Building Community Through Engaged Students: CommUniverCity and Experiential, Service-Based Education

Abstract

Experiential learning, and more specifically, service learning (SL) can serve as an ideal mechanism to support sustainability education. In particular, because of its emphasis on collaboration between students, faculty, and the community partner(s) and on social change and civic engagement, SL provides an excellent vehicle to address issues related to social justice. In this article, we document a unique SL partnership at San José State University—CommUniverCity. CommUniverCity’s primary mission is to build social capital and empower residents in an underserved community near the university. Each year, students, faculty and residents invest more than 21,000 hours in service to the community. Because of its unique mission, sustainability-related projects lie at the heart of what CommUniverCity does. We analyze student surveys from more than 30 classes engaged in SL projects during 2012 across a wide range of disciplines. All projects address at least one, and often multiple “Es” of sustainability. Our findings indicate that students find value in the SL experience, not only in terms of better understanding of the course subject matter, but also in terms of their understanding of “community” and the larger issue of social justice and equity.

Keywords: service learning; experiential learning; higher education; community empowerment; social justice; social capital; sustainability

Introduction

The core tenet of experiential learning—that of learning through direct experience—has been encouraged in our educational system for decades. Service learning (SL) is one form of experiential education that engages students in service with the community. Unlike other forms of experiential education, SL emphasizes collaboration between students, faculty, and the community partner(s) and also focuses on lasting social change and a more engaged civic sector (Seifer, 1998). It can be an ideal mechanism to support sustainability education, particularly aspects of sustainability related to equity and social justice.

The integration of sustainability into the curriculum and actions of higher education institutes in the U.S. is not new, although it is a growing trend (Rowe, 2007). In addition, the inclusion of real-world, experiential learning opportunities in sustainability curriculum is encouraged.

Imagine what might happen if students were regularly assigned actual sustainability problems that were brought to higher education by cities, businesses, non-profit organizations, and other institutions. If classroom exercises produced workable contributions to solutions, students would understand they can have a positive impact on the world through their academic learning. (Rowe, 2007, p. 324)

Brundiers, Wiek, and Redman (2010) present a case study from Arizona State University on how real-world learning opportunities can assist students with learning key sustainability competencies. According to the authors, SL is particularly effective at addressing sustainability aspects related to social innovation and change. This article documents a unique service learning partnership at San José State University that has, as its primary mission, to build social capital and empower community members in an underserved neighborhood surrounding the campus.

CommUniverCity: A Service Learning Partnership to Build Social Capital

CommUniverCity is a unique partnership for service, learning, and empowerment between three vital, and equal, partners: the community, a group of underserved, low-income, predominantly minority neighborhoods in Central San José; San José State University (SJSU); and the City of San José.

Table 1 presents the demographic and socio-economic composition of the community component of CommUniverCity compared to the City of San Jose and Santa Clara County. The CommUniverCity community comprises eight separate “neighborhoods” in downtown San José, within a distance of approximately 1 mile of SJSU. The neighborhoods represent about 10% of the total city population and are quite different in terms of their demographic and socio-economic composition; a majority of residents are Hispanic, median household income is about $20,000 less than the citywide median value (nearly $30,000 less than the County), and the overall level of formal education attainment is also lower than the City or County.

Table 1 Comparison of Demographic and Socio-economic Characteristics, 2010

|

CommUniverCity Neighborhoods |

San Jose, CA |

Santa Clara County |

|

| Total population |

96,006 |

945,942 |

1,781,642 |

| White, non-Hispanic (%) |

23.4 |

33.2 |

35.2 |

| Hispanic (%) |

54.1 |

28.7 |

26.9 |

| Asian, Non-Hispanic (%) |

15.8 |

31.7 |

31.7 |

| Black, non-Hispanic (%) |

3.6 |

2.9 |

2.4 |

| American Indian/Alaska Native, non-Hispanic (%) |

0.3 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, non-Hispanic (%) |

0.3 |

0.4 |

0.4 |

| Other, including multiple race, non-Hispanic (%) |

2.5 |

2.9 |

3.2 |

| College graduate (%) |

27.4 |

36.6 |

45.3 |

| Median household income |

$59,174 |

$79,405 |

$86,850 |

| Source: U.S. Census Bureau. Census 2010, Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics. Generated by Hilary Nixon, using American FactFinder; <http://factfinder2.census.gov>; (January 10, 2013). | |||

CommUniverCity began in 2005 with a primary mission to build community by engaging residents and students in service learning projects that meet neighborhood-driven goals.1 Service learning projects are in the following areas (Fig. 1):

- Education: enrich and expand educational opportunities for research and youth, encouraging a “College-Going” culture through the community.

- Community Health: support all aspects of the neighborhood that contribute to healthy environments and lifestyles.

- Neighborhood Environment: Foster a physically safe and socially connected, empowered community.

While service-learning partnerships exist elsewhere, several factors set CommUniverCity apart. First, CommUniverCity emphasizes a single geographical area, Central San José.2 This fosters a greater cumulative impact compared to scattered, independent projects, which tend to be quite common in other service learning programs. This geographic concentration also supports another important component: interdisciplinary cooperation and learning. Having a large number of projects in a variety of disciplines promotes cross-fertilization between faculty and students from across campus. Another key factor is the long-term commitment to the community. CommUniverCity originally started with a five-year commitment from the university. This has been extended and there are no foreseeable plans to curtail the university’s support. A city administrator in San José during the initial program development commented, “Most service-learning projects are like one-night stands, but what we’re hoping for here is more like a marriage—or at least a long-term affair.” Two final factors that contribute to CommUniverCity’s uniqueness are the role of community residents and a goal to build social capital in the community. Service learning projects tend to be faculty-driven, although sometimes in consultation with the community. For CommUniverCity, the community sets project priorities and then faculty and classes are identified to work on the projects. The goal to build social capital in the community was not undertaken lightly (Christensen & Jackson, 2009). At a minimum, all projects must directly involve members of the neighborhood and, more broadly, foster positive relationships within the community.

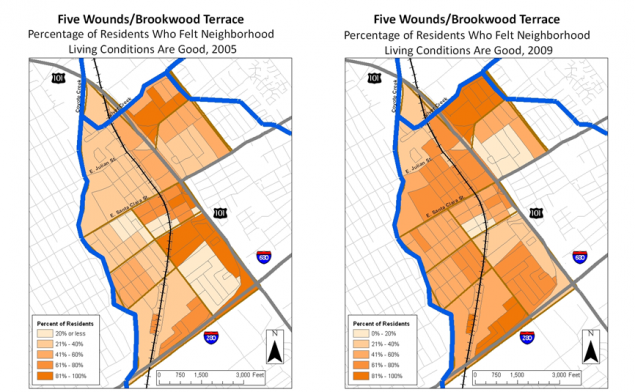

Each year, more than 1,400 SJSU students work collaboratively within excess of 5,600 neighborhood residents on projects designed to meet neighborhood-driven goals. On average, the faculty, students, and residents collectively invest more than 21,000 hours in the community. Since 2005, CommUniverCity has invested over 150,000 hours of service towards community development efforts in the neighborhoods, valued at over $3M. The types of project vary widely but all fall within one of the three areas of focus. All projects contribute to the overarching goal of building social capital. Given its emphasis on a long-term commitment and on positive change in the neighborhood, an evaluation of the impact of the projects on resident attitudes is important. One ongoing project since CommUniverCity’s establishment is an annual survey of residents to assess opinions related to how well it is meeting established goals. Figure 2 shows the change in percentage of residents in Five Wounds/Brookwood Terrace (the original neighborhood of focus for CommUniverCity) rating their neighborhood living conditions as “good” over a five-year period. As you can see from the map, overall residents’ opinions on living conditions in their neighborhood improved during the time period. Of course, from these results, it is impossible to ascertain that CommUniverCity was the cause of the change in attitude. However, they do suggest some type of relationship between its involvement in the community and improved resident attitudes toward the neighborhood.

Fostering Social Justice Through Service Learning

Projects related to sustainability have been at the heart of CommUniverCity’s work since its establishment in 2005. Signature sustainability projects include Garden to Table, a neighborhood agriculture project, and Pathways to Active and Healthy Living, a project that addresses environmental and land use policy changes that increase walkability and connectivity in the neighborhood, thus encouraging active lifestyles and discouraging reliance on the automobile. Moreover, issues related to social justice and equity tend to be at the forefront of what CommUniverCity does. Most of the projects aim to develop a “college-going culture” by engaging SJSU students to support the academic success of school children, which in turn enhances their future career and lifelong earning potential and therefore their opportunities to lift themselves out of poverty. SJSU students mirror the diversity of the neighborhoods surrounding the campus, and they become a model for neighborhood children and their parents to chart a trajectory towards higher education.

While a primary goal for CommUniverCity is to build social capital in the community by working on neighborhood driven projects, the impact of the work on students and student learning is essential. It is, after all, a service learning partnership. Students engaged in service learning projects with CommUniverCity all complete a pre- and post-course survey. The purpose of the survey is to develop a better understanding of the current state of civic engagement among students at SJSU, to evaluate the potential impact of a CommUniverCity service learning project on a student’s likelihood to become more civically engaged, and to assess the impact of the project on a student’s learning. For the purposes of this article, we focus our analysis on projects that took place during 2012. Table 2 presents a selection of service learning projects including the SJSU department involved, a brief description of the project, and an indication of the sustainability component (the 3 Es—economics, environment, equity) that the project addresses.

Table 2 Selected CommUniverCity Service Learning Projects, 2012

| Project Title |

Department(s) |

Description |

Sustainability Coverage (The 3 Es) |

| Garden To Table | Communication Studies; Nutrition & Food Sciences; Urban & Regional Planning | G2T works to increase access to and affordability of healthy food resources. Specific components include a community garden, school garden (elementary school), apartment gardens (building gardens and conducting workshops at multifamily apartment complexes), and a gleaning program. G2T also coordinates a “Green Chef” program where students use produce available at a local food bank to teach participants how to create nutritious and healthy meals and facilitates a “Cooking Matters” workshop series to teach parents and children about nutrition, meal-planning, and healthy cooking. | EconomicsEnvironmentEquity |

| Record Clearance Project | Justice Studies | RCP gives students hands-on experience assisting eligible residents to clear criminal convictions. Students learn about expungement law and various other legal skills. With over 65 million Americans (and 1 in 4 Californians) holding a criminal record, RCP works to make equal access to justice a reality by providing free legal services to clients who cannot pay attorneys’ fees. Once their records are cleared, clients have access to higher paying jobs; housing assistance, food stamps and family benefits, enabling them to support their families and add to the economy. A short video showcasing the impact on clients is available at: http://youtu.be/G-T1TdH1zgc | EconomicsEquity |

| Spartan-Keyes Participatory Neighborhood Planning | Urban & Regional Planning | Students worked with community members in a participatory community planning process to revisit neighborhood priorities and identify the top 10 neighborhood priorities. Students engaged the community to develop specific recommendations for improving dilapidated, dangerous alleyways in the neighborhood; developing services for underrepresented youth; increasing the availability of open space in the community; enhancing the pedestrian environment to encourage walking; and “greening” the neighborhood by creating food growing gardens and planting trees. | EnvironmentEquity |

| Writing Partners | English | Students engage with elementary students as “pen pals” to develop early writing skills and also to promote a neighborhood priority to develop a “college-going culture.” | Equity |

| Tax Institute | Business | Students conduct a series of tax workshops for residents and small business owners. | EconomicsEquity |

| Safe & Green Halloween | Hospitality, Recreation, and Tourism Management | Students and residents organize a fiesta to promote environmentally sustainable and safe alternatives to celebrating Halloween while building connections with their neighbors. The event draws 700 residents on average. A highlight of the event is a contest for Halloween costumes made entirely out of recycled materials. | Environment |

| Social Capital Survey | Political Science | Students conduct a door-to-door survey of trust and civic engagement in the community. | Equity |

| Housing and Financial Literacy, | Business | Students conduct a series of workshops for adults and children on a variety of financial literacy topics including banking and budgeting, and how to prepare financially to buy a home. | EconomicsEquity |

| Marketing Smarts | Business | Students serve as consultants to women micro-entrepreneurs who are interested in starting and/or developing their businesses. | EconomicsEquity |

| STEM Community | Chemistry, Biology, Engineering | Students conduct a series of modules on renewable energy and plant biology for 5th-8thgrade students enrolled in afterschool programs. Participating school children increase their interest in STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) fields, and SJSU students discover a passion for teaching science. | EnvironmentEquity |

| Engineering in Action | Biomedical, Chemical, and Materials Engineering; Aerospace Engineering | Students design and present hands-on workshops with K-12 students to showcase engineering concepts, including renewable energy and aerodynamics. The projects not only help SJSU students learn the engineering concepts better, but also serve to promote a neighborhood priority to develop a “college-going culture” through increased interactions with university students and faculty. | Equity |

| Pathways to Healthy and Active Lifestyles | Political Science, Urban Planning | Students and residents collaborate on three interconnected projects that promote active commuting, use of public transit, and the expansion of open space in the community. The projects entail the development of a land use plan for a multi-use Transit Village station for the future station of a local commuter train (the plan has been integrated in the City of San José’s General Plan 2040), the conversion of an abandoned railroad track to a multi-purpose trail, and “safe routes to school” improvements and programs at 3 neighborhood schools. | Environment |

| Art on the Block | Art; Sociology; Urban Planning | Students and residents organized an art festival in the neighborhood park, designed to build community and strengthen neighborhood identity. A major feature of the event was the introduction of an art installation in the community made entirely of recycled material. | EnvironmentEquity |

| Senior Wellness Fair | Social Work, Kinesiology, Health Science, Occupational Therapy, Nursing, Nutrition, Psychology | Students organized a fair to provide over 300 low-income seniors with resources that encourage a healthy lifestyle. Students provided free health screenings and education that gave them exposure to resources available to seniors and their families. | Equity |

In 2012, more than 30 classes engaged in CommUniverCity service learning projects. Academic disciplines ranged widely and included Art, Business, Communication Studies, Education, Engineering, English, Hospitality, Recreation & Tourism Management, Justice Studies, Nutrition & Food Sciences, Mexican American Studies, Political Science, Sociology, Kinesiology, Social Work, and Urban & Regional Planning—every College at SJSU was represented. Because of the three neighborhood-driven goals and CommUniverCity’s overall mission to build social capital in the community, all projects address at least one of the three Es of sustainability—economics, environment, equity.

In general, we see no statistically significant difference in students’ commitment to civic engagement after participating in a CommUniverCity SL course. However, our survey results suggest that SJSU students have a fairly strong commitment even before participating. More than 80% of students surveyed (both in the pre- and post-course surveys) agreed with the statement, “Individuals have a responsibility to help solve our social problems.” In addition, approximately two-thirds (Fall 2012) to three-quarters (Spring 2012) of students agreed with the statement that they “plan to become involved in my community” during the pre-course survey with no statistically significant difference in levels of agreement during the post-course survey. In fact, approximately three-quarters of respondents indicated that they had previously engaged civically during the previous year, either through involved with a community organization, political organization, or similar civic/political activity. These results are not particularly surprising given SJSU’s recent emphasis on community-based learning (see, e.g. Briggs, n.d.) and mission to promote responsible citizenship (San José State University, 2011).

On the post-course survey, students are asked to identify how much the CommUniverCity project contributed to their learning in the class. A total of 327 students responded. Almost half of the students (43%) stated that the project contributed “a great deal” or “quite a bit” to their learning, while only one-fifth (21%) indicated “very little” or “not at all.” In fact, only 7% of students felt that the service-learning project did not contribute to their learning in the course.

Most of the survey questions were open-ended. It is here where we begin to develop a better understanding of how participating in a service learning project through CommUniverCity, regardless of academic discipline, really deepens a student’s understanding of “community” and the larger issue of social justice and equity.

Several students commented on the value they received from working on a real-world project and seeing a concrete impact from their work:

The most rewarding and enjoyable aspect was having the opportunity to make a difference with local residents. They mentioned how disenchanted they previously were with the planning process, but, for the first time, they now feel listened to. I loved interacting with such a diverse group of residents, all with different backgrounds and concerns. [Urban & Regional Planning Student, Spring 2012]

I think the most enjoyable part was going out to hear the community’s wants and needs. They had a lot to say and it seemed like they have the power to voice their opinion but feel like it’s a loss. It was moving to see them so troubled by it and how much a community is affected by the place they live. [Political Science Student, Fall 2012]

I learned that we are able to serve in many different ways…It may seem small to us…but being there talking to the parents of our future generations is a huge deal to the community. [Counselor Education Student, Fall 2012]

Another outcome of participating in the service-learning project was the stated desire among many of the students to become more involved with their own community:

I really appreciate the opportunity to be able to…work in my community and I hope to contribute doing so in the near future. [Mexican American Studies Student, Spring 2012]

I really have a desire to work with my community. [Justice Studies Student, Spring 2012]

I should get more involved in the community I live in. I don’t want to be the guy that didn’t contribute to making my community better. [Political Science Student, Fall 2012]

Merging the University with…community service is a wonderful way to open the eyes of young adults to the importance of being involved in the community. [Nutrition & Food Sciences, Spring 2012]

These responses provided a preliminary glimpse into what research suggests is a long-term benefit of service learning experiences—increased civic engagement (Astin et al., 2006).

Students were asked to identify the most challenging aspect of working on the CommUniverCity project. Given the large percentage of working students and commuter students at SJSU, it wasn’t surprising that several students commented on the amount of time required for the SL project and the difficulties of collaborating with other students outside of class and off-campus:

Carving out the time to spend on the project was the hardest aspect. I do not live in the area, work full time, and go to school full time so trying to find the extra time for the project was very difficult. [Urban & Regional Planning Student, Fall 2012]

Trying to balance out my hours with school, work, and commuting. [Education Student, Spring 2012]

Another concern voiced by students in several of the SL projects related to the challenge associated with the language barrier and working with the local community. For many residents in the CommUniverCity neighborhood, Spanish was the primary (and often, only) language spoken. This posed a unique challenge for SL courses where the emphasis was on building social capital and engaging with community members.

The language barrier, at times I felt confident in my Spanish, at times I did not. [Counselor Education Student, Fall 2012]

Preparing for the event. We presented to a Spanish speaking organization, so preparing the presentation was challenging since we were trying to do it in Spanish. [Business Student, Fall 2012]

The most challenging part of the project was the fact that [the community members] did not speak English. [Business Student, Spring 2012]

Conclusion

The impact of campus-community SL partnerships on service-learners, the community, and local government partners was manifold. Students learned directly from the residents’ deep understanding of their neighborhood, the community benefits when students put their specialized skills and knowledge in action to address community priorities, and community-based and local government agencies greatly leveraged their work in the communities they serve.

SL partnerships also serve as a vehicle for disciplines across the board to engage directly in sustainability in ways that both have a positive impact on students’ engagement with learning, and also generate tangible physical and social change in the community. When carefully balancing the three cornerstones of equity, economics and the environment, sustainability can provide a unifying framework that brings together wildly diverse aspects of community change. Thus, the goals of promoting long lasting, deep learning among students and advancing community priorities under a comprehensive framework can be met by integrating community-based experiential learning in sustainability education.

Our experience in CommUniverCity indicates that, for SL sustainability partnerships to thrive and be sustained over time, two key conditions must be in place:

- A long-term outlook. In central San Jose, it has taken over 7 years for evidence of community change to begin emerging. It takes time for partners to develop some trust that everyone will stay with the relationship despite obstacles or difficulties that will surely arise.

- A strong commitment to sustaining cross-sector and interdisciplinary partnerships. Sustainability, particularly in the context of neighborhood change, is not the domain of a single discipline or sector, as it entails work of great complexity. In CommUniverCity’s case, a strong multi-sector commitment that engages academia, local government, the nonprofit sector, businesses, and grassroots organizations has been instrumental in sustaining this effort over time. However, maintaining close multisector and interdisciplinary ties is not without challenges, emerging from shifting and at times conflicting priorities, and greatly different institutional and disciplinary cultures. Working out of a shared context, stakeholders are constantly reminded that institutional power is both a resource and a challenge.

While the promises of SL partnerships in sustainability are abundant, there were also challenges along the way, particularly for institutions of higher education such as SJSU with a significant number of working students, where the substantial commitment of time and attention that authentic, impactful community work entails may clash with students’ family and work responsibilities. Faculty and students must also be prepared to navigate the challenges of interacting with highly diverse communities in their own terms (by, for instance, accommodating diverse language abilities and needs such as childcare and demanding schedules).

Ultimately, however, these are challenges worth meeting. Through sustained, active engagement, SL sustainability partnerships have the potential of transforming the individuals who participate, partner organizations, and the communities in which they operate.

Endnotes

[1] An excellent history of CommUniverCity can be found in Christensen & Jackson, 2009.

2 In fact, for the first five years, CommUniverCity focused exclusively in one neighborhood within Central San José, Five Wounds/Brookwood Terrace.

Bibliography

Astin, A. W., L. J. Vogelgesang, K. Misa, J. Anderson, N. Denson, U. Jayakumar, V. Saenz, & E. Yamamura. (2006). Understanding the Effects of Service-Learning: A Study of Students and Faculty. Higher Education Research Institute, Graduate School of Education and Information Studies, University of California, Los Angeles.

Briggs, J. (n.d.). Longitudinal Analysis: Comparing SJSU to Other Institutions Using NSSE Data, Essential Learning Outcomes, and High-Impact Practices from 2002-2011. Office of Institutional Research, San José State University.

Brundiers, K., A. Wiek, & C. L. Redman. (2010). Real-world learning opportunities in sustainability: From classroom into the real world. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 11(4): 308-324.

Christensen, T. & M. Jackson. (2009). CommUniverCity: Building a partnership for service and learning. In Civic Service: Service-learning with State and Local Government Partners, eds. D. P. Redlawsk, T. Rice and Associates. (San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.).

Rowe, D. (2007). Education for a sustainable Future. Science, 317(5836): 323-324.

San José State University. (2011). Mission. Available at: http://www.sjsu.edu/about_sjsu/mission/ (accessed January 24, 2013).

Seifer, S.D. (1998). Service-learning: Community-campus partnership for health professions education. Academic Medicine, 73(3): 273-277.

U.S. Census Bureau. Census 2010, Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics. Generated by Hilary Nixon, using American FactFinder; http://factfinder2.census.gov (accessed January 10, 2013).

Hilary Nixon is an Associate Professor in the Department of Urban & Regional Planning at San José State University. She specializes in environmental and community-based planning. She currently sits on the University Sustainability Board and has focused her teaching on community-based experiential learning since 2006. In addition, Dr. Nixon is a Research Associate with the Mineta Transportation Institute, where her research focuses on sustainable transportation. She can be contacted directly at hilary.nixon@sjsu.edu.

Hilary Nixon is an Associate Professor in the Department of Urban & Regional Planning at San José State University. She specializes in environmental and community-based planning. She currently sits on the University Sustainability Board and has focused her teaching on community-based experiential learning since 2006. In addition, Dr. Nixon is a Research Associate with the Mineta Transportation Institute, where her research focuses on sustainable transportation. She can be contacted directly at hilary.nixon@sjsu.edu.  Dayana Salazar is a Professor in the Department of Urban & Regional Planning at San José State University and Executive Director of CommUniverCity, a service-learning partnership between the local community, San José State University, and the City of San José. In 2012, she was awarded the university’s Distinguished Service Award for her working serving the campus community, providing hands-on training for students, and building a solid infrastructure between the university and surrounding community. She can be contacted directly at dayana.salazar@sjsu.edu.

Dayana Salazar is a Professor in the Department of Urban & Regional Planning at San José State University and Executive Director of CommUniverCity, a service-learning partnership between the local community, San José State University, and the City of San José. In 2012, she was awarded the university’s Distinguished Service Award for her working serving the campus community, providing hands-on training for students, and building a solid infrastructure between the university and surrounding community. She can be contacted directly at dayana.salazar@sjsu.edu.