Learning in the Struggle: Reframing Economic & Environmental Justice

PDF: Jan BreidenbachSpring2013

Abstract: The dominance of neoliberalism over the past 35 years has transformed not only how global cities develop but also has shaped new forms of activism that contest this very development, including both economic and environmental justice organizing. Many of these social movement groups have developed similar models of organizing (community mobilization, policy advocacy and—when necessary—litigation) that target the skewed distribution of urban development and land uses. As in all social movements, they also “frame” their work to attract support and blunt opposition, a process that is part of the educative function of organizing. Recently, as these economic/environmental justice organizations have grown and matured, many are combining their frames, seeing the relevance of both frames to their communities. This process of framing and reframing through active organizing is one of learning in the struggle.

The essay has two parts. The first describes a conflict in a Los Angeles community between the need for affordable housing (an economic justice demand) and the need to reduce exposure to freeway pollution (an environmental justice demand). Based on years of data, policymakers in LA County limited affordable housing near freeways—and considered banning all housing in these “buffers”. County health officials considered the issue one of environmental justice; local activists rejected it as sacrificing economic justice. Highlighting one economic justice group out of a larger multiple-case study, we explore how the activists learned from this struggle, adapting environmental justice into their ongoing work and organizing frames. The second part of the essay situates this combined frame in a range of social movement “justices”. We give it the symbol EJ2 and create the term sustainable justice to identify it. We then explore the social meaning of sustainability, finding it too ambiguous to respond to the demands of disenfranchised urban populations. We argue that if sustainable justice inheres to the social meaning of sustainability,then sustainability has the potential of becoming a social movement frame. We conclude with an acknowledgement of the work of others who have attempted to theorize the importance of justice as a core meaning of sustainability.

Key words: economic/environmental justice,organizing frames/learning,sustainability/ sustainable justice

Yet we cannot do without the concept of justice for the simple reason that the sense of injustice has historically been one of the most potent seedbeds

of all to animate the quest for social change.

(David Harvey & Cuz Potter, 2009, 41)

Prologue

In 2008, the Los Angeles County Community Board of Supervisors determined that it would no longer invest its affordable housing funds in any subsidized shelter sited within 500 feet of a freeway. The reason: two decades of research had conclusively shown that living in this “buffer” increases the risk of low birth weight, higher rates of asthma, respiratory problems and cancers. Given that the majority of Angelinos living in the buffer are lower-income people of color, the proposal was posed as a question of environmental justice. However, justice organizers from Boyle Heights—the community with the greatest number of freeway miles crossing through it—did not (and do not) support the proposal. When asked why, they respond that it is a question of economic justice.

Geography Matters: Boyle Heights, Los Angeles

Boyle Heights is a small community in Los Angeles, just east and across the river from downtown. Originally the home of the native Tvonga (Estrada, 2008), the population grew when the Spanish conquered the land and built the San Gabriel Arcangel mission in 1771, then again with the establishment of the outpost El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora, la Reina de Los Angeles sobre el Rio do la Porciúncula in 1781. It became part of Mexico in 1821 after the Mexican Revolution, and was ceded to the United States in 1848 after the Mexican-America War. Although on the “other” side of the river,

Boyle Heights’ proximity to the growing Los Angeles downtown made it a gateway community for many immigrants and

migrants, the “Ellis Island” of the west coast.

Joining long-term Mexican residents, in the early 1900s Boyle Heights was a destination of choice for Japanese,

African American, Armenian and Italian newcomers, along with Midwestern Anglos looking for a new life in California and

Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe and the east coast[i] (JANM, 2005). By the 1930s, however, the Europeans and Midwesterners began to move to “better” neighborhoods on the west side of downtown; African-Americans moved to

join the Great Migration newcomers settling in the growing neighborhoods of Watts and Compton to the south. The Japanese left during World War II, rounded up and sent to concentration camps; virtually none returned to Boyle Heights (Estrada, 2008). By mid-century, the community had become what it remains today—a small (6.2 square miles) but dense (population: 100,000), low-income, predominantly Mexican and Mexican-American neighborhood known for cheap, crowded housing and polluted air (Figure 1) (Moore, 1991, 14, LA DCP, 2008).

Economic Justice in Boyle Heights: the Need for Affordable Housing

Boyle Heights is a poor community: the annual income for a family of four is less than $35,000/year and almost one-third of the residents live below the poverty line. Although high-density in terms of people per square mile, its housing stock is definitively low-density: mostly smaller apartment buildings and single-family homes, with over 80% of this stock built before 1970 and 42% constructed before 1940 (LA DCP, 2008). The combination of older, smaller housing units combined with an

average household size of almost four people/household results in 30% of the community’s families living in overcrowded conditions (more than one person/room) (City-Data, 2009, Boyle Heights Beat, 17 August 2012).

Local policy responses to the lack of “safe, decent, and affordable” housing in Boyle Heights have closely tracked federal trends. Public housing (built and managed by

the public sector) was proposed as national policy in 1937, but the first projects were soon transformed into wartime housing (Schwartz, 2010). Given Los Angeles’ strategic geography, six public housing projects were constructed in or near Boyle Heights for the purpose of sheltering the defense industry workforce. After World War II, two more projects were constructed before public housing as policy fell victim to “Red Scare” McCarthyism both nationally and locally (Parsons, 2005). No new public housing was built in Los Angeles after 1955. While most of the projects constructed during this window of progressive social policy are still standing and provide basic, if bare minimum, shelter for the poorest of the poor (public housing does not require a minimum income, as do other affordable housing programs), these homes suffer from disinvestment and lack of sufficient maintenance.

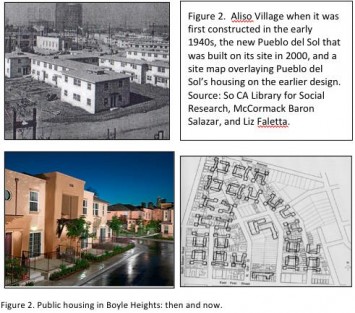

Since the 1990s, federal housing policy has encouraged the demolition and reconstruction of older projects to be replaced with less dense, mixed-income ones (NLIHC, 2012). In the early 2000s, Aliso Village, on the west side of the neighborhood, was torn down and rebuilt as Puerta del Sol, with for-sale townhomes targeted to the “high end” of “low-income” households, subsidized rental housing for the working poor and public housing units for the very poor (Figure 2, Aliso Village changes). While the new project is well built and attractive, the number of units available to the very poor was reduced—200 more were demolished than rebuilt—a source of frustration to economic justice advocates in the neighborhood (Cabildo, personal communication, September 12, 2012, Vilchis, personal communication, December 8, 2012).

Seventy percent of Boyle Heights families rent, considerably higher than the citywide average of 61%, and are somewhat protected rent control which requires rents increase at no more than four percent annually while the home is occupied. However, due the changes in state law in the mid-1990s, no California city can update its rent control ordinances from the original date of passage—L.A.’s was passed in 1978. Given the age of the housing stock in Boyle Heights, most rental units are included but the state law also requires “vacancy decontrol”: while rent increases are controlled for the duration of tenure, once a tenant moves, rents can be set at whatever the market will bear (LAHD, 2013). Thus, the protection that rent control provides also limits mobility.

Enter ELACC. In 1995, a group of community planners and affordable housing advocates formed the East LA Community Corporation (ELACC), with a vision of providing affordable housing and economic development opportunity on the “east side”. In the years since, ELACC has built almost 400 housing units, created opportunities for wealth/asset building through homeownership and small scale entrepreneurship and organized a membership cadre of community residents that take on public policy issues—mostly land use—important to their long-term vision of economic revitalization (ELACC, 2012).

ELACC’s mission of providing affordable housing has met many obstacles, however. With the neighborhood built out, there is little land available for affordable shelter (LA DCP, 2008). Further, in a cruel irony, local activists face the potential of unwanted attention—after decades of municipal inattention. The national planning trend towards denser cities with walkable neighborhoods, amenities, and access to transit has arrived in Los Angeles—with a vengeance (Nelson, 2011, Cortright 2009). Known by the planning appellations “smart growth”, “new urbanism”—and when developed around transit stations, “transit-oriented development” or TOD—this trend offers the environmental promise of lowering greenhouse gases (GHG) by reducing vehicle miles traveled (VMT) and reining in sprawl (ULI, 2010, Haas, et al, 2010). Certainly, these new urban neighborhoods have much to recommend them, but recent research finds that, particularly in TODs, there is a serious danger of gentrification and displacement[iii] (Chapple, 2009, Pollack et al, 2010, Dominie, 2012). In 2003, a new rail line opened joining downtown LA to Boyle Heights and beyond. Economic justice advocates rightly worry that long-term residents will be forced out (Serviss, 30 March 2011, Cabildo, personal communication September 12, 2012).

Environmental Justice in Boyle Heights: Near Roadway Pollution

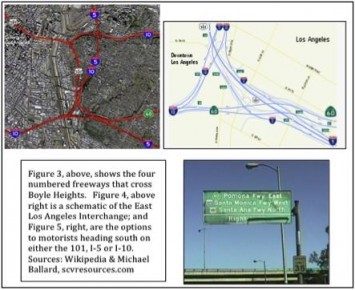

Four numbered freeways crisscross Boyle Heights (six if identified by their geographic names). Two are Interstates—the I-10 (San Bernardino and Santa Monica freeways), the I-5 (Golden State and Santa Ana freeways). Two are State highways, including the CA-101

(Hollywood freeway) and the CA-60 (Pomona freeway). These roadways barreled through the neighborhood over a period of two decades, slicing and dicing it so that people and goods could move more easily in and out of downtown and back and forth between the nearby industrial areas and the Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach, 25 miles to the south (Figure 3). At the crux of these freeways is the East Los Angeles Interchange, the busiest freeway interchange in the world (Figure 4). In spite of a plethora of signs seemingly every few feet, most drivers have little or no idea of the community they are racing through. Indeed, it can be hard to identify a sense of place when driving on this reticulated web of concrete (Figure 5). These behemoths dominate the physical space of the community they render apart, but even more importantly, the residue from their traffic volume creates a toxic soup that fouls the air and makes people sick.

(Hollywood freeway) and the CA-60 (Pomona freeway). These roadways barreled through the neighborhood over a period of two decades, slicing and dicing it so that people and goods could move more easily in and out of downtown and back and forth between the nearby industrial areas and the Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach, 25 miles to the south (Figure 3). At the crux of these freeways is the East Los Angeles Interchange, the busiest freeway interchange in the world (Figure 4). In spite of a plethora of signs seemingly every few feet, most drivers have little or no idea of the community they are racing through. Indeed, it can be hard to identify a sense of place when driving on this reticulated web of concrete (Figure 5). These behemoths dominate the physical space of the community they render apart, but even more importantly, the residue from their traffic volume creates a toxic soup that fouls the air and makes people sick.

In the 1990s, health researchers from the University of Southern California began studying the lung development of children living at varying distances from major roadways in 12 Southern California communities, the largest longitudinal investigation into pollution and child health in the United States. The communities included both dense urban cities and rural communities such as Long Beach (pop. 500,000) with its Port traffic, and Alpine in San Diego County (pop. 14,000) (Gauderman, et al, 2007, Cal-EPA, 2005). In the years since, over 100 peer-reviewed articles have been published from the study and building on its findings—including reports specific to Los Angeles and Boyle Heights (CARB, 2003, Hu et al, 2012, Perez et al, 2012).

The results are not pretty. Residential proximity to high-volume traffic and major roadways is associated with increased risk of low birth weight, higher rates of asthma and asthma exacerbations, respiratory problems—including decrease in lung function—and cancers. Importantly, while traffic pollution includes a range of gases and vapors, one of the most damaging contaminants is “particulate matter”, or PM, an ultrafine “dust” arising from road wear, diesel soot, combustion products, tire and brake abrasion, construction operations, and fires (there are two types: PM10 and PM2.5 , a finer subset). PM particles are easily inhaled, then deposited in the lungs where they cause permanent damage (Cal-EPA & CARB, 2005, SCAQMD, 2005).

The health impacts of traffic-related air pollution have been known for a long time; but more

importantly for planning and land use policy—and ultimately for justice organizers—were the findings that concentrations of traffic-related pollutants diminish dramatically with distance from the road. How much distance depends on a number of factors, but there is general agreement that severe health risk is reduced by over 60% at about 300 feet (100 meters) and by 80% at about 500 feet (150 meters) (Figure 6) (SCAQMD 2005).

The first major policy response to this chilling science occurred in 2003 when the California state legislature approved legislation banning future school construction within 500 feet from the edge of the closest traffic lane of any busy traffic corridor with a volume of 100,000 vehicles/day in urban centers or 50,000 vehicles/day in rural areas, as well as requiring mitigation for schools presently sited in the buffer (about 10% of all K-12 schools in the state) (SB 352, 2003).

Within a couple of years, concern spread to other land uses. In 2005, the South Coast Air Quality Management District (SCAQMD) published its Guidance Document for Addressing Air Quality Issues in General Plans and Local Planning (SCAQMD, 2005). The same year, the California Environmental Protection Agency and the California Air Resources Board published the Air Quality and Land Use Handbook: A Community Health Perspective (Cal-EPA & CARB, 2005). Both documents recommend that local jurisdictions and regional planning districts promulgate policies that limit “sensitive uses” and/or require mitigations for any sensitive-use development in the buffer. In addition to schools, these “sensitive” land uses now include childcare, senior day care facilities—and housing (see example, Figure 7).

The Conflict Between Housing and Pollution: Policy Responses

In January 2008 the LA County Community Development Commission (LACDC)—which oversees affordable housing production—proposed that LA County no longer invest public funds into subsidized housing in freeway buffer land; low-income housing could still be built in the buffer, but developers must find other funds—a difficult proposition at best. Subsequently, the County’s Public Health Department pushed the Regional Planning agency to ban all new housing in the buffer by rezoning the land non-residential in the upcoming revision of the General Plan (the LACDC has no land use authority and could only deny financing). Although community activists opposed the proposal, the Board of Supervisors passed it.[iv] As they

had with the LACDC proposal, community activists vehemently opposed the ban, arguing that it: a) would not help the 650,000 County residents presently living in the buffer; b) side-stepped the potential of mitigation strategies such as filtration systems, building materials/design, sound walls and vegetation barriers, as well as potential emission technologies; and c) does not take into account differences in topology, wind direction, etc. In addition to the planning issues, a complete ban would engender legal challenges; banning future use can reduce land values—a serious proposition in a nation where property rights trump virtually all others (Chung, personal communication, June 12, 2012, Chung, 2012, Houston, personal communication, October 15, 2012. On mitigation, see Cal-EPA & CARB, 2012, Houston, 2012).

Other jurisdictions in the region and the state are also looking at the problem. Since 2008, there are at least 10 other local governments addressing the problem of housing in the buffer (De Leon-Menjivar, C, 23 June 2011, Memo communication, Bailey & Hanning, Natural Resources Defense Council, 2011). In November 2012, the Los Angeles City Planning Commission approved an advisory notice for all sensitive use properties within 1000 feet of a freeway, noting that any development in the buffer poses health risks and residents should be aware of them (Bernstein, personal communication 8 January 2012). (Note: the City and County are completely separate in terms of land-use power, but the County can invest—or not—in affordable housing in certain parts of the City). The City’s decision in favor of an advisory rather than a ban reflects the fact that no community-based justice groups spoke in favor of a ban, having learned from one another that a ban was exchanging one injustice for another. As one planning commissioner noted: “Housing did not cause the pollution, it should not pay the price for it” (Cardoso, personal communication, January 8, 2013).

Re-framing Justice in Boyle Heights

Social movement researchers explore how social movements and the organizations that constitute them are born, grow and influence change. They illuminate how movements and their outcomes matter, along with how activists articulate messages to both recruit and educate their bases (members and/or represented constituencies), and blunt opposition. This educative process is one of “unpacking” ideological beliefs and commonplace frames of reference and “repacking” them to be expressed as a tactic, strategy or vision that “moves” the original belief in a new direction. This process is called framing and is part of the educative function of organizing, the “meaning work”—part of how organizers “learn in the struggle” they articulate, practice, reflect and re-articulate their messages, slogans and calls to action (Foley, 1999, Westby, 2002, Oliver & Johnston, 2000; for a discussion on the delicate relationship between organizing and educating, see Horton & Friere (Bell et al, Eds), 115-119).

Different types of frames are expressed at different scales and at different moments (Hall, 1996, 422). The broadest, movement-wide frames are known as “master frames”. Identified by Snow and Benford (1992), these are the closest to, and more identifiably derived from, movement ideology; e.g., the civil rights frame of the 1970s that has been appropriated by other movements, including the environmental justice movement (more on this below). Others suggest that master frames are more related to the strategic work of social movement organizing (Westby, 2002, 292). Clearly, master frames are movement wide, but framing can be as local as creating identify in a neighborhood (Martin, 2003). What is common at all scales is the use of narratives, concepts and even ideologies to “frame” collective action. The ultimate goal is to understand how this all plays out in the hurly-burly of daily organizing.

Learning in the Struggle

To illuminate how the hurly-burly actually happens, we return to ELACC and explore how its leaders learned from the clash of justices and how this learning is changing both the content and understanding of their work. Following the method of a multiple-case study with semi-structured interviews, talking with leaders at ELACC, other organizations, planning agencies, as well as university and foundation staff (Snow & Trom, 2002, Blee & Taylor, 2002). We highlight ELACC not only because of its focus on producing affordable housing, its firm opposition to any policy proposal limiting housing in the buffer, but also because its work is evidence of what is possible when economic and environmental justice are merged.

Although ELACC believes that mitigated housing should be permitted in the buffer, as an organization they recognize that the health impacts are dire and require a community response. Indeed, the issue is close to home for them. The ELACC office is a former Victorian house on South Boyle Avenue between the Santa Ana and Golden State freeways (both legs of I-5) just before these converge in the East LA Interchange—in two buffers! They are not just fighting for their neighbors, but for themselves as well. Since the first proposals to limit housing in the buffer were proposed in late 2007, ELACC organizing staff and members have been engaged in a learning process that connects their economic justice (housing) work to the need for environmental justice including working in community/university research projects on air pollution and participating in coalitions fighting for both economic and environmental justice.

In 2008 ELACC organizing staff and members participated in a “ground truthing” team, part of a foundation/university/activist collaborative analyzing the demographic patterns of air emissions in a number of LA communities, including Boyle Heights (Los Angeles Collaborative, 2010). This project researched the “cumulative impact” of air pollution—what happens when the poisons from a stationary sources—chrome-plating plants, tire recyclers and chemically intense manufacturing—interact with ambient vehicular pollution. The State of California is supposed to track all sources of non-mobile ambient air pollution but, not surprisingly, the activists found many sources that were not listed in the databases, indicating an exposure to a higher-than-estimated amount of pollutants. The results of these tests indicate that the air pollution problem cannot be resolved solely by limiting housing construction near freeways.

More recently, ELACC and other environmental justice activists also assisted university researchers from UCLA, USC and CARB (CA Air Resources Board) to understand the “UFP Cloud”—high counts of “ultrafine particles” including PM2.5, black carbon (soot), and nitrogen oxide (NO) (Pascual, personal communication, 20 September 2012). Researchers drove an electric car fitted with monitoring equipment through the major streets of Boyle Heights. The findings indicate that much of the pollution throughout the community (not only in the buffer) is from high “traffic density”, calculated as a ratio of streets to total land. Traffic density is a significant problem in Boyle Heights—not only are there many streets with short blocks with frequent stop signs/lights—but also when freeway traffic backs up, trucks leave the concrete ribbons and simply drive through the neighborhood. This constant stopping, idling and starting spews more pollution into the air, exacerbating the freeway contamination (Hu, et al, 2012).

In 2010, ELACC joined a two-year planning partnership supported by the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention’s Racial and Ethnic Approaches to Community Health for Communities Organized to Respond and Evaluate (CDC REACH CORE). The project, Turning Data into Action (TDA): Fighting Air Pollution in Two Immigrant Communities, prioritized two communities with the some of the worst air quality in the nation—Long Beach and Boyle Heights, chosen because they “bookend” the traffic pathway of goods movement from the Ports of Los Angeles/Long Beach to regional and national distribution centers. The TDA project taught community leaders to conduct health assessments, connect with residents, learn and understand available public health systems and conduct a “forces of change” assessment which identifies policy goals and strategies (Wallace, 2011, Wallace, n.d.). The project ended in December 2012, and according to ELACC organizing director, Mike Dennis, participating increased the technical skill level and sophistication of their membership, and enabled residents to integrate the new knowledge about the air they breathe with what they experienced from their daily round (Dennis, personal communication, 25 January 2013).

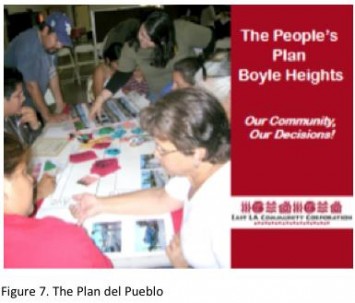

Working with their members, ELACC is actively engaged in crafting a community-based new Community Plan for Boyle Height.[v] The present Boyle Heights Community Plan (BHCP) dates from 1998 and is notable more for what it neglects than what it proposes. It highlights the need for affordable housing, but offers no blueprint to meet this need; recommends “preservation” of industrial land but has no mention of air quality, community health or the environment (BHCP, 1998). With the changes in regional transit, the BHCP is in the process of being updated. Not content to have this process occur without community input, ELACC is engaged in an educational and organizing effort to involve residents in drafting their own community plan—the Plan del Pueblo.

Working with their members, ELACC is actively engaged in crafting a community-based new Community Plan for Boyle Height.[v] The present Boyle Heights Community Plan (BHCP) dates from 1998 and is notable more for what it neglects than what it proposes. It highlights the need for affordable housing, but offers no blueprint to meet this need; recommends “preservation” of industrial land but has no mention of air quality, community health or the environment (BHCP, 1998). With the changes in regional transit, the BHCP is in the process of being updated. Not content to have this process occur without community input, ELACC is engaged in an educational and organizing effort to involve residents in drafting their own community plan—the Plan del Pueblo.

ELACC, along with any number of justice organizations—on the east side and elsewhere in the city—are working in coalitions and campaigns that are, indeed, combining both economic and environmental justice frames. Two of these: Clean Up, Green Up, and ACT-LA (Alliance for Community Transit-LA) have specifically identified economic/environmental justice as among their goals. Clean Up Green Up is a campaign to change city policy regarding regulation of industry pollution in Boyle Heights, Pacoima and Wilmington (two other pollution-

impacted communities (Clean Up, Green Up, 2012). ACT-LA is a new coalition that “roots itself in economic, environmental and racial justice” as it brings groups together to address the concerns of Los Angeles’ low-income/minority neighborhoods regarding land-use and transit policy—specifically the ramifications of the region’s vastly expanding fixed guideway railway system (ACT-LA, 2013, Yee, 2012).

According to ELACC Director of Organizing Mike Dennis, the takeaway from this—and other—work is that the residents themselves understand the “context of development”, including both economic and environmental dimensions. The changes in their work over the past few years have not detracted from their long-term mission of building and providing affordable housing, but have contextualized it with a greater understanding of land use and the built environment; and how these interact when it comes to shelter, health and justice.

EJ2 + Sustainability = Sustainable Justice

The right to the city is a like a cry and a demand…formulated as a transformed and

renewed right to urban life…as long as the

“urban” [is the] priority of use value

(Henri Lefebvre, 1996, 158)

In this section we first look at the rise and uses of specific “issue justices” that animate much social movement organizing, along with the most common, but indeterminate, frame of social justice. We do this to situate our primary interest, the merger of economic and environmental justice—to which we apply the symbol EJ2 (primarily for reasons of space) and give it the name of sustainable justice, alerting the reader of our intention to explore the relationship of justice to sustainability. We find sustainability on its own is lacking as a potential social movement organizing frame, it is simply too ambiguous and without any inherent implementation that would respond to the needs of those experiencing economic or environmental injustice. We delve further into the “three E’s” of sustainability—economy, environment, and equity—the “e-rubric” gateway into its complex dimensions, and explore how a frame of justice that connected them one to the other could change the social meaning of sustainability, allowing it to answer the “cry and demand” for a just distribution of both economic and environmental goods and services. We offer that sustainable justice (EJ2) has the potential of becoming this connective tissue. We conclude with an appreciation of the frame “just sustainability” which in some ways overlaps with sustainable justice, but find important differences.

A Typology of Justice

Since the mid-20th century, social movement justice demands have increasingly been modified in some manner—we’ve seen the rise of issue-specific justices such as housing, food, transit/transportation, education, workplace, and community justice. These justice frames are, of course, in addition to the broader frames of economic/environmental justice that we are focused upon, and the broadest of all: social justice. There are, undoubtedly, a number of reasons for this rise of modified justice claims (and we suggest it is an important area for study). One might surely be that they are responses to the vilification of any systemic critique/collective action, a vilification that is an essential component of neoliberalism, exemplified by the motto TINA (“There Is No Alternative” to corporate capital) espoused by the late Margaret Thatcher. Identifying specific injustices sidesteps an overt ideological challenge to the dominant social order while still issuing a call for a different distribution of, at least, certain goods and services. Another may be that the broadest of the justice frames—social justice—has no inherent resolution in its social meaning, thus pushing social movement organizers to a greater specificity in their demands. Certainly, there are good uses of a frame with this lack of specificity; it permits discussion and interaction that might otherwise be curtailed over differences in implementation; but its social meaning is vague without context and particular claims.

One-issue justice frames are important in that they provide a sense of urgency and immediacy to the identified injustice and can imply some form of redistribution of the goods themselves, e.g., a housing justice demand may be a campaign for building affordable housing, providing homeless shelters or ending bank redlining. Social justice is important in that it identifies injustice as being a broad social problem even if we do not know from which part of the social order the problem stems. However, we argue that neither the more specific one-issue justices, nor the broad frame of social justice, are well suited if we wish to explore the potential of sustainability itself as a frame that animates social action, particularly in urban settings.

Instead, we lift up and offer for discussion sustainable justice (EJ2 ), contending that this synthesis ties justice demands for redistribution of economic/environmental goods and services to sustainability itself. It does this through the history and meaning each part brings to the new whole. The economic justice frame calls up the heritage of conflicts over a skewed distribution of society’s material goods, bringing to present-day campaigns the DNA of struggles against exploitation, deprivation and the injuries of class. We can see in the Boyle Heights organizers’ demand for affordable housing the legacy of rent strikes and eviction defenses, the fight for public housing and—more recently—protests and refusals to leave foreclosed homes lost to predatory and subprime lending. The environmental justice frame brings the important dimension of “rights”—specifically rights that require the regulation and protection of the state (Harvey & Potter, 2009). The environmental justice frame raises issues of race and oppression along with those of health, pollution and land use, and—in the United States—ties them to the powerful civil rights movement of the mid-20th century. Combined, sustainable justice becomes a frame wherein: a) material (wealth) allocation becomes aligned with rights; and, b) the regulatory role of the state is expanded to include the redistribution of wealth. (On economic justice and housing, see Heskin, 1983, Burghardt, 1972, Tilly, 2006. On environmental justice, see Bullard, 1994, Taylor, 2000, and Capek, 1993).

The Social Meaning of Sustainability and Justice

Sustainability is, in some ways, conceptually similar to social justice: it has become ubiquitous in usage, but this very ubiquity leaves its social meaning ambiguous. As planning educator Scott Campbell put it in his seminal piece on cities and sustainability:

After all, if both the World Bank and radical ecologists now believe in sustainability, the concept can have no teeth… Actions speak louder than words and though all endorse sustainability few will actually practice it. Furthermore, any concept fully endorsed by all parties must surely be bypassing the heart of the conflict (Campbell, 1996, 301).

This “bypassing the heart of the conflict” is evident in any number of areas. Sustainability is the catchword of the day in realms ranging from the thoughtful to the pernicious. At the thoughtful end, we would note some of the sustainability conversation in planning where it may be a serious effort to reduce urban ecological footprints (Groc, 2007) and calls for balance in our relationship to nature. Towards the pernicious end, we would place planning initiatives that greenwash “business as usual” development (Gunder, 2006), along with savvy marketing strategies promulgated to convince us to become more sustainable by consuming more products (McKibben, 2011).

Indeed, as Campbell points out later in the article quoted above: “In the battle of big ideas, sustainability has won” (Campbell, 1996, 301). But what has been won? Calling up the conflict over housing in the freeway buffer, we note that land-use policies permitting affordable housing in the buffer and land-use policies banning it could each be promulgated under a sustainability-planning regime without any consideration of justice. Transit-oriented development is touted as sustainable development by many a planning agency but there is a growing body of research showing it often results in gentrification and displacement—and that displacement can negate the touted environmental benefits (Chapple, 2010, Domenie, 2012, Memo communication, Karner & Niemeier, May 24, 2012). Alas, on its own, the present ambiguity of sustainability renders it impractical as an organizing frame that could address the conflict between two injustices.

This impracticality of sustainability as an animating frame for social movement activists was borne out in a 2009 study of community development activists in the greater Los Angeles area. Seventeen organizations (14 economic justice groups and three environmental justice groups) were interviewed and queried regarding their organizing frames. Although 15 of the 17 were combining environmental and economic justice frames, at that point none utilized the term sustainability in their organizing. The reasons all related to the ambiguity of the concept—it does not easily translate into other languages and is without an inherent implementation (Breidenbach, 2010).

Sustainability becomes more concrete and potentially applicable to the “heart of the conflict” when we lift up its important rhetorical rubric—the three E’s: “environment” “economy”, and “equity.” As a slogan, the three E’s are watchwords highlighting the core conflicts that sustainability needs to resolve between the natural world, the political economy and the social order. This is a definitive step forward, but the ambiguity of sustainability remains unless we find a connective tissue among the three E’s that implies implementation. Not surprisingly, we suggest a helpful tool is at hand: sustainable justice. With sustainable justice weaving together the three E’s, the history of social movements and struggles embodied in its meaning have the potential of transforming sustainability from a concept with “no teeth” into one that can animate action. The importance of a change along these lines was evident in the prescient comment from economist Alain Lipietz when he argued that we know people fight for the principle of justice, but to date we do not see those who “mobilize, struggle or die for the principle of ‘sustainability’” (Lipietz, 2000, 83, emphasis added).

Our construct of sustainable justice should not be interpreted as a call for yet another “justice”, nor—even if a new one is necessary—that it should come from anywhere but actual social movements. Nor are we suggesting that infusing sustainability with the concept of justice would, perforce, resolve the on-the-ground conflict of what land-use policy should be implemented in Boyle Heights (housing in the buffer or not). It would, however, lift up and acknowledge the fact that there are situations where these contradictions exist and must be resolved through a systemic analysis and long-term change.

Sustainable Justice <-> Just Sustainability

Ours is not the first foray into grafting sustainability to justice. One of the most interesting we have seen is the concept of “just sustainability”, proposed by environmental educator Julian Agyeman, with sociologist and environmental justice scholar Robert Bullard and planner Bob Evans (Agyeman, et al, 2003, Agyeman, 2005). These authors have argued forcefully that if sustainability is ever to be truly transformative “…justice and equity issues need to be incorporated into its very core…[and] require [it] to take on a redistributive function” (Agyeman, 6). On this point we completely agree, without a redistribution of society’s material goods and services, without a redistribution of the environmental goods and bads that stem from our present production and distribution system, there is no way to achieve a social order that does not destroy both nature and humans.[vi] The frames sustainable justice and just sustainability overlap but there are differences in emphasis that apply in different circumstances. Just sustainability comes out of the authors’ “concern to understand ‘environmental justice’…[their] principal focus…is upon questions of equity and equality, as opposed to social justice” (324).

Our interest, however, is in how calls for justice that animate social movement organizing—specifically in urban settings—can be incorporated into the social meaning of sustainability.

If sustainability is the act and just the modifier, we are still without an inherent implementation process. As we’ve pointed out, sustainability is—at present—simply too ambiguous to include within itself any performative meaning. Instead, our analysis leads us to suggest that, as Harvey and Potter claim in the opening epigraph, the history of positive social change is motivated by a desire for justice—a desire to rearrange the social order and redistribute its goods and services. Yoking sustainability to this history expands its social meaning and potential as an organizing frame. Just sustainability is an appropriate analytic lens through which to examine policy and planning, but we believe that sustainable justice is what will animate social movements for permanent, systemic change.

Interviews

Our thanks to the interviewees who agreed to talk to us and provide us information in spite of busy and demanding schedules.

Community Groups

Maria Cabildo, Executive Director, ELACC

Ami Pascual, Associate Director, ELACC

Mike Dennis, Director of Organizing, ELACC

Jorge Villanueva, Community Organizer, ELACC

Reina/Rey Fukada, Community Organizer, ELACC

Leonardo Vilchis, Executive Director, Union de Vecinos

Public Agencies

Ken Bernstein, Senior Planner, Los Angeles City Planning Department

Diego Cardoso, Los Angeles City Planning Commission; Executive Director, Transportation & Development, LA Metro

Connie Chung, Senior Planner, Los Angeles County Regional Planning Department

Lois Starr, Former Director, Housing Production, Los Angeles County Community Development Commission

Linda Wheaton, Director, Intergovernmental Affairs, CA State Department of Housing & Community Development

Academic and Foundation

Douglas Houston, PhD, Associate Professor, University of CA, Irvine

Manuel Pastor, PhD, Director Program for Environmental & Regional Equity, University of

Southern California

Michele Pritchard, Director of Special Projects, Liberty Hill Foundation

References

ACT-LA (Alliance for Community Transit-LA) (2013). Available at: www.allianceforcommunitytransit/org/about-us.

Agyeman, J. (2005). Sustainable Communities and the Challenge of Environmental Justice. New York, NY: New York University Press.

Agyeman, J., Bullard, R.D., Evans, B. (2003). Just Sustainabilities: Development in an Unequal World. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Blee, K.M. & Taylor, V. (2002). Semi-structured Interviewing in Social Movement Research. In B. Klandersman & S. Staggenborg (Eds). Methods of Social Movement Research. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Boyle Heights Beat (17 August 2012). With Money Tight More Families Share Housing. Retrieved 15 December 2012 from http://www.boyleheightsbeat.com/with-money-tight-more-families-share-housing-117.

Boyle Heights Community Plan (BHCP) (1998). Available at: LA City Planning Department (LA DCP) http://cityplanning.lacity.org/complan/pdf/bhtcptxt.pdf

Breed Street Shul Project (n.d.). Available at: http://breedstreetshul.org

Breidenbach, J. (2010). Wrestling with Sustainability: Growth, Land Use Development and the Struggle for Justice in Los Angeles. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Prescott College: Prescott, AZ.

Bullard, R.D. (Ed.) (1994). Unequal Protection: Environmental Justice and Communities of Color, San Francisco, CA: Sierra Club Books.

Burghardt, S. (1972). Tenants and the Urban Housing Crisis. Dexter, MI: The New Press.

California Air Resources Board (CARB) (2003). Community Air Quality Monitoring: Special Studies, Boyle Heights, Los Angeles County.

California Environmental Protection Agency (Cal-EPA) & California Air Resources Board (CARB) (2005). Air Quality and Land Use Handbook: A Community Health Perspective.

California Environmental Protection Agency (Cal-EPA) & California Air Resources Board (CARB) (2012). Status of Research on Potential Mitigation Concepts to Reduce Exposure to Nearby Traffic Pollution.

Campbell, S. (1996). Green Cities, Growing Cities, Just Cities? [Electronic version]. Journal of the American Planning Association, 62(3), 304-312.

Capek, S. (1993). The “Environmental Justice” Frame: A Conceptual Discussion and an Application. Social Problems, 40(1). 5 – 24.

Chapple, K. (2009). Mapping Susceptibility to Gentrification: The Early Warning Toolkit. Berkeley, CA: Center for Community Innovation, University of California, Berkeley.

Chung, C. (2012). Freeway Traffic Impacts: Los Angeles County [Powerpoint slides].

City-Data. Available at http://www.city-data.com/neighborhood/Boyle-Heights-Los-Angeles-CA.htm

Clean Up, Green Up (2012). Available at http://cleanupgreenup.wordpress.com/

Cortright, J. (2009). Walking the Walk: How Walkability Raises Home Values in U.S. Cities. N.p.: CEO’s for Cities.

De Leon-Menjivar, C (23 June 2011). Buffer Possible for TI Freeway, Gazettes. Retrieved December 18, 2012 from http://www.gazettes.com/news/buffer-possible-for-ti-freeway/article_7e5d5aea-9de6-11eO-b7e3-001cc4c002e0.html?mode=print.

Dominie, W. (2012). Is Just Growth Smarter Growth? The Effects of Gentrification on Transit Ridership and Driving in Los Angeles’ Transit Station Area Neighborhoods. Unpublished Master’s Thesis, University of California, Los Angeles.

East Los Angeles Community Corporation (ELACC) www.elacc.org.

East Los Angeles Community Corporation (ELACC) (2010). Plan del Pueblo [Electronic Version]. ELACC: Los Angeles, CA

Estrada, David (2008). The Los Angeles Plaza: Sacred and Contested Space. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

Foley, G. (1999). Learning in Social Action: A Contribution to Understanding Informal Education. New York: Zed Books.

Fulton, W. & Shigley, P (2005). The Basic Tools. Guide to California Planning, Point Arena, CA: Solano Press Books.

Gauderman, W. J. , et al (2007). Effect of Exposure to Traffic on Lung Development from 10 to 18 Years of Age: A Cohort Study [Electronic version]. The Lancet, Vol. 369, 571-577.

Groc, I. (2007). Keep Your Footprint Out of My Backyard [Electronic version]. Planning, 73(1), 32-37.

Haas, P. et al (2010). Transit-Oriented Development and the Potential for VMT-related Greenhouse Gas Emissions Growth Reduction. Chicago, IL: Center for Neighborhood Technology (CNT).

Hall, S. (1996). Gramsci’s Relevance for the Study of Race and Ethnicity. In D. Moreley & K-H Chen (Eds.). Stuart Hall: Critical Dialogues in Cultural Studies. London: Routledge.

Harvey, D. & Potter, C. (2009). The Right to the Just City. In Marcuse, P. et al, (Eds). Searching for the Just City: Debates in Urban Theory and Practice. New York: Routledge

Heskin, A.D. (1983). Tenants and the American Dream: Ideology and the Tenant Movement. New York: Praeger.

Hirt, S. (2007). The Devil Is in the Definitions: Contrasting American and German Approaches to Zoning [Electronic Version], Journal of American Planning Association, 73(4), 436-450.

Horton, M. & Freire, P. (1990). We Make the Road by Walking: Conversations on Education and Social Change. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

Houston, D. (2012). Overview of Strategies to Reduce Exposure to Near-roadway Air Pollution [Powerpoint slides].

Hu, S., et al. (2012). Observation of Elevated Air Pollutant Concentrations in a Residential Neighborhood of Los Angeles Using a Mobile Platform [Electronic version], Atmospheric Environment, Vol. 51, 311-319.

Japanese American National Museum (JANM) (2005). Los Angeles’ Boyle Heights. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing.

Kennedy, M. & Leonard, P. (2001). Dealing with Neighborhood Change: A Primer on Gentrification and Policy Choices. Washington DC: Brookings Institution Center on Urban & Metropolitan Policy.

Krueger, R. & Gibbs, D. (2007). The Sustainable Development Paradox: Urban Political Economies in the United States and Europe. New York: The Guildford Press.

Lefebvre, H. (1996). Writings on Cities. E. Kofman, E. Lebas (Trans). Malden MA: Blackwell Publishers.

Lipietz, A. (2000). Political Ecology and the Future of Marxism [Electronic version]. Capitalism, Nature, Socialism, 11(1) 69-85

Los Angeles City Department of City Planning (LA DCP) (2008). City of Los Angeles Local Population and Housing Profile, Boyle Heights Community Plan Area, retrieved October 10, 2011 at http://cityplanning.lacity.org.

Los Angeles City Housing Department (LAHD) (n.d.) LAHD Rent Stabilization Ordinance Information. Available at http://lahd.lacity.org/lahdinternet/RentStabilization/tabid/247/language/en-US/Default.aspx

Los Angeles Collaborative for Environmental Health and Justice (2010). Hidden Hazards: A Call to Action for Healthy, Livable Communities. Los Angeles CA: Liberty Hill Foundation.

Martin, D.G. (2003). “Place-Framing” as Place-Making: Constituting a Neighborhood for Organizing and Activism” [Electronic version]. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 93(3), 730-750.

McKibben, B. (2010). Eaarth: Making a Life on a Tough New Planet. New York: Times Books, Henry Holt and Company

Moore, J. (1991). Going Down to the Barrio: Homeboys and Homegirls in Change. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

Nelson, A.C. (2011). The New California Dream: How Demographic and Economic Trends May Shape the Housing Market; A Land Use Scenario for 2020 and 2035. Los Angeles: Urban Land Institute.

NLIHC (National Low-Income Housing Coalition) (2012) Advocates’ Guide to Housing & Community Development Policy. Available at: http://nlihc.org/sites/default/files/2012-Advocates-Guide_o.pdf

Oliver, P.E. & Johnston, J. (2000). What a Good Idea? Ideologies and Frames in Social Movement Research [Electronic version]. Mobilization: An International Journal, 4(1), 37-54.

Parr, A. (2009). Hijacking Sustainability. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Parsons, D. (2005). Making a Better Word: Public Housing, the Red Scare and the Direction of Modern Los Angeles, Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press

Perez, L. Lurmann, F. et al (2012). Near-Roadway Pollution and Childhood Asthma: Implications for Developing “Win-Win” Compact Urban Development and Clean Vehicle Strategies [Electronic version]. Environmental Health Perspectives. 120 (11), 1619-1626.

Pollack, S., et al (2010). Maintaining Diversity in America’s Transit-Rich Neighborhoods: Tools for Equitable Neighborhood Change. Boston, MA: Dukakis Center for Urban and Regional Policy.

SB 352. Schoolsites: Sources of Pollution. Senator M. Escutia. Amends Section 17213 of the Education Code and Section 21151.8 of the Public Resources Code. Sacramento, CA.

Schwartz, A. (2010). Housing Policy in the United States, 2nd Ed. New York, NY: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

Serviss, J. (30 March 2011). Public Housing Residents of Boyle Heights Face an Uncertain Future. Transcript from KPCC-FM broadcast. Retrieved January 21, 2013 from http://www.scpr.org/news/201/03/20/25457/public-housing-residents-boyle-heights-face=uncert/.

Snow, D.A. & Benford, R. d. (1992). Master Frames and Cycles of Protest. In Frontiers in Social Movement Theory, Morris, A.D. & Mueller, C. M. (Eds). New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Snow, D.A. & Trom, D. (2002). The Case Study and the Study of Social Movements. In B. Klandermans & S. Staggenbord (Eds). Methods of Social Movement Research. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

South Coast Air Quality Management District (SCAQMD) (2005). Guidance Document for Addressing Air Quality Issues in General Plans and Local Planning.

Speth, J.G. (2008). The Bridge at the End of the World: Capitalism, the Environment, and Crossing from Crisis to Sustainability. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Taylor, D.E. (2000). The Rise of the Environmental Justice Paradigm [Electronic version]. American Behavioral Scientist, 43(4), 508-580.

Tilly, C. (2006). The Economic Environment of Housing: Income Inequality and Insecurity. In A Right to Housing: Foundation for a New Social Agenda, Bratt, R., M. E. Stone & C. Hartman (Eds). Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

Urban Land Institute (ULI) (2010). Land Use and Driving: the Role Compact Development Can Play in Reducing Greenhouse Gas Emissions. Washington DC: Urban Land Institute.

Wallace, S. (2011). From the Ground up to the Sky: Bringing Aging and Child Advocates Together to Expand Traditional Air Quality Coalitions. [Powerpoint slides].

Wallace, S. (n.d.). Equipping Communities to Fight for Clean Air: ARRA Success Story. Retrieved from: http://www.niehs.nih.gov/research/supported/recovery/success/wallace/index.cfm.

Westby, D.L. (2002). Strategic Imperative, Ideology and Frame [Electronic version]. Mobilization: An International Journal, 7(3), 287-304

Yee, T. (2012). Alliance for Community Transit (ACT-LA). [Powerpoint slides].

[i] By 1920, there were over 75,000 Jewish immigrants in Boyle Heights. This population and the synagogue they built were each the largest west of Chicago (Breed Street Shul Project, 2012).

[ii] “Affordable housing” is a normative concept, identifying permanent shelter that is income-restricted through some form of public policy intervention. The intervention may be in the form of subsidies provided directly to residents or embedded in the construction of the buildings themselves. Households live in “affordable” housing when paying no more than 30% of gross monthly income for shelter. Eligibility is generally determined by household income relative to area median income (AMI). “Low-income” is less than 80% of AMI, “very-low-income” is less than 50% AMI and “extremely low-income is less than 30% AMI (NLIHC, 2012).

[iii] Often confused, gentrification and displacement are not the same process. Gentrification refers to in-migration of higher-income households into formerly low-income neighborhoods, often precipitating higher rents/prices, along with changes in commercial businesses that increase costs for the original residents. Displacement occurs when these changes force low-income people to leave, either through unaffordable rent increases or evictions. Gentrification does not necessarily result in displacement (Kennedy & Leonard, 2001, Dominie, 2012).

[iv]While LACDC staff was concerned about health and environmental justice, the BOS actually made their decision based on cost factors. In California, counties provide health-of-last-resort for the indigent poor. The BOS determined that they would not fund even mitigated subsidized housing in the buffer to prevent having to provide medical services to those made sick from the pollution. They had no comparative data on the County’s health costs for low-income children made sick from unhealthy and slum housing outside the buffer (Starr, personal communication, 21 January 2013).

[v] Community Plans are geographically specific “subsets” of General Plans; they outline a long-term development vision for identified neighborhoods, specifying zoning, land uses and even particular development sites (Fulton & Shigley, 2005). While not legally required, large cities such as Los Angeles, New York, etc., utilize them extensively. Long ignored as dusty planning exercises, activists engaged in “redistributing development” are finding them useful organizing tools.

[vi] On sustainability as resolution of the contradictions of capital, see Speth, 2008, on the contradictions of sustainability in urban development, see Krueger & Gibbs, 2007, on the potential of a politics of sustainability, see Parr, 2009.

Photos: 1. Jan Breidenbach; 2. Jesus Herrera; 3. Article ID picture

Jan Breidenbach teaches housing, urban and community development at the USC Price School of Public Policy. Prior to joining USC, she had a 30-year career as a community and union organizer, and leading advocate for affordable housing. She received her MA in Urban Planning from UCLA and her PhD in Sustainability Education from Prescott College. She is a Senior Fellow at the UCLA School of Public Affairs and a contributing editor to Shelterforce, a journal of housing and community development. In addition to teaching, she consults with community organizations on strategic campaigns. She can be reached at breidenb@usc.edu.

Jan Breidenbach teaches housing, urban and community development at the USC Price School of Public Policy. Prior to joining USC, she had a 30-year career as a community and union organizer, and leading advocate for affordable housing. She received her MA in Urban Planning from UCLA and her PhD in Sustainability Education from Prescott College. She is a Senior Fellow at the UCLA School of Public Affairs and a contributing editor to Shelterforce, a journal of housing and community development. In addition to teaching, she consults with community organizations on strategic campaigns. She can be reached at breidenb@usc.edu.  Jesus Herrera is a Master’s Candidate in Urban Planning at the USC Price School of Public Policy, with a concentration in transportation planning. Born and raised in Los Angeles, he has experienced and seen some of the adverse effects that result from economic/environmental injustice in L.A.’s various communities. He can be reached at herrera1@usc.edu.

Jesus Herrera is a Master’s Candidate in Urban Planning at the USC Price School of Public Policy, with a concentration in transportation planning. Born and raised in Los Angeles, he has experienced and seen some of the adverse effects that result from economic/environmental injustice in L.A.’s various communities. He can be reached at herrera1@usc.edu.