Ancient Wisdom, Modern Times: Decolonizing Education Paradigms in a Southwestern Tribal Community

Link to Table of Contents: March 2018, Decolonization Issue

Cannon JSE March 2018 Decolonization Issue PDF

Abstract: For millennia, education for the Hualapai Tribal people was learned through intergenerational lessons taught with the family. This provided younger generations with the skills and knowledge needed to thrive in harsh desert environments. Over the past centuries tribal education has undergone numerous transitions. For the past twelve years the Hualapai Ethnobotany Youth Project has implemented an intergenerational learning program with the elders and youth of the tribal community to instill the centuries old knowledge that could only have been obtained through generations of experience. The program looks to new ways in modern times to teach the old ways in maintaining the continuity of knowledge that only the grandparents can remember.

Keywords: Hualapai, Ethnobotany, Bilingual, Arizona, Grand Canyon, Culture

To the untrained observer traveling the landscape of Northwestern Arizona, the land may appear dry, desolate, and devoid of life. The Hualapai people, however, know the true bounty locked inside the dry desert façade. An ongoing ethnobotanical project in the Hualapai community in northwestern Arizona is providing structured and consistent methods where elders can share their knowledge of plants and land in English and in their heritage language to tribal youth. Through field trips and classroom-based teaching, participants are using modern teaching practices alongside ancient traditional ways of knowing.

Hualapai formal education over the last 100 plus years has as many twists and turns as the course of the Colorado River itself, which comprises 108 miles of the reservation’s boundary. The Hualapai people are an Indian tribe native to the Southwest. Traditionally they organized themselves among 14 different tribal bands that each subsisted within their own territory encompassing a seven million acre region of Northwestern AZ from the south rim of the Grand Canyon and Colorado River, southward to the Bill Williams and Santa Maria Rivers. In 1871 after years of war with the U.S. Cavalry, the Hualapai were defeated and rounded up into a temporary reservation. By 1883 an official reservation was established for the tribe, one seventh the size of their ancestral land base. In 1901, an Indian boarding school was opened on the reservation. Assimilation was a policy adopted by the U.S. government which intended to absorb Native Americans into mainstream American Life.

These assimilation policies developed shortly following the Indian wars when Native Americans were no longer deemed a threat to non-Native peoples. In 1892, Congress passed the Appropriations Act which made Indian education compulsory. Indian children were rounded up and forced to attend Indian boarding schools away from their families where they learned reading, writing, arithmetic, and trade skills in the English language to become “productive American citizens.”

Hualapai children at the Truxton Canon boarding school. Children attended from 1901 to 1937. Credit: Hualapai Department of Cultural Resources Department

During this era, the federal government’s approach to education was to strip Indian children of their culture and heritage so they could become acculturated into white society. English was mandatory and the Hualapai language was forbidden to be spoken.

Some half a century later, in the fall of 1975, Hualapai Indian children were subject to a second round of assimilation, only this time in the reverse order! Children that attended the Peach Springs Bilingual/Bicultural School from 1975-2000 were taught Hualapai language, culture, ethnobotany, zoology, and ethnogeography.

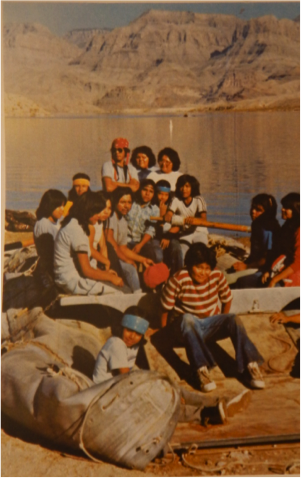

Photograph of students and staff on a Bilingual School Program River Trip outing down the Colorado River. Photo Courtesy HDCR Library.

In pre-contact times the Hualapai survived off of seasonally available wild plants and animals, and farmed where adequate water resources were available. They had elaborate trade networks with surrounding Tribes including the Mojave, Havasupai, Hopi, and Paiute, with their trade goods reaching as far as the Pacific Ocean to the west and the Rio Grande valley to the east (Stein 2002).

When the Bilingual School was founded, the Hualapai team of teachers that developed the curriculum had the forethought to teach what was relevant from the Hualapai perspective. In large part, this involved teaching the ethnobotanical knowledge. Initial Hualapai efforts at formal language development and maintenance began at the Peach Springs Elementary Public School, which instituted the Hualapai Bilingual Bicultural Program in 1978 (Funded by the Title VII, Bilingual Education Act).

The Hualapai Bilingual/Bicultural Education Program was initiated in 1975 when Japanese linguist, Akira Yamamoto, began to learn and document the Hualapai language and culture. In doing so he also created curriculum materials that could be utilized to ensure children could maintain their heritage language (Watahomigie & Yamamoto, 1987). The program initiated with a three-year grant from Title VII, the Bilingual Education Act, to develop an orthography, a dictionary, as well as instructional materials in Hualapai. In the three years that followed, (1978-1980) the Hualapai Social Studies Curriculum Guide, a Language Arts Curriculum Guide, the Hualapai Reference Grammar and publications about the local area were produced and staff training was provided.

During the first workshop, participants were involved in identifying Hualapai characteristic ways of teaching and learning. These then became the foundation for the later development of curricula, materials, identified educational goals, the school’s philosophy, as well as instructional practices (Watahomigie & McCarty, 1994). In addition, community needs assessments were conducted to ensure feedback was taken into consideration. Parents as well as tribal elders were asked to evaluate the program and include their own viewpoints on education. The more the program was able to develop, community support grew.

The curriculum and instructional content of the Bilingual program was presented in both English and Hualapai. A concurrent approach to bilingual education was utilized whereby central concepts, vocabulary, language patterns and skills were intended to be developed and reinforced in English and the heritage language (University of Washington Center for Multicultural Education).

In addition to instituting the Hualapai language in the school setting, this nationally acclaimed program developed a Hualapai orthography and instructional units, which paralleled the content of the standard English-only curriculum. Bilingual curriculum books were developed to be culturally relevant and taught about the local flora, fauna, geography, land sites, and the meanings of petroglyphs and pictographs within ancestral tribal lands.

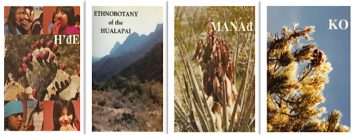

Sample of Bilingual School Curriculum Books, left to right H’de (Prickly Pear Cactus), Hualapai Ethnobotany, Manad (Banana Yucca), and Ko’ (Pinon Nut). Photos Courtesy HDCR Library.

Field trips and hands on activities were a regular component to the Bilingual School. Former attendee and Hualapai Tribal member Pearl Sullivan had fond memories of these outings. She shared that “They took us to all the rock writing sites and we got to learn all about our land, that was the best part, getting out and doing things, not just random things either, things that pertain to who we are as Hualapai” (Sullivan Personal Communication, 2018).

The Hualapai Bilingual Program in the Peach Springs Elementary School was cut in the 1990’s after a gradual decline due to the lack of support as the school went through significant leadership and directional changes. It should be noted that the new leadership at the school was non Hualapai and lacked Hualapai tribal support. This also coincided with proposition 203 English Only legislation that passed in the State of Arizona in 2000.

When the Bilingual School discontinued in Peach Springs, there was no longer formal programming to transmit the language, ethnobotany, and land based knowledge to youth.

It has only been approximately 140 years since Hualapai people were living entirely off the land. Even after Hualapai tribal members were forced to take up wage labor employment beginning in the late 1880’s it was not uncommon for members of households to continue many traditional subsistence practices to supplement livelihoods well into the 20th century.

The “Hualapai Ethnobotany Youth Project” arose as elders of the community expressed concern that many youth were not learning about their landscape. Hualapai elders began to acknowledge and discuss that ethnobotanical knowledge was in grave danger of fading away if not passed on to the next generation. Jorigine Paya, one of the elder instructors of the Project has shared her memories with youth participants: “I remember when growing up with my paternal grandparents, we harvested a lot of the traditional food plants such as the prickly pear, mescal, banana yucca, sumac berries, and the Indian tea. We prepared it in different ways depending on the plant, or if it was in the form where it was ripe, and ready for harvest, we ate it right there as it was. For the mesquite beans we would gather a lot to where we would make flour, also we made dumplings in boiled water from rolled balls of mesquite bean flour. And we would eat these foods, and never did we have a problem with diabetes” (Paya Personal Communication 2015).

Hualapai elder instructor Jorigine Paya harvesting Indian tea on a Hualapai Ethnobotany Youth Project field trip. Photo by Carrie Cannon

The purpose of the Hualapai Ethnobotany Youth Project is to share in the transmission of ethnobotanical knowledge with community tribal members, while promoting knowledge of traditional harvesting practices and the Hualapai language. All of the elder instructors of the project are fluent Hualapai speakers. They teach the youth the tribal names of the plants, which often describe something about the plant. Elder instructor Lucille Watahomigie uses repetition to teach the youth the plant names, “Aha, repeat it again, Aha, this is the name for the Cottonwood; “Ha” meaning water indicates this plant is named for the knowledge that it grows by the water.” On a trip into Peach Springs Canyon, within the Grand Canyon, Lucille points to the cattail, “Hamsi’iv, Hamsi’iv, say it again, this name has the word Hamsi’ in it, meaning “star.” When that cattail goes to seed, and the fluffy seeds drift away on a breeze, look at the shape, it resembles a star,” she tells the participants.

Today, the majority of Tribal members live on the reservation in the capital town of Peach Springs, and have little time in the modern world to travel and harvest the traditional foods. This makes teaching the traditional ways difficult for most families, especially since many of the bands are removed from their ancestral lands. Today the Tribe relies upon tribal elders to share knowledge to youth through intergenerational classes facilitated by the Hualapai Department of Cultural Resources (HDCR).

The Hualapai Ethnobotany Youth Project is an intergenerational program designed to provide elders with an opportunity to share their plant and land based knowledge with Hualapai youth. After school and on weekends, for a few hours a week, the cell phones, TVs, and text messaging are dialed down, and the focus is brought back to the land- to an ancient knowledge, to a tribal technology that served the Hualapai for hundreds of generations, and which brought power and life to the people.

HDCR Staff member Drake Havatone in the center with Hualapai Ethnobotany Youth Project participants wearing their Cliffrose bark vest and skirt, from left to right, Spirit Wolf Havatone, Lone Wolf Havatone, Spring Havatone, and Running Wolf Havatone. Photo by Carrie Cannon

Since the Hualapai Ethnobotany Youth project began in 2006, students have been involved in harvesting many plants including the mescal agave, wild turnip, cholla cactus buds, sumac berries, wild grapes, banana yucca fruit, prickly pear, mesquite beans, and piñon nuts. Twice a month down at the Hualapai Cultural Center between 15-30 tribal youth ranging in age from 7 to 15, meet with the 5 elder instructors. Activities include a full day field trip followed later in the month by a class session at the Cultural Center where students learn how to prepare what they have harvested for consumption or craft. On the field trips, students learn the plant identification, growing habitats, harvesting season, uses for medicinal, dietary, or utilitarian purposes, and Hualapai and English plant names. The plants are harvested when seasonally available and used for demonstrations in food preparation, basketry making, cradleboard construction, and making of traditional garb such as the cliffrose bark skirt and shirt.

In 2013, the idea was presented to gather multiple species of the mescal agave, as would have been done in ancestral times. Students continued the accustomed practice of harvesting Agave utahensis on the Reservation within Peach Springs Canyon, a side Canyon within the greater Grand Canyon. Then students went on a field trip to Lake Havasu, AZ to visit an archeological mescal agave pit roasting site as part of a joint effort with the Bureau of Land Management staff. Here they gathered Agave mckelvyana. Later as the season progressed Agave parryi was harvested outside of Seligman, AZ and the Native American Club from the local Kingman High School came along to learn from the Hualapai Ethnobotany Youth Project. At the annual Pai Language Immersion Camp held on the reservation, the Hualapai Ethnobotany Youth had the chance to roast the 3 different species and compare and contrast the taste and texture.

Ethnobotany elder instructor Frank Mapatis harvesting mescal agave with Ethnobotany Youth Project participant, Phyna Cook in Peach Springs Canyon, Hualapai Reservation. Photo by Carrie Cannon

Transferring ethnobotanical knowledge takes time. It is an all day effort to harvest enough mescal agave to do a traditional roast. When you talk to a Tribal elder they will tell you, “you don’t just harvest it and you’re done.” After you pry the agave rosettes from the ground, you take it back to the community and it is another day long effort to remove all the green thorny leaves to prepare the agave hearts for roasting. Then you prepare the pit, gather the rocks, the juniper wood, the barrel cactus that you de-thorn, slice, and place in the pit. When the fire is lit, and all the coals have burned down, the mescal is placed in the earthen oven and buried over night; it is unearthed the very next day with great anticipation. Students and elders of the ethnobotany project are involved in each stage of this process. The effort is rewarded with a taste of sweet, juicy, calcium-rich roasted mescal that has a flavor like nothing else in the world. In each stage of the process, the elders speak in the tribal language, they say prayers, and they instruct tribal youth on the traditional tribal philosophies.

Photos of Ethnobotany Project elders and youth participants processing mescal agave and barrel cactus, and preparing the roasting pit for the 24 hour traditional mescal agave roast. Photos by Carrie Cannon

Altitudes within the ancestral Hualapai territory range between 2,000 and 7,000 ft. This wide range of elevations contains a diverse landscape with rivers, springs, canyons, cliffs, flats, valleys, mountains, and desert. As a result of the tremendous diversity in the landscape, a great variety of plants were available throughout the year encompassing both Mojave and Sonoran Desert species.

Hualapais subsisted through hunting, small scale agriculture where water was available, and through gathering seasonally available plant resources. The traditional subsistence lifestyle followed an annual sequence of resource use and movement focused on several key plant foods. This included a concentrated effort on a mescal agave harvest in the spring, as well as wild onions, turnips, and cholla buds. Following the mescal agave harvest, families and large camps moved to basin floors to gather several different grass-like species which provided seeds rich in protein and carbohydrates. By midsummer, fruits of several cacti species ripened and Hualapai camps shifted back into the canyons and foot hills. Late summer and early fall provided mesquite bean pods and banana yucca fruits, and efforts were also devoted to nut and berry gathering including the piñon.

Ethnobotany Project instructor and Tribal elder Malinda Powskey came from the last family from the Big Sandy River Band still living off the land and maintaining many of the old ways. “I am a member of the Big Sandy River Band of Hualapai. My family came from the last member of that Band to still live down there. When we teach the plants to the children we also teach them the place names in the Hualapai language, ‘Wikman’ that is Valentine AZ, meaning Falling Rocks, ‘Ivthi Gatanavkwa’ is Kingman, that means Surrounded by Creosote, and there is ‘Hakdagwiva’ the name for Peach Springs, meaning Surrounded by Springs, and ‘Hak Skela,’ today that’s the Big Sandy River, it means ‘The Open Water.’ If our children lose the knowledge of place names, they lose part of their history, where they come from. In the teaching of the ethnobotany to the children we had in mind to teach those places to our children too, because the plants are not just separate entities, they are part of the land just like the people” (Malinda Powskey, Personal Communication).

The Big Sandy River lies within the southernmost reaches of ancestral Hualapai territory extending into the northern stretch of the Sonoran desert, in the vicinity of present day Wikieup, AZ. Raised in this region, Malinda remembered harvesting the sweet ripe fruit of the Saguaro cactus in June. Long wooden poles were lashed together to make an “i:isiqlab” or a Saguaro knocking pole used to tap the fruit down from the tall cacti. The fruit can be eaten fresh, seeds and all, or the juice and seeds separated to yield a festive beverage. In the autumn, Malinda helped her family harvest traditional garden crops of corn, beans, and squash yielded from gardens irrigated by the river. In the spring time the mescal agave flower stalks began to emerge and were ready for harvest. As a young girl she learned from her family the way to pry the agave from the ground, and cut off the spiny green leaves to yield the white colored heart which is then roasted in an earthen oven. Now, as an instructor, she shares with the Ethnobotany Youth Project the precise manner in which to roast the agave. Stones are placed in the four directions of the roasting pit representing the cardinal directions, and the youngest child present that was born in the summer time is selected to light the fire to ensure the agave burns nice and hot.

Ethnobotany elder instructor Malinda Powskey hiking in the Grand Canyon sharing Ethnobotany. Photo by Carrie Cannon

When we had students fill out a survey to gauge their feelings about what they were learning, several comments indicated the students have taken an increased interest in learning their language. One student commented, “This program is a very cool program. If it wasn’t for this I would not even be interested in my language.” Another student responded, “I like being in the Ethnobotany class because it helps me learn more Hualapai words.” Besides language, students have been grateful for the knowledge they have gained. One student commented on her survey, “I just want to say this project is a very good way to teach youth about our heritage and plants in the Hualapai way.”

Down in Phoenix, at the Heard Museum, a lengthy applause develops, echoing through the reception room as Malinda Powskey receives the 2015 “Arizona Indian Living Treasures Award.” Malinda received this honor for her lifetime of achievements in promoting tribal language, culture, and ethnobotany. She is one of four recipients from various Tribes throughout the state to accept this prestigious award. The dedicated effort and time elders like Malinda have contributed to the Hualapai Ethnobotany Youth Project is greatly appreciated and has served to pass the Hualapai culture to the present and future generations. She is one of the last remaining links to the past and her knowledge of the old ways persists due to her contributions.

Malinda Powskey receiving the prestigious Arizona Living Treasures Award in 2015 for her contributions in ethnobotany, language, and cultural preservation. Photo by Carrie Cannon

Bibliography

McCarty, T. L. (1994). Bilingual education policy and the empowerment of American Indian communities. The Journal of Educational Issues of Language Minority Students, 14, 23-41.

Stein, Pat H. (2002) School Days at Truxton Canyon. Arizona Preservation Consultants, Flagstaff, AZ.

University of Washington Center for Multicultural Education. The Hualapai Bilingual/Bicultural Education Program (HBBEP). https://education.uw.edu/cme/hualapi.

Watahomigie, L. J., & McCarty, T. L. (1994). Bilingual/Bicultural education at Peach Springs: A Hualapai way of schooling. Peabody Journal of Education, 69(2), 26-42.

Watahomigie, L. J. & Yamamoto, A. Y. (1992). Local reactions to language decline. Language: Journal of the linguistic society of America, 68(1), 10-17.

Carrie Calisay Cannon is a member of the Kiowa Tribe of Oklahoma. She has a B.S. in Wildlife Biology and an M.S. in Resource management. If you wish to contact her you’ll need a fast pony to catch up with her and Thundercloud as she travels Arizona lands promoting the persistence of ethnobotanical knowledge to endure as a living practice and tradition. You can reach her at calisay17@hotmail.com.

Carrie Calisay Cannon is a member of the Kiowa Tribe of Oklahoma. She has a B.S. in Wildlife Biology and an M.S. in Resource management. If you wish to contact her you’ll need a fast pony to catch up with her and Thundercloud as she travels Arizona lands promoting the persistence of ethnobotanical knowledge to endure as a living practice and tradition. You can reach her at calisay17@hotmail.com.