Conceptions of Sustainability within the Redesigned K-12 Curriculum in British Columbia, Canada: Mapping a disputed terrain

Fallon et al JSE Fall 2017 General PDF

LINK: December 2017 General Issue: Curriculum and Change Table of Contents

Introduction

In the late 1980s, the concept of sustainable development emerged in socio-political rhetoric and began to influence educational policies at international, national, provincial and local levels (World Commission on Environment and Development, 1987; United Nations Conference on Environment and Development, 1992; UN Decade on Education for Sustainability, 2005-2014). The most widely accepted definition of sustainability stems from the Brundtland Report released by the World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED) in 1987. The Report offered the definition that sustainable development is “[D]evelopment that meets the needs of current generations without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” (World Commission on Environment and Development, 1987, p. 43). This excerpt, by far the most quoted part of the Report, appears to be a global normative admonition, extolling some of “us” to actively curtail the daily resource depleting activities that not only stunt the growth of other, less fortunate, human members of the planet, but also compromise future members of the planet. A more equitable approach to development, the definition suggests, would limit global mismanagement, both currently and cross-generationally, by accounting for the replacement costs of resource extraction. This definition and its underlying assumptions have produced an impressive scholarly, political, and public discourse around the concept of sustainable development, to the point where it has been replaced with sustainability to remedy the fact that, for some, sustainable development reinforced the inequitable generation and distribution of monetary wealth, while billions of people continue to be impoverished, and ecosystems and resources are being depleted. Luke (2005, p. 233), for example, calls sustainable development both a “social movement for greater commodification” and “[A] rhetoric [that] can be rolled out as a development strategy.” Sustainability as a replacement term is generally defined as an attempt to reconcile economic, environmental, and social systems. The three circles overlap in the middle to show that achieving sustainability necessitates equal measures of market-based innovation, enlightened governance and transformed individual behaviour. The economic circle suggests that the current market system can drive technical innovations that make nature more resilient. The environmental circle suggests that sustainability can be achieved through a restructuring of government, laws and/or educational systems to reflect a managerial focus on a vulnerable natural world. The economic system is a placeholder for sustainable development and so continues to be one strain in the sustainability discourse (Hannigan, 2006), asserting that economic development is compatible with progress on environmental issues, thereby infusing the contemporary discourse of sustainability with neoliberal tenets (McCarthy & Prudham, 2004). Others have removed the development (i.e., economic) part of the phrase. The result is “a broader view of a solution to world needs than was previously provided” (Reid and Petocz 2006, p. 106). Lélé and Norgaard (1996, p. 87), for instance, define sustainability simply as ‘‘the ability to maintain something undiminished over some time period.” Marcuse (1998), approaching continuity over time from a different angle, asserts that sustainability is a constraint on the creation of global poverty—which is sustainable, but undesirable.

An arguably more sophisticated and post-structuralist interpretation of sustainability emphasizes both perspective and context. This approach is a departure from the search for a universal interpretation of the term “sustainability.” Its emphasis is on “how the term works” (Gough, 2006), that is, the ways in which one definition, as opposed to another, best serves the needs of, in the case of Gough’s study, K-12 curriculum developers. This is not to say that any one way of seeing things is as good as any other; instead, it raises the question of how one might argue for one definition over another, based on its better serving the needs of those invoking the definition. Evaluating any definition is, by this post-structuralist reckoning, a listing of its pros and cons in relation to the context in which it is applied.

The purpose of this paper is not to provide a definite conclusion about which conception(s) of sustainability should frame the purposes and practices of education for sustainability, especially in the recent transformation of curriculum policy for the K-12 school system in B.C. The authors aim at providing a critical discussion of various views of society-nature relationships embedded in different socio-cultural paradigms that might be used by curriculum writers as foundations for the construction of a notion of sustainability deemed responsive to a challenging world in terms of sustainable future (Barratt Hacking et al, 2007). We do this by, first, outlining the key features of the diverse sociocultural paradigms that underlie the different conceptions of sustainability that frame educational responses (curriculum) to environmental challenges faced by communities. Second, we address the following key questions: in what socio-cultural paradigm is the dominant conception of sustainability grounded in the New BC Ed. Plan and in which ways does that paradigmatic conception question the dominant industrial notion of modernity and development? For the purpose of this paper, socio-cultural paradigms are defined as background assumptions that offer a way of organizing our perception and understanding of the world and of our political, social, cultural, economic, environmental and educational actions (Bertrand & Valois, 1992).

Environmental Education and Education for Sustainable Development?

Schoenfeld first coined the term environmental education (EE) in 1968 (Hammond, 1998) and its purpose was later on defined by Stapp in these terms: “Environmental education is aimed at producing a citizenry that is knowledgeable concerning the biophysical environment and its associated problems, aware of how to help solve these problems, and motivated to work toward their solutions” (Stapp, 1969, p. 34). The work of Stapp was central in the elaboration of an international framework that provided the role, objectives, and characteristics of EE. His framework was presented in 1977 at the first Intergovernmental Conference on EE as The Tbilisi Declaration (UNESCO, 1978). The document stated: “The ultimate aim of environmental education is to enable people to understand the complexities of the environment and the need for nations to adapt their activities and pursue their development in ways which are harmonious with the environment” (UNESCO 1978, p. 12). According to Hungerford, Peyton & Wilke (1980), the Tbilisi Declaration went on to influence environmental education for 20 years via the principles of ecological foundations, a conceptual awareness of and evaluation of issues and, the training in and application of citizenship action skills. These goals highlight the emerging prevalence of the social side of environmental concerns, proposing lifelong, interdisciplinary learning that focuses on both local and global issues now and in the future. A generation of important efforts focused on individual environmental behaviour change gave rise to the current recognition that raising awareness is insufficient, but it was an important shift in the 1980’s.

Growing international tensions between those who were pro-development – viewing nature as a resource to be exploited with scientific and economic efficiency – and those who were concerned about the ensuing environmental consequences resulted in the previously mentioned Brundtland Commission. The Report asserted that education on the environment “should run throughout the other disciplines of the formal education curriculum at all levels- to foster a sense of responsibility for the state of the environment and to teach students how to monitor, protect, and improve it” (World Commission on Environment and Development, 1987, p. 113). In this way sustainable development resulted in the creation of the concept of education for sustainable development (ESD) and it was defined as “education that allows learners to acquire the skills, capacities, values and knowledge required to ensure sustainable development” (UNESCO, 2006, p. 1).

The emergence of ESD has, among other things, reflected the invocation of a variety of concepts (e.g., eco-literacy, place-based education etc) that have peacefully co-existed because they are all largely designed to solve, from an educational perspective, the societal goal of achieving sustainability. However, some education scholars argue that the goals in EE and ESD are similar as they both promote a vision for a more sustainable future (McKeown & Hopkins, 2007). Other educationalists are apprehensive about linking the term sustainable development to education, and, in particular, its implications for the role of education in society. For example, Sauvé (2005; 2006; 2007) argue that because sustainable development is understood as a phenomenon in which the economy, society, and the environment are treated as equal entities, education for sustainable development problematically implies that the economy exists outside the natural limits of the environment. More problematical is the fact that ESD implies that the environment is a storehouse of infinite resources at disposal of the economy or more fundamentally, human needs (Sauvé, 2007). Thus, ESD could be understood as implicit support for on-going exponential growth and development, which reflects the status quo (Sauvé, 2007).

For these reasons, scholars, such as Sauvé (2007) prefer the term environmental education (EE) for its promotion of a broader understanding of the environment than as mere resources for human wellbeing (Note that EE, mostly the word ‘environmental’, can be politically charged in some jurisdictions, including BC in recent years). These same educationalists assert that EE implies an interdependent relationship between humans and the environment that goes beyond the resource management focus of education for sustainable development to a stewardship ethic that protects ecosystems and all life forms (Jonas, 1984; Sauvé, 2007). Invoking this socio-cultural paradigm for human-non-human relationship, EE challenges the assumptions of a growth economy and directs learners toward the creation of alternate models of progress where economic and social limits are emphasized to help humans co-exist with nature by living within the carrying capacity of the environment (Daly, 2009). To summarize, both EE and ESD suggest the other excludes certain economic models or ways of living in the world based on the belief systems about the political and economic nature of society.

The British Columbian Education Scene

In 1971, in reaction to Stapp’s work (1969) on the concept of EE, a group of local educators requested that the British Columbia Teachers’ Federation (BCTF) set up a Task Force on EE. The Task Force consisted of teachers, principals, university representatives, and superintendents, and its purpose was twofold. First, the Task Force was to define, promote, and advocate for EE and its objectives in BC. Second, its mandate was also to develop and provide relevant learning resources to BC teachers (BCTF, 1971; BCTF, 1972). The Task Force suggested EE programs be interdisciplinary, be developmental throughout K-12, and involve the whole community (BCTF, 1971; BCTF, 1972).

In 1991, the BC Environmental Educators Provincial Specialists Association (EEPSA) prepared a special report entitled “Environmental education in British Columbia,” which reviewed EE content of BC curricula and made recommendations. The suggestions included the need for “a province wide curriculum assessment guide…to allow teachers to develop exciting programs that integrate goals of several subject areas” (BCTF, 1991, p. 44). In 1995, BC’s first provincial interdisciplinary framework for EE-related curricula was published. Entitled “Environmental Concepts in the Classroom (ECC)”, it would become BC’s first EE framework. ECC was developed and published to “assist teachers in all subjects and grades to integrate environmental concepts into their daily lesson plans” (BC Ministry of Education, 1995, p. 3). In this document, six guiding principles were formulated for integrating EE into the classroom:

1.direct experience with the environment (i.e., providing opportunities for students to explore the natural world and gain an understanding of natural systems)

2. responsible actions (i.e., learning how to act responsibly and the consequences of actions)

3. understanding of complex systems that sustain life (i.e., a consideration of the interrelatedness of natural systems, and how human activities impact these systems)

4. consequences of human decisions and actions (made at individual, local, national, and international levels)

5. aesthetic appreciation of the environment (i.e., valuing and respecting nature through visual, physical, emotional, and other connections)

6. environmental ethics (i.e., providing opportunities for students to question cultural assumptions that lead to social conflict and environmental crises) (BC Ministry of Education, 1995).

In terms of practical implementation, ECC was a “supplementary curriculum resource” and, as such, was not mandatory for teachers to enact in their practice. The process that created the ECC did not include funding and other resources for the important work of integrating the framework into the mandatory K-12 curricula, nor were focused professional development and other key implementation strategies undertaken. That said, all mandatory subject area curricula at the time (Integrated Resource Packages or IRPs) did include an Appendix C, which promoted the practice of “cross-curricular connections” (of which “the environment” was identified as a key cross-curricular organizer) and pointed educators to the ECC document.

In 2007, the 1995 EEC document was revisited and, through a provincial consultation process taking into account national and international developments in the environmental education field, a new framework for “environmental learning” in B.C. was developed. Entitled “Environmental Learning and Experience (ELE): An Interdisciplinary Guide for Teachers,” this document was informed by advances in EE research as well as the Kyoto Protocol, Montreal and Johannesburg Summits on Sustainable Development, and the proclamation of the United Nations Decade of Education for Sustainable Development (UNDESD) from 2005-2014 (BC Ministry of Education, 2007). The ECC’s principles for organizing and conceptualizing environmental education were slightly modified, and the six guiding principles were condensed. “Direct experience” was identified as a fundamental pedagogical approach to enacting environmental learning through experiential approaches. That left a framework of more content-oriented principles, including:

1. a consideration of complexity (complex systems)

2. aesthetics (or aesthetic appreciation)

3. responsibility (responsible action and consequences of action)

4. the practice of an environmental ethic

These four principles form a mnemonic, C.A.R.E. (Complexity, Aesthetics, Responsibility and Ethics), as well as a metaphor to describe the treatment needed so that environmental knowledge reflects the interdisciplinary nature of environmental concepts (BC Ministry of Education, 2007).

The ELE Curriculum Guide was endorsed by the BC Ministry of Education and proved to be a relatively popular and useful theoretical framework to guide educators in the practice of environmental and experiential education. Importantly, a network of education partners in B.C. supported the practical implementation through province-wide professional development initiatives, the development of the ELE Curriculum Maps (which mapped the ELE framework across mandatory K-12 curriculum), a set of exemplar videos and a range of other resources to support practice.

Framing the Discussion about Notions of Sustainability

This section of the paper addresses the concept of sociocultural paradigms, which are the accepted ways of knowing, relating, valuing, and acting in a society. For our purposes, these assumptions inform the nature of sustainability and the accepted practices of individuals, groups, or institutions that comprise a society (Bertrand and Valois, 1980; 1992; Gladwin, Kennelly & Krause, 1995; Bonnet, 1999). Bertrand and Valois (1992) offer the following definition of a socio-cultural paradigm:

The action exercised by a society, as a result of its activity, on its social and cultural practices, by the combination of five elements: a concept of knowledge, a concept of relations among persons, society, and nature, a set of values, a way of doing things, and an overarching sense of significance (p. 69).

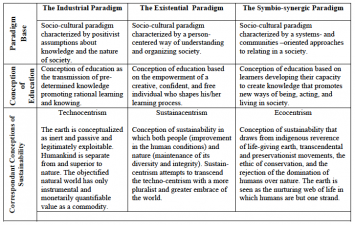

In what follows, we use the key features of the industrial, existentialist, and symbio-synergetic socio-cultural paradigms to illuminate changing conceptions of sustainability as these inform related educational policy and curriculum.

The Industrial Socio-Cultural Paradigm

The industrial paradigm is characterized by positivist assumptions about knowledge and about the relationships among persons, society, and nature (Bertrand and Valois, 1980; 1992; Gladwin, Kennelly & Krause, 1995). In relation to sustainability, positivist assumptions locate humans at the apex of the natural world. These assumptions promote a detached approach to the non-human world, such that it is a storehouse and spectacle for human’s uses and amusements. Within this ontology, the following constructs and practices are valorized: first, the primacy of humans over non-humans; second, the separation of nature and culture; third, the priority of the autonomous individual over community well-being; fourth, belief in objective knowledge, reason, and science (e.g., data and technology) as the only valid modes of knowing; and, fifth, the cultural construction of the economic system as an independent and self-regulating entity outside of social relations and ecosystems.

Within this paradigmatic understanding of the world and society, the earth is conceptualized as inert and passive and legitimately exploitable. The objectified natural world has only instrumental and monetarily quantifiable value as a commodity within a free-market ideology, which subordinates human activity and the sustainability of the environment to the laws of the market (Escobar, 2010). It exclusive reliance on markets for natural resource allocation overlooks the concerns of nature, and some of marginalized segments of society including women and minorities, and the interest of future generations. This understanding of sustainability is referred to as techno-centrism which is based on the disassociation of the human economy from non-human nature. It disregards scientific understandings regarding resource availability, the biophysical interdependence between human and natural worlds, and the finite materially closed character of the global. In all, the “environment as a resource to be developed and managed; rational use of resources for sustainable profit and thus sustainable quality of life” (Sauvé, 1996, p. 27).

Educationally speaking, the industrial paradigm frames education on the environment within a rational and techno-centric realm (Bertrand & Valois, 1992; Sauvé, 1996). The cultural aim of this educational paradigm is largely to initiate students to the idea of progress and well-being through consumption, and to foster a vision of creativity as synonymous with economic, scientific, and technological progress. Consistent with this aim, education present human relations in terms of, and ultimately subservient to, economic relations, and foster the image of the desirable individual as one who is “opportunist, materialist, and conformist” (Bertrand & Valois, 1980, p. 173). Politically, education should “contribute to maintaining a hierarchical social structure [and] acceptance that an [elite] minority make [and furthermore should make] decisions on behalf of the majority” (ibid, p. 173). In terms of the socio-economic order, such education “relativizes the importance of the student as a person and a critical citizen evolving in a democracy whilst maximising her importance as a future worker” (ibid, p, 173). It “promotes intellectual aptitudes, contributes to reproducing the [existing] social divisions in work, and promotes the legitimacy of the established order and its values” (ibid, p. 173). Furthermore, the socio-economic role of this educational paradigm is “to reflect an apparent neutrality by abstaining from all normative critique; to promote method and efficiency, control and the economy; and to transmit a ‘mecanomorphic’ image of the person” (p. 199). The overarching function of education is its contribution to maintaining the status quo, especially with regard to conceptual and practical ways of understanding the notion of sustainability.

The Existential Paradigm

The existentialist paradigm (paradigm centered on the person) is different from the industrial paradigm on just about every criterion that matters. Knowledge is a matter of interaction, not subject-object separation as in the industrial paradigm; knowledge is subjective and existential. Knowledge is produced by suppressing “reductionisms” and by the quest to understand relations, by the “systematization” of subjective experience. Science is not neutral as “all experiences, intuitive, mystic, religious, and psychic can be meaningfully integrated” (Bertrand & Valois, 1992, p. 225). With regard to relations among persons, society, and nature, the existential paradigm, according to Bertrand and Valois, offers an essentially teleological concept of life and evolution. The world is a system of relationships between means and ends. The ultimate purpose of society is neither scientific nor economic but rather to facilitate development of all the potentialities of the person so that (s)he becomes a “fully functioning” person. Society and groups within it are but means to that end. Such an end may require some domination of the person over her biophysical, social, and cultural milieu.

In terms of conception of sustainability, the existentialist paradigm offers a vision, which is both people-centered (concentrating on improvement in the human conditions) and conservation-based (maintaining the variety and integrity of nonhuman nature). This vision is referred to as sustain-centrism (Gladwin, Kennelly & Krause, 1995; Bonnet, 1999). Greater balance is sought within the 3E triad of sustainable development: economy, ecology, and ethics. Whereas the industrial paradigm and techno-centric view of sustainability are biased toward the economy and market-based rights, a sustain-centric conception of sustainability attempts to transcend the former with a more pluralist and greater embrace of the world. Basically, sustain-centrism is inspired by ideals such as the universalism of life, the rejection of the concept of human stewardship over the Earth, ecological economics (e.g., environmental services), conservation and resource management, and the complexity of nature (Gladwin, Kennelly & Krause, 1995).

The education approach in a sustain-centric conception of sustainability emphasizes humanism (Bertrand & Valois, 1980; 1992), the development of individuals into persons who are comfortable with themselves and “function” fully while advocating human values that call for a healthy ecological, social, and economic context (Gladwin, Kennelly, & Krause, 1995). The epistemological function of education here is to promote a concept of knowledge built on subjectivity and transformed into a quality of being. Knowing in this view of education is not aimed at material accumulation through competition but at being, at the organic integration of one’s various achievements in balance with the environment. The cultural function of an humanist education is, for Bertrand and Valois, to promote subjective creativity as the model of creativity, to promote self-expression, communication, joy, and love, “to propose a ‘new’ image of the person within which the person is internally free to move in any direction” and to choose freely how to be a “changing process” in order to live fully in balance with its natural environment, to be open to experience oriented toward the present moment, a creative person, confident in her being, and possessing a sentiment of total liberty (p. 245). Politically such education criticises the manner in which a democratic society treats individuals and works to restore power to the individual. Socio-economically humanist education leads the dominant social order to center on the person. Thus, humanist education critiques authoritarian structures. Depending on context (how existentially focused a society is at the moment one is considering it, for instance), humanistic education might lead in one of three global directions: maintenance of the status quo, maintenance of the existing order coupled with efforts to reshape it into a more “human” character, or creation of a new society centered on the person in balance with the environment (where a society, for instance, is currently largely focused on economic efficiency). Thus, unlike the educational paradigms associated with the industrial socio-cultural paradigm, humanistic education adjusts its principal “function” to its context (p. 245).

The Symbio-Synergetic Paradigm

A challenger paradigm has emerged to imagine a post-industrial and post techno-centric era and it is called the symbio-synergetic paradigm. As described by Bertrand and Valois (1980; 1992; Gladwin, Kennelly & Krause, 1995; Sauvé, 1995), this paradigm is focused on a symbiotic mode of knowing, which unifies “subject” and “object,” and promote relational ontologies that conflates nature and culture, us and them, individual and community. The symbio-synergetic paradigm recognizes the “metaphorical” character of all concepts and accepts different ways of knowing (Escobar, 2004, p. 212). It embraces complexity rather than seeking the deceptive reassurance of binaries. With respect to relationships, opposition among persons, society, and nature is minimized in a comprehensive eco-system where” [A]ll forms of knowledge can contribute in different and complementary ways to “communities and projects.” With regard to the technical and practical aspects of existence, this paradigm promotes “counter-technology” and “soft technology,” such as “renewable resources” as opposed to a “hypertechnification of rationality and hyper-marketization of social life (Escobar, 2004, p. 209; ibid, p. 223).

The way that sustainability is being conceptualized here draws philosophical inspiration from the critical order of nature, indigenous reverence of life-giving earth, transcendental and preservationist movements, the land ethic of conservation, and the deep ecology movement that rejects the domination of humans over nature. This conceptual and practical understanding the notion of sustainability is called eco-centrism (Gladwin, Kennelly & Krause, 1995). Epistemologically speaking, symbio-synergetic assumptions contest the viewing of nature as an “object” to be “exploited” by humans who are entitled to the spoils of their superiority (Denis, 1997, p. 133-134). The earth is seen as the nurturing mother of life, a great interlocking order, and a web of life in which humans are but one strand. Humans are both ontologically and phylogenetically unseparated from the rest of nature. Nonhuman nature should not be used only to satisfy vital needs of sustenance. Ethical priority is given to the whole over parts – a decision is considered ethical if it preserve the integrity, stability, and beauty of the biotic community.

The education approach in modelling the eco-centric conception of sustainability occurs in what is called the inventive educational paradigm (Bertrand & Valois, 1980, 1992), which refers to a community-led process of critical investigation toward the transformation of social realities in relation to sustainability challenges being faced by communities (Sauvé, 1996). The general function of the inventive paradigm, as explained by Bertrand & Valois (1980, 1992), is to develop the capacity for social invention and for creation of new social institutions. Education situated within the inventive paradigm also seeks to nurture the capacity of learners of inventing future situations and intervention modes capable of bringing about such new social institutions and solutions to sustainability challenges. The inventive educational paradigm promotes a symbiotic mode of knowing that takes as its starting point the essential union of observer and observed. Following this starting point, the educational paradigm is inventive as it aims at enabling learners to bringing about new social institutions and the reconceptualization of the concept of sustainability. Culturally, the inventive paradigm promotes an educational focus on diversity, equality, co-creation and consensus. Education constituted within inventive principles should “resituate personal development within community development and community development within personal development” (Sauvé, 1996). In short, inventive education should promote diversified forms of participation in the symbio-synergy of the human and environmental world as a whole. The overarching function of such education is to contribute to the recognition of differences of worldviews and of the complementarity of those differences within a fundamental union of persons with each other and with the entire environment (harmony and balance of all with all).

Table 1 presents a summary of the different conceptions of sustainability within competing socio-cultural paradigms and their corresponding visions of education. Table 1 demonstrates that notions of sustainability are diverse and contested as they are embodied in competing socio-cultural paradigms. It should be emphasized that all three paradigms have made contributions to curricula over time and these vary according to classroom content and delivery. For example, the industrial view did initiate a recognition of a human relationship to the earth, however objectified this is/was. While acknowledging these contributions, we posit the claim that we need more of the symbio-synergetic socio-cultural paradigm at this time and the new BC Ed Plan is part of a shift towards these values and actions. The basic principle that we are promoting is the idea that the more a community or society adheres to the values of one dominant socio-cultural paradigm as organizational framework for the conduct of its human activities, to the exclusion of others, the greater the danger that the community or society might fail to effectively address the need for more fundamental transformations in ways communities interact with each other and with the natural environment as the basis of sustainability (Loorback, 2007). The next section of our paper draws on this information in a brief but critical review of the conceptions of sustainability as they are embedded in the wording of the new K-12 curriculum in B.C. The intention is to present a thorough analysis of the curriculum, but rather its roots in socio-cultural conceptions of sustainability.

Competing Conceptions of Sustainability in New BC Curriculum Policy

There are numerous principles and guidelines in the renewed BC curriculum that support an enhanced focus on sustainability in K-12 education. According to the Ministry of Education, “educated citizens understand the importance of learning about the environment” (BC Ministry of Education, 2016, np). Speaking to the symbio-synergetic paradigm’s focus on a non-hierarchical mode of interdependent existence, is the fact that sustainability is part of the Personal and Social Core Competency, which means that sustainability is a responsibility that should be infused into every grade and topic. Situating education for sustainability within a curriculum that resonates with a symbio-synergetic social cultural paradigm means that sustainability is linked to the abilities and dispositions that promote the interdependence of people with each other and the natural environment.

As echoed in the work of Santos (2006) and Escobar (2005), we argue that the symbio-synergetic paradigm and its corresponding conception of sustainability provide a space for students and educators in which they could move beyond the industrial paradigm of modernity in two ways: epistemologically and socio-politically. Epistemologically, the symbio-synergetic paradigm and the notion of ecocentrism entail a transition from the dominance of positivist assumptions about what should be considered as valid knowledge to “a plural landscape of knowledge forms” with regard to the concept and practice of sustainability (Escobar, 2004, p. 212, italics added). Socially and politically, the transition is between a hyper-marketization of social life and emergent alternative forms of sustainable livelihoods that assert “a logic of difference and possibility that build on the multiplicity of actors and actions operating at the level of everyday life” (Escobar, 2004, p. 223). Gone are views of nature as an “object” to be “exploited” with scientific efficiency by humans who represent the apex of evolution and are thus entitled to exploit the spoils of their superiority.

In the new BC curriculum, students are expected to “develop awareness and take responsibility for their social, physical, and natural environments by working independently and collaboratively for the benefit of others, communities, and the environment” (BC Ministry of Education, 2015b, np). Notably, this is articulated as the “ability to initiate positive, sustainable change for others and the environment, to analyze complex social or environmental issues from multiple perspectives” (BC Ministry of Education, 2015a). The new BC curriculum also puts strong emphasis on “embedding Aboriginal knowledge and worldviews in authentic and meaningful ways in all areas of learning” (BC Ministry of Education, 2016). In addition, “teachers are encouraged to teach in ways that respect the place in which the students are — to teach from within the school and its surrounding community. Collaboration with community members exemplifies many of the First Peoples Principles of Learning and nurtures cross-generational and relational learning” BC Ministry of Education, 2016. These and other key foundations of the new curriculum in BC indicate a significant shift toward the symbio-synergetic paradigm.

The BC Education Plan is committed to personalize learning for students. This resonates with the symbio-synergetic paradigm’s desire to integrate individuals, classroom learning and communities. As the BC Ed Plan BC Ministry of Education, 2015a) focuses also on the need to create more opportunities for students to apply their knowledge in real-world settings, outside the bounds of a traditional classroom – and this requires new and renewed community partnerships. The paradigmatic backdrop to the new BC curriculum is a mosaic, a bricolage of conceptions of reality. These don’t necessarily spell unmanageable contradictions; they are evidence of the existence of different socio-cultural paradigms over time. Mixed with acknowledgements of the need for students to engage the real-world, are seeming throwbacks to the industrial paradigm in the form of the language of competencies, which are also key to the new BC curriculum. It is asserted that K-12 student development is predicated on acquiring “intellectual, personal, and social and emotional proficiencies that all students need to develop in order to engage in deep learning and life-long learning” (BC Ministry of Education, 2015a, p.6). Having acknowledged the rationalist roots of these proficiencies or competencies, the sustainability-related skills themselves include systems thinking and a positive orientation to analyzing change; all of which mirror the symbio-synergetic paradigm.

To put this quote in (symbio-synergetic) socio-cultural terms, a relational ontology is present that promotes an exploration of the individual-community connections in our human systems. Drawing out and implementing these connections necessitates capacity building; especially among teachers who will need to partake of professional development activities and networking events in order to create solid partnerships among the increased number of community-based educational partners being called for. Furthermore, the teacher is being asked to co-design classrooms for democratic problem solving.

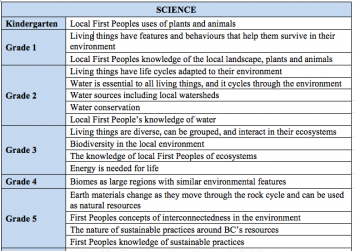

As Table 2 demonstrates, a relational ontology undergirds the new BC Science curriculum. Importantly, the Science curriculum takes a place-based approach to learning, where students “develop place-based knowledge about the area in which they live, learning about and building on First Peoples knowledge and other traditional knowledge of the area. This provides a basis for an intuitive relationship with and respect for the natural world; connections to their ecosystem and community; and a sense of relatedness that encourages lifelong harmony with nature” (BC Ministry of Education, 2016). As mentioned, the First Peoples Principles of Learning (FPPOL) is a core foundation of the renewed BC curriculum. FPPOL is beyond the scope of this paper, but we will extend this point in an in-depth analysis for a future publication. As Table 2 highlights, alerting students to the importance of traditional knowledge begins in Kindergarten and extend through to Grade 12 in the new BC Science curriculum.

Table 2 (partial): Selected Learning Standards aligned with a focus on Sustainability in K-7 Curriculum

Table 2 provides a snapshot of selected learning standards that emphasize a relational ontology as a core curricular focus in Science and Social Studies. The curriculum in Science and Social Studies promotes approaches to teaching and learning strategies that emphasize hands-on, community-connected and real-world, learning experiences. A wide range of such sustainability-related activities, include examples such as outdoor classroom-based learning, issues-based inquiries, field-based experiences, stewardship activities, or school-based action campaigns. In general, learning would emphasize and demonstrate the importance of cultivating ties to community while simultaneously gaining an awareness and appreciation of the natural world.

Relatedly, place-based learning is another key concept that can be detected in Table 2 and which flows from a symbio-synergetic paradigm. It is a cross-curricular instructional approach that emphasizes the value of learning directly from one’s own community or region, and is keenly aligned with approaches to sustainability that aim to develop an active, engaged, and educated citizenry. In the new Science curriculum, for example, there is a strong progression of mandatory learning standards that are grounded in an exploration of place, ecology and sustainability from K to 12. Indeed, it is now mandatory that students “experience and interpret the local environment” and “express and reflect on personal experiences of place” (Ministry of Education, 2016).

Aligned with the symbio-synergetic paradigm, students now explore ecological principles, relationships and interconnectedness throughout the elementary years in Science, focus on sustainable resources and practices in the intermediate grades, and inquire about sustainable systems and practices in the secondary years. Importantly, this progression of learning with sustainability as a core focus is weaved together with First Peoples knowledge, perspectives and principles of learning throughout student’s K-12 experiences.

Conclusion

Our original intent was to identify and discuss diverse socio-cultural paradigms that may be having emerging influences in the conception of sustainability in BC education. This paper demonstrates that the symbio-synergetic paradigm and its emphasis on relationships and place reflect highly prioritized social values that appear to significantly impact the renewed BC curriculum with regard to sustainability. For example, BC teachers can now look to the K-12 curriculum and see that sustainability is aligned with the core competency of social responsibility, which promotes educational concepts like life-long learning, place-based learning, and the First Peoples Principles of Learning. Sustainability and related concepts also have stronger foundations in specific subject-area curricula and learning standards, most notably in Science and Social Studies, and as a cross-curricular thematic priority.

So what views of society-nature relationships are being advocated? To us, sustainability is not a standard as much as a metaphor, a shorthand descriptor for multi-faceted narratives that attempts to coalesce a number of issues and social movements under a single concept for the purposes of dialogue and resolution. The usual issues of international development, environmental degradation and economic well-being are present, but so are notions of ethics, rights, responsibilities, knowledges, and community(ies). Perhaps because sustainability is a long-term challenge, there appears to be a willingness to engage in smaller-scale, local efforts. It is more speculative to suggest this but social institutions, including education, appear to be coming to terms with the need to interact on solutions as opposed to vying for dominance or abdicating responsibility. The symbio-synergetic paradigm appears to be providing the socio-cultural basis for the continued development of education for sustainability in BC.

Moving forward, we hope to see an openness to multiple paradigmatic perspectives as we continue to develop curriculum, while articulating and exemplifying the necessary competencies, skills and abilities for anticipating the future of education in BC including a major rethinking of pedagogical practices. Clearly, the symbio-synergetic paradigm can support this transformation of practice as well, toward more collaborative learning and knowledge construction, joint-analysis and dialogue, co-planning, enacted learning, and non-hierarchical control of place-based decisions and outcomes. As the classroom extends outwards to include the unique and invaluable experiences of place and community, we recall here its emergence from a structured and efficient transmission of pre-determined knowledge. Like many in the sustainability community we are working to promote the re-casting of the ideas of progress and well-being in relation to sustainability. Starting with the values and actions that attend such goals, we anticipate (with considerable excitement) the timely opportunity to transform our educational practices in alignment with our new curriculum in BC.

References

Barratt Hacking, E., Barratt, R. & Scott, W. (2007). Engaging children: research issues around participation and environmental learning. Environmental Education Research, 13(4), 529-544, DOI: 10.1080/13504620701600271.

Bertrand, Y. and Valois, P. (1980). Les options en éducation. Québec: Ministère de l’Éducation. Bertrand, Y. & Valois, P. (1992). École et sociétés. Montréal: Éditions Agence d’Arc.

Bonnett, M. (1999). Education for sustainable development: A coherent philosophy for

environmental education? Cambridge Journal of Education, 29:3, 313–324.

B.C. Ministry of Education. (1995). Curriculum framework and the environmental concepts in the classroom: A guide for teachers. Victoria: Ministry of Education.

B.C. Ministry of Education. (2007). Curriculum framework and the environmental concepts in the classroom: A guide for teachers. Victoria: Ministry of Education. Retrieved from: http://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/education/kindergarten-to-grade-12/teach/teaching-tools/environmental-learning/environ_learning_exper.pdf

B.C. Ministry of Education. (2015a). BC Education Plan. Victoria: Ministry of Education.

Retrieved from: http://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/education/kindergarten-to-grade-12/support/bcedplan/bcs_education_plan.pdf

B.C. Ministry of Education. (2015b). Social Responsibility Competency Profiles. Victoria:

Ministry of Education. Retrieved from:

https://curriculum.gov.bc.ca/sites/curriculum.gov.bc.ca/files/pdf/SocialResponsibilityCompetencyProfiles.pdf.

B.C. Ministry of Education. (2016). Science K-9 Curriculum. Retrieved from:

https://curriculum.gov.bc.ca/curriculum/science/goals-and-rationale

B.C. Ministry of Education. (2016). K-9 Curriculum: Curriculum Overview. Retrieved from: https://curriculum.gov.bc.ca/curriculum/overview

British Columbia Teacher’s Federation (BCTF). (1971). Report of meeting task force on

environmental education. Report prepared by the Division of Professional Development. Vancouver, BC.

British Columbia Teacher’s Federation (BCTF). (1972). Environmental education…why? Report prepared by the Division of Professional Development. Vancouver, BC.

British Columbia Teacher’s Federation (BCTF). (1991). Environmental education in British Columbia. Report prepared by the Environmental Educators Provincial Specialist

Association. Vancouver, BC.

Daly, G.C. (2009). Ecosystem services in decision making: time to deliver, Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 7(1), 21−28.

Denis, C. (1997), We Are Not You: First Nations and Canadian Modernity, Broadview Press, Peterborough, ON.

Escobar, A. (2004), Beyond the Third World: imperial globality, global coloniality and antiglobalisation social movements, Third World Quarterly, 25(1), 207−230.

Escobar, A. (2010), Latin-America at a crossroad: alternative modernizations, post-liberalism, or post-development? Cultural Studies, 24(1), 1−65.

Gladwin, T., Kennelly, T. & Krause, S., (1995). Shifting paradigms for sustainable

development: Implications for management theory and research, The Academy of Management Review, 20(4), 874–907.

Gough, N. (2006). Lost children: Anxieties in Australian education. Journal of Curriculum and Pedagogy, 3 (2), 63-67.

Hammond, W.F. (1998)). The earth as a problem: A curriculum inquiry into the nature of

environmental education. Master Thesis, Simon Fraser University. Retrieved from:

http://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/obj/s4/f2/dsk2/tape17/PQDD_0024/NQ37710.pdf

Hannigan, J. (2006). Environmental sociology: A social constructionist perspective

(2nd ed.). New York: Routledge.

Hungerford. H., Peyton, R.B. & Wilke, R.J. (1978). Goals for curriculum in environmental

education, The Journal of Environmental Education, 11(3), 45−58.

Jonas, H. (1984). The Imperative of Responsibility: In Search of an Ethics for the Technological Age. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Loorbach, D. (2007). Transition management: New mode of Governance for sustainable

development. Utrecht: International Books.

Lélé, S. & Norgaard, R.B. (1996). Practicing interdisciplinary, Biosciences, 55(11), 967−975.

Luke, T. W. (2005). Neither sustainable nor development: reconsidering sustainability in

development, Sustainable Development, 13: 228–238. doi:10.1002/sd.284

Marcuse, P. (1998). Sustainability is not enough, Environment and Urbanization, 10(2),

103−111.

McCarthy, J. & Prudham, S. (2004). Neoliberal nature and the nature of neoliberalism,

Geoforum, 35, 275−283.

McKeown, R., & Hopkins, C. (2007). International Network of Teacher Education Institutions: Past, present and future, Journal of Education for Teaching, 33(2), 149-155.

Reid, A. & Petocz, P. (2006). University lecturers’ understanding of sustainability, Higher

Education, 51: 105–123.

Santos, B.D.S. (2006). The Rise of the Global Left: The World Social Forum and Beyond, Zed Books, New York, NY.

Sauvé, L. (1996). Environmental education and sustainable development: Further appraisal. Canadian Journal of Environmental Education, 1(1), 1–30.

Sauvé, L. (1999). Environmental education between modernity and postmodernity: Searching for an integrating educational framework. Canadian Journal of Environmental Education, 4(1), 9–35.

Sauvé, L. (2005). Currents in environmental education—Mapping a complex and evolving

pedagogical field. The Canadian Journal of Environmental Education, 10, 11–37.

Sauvé, L. (2006). L’organisation et la structuration du secteur de l’éducation en réponse au programme onusien du développement durable. Liaison Énergie-Francophonie, 72, 33–41.

Sauvé, L. (2007). La dérive et l’impasse du développement durable. In S. Mongeau, (Ed.),

Objecteurs de croissance (pp. 33–57). Montréal, Canada: Éditions Écosociété.

Schuftan, C. (2003). The emerging sustainable development paradigm: a global forum on the cutting edge of progressive thinking. The Fletcher Journal of International Development, XVIII, 73–78.

Sharpley, R. (2000) Tourism and sustainable development: Exploring the theoretical divide, Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 8(1), 1–19.

Stapp, W.B. (1969). The concept of environmental education, Environmental Education, 1(1), 30−46.

United Nations, (1992). United Nations Conference on Environment & Development. Retrieved

from: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/Agenda21.pdf

UNESCO, (1978). Intergovernmental Conference on Environmental Education: Final Report. Retrieved from: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0003/000327/032763eo.pdf

UNESCO, (2005). UN Decade of Education for Sustainable Development: 2005 – 2014.

Retrieved from: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0014/001416/141629e.pdf

UNESCO, (2006). Education for sustainable development toolkit: Education for sustainable development in action learning & training tools N°1. Retrieved from:

http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0015/001524/152453eo.pdf

World Commission on Environment and Development, (1987). Our Common Future. Oxford University Press, Oxford/New York.

Dr. Gerald Fallon PhD - His research focuses on issues of public education with specific threads related to education law, policy, sustainability, leadership, and community development. He is a member of the Scientific Committee of the Sustainability and Education Policy Network (SEPN).

Dr. Gerald Fallon PhD - His research focuses on issues of public education with specific threads related to education law, policy, sustainability, leadership, and community development. He is a member of the Scientific Committee of the Sustainability and Education Policy Network (SEPN).  Robert VanWynsberghe PhD - His research is rooted in essential questions about human action and social change in the field of sustainability. His main area of research is a pragmatist-inspired study of education for social change.

Robert VanWynsberghe PhD - His research is rooted in essential questions about human action and social change in the field of sustainability. His main area of research is a pragmatist-inspired study of education for social change.  Patrick Robertson – His research focuses on sustainability learning pathways in teacher education. In his consulting work, he engages communities, builds leadership capacity, influences policy, and develops partnerships, programs and resources for K-12 and post-secondary audiences.

Patrick Robertson – His research focuses on sustainability learning pathways in teacher education. In his consulting work, he engages communities, builds leadership capacity, influences policy, and develops partnerships, programs and resources for K-12 and post-secondary audiences.