Engaging Learners in Community Service Learning to Enhance Teacher Preparation Curriculum

Abstract: Project-based community service learning increases the effectiveness of sustainability education and demonstrates the importance of providing children with opportunities to be healthy, happy and eco-literate global citizens. At Wright State University, as students learned environmental and socio-economic content, they became informed citizens who were empowered as local change agents. Insights from these case studies illustrate how we can engage college students to foster skills as informed decision-makers and engaged future teachers. Examples of curricular models are proposed for educators and students to effectively address environmental dilemmas by integrating scientific content knowledge with civic engagement to best prepare sustainably literate citizens.

Key words: experiential learning, community service, project-based learning, teacher preparation

Expanding the Role of Community Service Learning

The imperative for informed, environmentally literate citizens grows daily. They will be our educated decision-makers as we face crucial long-term choices pertaining to environmental issues, sustainable choices and resulting behaviors. Tough questions need to be asked of policy makers and even more difficult decisions need to be made as to our global responsibilities (Hawkin 2007). How do we raise environmentally literate children and community members, who have a caring concern for the natural world? Can we move forward with educating children, through childhood play experiences, as to the intricate complexity of natural systems? How much of this thinking is first heard with the heart – how do we engender understanding and caring concern for the natural world? Effective change happens first on a local level where students, people can see and feel immediate impact of their efforts. Sobel (2005) makes the solid case that for children need to first understand their own backyard before trying to understand why we should protect the Rainforest. Like 4th graders sense of place extending their backyard to their school and neighborhood, where they can make a difference — high school and college students want to get involved. They want part of something larger than themselves by helping to make profound changes in their communities. They want to be members of communities that are healthy and functional.

It is through engagement and active involvement close to home that students learn that they have a voice and can have an appreciable impact. This is powerful. It is a fundamental human need to feel included, to feel a sense of belonging. McKibben (2007) makes the point that we humans have a deep-seated need to be part of a community. A sense of belonging to a community gives us a degree of happiness or at least contentment and security, if not comfort. Why else would fans continue to follow a sports team that loses season after losing season? It is that sense of being united in a common cause, having common unity — community.

Environmental education has benefited from adoption of a hands-on constructivist approach and John Dewey’s philosophy from 1897, that we learn by doing. Effective environmental programs present project-based classroom approach linked with out-of-school Community Service Learning. Arming our future citizens with these tools—knowledge, discernment, and empowering them to take action in solving problems—best equips them with life-long learning skills. Furco and Root (2012) state that 600 recent studies indicate that Community Service Learning provides a vehicle for setting standards for student engagement and including statistics to support its effectiveness. He cites that service learning and civic engagement is on the rise at colleges and universities, having grown in its use from 22%-69% since 1999 (Furco and Root 2012). Aligned with this message, McKibben (2007) makes the case for developing strong communities with citizens embracing community engagement and civic duty to solve problems on a local level. Engaging students in local community service projects in their school or neighborhood, empowers them as problem-solvers rather than overwhelming them with daunting environmental challenges.

When hearing short-sighted discussions about natural resources, transportation, energy and the human interface with the Earth, I often recall the scene in the 1988 movie, “Stand and Deliver” when Mr. Escalante repeatedly tells his students to think beyond the immediate problem, saying that he’s not worried them failing the AP test, he’s worried about them failing life. Like Mr. Escalante, dedicated teachers worry less about how their students will do on standardized testing but worry instead about preparing their students to do well in life.

Good teachers also take pride and ownership of their classroom. Many of the best teachers I met also have another characteristic that is true of their teaching. These same teachers have found ways to make content subject matter, matter. They make science, math, often viewed as the most difficult and “boring” subjects come to life for students by integrating this material into everyday life. They use some form of Project-based teaching methodology to engage their students and to make math/science, language arts, technology, social studies, etc., relevant and “real”. In his 2003 book, An Ethic of Excellence: Building a Culture of Craftsmanship in Schools, Ron Berger describes how he integrated this highly successful method into his 5th grade classroom. This slim but powerful book is a “must read” for all of my students because it provides a starting point for discussions of how to actively engage All learners in a project-based approach to education regardless of intellect or individual learning style.

At Wright State University our award winning Community Service Learning Program has been nationally recognized for the past four years in the President’s Higher Education Honor Roll with Distinction and recognition in fall of 2011 in The Washington Monthly Top 10 list of universities committed to community service. I have been fortunate to be involved in creating classes and developing curriculum for the Service Learning Certificate option that is similar to a minor. Below, I recount the evolution of two general education Service Learning courses followed by two examples of highly successful classes in our Early Childhood and Middle Childhood Teacher Preparation Program.

When we think of education or more specially, teacher education, we think of ensuring that students are prepared with classroom management skills and sufficient content knowledge. With the emphasis on improving K-12 students achievement on standardized test scores the growing trend is to hone in on meeting content standards and very specific lesson planning to meet those narrow goals. Yet the question remains – are we effectively preparing teachers to meet the needs of students in a rapidly changing world? When test scores are for the most part inadequate, particularly for the most venerable academically and socio-economically challenged students, are we truly preparing them for what the future holds? Is there a better way to prepare teacher candidates to more effectively teach today’s students and better prepare them for this fast-paced, ever-changing world? I’d like to address these questions and propose a solution.

Taking it to the Streets — Examples of Impactful Community Service Learning

For many years, using a project-based approach similar to Berger’s (2003), I’ve incorporated community service learning into all of my classes across a wide array of course content, on both undergraduate and graduate levels. Whether foundations of education, biology, environmental science, science methods or service learning, students have performed community service projects, mostly related to sustainability in some way. The vast majority of students come away with a better sense of the impact they can have on their community, the environment and others, human and other living things.

With this, my overarching goal in creating courses was to empower students to become involved and successful in community outreach and to model for them how to examine sustainability issues utilizing a full-circle perspective or a long-range view. Project-based learning about a community dilemma such as health issues related to food deserts or siting of a landfill, emphasizes the importance of developing evaluative critical thinking skills to assess a situation. By examining a product’s life cycle from all angles, all sides, and from the inception to disposal and beyond, students can make valuable contributions while learning, researching and asking key questions to delve into and find viable solutions to aid their community.

In one case, students in an introductory freshman seminar learned about the importance of recycling, creating posters and flyers to then educate others on campus. They also researched, created and conducted a survey of waste disposal behaviors on campus, presenting their findings to the larger campus community, including university administrators. This seminar was successful on several levels in that it connected incoming freshman with one another, acquainted them with campus and introduced them to faculty and staff that they may not have interacted with otherwise. In addition, it was a win-win for reducing solid waste because they became advocates for implementing a co-mingled recycling program on campus.

Another general education service learning course provided students with life-changing experiences. A key point was to allow students to learn what they need to know to be informed citizens, but to also teach them ways that they can be part of the solution. This course empowered them to become engaged and involved in creating positive change within their community. This service-learning course focused on topics related to sustainability that explored issues related to the environmental and socio-economic impacts of food production and distribution. In the nearby urban area, so-called “food deserts” exist in some areas. SRV 200 students learned that some students attending their same university were dealing with issues of food insufficiency. That is the term to describe the situation that these students did not always have the means to purchase enough food for themselves or their families. This discovery resulted in creation of a Food Pantry for that students could access when necessary.

One group of SRV 200 students were involved in establishing a Refugee Rwandan Vegetable Garden and securing donations of vegetable seedlings, compost, gardening hand tools and mulch. One student, who had immigrated from African as child, solicited donations from a local garden store, filled her car with three flats of tomato plants and other vegetable seedlings, then transported them to the site. While making adjustments for Ohio’s growing conditions, she helped the Rwandan refugees with their gardening skills. She remarked that it reminded her of learning to garden along side her grandmother as a young child in Africa. The rest of the quarter and beyond, you could find her with a scarf tied around her head, weeding, watering and interacting with the Rwandan refugees. She is still involved in making a difference and is presently attending law school, intent on practicing social justice law.

Other student groups were also involved in the local community gardening outreach efforts. Another, Student A became strongly connected to community gardening efforts in the area. As of now, 30 months later, he has established five local community gardens over the past three growing seasons. His gardens have supplied produce to several food pantries and donated vegetables to be handed out at local convenience stores in urban areas where fresh produce is not available.

“I now ride my bike more than I drive my car and I’ve started two community gardening projects to help people to grow their own food. I am much more aware of staying healthy and how we use resources.”

– Student A comment.

Yet another student (Student B) was inspired to focus her social work senior project to study the impact of a gardening program with teen offenders in a rehabilitation center (Twill, Purvis & Norris, 2011). The outcomes were very positive and even with shortfalls in funding, the program continues.

“I want to take this information and make those all important connections to 1) getting children outdoors in nature and 2) to using those experiences to help them (and their parents) to become protectors of natural habitats and good stewards of natural resources. It is about becoming aware of sustainable actions and behaviors.”

– Student B comment

Additionally, all students in this class were involved in a partnership project with urban elementary school 6th graders. Following the “Ethic of Excellence” model (Berger 2003), 6th grade students researched native trees species and plant growing needs, environmental concerns and sustainability issues related to trees. This provided a means to deepen their understanding of issues like deforestation, including a visit to the university campus and planting a tree in the WSU Woods Memorial Garden. In addition to the direct benefits, for some of these 6th graders, this was a unique experience to develop a relationship with mentoring college students, talk about why someone would want to attend college, understand how to develop a ‘life plan’ and provide an introduction to college life. The impact on attitudes and behaviors for these students in terms of acting sustainably and engaging in their community was clearly evident and indeed, became a life-changing event for them.

At Wright State University, we have incorporated community service learning into our teacher preparation programs and class requirements such as a reading tutoring program at an after school for Spanish speaking students. In an Early Childhood Science Methods course, students learned mapping technology skills to explore and capture information about local parks and play areas in their communities. They then posted descriptions and photographs that would be helpful to parents and childcare providers on Google Maps to allow them to easily find a place for children to get outside and play. At the end of the term, students saw the benefit of what they’d done and remarked that they wanted to continue to provide this service for children by seeking out additional parks and play areas and to encourage others to do the same.

Another example comes from my upper level Middle Childhood Education science course. We used sustainability-related themes like our built environment, food crops and production, energy use and transportation and natural resources with an emphasis the environmental and socio-economic impacts. Students researched, became experts, debated these topics while on a parallel track, they wrestled with how to best teach these subjects.

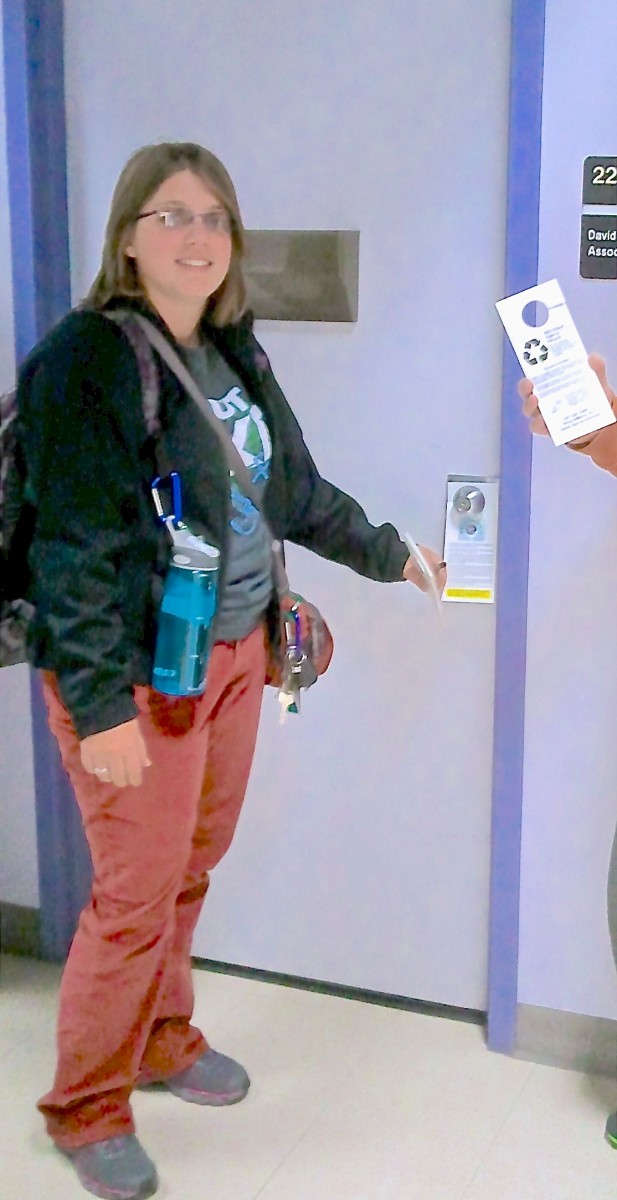

Beyond this, they prepared for and participated in the U.S. Green Building Council’s Center for Green Schools “Green Apple Day of Service”. While this was a one-day event, we spent time in and out of class on the USGBC website and reviewed examples of Green Schools to gain a working knowledge of the elements that contribute to Healthy Schools. They immediately connected with why they should know about healthy school buildings and about facility operations given that they will spend countless hours there during their teaching careers. They also came to understand what research indicated about the importance of healthy learning environments and implications for improved student achievement. We then raised the funds to have door hangers/bookmarks printed and spent several hours going door to door on campus (nearly 1000 offices!), talking with faculty and staff about sustainability and what each of us could do to Green our campus operations.

On USGBC “Green Apples, Green Schools” Day of Service.

Of course, these soon-to-be student teachers read Berger’s book and loved it. Several of them went online and found additional video clips and information about Berger’s approach to classroom teaching. Anonymous course evaluations verified that my students felt that this project-based approach to teaching was most beneficial and engaging. Nearly every student stated that it was their intend to incorporate this approach into their classroom teaching and that they wanted their students to research and find ways to Green their future middle schools.

Tossing Several Stones to Achieve a Larger Ripple-Effect

In the courses described above, students learned the requisite course content, while they became more engaged, informed citizens ¾ discovering ways that they could become part of the solution. Effective incorporation of Community-based Service Learning in classes, including teacher preparation courses, allows more opportunities for honing critical thinking skills and creation of sustained lifelong learning. Education is preparation for the future, so whether a student will become an engineer or an accountant, they can take the lessons of community service to their workplace and continue to find ways to make a difference. As Nolet (2009) points out, it is essential for teacher preparation programs to include sustainability education given the impact of classroom teachers on future generations. Educators can have additional impacts beyond potentially thousands of students that pass through their classrooms by involving other teachers in their schools (additional multiplier effect), families and community members. Combining community service learning with a project-based approach in teacher preparation courses advances us toward the goal of producing engaged, responsible citizens who understand complex environmental issues and reflect sustainability in their decisions and behaviors.

References:

Berger, R. (2003). An ethic of excellence: Building a culture of craftsmanship in schools. Heinemann, Portsmouth, NH.

Dewey, J. (1897). My pedagogic creed. The School Journal, 54(3), 77–80.

Furco, A. & Root, S. (2010). Service Learning: Research Demonstrates the Value of Service Learning Phi Delta Kappan. 91 (5): 16-20.

Hawken, P. (2007). Blessed Unrest: How the Largest Movement in the World Came Into Being and Why No One Saw It Coming. New York: Penguin Group.

Nolet, V. (2009). Preparing sustainability-literate teachers. Teachers College Record Vol. 111, No. 2, ID Number: 15177. [Online] Available: http://www/tcrecord.org.

McKibben, B. (2007). Deep Economy: The Wealth of Communities and the Durable Future. New York: Holt Company.

Sobel, D. (2005). Placed-Based Education: Connecting Classrooms and Communities. Great Barrington, MA: The Orion Society.

Twill, S. E., Purvis, T. & Norris, M. (2011). Weeds and Seeds: Reflections from a Gardening Project for Juvenile Offenders. Journal of Therapeutic Horticulture. 11(1), 7–16

Linda Ramey, Ph.D. is Associate Professor in Environmental/Science Education at Wright State University. Linda has worked in Environmental Science Education for 30 plus years earning Masters degrees in Woodland Ecology and Science Education and a Ph.D. from Kansas State University. She has worked in formal and informal science settings including: KONZA Prairie, Chicago Botanic Garden, and 15 years in environmental science education at Wright State University. She has conducted numerous workshops and professional presentations, developed outdoor education instructional materials and published extensively on environmental science and informal education topics. Presently, she is engaged in sustainability Initiatives and as Miami Valley No Child Left Inside liaison to the Ohio No Child Left Inside Initiative.

Linda.Ramey@Wright.edu

Linda Ramey, Ph.D. is Associate Professor in Environmental/Science Education at Wright State University. Linda has worked in Environmental Science Education for 30 plus years earning Masters degrees in Woodland Ecology and Science Education and a Ph.D. from Kansas State University. She has worked in formal and informal science settings including: KONZA Prairie, Chicago Botanic Garden, and 15 years in environmental science education at Wright State University. She has conducted numerous workshops and professional presentations, developed outdoor education instructional materials and published extensively on environmental science and informal education topics. Presently, she is engaged in sustainability Initiatives and as Miami Valley No Child Left Inside liaison to the Ohio No Child Left Inside Initiative.

Linda.Ramey@Wright.edu