Climate change communication beyond the ‘ivory tower’: A case study about the development, application and evaluation of a science-education approach to communicate climate change to young people

Link to Deepening Our Craft February 2017 JSE TOC

Link to Deepening Our Craft February 2017 JSE TOC

Riede et al JSE Feb 2017 General Issue PDF

Abstract: The aim of this case study was to develop, apply and evaluate a science-education workshop format to communicate climate change to young people. Based on current theory in climate change communication and Education for Sustainable Development, the workshop has been applied in different contexts with more than 300 children and teenagers. A specification of the consecutive steps should help practitioners to use the workshop in their contexts. While results of the application of the workshop should give an insight into what can be expected from the workshop, an impact assessment of the participants who took place in the workshop outlines the effects it has on students. This paper does not only provide hands-on advice on how theoretical climate change communication knowledge can be translated into action, it also outlines the impacts of the described workshop.

Keywords: Climate Change Communication, Education for Sustainable Development, Moderate-Constructivism, Science Education, Societal Transformation

1. Introduction

Responding to key challenges of the 21st century, such as global climate change, is a complex process of societal transformation. While the body of knowledge on the physical science basis of climate change and its impacts is growing steadily, there is not yet an equivalent understanding of the societal challenges of global climate change and effective measures to react or even “proact” accordingly. However, key policy documents, reaching from the IPCC 5th Assessment Report (Stocker et al., 2013) to the EU Adaptation Strategy (European Commission, 2013a), to climate strategies on national (e.g. Austria, Germany) and regional levels (e.g. Province of Tyrol/Austria) prioritise participatory approaches for knowledge-sharing and capacity development as well as public engagement in general. In this respect, it is vital to follow a transdisciplinary approach, which is applied in a dialogic and target-group oriented format, and thereby enables the development of more effective strategies tackling the complex challenges connected to global climate change (Lange, 2003; Max-Neef, 2005; Mittelstraß, 1987; Muhar & Vilsmaier 2006). Since stakeholder integration and the co-production of knowledge by scientists and stakeholders is especially challenging, Lang et al. (2012) point at the need for experience-based guidelines that build on empirical success (and failure).

Young people play an important role in this process of (societal) transformation. First of all, they are a particularly vulnerable generation as they will be exposed to climate change (impacts) much longer and much more intensively than any generation before. In addition to direct impacts, Fritze et al. (2008) identify health implications of climate change as being: the impact of extreme weather events; the effect of social, economic and environmental disruptions to vulnerable communities; and anxiety regarding the future. Secondly, there is hardly a target-group which is organisationally more accessible than children and teenagers. Despite the fact that this implies an opportunity to “use” them as multipliers to convey a particular message like mitigation into an entire household, it also requires a lot of sensitivity and responsibility. Above all, today’s children and teenagers will be the leading decision makers in the future. Therefore, integrating and engaging them in the climate change debate as early as possible is fundamental for a more sustainable future.

Several larger programmes such as Children in a Changing Climate (CCC) have looked at opportunities for children and teenagers to influence and engage in climate change policy (Mitchell et al., 2009; Walden et al., 2009). A number of scientists have developed an evidence base to empower children and teenagers as change agents within their communities (Haynes et al., 2010; Mitchell et al., 2008; Tanner et al., 2009; Tanner, 2010). According to these findings, engaging children in climate change science and policy is legitimised when their needs as recipients or beneficiaries are fulfilled and/or they are actively engaged in decision-making and planning (Tanner, 2010). In order to help children and teenagers understand, address, mitigate, and adapt to the impacts of climate change, encourage the changes in attitudes and behaviours needed to put our world on a more sustainable development path, and build a new generation of climate change-aware citizens, science education plays a key role (UNSECO, 2010).

Due to a number of alarming reports about students’ science achievements by the US Department of Education at the end of 2008 (e.g. National Center for Education Statistics, 2007), President Obama called for more scientist involvement in education and announced new initiatives for science research and education, challenging scientists to use their knowledge to think about innovative ways to engage young people in science (Nat Neurosci, 2009). In a European context, there are more and more individual scientists who promote aspects of “education and public outreach” in research projects (Illetschko & Taschwer, 2014). Furthermore, this request has been taken into account by the European Commission who launched the “Call for Integrating Society in Science and Innovation” in the research program Horizon 2020 (European Commission, 2013b). The Austrian programme “Sparkling Science”, funded by the Federal Ministry of Science, Research and Economy (BMWFW), which started in 2007, is a role-model that adopts an unconventional way in the promotion of young scientists that is unique in Europe (Sparkling Science, 2014).

Numerous empirical studies have focused on barriers and incentives to the engagement of the public in (climate) science. Despite time constraints and particular demographic factors (Royal Society, 2006) as well as peer attitudes (Poliakoff and Webb, 2007; Royal Society, 2006), scholars claim the need for attractive incentives for scientists to participate in public-engaging efforts (Sisk et al., 2011). However, being really successful in engaging children and teenagers, scientists must also receive profound training and advice to teach and communicate with them (Nat Neurosci, 2009).

Due to the fact that climate change and energy related topics will have increasing impact on every sphere of society, researchers working in this field are regularly confronted with requests to engage the public. Therefore, this article aims at a target group of all disciplines working on the climate change / energy / sustainability “front”. It outlines a communication format that is based on current thinking in climate change and sustainability communication, field-tested and evaluated. Many research activities in science education are characterized as basic research (e.g. research on learning processes) and lack the connection to the reality of the teachers and students’ needs. Other projects can be defined as applied research (e.g. development of materials and experiments) and then mostly lack research evidence and are hardly tested on feasibility or effects (Eilks & Ralle, 2003). This has been taken into account in this paper and a balance between scientific evidence and practical feasibility has been pursued.

The outlined format differs vastly from conventional lecture-like communication formats; it can be applied without extensive material costs, and contains an adaptability that provides flexibility. This article attempts to achieve the following goals: (i) give a concise and application-oriented description of the specific workshop format called “myCC” and its connection to main theoretical principles of climate change communication, (ii) present the results of the initial application of this workshop format “myCC” to show what kind of results can be expected from it and (iii) outline the methodology and the results of the evaluation and impact assessment as well as the authors’ subjective observations during the application of the the workshop to show if the format leads to a positive learning effect, is accepted by the target audience and eventually even leads to multiplier/spill-over effects as well.

2. Climate change communication – theoretical background

Before the sequence plan and the specific content of the workshop format “myCC” is outlined in more detail, the underlying theoretical principles will be presented in this chapter. In order to get the students’ attention and intrinsic motivation thematically (climate change, energy, sustainability) as well as methodologically (research-based/inquiry-based learning), guidelines for successful climate change communication have been taken into account. The following six factors played a key role in the planning process of the workshop.

2.1 Education for Sustainable Development (ESD)

There is general consensus among climate scientists about the fact that mitigation and adaptation measures have to be designed in alignment with the social, economic and environmental needs – also called the “three pillars of sustainability” – of present and future generations (Monreal & Veulliet, 2010). Because education is seen as a “motor of change”, the United Nations General Assembly in December 2002, declared a Decade of Education for Sustainable Development (2005-2014) (UNESCO, 2005). Among other challenges, “fighting against global warming” by contributing to enabling citizens to face the related challenges in the present and future, was one of the top priorities on the agenda of the decade. From a theoretical point-of-view, the workshop “myCC”, was designed on the principles of the UN Decade of Education for Sustainable Development (ESD), which mirrors the concern for high quality education, demonstrating characteristics such as: critical thinking and problem solving, participatory decision making, applicability: learning experiences are integrated in day to day personal and professional life, locally relevant: addressing local as well as global issues (UNESCO, 2006).

2.2 Moderate-constructivist communication

Epistemologically compatible to ESD, the theory of Moderate Constructivism is an underlying learning theory. Not to be confused with Radical Constructivism (v. Glasersfeld, 1997), Moderate Constructivism can be seen as the current leading paradigm in learning research (Duit, 1995). Its understanding of learning may be summarized as a process that is constructive, self-determined, individual, social, and situated (Kattmann, 2003; Mandl, 2006; Terhart, 1999; Widodo 2004;). Neurobiological findings are fundamental for the moderate-constructivist understanding of learning as they show that the human brain does not simply copy images of the external world as it would not copy knowledge from another person. Instead, learning is characterized as time- and energy-intensive processes, in which neuronal structures are repeatedly activated and adapted. The human brain is not a passive recipient of stimuli but a not-determinable, autopoietic system. Individual experiences and existing foreknowledge play an important role (Roth, 1997). Consequently, knowledge-transfer/knowledge-sharing formats must be organised in a way that, construction and reconstruction of concepts is made possible by linking it to the foreknowledge and concepts of the target group (Riemeier, 2007). Nevertheless, a certain degree of instruction is needed to trigger effective learning processes (Mandl, 2006).

2.3 Know your audience

Transdisciplinary approaches require communication processes that go far beyond conventional scientist-scientist dialogues and demand extensive knowledge about the targeted audience. Despite the relatively short history of climate change communication research, a number of audience segmentation studies and case studies of communication to particular audiences have been produced (Agyeman et al., 2007; Ereaut & Segnit, 2006; Maibach et al., 2008; Michaelis, 2007; Leiserowitz et al., 2008; Rose et al., 2005). Appealing to different audiences with tailored communication has been recognized as an important strategic choice (Moser, 2007a). Therefore, once a target audience has been identified, at least the following questions should be asked: (i) What are the socio-demographics of the group? (ii) What are their current behaviours influenced by? (iii) What do they think and feel (ICLEI, 2009)? The workshop, which will be described in the following chapter, has originally been developed as a kick-off workshop for a larger research-education cooperation (cf. box in chapter 3). In the context of this project, the participating students had to take part in a detailed online survey, which gathered insights into the most important characteristics of the respective target-group involved. The students’ current knowledge, attitudes and behaviours in relation to climate change and energy as well as general socio-demographic aspects have been found out and could be used to adapt the communication approach and frame the message adequately. However, the authors did not only apply the workshop in the context of this research project but also in other contexts, which did not allow such an intensive foreknowledge about the target group. In cases like that, it is recommended to get in contact with the responsible teachers to receive information about the age of the students, the previously taught content, possible linkages with the school profile or local examples which might be relevant for the workshop.

2.4 Framing

It is of utmost importance for climate change communicators to frame their communication setting in such a way that it is not perceived as manipulative or deceiving. Instead, the message ought to be set within an appropriate context to make credible climate science more accessible to the public (Center for Research on Environmental Decisions, 2009). Being triggered by words, imagery, symbols and non-verbal cues such as music, tone of voice and gestures, framing can help communicate why an issue might be a problem, who or what might be responsible, and, in some cases, what should be done (Moser, 2010). If used effectively, frames mobilize individuals to action and are all-important communication choices with critically important implications for persuasiveness, attitude, change, trust and engagement (Green, 2002; Nisbet, 2007; Nisbet, 2009). However, there is not just one single frame to communicate climate change but several different frames focussing on various barriers. The workshop described in this paper mainly applies the two major frames, here described as “the local frame” and “the now vs. future frame”.

- The local frame: In general, people [mainly in industrialized countries but not only] perceive climate change impacts as a menace to flora, fauna and people in other parts of the world, but do not see it as a local issue affecting themselves, their community or even their family (Center for Research on Environmental Decisions, 2009). Taking this barrier into account, successful framing should highlight the current impacts of climate change on regions within the area where the audience lives.

- The now vs. future frame: According to risk researchers, people typically perceive immediate threats as more relevant and of greater urgency than future problems (Weber, 2006). Nevertheless, many communicators often portray the threat from climate change as a future rather than present risk. Many scientists focusing on the social science aspects of climate change agree that this is one of the major reasons that it is hard to motivate people to take action to prevent climate change.

These two frames have been applied in the context of the workshop by encouraging the workshop participants to find different aspects of “climate change” in their immediate environment and document the findings on a recording device.

2.5 Message

No matter how well the audience is known and how the message is framed, one of the most important questions still remains about what to convey in particular. There is no general rule of thumb which dictates what to include and what to exclude. However, a credible solution can only be found by looking at a topic from a multi-perspective, holistic point of view. Moser (2010) summarizes that the characteristics of the audience, the messenger, the channels, the place and context as well as the goals and barriers of the communication efforts should be taken into account when the message is prepared. Internal consistency and the connection between the message and existing concepts of the audience lead to effective climate change communication (Moser, 2010). Inconsistencies and audience-message mismatches produce cognitive dissonances that are likely to undermine the credibility and persuasiveness of the message (Thøgersen, 2004).

2.6 Encourage group participation

Major policy documents, ranging from the 1992 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC, 1992), which calls for parties to promote and facilitate ”public participation in addressing climate change and its effects and developing adequate responses” to more recent documents on global (e.g. IPCC 5th Assessment Report (Stocker et al., 2013) or the EU Adaptation Strategy (European Commission, 2013)), national (e.g. Austria, Germany) and federal level (e.g. Province of Tyrol/Austria) prioritise participatory approaches for climate change communication (Hohenwallner et al., 2014). However, participation processes ought to be designed aiming at long-term engagements, as climate change is irreversible on human timescales and will not be ‘solved’ quickly or easily (Moser, 2010). The level as well as the duration of engagement within the communication activity plays an important role for the success of the outcome (Swart, 2014). Especially, but not only in the co-operation with young people it is often more effective to engage them in a discussion about how they think their community can benefit from more sustainable measures and assist them in implementation rather than lecture them. Giving them hands-on opportunities can empower them and boost their potential to become climate action leaders and effective multipliers in their personal environment (Moser, 2010). Ideally, hands-on activities should have a local focus and should be organisationally integrated into a regular school curriculum, which then increases the likelihood of successful learning outcomes (Fortner & Duan, 2005; Prunea et al., 2003). The involvement in outdoor activities, which has been investigated in several studies conducted with high school students (Lisowski & Disinger, 1991) and elementary school students (Erdogan & Erentay, 2007; Erdogan et al., 2008; Erdogan et al., 2010; Martin, 2003) always proved to increase the understanding of the students’ natural environment. Connecting climate change to individual behaviour and impacts and thereby not only making abstract concepts tangible but also linking global phenomena to individual actions offers tremendous promise (Jenkins & Jenkins, 2005; Segovia & Galang, 2002).

3. Methodology

3.1 Workshop methodology

The guidelines for successful climate change communication, as explained in chapter 2, function as the theoretical base for the workshop, which will be explained in this chapter. Although it is important to follow these guiding principles from chapter 2, the circumstances of the often pragmatic and curriculum-driven school-world should always be kept in mind. Therefore, it can’t be stated often enough that a decent degree of flexibility is needed among everybody involved in education and outreach workshops like “myCC”.

“myCC” is a workshop format which was initially developed as a kick-off-workshop for a research-education-cooperation with 68 teenagers from three different Tyrolean (Austria) high-schools. The overall project, named ActAdapt – Action for Adaptation Awareness, was designed aiming at the following three main goals.

- Raising climate and energy awareness among teenagers.

- Gaining new insights in the fields of climate change communication, education for sustainable development, science education and societal transformation.

- Gaining new insights in the field of evaluation research and impact assessment.

The project ActAdapt took place from October 2013 to March 2014 and was led by a consortium made up of the three schools (Reithmanngymnasium Innsbruck, Privates Oberstufenrealgymnasium Volders, Katholisches Oberstufenrealgymnasium Zams), the research & development company alpS GmbH, the Department of Geography from the University of Innsbruck and the energy supply company TIWAG – Tiroler Wasserkraft AG.

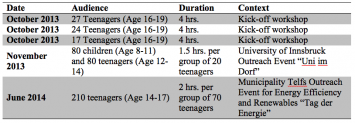

Although the workshop has originally been developed for the application in the context of the project ActAdapt – Action for Adaptation Awareness, the authors have applied it in different other contexts as table 1 demonstrates.

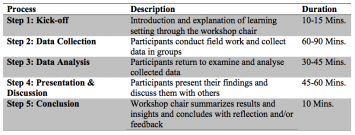

The workshop concept can be divided into the five succeeding steps (cf. Table 2) which will be explained here in more detail.

Step 1: Kick-off (10-15 Mins.)

Procedure:

In this step, the participants are informed about the procedure of the workshop and their individual tasks in it, given advice on how to use the technical equipment (audio recorder, cameras, laptops) involved and, given advice on what to respect in the process of collecting data of individual passers-by (asking for permission, politeness, etc.). In practice, the students are split up into groups of four to five participants and select one of the following tasks.

Task A: Everybody is talking about “climate change” and “energy transition”. However, it is not easy to actually see “climate change” and “energy transition” in reality. Therefore, we ask your group to grab the camera and answer the following questions by taking photos in the real world.

Task B: TV and newspapers are full of “climate change” and “energy transition”. However, what is “climate change” and “energy transition” in the minds of the people in your community and what do they know about it. We ask you to take the audio recorder and interview people in your community in order to find answers to the following questions.

The questions they receive are the same for both tasks in order to be able to compare the results afterwards.

- Where can you actually see climate change?

- Who is responsible for climate change?

- What can be done to stop climate change?

- What are you personally doing to stop climate change?

- Where can you see energy?

- Where can you see renewable energy?

- Where and how can energy be saved?

- Where and how can renewable energy be gained?

Educational comment:

Depending on the age and experience with technical equipment of the participants, the duration of this step can be adjusted. However, it is very important to allow enough time for organisational and explanatory elements at the beginning of the workshop. The workshop participants are encouraged not to spread out and collect data immediately, but instead take some time to plan their data collection and hand over tasks to different group members.

Step 2: Data collection (60-90 Mins.)

Procedure:

Every group receives a map illustrating their research area as well as a camera (Task A) or audio recorder (Task B). The size and distance of their research area have to be adapted according to the age of the students, their degree of autonomy and with regard to potential infrastructural threats (e.g. busy roads, railway tracks, rivers, etc.). The technical equipment can range from high-quality cameras and audio recorders to personal smart phones. However, data transfer cables must be provided to ensure that the data can be uploaded on the computers, laptops or tablets for the subsequent presentations and discussion. Students should be reminded of the the importance of teamwork, and that every picture they take or every interview question they ask must be based on a collective/ majority agreement within their group.

Educational comment:

The exact preparation of the group does not only prevent “solo runs”, but also makes the group discuss the research questions intensively and (hopefully also) controversially. The duration of step 2 can vary, depending on the size of research area as well as the age of the students. The authors of this article have experience in the application of this workshop and used it differently ranging from 20 minutes for Step 2 (primary school students) to 90 minutes (secondary/tertiary school students).

Step 3: Data analysis & preparing presentations (at least 45 Mins.)

Procedure:

After returning from their field work, the students are asked to upload their data, browse through it, analyse it, and come up with a collective decision on a selection of the most appropriate pictures to the previously given answers. The photos are then copied into a presentation template (e.g. Microsoft Powerpoint, Prezi, etc.), and the students are asked to prepare the subsequent presentation of their results.

Educational comment:

Instead of using a presentation template, the presentation of the pictures without text and comments is a suitable and time-efficient alternative.

Step 4: Presentation and discussion (45-60 Mins.)

Procedure:

Participants are asked to present their findings for the other groups with the help of a presentation tool (e.g. Microsoft Powerpoint, Prezi, etc). The duration of this step differs due to the size of the group, the age of the participants, and the duration of the concluding discussion.

Educational comment:

This step does not only offer the chance for a deep-going discussion at eye level between students and researchers, but also gives the researchers a possibility to match scientific knowledge with public perceptions and attitudes and learn from it.

Step 5: Conclusion (10 mins.)

Procedure:

After the presentations, the participants and the workshop chair summarize the results of the workshop and the new insights. Depending on the schedule, further general questions concerning climate change/energy/sustainability topics can be discussed.

Educational comment:

It is important that the workshop does not end with the last comment of the discussion. Instead, a summarizing conclusion that resumes the main arguments and deals as a bottom line is needed to adequately end the workshop. Of course, this does not necessarily mean that an overall solution and “the” final answer to the problem can be expected. This step is rather seen as a reflection of the insights that have been gained through the activities in step 1-4. In many cases, these final words are sacrificed in favour of step 4. However, this might lead to an abrupt and maybe dissatisfactory end for everybody involved.

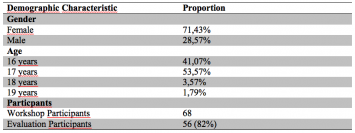

3.2 Workshop evaluation methodology

The initial application of the workshop was evaluated with the help of an online survey using the social science survey software SoSciSurvey. This software is free-of-charge and can be accessed online. 56 of the 68 participating students have been involved in the evaluation of the workshop. Table 3 outlines the demographic characteristics of the study group in this case study.

In the evaluation of this workshop, special focus was paid to three aspects, being

- the social acceptance of the workshop by the students – whether or not they liked it,

- the students self-assessment of their personal learning effect during the workshop, and

- the potential of the workshop for multiplier/spill over effects – whether or not students discussed the workshop content at home within their family afterwards.

These three aspects were evaluated with three individual items in the online survey. Both the social acceptance of the workshop and the personal learning progress are evaluated on an ordinal scale of school grades. In the case of question (i) the scale ranged from 1 (liked it a lot) to 5 (did not like it at all) and in the case of question (ii) it ranged from 1 (learned a lot) to 5 (did not learn anything at all). The third aspect of multiplier/spill over effects has been evaluated with a quantitative question and a nominal scale in which the students were asked to choose three phases of the entire project (ActAdapt) in which they particularly discussed climate change with their family members.

This form of self-assessment has been chosen not only to compare the survey results with the subjective perception of the teachers and workshop organizers about the students’ progress and degree of acceptance, but also because studies have shown that student self-assessment leads to greater awareness of themselves as learners and causes a significant increase in their achievements as well as their engagement in an activity (Black & William, 1998; Bruce, 2001; Chappuis & Stiggins, 2002; Rolheiser & Ross, 2001; White & Frederiksen, 1998). Clearly, the use of self-assessments is connected with weaknesses, as the results only show the students’ perceptions and it cannot be clearly measured whether or not the participation in this workshop eventually leads to more climate- and energy-friendly behaviour. Furthermore, an obvious weakness of these kinds of quantitative questions for self-assessments is that there is no possibility for the students to include personal remarks or give exemplary evidence to underline their individual learning progress.

4. Results

4.1 Results of the application of “myCC”

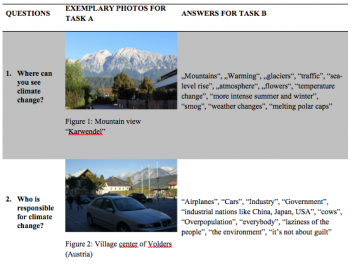

This chapter shows results that have been collected during the initial application of the workshop by teenagers from three Austrian secondary schools in the context of the project ActAdapt ). Table 4 shows examples of the data collected by the participating students in Step 2: Data Collection. Due to the fact that illustrating all data collected for Task A (answering questions by taking photos) during the initial application would be just too much information, the authors decided to choose the motives which have been photographed most frequently. Although there is no identical photograph, the motives which have been photographed by the students have been very similar. Therefore the examples in the middle column of table 4 cannot be seen as students’ concepts of climate change but rather as an outlook to inform interested readers about the results that can be expected from such a workshop. The answers to Task B (interviewing passers-by) are listed in an order representing the frequency of indication in the right column of table 4.

4.2 Results of the workshop evaluation

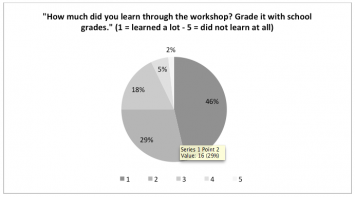

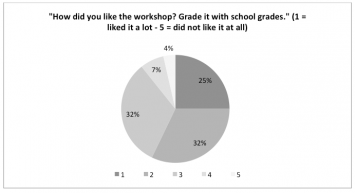

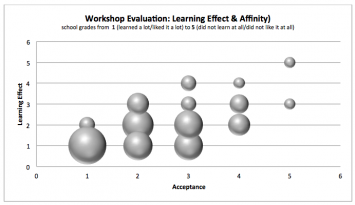

As there are many climate change communication formats which have never undergone a critical evaluation, in the case of the development of “myCC” special attention was paid to this aspect in order to find out whether or not the desired goals (learning effect & affinity by target group) could be achieved. First, the participating students assessed their individual learning effect by selecting a school grade between 1 (learned a lot) and 5 (did not learn at all). Then they selected a school grade ranging from 1 (liked it a lot) to 5 (did not like it at all) on another ordinal scale to express whether or not they liked the workshop.

Figure 9: Illustration of the workshop evaluation results showing the learning effect of the workshop by the participating students (n=56)

Figure 10: Illustration of the workshop evaluation results showing the affinity to the workshop by the participating students (n=56)

In figure 11, the results of the combination of both questions are illustrated. The diameter of the individual bubbles in figure 11 represents the number of students who chose this combination in their evaluation. The distribution of the bubbles, with an agglomeration of big bubbles in the bottom left quadrant of the figure clearly shows that the majority of students evaluated the workshop positively. This means they do not only report to like and accept the workshop but also that taking part in it resulted in a learning effect.

Figure 11: Illustration of the workshop evaluation results (Table 4) by the participating students (n=56)

However, the evaluation results, collected with the Austrian school grade scale (1-5), only allow for a first assessment and are not enough for an in-depth analysis of the workshop. Hence, this evaluation does not provide detailed information about the relevant characteristics that have finally been responsible for this result.

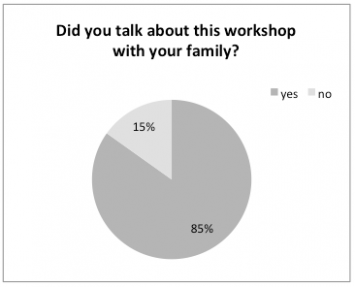

Since the workshop format does not only target the students themselves but was designed to also address their social environment (e.g. family members) and thereby use potential multiplier/spill-over effects, it was of interest to find out which effects “myCC” had in this respect. Figure 11 shows the results of an item in the online survey, in which students have been asked to report whether or not they talked about the workshop with their family members after they had participated in it.

Only 15% reported to have not talked about the workshop in their family, the overwhelming majority of 85%, however, said that they did talk about the workshop with their family members. Therefore, it can be stated that the de-facto target-group of the workshop has been augmented and the students took over the role of multipliers in their families. However, an obvious limitation to this second item is that the authors do not exactly know what the content of the conversation between the students and their family members was. It cannot be said whether they reported positively or negatively about the experience of taking part in the workshop. But still, the workshop format led to a follow-up conversation which can be interpreted as promising.

5. Discussion and conclusion

Not only the authors’ subjective observations during applying the workshop “myCC” in different contexts, but also the evaluation of the initial application of the workshop, allow for the beginnings of a critical assessment and recommendations for practitioners.

According to the results of the evaluation of the initial application of the workshop, the previously stated goals of the workshop have been achieved as follows:

- Combination of affinity and learning effect: The results of the evaluation of the workshop in Table 5 and Figure 9 clearly show that a vast majority of the students, who took part in the workshop, reported that they did not only like the workshop but that it also had a positive learning effect on them. Therefore, it can be said that the desired combination of social acceptance of a certain format and the perception of it to have a positive learning effect has been achieved with this workshop. Formats with only a high acceptance do not have the same value and impact as “myCC” does. However, the evaluation results are not enough to make a statement about the characteristics that have been responsible for these positive results in the end. Therefore, further research is needed to find out exactly which elements make a difference.

- Making use of multiplier/spill-over effects: Known as the “nag-factor” (Holly, 2011) among marketers, the effect children and teenagers have on their parents’ decisions should not be underestimated. Therefore, the authors attempted to use this factor for a positive effect on a common good – our climate. So far, there is not much published work about the effect children and teenagers have on their parents when it comes to climate-sensitive decisions. Although the results of the workshop evaluation in figure 10 do not tell much about the multiplier effects, they are first evidence that the workshop “myCC” was of such interest that it was worth a discussion after the students participated in it. However, this field demands much more attention and research to get more insightful results about this very promising aspect.

In addition to the above mentioned evaluation results, the authors’ subjective observation during applying the workshop “myCC” in different contexts (cf. Table 1) with different target groups, led to the identification of the following aspects as positive characteristics of the workshop:

- High level of adaptability: With an adaptable time frame and a suitable level of complexity in the discussion, the workshop can easily be used in primary, secondary and tertiary education without time-, cost- and material-intensive preparation. In contrast to worksheets, roll-ups, movie clips or similar outreach formats and materials, the workshop could easily be adjusted and “updated” with the latest state-of-the-art in climate change research.

- High level of engagement: Participating students are not confronted with incoherent climate change information, but, instead, they take over a very active role, share their personal knowledge as well as their perceptions, and discuss the topic based on their personal research results during the workshop. This enables a bilateral exchange at eye-level between researchers and students. However, this only happens, if the students’ research results are not seen as final results but rather as a kick-off for intensive discussions about the photos and the survey data. Therefore, the authors want to point out the importance of a competent moderation and enough time for the discussion. Previous applications of the workshop showed that it helped to ask the students to exactly point at the spot of the picture which answers the question (Task A) or to comment and interpret the collected survey results (Task B). However, there is a lot of sensitivity and empathy needed to turn the presentation into a satisfying discussion.

- (Science) competence-orientation: Trust in science in general and climate science in particular is of utmost importance in the debate about climate change. Therefore, a science-education approach has been chosen not only to engage young people in the debate but also to introduce them to scientific mind-sets and research methods. Thereby “myCC” does not only deliver information, but attempts to promote the acquisition of competences among participating students. However, sound statements about the actual competence acquisition cannot be made as it has not been focused in the evaluation and because the field of competence measurement in general is still in the early stages of development.

- Low level of technology- and material-dependence: Scarcity in technological equipment is a wide-spread issue amongst education facilities. Therefore, “myCC” makes use of the technical equipment that is available among children and teenagers anyway. With average smart phones and at least one computer, the workshop can be held. This low level of technology- and material-dependence reduces the workshop expenses, preparation efforts and material intensity.

- Connecting a global challenge with contemporary local examples: As outlined in chapter 2, the fact that climate change is a global phenomenon, makes it very difficult to communicate. Therefore, it was of utmost importance to get from telling people about climate change impacts to encouraging them to actively search and identify “visible” climate change impacts in their environment and even further, to develop own climate change mitigation measures. This participatory and moderate-constructivist approach was chosen because the authors think that direct contact with climate change impacts is a much more intense experience and co-developing measures against it increases the ownership and thereby the likelihood of application.

- Combining application-orientation with current climate change communication theory: The development of “myCC” was based on internationally acknowledged and contemporary factors for successful climate change communication. However, no matter how evidence-based a format is, it won’t have any effect on the society without a user-friendly and comprehensive delivery of it.

The results of the evaluation and the authors’ subjective observations show that “myCC” can be an example of successful climate change communication with the engagement of young people. The workshop encourages the participants to actively search for local climate change impacts and solutions that are applicable here and now. Thereby, a global and intangible phenomenon like climate change is tackled by a simple workshop combining individual perceptions, local examples as well as down-to-earth solutions. Of course, these solutions alone are not enough to master the challenge, but they might empower the participants and show them that climate change mitigation (and adaptation) does not have to be difficult, expensive or exhausting. Especially, the fact that students are not instructed with knowledge and persuaded to change their attitude and/or behaviour, but instead encouraged to see climate change through their very own eyes and come up with their very own ideas to tackle climate change challenges, ensures a greater acceptance and effectivity among the target-group. However, neither through the observation nor through the evaluation with the online survey, statements concerning actual behavioural change can be made. To find out whether the workshop finally leads to energy-efficient behaviour or more climate-friendly decisions among the participants, long-term monitoring would be needed. Measuring and quantifying the impacts of climate change communication activities still needs further research. The “default formula” (Adensam et al., 2013), which is used in the impact assessment of energy audits, could be used as a potential linkage to make a more quantitative sound statement about the (financial) impacts of climate change communication activities.

From a science perspective, this workshop format is promising as it does not only deal as an education and outreach format, but also provides feedback by future decision makers to current efforts in climate change science and policy as well as generates insights into subjective perceptions and concepts of climate change and related topics. Although this paper focused on the application of the workshop in an education and outreach context, further fields of application exist including stakeholder-involvement processes with local actors.

Acknowledgements

This research is funded under the COMET – Competence Centers for Excellent Technologies program by Austrian Federal Ministry of Transport, Innovation and Technology (BMVIT), Austrian Federal Ministry of Science, Research and Economy (BMWFW) and the province of Tyrol.

6. Bibliography

Adensam, H., Bogner, T., Geissler, S., Groß, M., Hofmann, M., Krawinkler, R., Kulterer, K., Ploiner, C., Renner, S., SImader, G., Thenius, G., Tretter, H., (2013). Methoden zur richtlinienkonformen Bewertung der Ziellerreichung gemäß Energieeffizienz- und Energiedienstleistungsrichtlinie 2006/32/EG. Bottom Up Methoden. Retrieved from http://www.bmwfw.gv.at/EnergieUndBergbau/Energieeffizienz/Documents/Methodendokument_RK_AT_131015.pdf

Agyeman, J., Doppelt, B., Lynn, K., Hatic, H. (2007). The climate justice link: communicating risk with low-income and minority audiences. In: Moser, S., Dilling, L., (Eds.), Creating a Climate for Change: Communicating Climate Change and Facilitating Social Change (pp.119-139). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press,

Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (1998). Inside the black box: Raising standards through classroom assessment. Phi Delta Kappan, 80(2), 139–148

Bruce, L. B. (2001). Student self-assessment: Encouraging active engagement in learning. Dissertation Abstracts International, 62-04A, 1309.

Center for Research on Environmental Decisions. (2009). The Psychology of Climate Change Communication: A Guide for Scientists, Journalists, Educators, Political Aides, and the Interested Public. New York. Retrieved from http://guide.cred.columbia.edu/pdfs/CREDguide_full-res.pdf

Chappuis, S., & Stiggins, R. J. (2002). Classroom assessment for learning. Educational Leadership, 60(1), 40–43.

Duit, R. (1995). Zur Rolle der konstruktivistischen Sichtweise in der naturwissenschaftsdidaktischen Lehr-Lernforschung. Zeitschrift für Pädagogik, 41(6):905–926

Eilks, I., & Ralle, B. (2002). Participatory Action Research in chemical education. In B. Ralle, I. Eilks (Eds.) Research in Chemical Education – What does this mean? (pp. 87-98) Aachen: Shaker

Erdogan, M., & Erentay, M. (2007). Children’s perceptions on endangered species and threatened environments: results from Unique and Universal Project. In M. F. Costa, B. V. Dorrfo & R. Reis (Eds.), Development, Diversity and Inclusion in Science Education (pp. 141-148). University of Azores, Ponta Delgada, Portugal: The Hands on Science Network.

Erdogan, M., Erentay, N., Barss, M., & Necbita, A. (2008). Students’ awareness of endangered species and threatened environments: A comparative case-study. International Joumal of Hands-on Science, I (2), 46-53.

Erdogan, M., Erentay, N., Aydogan, B., Çelik, M., Çmar, 0., Balaban, D., et al. (2010). Expanding the horizons through field trips: Developing global action plan for saving endangered species and threatened environments. In M. Kalogiannakis, D. Stavrou, & P. Michaelidis (Eds.), Proceedings of the 7th Intemational Conference on Hands-on Science (pp. 398-403). Rethymno-Crete.

Ereaut, G., Segnit, N., (2006). Warm Words: How Are We Telling the Climate Story and Can We Tell It Better? Retrieved from http://www.ippr.org/assets/media/images/media/files/publication/2011/05/warm_words_1529.pdf

European Commission (2013). Horizon 2020. Call for integrating society in science and innovation. Retrieved from http://ec.europa.eu/research/participants/portal/desktop/en/opportunities/h2020/calls/h2020-issi-2015-1.html

Fortner, R., & Duan. H. (2005). Chinese College Students’ Perceptions about Global versus Local Environmental Issues. The Journal of Environmental Education, 36 (4): 23–58.

Haynes, K., Lassa, J., Towers, B. (2010). Child-centred disaster risk reduction and climate change adaptation: roles of gender and culture in Indonesia. Children in a Changing Climate Working Paper II, Brighton: IDS

Hohenwallner, D., Anderl, M., Bürgel, J., Goler, R., Hama, M., Huber, T., Ibesich, Nikolaus, Kratzer, A., Krutzler, T., Lampert, C., Leitner, M., Link, S., Nagl, C., Rigler, E., Schmid, C., Schneider, J., Schieder, W., Schröer, K., Schwab, K., Steuer, S., Storch, A., Strobl, H., Zethner, G. (2014). Klimastrategie Tirol. Klimaschutz- und Klimawandelanpassungsstrategie Tirol 2013 – 2020. Retrieved from https://www.tirol.gv.at/uploads/media/310114_KLIP_Tirol_Synthesebericht.pdf

Holly, K. M., Borzekowski. H., Borzekowski. D. (2011). The ‘Nag Factor’ a mixed-methodology study in the U.S. of young children’s requests for advertised products. Journal of Children and Media 5(3), 298-317. doi: 10.1080/17482798.2011.584380

Illietschko, P. & Taschwer K. (2014, March 25). „Wir waren bis jetzt zu defensiv“ – Interview with Pascale Ehrenfreund and Anton Zeilinger. Der Standard. Retrieved from http://derstandard.at/1395363188260/Wir-waren-bis-jetzt-zu-defensiv

Jenkins, K. A., & Jenkins, B.A. (2005). Education for Sustainable Development and the Question of Balance: Lessons from the Pacific. Current Issues in Comparative Education, 7 (2): 114–29.

Kattmann, U. (2003). Vom Blatt zum Planeten – Scientific Literacy und kumulatives Lernen im Biologieunterricht und darüber hinaus. In B. Moschner, H. Kiper, U. Kattmann (Eds.) PISA 2000 als Herausforderung. Hohengehren/Baltmannsweiler: Schneider

Leiserowitz, A., Maibach, E., and Roser-Renouf, C. (2008) Global Warming’s “Six Americas”: An audience segmentation. Yale University and George Mason University. New Haven, CT: Yale Project on Climate Change. Retrieved from http://environment.yale.edu/climate-communication/files/climatechange-6americas.pdf

Lisowksi, M., & Disinger, J. E. (1991). The effect of field-based instruction on student understandings of ecological concept. The Joumal of Environmental Education, 23 (1), 19-23.

Maibach EW, Roser-Renouf C, Leiserowitz A. (2008). Communication and marketing as climate change intervention assets: a public health perspective. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 35:488–500.

Mandl, H. (2006). Wissensaufbau aktiv gestalten. In G. Becker, I. Behnken, H. Gropengießer, N. Neuß (Eds.) Lernen. (pp.28-30). Seelze: Friedrich

Martin, S. C. (2003). The influence of outdoor schoolyard experiences on students’ environmental knowledge, attitudes, behaviour and comfort level. Joumal of Elementary Science Education, 5(2)

Michaelis L. (2007). Consumption behavior and narratives about the good life. In SC. Moser, L. Dilling, (Eds.) Creating a Climate for Change: Communicating Climate Change and Facilitating Social Change. (pp. 251–265). Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press

Mitchell, T., Haynes, K., Hall, N., Choong, W., Oven, K. (2008). The Role of Children and Youth in Communicating Disaster Risk. Children, Youth and Environments, 18, 254-279.

Mitchell, T., Tanner, T., Haynes, K. (2009). Children as agents of change for Disaster Risk Reduction: Lessons from El Salvador and the Philippines. CCC Working Paper 1. Brighton: IDS. Retrieved from http://www.plan-uk.org/resources/documents/37225/

Monreal, M. & Veulliet, E. alpS – Centre for Climate Change Adaptation Technologies In: E. Veulliet, A. Borsdorf, A., G. Grabherr, K. Heinrich, B. Scott & J. Stötter (Eds.) (2010). Challenges for Mountain Regions – Tackling Complexity. Wien: Böhlau.

Moser, SC. (2007a). Communication strategies to mobilize the climate movement. In J. Isham, S. Waage (Eds.) Ignition: What You Can Do to Fight Global Warming and Spark a Movement. Washington, D.C.: Island Press; 73–93.

Moser, SC. (2007b). In the long shadows of inaction: the quiet building of a climate protection movement in the United States. Global Environmental Politics 7:124–144.

National Center for Education Statistics (2007). Science Achievement of Fourth- and Eighth-Graders between 1995 and 2007 Retrieved from http://nces.ed.gov/timss/results07_science95.asp

Nature Neuroscience (2009). Encouraging science outreach. Editorial. Nature Neuroscience 12. Retrieved from http://www.nature.com/neuro/journal/v12/n6/full/nn0609-665.html

Nisbet, MC. & Mooney, C. (2007). Framing science. Science, 316:56.

Nisbet, MC. (2009). Communicating climate change: why frames matter for public engagement. Environment 51:12–23.

Poliakoff, E., & Webb., T.L. (2007). What factors predict scientists’ intentions to participate in public engagement of science activities? Science Communication 29(2):242–263.

Pruneau, D., Gravel, H., Bourque, W. & Langis, J. (2003). Experimentation with a Socio- constructivist Process for Climate Change Education, Environmental Education Research, 9(4): 429–46.

Riemeier, T. (2007). Moderater Konstruktivismus. In D. Krüger & H. Vogt (Eds.) Theorien in der biologiedidaktischen Forschung. (pp. 69-80). Springer XIV.

Rolheiser, C., & Ross, J.A. (2000). Student self-evaluation – What do we know? Orbit, 30(4), 33–36.

Rose, C., Dade, P., Gallie, N., Scott, J. (2005). Climate Change Communications – Dipping A Toe Into Public Motivation. Retrieved from www.campaignstrategy.org

Rose, C, Dade P, Scott J. (2007). Research Into Motivating Prospectors, Settlers and Pioneers To Change Behaviours That Affect Climate Emissions. Retrieved from http://www.campaignstrategy.org/articles/behaviourchange_climate.pdf

Roth, G. (1997). Das Gehirn und seine Wirklichkeit. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp

Royal Society (2006). Survey of factors affecting science communication by scientists and engineers. Royal Society. London, UK. Retrieved from http://www.peoplescienceandpolicy.com/downloads/Science_communication_technical_report_NAV.pdf

Segovia, V.M. & Galang. A.P. (2002). Sustainable Development in Higher Education in the Philippines: The Case of Miriam College. Higher Education Policy, 15 (2), 187–95.

Sparkling Science. (2014). Sparkling Science – ein Programm des Bundesministerium für Wissenschaft, Forschung und Wirtschaft. Retrieved from http://www.sparklingscience.at/en/

Swart, R., Alberth, J., Kuna, B., Lillieskold, M., Hanzlickova, M., Horstmann, B., Rovisco, A. (2014). Learning through collaboration – Knowledge Transfer and Sharing in Climate Change Adaptation Research between European and developing countries. A CIRCLE-2 research policy brief. Foundation of the Faculty of Sciences, University of Lisbon, Portugal.

Tanner, T. (2010). Shifting the Narrative: Child-led Responses to Climate Change and Disasters in El Salvador and the Philippines. Children and Society, 24, 339-351

Tanner, T.M., Garcia, M., Lazcano, J., Molina, F., Molina, G., Rodríguez, G., Tribunalo, B., Seballos, F. (2009). Children’s participation in community-based disaster risk reduction and adaptation to climate change. Participatory Learning and Action, 60, 54-64.

Thøgersen, J. A. (2004). Cognitive dissonance interpretation of consistencies and inconsistencies in environmentally responsible behavior. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 24:93–103.

Sisk, T.D., Singh, G., Tam, J., Chan, K.M.A., Klain, S., Mach, M., Martone, R. (2011). Barriers and Incentives to Engagement in Public Policy and Science-based Advocacy. Bulletin of the Ecological Society of America 92:276–280. http://dx.doi.org/10.1890/0012-9623-92.3.276

UNESCO (2005). UN Decade of Education for Sustainable Development. Retrieved from http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0014/001416/141629e.pdf

UNESCO (2006). Framework for the UNDESD International Implementation Scheme. Retrieved from http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0014/001486/148650E.pdf

UNESCO (2010). The UNESCO Climate Change Initiative. Climate Change Education for Sustainable Development. Retrieved from http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0019/001901/190101E.pdf

UNFCCC (1992). United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Retrieved from http://unfccc.int/resource/docs/convkp/conveng.pdf

von Glasersfeld, E. (1997). Radikaler Konstruktivismus. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main

Widodo, A. (2004). Constructivist oriented lessons. Europäischer Verlag der Wissenschaften, Frankfurt am Main

Walden, D., Hall, N., Hawrylyshyn, K. (2009). Participation and Protection: Children‟s Involvement in Climate Change Debates. Focus 13.4 Brighton: IDS

Weber, E. U. (2006). Experience-based and description-based perceptions of long-term risk: why global warming does not scare us (yet). Climatic Change, 77(1-2), 103-120.

White, B. Y., & Frederiksen, J. R. (1998). Inquiry, modeling, and metacognition: Making science accessible to all students. Cognition and Instruction, 16(1), 18–31.

Corresponding Author: Mag. Dr. Maximilian Riede, alpS – Centre for Climate Change Adaptation & University of Innsbruck, Austria. E-Mail: maximilian.riede@uibk.ac.at

Senior Researcher at alpS Centre for Climate Change Adaptation, Innsbruck/Austria; Researcher and Lecturer for Education in Geography at Institute of Geography, University of Innsbruck/Austria

Senior Researcher at alpS Centre for Climate Change Adaptation, Innsbruck/Austria; Researcher and Lecturer for Education in Geography at Institute of Geography, University of Innsbruck/Austria  Assistant Professor at the Institute of Geography, University of Innsbruck/Austria, Key Researcher at alpS-Centre for Climate Change Adaptation, Innsbruck/Austria; Co-Editor of the didactical journal GW-Unterricht, Vienna/Austria

Assistant Professor at the Institute of Geography, University of Innsbruck/Austria, Key Researcher at alpS-Centre for Climate Change Adaptation, Innsbruck/Austria; Co-Editor of the didactical journal GW-Unterricht, Vienna/Austria  PhD Candidate and Senior Lecturer at Institute of Geography, University of Innsbruck/Austria, Co-Editor of the didactical journal GW-Unterricht, Vienna/Austria

PhD Candidate and Senior Lecturer at Institute of Geography, University of Innsbruck/Austria, Co-Editor of the didactical journal GW-Unterricht, Vienna/Austria  Energy Community Manager, Beegy GmbH, alpS Centre for Climate Change Adaptation, Innsbruck/Austria

Energy Community Manager, Beegy GmbH, alpS Centre for Climate Change Adaptation, Innsbruck/Austria