In search of “We the People” in Light of Plato’s “Allegory of the Cave”

Lepp Friesen JSE General Fall 2019 Issue PDF

Link to the JSE General Issue Fall 2019 TOC

Abstract: In this article, I view Alvarez Armando’s “We the People” sculpture in Gallup, New Mexico, through the lens of Plato’s “Allegory of the Cave” and argue that although the message of the “We the People” art installation is to illustrate democracy and freedom, its staticity may contradict its intent and adds an additional layer to its interpretation. The “We the People” art sculpture invites interaction, but interaction, like in Plato’s “Allegory of the Cave,” is limited in scope and perception. My exploration comes with questions about the meaning of cave dwelling and enlightenment. What is the meaning of “We the People” when equality is not something every citizen can take for granted? Are we then an enlightened society that think we have gained exit from cave dwelling when freedom and a particular interpretation of democracy is not designed for everyone?

Keywords: “Allegory of the Cave, democracy, “We the People”

In Gallup, New Mexico, the “We the People Park,” derives its name from an interactive steel sculpture installed in 1994, created by sculptor Alvarez Armando. A semi-circle 8-foot steel wall spanning 310 feet, captures 113 silhouette cut-outs in mid activity. Children are running and playing basketball; men are playing guitar and singing enthusiastically; women are dancing and holding their children’s hands. If the characters could separate themselves from the steel wall, they would walk in society like stiff monochrome flat characters, but they cannot because they are securely attached to the wall with thick steel staples. Behind the wall are boulders, plants, pebbled walkways, 16 empty chairs, and steel figures standing at lecterns. According to Armando, the sculpture commemorates “free speech, pluralism, democracy, and our coexistence with the environment” (We the People, 2019).

I used to live in Gallup, New Mexico, and we used to take our children to the “We the People” park, where they would sit in the chairs and run the paths in a game of tag. At the time, I was fully aware that Gallup was surrounded by the Navajo Nation, but my knowledge of the history of the land I was living on was somewhat limited. I taught Freshman Composition part-time at the University of New Mexico, and most of my students were Native American. It isn’t until now, almost 20 years later, with prompting from people and readings along the way, that I have figuratively gone back to the “We the People” park and thought about its meaning and intent.

But first, let me introduce myself. Hello. Guten Tag. Hola. My name is Helen Lepp Friesen and I am the descendant of settlers Peter and Helen Lepp. My father, Peter, came to Canada from Ukraine, as a refugee, in 1918. My mother, Helen, was born in Saskatchewan. Her parents came to Canada as refugees as well. Both of their families were originally from Holland, but had made their way across Europe attempting to escape religious persecution. In Canada, they purchased land from the government on the traditional territory of the Ojibway, Cree, Dakota Plains, Sioux, and there they farmed all of their life.

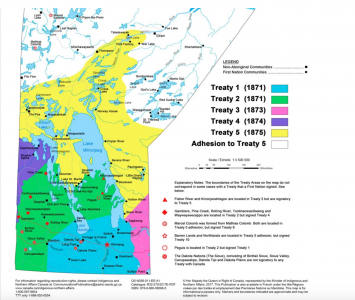

(First Nations and Treaty Areas in Manitoba, 2010.) With the inclusion of this map, I acknowledge the limitation and problem of mapping from a colonial perspective.

In the late 60s and early 70s, as I caught the yellow school bus that lumbered down the gravel roads to my rural school, I had no knowledge of the residential schools that operated in my country, and no knowledge of children that were being taken away from their parents in the 60s Scoop, including right out of Indigenous reserves near my rural farming community. In university, I studied Western Civilization, with still no knowledge about the territory I was on. It wasn’t until much later that I learned about residential schools, the 60s Scoop, and murdered and missing Indigenous women and girls. I continue to learn about the history of what has gone on in this land long before I arrived here with a backpack of privilege and erroneous entitlement. I did not know that my family and I benefitted from a violent past and a current legal constitution that still disenfranchises not only Indigenous Peoples, but other marginalized groups.

I now live in Winnipeg on the traditional territory of the Anishinaabeg, Cree, Oji-Cree, Dakota, and Dene Peoples, and the Métis homeland. The University of Winnipeg, where I teach, is located in the heart of downtown. Of the 10,000 students, 13% self-identify as Indigenous. When I have taught in a ground floor classroom with windows right next to the sidewalk, sometimes passersby cup their hands to the window and peer in. We work where everyday life happens all around us and in our classrooms, and sometimes I wonder who is looking in on whom. It reminds me of Plato’s (1985) “Allegory of the Cave.” In our glass- encased classroom, I wonder whether we are in Plato’s cave or is it the people walking by on the sidewalk?

In this article, I view the public “We the People” sculpture through the lens of Plato’s “Allegory of the Cave” and argue that although the message of the “We the People” art installation is to illustrate democracy and freedom, its staticity may contradict its intent. Although viewers may think the “We the People” sculpture depicts democracy and free speech, it may be illustrating precisely the opposite and perhaps that is its intent.

The “Allegory of the Cave” is an excerpt from Book 7 in philosopher Plato’s The Republic, featuring a dialogue between Plato’s mentor Socrates and his brother Glaucon. Plato says that “allegory may show us best how education – or lack of it – affects our nature” (Plato, 1985). Socrates describes a scene where cave dwellers are shackled in a cave in such a way that they can only see what is ahead of them. Behind them, a fire is burning. In between the imprisoned cave dwellers and the light, puppeteers move objects behind a low wall that cast shadows on the cave wall in front of the prisoners. Since the prisoners are only able to see shadows, they think that the shadows are real and the only subject of conversation that the prisoners can engage in is on the topic of shadows. A prisoner is set free from his shackles and can now look around to see the fire and the shadows. He tries to make sense of this new reality as he realizes the fire is three dimensional, and the shadows are fuzzy replicas of the images on the wall. Next, the prisoner makes his way out of the cave, where he sees the sun for the first time. At first, the brightness dazzles him, but once his eyes adjust, he can see nature and color. He realizes that the statues were just replicas of what he sees in reality. Excited, he returns to the cave to announce his realizations to the other shackled prisoners. When the enlightened cave dweller returns to tell his friends still in the cave, they don’t believe him and eventually kill him for his heretic ideas (Plato, 1985).

What does Plato’s “Allegory of the Cave” have to do with Armando’s “We the People” art installation and what does this all have to do with current university learning? Plato (1985) asks whether art is faulty or deficient and whether art requires another skill to interpret art? (Plato, book 1 part 3 The Republic). Armando created an art installation that is indeed pure and with its many pieces and thought that went into it, has accomplished his goal in illustrating democracy, leaving it up to the viewer to find the deficiency and faults of freedom and free speech.

The “We the People” art sculpture invites interaction, but interaction, like in Plato’s “Allegory of the Cave,” is limited in scope and perception. The life-size steel cut-outs in the sculpture could be likened to the chained prisoners in the cave because, like the prisoners in the cave, the cut-outs also are shackled in place. I argue that like the static cut-outs, the concept of ‘we the people’ in the art installation, although as art represent democracy and freedom, in reality also represent the limitation of ‘we the people’ in society. I struggle with the questions of inclusion and exclusion of ‘we the people’ in society. Do our communities embrace a ‘we the people’ ideology, or are there steel cut-outs stapled to walls that will never emerge from their shackles because social norms have stapled them there? Who is included in ‘we the people,’ and who is excluded?

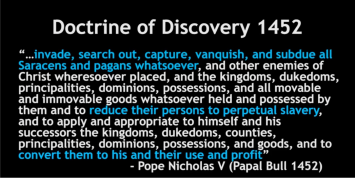

Mark Charles (2019) who hails from New Mexico, the home of the “We the People” sculpture, claims that in the United States, ‘we the people’ never meant all the people. In his 2019 TED Talk in Tyson, Virginia, he talks about how “’We the People’ are the three most misunderstood words in U.S. history” (Charles, 2019). Charles (2019) outlines how the history of the country is based on a philosophy of subordination of some people to benefit others. To illustrate his point, he cites from the Doctrine of Discovery. In 1452 in the Doctrine of Discovery Pope Nicholas V wrote:

The Doctrine of Discovery was an official document issued by European monarchies that legitimatized colonization. Based on religious and political reasons, the document justified European settlers’ seizure of land from Indigenous peoples. The Doctrine of Discovery ideology led to not only the domination of land in North America, Africa, New Zealand, Australia, and Asia, but also “supported the dehumanization of those living on the land and their dispossession, murder, and forced assimilation” (Doctrine of Discovery, 1452, Upstander Project). This same doctrine led to Columbus’ claim to “discover America.” Charles (2019) asserts that the Doctrine of Discovery is a white supremacist document that assumes the dehumanizing of Indigenous Peoples.

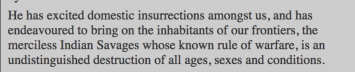

Charles (2019) points out that even in the Declaration of Independence a few lines after the statement that all men are created equal, the document talks about Indigenous people as savages.

Charles (2019) asserts that “we would rather believe that the United States of America is racist and sexist and white supremacist in spite of our foundations but the truth is that we are white supremacist, racist and sexist as a nation because of our foundations and we don’t know what to do with that” (Charles, 2019 TED Talks). Charles (2019) goes on to say that African Americans and women will not be included as equals until we deal with the racism and sexism woven into the fabric of our doctrine. He states that until we have acknowledged the flaws in our foundation and made changes, we cannot be ‘we the people’ (Charles, 2019). “Native Americans, my people, will never be included in ‘we the people’ until as a nation, we deal with the doctrine of discovery and our dehumanizing precedence for land titles” (Charles, 2019). Background and ethnicity determine experience and memory in North America. People of color carry a memory of segregation and mass incarceration; Indigenous peoples carry a collective memory of residential schools and separation from families; people of settler descent do not share those memories and often do not even know about these tragic events. Charles (2019) challenges us to create a shared memory and the need for a national dialogue about race, gender, and class. “We need to leave a different legacy” (Charles, 2019).

How do we go about leaving a different legacy? Sometimes it seems like our work is like placing Band-Aids on a festering issue much larger than what appears on the surface. In his State of the Union address on January 13, 2016, then President Barak Obama said, “’We the People.’ Our Constitution begins with those three simple words, words we’ve come to recognize mean all the people, not just some; words that insist we rise and fall together, and that’s how we might perfect our Union. And that brings me to the fourth, and maybe the most important thing that I want to say tonight. The future we want — all of us want — opportunity and security for our families, a rising standard of living, a sustainable, peaceful planet for our kids — all that is within our reach. But it will only happen if we work together. It will only happen if we can have rational, constructive debates. It will only happen if we fix our politics” (Obama, 2016).

Can our politics be fixed if the lack of inclusion is woven into the very nature of our politics? Armando creates an exceptionally vibrant piece of art to illustrate a powerful concept of democracy, free speech, and pluralism; at the same time, he inspires and invites interaction and conversation. Looking at Armando’s 1994 sculpture in light of Charles’ current assertion 25 years later, that racism and sexism are ingrained into the fabric of the American constitution, inserts a poignant layer to the interpretation of Armando’s sculpture. Although the silhouettes illustrate life, relationships, familial ties, everyday activities like singing and music, they are still stationary, immobile, and will forever remain attached to the wall without ever having the ability or opportunity to step from their inert place in their steel artistic world. The silhouettes stapled to the steel wall in Armando’s sculpture are reminiscent of Plato’s allegory of the cave where people chained in a dark cave think that the shadows flashing by on a wall are the essence of reality.

We immediately presume we are enlightened by our knowledge and freed from dark cave-dwelling, but Plato claims we all wander in darkness blinded by myths we learn to believe from our place in society. Plato himself came from a privileged background during his own time in 400s B.C.. He had time to think and write about philosophy, when other people in his Greek society were slaving away at menial jobs rendering his philosopher king ideology contradictory to his “Allegory of the Cave.” Is democracy and free speech mere “phantoms projected by our culture onto the walls of our fragile and flawed minds, but because everyone around us is insisting that they are genuine we are taken in at a young age” (The School of Life, 2016).

If we bluntly tell people that they are wrong, they will not take kindly to that style of confrontation, which is what happened to Plato’s teacher Socrates at that time, who was sentenced to death for his anti-democratic views (“The Suicide of Socrates, 399 BC”).

Plato’s pedagogical plan for education was not forceful, but based on a method of inquiry and curiosity. “It’s a gentle process. Wisdom starts with owning up to ignorance. You never teach anyone anything by making them feel stupid even if they are at first” (The School of Life, 2016).

Armando’s method of teaching through art is aligned with the Socratic method of inquiry. Quietly the “We the People” sculpture has been sitting north of I-40 not yelling at anyone. Not even saying anything, at least not loudly. Armando’s inert silhouettes could be seen as imagining they are experiencing democracy and free speech when in reality, we know that although what they represent carries a powerful message, knowledge or life cannot emanate from steel lips on one-dimensional cut-outs. A question then arises is are we like the silhouettes stapled to a steel wall imagining that we have free speech and that democracy works in our society. What is our response when an idea like Charles’ arises startling all of us to the realization that perhaps into the very heart of democracy, a flaw has been woven that we were never able to see before? We needed a liberated soul, someone that descended from the steel wall and gained experience in society to open our eyes to the limitations of our existence in what we thought was a free society.

Are we in the cave as we occupy space in a ground floor classroom busily writing what we think wise words as we ignore those outside walking by our windows, all the while pretending that we have accomplished the goal of enlightenment? I wonder about the people that wander by my ground floor classroom and cup their hands to peer into an institution that has caused a lot of damage. What form and shape would they take in Armando’s sculpture and who are they in Plato’s allegory? Have they gained sight and knowledge already or are they imagining shadows on the wall?

There have been many interpretations of the “Allegory of the Cave,” one including that education or enlightenment is freedom, is the process of unshackling and escaping from a place of darkness and illusions. Education opens eyes to see color and light. Listening to Mark Charles’ TED Talk brought me to the realization that although I have always thought I was educated, I also was shackled to illusions thinking that what I saw was reality. Taking a step back and thinking about what Charles said that racism and sexism is woven into the fabric of our constitutions and therefore our society, filled me with deep sadness. What is the meaning of “We the People” when we incarcerate millions of people, and mostly people of color, and when people still experience discrimination? Are we an enlightened society that think we have gained exit from cave dwelling? How will things ever change? Before I saw in part because I knew perceptions of race and class needed to change and I felt like I did my part by teaching courses like Human Rights in Education and Cross-Cultural Education.

In one of my Cross-Cultural Education classes in a class full of mostly white middle-class pre-service teachers, frustration erupted one day. One young man voiced his concern that he was tired of all classes addressing white privilege and hadn’t they learned enough about that. As a white middle-class teacher, I was stumped and didn’t know how to respond. I didn’t need to. One of the few Indigenous students in the class stood up, and with a calm voice talked to the class. Tension defused and dissolved palpably. Years later, I met that student at an event. Enthusiastically I went to speak with her and thank her for her brilliant contribution to the class. I asked her, “Do you remember that class when you stood up and talked to the students and you managed to calm the whole class down?” She shook her head. She did not remember and asked what she had said. I thought about it and said, “I don’t remember what you said. It was your attitude that spoke the message.”

I remember that now as I consider my new learning. Changing the constitution is not going to happen overnight, but if my attitude can speak a message, then I will hopefully have accomplished at least a small step in my journey out of the darkness of the cave. “Fixing our politics” as Obama (2016) said may be more difficult than we think. Fixing our politics will only happen if we fix our thinking. Fixing our thinking will only happen if we open our hearts to see and understand. Seeing and understanding is sometimes a fuzzy process of acclimating our eyes to a new light and horizon, like the fuzziness, questions, and meandering of this article exploring a journey of leaving the darkness of a cave.

Classroom resources:

Acknowledging the historical Indigenous territory is one way to recognize the history of colonialism. On the online site Native-Land.ca (https://native-land.ca), people can learn about the Indigenous groups that lived in any given area in North America. Native Land also includes a teachers’ guide to provide instructors with resources for how to use it in classrooms.

On Faculty Focus, Heather Van Mullem provides strategies for creating a social justice consciousness in the classroom. https://www.facultyfocus.com/articles/effective-classroom-management/teaching-about-power-and-privilege/

Sharing Power in the Classroom gives examples of conversation starters to discuss power dynamics in the classroom and methods for empowering students. https://utah.instructure.com/courses/148446/pages/sharing-power-in-the-classroom

Further reading and literature on privilege and power:

Ayyad, F. (2015). Higher Education and Privilege: 21st Century Issues. College Student Affairs Leadership, 2(2). Retrieved from http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/csal/vol2/iss2/2

Gross, M. (2018). Power in Plain Sight: Exploring the Class Privilege at in Curriculum at Wealthy High Schools (MA Thesis, University on San Francisco, California, USA). Retrieved from https://repository.usfca.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1961&context=capstone

Guerra, J. (2015, February 16). Fitting in on campus: Challenges for first-generation

students. nprEd. Retrieved from http://www.npr.org/blogs/ed/2015/02/16/385470288/fitting-in-on-campus- challenges-for-first-generation-students

King, T. (2012). The Inconvenient Indian: A curious Account of Native People in North America. Toronto: Random House Publishing.

Leiderman, S., Potapchuk, M., & Butler, S. (2009). Transforming white privilege, a 21st century leadership capacity. Center for Assessment and Policy Development. Retrieved from http://www.racialequitytools.org/module/overview/transforming- white-privilege

Luhby, T. (2012, June 21). Income inequality in America: Worsening wealth inequality by race. CNNMoney. Retrieved from http://money.cnn.com/2012/06/21/news/economy/wealth-gap-race/

McDermott, C. (2013, July 31). U.S. higher-education system perpetuates white privilege, report says. Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved from http://chronicle.com/article/US-Higher-Education-System/140631/

Mclntosh, P. (1981). White privilege and male privilege: A personal account of coming to see correspondences through work in women’s studies. College Art. Retrieved from https://www.collegeart.org/pdf/diversity/white-privilege-and-male-privilege.pdf

Miller, R. J., Ruru, J., Behrendt, L., & Lindberg, T. (2010). Discovering Indigenous Lands: The Doctrine of Discovery in the English Colonies. Oxford: University of Oxford Press.

National Center for Education Statistics. (2012). Degrees conferred by sex and race. Institute of Education of Sciences. Retrieved from

https://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=72

National Center for Education Statistics. (2014-2015). Tuition costs of colleges and

universities. Retrieved from http://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=76

Roach, R. (2013, July 24). Report: Steady college enrollment growth for

underrepresented minorities, college completion rates increasing more slowly. Diverse Issues in Higher Education. Retrieved from http://diverseeducation.com/article/54837/

Smith, L. T. (2012). Decolonizing Indigenous Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. London: Zed Books.

Quintana, C. (2019, February 15). Can This Man Change How Elite Colleges Treat Low-Income Students? Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved from https://www.chronicle.com/article/Can-This-Man-Change-How-Elite/245714?cid=cp270

Umbach, P. D., & Kuh, G. D. (2003). Student experiences with diversity at liberal arts

colleges: Another claim for distinctiveness. Paper presented at the 43rd Annual Forum for the Association for Institutional Research, Tampa, FL. Retrieved from http://www.nsse.indiana.edu/pdf/research_papers/experiences_with_diversity.pdf

Wilder, C. S. (2013, October 30). Shackles and ivy: The secret history of how slavery helped build America’s elite colleges (A. Goodman, Interviewer) [Video file]. Retrieved from http://www.democracynow.org/2013/10/30/shackles_and_ivy_the_secret_history

References

Charles, M. (2019). ‘We the People’ – the three most misunderstood words in US history. TEDxTysons. Retrieved on June 27, 2019 from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HOktqY5wY4A

Doctrine of Discovery. (1452). Upstander Project. Retrieved on June 27, 2019 from https://upstanderproject.org/firstlight/doctrine.

The Declaration of Independence. (1776). US history.org. Retrieved on June 27, 2019 from http://www.ushistory.org/declaration/document/

First Nations and Treaty Areas in Manitoba. (2010). Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada: Government of Canada. Retrieved on July 26, 2019 from https://www.aadnc-aandc.gc.ca/eng/1100100020576/1100100020578.

Obama, B. (January 13, 2016). State of the Union Address. The White House. Retrieved on June 27, 2019 from https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2016/01/12/remarks-president-barack-obama-–-prepared-delivery-state-union-address

Plato. (1985). The Republic. Translation of: Respublica. (R. W. Sterling & W. C. Scott, Trans). New York: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

The School of Life. (2016). Plato On the Allegory of the Cave. Retrieved on July 26, 2019, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SWlUKJIMge4.

“The Suicide of Socrates, 399 BC”. (2003). EyeWitness to History, Retrieved on July 26, 2019 from www.eyewitnesstohistory.com.

We the People. (2019). Smithsonian Art Inventory Sculptures on Waymarking.com. Retrieved on June 27, 2019 from http://www.waymarking.com/waymarks/WM96GG_We_the_People_Gallup_New_Mexico

Helen Lepp Friesen teaches in the Department of Rhetoric, Writing, and Communications at the University of Winnipeg. Her research interests are multimodal teaching of writing. She enjoys getting her students involved in practical writing activities such as performing writing on the university radio station and publishing a journal of student writing.

Helen Lepp Friesen teaches in the Department of Rhetoric, Writing, and Communications at the University of Winnipeg. Her research interests are multimodal teaching of writing. She enjoys getting her students involved in practical writing activities such as performing writing on the university radio station and publishing a journal of student writing.