Regenerative Hope: Pedagogy of Action and Agency in the Learning Gardens

Williams JSE Nov 2015 Hope Issue PDF

Williams JSE Nov 2015 Hope Issue PDF

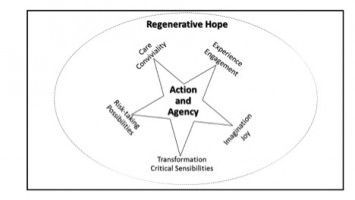

Abstract: Moving beyond the despair resulting from what appears to be a tipping point of life systems due to climate change, this narrative presents a possibility for regenerative hope. The article begins by discussing an emergent typology of hope that includes hokey hope, resolute hope, mythical hope, patient hope, hope deferred, sound hope, authentic hope, critical hope, and transformative hope. Drawing upon this typology, a model for regenerative hope is developed with the following features: care and conviviality, experience and engagement, imagination and joy, risk-taking and belief in possibilities, and critical sensibilities and transformation. Series of photos and voices of youth from a low-income middle school actively engaged in the learning gardens are presented as practical examples of pedagogy of action and agency manifested as regenerative hope.

Keywords: regenerative hope, learning gardens, garden-based learning, typology of hope, pedagogy of action and agency

Regenerative Hope:

Pedagogy of Action and Agency in the Learning Gardens

… What would it mean to live

in a city whose people were changing

each other’s despair into hope?

You yourself must change it.

What would it feel like to know

your country was changing?

You yourself must change it.

Though your life felt arduous

new and unmapped and strange

what would it mean to stand on the first

page of the end of despair?

Adrienne Rich (1983). Italics added.

I draw upon the urgings of Adrienne Rich above, as I explore my own commitment to address despair gazing me in the eye with the daily fearful bombardment of environmental/ climate news that is gloom and doom. As a long-time educator involved in urban school districts with school gardens to engage children and youth, I have found that my own down-to-earth experiences have enabled me to “stand on the first page of the end of despair”: despair that I have personally felt, sometimes, with the monumental social and environmental problems that are enmeshed into our lives; and despair that many urban school children, their families, their teachers, and their communities feel as they are often trapped in intergenerational poverty and subject to institutional and environmental racism. Yet, as I watch children and adolescents, along with their teachers and garden educators, in school gardens across dozens of school districts spanning various states, their collective soiled hands bring me hope and joy, even as I personally delight in seeding, growing, and harvesting both food and learnings. Engaged with the day-to-day nuances of life, whether it is the compost heaving with countless earthworms or the new seedlings emerging playfully and miraculously from soil, students across urban schools are learning academics in meaningful ways. In connecting with food and their bodies through the learning gardens, they simultaneously grow a sense of hope and develop a sense of agency. This requires sharpening and renewing skills to support the life-sustaining opportunities and regenerative possibilities that gardens uniquely offer.

Since I was enthused by the special call for papers for this journal, the notion of hope began to intrigue me. As we know, human beings tend to hope by extrapolating from evidence. Being a philosopher at heart and a gardener delighting in the practical richness of life taught daily by the garden, I began to reflect on what the concept of “hope” implies. By no means a complete conceptual analysis, I draw upon Berry (2010), Duncan-Andrade (2009), Freire (1997), hooks (2003), Orr (2011), Webb (2013), and West (2004; 2008) as I present in the first section an emergent typology of pedagogies of hope: hokey hope, resolute hope, mythical hope, patient hope, hope deferred, sound hope, authentic hope, critical hope, and transformative hope. Drawing upon this typology, I develop a conceptual model of pedagogy of regenerative hope that embodies experience and engagement, care and conviviality, risk-taking and belief in possibilities, critical sensibilities and transformation, and imagination and joy. In its manifestation, action and agency are companions to regenerative hope. In the second section, I explore how regenerative hope is revealed as young adolescents actively engage with the learning gardens at a school where I have conducted research for over a decade. The school has majority of students who live in poverty and are also from immigrant and/or refugee families, often dislocated and traumatized as they are uprooted from their culture and homes. Through active engagement, gardens provide opportunities for hopeful possibilities.

An Emergent Typology of Pedagogies of Hope

Hokey Hope, Resolute Hope

When we see dark clouds in the sky, we anticipate that the rains will arrive. If we are in drought stricken areas, though, we hope the rains will grace the land in a few hours, no matter the evidence that actually the clouds have been drifting away in a different direction. Impacted by drought, humans seek to lift themselves out of despair, hoping for rain. Duncan-Andrade (2009, p. 182) refers to such optimism regardless of evidence to the contrary as hokey hope. Working in resource-stricken, inequitable urban schools, he invokes Cornel West (2004, p. 296) to explain that an optimistic individual adopts the role of the spectator who, despite evidence pointing to different conclusions, infers that things are likely to get better. He laments that this “…hokey hope is peddled in urban schools all the time…[being] analogous to the individualistic up-by-your-bootstraps hyperbole that suggests if urban youth just work hard, pay attention, and play by the rules, then they will go to college and pursue the ‘American dream’” (p. 182). But the irony is that hokey hope ignores that middle-class opportunities and structures for success are not accessible for urban youth who are working-class and racial and ethnic minorities, he argues. That is, by disregarding the laundry-list of inequities, hokey hope does not account for the deep-rooted and structural societal unevenness of the playing field, he maintains. In a similar vein we find that while many urban schools across the country, especially those entrenched in poverty, offer free lunch to needy students, the nutritional value of that food is often not questioned. The hope of decreasing hunger trumps questioning the quality of food that inevitably impacts children’s health.

For Webb (2013), resolute hope would be close to this kind of hope. Drawing upon Pettit (2004) he writes, “Sometimes we hope against the evidence….Given that humans are emotional creatures subject to anxiety, grief and despondency in the face of brute fact, forming strategies on the basis of evidence-based calculations of ‘how things are’ would often lead us to despair” (pp. 406-407). Yet, in galvanizing human beings to overcome the burden of evidence to the contrary, a desired outcome through hope might seem more motivating. Indeed, there are some qualities worthy of individuals hoping resolutely: they tend to be more “energetic, outgoing, determined and less risk-averse” (Webb, 2013, p. 407), though this could also be seen as false optimism. For the resolute hoper, explains Webb, “agentic self-confidence means, firstly, that ambitious outcomes are more likely to be realised and secondly, that if they are not, hopeful energies will be directed toward different pathways or new goals” (p. 407). Can we act on the basis of resolute hope? Can a resolute hoper take chances? Indeed, states Webb (2013), if one hopes resolutely, then one is a “dogged anti-determinist,” “assuming that the world is fluid, plastic and capable of being moulded by one’s agency” (p. 407).

Webb concludes that resolute hope can be an individualistic, self-efficacious, private hope divorced from considerations of the wider social, economic and policy context: hoping against the odds (2013, p. 408). But when the playing field is not level, such resolute hope is indeed hokey hope as Duncan-Andrade points out. For new immigrant and refugee families in poverty, often uprooted from their agrarian roots, culture, and land, promises of some distant access to land to grow food in urban centers with long waiting lists might seem like hokey hope and resolute hope. Even though community gardens serve as more tangible alternatives, it is still often difficult for immigrant families and their children to be able to access them.

Mythical Hope

As a “profoundly ahistorical and depoliticized denial of suffering that is rooted in celebrating individual exceptions,” Duncan-Andrade (2009) reminds us that mythical hope is about a narrative based on an untrue account of equal opportunity which is devoid of historical content (p. 183). In its similarity to hokey hope and resolute hope, mythical hope “depends on luck and the law of averages to produce individual exceptions to the tyranny of injustice, and thus it denies the legitimacy of the suffering of the oppressed,” he argues (p. 184). He convincingly provides the example of President Obama’s election viewed as evidence of the end of racism. Or, as a recent study of Santa Clara County school districts across several cities showed, school gardens are most prominent in affluent schools that are relatively less diverse (Stewart, Purner, & Guzman, 2013). The mythical hope of celebrating even school gardens for all can be perpetuated until one digs deeper into the data to tease out what is beyond the surface to make visible the inequities of distribution of these gardens across socio-economic strata.

Patient Hope, Hope Deferred

In his philosophical analysis, Webb (2013) states that hope is the “human attribute which simultaneously reconciles us to our ontological status as a traveler and propels us along the path to ourselves” (p. 399). In its positive sensibility, patient hope enables the yet undefined potential of humans who are “wayfarers” to unfurl and find themselves, he explains. This notion that we are wayfarers implies that we are en route, on a journey, to that which is yet intangible. Therefore we must have faith and basic trust in ourselves that the yet undefined will be attained. Instilling a patient calm, hope allows one to relax “precisely because of the security afforded by its positive glow” and by letting life take its course, in hope, humans can feel free to let go of control; in staying neutral and resigned positively to life’s trials and tragedies, some consider such view of patient hope as also positive resignation (Webb, 2013, p. 399). In my experience in some urban schools, teachers and principals state that they understand the value of school gardens in changing eating habits while also learning content hands-on; yet, they might still defer the creation of gardens by alluding to the difficulties of maintenance or discipline control but hoping to start them on school grounds sometime in the future. Therein lies the difference between patient hope and critical hope or transformative hope. With its non-effort to change the circumstances toward an envisioned future, such hope instead is other-directed and believes in the efficacy of human agency to be content in “silence, modesty, timidity, humility, patience, relaxations, and security,” according to Webb (2013, p. 399).

The pedagogy of patient hope requires a belief in a shared journey toward a virtuous outcome. However, patient hope is also about hope deferred. Hope long deferred is hope denied, warned Martin Luther King, Jr. According to Duncan-Andrade (2009): “Hope deferred, constructed on a progressive politics of despair, is a common justification for poor teaching. It hides behind misinterpretations of research that connect the material conditions of poverty to the constraints placed on schools” (p. 185). For Duncan-Andrade, while educators might not blame the victim and while they recognize that urban youth face many challenges and feel overwhelmed by their own inabilities to maintain hope, nonetheless educators might not feel well-equipped to respond to the daunting hardships of their students by engaging a pedagogy that will develop hope. He explains that instead they turn to external factors such as the economy, lack of social services, and institution of education itself. For these teachers, there is not much beyond the public acknowledgement of social inequality, in terms of a transformative pedagogical project. They hope for change in its most deferred forms: either a collective utopia of a future reformed society or, more often, the individual student’s future ascent to the middle class, and, in so doing, they advocate that students take a path that educators themselves are unwilling to help them find, explains Duncan-Andrade (p. 185).

Sound Hope, Authentic Hope

Webb (2013) states that, as a future-oriented undertaking, sound hope is directed toward a concrete specific goal. “To hope is thus to conjure in one’s imagination a picture of the world in which the objective of one’s hope has been realised. The second—and this, for many, is precisely what renders hope something more than mere desire—is the cognitive act of believing the objective to be possible of attainment,” thus, imagining a future that is hoped for and working toward it with an attitude of possibility of success (p. 404). Sound hope can also help with countering aversion to risk. “The careful survey of the evidence characteristic of sound hope leads the hoper to identify which gambles are worth taking and which are not,” he writes (p. 405). In contrast to hokey hope, sound hope, being more realistically grounded in action, is the kind of hope that educators can embrace and nurture.

In a similar vein, David Orr (2011) offers a laudable view in Hope is an Imperative. He urges a shift in ways we think about our environmental and sustainability dilemmas from catastrophe that immobilizes action to one where “hope is a verb with its shirtsleeves rolled up.” He explains his thesis:

…when you look at the trend lines going down or up for carbon emissions or, you know, crime or whatever, if you are optimistic, you just don’t know enough. You haven’t paid enough attention. If you’re pessimistic, then you’re going to be totally ineffective. But in either case, you don’t have to do a damn thing. You just put your feet up on the top of the coffee table and neither despair nor optimism will move you, but hope may move you…If you’re hopeful, you have to do something. You can’t sit there. It’s not passive. [T]he position of hope doesn’t claim you’re going to win.” (p. xx, italics added)

Here, analogous to Webb, Orr urges us to act as hope is the wellspring of imagination and of conviviality, he explains. To understand why hope is an imperative he also encourages us to first ask, why we, as human beings, need to survive. And he further challenges us to answer: why do we deserve to survive? When we engage with such ontological questions, Orr feels our better sensibilities would emerge to respond to the rapid climate change that is impacting the planet. In the learning gardens, I find the same attitude, wherein imagination and possibility are in practice as children and youth engage with growing food alongside their peers and adults who care for them. Food provides a milieu for engagement of sound and authentic hope, of endless possibilities materializing one’s visions in practical ways. In seeing the results of their action, students feel hopeful.

Critical Hope, Transformative Hope

A hope is not a desire plus a probability estimate grounded in a survey of the evidence, but rather a utopia plus a sense of possibility grounded in a confidence in the powers of human agency. It is taking the world by the throat and insisting that there is more to this life than we have ever imagined (Rorty quoted in Webb, 2013, p. 409).

Rejecting the despair often experienced in urban schools or the false hopes of optimism that typically Americans might experience, there is yet another type of hope which Duncan-Andrade (2009) calls critical hope, a form of hope that is active and engages a commitment from individuals and communities despite and against evidence to the contrary “in order to change the deadly tides of wealth inequality, group xenophobia, and personal despair” (pp. 296–297). Paulo Freire (1997) who transformed our thinking about oppression, believed critical pedagogy to be also a pedagogy of hope. As a collective undertaking, transformative hope goes further in its optimistic undertakings by creating a vision of the kind of world we want. While this is rooted in individual experiences, it is developed as a shared and communal undertaking through discourse and dialogue. Webb concludes that transformative hope differs from critical hope by not only negating the present conditions but also by annunciating a better alternative. In having confidence in the human agency to solve problems and create better solutions as seen in critical hope, transformative hope is also a collective undertaking. For Webb (2013), the “cognitive dimension of hope in turn grounds and inspires concerted goal-directed action, i.e. the behavioural dimension of hope.” (p. 410). In this sense, then, a pedagogy of transformative hope is likely to be explicitly political, as it mobilizes action toward a better future.

Two of the most influential philosophers and critical theorists, Paulo Freire and bell hooks (2003), brought issues of inequities and oppression across rural and urban terrains to the forefront of educational discourse in order to address socio-economic injustices and issues of power and privilege. For them, “the aim of education as a political act is to move beyond dialogue, critique and the articulation of well-founded possibilities. In the face of a reality that sickens and offends, it becomes the responsibility of the educator to announce their utopian vision and to mobilise support for it, thereby transforming it into a shared utopia dream,” Webb (2013, p. 410). This places the onus of facilitation on the educator as he or she tries to lead the oppressor out of the relationship of oppression. Yet, Freire’s conscientization places human and political agency at the forefront of critical thinking and engagement mobilizing peasants and other oppressed people, as autonomous agents, to recognize and articulate oppression and themselves work toward rupturing its cycle.

Cultural critic, teacher, and activist, bell hooks (1994) also seeks practical alternatives, embracing love and engagement with the “other” in community, by not simply radicalizing education and stopping at critique as that can have a paralyzing effect for many of the underprivileged students such as the ones she taught. Transformative hope creates a sense of agency as students can articulate a better future and work toward it with support, care, and love. At thousands of schools across the country, gardens have sprouted with the support of the community, non-profits, and educators. At these sites, administrators and teachers alike are inspired by the transformative potential of school gardens in motivating those students who are often disengaged in the classroom to become actively engaged in hands-on learning in the school garden. For hooks (2003), influenced by Buddhist philosophy, love is a “combination of care, commitment, knowledge, responsibility, respect, and trust” (p. 131). Such hope is enabling and positive and also inspiring, since educators are also part of the equation in developing transformative hope. It also can foster imagination in much the same way that Martin Luther King, Jr. (1963) articulated in his speech, I have a Dream.

Regenerative Hope

Drawing from the emergent typology discussed earlier, in Figure 1, I have developed a model of a pedagogy of hope that is regenerative, with the elements shown at the pinnacles of the star in the figure: engagement and experience; care and conviviality; risk-taking and belief in possibilities; transformation and critical sensibilities; and imagination and joy (see Figure 1).

Engaging the world, not avoiding it, as hooks (2003) articulates, is an aspect of regenerative hope: the learning gardens are about hope in action, where through the practice of growing food one learns the nuances of a web of life and appreciates its intricate connectedness. A la Dewey (1938), in Teaching as Possibility, Greene (1997) argues that only when learners assume an active stance in their learning can they create a new reality. Building on Deweyan pedagogy of experience and education, the idea of understanding of the world from experience is discussed at length by Peter Kahn and Stephen Kellert (2002) who explain that “experiential contact with nature can exert a significant impact on cognitive development, especially during middle childhood and early adolescence” (p.122). In supporting practical engagement and experience, regenerative hope emerges in action that also supports human agency. This is especially needed for children and youth educated in schools that are “places where assumptions of conformity, standardization, and assimilation are woven into the fabric of everyday life” (Generette & Hicks, 2004, pp. 187-188). In such a climate, there is even more reason for schools to adopt innovative approaches that are engaging for children and youth: “In an oppressive learning climate, this means to act on behalf of the less privileged without a reasonable hope for reward and with eyes wide open to the danger of such action” (Generette & Hicks, 2004, p. 192). Van Heertum (2006) provides further insight:

Critical teachers and researchers must also embody the change they are advocating, showing students an alternative through their actions together with their words. This requires more than critique, activism and alluding to the Great Refusal; it also must include a positive dream that can inspire others to follow, embracing their creativity and beliefs. (p. 50)

Gardens teach us about care in profound ways. Mindful connections with land, soil, planting, tending, harvesting, and preserving all require love and attention. When done in community, and when embracing conviviality, the joys compensate for the hard work entailed in gardening by furthering hopeful possibilities. When there is authenticity of actual engagement in gardens at a human-scale, and when there are innumerable other such engagements across communities and locales on school grounds, then, as Paul Hawken (2007) reminds us in Blessed Unrest, real change is possible: it is the bottom-up efforts, occurring individual-to-individual, supporting change that can then bubble up to aggregate in larger social changes and possibilities. Hence, the center of the model in Figure 1 displays action and agency.

Regenerative Hope: Pedagogy of Action and Agency in the Learning Gardens

In my own life’s work I have been focused on possibilities through active engagement. This has often meant taking risks to work against the grain of modernity. First as a teacher of science (grades 6-11 and higher education) and then as a philosopher of education (higher education), I have been dedicated to ensuring that children from a young age are initiated into a way of being and learning that develops in them skills and attitudes, values and sensibilities that engage them in meaningful ways with nature. As an ethno-botanist, I am fascinated by the mysteries that unravel in the creation and growing of a garden: plants, insects, birds, animals of all sorts poised to grace a garden without a replicable formula. Gardening gives me deep insight into their potential for regenerative possibilities. In this section, I share a story of my personal engagement for almost a decade in establishing and supporting learning gardens at a school in southeast Portland, Oregon. First, I present the school context with demographics. Next, through photographs and student voices capturing their active engagement in the gardens I draw out key features of regenerative hope highlighted in Figure 1.

School Gardens: Lane Middle School as Context

Engagement with food and Learning Gardens, as important examples of embodied learning, have enabled Portland State University (PSU) students to not only think about their own health but also that of the planet, resulting in a shift in the way they learn. Guided by several urgent factors, the Learning Gardens program that I co-founded with Pramod Parajuli (2006) addresses issues related to hunger; health, such as obesity and diabetes; the growing gap between the academic performance of white and ethnic minority students; and the vulnerability of urban school children given their loss of connection with and less-than-desirable likelihood of exposure to nature. The courses that I have taught at PSU engage university students as garden educators to work side-by-side in collaboration with students in grades pre-K-8 in Portland Public Schools (PPS) District. The Learning Gardens nurture students’ love for nature, increase their understanding of growing and using edible plants, educate them about nutrition and the benefits of healthy eating habits, explore the cultural significance of foods including those from their native cultures, and demonstrate the healing properties of nature and gardening. In the Learning Gardens program, curriculum indoors and outdoors is integrated. Seasonal learning is emphasized. As children and youth learn to grow food, build gardens, and see how the health of the individuals, the health of the land, and the health of their communities are intertwined, they learn to rebuild healthy relationships with each component: learning takes on real, pragmatic, and down-to-earth meaning. A sense of agency develops.

Among partnerships at a dozen Learning Gardens at District sites, including Title 1 high poverty schools, PSU has also partnered with Lane Middle School in the initiation and design of the Learning Gardens Laboratory (LGLab). LGLab is built opposite the school on a 13-acre property that includes several greenhouses. Since 2005, Lane adolescents and their teachers have participated directly in the gardens, connecting the academic content in science in particular, and also other subjects, with hands-on garden-based learning. In partnership with the teachers, PSU garden educators offer an integrated seasonally-based curriculum coordinated with the in-class topics. In recent years, emphasis is placed on science as a subject matter that incorporates Oregon Benchmarks and Next Generation Science Standards (Williams et al., in press). Focusing on principles of ecological systems, permaculture, multi-cultural contexts, and active learning, the curriculum is grounded in both a sense of place and stewardship for the land. Participation in LGLab not only engages low-income and culturally diverse youth in the challenging academic activities but also provides hope given their often uprooted home lives.

One of the most culturally and linguistically diverse schools in the PPS District, Lane Middle School has about 450 students ages 11 to 14 years old in grades 6 to 8: 62% of its students are minorities/non-whites; 43% speak English as a second language; 22 languages are spoken at home. Socioeconomically, students come from predominantly low income families: 80% of students qualify for free or reduced-priced lunch. The area has historically lacked economic vitality, and the lives of students often include family instability due to underemployment, new immigrant and/or refugee status, violence, drugs, and incarceration. Historically, the school has had low academic achievement (Williams, 2012).

Each week, about 30 sixth grade students per class come to the Learning Gardens with their science teacher for a 90-minute block. There are six sixth grade sections. The embodied learning experiences are particularly poignant as many of the students and their families are new immigrants and/or refugees from countries across the globe. For the students, engagement with soil in the learning gardens is a means to feel rooted in place and connect to community. They long for a place they can call home. In the learning gardens. their history of uprooted lives changes direction as they develop a sense of place (Williams & Anderson, 2015) and create memories.

In 2014, 39 sixth graders were interviewed about their experiences of learning in the gardens at their school. Data were obtained through 11 focus groups of two to five students, lasting 35 minutes to 60 minutes each. The focus groups were audio-taped. These were transcribed verbatim and analyzed using the NVivo program. Among the open-ended questions, students were asked: What are you learning in the gardens? What skills have you learned? What is your favorite part about being in the garden? What do you like the least about being in the gardens? For the vast majority of students, gardens were a positive alternative to classroom learning; their concerns were about being out in the rain and cold or getting their clothes and shoes muddy. None of the students were critical of the educational aspect of learning in the garden. I have used the five sets of elements seen at the pinnacles of the model of regenerative hope in Figure 1, to present student voices that confirm experience and engagement, care and conviviality, risk-taking and belief in possibilities, transformation and critical sensibilities, and imagination and joy. I have intentionally chosen to let the student voices emerge in order to provide in-depth flavor of students’ own sensibilities that emerge in the learning gardens. The collective analysis of their views is presented at the end of the section.

Experience and Engagement

We learned how to replenish the dirt…we took rakes and hoes and there was this plot that was filled with weeds and we were trying to do cover crops for the Winter so we had to get out the weeds and stuff and we saw like a lot of worms and we learned what cover crops do. They help keep the nutrients in. So the dirt can stay good for other plants and stuff. It basically makes sure that the dirt keeps doing its job and then it just doesn’t become dead soil …

Here [in the Learning Garden], it is like school but it isn’t ’cause you are learning something but you are learning it in a fun way. So it’s almost not like school but it is still. It’s cool. It’s engaging. We get hands-on experience while learning so we actually know what we are actually learning.

We use all of our senses. Touch, smell, hear, see, taste. There’s so many healthy things growing here. When we’ve grown and it is new and fresh, it tastes a lot better than some of the store bought things and here it is right out of the garden. All you have to do is rinse it off.

I get to work the soil and plant. It’s hands-on instead of talking about it, I get to dig and get messy. That’s my favorite thing… We are learning about decomposing, planting, and just what nature does for us. Those [earthworms] help the soil because they eat the waste and then they make soil.

Care and Conviviality

What I feel about the gardens is that I’m taking care of something with everyone else. You learn to work together. How to plant, how to pick the plants correctly and if you don’t pick it correctly, the plant would die.

I like that we can garden and make the world a better place. We get to plant food, and learn how to plant it, how to help the earth in other ways and I like when we go outside and plant and stuff like that…

I feel really happy when I am taking care of plants…makes me feel like I’m doing good not only for the plants but for me also.

It kind of also teaches you about working in groups and how to work together…you have to do …all sorts of stuff in groups… I feel that the learning gardens [is] a great experience and time to bond with each other.

Transformation and Critical Sensibilities

It teaches you responsibility and knowledge about plants and animals and bugs but also you get to know yourself since everything is connected.

I learned how to plant. How not to fertilize artificially, because it’s not healthy to eat stuff that’s been fertilized …with chemicals, it’s healthier to eat organic. We learn what season it is and what to plant in what season… I learned not to plant certain things in winter because it’ll die.

Learning gardens has really inspired me to help me eat healthier. Although, even before I was trying to eat healthier too, but it’s inspiring me a lot more. And it’s inspiring me to bake healthier things and cook and stuff…

We learned that everything has patterns…the leaves with their veins, the trees and their rings; the wings on the insects.

Risk-Taking and Possibilities

Learning gardens are teaching me that we are capable of anything when we put our minds to it.

I feel that the learning garden has helped me feel more comfortable with expressing myself and being able to be who I want to be.

We have been learning on how to not waste useful things and to harvest energy in different ways and we have learned how to plant and grow our own food and…not throw away stuff.

I like how it smells and we get out instead of sitting in our seats all day. I get to be in nature. I get to do things not many other schools get to do.

Joy and Imagination

I like that in the garden we get to do things by ourselves… I like that we get to go outside and enjoy nature, I like the sun and relaxing. Just sitting down and enjoying life. That is a really good thing about the garden, if you don’t feel so good the garden’s fresh air can really help. I also like the plants and getting to see pretty trees and plants. I like when the groups come together….because we aren’t always with our friends when in our assigned groups in the classroom.

Here I get a chance to be with nature…I also get a chance to expand my knowledge about gardening, nature, etc. I can be with my friends at the same time. I like being outside and being able to learn about plants and nature.

It’s not every day you get to be with all this green beauty….The air out here is fresher, almost like in the country. And it is very enjoyable.

We are learning how to compost waste. How to use dead plants making it turn into real beauty making our own soil. I like being outside. [In school] you don’t have the outside smell of the Learning Gardens and fresh air.

As seen in the student voices and photographs above, learning gardens provided them with opportunities to learn through active hands-on experiences about various relationships, connections, and skills for gardening. They learned about composting and soil making, the role of worms, patterns in leaves and insect wings, nuances of collaborating, caring and being attentive, finding beauty in simple things, and the fact that they could breathe, be outside, and learn in fresh air. This is empowering for students who come from communities and homes in poverty where many live in Section 8 housing.

Action and Sense of Agency

Garden learning is about risk-taking; it is about going beyond the norms and comforts of the traditional classroom to engage students. I share below, how a sense of agency also emerged in student expressions especially as they were able to clearly articulate the difference between the classroom environment and what happened in the garden. They referred to the Learning Gardens in tangible terms of actually doing things hands-on in an environment that was vastly different than a classroom. A sense of agency emerged as they shared that their experiences of learning in the garden changed how they were learning. These expressions of transformative learning (Wood & Hicks, 2001; Generett & Hicks, 2004) are poignant:

If you were in a classroom and you were learning, you would be kind of bored…I think learning gardens is really worth it…because you are not learning like you are inside…You could have something in front of your desk that is like learning gardens but it is not like getting out and doing it yourself outside. You are not getting fresh air while doing it. It is pretty relaxing too. Depending on what you are doing, it can be fun…you don’t really realize that you are learning but you actually are learning.

It’s different here in the garden than learning this in the classroom. In the classroom you are just studying it and looking at pictures or reading about it but here you can actually look at plants and learn to grow things.

…doing hands on stuff to learn is better because in the classroom people get stuck but when they are out here learning, it is more fun and exciting because then you do hands on stuff, it literally gets stuck in your brain but when you do it in the classroom it doesn’t. It just goes in one ear and out the other.

Here we plant and do more stuff outside. In school we just sit in a chair and just learn. Here we get a lot of exercise, fresh air. We walk around. It’s fun. My brain’s working harder. I’m moving around. In class I fall asleep. At learning gardens, we learn a lot at the same time.

The sixth graders were able to articulate that learning in the garden was different from their in-class experience; they could discriminate among the experiences. While it was fun, they were able to also recognize that when actively engaged in growing things, what they learned was “stuck” in the brain. They could remember better. Movement, breathing fresh air, and doing by learning were all essential factors as was working in groups. Their comments confirm my observations of students being focused on the task almost contemplatively, yet, being with their peers working in garden plots gives them opportunities to interact with one another. Much of research shows that touch, taste, sight, smell, and hearing, assist us with engagement in learning, developing in us sensual awareness, often unspoken (Williams & Brown, 2012; Sewell, 1995).

Significance

As concern for social justice continues given the achievement gap between African-American, Native-American, and Hispanic students relative to their White and Asian peers, the growing school garden movement provides an opportunity to engage students in authentic, real-world holistic garden-based learning. Such engagement in and with the learning gardens generates a type of hope which I have called regenerative hope: hope that creates practical possibilities, hope that fosters imagination as life-less grey concrete is converted to humus-enriched soil that supports the miracles of life, and hope that rouses the hitherto desensitized senses into remembering our connection to soil and food, and in the process of doing so, to our bodies. Growing food also brings joy and feeds curiosity and wonder that are innate in all children and youth.

In the school gardens, students learn about relationships with one another and with the plant and animal worlds. For many, whose lives have previously been filled with despair given their intergenerational poverty and dislocation from home cultures and historical roots, learning finally develops meaning. Engagement in the gardens can bring a sense of hope: hope that is regenerative and revitalizing in much the same ways that the bees pollinate the flowers in beds the students have planted, or the mint tea soothes our guts, or the blazing sunflower invites birds to pick the seeds, or sister corn glows in the morning sun reminding how intricately she is connected with sister bean and sister squash. The numerous friendships and convivial human and more-than-human relationships that are evident in the gardens convey revitalization. It is in the learning gardens that I find that youth thrive through active engagement as they develop new sensibilities about learning academics and also their own connections with food and soil.

For regenerative hope, a shift must occur from individual dreaming and critique to collective community and convivial relationships in the process of knowledge construction. The learning gardens deliberately nurture affective attachments and passions that surface during the hands-on learning. This is where Gandhian education championing the three Hs – heart, hand, and head – all are used in order to bring dreams and hopes into fruition (Gandhi, 1953). Wendell Berry (2010) provides profound wisdom in that hope is grounded in the here and now — in soil, land, and community — in this particular place where we live:

…Found your hope, then, on the ground under your feet.

Your hope of Heaven, let it rest on the ground

underfoot. Be it lighted by the light that falls

freely upon it after the darkness of the nights

and the darkness of our ignorance and madness.

Let it be lighted also by the light that is within you,

which is the light of imagination… (pp. 92-93)

Standing on the first page of Adrienne Rich’s “end of despair” also means that we need Berry’s sensibilities for hope to sprout from the ground under our feet. For the youth living in depressed neighborhoods and for whom society has generally given up hope, the care, engagement, convivial relationships, and a sense of possibilities that are reflected in the learning gardens are worth the effort. Defying determinism for a hopeless future, the youth develop a sense of agency in a myriad of ways through active engagement as the learning gardens offer regenerative possibilities.

Notes

Photos are courtesy of Jennifer Anderson, Marcia Thomas, and Dilafruz Williams. I am grateful to the Portland State University garden educators and the teachers and students at Lane Middle School for their sincere engagement with the Learning Gardens Laboratory.

References

Berry, W. (2010). Leavings: Poems. Berkeley, CA: Counter Point Press.

Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and education. New York: Macmillan. Duncan-Andrade,

Freire, P. (1997). Pedagogy of hope. New York: Continuum Books.

Gandhi, M. K. (1953). Towards new education. Navjivan: Ahmedabad, India.

Generett, G. G. & Hicks, M. A. (2004). Beyond reflective competency: Teaching for audacious hope-in-action. Journal of Transformative Education, 2(3):187-203.

Greene, M. (1997). Teaching as possibility: A light in dark times. The Journal of Pedagogy, Pluralism & Practice, 1:1-11.

Hawken, P. (2007). Blessed unrest: How the largest movement in the world came into being and why no one saw it coming. New York: Penguin.

hooks, b. (1994). Teaching to transgress: Education as the practice of freedom. New York: Routledge.

hooks, b. (2003). Teaching community: A pedagogy of hope. New York: Routledge.

Kahn P. & Kellert, S. (2002). (Editors). Children and nature: psychological, sociocultural, and evolutionary investigations. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

King, M.L.K., Jr. (1963, August 28). “I have a dream.” March on Washington. Washington, D.C. Retrieved November 18, 2015, from http://www.mlkonline.net/dream.html

Orr, D. (2011). Hope is an imperative. Washington: Island Press.

Parajuli, P. (2006). Learning suitable to life and livability: Innovations through Learning Gardens. Connections: The Journal of the Coalition for Livable Future, 8(1): 6-7.

Pettit, P. (2004). Hope and its place in mind. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 592:152–165.

Rich, A. (1993). Dreams before waking. In Your native land, your life (p. 46). New York: Norton Press.

Sewell, L. (1995). The skill of ecological perception. In M. Gomes, A. Kanner, & T. Roszak. (Eds.), Ecopsychology: Restoring the earth and healing the mind, (pp. 201-215). Berkeley: The University of California Press.

Stewart, I. T., Purner, E. K. & Guzmán, P. D. (2013). Socioeconomic disparities in the provision of school gardens in Santa Clara County, California Children, Youth and Environments 23(2): 127-153.

Van Heertum, R. (2006). Marcuse, Bloch, and Freire: Reinvigorating a pedagogy of hope. Policy Futures in Education, 4(1): 45-51.

Webb, D. (2013). Pedagogies of hope. Studies in Philosophy of Education 32:397–414.

West, C. (2004). The impossible will take a little while. In P. Rogat (Ed.), The impossible will take a little while: A citizen’s guide to hope in a time of fear (pp. 293–297). New York: Basic Books.

West, C. (2008). Hope on a tightrope. New York: Smiley Books.

Williams, D. R. (2012). Multiculturalism and sustainability education: Engagement with urban school communities via food and Learning Gardens. In McDonald, T. (Ed.), Social responsibility and sustainability: Multidisciplinary perspectives through service learning. Pp.146-161. Sterling, VA: Stylus.

Williams, D. R. & Brown, J. D. (2012). Learning gardens and sustainability education: Bringing life to schools and schools to life. New York: Routledge.

Williams, D. R. & Anderson, J. A. (2015). Tongue-tied no more: Diversity pedagogy and sense of place in the Learning Gardens. Canadian Journal of Environmental Education 20:26-46.

Williams, D. R., Kelley, S.S.; & Sneider, S. I. (in press). Science in the Learning Gardens: Designing middle school curriculum integrated with Next Generation Science Standards. In Barnett, M. et al. (Editors). STEM learning through urban agriculture and garden. New York: Springer.

Wood, D. R. & Hicks, M. A. (2001). Loosening the bonds of conventionalism: Problems and possibilities of a transformative pedagogy. Teacher Development, 6(1): 89-103.

Dr. Dilafruz R. Williams is professor and co-founder of the Leadership for Sustainability Education (LSE) program at Portland State University, Portland, Oregon. She is co-author of Learning Gardens and Sustainability Education: Bringing Life to Schools and Schools to Life (Routledge) and co-editor of Ecological Education in Action: On Weaving Education, Culture, and the Environment (SUNY). She is recipient of several awards and grants. An avid gardener, she is also co-founder of the Learning Gardens Laboratory and the Sunnyside K-8 Environmental School in the Portland Public School District. These successful initiatives address ecological and cultural foundations of K-12 and higher education with strong community-university-school partnerships. She was elected city-wide and served on the Portland Public School Board 2003-2011. She is Principal Investigator for “Science in the Learning Gardens: Factors that Support Ethnic and Racial Minorities in Low-Income Middle Schools” funded ...

Dr. Dilafruz R. Williams is professor and co-founder of the Leadership for Sustainability Education (LSE) program at Portland State University, Portland, Oregon. She is co-author of Learning Gardens and Sustainability Education: Bringing Life to Schools and Schools to Life (Routledge) and co-editor of Ecological Education in Action: On Weaving Education, Culture, and the Environment (SUNY). She is recipient of several awards and grants. An avid gardener, she is also co-founder of the Learning Gardens Laboratory and the Sunnyside K-8 Environmental School in the Portland Public School District. These successful initiatives address ecological and cultural foundations of K-12 and higher education with strong community-university-school partnerships. She was elected city-wide and served on the Portland Public School Board 2003-2011. She is Principal Investigator for “Science in the Learning Gardens: Factors that Support Ethnic and Racial Minorities in Low-Income Middle Schools” funded ...