Silver Linings: A Phenomenology of Hope and Purpose in Climate Change and Sustainability Education

Abstract: Hope is a human process of discovery and perseverance that is based in personal values, a vision of the future, and a sense of purpose. This essay gives a brief overview on the role of phenomenological research in discovering the meaning of people’s lived experiences, such as the experience of hope. An example of phenomenological research on field ecologists’ lived experiences of climate change is provided in order to illuminate the experience of “silver linings” as the experience of hope while living in the midst of the dark cloud of climate change. An overview of a reflective curricular activity designed to cultivate hope and purpose in sustainability studies is provided.

Keywords: climate change, ecologists, education, hope, lived experiences, phenomenology, purpose, sustainability

Silver Linings: A Phenomenology of Hope and Purpose in Climate Change and Sustainability Education

INTRODUCTION

I’ve been thinking about the meaning of ‘hope’ for almost 20 years. It was a November afternoon in 1997 and I was preparing a speech I would give the next day. My goal was to start a new sustainability education organization in Colorado. The purpose of my speech was to convince a grant-making board of directors that the new sustainability education programs would benefit our community and be an excellent investment of their philanthropic funds.

I began the first trial run of my speech. A friend of mine, who had more experience in sales and marketing, was there to give me feedback. Two minutes into the speech I was explaining the new organization’s program goals. “We hope to serve 1,000 students in the first year.” Suddenly my friend stood up with her hands in the air. “STOP! Don’t use the word hope! It’s too wishy-washy. They won’t take you seriously.” I was dumbfounded by her feedback. My personal values, professional training, life purpose, and vision for the future were all focused on the creation of this new sustainability education organization. I felt demoralized that the word “hope” would be perceived as emotional fluff. My friend coached me, and suggested I use the word “goal” or “impact” instead of “hope” and that those more concrete words would imply I had done my due diligence planning and had my act together. I didn’t disagree with my friend but from that day on I’ve continued to wonder about the meaning of hope.

Over the years since that November afternoon, as the founder of an organization with a mission to “awaken a sense of wonder and inspire environmental stewardship and sustainability through natural science education,” I’ve had to muster up a good deal of hope and overcome challenges along the way. The first five years running the organization were difficult. Raising money, managing employees, creating plans, marketing programs, developing partnerships, and building the board of directors, seemed to take all of my waking hours. But I persevered. I had a strong sense of purpose. I stuck to what I valued, I tapped into my inner strengths, I held a vision of the future organization, and I never wavered in my belief that it would happen. This was the formula that fostered my hope.

I’ve continued to consider the sources of my hope, and how my ideas and actions may inspire hope in others. You could say hope has become the keystone of my reflective practice. I’ve filled the pages of my journals with reflections on hopeful visions and my journeys along the way. More recently as a Ph.D. student focusing on the human dimensions of climate change and conservation psychology, I conducted phenomenological research with place-based ecologists who research climate change in mountains of the American West (Langmaid, 2009). I wanted to understand how these ecologists sustained their own sense of hope, and persevered in their careers; while coping with the complexities and political strife related to climate change in the institutions they work for. I share my research in this essay because I believe my findings hold examples of hope and purpose in the lived experiences of a group of people who are intimately connected to the places and species they study; perhaps, akin to many sustainability educators. These ecologists experienced a sense of loss and despair while maintaining hope and a fervent commitment to their long-term research. They are committed to sharing their scientific discoveries with wider audiences to help promote more sustainable futures.

In the remainder of this essay: 1) I briefly describe the role of phenomenology in understanding people’s lived experiences; 2) I provide a glimpse into my research on ecologists’ lived experiences of climate change—specifically one phenomenological theme from my research that reveals the inherent creative tension in hope—a theme I named “silver linings”; 4) Finally, I briefly provide an overview of a reflective curricular activity I use to cultivate hope and purpose in undergraduate sustainability students. My hope in writing this essay is that sustainability educators, students, and others will draw upon some of these insights to cultivate even more hope in their own lives.

THE ROLE OF PHENOMENOLOGY

With its emphasis on seeking meaning through a rigorous process of analyzing human experience, phenomenology is used to investigate acts of consciousness that are not readily available through natural science methods. If we think about ourselves as inherently meaning-making beings who are always in relationship with one another and the phenomena around us, then we are predisposed toward more conscious, thoughtful, and caring relations with others.

Human-environment researcher and phenomenologist David Seamon (2000) defines phenomenology as “the exploration and description of phenomena, where phenomena refer to things or experiences as human beings experience them…the aim is to use…descriptions as a groundstone from which to discover underlying commonalities that mark the essential core of the phenomenon” (pp. 158-159). Phenomenological studies inquire about the nature of people’s perceptions, imaginations, reflections and interpretations of phenomena. The phenomenologist thinks critically about the nature of our human existence.

Because phenomenology strives to develop precise descriptions of phenomena (things) as they present themselves in human experience, the phenomenologist sets aside her scientifically-based theories and abstract mental models. The phenomenologist describes “what is” and in the process comes to know herself in more meaningful ways. Rehorick and Bentz (2009) refer to this process as “transformative phenomenology” and explain “phenomenology provides a philosophical and practical framework for cultivating wisdom by challenging researchers and practitioners to look deeply into their subject matter and themselves” (p. 24).

Phenomenology is sometimes criticized for being too narrowly focused on individual experiences and for generating overly simplistic descriptions that don’t address the complexities of people and societies. Some critics have also claimed that phenomenology does not consider class or gender, that it uses nostalgia as data, and is far too mystical in nature. But there are numerous examples where phenomenology has been used as a tool for cultural analysis and understanding. Phenomenology is not appropriate for every kind of inquiry. It does not try to reveal causal relationships or correlations. Phenomenological human science researchers study people’s lived experiences. The term “lived experience” hold significance. The aim is to “explore directly the originary, or prereflective dimensions of human existence: life as we live it” (Van Manen, 2014, p. 39), The phenomenologist aims to see and describe the structure of human experiences such as: the lived experience of hope, of climate change, or of being a sustainability educator.

SILVER LININGS

The phrase ‘silver linings’ illuminates the meaning of hope; for hope does not exist without its counterpart, the dark cloud of despair. ‘Silver linings’ is the name of one of the experiential themes I discovered during my research with ecologists. The phrase was spoken by one of my research participants referring to his lived experience of climate change. I see his use of this term as a way of conveying the inherent creative tension within the lived experience of hope while working amidst the dark clouds of climate change.

As a sustainability educator confronted with teaching about climate change and concerned about the fate of my local home place and the greater earth, I initiated my research with ecologists because I wanted to understand how others engaged in learning and teaching about climate change were experiencing the phenomenon on a personal psychological level. I wanted to understand how they sustain hope and purpose in the face of adversity, knowing that the earth is changing in dramatic and unpredictable ways.

I determined to explore the lived experiences of place-based field ecologists who dedicate themselves, in large part, to understanding how earth’s species and ecological systems are changing. Ecologists view humans as integral to earth’s systems and they are able to convey both scientific and personal perspectives on their lived experiences. My hope was that a deeper phenomenological understanding of how field ecologists observe, experience, and respond to climate change would help me in my own efforts to productively educate and communicate about climate change in more personal and place-based ways than traditionally found in the academic literature.

Understanding how people perceive and respond to climate change is a complex issue that calls for innovation in social research, communication and education. My phenomenological research complements other social science about the role of experience, affect, and imagery in elevating people’s perceptions of the risks of climate change (Leiserowitz, 2006). Although field ecologists are not a representative sample of the general public, a glimpse into their experiences may shed light on what is to come for others as climate change encroaches on people’s lives in more visible, tangible, and salient ways.

I used a purposeful criterion sampling strategy and conducted phenomenological interviews with 20 ecologists whose research documents the effects of climate change in mountains of the American West. My analysis of the interview transcripts revealed eight experiential themes. In this section of the essay I focus on the theme “silver linings.” (Other themes include: thinking ecologically, place-based ecologist, seeing shifts, coping with complexity, paleo-perspective, crossing thresholds, and triage.) Below, I briefly interpret elements within the theme ‘silver linings’ and I provide exemplary quotes from ecologists.

My research participants have intimate first-hand long-term relationships with the places they study. When these places change, and the organisms that live there begin to decline, the ecologists’ experience a sense of loss, and in some cases, despair. Some ecologists expressed that they “have come to love the place” where they’ve spent so many years. They expressed how “it would hurt to leave this place.” One ecologist who studies forests said:

As human beings, we get feelings. We get nostalgic about things and attached to the landscape. We attribute value to the landscape in various ways…A lot of the biggest and oldest trees are dying. There is a part of me that is saddened because I like big old trees on the landscape…But this is also an interesting scientific phenomenon with important implications…There’s another part of you that, you know…Well anyway, I’ve lost a lot of trees that I considered friends, that I paid attention to, and they have died.

Despite lack of funding for their research to continue uninterrupted without gaps in ecological data they collect, many ecologists have made personal commitments to sustain their long-term studies. Many of them consider their long-term data their most important contribution to science and society. A sense of agency and commitment to their work is born of their values for the places and species they study and have come to love.

Once you’ve been in a place long enough you come to notice these things happening…They are your friends, and your friends are gone, and this is a very disturbing shock…I actually started to get depressed…I was facing the loss of things I valued in this place.

I am not an advocate telling the world how to manage mountains. I am providing information that I hope society, as a whole, will take to manage the mountains sustainably so future generations can enjoy them.

I keep having to remind myself of the unusualness of the things we’re seeing. Intellectually, I see and understand it. But at a deeper level, it’s hard to accept…Actually it’s disturbing; and it’s worrisome…It’s an honor and a privilege to be involved in recognizing what’s going on…It’s also disturbing…It’s an extreme and extraordinary change…It’s scary…It’s the largest challenge facing us as a society…It’s going to require that scientists and policy makers…And all of us become more committed to communicating better.

Some ecologists grapple with the deeper personal philosophical dimensions of their scientific discoveries. They practice scientific objectivity within a human emotional landscape. They see the impacts of climate change happening within a much larger evolutionary time scale. This longer-term sense of evolutionary time can also bring a sense of hope.

I have an epi-level of hope. By bringing knowledge of [the earth’s] dynamism, humans can live in more accord with their natural and cultural environment and be more at peace with themselves and constitute ourselves more responsibly…It’s far more important to me that we learn to live in relationship with those natural processes.

I’m pretty pessimistic these days…Gloomy about an apocalyptic event…But if we can act locally…And collectively…We can try and do things sustainably…There are hopeful lessons…We have to move forward…It’s not just about going back to the past; it’s about learning how to adapt to the unusual things we’re seeing today that are really extraordinary.

I’m feeling a little upbeat in that we can deal with the changes…At least as long as we accept change…Novel ecosystems are not only inevitable; they’re already here…Once you’ve decided that change is inevitable and expect it, then maybe you’re better prepared to deal with it.

Some ecologists express their work like that of a “doctor” trying to save lives. Despite the fact they will lose some of their patients, they remain committed to saving the lives of those who have the greatest chances of survival. They experience their work as “triage” and they maintain their sense of hope and agency in relationship with those whom they are working to save.

The analogy is that our bodies are at 98.6 degrees and only an extra degree gives us a fever. Only three or four degrees can be fatal either way…It’s not about the actual degree; it’s about the average temperature that allows all this processes to occur.

You’re trying to figure it out, and you’re trying to document it. You’re trying to start looking at solutions and how to adapt, and you’re busy; you’re busy dealing with the problem. You don’t really have time to dwell on it strictly in a negative sense.

I see myself as being an oncologist for the planet. I see that we cannot save everything, and we have got to start working on triage…We, right now, are standing at the edge of the sixth mass extinction of species on the planet, and it is being caused by us…When you’re just dealing with those animals that are right in front of your nose, you’re triaging others because they’re not right in front of your nose. You don’t have the money, the time, the energy, the effort to deal with them…We work as hard as we can; just like an oncologist.

The ecologists also feel they are learning more about the earth at a faster rate than they ever have. They are also forced to collaborate and break down barriers between scientific disciplines. There is a sense that, in the end, climate change will bring us closer together as a human species.

Hurricanes, snowstorms, and droughts… People looking around the world and seeing all these big changes, and they know at some visceral level we’re all stuck on this little tiny pebble up in the Universe. It’s a bit of a humbling sense…We’re all bound together…The silver lining in this whole dark cloud of climate change is that we will be more truly global as a species through time…This is bringing us all together.

In the words of one ecologist, practicing science is like “pushing up against dogmas” and co-creating the way in which we know the world we are always in. The more the ecologists come to know about climate change, the more they are compelled to act. Although they may disagree about how to respond, they are still working for what they each believe can be a sustainable future. The world is changing and there are choices that need to be made. Hope and purpose can be born within the creative tension of climate change, working to make a contribution and develop sustainable futures.

I see the ecologists’ experiences of hope and purpose consistent with the philosopher Gabriel Marcel’s (2010) phenomenology of hope. Marcel suggests that humans are “travelers” always on our ways to somewhere or something, always in relationship, and conscious of time. In this way of seeing ourselves at travelers on a journey, hope lives within a creative process of self-development that is fueled by our souls, our values, and that which we “take to heart.” Hope is “a vital aspect of the very process by which an act of creation is accomplished” (p. 51). At the core or our hope is a sense of reciprocity with others, a consciousness of compassion and communion. “Hope aims at reunion, at recollection, at reconciliation: in that way, and in that way alone, it might be called a memory of the future” (p. 47). Purpose is spawned as deliberate intention to move forward. Purpose is the process, the adventure, the action kindled by the creative tension that exists between hope and despair.

CURRICULAR ACTIVITY TO CULTIVATE HOPE AND PURPOSE

Building off my phenomenological research, my teaching experiences as a sustainability educator, and my learning as a life-long student of leadership, I have developed a reflective curricular activity to cultivate hope and purpose (Langmaid, 2015). I use this activity in undergraduate sustainability leadership courses and with educators whom I mentor.

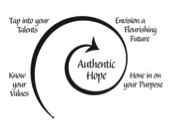

Through the activity, and its accompanying worksheet, students: 1) reflect on and explain their personal values and talents, 2) write a vision statement of a flourishing future, 3) synthesize their values, talents, and vision in a personal purpose statement, and 4) participate in a conversational student-centered workshop to work together on recognizing how a sense of purpose can lead to a more hope and purpose in one’s life.

Tilbury (2011) suggests sustainability education requires new pedagogical strategies and learning processes including “learning to clarify one’s own values” and “learning to envision more positive and sustainable futures” in order to participate in creating a more sustainable and hopeful world. I draw upon David Orr’s (2009) term “authentic hope.” “Authentic hope…is made of sterner stuff than optimism. It must be rooted in the truth as best we can see it, knowing that our vision is always partial. Hope requires the courage to reach farther, dig deeper, confront our limits and those of nature, and work harder” (pp. 184-185). Authentic hope, the kind of hope based on personal values, talents, positive visions of the future, and a sense purpose, can encourage feelings of agency and foster sustainable behaviors (Ojala, 2012). As students reflect and become more aware of their values, and take initiative to identify and apply their talents, they more readily formulate positive visions of their future, and activate their own embodied creative impulse to live sustainably and work toward sustainable futures in more purposeful and hopeful ways.

REFERENCES

Langmaid, K. L. (2009). Seeing shifts: Ecologists’ lived experiences of climate change in mountains of the American West. (Doctoral dissertation, Antioch University New England, 2009)

Langmaid, K.L. (2015). Discovering authentic hope: Learning and living with purpose. In Byrne, L. (ed.) Learner-centered teaching activities for environmental and sustainability studies. In revision.

Leiserowitz, A. (2006). Climate change risk perception and policy preferences: The role of affect, imagery and values. Climatic Change, 77. 45-72.

Marcel, G. (2010). Homo viator: Introduction to the metaphysic of hope. St. Augustine’s Press.

Ojala, M. (2012). Hope and climate change: The importance of hope for environmental engagement among young people. Environmental Education Research 18. 625-642.

Orr, D. (2009). Down to the wire: Confronting climate collapse. Oxford University Press.

Rehorick, D. A. & Bentz, V. M. (2008). Transformative phenomenology: Changing ourselves, lifeworlds, and professional practice. Lexington Books.

Seamon, D. (2000). A way of seeing people and place. In Theoretical perspectives in environment-behavior research (pp. 157-178). Springer US.

Tilbury, D. (2011). Education for sustainable development: An expert review of processes and learning. Paris, France: UNESCO. http://unesdoc. unesco. org/images/0019/001914/191442e. pdf. Accessed May, 20, 2014.

Van Manen, M. (2014). Phenomenology of practice: Meaning-giving methods in phenomenological research and writing (Vol. 13). Left Coast Press.

Kim Langmaid is an Adjunct Professor in the Sustainability Studies program at Colorado Mountain College. She is the Founder, Vice President and Director of Sustainability and Stewardship Programs at Walking Mountains Science Center in Avon, CO. Kim lives in Vail, CO and can be reached at kiml@walkingmountains.org.

Kim Langmaid is an Adjunct Professor in the Sustainability Studies program at Colorado Mountain College. She is the Founder, Vice President and Director of Sustainability and Stewardship Programs at Walking Mountains Science Center in Avon, CO. Kim lives in Vail, CO and can be reached at kiml@walkingmountains.org.