O Grows, Community-Based Food Systems, and the Sustainability Compass

Forbes Andrzejewski JSE General Fall 2019 Issue PDF

Link to the JSE Fall 2019 General Issue TOC

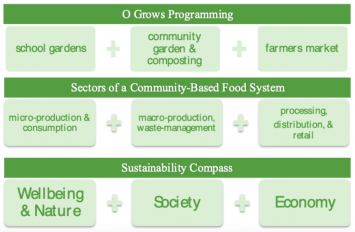

Abstract: This program feature documents our reflections on how the work of O Grows, is, or more accurately has become, increasingly sustainability-oriented. O Grows is a non-profit, community-university partnership with the mission to leverage the local capacity in service of community food needs. Specifically, we focus here on how engagement with an increasing number of sectors of the local food system, as we work toward this mission, has demonstrated a commensurate increase in alignment with the cardinal directions of the sustainability compass—attention to Nature, Society, Economy, and Wellbeing. We have realized, as O Grows has evolved, that keeping the program going and attending to sustainability are one and the same. As such, we argue the sustainability compass is a useful heuristic not only for reflection after-the-fact but also for partnership planning.

Keywords: Food security, local food system, community-university partnership, reflective practice, sustainability compass

In the spring of 2017, the Office of Sustainability at Auburn University recognized O Grows, a community-university partnership, for making significant contributions toward sustainability with the Spirit of Sustainability Award. As university members of this partnership that seeks the creation of a sustainable community-based food system, we pride ourselves and our collaborators on being sustainability-focused. Receipt of the award prompted us to reflect on what our organization’s focus on sustainability has meant in practice. Our university, as with many organizations worldwide, uses the Sustainability Compass (Atkinson, Dubourg, Hamilton, Munasinghe, Pearce, & Young, 1997) to provide a shared definition of sustainability. Like a regular compass, the Sustainability Compass (see Figure 1) orients users using the points N, S, E, and W. But instead of North, South, East, and West, the Sustainability Compass uses Nature, Society, Economy, and Wellbeing to map the domains of sustainability. To frame our reflective work, we have done the same.

Figure 1. Sustainability compass

This article documents our reflections on how the work of our partnership is, or more accurately has become, increasingly sustainability-oriented. Specifically, we focus on how engagement with an increasing number of sectors of the local food system has demonstrated a commensurate increase in alignment with the cardinal directions of the sustainability compass for O Grows.

For clarity, for the duration of this manuscript we will adopt the convention of using ‘we’ when we are referring to ourselves, the authors, and we will use ‘the partnership’ to describe broader participation in O Grows efforts.

What is O Grows?

O Grows is a community-university partnership among a local school district, civic organizations, the Food Bank of East Alabama, and Auburn University [AU]. Located in Opelika, Alabama, the county seat of Lee County, O Grows has a mission to address food insecurity through the development of a community-based food system. In support of this aim and in collaboration with 100+ residents that represent the social and economic diversity of the areas, O Grows directs a school garden program; the Opelika Community Garden; and Opelika’s seasonal, state-certified farmers market from our headquarters at the Southside Center for the Arts. Through these efforts and related programming, O Grows has donated over 15,000 pounds of produce in the fight against local hunger, facilitated the commerce of small-scale local farmers to thousands of customers, and promoted career readiness skills to hundreds of the area’s most marginalized students. Our vision is the creation of a sustainable community-based food system, where food production, processing, distribution and consumption are integrated to meet the food needs of all residents in ways that are economically, socially, and environmentally viable for future generations.

What are the Sectors of a Community-Based Food System?

The trajectory or O Grows’ efforts to date—school gardens to the community garden to the farmers market—is emblematic of a growing recognition that meeting the food needs of community members depends on identifying shared value among all sectors of the food system. Food systems vary in their size and scope but all food systems involve the people and processes that move food from “farm to fork,” including production, processing, distribution, retail, consumption, and waste management (UNEP, 2016).

Production—growing or raising of food products

Processing—cleaning, packaging, value-added products (e.g., breads, jellies)

Distribution—transportation of food products to markets

Retail—food businesses (e.g., grocery stores, restaurants)

Consumption—meal preparation and eating

Waste Management—recycling and disposal of resources

In the last several decades food systems have moved toward industrialization, leaving community members increasingly disconnected from their food. In the 1800’s 90% of Americans lived on farms. By 1900 40% did so. Today, it’s less than 1% (Dimitri, Efflin, & Conklin, 2005; Fuglie, Clancy, Heisey & Macdonald, 2017). Most Americans cannot identify the places of origin for the food they consume (Hart, Bishop, & Truby, 2002; Cairns & Johnston, 2018). This is borne out in our data from younger students that show it’s relatively common for them to answer the question “Where does food come from?” with “Grocery store” or “Restaurant!” This is not to suggest that the globalization of food systems is without merit, rather that industrial agriculture and small farming each have a role to play.

Lee County and the city of Opelika reflect the state and national trend of communities that are unable to meet local food needs through self-reliance alone. With only 5% of county land available for agricultural use, commercial agricultural production accounts for a small percentage of the local economy. Of this area only 13% is harvested (Meissner, 2012). With an average annual income of $5,500, most farmers in Lee County see generally small production output. Unable to meet the volume and timing of local retail outlets and restaurants, most sell their products at local farmers markets and roadside stands (Meissner, 2012). Meanwhile, consumers are forced to rely on non-local sources for their food needs. Such situations exacerbate the condition of residents living with food insecurity in any community.

Community food systems offer a counter to some of the sustainability pressures brought by national and global food systems. Different communities have different food needs (and interests) but in all community food systems the six food sectors work to achieve shared benefit through a shared value in meeting the specific food needs of a community—consumers get access to the freshest possible foods and know where it comes from, and small and medium scale farmers have more direct access to and knowledge of local markets. And, as proximity allows for familiarity and greater cooperation the success of one food sector depends on the success of others. That is, meeting the food needs of a community is not limited to making sure people aren’t hungry. Instead community food systems improve the social and economic health of identified areas by making foods available, accessible, and useable to all residents and by workers earning sustainable wages.

What is the Sustainability Compass?

With alignment to the four cardinal directions, the Sustainability Compass draws our attention to the ways in which achieving sustainability requires consideration of concerns related to Nature, Society, Economy, and Wellbeing (see Figure 1). Using the compass as a reflective tool quickly revealed the ways in which these four directions are interrelated and interdependent.

Mapping the Work of O Grows to Food Sectors and the Sustainability Compass

As already mentioned, receipt of a sustainability-focused award at our university prompted us to ask the question: How is our work about sustainability? When we thought through our history as an organization, we recognized that our explicit focus on the inclusion of more food sectors in our partnership led us to work that was more attentive to the four cardinal directions of the sustainability compass (see Figure 2). We have articulated that growth in the following sections organized around the phases in the evolution of O Grows and the sustainability compass points:

Nature—protection and restoration of the physical environment.

Society— connectedness among groups of varying norms and conditions.

Economy—viable and inclusive financial prosperity.

Wellbeing—personal health and overall quality of life.

The Evolution of O Grows as a Community-Based Food System

Phase 1: Consumption and Self-Sufficient Production

What came to be known as O Grows began in 2012 as a service-learning partnership between second-grade teachers and students at Southview Primary School, in Opelika City Schools [OCS] and Sean’s undergraduate educational psychology course in the College of Education at AU. Assisted by other parents at the school, Sean and his undergraduate teacher education students installed a garden and implemented a year-long garden curriculum to promote outdoor education. The students’ harvest provided more vegetables than needed for the end of the year salsa party they had planned. Undirected, the second graders decided it should be donated to the food bank and their AU mentors arranged for Elsie Lott (Board Member and Manager of the Community Market) to come to the next class period and accept the donation on behalf of the Food Bank of East Alabama. The donation was a little more than 20 pounds. Yet, for project leaders the experience suggested that school gardens had more potential than first imagined.

By the end of the school year, several other schools in the district expressed interest in joining the group. As exciting as the spread of interest among schools was, expanding the collaboration would require additional resources. Sean met with his department head and she encouraged the expansion, agreeing to fund two graduate students to assist with the project. A call was then put out to solicit interest among AU faculty and, thankfully, faculty from the College of Education and the College of Agriculture responded.

Accordingly, additional faculty (and their students) from the AU Colleges of Education and Agriculture got involved, Carey, among them; their expertise was needed to sustain the growing efforts in the schools. The work of faculty was practical (e.g., horticulture), conceptual (e.g., curriculum mapping), and methodological (e.g., participant recruitment and data collection), while AU students actively participated in the creation and renovation of school gardens and assisted OCS faculty with site-specific programming.’

Soon after, the AU group met with school district representatives to discuss the partnership’s future. The conversation began by reaching consensus that the goal of the partnership was to promote school gardens as outdoor classrooms. However, it was also agreed that each school had unique interests so the partnership would not merely replicate what was done at Southview. A couple of the schools simply wanted to have a garden installed. Others expressed interest in working with AU faculty and students to develop programming. Stakeholders agreed that university faculty would work alongside each school partner to get the school gardens installed and programmed if necessary. After that, schools would assume increasing responsibility for garden maintenance and relevant instruction.

In the fall of 2013, efforts continued at Southview Primary School and began with faculty and students at Northside Intermediate and Opelika Middle School. With a year of experience behind them, the second-grade teachers at Southview were comfortable taking lead on garden instruction, but AU faculty were present at weekly class meetings to assist. At Northside Intermediate, the gifted teacher had an existing but under-utilized vegetable garden and was interested in developing semester-long garden instruction. At Opelika Middle, a special education teacher wanted to update an overgrown courtyard in the school, establish an accessible vegetable garden, and implement programming for her students with physical disabilities. AU faculty and students worked with the teachers and students at each school to install or update the gardens during the first part of the semester and lead weekly lessons.

By January of the next year and with the other school garden programs afloat, attention turned to two other district schools, Morris Avenue Intermediate, where the partnership installed a fruit and fitness trail, and West Forest Intermediate, where the partnership installed a butterfly garden. The interested teachers at each school did not need assistance with programming, so efforts were focused on the installation of gardens during the first couple of weeks of the semester.

The third school, the Opelika Learning Center (OLC) was the last school to join the partnership. OLC serves as the local alternative school, enrolling children in grades 3-12 who have been identified with behavioral issues that place them academically and/or socially at-risk for dropping out. The consumer science teacher and her students at OLC were interested in installing a school garden as part of their class (grades 9-12). Several of the students were familiar with the fundamentals of vegetable production and eager to work in the garden while others were more familiar with or interested in how to use food (i.e., cooking, nutrition). The teacher had no experience with gardening, so the partnership worked with her and her students to design activities to integrate the garden into their class activities. Instruction focused on areas of student interest. Each student grew their own row of crops, and local chefs were recruited to come to the school each week to work with the students to prepare and preserve low cost, high nutrition meals (Forbes & Andrzejewski, in press; see Table 1 for a summary of school-based O Grows initiatives).

Table 1

School Grades School Leaders Type of Garden AU Action

| Southview | 2 | 2nd Grade Teachers | Vegetable | Maintenance support |

| Northside | 3-5 (Gifted) | Gifted Teacher | Vegetable | Installation;

Instructional support |

| Morris Avenue | 3-5 (P.E.) | P.E. Teacher | Fruit and Fitness Trail | Installation;

Maintenance |

| West Forest |

3-5 (after-school program) |

Afterschool Program Director | Butterfly Garden | Installation;

Maintenance |

| Opelika Middle | 6-8 (Self-contained S.E.) | S.E. Teachers | Produce and Ornamental | Installation- improvement;

Instructional support |

| Opelika Learning Center | 9-12 | Consumer Education | Produce | Installation;

Instructional support |

Wellbeing and Nature

With a goal to promote awareness of local food and food self-sufficiency, O Grows started in 2012 at Southview Primary School, a PK-2 school in Opelika, Alabama. As previously mentioned, efforts there began with the installation of a small garden in a previously unused outdoor space. Students worked with local volunteers as they prepared the beds, grew produce, and donated a portion of their harvests to the local food bank. Over the next two years, outdoor learning spaces were installed at five other schools in the system. These efforts were primarily focused on the consumption sector of a community-based food system with a secondary, albeit requisite, focus on production. That is, our aims were for students to participate in outdoor learning spaces, engage in food production on a small scale (see Figure 3), develop an appreciation for the sources of nutritious food (i.e., direct their attention away from retail and toward production), actually consume fresh produce, and make fresh produce available to their most vulnerable neighbors via donations to the food bank. With the benefit of hindsight and a growing awareness of sustainability as an ideal, we realized these efforts afforded us opportunities to attend to Wellbeing (i.e., “Our individual health, happiness, and quality of life” Atkisson & Hatcher, 2001) through production and consumption of nutritious food and Nature (i.e., “All of our natural and ecological systems and environmental concerns, from ecosystem health and nature conservation, to resource use and waste” Atkisson & Hatcher, 2001) through the use of outdoor learning spaces.

Figure 3. Students at a school garden site show what they are growing

Phase 2: Consumption, Production, Waste Management, and Distribution

When work began with OLC, the partnership expected things to go much as they had with the other schools. After the garden and related programming were established, the plan was to move on to other schools in the area that were interested in the same. Instead, the OLC experience alerted us to a community challenge that initiated a sea change in the partnership between OCS and AU.

Aware of the link between students referred to alternative schools—a last option for K-12 students whose academic and social needs were not met in traditional environments—and living near or below poverty level (Porowski, O’Conner, & Luo, 2014), it was expected that students identified as low income would be disproportionally represented at OLC. It was surprising, however, that the figure was, and continues to be, 90%; at no other school where the partnership worked with students was the percentage above 50%. Less surprising was learning that many of the OLC students were experiencing or had experienced food insecurity, a condition marked by insufficient access to the nutrition needed to live active and healthy lives (Coleman-Jensen, Gregory, & Singh, 2014)

Some of the information came from our school partners but most of it came from the students themselves. Through class discussion, casual conversation, and journal entries students revealed instances of their families having financial pressures (e.g., loss of income, medical bills) that forced a tradeoff between other basic needs (e.g., housing, utilities, medical care) and adequate nutrition. As the students contextualized the impact of food insecurity, it was impossible to ignore that the gross majority of students lived in one of two Opelika neighborhoods, Carver or Jeter. These historically African-American neighborhoods have long been two of the five communities most vulnerable to food insecurity in our area (U.S. Census Bureau American Community Survey, 2010). The majority of residents are low-income; poverty and unemployment rates are higher than city, state, and U.S. averages. Food self-reliance is near zero and consumers are divorced from other food sectors, with the exception of retail. These are exacerbated by the need for residents to access food support outside of the Carver and Jeter communities. With only one grocery store within the Carver and Jeter areas, convenience stores are the near exclusive retailers that accept federal program benefits. One food pantry with a soup kitchen operates in the Jeter area and serves 60 residents one day per month. Most low-income residents receive food assistance by accessing food retailers, food pantries, and soup kitchens that are located more than five miles from their homes, of which the most stable is the Community Market of the Food Bank of East Alabama (Lee County Community Food Security Assessment, Meissner, 2012).

What was learned about the food needs of Carver and Jeter residents was stunning. And, frankly, we were embarrassed that though we were well aware of the links among food insecurity, low socioeconomic status, and being placed at risk for school failure, we had not adequately considered these relationships in context with regard to the students with whom we worked at OLC. At the same time, it was powerful to see students who are typically marginalized recognize their ability to affect a community challenge. The garden at OLC is the largest of the school produce gardens and coupled with the physical and emotional maturity of teen-agers over pre-adolescents, food production is substantially greater at OLC than total production for all other school produce gardens (e.g., 615 pounds vs. 110 pounds in spring 2014). More still, for the students at OLC who live with food insecurity, their actions were an expression of agency against a potential barrier to their future success.

Our learning about the food needs of many of the students at OLC coincided with the release the of the Carver and Jeter Community Planning Initiative. The initiative was commissioned by the City of Opelika in 2012 to conduct a comprehensive visioning and planning process for land use, public services, and economic development for the Carver and Jeter neighborhoods. In March 2014, the group had published the findings of their efforts in “The Carver-Jeter Plan.” The report identified food security among the areas most significant concerns [in line with U.S. Census Bureau American Community Survey (2012) data] and called for the development of a community food project in response.

The OLC experience was transformative for the partnership. Greater still, our experiences there in conjunction with the findings of “The Carver-Jeter Plan” alerted us to the extent of local food insecurity and contextualized the impact it has on students. Our response to this new awareness was to seek out community partners. Mindful of the role that the Food Bank of East Alabama played in attempting to meet local food needs, Sean suggested that the Food Bank of East Alabama join our partnership. One of the school leaders identified Keep Opelika Beautiful [KOB] as another potential partner. KOB had an existing relationship with OCS, promoting environmental stewardship. With unanimous support from existing stakeholders, invitations were extended to the food bank and KOB. They accepted and joined AU and OCS under the new banner of O Grows.

Community Garden. Members of the Carver and Jeter Community Planning Initiative invited representatives from O Grows to meet with them and representatives from Envision Opelika, a non-profit community development corporation. At the meeting, the director of the Envision Opelika, who was also a former city mayor, described how Envision Opelika and its partners had been transforming a former school, located at an intersection of the Carver and Jeter communities, into the Southside Center. The center boasts a 300-seat auditorium and includes four acres, two on the front and two on the rear of the building. At that time, the center was only home to a local arts council and a community theater company, but upon completion of the renovation, the remaining space was planned for lease by community based non-profit organizations. She mentioned how Envision Opelika had committed a portion of the building and green space at the Southside Center for use in moves toward a community-based food system. It was then that Envision Opelika asked if O Grows would take the lead on the creation and management of a community garden at the Southside Center. O Grows took on this challenge with optimism about the avenues it would create to continue involving OLC students.

As most of the OLC students live in the neighborhoods around the Southside Center, the community garden provided opportunities for them to be engaged during weekends and school breaks. Better still, the OCS superintendent supported the idea of getting students into the community and committed to creating a separate class for the garden program—a food systems class—funding a teaching position and transportation to the community garden two days a week. With the school district on board, other organizational partners provided needed resource. KOB absorbed the cost of the necessary liability insurance coverage. Our AU department head began a yearly budget allocation for the community garden and graduate student support. And, the Food Bank of East Alabama agreed to take as much donated produce as could be grown, targeting distribution to those in the Carver and Jeter communities.

After quick visits to a few community gardens in the region, a blast of publicity, and several impromptu meetings, new and old O Grows members converged on a 10,000 square foot piece of greenspace at the Southside Center. AU’s Department of Horticulture sent staff and heavy equipment to clear and prepare the ground. A fence contractor and resident of the Carver neighborhood donated the materials and labor for a picket fence to secure the area. And, in the brutal heat of early summer, the Opelika Community Garden opened its gates.

In the first year, 26 residents secured plots in the community garden, six of whom identified as low-income, which was representative of the broader Opelika community. Plots were made available for lease, with fees waived for food bank clients.

O Grows volunteers, including OLC students, maintained soil quality, irrigated the plots, and maintained the newly installed composting area. An eighth of the garden space was reserved for the students in the OLC food systems class. Gardeners were encouraged to add a portion of their harvests to the produce donated from the students’ plot. By year’s end, O Grows donated 1,100 pounds of produce to the Food Bank of East Alabama from the community garden, in addition to facilitating greater food self-sufficiency for our resident gardeners and OLC students.

In successive years O Grows has made significant strides in attempting to meet local food needs through the community garden. While there hasn’t been a significant increase in the number of resident gardeners, O Grows has more than doubled its average annual donation since the first year of the community garden with over 15,000 pounds to date. A major factor in production has been the addition of a 30’x90’ greenhouse. In the simplest of terms, the greenhouse provides more workable space. O Grows uses much of the space for hydroponic (i.e., drip bucket and deep-water culture) gardening. These methods allow for typically greater volume and quicker harvests compared to traditional gardening. The rest of the area contributes to increased production by extending the outdoor growing season. With greater environmental control, plants can be started in the greenhouse weeks before, or after, a seedling could survive outdoors. Improvements to the outdoor garden increased production, as well. An irrigation system installed in the second year of the community garden provided a consistent amount and coverage for plants, replacing the hand watering method used in the first year. Soil condition improved with the introduction of amendments such as a chicken and cow manure obtained from local farms.

Of course, the ultimate cause of the increased production has been the interest, expertise, and generosity of individuals who have come to the community garden. With each new year there are new opportunities to do better than the year before. Moreover, the connections made with community members and organizations stimulated many of these opportunities. Since opening the community garden, O Grows has received over $40,000 in financial support from community grants, local business sponsors, and individual donations. Public awareness has grown as well, bringing groups including the Lee County Master Gardeners, AU’s Horticulture Club and Collegiate FFA, and Lee County Cooperative Extension agents to assist with the community garden.

But, of all the groups who have contributed to the community garden and mission of O Grows, none has had a greater impact than the OLC students who have become paid members of the O Grows staff. In 2015 and 2016, we were awarded Competitive Outreach Scholarship Grants by AU’s Office of Outreach to employ 4 OLC students with O Grows during non-school hours at a rate of $10 per hour. The student employees received training in vegetable production that reflects Alabama’s College and Career Ready Standards. They joined AU graduate students as the only paid staff and assisted volunteers with all aspects of O Grows programming. From the end of the second grant period, AU’s Vice-President for Outreach allocated $10,000 a year for on-going support of the effort. Beyond the opportunity for a pay check, the majority of students hired build greater social connections to and within their community resulting in general social skills (e.g., increased school attendance and engagement, fewer disciplinary referrals, improved soft skills) and task-specific employment skills.

Society

With O Grows having established a presence in the community through the installation of five school gardens, the city offered space at an underutilized community center to install a community garden (see Figure 4). The community garden was designed with a dedicated space for composting, which prompted us to redouble our efforts to compost at the school-based spaces. Doing so afforded us an opportunity to meaningfully incorporate the waste management sector of the community-based food system. The community garden also provide space for community residents to be outdoors and observe and nurture living systems, in much the same ways the school spaces had provided for students. The community garden space also includes spaces for animals: goats, chickens, ducks, and bees. That is, it enhanced our commitment to Nature and Wellbeing. Moreover, the community garden space allowed for the introduction of retail, via O Grows’ sales to local food businesses. Inasmuch as O Grows is fundamentally a university-community partnership, it represents the ways in which institutions have come together and collaborated around community-based food systems and food security. We now see our growing involvement with schools, community residents, local businesses as attending to Society (i.e., ‘the institutions, organizations, cultures, norms, and social conditions that make up our collective life as human beings”; Atkisson & Hatcher, 2001).

Figure 4. Residents tending to their plots at the O Grows Community Garden

Phase 3: Consumption, Production, Waste Management, Distribution, Processing, and Retail

In early 2016, city leaders sought new management for the seasonal, state certified farmers market that has been in operation since the 1980’s. The market was originally located at the courthouse square and managed by the director of downtown development. Though successful, parking became an ever-increasing challenge, and the involved parties reached the shared decision that a move needed to be made.

By this time the community garden (and related work with OLC) had been in operation for two full years. With the help of the OLC students and student interns, O Grows made strides in meeting its mission via food donations and opportunities for residents to increase their food self-sufficiency. But with less than 1% of Carver-Jeter residents identified as low-income participating in the community garden, O Grows partners looked for ways to extend existing efforts. So, proposing that such a move would provide greater access to food resources among low-income residents and increased employment experience for OLC student interns, O Grows lobbied and received the opportunity to assume management of the Farmers Market and relocate it to the Southside Center. The attempt was supported by Envision Opelika’s pledge to provide liability insurance coverage for the effort. By season’s end in September 2016, the relocated farmers market drew an average weekly attendance of 260 customers while farmers reported revenues on par or above the previous year, all while reducing barriers to accessibility for residents of the Carver and Jeter Communities.

As had occurred with O Grows at OLC, the experience of managing the farmers market pushed stakeholders to appreciate that the well-being of any consumer is intimately linked to the other parts of the food system (producers, distributors, processors, retailers, and waste management and recycling). And, after that first year, we realized that O Grows had the capacity to embrace a larger mission. O Grows still works to access the potential of human capital and capacity to address local food security but now these efforts are more and more clearly focused on building and sustaining a community-based food system. It is impossible to work with farmers, consumers, gardeners, food banks, and local food businesses without developing a deep appreciation of the capacity for change in both the individuals and the relationships that give shape to a sustainable community-based food system.

Economy

Maintaining and growing the community garden and the community interest in the community garden space required that the partnership more explicitly attend to the (potential) economic impacts of O Grows’ work—Economy (i.e., “The human systems that convert nature’s resources into food, shelter, ideas, technologies, industries, services, money and jobs”, Atkisson & Hatcher, 2001). Specifically, a paid internship program for students at the local alternative school was started, and the city asked that the partnership move the local farmers market to the community center that also houses the community garden (see Figure 5). The farmers market provides an opportunity for local vendors, including O Grows, to sell their produce and crafts.

Life for students living in poverty consistently predicts (a) food insecurity and (b) failure to complete K-12 education at significantly greater rates than those students not living in poverty. Despite the challenges of disentangling cause and effect across generations, food insecurity during a child’s K-12 years increases the likelihood that he or she leaves school without a diploma, threatening the student’s future wellbeing (Aud, Wilkinson-Flicker, Kristapovich, Rathbun, Wang, & Zhang, 2013). Consider that students who fail to finish high school earn nearly $700,000 less in their lifetime compared to those who complete high school. Moreover, these students add over $250,000/person more in costs to the national economy in their lifetime than students who complete high school due to lower tax contributions, higher reliance on Medicaid and other assistance programs, and greater involvement in the criminal justice system (Aud et al, 2013).

Figure 5. Farmers and consumers come together at the O Grows farmers market

Conclusion

As we traced the history and accomplishments of our partnership, we can see a move from a focus on self-sufficiency, as seen in the school garden efforts, to a focus community-based food system, which, we have learned, required a focus on sustainability. As that shift occurred, there was a commensurate shift from focusing on wellbeing with a touch of nature to the inclusion of economic and societal concerns.

To be clear, understanding our work in relationship to the sustainability compass is post-hoc, based on retrospective and reflective analysis. That is, in part, because the partnership was not initially explicitly sustainability-focused. The partnership was motivated to keep the project going and growing but by connecting with an increasing numbers of food sectors O Grows has been able to sustain its efforts by attending to the cardinal directions of the sustainability compass. Since the award, the partnership has more intentionally aligned its efforts with the compass, realizing that keeping the program sustainable and attending to sustainability are one and the same.

We have come to see the sustainability compass as heuristic for planning, rather than as just a heuristic for reflection. That is through an increase in the number of food sectors involved in O Grows’ community food security efforts we have come to recognize how improving the local food system requires attention to the inter-related points of the sustainability compass. To this end we and the others of O Grows have turned our attention to the fact that the efforts of the school garden, community garden, and farmers market exist largely independent of each other. Currently, O Grows is planning a food summit to better integrate these efforts and promote sustainable community food security. The proposed summit will engage local members of every food sector to develop an area-specific action plan to leverage and link existing efforts. Objectives and activities of the plan will be grounded in the framework of the sustainability compass and demonstrate shared value among sustainability efforts for nature, society, economy, and well-being in community food security gains.

Through this post-hoc explanation of how the sustainability compass maps onto O Grows efforts our hope is that our stumbling into sustainability is instructive for others interested in engaging local food systems. Use of the sustainability compass supports identifying potential community partners and provides parameters by which success in achieving sustainable improvement among local food systems can be assessed. Greater still, the compass serves as a touchstone to demonstrate the inter-relatedness of each sector, offering a shared vocabulary and ethos among community partners from different sectors, in achieving community food security that is sustainable.

References

Atkinson, G., Dubourg, R., Hamilton, K., Munasinghe, M., Pearce, D., & Young, C. (1997). Measuring sustainable development: macroeconomics and the environment. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Atkisson, A., & Hatcher, R. L. (2001). The compass index of sustainability: Prototype for a comprehensive sustainability information system. Journal of Environmental Assessment Policy and Management, 3(04), 509-532.

Aud, S., Wilkinson-Flicker, S., Kristapovich, P., Rathbun, A., Wang, X., & Zhang, J. (2013). The Condition of Education 2013. NCES 2013-037. National Center for Education Statistics.

Cairns, K., & Johnston, J. (2018). On (not) knowing where your food comes from: meat, mothering and ethical eating. Agriculture and Human Values, 1-12.

Coleman-Jensen, A., Gregory, C., & Singh, A. (2014). Household food security in the United States in 2013. USDA-ERS Economic Research Report, (173).

Dimitri, C., Effland, A., & Conklin, N. C. (2005). The 20th century transformation of US agriculture and farm policy (No. 1476-2016-120949).

Forbes, S. A., & Andzrejewski, C. E. (in press). O Grows and the Contextual and Interactive Model of Community-University Collaborations: A (re)incarnation story. In F. Kochan, & D. Griggs (Eds.). Creating school partnerships that work: A guide for practice and research. Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing.

Fuglie, K., Clancy, M., Heisey, P., & Macdonald, J. (2017). Research, productivity, and output growth in U.S. agriculture. Journal of Agricultural and Applied Economics, 49(4), 514-554. doi:10.1017/aae.2017.13

Hart, K. H., Bishop, J. A., & Truby, H. (2002). An investigation into school children’s knowledge and awareness of food and nutrition. Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics, 15(2), 129-140.

Meissner, E. (2012). Lee County Food Security Assessment. Alabama Agricultural Experiment Station Bulletin, 678, 1-58.

Porowski, A., O’Conner, R., & Luo, J. L. (2014). How Do States Define Alternative

Education? REL 2014-038. Regional Educational Laboratory Mid-Atlantic.

UNEP (2016) Food Systems and Natural Resources. A Report of the Working Group on Food Systems of the International Resource Panel.

U.S. Census Bureau American Community Survey (2010). American Community Survey 5 Year Estimates. Washington, D.C.