–25. https://doi.org/10.11120/jebe.2011.06020008

Wankel, L.A. & Wankel, C. (2016). Integrating curricular and co-curricular endeavors to enhance student outcomes. Emerald Group Publishing.

Kris M. Markman holds a Ph.D. in Communication Studies from The University of Texas at Austin and currently serves as the Director of Professional Education at the Tufts Clinical and Translational Science Institute and Assistant Professor in the Department of Medicine at the Tufts University School of Medicine. Prior to joining Tufts she was Director of Organizational Learning for the Harvard Library. She has worked in higher education for more than 25 years in teaching, program administration, and curriculum and instructional design.

Kris M. Markman holds a Ph.D. in Communication Studies from The University of Texas at Austin and currently serves as the Director of Professional Education at the Tufts Clinical and Translational Science Institute and Assistant Professor in the Department of Medicine at the Tufts University School of Medicine. Prior to joining Tufts she was Director of Organizational Learning for the Harvard Library. She has worked in higher education for more than 25 years in teaching, program administration, and curriculum and instructional design.  David Havelick holds an ALM in Sustainability and Environmental Management from Harvard Division of Continuing Education. As an Assistant Director in the Harvard University Office for Sustainability, David helps to develop and advance University-wide goals, standards, and commitments that are part of Harvard’s overall sustainability strategy. He works with faculty, students, staff, and senior leaders to translate cutting edge research into practice. He also manages the Office for Sustainability’s Living Lab Program and the Council of Student Sustainability Leaders.

David Havelick holds an ALM in Sustainability and Environmental Management from Harvard Division of Continuing Education. As an Assistant Director in the Harvard University Office for Sustainability, David helps to develop and advance University-wide goals, standards, and commitments that are part of Harvard’s overall sustainability strategy. He works with faculty, students, staff, and senior leaders to translate cutting edge research into practice. He also manages the Office for Sustainability’s Living Lab Program and the Council of Student Sustainability Leaders.  Margaret Wang holds an M.Ed. from Harvard Graduate School of Education and was previously a high school social studies teacher. Currently, she is the co-founder and COO of SubjectToClimate, an education nonprofit connecting K-12 educators to credible, engaging, and unbiased teaching resources about climate change.

Margaret Wang holds an M.Ed. from Harvard Graduate School of Education and was previously a high school social studies teacher. Currently, she is the co-founder and COO of SubjectToClimate, an education nonprofit connecting K-12 educators to credible, engaging, and unbiased teaching resources about climate change.