Privilege as Practice: A Framework for Engaging with Sustainability, Diversity, Privilege, and Power

Full PDF: Kolan & Sullivan JSE Vol 7 Dec2014

Full PDF: Kolan & Sullivan JSE Vol 7 Dec2014

Abstract: This paper explores the intrinsic but often weakly developed links between sustainability and issues of diversity, power, and privilege. It offers a systems-oriented conceptual framework for exploring and understanding how issues of diversity, power and privilege operate in social-ecological systems. This framework can be used as a learning tool with a wide array of audiences (higher education, organizational development, adult learners) and educational contexts (including but not limited to sustainability education programming).

Keywords: Sustainability, privilege, power, diversity, multicultural, education

Introduction

The premise and promise of sustainability is rooted in the belief that no effort to restore ecological balance and integrity will succeed if it does not also address the social inequities and human suffering in our communities. Similarly, no effort to end social inequities and combat human suffering will be successful without clean air, water, and healthy and balanced ecosystems. Yet despite the growing call to address environmental and social challenges in an integrative way, many sustainability practitioners and professionals still focus their efforts on traditional disciplinary environmental issues; ignoring the systemic implications of privilege and power in their analysis and strategy development (Littig & Griessler, 2005; Pearsalla & Pierce, 2010; Portney, 2003). This pattern is mirrored in many sustainability education programs and courses that fail to include power and privilege analysis or cultural competency skills as a part of their curriculum.

The historical circumstances and injustices that have led to this larger pattern within the environmental and sustainability movements are important to understand and have been described in great detail by a number of scholars and authors (Agyeman, Bullard, & Evans, 2002, 2003; Enderle 2005; Gelobter et al. 2004; Taylor, 2000). While it is becoming more common for sustainability initiatives and educational programs to make mention of these issues, efforts to address them in a systematic or rigorous way are unusual (Bonta & Jordan, 2005; Collin & Collin, 2001; Forbes, 2011). Ultimately, many who identify with the term sustainable (or other related fields such as regenerative, resilient, adaptive, etc.) have simply adopted new language to codify many of the same strategies that grew out of the environmental movement (Agyeman, 2005).

The field of sustainability has generated a variety of conceptual frameworks and tools (Burns, 2012; Fiksel, 2006; Zhang, Baral, & Bakshi, 2010) that can be utilized by educators and practitioners to better understand the complexity of natural resource and environmental issues (Ecological Footprint, Life Cycle Assessment, etc.). However, there have been fewer conceptual frameworks that have come from within the sustainability field that help us better understand the ways that power and privilege influence social-ecological systems (Edwards, 2005).

This paper offers a systems-oriented framework for analyzing, understanding, and engaging with issues of privilege and power in social-ecological systems. The sections below provide context, framework goals, a description of the framework, practical implications, practices for effectively utilizing the framework, and a glossary (terms that are bolded and italicized below are more specifically defined in Table 1 below).

The authors have used this framework extensively over the past 6 years with a range of audiences and community groups in a variety of educational contexts (e.g., graduate and undergraduate course, faculty development, professional leadership programs, organizational development efforts). Many of the central elements of this framework build on the insights of Kaylynn Sullivan TwoTrees from her experiences addressing issues of difference, power, and privilege, especially following repeated encounters with Peggy McIntosh’s (1989) framework on White privilege. As a woman of Color, Kaylynn was interested in expanding the context for conversations on privilege and deepening the complexity of analysis (from a “have vs. have not” mindset to a broader understanding of “degrees of privilege”). Linda O’Toole’s (2008) work on dimensions of difference was influential in further development of this framework. Marie Vea-Fagnant and Nancy Gabriel also provided important contributions to this framework.

Framework Context: The Ecological Roots of Diversity

According to Merriam-Webster (2013), diversity is “the state or quality of being different or unique.” This principle is one of the most striking and defining patterns of healthy ecosystems. As physicist Fritjof Capra (2004, p. 8) notes: “When you look at an ecosystem – say at a meadow or a forest – and you try to understand what it is, the first thing you recognize is that there are many species there. There are many plants, many animals, many microorganisms.”

Further inquiry into the principle of diversity reveals a variety of important functions and patterns. Diversity can be observed at many levels of organization within living systems (from genes, to species, to populations, to communities, to ecosystems). From an evolutionary biology perspective, diversity is the raw material for systems to adapt or evolve in response to changing conditions. And while the specific relationship between diversity and resilience is complex and nonlinear, greater diversity often correlates to a more healthy, resilient, and flexible ecosystem. As Nellie McLaughlin (2004, p. 28) describes, “Differentiation is the process through which the universe sustains life.”

Through the process of differentiation we arrive at another basic fact of life: that everyone is unique. This simple and somewhat obvious statement has significant implications when we consider the challenges associated with working together, creating community, and collaborative decision-making.

Research on group dynamics has shown that greater degrees of difference in social settings correlate with increased resilience (Lozano, 2007) and even creativity (Simonton, 1999). Scott Page (2007) has further shown that groups that display a diverse range of perspectives and heuristics usually outperform groups of like-minded experts at solving challenging problems by a substantial margin.

Why is this only “usually” the case? The same forms of difference that enhance resiliency, creativity, and ability to solve problems can also lead to significant social challenges and conflict. This is the paradox of diversity. Throughout history, diversity has provided the raw material for evolution of language, philosophy, and social and material innovation. And at the same time, humans have often used difference (e.g., skin color, spiritual belief systems, sex, learning styles, political affiliation, sexual orientation, etc.) as a basis for oppression and violence. Human history and the present day offer countless examples of persecution on the basis of differences.

This history and legacy of oppression has led to a pattern where many forms of difference are culturally isolated and oppressed. In the absence of authentic and reciprocal relationships across difference, we miss out on the potential creativity, adaptability, and resilience that diversity can bring.

Framework Goals

We are interested in enhancing our collective ability to engage with difference to strengthen relationships and improve the health of the systems that we inhabit. The following framework outlines an analytical system and a form of practice that we are calling Privilege as Practice. The specific goals of this framework include:

- Deepening and expanding our capacity for self-awareness

- Furthering our ability to understand our own particular uniqueness to better understand how we each flourish and thrive

- Learning to recognize how systemic structures, norms, and processes preference certain differences over others

- Learning to identify degrees of privilege and recognize how multiple identities interact (intersectionality) in different social systems

- Building capacity to use our privilege and power to benefit the health and well-being of the systems that we inhabit

- Tending to the impacts of historical and present day forms of oppression and trauma

The Systemic Progression

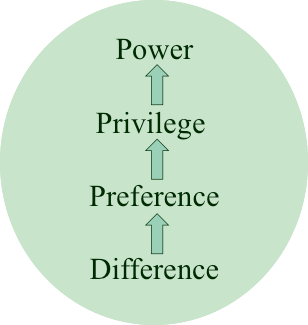

As described above, diversity is a simple fact of life. Difference exists in all systems and has the capacity to be the raw material for adaptation, creativity, and resilience. Yet in many social systems, we find that accrued power is used to oppress, homogenize, and assimilate expressions of difference that do not fit with the dominant perspective or ideology. This pattern causes harm, limits the potential of individuals in the system, and consequently diminishes the wisdom and creativity of the group. We believe that understanding the primary dynamics and processes associated with this pattern can be helpful in building our capacity to engage with difference with well-being in mind. Figure 3 below illustrates the common pattern and progression by which certain differences accrue power in social systems.

Figure 3. The green circle in this diagram represents any social system (an organization, community, school, family, etc.). The progression shown in the circle begins with difference and illustrates a common pattern by which power is accrued by individuals who embody certain characteristics.

This progression can be used to track a variety of differences (internal, external, socially constructed, etc.) as they play out in a variety of different social systems across different scales. Like any conceptual framework, the patterns illuminated by this progression can be helpful in understanding power and privilege dynamics, and it is important to remember that this representation is a simplified interpretation of complex system dynamics.

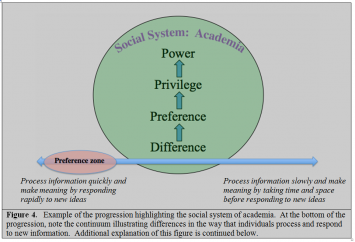

To illustrate how the progression can be used, we offer an example (shown below in Figure 4) that highlights the system of academia and one type of difference: how we process and respond to new information.

Individuals vary greatly in their optimal approaches to processing and responding to new information. Some individuals process information quickly and make meaning by responding promptly, with very little silence or space between comments. For these individuals, fast-paced conversations are often invigorating and stimulate new insights and ideas. Others prefer a slower-paced conversation that offers time and space for reflection and consideration before a response is offered. For these individuals, slower-paced conversations that involve significant opportunities for personal reflection, might be ideal. While processing and responding styles can be very complex and diverse, for the purpose of this example, we ask you to consider these two approaches at the end of a continuum. Within this continuum, individuals likely have an optimal zone where they function best.

It is important to note that differences just exist; they are value-free. One approach to processing/responding is not inherently better or worse than another. However, as we move up the progression we find that one zone of the continuum is often preferenced over others in a given system. For example, many academic systems preference fast processing and responding (the red zone indicated in Figure 4). As a result, social value is given to those who process and respond quickly in that system and social structures, rules, and norms reinforce this preference. For example, professors often ask questions in class that demand a quick response. Tests are often conducted in short timeframes. In faculty meetings, there is rarely space to offer an opinion if you can not respond quickly.

When social value is given to one difference at the expense of another, a mainstream/margin dynamic is created. In this example, individuals who embody the preferred dimension of difference (quick processing/responding) become part of the mainstream group, while those who take time and space to reflect and respond more slowly become part of the marginalized group.

These social norms, conditions, and structures combine to create a system that offers unearned privilege to those individuals who process and respond quickly to new information. In other words, those with fast processing/responding styles are often given advantages, opportunities, and choices that are not available to those with slower, reflective processing styles. These advantages, opportunities, and choices might include relationships with faculty, better grades, promotion, inclusion on committees, public invitations to speak, or awards. Often these privileges and the underlying norms are not explicitly stated (you won’t find them in organizational operations manual) and may seem invisible to those who benefit from them. Yet they tend to be plainly obvious to those who are impacted and marginalized by them.

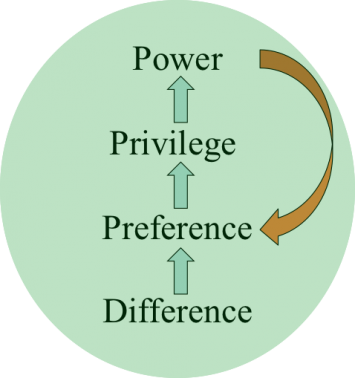

Over time, this accumulated unearned privilege provides more opportunity for quick processing/responding individuals to acquire power to exert influence or control in a system. This power is often used (sometimes unconsciously) to strengthen or reinforce organizational norms, structures, and processes that continue to benefit fast-processers and responders. For example, faculty meetings might be facilitated without space and time for reflection, or student grades might be based on class participation that is assessed by in-class responses to questions. As a result, fast processing and responding is further reinforced and preferenced (see feedback loop in Figure 5).

Figure 5. In this progression, power is used to reinforce the status quo and the preferences, norms, and structures that confer privilege and power (as represented by the orange feedback loop). In this type of system, differences are minimized and oppressed. We call this archetype success to the successful.

When power is used to further reinforce mainstream norms, those students, staff, and faculty members who prefer to process and communicate more slowly might 1) assimilate and adapt to a mode that is not optimal for the expression of their unique gifts, or 2) leave academia and find another system where they can participate more fully. As a result of either of these options, the health of the group can suffer.

It is important to note that different systems can have varying preference zones (and associated patterns of power and privilege). For example, certain contemplative communities may preference slower processing and reflection; creating a system of advantages and opportunities for those who take more time and space before responding to new ideas. Furthermore, there are many types of differences that are present and intersect within a given system. While an individual might gain privilege for their processing speed, they might also be marginalized as a result of other differences (e.g., race, class, gender, age, sexual orientation). These complex dynamics that are influenced by multiple forms of difference are often referred to as intersectionality (Choo & Ferree, 2010; Collins, 1998; Crenshaw,1991).

Practices for Engaging Difference, Privilege, and Power

Understanding the pattern of “success to the successful” is critical to our ability to intervene and create something different. While there are many cases of intentional oppression and minimization of difference, there are also many situations where individuals in the mainstream group are unaware of their own privilege and are unconsciously supporting and reinforcing the status quo.

Part of the practice of engaging difference differently, involves honing our tracking and observational skills; learning to recognize the patterns associated with systems that minimize and oppress differences. In addition to improving our awareness and analysis skills, it is also critical that we develop skills, capacity, and courage to interrupt the dominant system archetype; using the privilege and power we have to find places in systems where we can leverage change to make the system healthier. This might involve changing our own behaviors, illuminating and influencing system dynamics, or tending to the impacts of marginalization and oppression.

In many conversations about diversity, the terms power and privilege have taken on a negative connotation. And while power is often used to reinforce the status quo, minimize and oppress difference, and create norms/structures that confer unearned privilege and power to a select few, it can also be used to interrupt those cycles and create healthier systems.

As an example, we were recently told the story of a White woman who entered a popular women’s clothing store. After wandering around the store, she realized that all of the models in the big glossy photos on the walls were White. After some deliberation, she approached the store manager and pointed out this pattern and suggested that the photos be changed to include women of Color. She said that she wouldn’t shop at a store that wasn’t making an effort to break the often unconscious patterns of White privilege. The store manager responded defensively, offering all of the reasons that the photos on the wall were out of her control. The customer pressed on, asking to file a formal complaint with the corporate headquarters. Upon leaving the store, the customer was stopped by an employee of Color who told the customer that she had been waiting years for a White person to finally point out that pattern and use her White privilege and power to make a change. She explained that as a woman of Color, any critique that she might offer about the racial identities depicted in the photos could too easily be explained away by “oversensitivity” or a “chip-on-the-shoulder.”

This story of solidarity illustrates a different practice for engaging difference, privilege and power. Rather than using the unearned privilege and power associated with her whiteness to reinforce the status quo (or simply ignore the issue completely), the customer in this example used her power to attempt to interrupt the cycle of oppression.

This practice can also be seen in the actions of countless individuals from marginalized identity groups who use their power or privilege (sometimes from a different identity) to leverage change or shift mindsets. In a recent group retreat setting that we facilitated, one Indigenous participant named a divisive dynamic that was emerging in the group. His actions created the possibility for participants to notice this pattern and respond to each other differently. In this case, the participant relied on the power that he had earned through his personal integrity and deep capacity for relationship demonstrated throughout the week. His perspective illuminated the underlying mindset and behavior of the group without typing or blaming any one individual for the pattern.

There are countless other examples of individuals who use privilege and power to forge alliances and collaborations to change the ideology of oppression or transform the norms and structures that would otherwise preference certain differences. Committing to this work and exploring how we each might engage differences to participate in fostering well-being of self, community, and the larger system is essential to the practice.

| Table 1. Glossary of Terms |

| Difference is a quality or way in which things are not the same.

Preference is the assignment of social value to certain differences at the expense of others.

Privilege is a system of advantages, opportunities, and choices not available to all.

Power is the capacity to exert influence or control in a system.

Dimensions of difference are the innumerable ways that we are uniquely ourselves.

A person’s unique potential is the aggregate of one’s dimensions of difference (named and unnamed).

Mainstream/margin dynamics are present in a system when an expression of difference is preferenced. An individual is part of the mainstream when they embody a quality or characteristic that is dominant in a system and when they can benefit from the privilege associated with that group. An individual is part of the marginalized subgroup when they embody a quality or characteristic that is diminished, minimized, or oppressed.

Intersectionality refers to the complex ways that dimensions of difference interact and intersect within a given system. |

Privilege as Practice Key Elements

We believe there are a wide range of approaches to building capacity to engage with difference in ways that promote the health and well-being and individuals and systems. Rather than outline a particular curriculum or set of experiences, we’ve found it more useful engage a series of core routines and practices.

- Working from the inside out

Often conversations about diversity, power, and privilege begin with socially constructed and emotionally charged forms of difference (race, gender, class, etc.). While addressing these differences and their associated patterns of oppression are of critical importance, this framework approaches diversity from the inside out – beginning by exploring and engaging with more subtle, and less charged forms of difference from each person’s own direct experience (such as distinct ways of learning, knowing, processing, and expressing ourselves). The purpose of this starting point is to establish an environment where everyone can participate in the conversation while shifting the entry point for the conversation about difference.

We often begin our collective work on diversity and privilege by inviting group members to engage in self-reflection about individual internal differences (such as our sense of time, or our patterns for processing new information). These topics tend to be lower risk and often shift the traditional position from which we might engage in the conversation. By beginning in this place, participants can begin to recognize systemic archetypes of power and privilege and build capacity to engage with the tensions around difference for the more emotionally and socially charged conversations around race, culture, class, and gender. It also results in the discovery that there is often more diversity than originally acknowledged (especially in groups that have less racial diversity).

Furthermore, this process builds self-awareness of what we each need in a system to thrive, and conversely how the socialization process can oppress our own essential nature.

- Engaging with tension

It is important to note that the presence of difference within a system will create tension. When differences are expressed in a group setting, many facilitators, teachers, leaders (or others with power) immediately attempt to diffuse the tension by avoiding, ignoring, or silencing the non-dominant voice or different perspective. This only has to happen once in a group setting before individuals internalize that difference is not welcome.

When difference and tension are not welcome in a system, the possibility for authentic relationship is lost, as is the chance for people to learn from multiple perspectives. However, if tension is held in a healthy way (and there is a strong network of trusted relationships), it can serve as generative force – allowing us to reach a deeper understanding and tap into a larger pool of creativity.

- Emphasizing reciprocal relationship

The study of ecology reminds us that even though everything may be different and unique, it is inextricably connected. Nothing can exist in isolation. As Capra and Pauli (1995, p. 4) suggest:

All members of an ecosystem are interconnected in a vast and intricate network of relationships, the web of life. They derive their essential properties and, in fact, their very existence from their relationships to other things. Interdependence – the mutual dependence of all life processes on one another – is the nature of all ecological relationships. The behavior of every living member of the ecosystem depends on the behavior of many others. The success of the whole community depends on the success of its individual members, while the success of each member depends upon the success of the community as a whole. Understanding ecological interdependence means understanding relationships…Nourishing the community means nourishing those relationships.

Unfortunately in many social systems, the quality of relationships takes a back seat to solving problems and action. Yet when relationships are nurtured within systems, people often feel safe enough to take risks, make mistakes, and explore new territory. Strong reciprocal relationships create conditions for people to accept and offer feedback and be open to multiple perspectives in a way that is more challenging when we are learning in isolation. Bryk and Schneider (2002) refer to this dynamic as relational trust; the sense of mutual respect and trust among members of a learning community.

Conclusion

We believe that this Privilege as Practice framework can be complementary to many other important frameworks that address issues of diversity, power, and privilege (such as social justice, intercultural competency, etc.). As an analytical and largely intellectual framework, we have found it is most effective when used alongside intercultural skills and learning experiences that activate the heart and animate the spirit. We hope that the concepts described above might enhance and expand our practice of engaging with difference in service to healthy living systems while contributing to our ability to practice a more integrative and inclusive approach to sustainability efforts and education.

References

Agyeman, J. (2005). Sustainable communities and the challenge of environmental justice. New York: University Press.

Agyeman, J., Bullard, R., & Evans, B. (2002). Exploring the nexus: Bringing together sustainability, environmental justice and equity. Space and Policy, 6 (1), 77–90.

Agyeman, J., Bullard, R., & Evans, B., (2003). Just sustainabilities: Development in an unequal world. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Bonta, M. & Jordan, C. (2005). Diversifying the American environmental movement. In E. Enderle, (Ed.), Diversity and the future of the environmental movement. New Haven, CT: Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies Press.

Bryk, A. S., & Schneider, B. (2002). Trust in schools: A core resource for improvement. New York: Russell Sage Foundation Publications.

Burns, T. R. (2012). The sustainability revolution: A societal paradigm shift. Sustainability, 4(6), 1118-1134.

Capra, F. (2004). Ecology and community [Essay]. Retrieved December 2, 2012, from http://ecoliteracy.org/essays/ecology-and-community

Capra, F., & Pauli, G. (1995). Steering business toward sustainability. Tokyo: United Nations University Press.

Choo, Hae Yeon & Myra Marx Ferree. (2010). “Practicing Intersectionality in Sociological Research: A Critical Analysis of Inclusions, Interactions, and Institutions in the Study of Ineqialities.” Theory and Society. 28(2): 129-149.

Collin, R.W. & Collin, R.M. (2001). Sustainability and environmental justice: Is the future clean and Black? Environmental Law Reporter, 31, 10968-10985.

Collins, P. H. (1998). It’s all in the family: Intersections of gender, race, and nation. Hypatia, 13(3), 62-82.

Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review, 1241-1299.

Diversity. (n.d.). In Merriam-Webster online. Retrieved from http://www.merriam-‐webster.com/dictionary/citation.

Edwards, A.R. (2005). The Sustainability Revolution: Portrait of a Paradigm Shift. New Society Publishers: Gabriola Island, Canada.

Enderle, E. (2007). Diversity and the future of the U.S. environmental movement. New Haven, CT: Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies Press.

Gelobter et al. (2004). The soul of environmentalism: Rediscovering transformational politics in the 21st century. Oakland, CA: Redefining Progress.

Fiksel, J. (2006). Sustainability and resilience: Toward a systems approach. Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy, 2(2), 14-21.

Forbes, P. (2011). Transforming conservation for the 21st century. Conservation Biology, 25(2), 209–211.

Littig, B., & Griessler, E. (2005). Social sustainability: a catchword between political pragmatism and social theory. International Journal of Sustainable Development, 8(1), 65-79.

Lozano, S. (2007). A model to test how diversity affects resilience in regional innovation networks. Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Stimulation, 10(4).

McIntosh, P. (1989). White privilege: Unpacking the invisible knapsack. Peace and Freedom, 10-12.

McLaughlin, N. (2004). Out of wonder: The evolving story of the universe. Dublin: Veritas.

O’Toole, L. (2008). Understanding and taking into account individual patterns of learning – Implications for the well-being of students and teachers. European Journal of Education, 43 (1), 71-86.

Page, S. (2007). The difference: How the power of diversity creates better groups, firms, schools, and societies. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Pearsalla, H. & Pierce, J. (2010). Urban sustainability and environmental justice: Evaluating the linkages in public planning/policy discourse. Local Environment: The International Journal of Justice and Sustainability, 15(6).

Portney, K., (2003). Taking sustainable cities seriously: Economic development, the environment, and quality of life in American cities. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

| Taylor, D. E. (2000). The rise of the environmental justice paradigm injustice framing and the social construction of environmental discourses. American behavioral scientist, 43(4), 508-580. |

Simonton, D. K. (1999). Origins of genius. New York: Oxford University Press.

Zhang, Y., Baral, A., & Bakshi, B. R. (2010). Accounting for ecosystem services in life cycle assessment, part II: Toward an ecologically based LCA. Environmental Science & Technology, 44(7), 2624-2631.

Matthew Kolan is a Senior Lecturer at the Rubenstein School of Environment and Natural Resources at the University of Vermont.

Kaylynn and Matt often work together on consulting projects and collaborative teaching, learning, and research endeavors where they actively engage with the generative tension that arises from their own differences. They have been working together and experimenting with the framework described in this paper for over 6 years in a variety of intercultural facilitation contexts. The authors can be reached at matthew.kolan@uvm.edu and ktwotrees@gmail.com.

Matthew Kolan is a Senior Lecturer at the Rubenstein School of Environment and Natural Resources at the University of Vermont.

Kaylynn and Matt often work together on consulting projects and collaborative teaching, learning, and research endeavors where they actively engage with the generative tension that arises from their own differences. They have been working together and experimenting with the framework described in this paper for over 6 years in a variety of intercultural facilitation contexts. The authors can be reached at matthew.kolan@uvm.edu and ktwotrees@gmail.com.  Kaylynn Sullivan TwoTrees is an artist, educator, activist, and part-time Lecturer at the Rubenstein School of Environment and Natural Resources at the University of Vermont.

Kaylynn and Matt often work together on consulting projects and collaborative teaching, learning, and research endeavors where they actively engage with the generative tension that arises from their own differences. They have been working together and experimenting with the framework described in this paper for over 6 years in a variety of intercultural facilitation contexts. The authors can be reached at matthew.kolan@uvm.edu and ktwotrees@gmail.com.

Kaylynn Sullivan TwoTrees is an artist, educator, activist, and part-time Lecturer at the Rubenstein School of Environment and Natural Resources at the University of Vermont.

Kaylynn and Matt often work together on consulting projects and collaborative teaching, learning, and research endeavors where they actively engage with the generative tension that arises from their own differences. They have been working together and experimenting with the framework described in this paper for over 6 years in a variety of intercultural facilitation contexts. The authors can be reached at matthew.kolan@uvm.edu and ktwotrees@gmail.com.