Developing curriculum that engages students in evaluating their relationship with the natural environment

Abstract: How can curriculum at the post secondary level be used to initiate discussion and reflection for students about current environmental issues and their personal relationship with the natural environment? This is explored through student observations and analysis of personal vehicle use over a four day period. The purpose of the analysis was to engage students in understanding both their personal relationship with and modern societies’ relationship with the private vehicle and the implications of this relationship on the natural environment. The data in this study are from 24 student journals documenting their vehicle use in two winter semesters (2006 and 2007). The results from the journals show five emergent themes relevant to personal vehicle use; time, convenience, freedom, cost and the environment. Within these themes student observations included insights into the challenges associated with changing human behavior towards the natural environment at a local and global level. This paper contributes to the larger discussion about curriculum that engages students in transformative education.

Introduction

It is not enough to simply tell students of the environmental conditions of the world around them. At some point they must be engaged in understanding the values, attitudes and beliefs of a modern society shaping our consumptive behavior and subsequent disconnect with the natural environment. Orr (2004) makes the observation that curriculum plays a significant role in whether students perceive themselves as being a part of or separated from the natural environment.

In the Asia Pacific Series on Young People and the Environment, Maclean and Watanabe (2002) suggest that youth are interested in finding a balance between “modernization and tradition; between global and local concerns, and between the materialistic and spiritual aspects of what it means to be a fully functioning and socially responsible human being in the twenty-first century” (xiv).

The lens through which we view the natural world is socially constructed, and institutions such as universities are in a position to cultivate human engagement and/or disengagement from the natural environment. Therefore when educators try to change student perceptions and behavior toward the natural environment there must be some acknowledgement of the underlying social, economic and political perspectives that shape our relationship with nature.

If there is a cosmic disconnect with nature it is often visible at the institutional level. It has been two decades since the Talloires Declaration (1990) and the Halifax Declaration (1991) identifying the need for educational institutions to provide programs that would result in environmentally aware and responsible university graduates ( Herremans and Reid 2002:). By 1999 very few Universities in North America were even cognizant of these declarations let alone providing environmental curriculum in the classrooms. Although progress has been slow, 27 institutions across Canada have signed the Talloires Declaration, as of June, 2007 (Owens C, & J. Moore 2008).

Virtually all universities and colleges in Canada, to some extent, are now recognizing the importance of environment and sustainability issues and addressing them at policy and operational levels. For example, improving energy efficiency, promoting recycling and establishing campus sustainability offices are strategies to support goals of sustainability at the institutional level. However, as noted in the literature (Wackernagel and Rees, 1995; Orr,2002) issues of sustainability are often approached by institutions as technical problems without any consideration for the underlying human values at the root of our environmental crisis. It is precisely this sort of thinking that has helped to create our current environmental crisis and it is precisely this type of thinking that is unlikely to help solve our problems.

While it is important to implement campus sustainability at the policy and operational levels it is just as important to include sustainability in teaching and research initiatives (Owens C, & J. Moore 2008). Therefore, curriculum that engages students in discussion and reflection can provide a different lens through which to view the natural world and ultimately create a different outcome. Discussions about advancing education for sustainable development have been gaining momentum on an international level. For example, conference proceedings from the 4th International Environmental Education Conference, held from 24–28 November 2007 at the Center of Environmental Education (CEE) in Ahmedabad, India include a discussion of pedagological strategies to support a more experiential and engaging form of education. The proceedings suggest that advancing education for sustainable development will require a move from more traditional transmissive education to more transformative education.

In the past it was common practice among various disciplines at universities to maintain the exclusivity of their own subjects; in effect creating a division across campus and among faculties. As a result the most students who graduate from modern institutions of higher learning do not have an understanding of how integrated the world is (Orr, 2004). If students only understand the subjects of their particular discipline how are they to ask larger questions of the human condition? How are they to understand the relationship between livelihood governed by politics, economics and social/cultural systems within a natural world governed by ecological systems? How are they to know that individual and collective actions can make a difference?

The following is an example of pedagogical strategy that was used to advance experiential and engaging forms of education. Student reflections of their personal relationship and modern societies’ relationship with the private vehicle provides a foundation for a larger discussion about the value of transformative education. This assignment came about when the topic of Yosemite’s Area Regional Transportation system (YARTS) was introduced to the students. In class, we were discussing strategies to get travelers to use public transportation instead of their private vehicles in national parks such as Yosemite. However, it occurred to me that we, as a class, needed to move beyond talking about transportation strategies and actually experience what the travelers would experience. We decided to leave our private vehicles at home for a 2 day period, document the experience and then discuss transportation strategies and the challenge of changing modern society’s love affair with the private vehicle.

In Canada many people consider their cars absolutely essential to carry on their daily activities such as; commuting to and from work, shopping for dinner, transporting kids, getting to appointments and evening engagements. However, wide spread use of private vehicles in urban centers in Canada and other Western Countries is having an impact on the environment and personal health. For example transportation is a large contributor to greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions (Turcotte, 2008; Environment Canada 2006). In a recent Environment Canada Report (2006), the growing popularity of sport utility vehicles and pickup trucks were identified as being significant contributors to the increase in GHG emissions. Additional concerns related to increased personal vehicle use is smog associated with GHG emissions, an increase in traffic congestion and the associated increased costs for building and maintaining roadways (Turcotte, 2008). Given these circumstances and an increase in public awareness, it is understandable that there is a call for more environmentally friendly modes of travel such as walking, biking, car pooling and public transportation (Turcotte, 2008).

Methodology

In 2006 and 2007, Students submitted journals in partial fulfillment of course requirements in a second year environmental issues in tourism class at Thompson Rivers University, Kamloops B.C. At the end of the winter semesters in 2006 and 2007, students were asked to voluntarily resubmit their journals for the purpose of this study. Twenty four journals were submitted as part of this study. Emergent themes from student observations are discussed and supported by frequency tables and student’s anecdotal observations.

Students inventoried and documented how often they used their vehicles and for what purpose over any two-day consecutive period during one work week. Also, they documented the advantages and disadvantages of using their vehicle. During this first week students created a baseline of their activities. The following week students were required to change their behavior. They were directed to leave their vehicles at home for the same 2 days of the week noted in journals for week one, and either take public transportation, walk or make use of non-motorized transportation to their destinations. During this time students documented advantages and disadvantages of not using their vehicles in a journal format. They also identified methods or incentives that could be used to address environmental problems associated with vehicle use and explain the challenges to changing human behavior toward using private vehicles. Finally, students applied their findings to a tourism setting such as a National Park and explain how they would reduce the impact of fossil fuel emissions in national parks while maintaining visitor satisfaction at the same time. Students also had the option to apply their findings to an urban setting and explain what incentives could be used to encourage the general population to reduce their vehicle use. This paper does not include observations made in and applied to national parks.

A content analysis of the (students’) journals was conducted to identify and organize emergent themes. The process of identifying the emergent themes began by reading all of the journals (several times) and observing (key) words and phrases used repeatedly by the students (related to the four assignment requirements): advantages of personal vehicle use; disadvantages of personal vehicle use; incentives (for changing behavior); and challenges for changing behavior. (Based on the key words and phrases), a frequency chart was developed for each of the four topic areas. Results were tabulated and categorized to organize the content and pull out the emergent themes in each of the four topic areas. For example student reference to waiting for the bus, the duration of the bus ride or restricted bus schedules were tabulated as either an “advantage” or a ”disadvantage” under the theme “time”. The frequency of the phrases or words associated with time was tabulated and is presented in the results section of this paper.

Results and Emerging Themes

The results from the journals show five themes related to the advantages and disadvantages of personal vehicle use; Time, Convenience, Freedom, Cost and the Environment. These five themes are discussed in the following section.

Advantages of owning a vehicle.

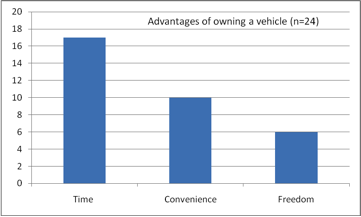

As indicated in Figure 1, students identified time and convenience as the most significant factors influencing their mode of transportation followed by freedom. In reference to time, students consistently noted that they spent less time getting to their destinations when using a vehicle. They also identified the importance of spontaneity and freedom of choice associated with having a vehicle.

“By partaking in this experiment, I have come to realize just how dependent I have become on my truck in just five short years. In situations such as going to the store for food, or going to rent a movie, which are in very reasonable walking distance, I often choose to drive instead partially for the speed in which I can get things done and also because of pure habits I have developed”.

Six of the 24 students participated in sports or planned their day to include a workout, consequently it was important to them that they were able to carry more “stuff”. Students noted that without a vehicle they would be restricted in their activities due to the amount of books and personal gear they would need to carry. One of the six students summed it up this way:

“Driving my car is a quick and convenient way for me to get around. However I rely on my car as a travelling locker. I leave my gym bag in my car all day and I pack a lunch. When I take the bus next week I will not be able to go to the gym or pack my own lunch because the bags are too large to carry. Furthermore, I only have a limited amount of time to go to the gym, work out and then walk back in time for class”.

Other students involved in recreational activities noted that access to the ski hill was important as well as the flexibility to be able to go on their own without relying on others. Once again a sense of freedom emerged as an important consideration for this group of students. The ability to carry groceries was also identified as an advantage of having a vehicle.

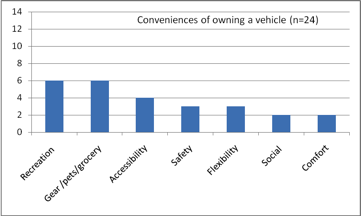

Seven themes relevant to the students perception of convenience emerged from the journals (Figure 2). Responses directed at social conveniences were primarily focused on the ability to offer other people rides and to be able to meet friends at prearranged times or destinations. Flexibility was often mentioned in conjunction with freedom in that students were referring to the ability to use their vehicles when they wanted.

Disadvantages of owning a vehicle.

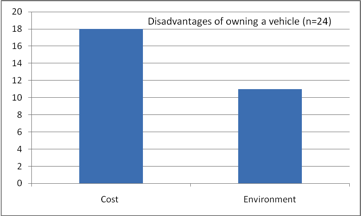

Two primary themes; cost and the environment, emerged as disadvantages of owning a vehicle. (Figure 3). Fifty percent of the students who identified impact on the environment as a general concern also included emissions as a specific concern.

“the other major disadvantage of using a car is the pollution you are adding to the environment. Most people think something should be done to reduce emissions, but it is always in the back of our minds, as convenience of owing a vehicle greatly out weights the thought”.

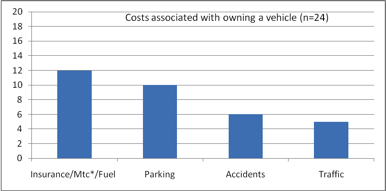

Fifty percent of the students identified insurance, maintenance and fuel as the primary costs of owning a vehicle. Other concerns included parking on campus and resulting parking tickets when applicable. With regard to traffic, this variable is likely dependent on where a student lives, infrastructure and the density of the population using private vehicles.

Disadvantages of alternative forms of transportation.

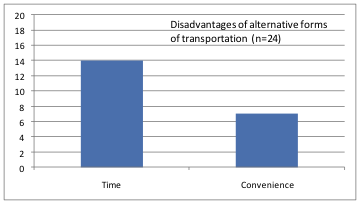

When students were required to leave their vehicles at home and take alternative modes of transportation, time and convenience were the primary themes that emerged (Figure 5).

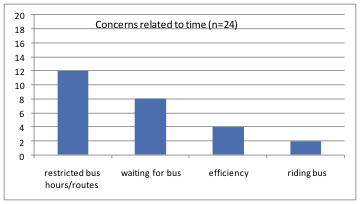

Without a vehicle students documented their frustration in having to rearrange their schedules and change their routines. In particular getting out of bed earlier to catch a bus was a common observation in the journals. In regards to time, the primary concerns noted by students included waiting for the bus, being restricted to bus hours, schedules and routes and efficiency. (Figure 6) The following quote sums up common concerns related to both time and convenience as noted in the journals.

“Walking and taking the bus is a lot more time consuming than driving. I spent a lot of time waiting for buses or leaving earlier than I normally would because of the schedule. Sometimes the bus didn’t come when I needed it so I would have to leave earlier and then I would be at my destination earlier then I needed to be”.

With regard to the environment 20% of the students mentioned the weather as a disadvantage when having to walk or wait for the bus.

“I thought about riding my bike to school but the weather is just too cold and to walk would have taken me about 2 hours. So instead I chose to take the bus… not just one but three buses to get to school”.

Other observations made by female students included safety concerns while waiting for the bus at night.

The most frequent complaint documented in student journals was that more time was spent on alternative forms of transportation than was actually spent at the final destination. Time spent waiting for the bus or the indirect route taken with public transportation was identified most often as a disadvantage of not having a vehicle. Approximately 25% of the students also noted that last minute changes were hard to accommodate and extra planning is a consideration when taking alternative forms of transportation. However, a few students recognized that extra planning could be beneficial.

“It took a bit more time to go out and do the things I needed to do and I had to plan ahead instead of hopping in my car and getting it done. It is just a bit less convenient to have to plan ahead but it made me more efficient with my time”.

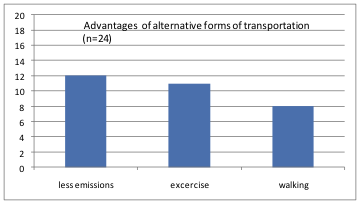

Advantages of alternative forms of transportation

Students identified “cost savings (58%) and concern for the environment” (42%) as two primary advantages of using alternative transportation. With regard to the environment students identified lower emissions (50%) as the primary advantage of leaving their vehicles at home. Getting exercise (46%) and walking (34%) were also recognized as personal benefits (Figure 7). In addition, feeling awake and alert when arriving at the University were identified as advantages of walking.

The five themes, time, convenience, freedom, cost and the environment, that emerged from the student journals are not surprising given our reliance on the private vehicle as a necessity to maintain the status quo of convenient lifestyles and high levels of consumption. In the following section student observations regarding challenges to changing human behavior and possible incentives are discussed.

Challenges to changing human behavior

Many of the student observations support the arguments for and against changing human behavior as presented in the literature. For example consumer behavior survey questionnaire results indicate that consumers “attach considerable value to the interests of nature and the environment when making consumer decisions” (De Geus, 2003 p. 150). However it is also evident that in daily practice “most of the citizens -as daily consumers- are only prepared to accept relatively small behavioral changes that do not deeply affect their basic lifestyle and only demand little effort” (De Geus, 2003 p. 150). A sagacious insight from one student shows the fundamental reality of consumer decisions regarding vehicle use:

“We all would like to say that we do our part in helping the environment. However, the convenience of having something to help us make life easier is just too hard to pass up, and we are willing to sacrifice the wellbeing of our planet for it”.

In our current liberal western democratic society, pursuit of individual wants and desires have been heralded as the foundations for a healthy lifestyle and vibrant economy. Consumption and lifestyle choices are in the individual domain and it is rare that consumer decisions are based on the greater good of the wider community. According to deGeus (2003) “interviews and data research have shown that an over riding majority of respondents perceive car mobility and airplane holidays as ‘private’ activities that do not belong to the public domain of morals and are not to be regulated by social instruments” (p.149). Although individualism is empowering in terms of lifestyle choices and pursuit of happiness in a consumer society, it is also limiting in how we perceive the results of our actions. The issue of one individual’s ability to make a change was noted by one of the students.

“I rarely take into consideration the effects my actions have on the environment around me. I am often hounded by my sister about my needless driving tactics, but seem to take the outlook that I singly cannot have an impact on the environment.”

In today’s global world market incentives are often regarded as the best methods for encouraging a change in consumer patterns. Students also identified market incentives as the only possible way citizens would change their behavior toward private vehicle use.

“Getting people to leave their vehicles at home and use alternative methods of transportation is a difficult task. After using and relying on vehicles for so long, taking public transportation seems very time consuming and inconvenient. Some incentives are definitely required to encourage people to leave their cars behind. I think that these incentives must be drastic because of our reliance as a culture on our vehicles. Although public transportation is fairly inexpensive, I believe that it would have to be free for people who have cars to use it”.

Many students made the observation that as long as global warming remains as some unseen condition people are likely to ignore it or not take it seriously. One student suggested that as long as people are not directly affected by global warming they are unlikely to change.

“Currently there are not enough incentives for people to leave their cars at home. I personally don’t think that incentives will be implemented until environmental damage from CO2 emissions has a more direct impact on the individual. And even then, because of such a heavy reliance on our vehicles, people would rather plant one tree a week than walk 10 minutes to a bus stop”.

Discussion

The students perceptions of and behavior toward the use of personal vehicles is reflective of underlying social, economic and political values of Western Democratic societies. We live in a consumptive society and fulfillment of ones desire for more and more consumer goods is similar to an addictive drug; it is “harmful to the individual and our natural environment, since it eventually leads to ecological unsustainability” (de Geus. 2003 :16) However, as the students pointed out, the global impacts of personal vehicle use is not as important as maintaining a lifestyle of convenience. So how do we make the connection between the health of the planet and our individual actions? What role does education play in this process of change? Lidstone and Stoltman (2008) resoundingly state that we are not educating today’s generation of students for the future global changes that will inevitably occur during their lifetime. Not only will individuals be faced with global changes, so too will societies and regions throughout the world (Lidstone and Stoltman 2008). One of the challenges associated with education is that often curriculum development occurs at a slower rate than environmental change (Lidstone and Stoltman 2008) This is not easy to change, however what is changing is the lens through which we look at the natural environment and purpose of higher education. Traditionally universities have been viewed as institutions that exist to service the economy and provide the skill base needed for future society (Gough & Scott 2007). However there is an emerging view that suggests universities have a larger role to play in contributing to the “intellectual and moral improvement of the human condition” (Gough & Scott, 2007: 1)

Herremans and Reid (2002) identified two ways educators can improve environmental curriculum. The first was to develop content that identifies “variables most influential in motivating individuals to be responsible environmental citizens” (Herremans and Reid 2002: 17). The second is to “integrate environmental content in every school program as either a separate course or as part of existing course content or both”(ibid:17). However this author argues that we no longer have the luxury of discussing the environment as a separate topic and it needs to be integrated into the curriculum across disciplines.

If education is to be effective, the content must provide students with an opportunity to analyze the underlying human values shaping their current relationship with and behavior towards the environment. Specifically, content that includes experiential learning and analysis of human values across disciplines could result in a new perspective toward the current environmental challenges facing human kind. In Canada, Dalhousie University is a leader in providing a practical, student focused, collaborative approach toward issues of sustainability. Drawing on experts from the community and across the faculties at Dalhousie, the Environment, Sustainability and Society Program (ESS) inspires new ways of thinking about sustainability and society through an interdisciplinary model that transcends traditional approaches to research and education.

The role of universities in promoting sustainability throughout the curriculum, in research and in self-management is both relevant and timely. A case in point is a province wide initiative to promote sustainable education at post secondary institutions in British Columbia. In two- day workshop, May 18-19, 2010, held at UBC, Simon Fraser Campus, educators gathered from institutions across the province to work though the challenges of incorporating sustainability across the curriculum. Participants came away from this workshop with tools, resources and support groups to initiate change toward sustainability in their home institutions beginning with their own courses.

In this authors opinion our relationship with the environment will change only when we start thinking about things differently. Did the journal experiment result in a change in student behavior? Was it transformative? Probably not, but what it did was take the theories of environmental change and bring it down to a practical level where students could analyze their values and societies values in shaping our relationship with the natural environment. Instead of being told what to think or how to act, students were given the opportunity to be participant learners, resulting in a greater understanding of the complexity of issues of sustainability. Consequently, students who graduate with a broad, integrated sense of the unity of things are in a better position to understand their personal role as stewards and citizens of the larger biotic community.

Recommendations for further study.

This study was exploratory in nature and relied on student observations and anecdotal evidence collected over a four day period. Future adaptations of this assignment could include expanding the experiment to a two week duration. An extended time line would give students more time to experience public transportation options. Another adaptation could include a cross cultural communications component where domestic students interview international students and vice versa to compare how the vehicle is valued across cultures. This cross cultural insight evolved organically through student participation in class discussions at the end of the experiment. For example one student who is in residence on campus described how he easily could walk from his home to his classes. However, he explained that his decision to drive 2 km around campus looking for a parking space was more cultural than anything else. He explained that in his culture the vehicle is a status symbol and it was better to “be seen” driving than walking.

Further studies of personal vehicle use and alternative transportation options in small cities and large urban centers could be conducted for comparative purposes. Specifically, this study relied on students attending Thompson Rivers University, located in Kamloops, a small city in the interior of British Columbia with a population of 85,000 and limited public transportation options. The literature suggests changing human behavior toward private vehicle use may be easier to address in larger city centers with higher population density and less urban sprawl.

Bibliography

Bell, Michael. M. (2009) An invitation to Environmental Sociology (3rd Ed) Thousand Oaks California. Pine Forge Press.

Bowers, C.A. (2003) Mindful conservatism : rethinking the ideological and educational basis of an ecologically sustainable future. Lanham , Maryland. Rowman and Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

Berry, Thomas (1988) The Dream of the Earth. Sierra Club Books.

Commoner, Barry (2002) Contribution to the Environmental Movement. Amityville, New York. Baywood Publishing Company Inc.

Cranton, Patricia (1994) Understanding and Promoting Transformative Learning. California, USA. Jossey- Bass Inc., Publishers.

de Geus, M. (2003) The end of Over-consumption. Netherlands, International Books.

Environment Canada (2006). National Inventory Report – Greenhouse Gas Sources and Sinks in Canada, 1990-2004. Ottawa: Minister of the Environment.

Gough, S. & Scott, W. A. H., (2007) Higher Education and Sustainable Development: Paradox and possibility. Taylor and Francis e Library.

Guber, Deborah. L. (2003) The Grassroots of a Green Revolution: Polling America on the Environment. Cambridge, Massachusetts. The MIT Press.

Hayes-Conroy, J., & Vanderbeck, R. (2005). Ecological identity work in higher education: Theoretical perspectives and a case study. Ethics, Place and the Environment, 8(3), 309-327.

Hawkin, P., A. Lovins & L.H. Lovins. (2000) Natural Capitalism: Creating the Next Industrial Revolution. USA. Back Bay Books.

Head, Lesley (2000) Cultural Landscapes and Environmental Change. Oxford University Press. New York, NY.

Herremans, I. M. & R. E. Reid (2002) Developing Awareness of the Sustainability Concept.The Journal of Environmental Education. Vol 34 No1.

Humphrey, C.R., T.L. Lewis & F.H. Buttel (2001) Environment, Energy and Society: New Synthesis. California USA, Wadsworth Thompson Learning.

LeCompte, M. & J.J. Schensul (1999) Analyzing and Interpreting Enthnographic Data. Lanham, New York. Altamira Press.

Lidstone, J. and J. Stoltman (2008) Global Environmental Change: What is the Role of Geography and Environmental Education? International Research in Geographical & Environmental Education; Vol. 17 Issue 2, p89-92.

Louv, Richard (2005) Last Child in the Woods. North Carolina. Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill.

Lucia, A. & I. Ropke (eds) (2004) The Ecological Economics of Consumption: Current Issues in Ecological Economics. Cheltenham, UK. Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd.

Maclean, R. & R.Watanabe (2002) in Fien, John, David Yencken and Helen Sykes (Eds) Education in the Asia Pacific Region Series: Young People and the Environment. An Asia – Pacific Perspective. Netherlands. Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Orr, David W. (2002) The Nature of Design; Ecology, Culture and Human Intention. New York, N,Y Oxford University Press.

Orr, David W. (2004) Earth in Mind: On Education, Environment, and the Human Prospect. Washington DC: Island Press.

Owen, Tom. (2009) Director of Environment and Sustainability, Thompson Rivers University, Kamloops B.C. Personal communication.

Owens C, & J. Moore (2008) Taking Stock 2008: The Current State of sustainability in British Columbia Universities and Colleges.

Prugh, T. R Costanza & H. Daly (2000) The Local Politics of Global Sustainability. Washington, D.D. Island Press.

Rennie, S. (2008) Toward a 21st-Century Understanding of Humans’ Relation to Nature: Two Hats? The Journal of Environmental Education. Vol. 40 No1.

Shor, Ira (1992) Empowering Education: Critical Teaching for Social Change. Chicago. The University of Chicago Press,

Sobel, David. (2005) Place- Based Education: Connecting Classrooms and Communities. Great Barrington MA. The Orion Society.

Stern, P.C., T. Dietz, V.W. Ruttan, R.H. Socolow & J.L. Sweeney (Eds) (1997). Environmentally Significant Consumption: Research Directions. Committee on the Human Dimensions of Global Change. Commission on Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. National Research Council. Washington. D.C. national Academy Press.

Thomas, Berry (1999) The Great Work: Our Way Into the Future. New York: Bell Tower.

Turner, Nancy J. (2005) The Earths Blanket: Traditional Teachings for Sustainable Living. Vancouver .B.C. Douglas & McIntyre.

Wackernagel, M & W.E. Rees (1995) Our Ecological Footprint: Reducing Human Impact on the Earth. New Society Publishers. Gabriola Island, B.C.

Wainwright. J.A.(Ed). (2004) Every Grain of Sand: Canadian Perspectives on Ecology and Environment. Waterloo. Ontario. Wilfred Laurier University Press.

Wilson, Edward O. (2006) The Creation: An Appeal to Save Life on Earth. New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

Robin Reid is an Assistant Professor in the Faculty of Adventure, Culinary Arts and Tourism at Thompson Rivers University, Kamloops B.C. where she is a principle investigator in mapping and exploring the role of community and public produce gardens as spaces for public engagement, sustainability and connection to place. Robin’s academic background and teaching experience in sustainability and tourism have guided her research interests in, cultural narrative community, sustainability and sense of place in urban, rural and wilderness landscapes.

Robin Reid is an Assistant Professor in the Faculty of Adventure, Culinary Arts and Tourism at Thompson Rivers University, Kamloops B.C. where she is a principle investigator in mapping and exploring the role of community and public produce gardens as spaces for public engagement, sustainability and connection to place. Robin’s academic background and teaching experience in sustainability and tourism have guided her research interests in, cultural narrative community, sustainability and sense of place in urban, rural and wilderness landscapes.