Critical Sustainability: Promoting Pedagogies of Placefulness in Outdoor Education

Abstract: The socioecological challenges we face have never been so complex, so intractable, and so urgent. And while both justice-oriented education and education for sustainability are growing in colleges and universities across the United States, normative perspectives of outdoor experiential education have fallen embarrassingly behind. In this paper, we offer critical sustainability as a conceptual basis for engaging students in the beauty, perversity, and complexity of our world. Critical sustainability, integrating sociopolitical systems of privilege and oppression with the socioecological imperatives of global health and justice, provides an exciting and promising pedagogical direction. With this conceptual framework, we explore perspectives of “nature,” placefulness, and our multiple, overlapping subjectivities as students, educators, and engaged citizens. Our task as outdoor educators is to bring the faraway nearby and inspire students to engage in the myriad challenges we face as individuals, citizens, and as members of a global ecological community. We conclude by offering place mapping as a pedagogical technique to support elements of critical sustainability in outdoor education settings and beyond.

Key words: environmental justice, mapping, outdoor education, place, social justice

Introduction

Stated mildly, critical assessments of the current state of the planet do not illustrate an image of enduring health. Social unrest, political brinksmanship, and economic insecurity receive media and popular attention, while seemingly without notice, the ecological integrity of the planet has been extended beyond its breaking point. Root causes of these injustices are deftly hidden, yet simultaneously and paradoxically readily recognizable. The expansion of neoliberal capitalist accumulation, often termed simply and benignly as “economic growth,” is solely reliant upon the conversion of the material planet – nature – into the means of production and product itself, while the perpetration of social and ecological injustices are considered unfortunate byproducts. With one in six humans currently living in slum conditions (Davis, 2004; 2006), the social and ecological destitution facing the planet is nothing short of a crisis (Buell, 2003). However, embedded within this crisis is reason for hope: with the material inputs and the energy intensive nature through which it is operated, “capitalism is effectively running up against its planetary limits” (Wainwright & Mann, 2013, p. 8), indicating that we will need a new global political economy in the coming decades (Exner et al., 2013; Li, 2008; 2010). Whatever the future might hold, from an environmental, social, cultural, or political economic perspective, we can only know that it most certainly cannot look like our current situation, which is definitively unsustainable (Williams, 2010).

How, then, is it appropriate to critically respond to such a seemingly dire analysis of the current social, political, economic, and environmental world order? Regardless of one’s critical epistemological orientation, be it Marxist, poststructuralist, posthumanist, feminist, critical race, or especially Freirean, a justice-oriented movement or re-envisioning of our social, political, and ecological world cannot progress without significant change from our educational and pedagogical processes. Our existing educational practices are clearly failing to effectively promote and nourish notions of justice, equity, and ecological sustainability in our students, who are ultimately both citizens and decision-makers. It seems necessary, then, to question all levels of formal and informal education as to how we can create a stronger, more egalitarian, and more just socioenvironmental world.

Experiential education generally, and outdoor education more specifically, tends to be ahead of many traditional educational institutions in both content and pedagogy concerning issues of justice and sustainability (Cachelin, Paisley & Dustin, 2009). Yet, there is little support to suggest that outdoor education courses are actually serving as critical venues for students to change behaviors, to become more critical and democratically engaged citizens. This shortfall of outdoor education is particularly disappointing considering its potential for connecting students to the social and environmental landscapes around them, from the immediacy of local systems to the complexity of global ones. This article explores the roots of this issue, examining outdoor education and its connections to social justice and sustainability as one and the same. We then offer a series of proposals for ways in which outdoor education can better address these critically interconnected issues. Mapping activities, which foster understandings of space and place, offer promise as a pedagogical tool that can attend to the most pressing issues of our time by exposing the faraway as nearby and helping students understand the complexity and scale of the challenges we face. We conclude with a contextualized example of how commonplace outdoor education philosophies such as Leave No Trace fall short in addressing the intersection of ecological and social justice inherent in critical sustainability. If the day of reckoning is near for our capitalist-induced socioenvironmental crises, then outdoor education, in addition to many other institutions, is well advised to productively and appropriately consider and respond to the various injustices that our current political economy so actively promotes.

Experiential and Outdoor Education

Experiential education takes a wide range of forms in North America, with outdoor education being one of many manifestations. For the context of this argument, we define outdoor education as intentionally designed experiences that use the outdoors as the primary medium in which learning occurs. These experiences often take place in adventure settings and/or in expeditionary settings. Common institutional structures for outdoor education include grade schools, college and university programs, non-profit schools, for profit schools, and for profit private companies, among others.

Issues of sustainability take different curricular and practical forms in different outdoor education settings. While some educational institutions incorporate greater or fewer elements of sustainability into their curricula (e.g., Moskowitz & Ottey, 2006; Sherman, 2008), most schools have yet to prioritize sustainability as a learning outcome. Instead, most programs contain a curricular element concerning environmental stewardship and often this stewardship is limited to the setting of the program itself. This classically liberal notion of environmentalism is founded in Judeo Christian and romantic notions of nature as a benign and providential construct, with humans as the guilty violators of earth’s inherent sacredness (Dowie, 2009; Kates, 1987; Kay, 1989; White, 1967). In it, there is a seemingly sentimental desire to return to a natural balance between humans and the non-human world around us, even if such a relationship never really existed (e.g., Cronon, 1983; Mann, 2005; Rawson, 2010). A prominent manifestation of this often unquestioned ideology can be found in nearly all expeditionary or backcountry-based outdoor education programs’ incorporation of Leave No Trace (LNT) principles. LNT is often presented as a sort of pedagogical panacea for teaching environmental ethics, a somewhat limited perspective that is addressed in more detail below. From our perspective, critical sustainability in experiential/outdoor education must reach beyond a localized stewardship given the global impacts and their ramifications for social and ecological justice.

Social Justice

Social justice has gained increasing consideration in academic literature over the past two decades (Denzin & Lincoln, 2013), with outdoor and experiential education literature providing brief, but inconsistent, attention (e.g., Bowdridge & Blenkinsop, 2011; Brown, 2002; Cachelin, 2010; Martin, 1999; Nagda, Gurin, & Lopez, 2003; Rose & Paisley, 2012; Warren, 2005). Although definitions across contexts vary substantially, most definitions of social justice refer to an organization of society and politics that focuses upon rights, dignity, equity, and respect of all parties involved. Social justice is also a process, or work, of infinitely “articulating needs and aspirations within a democratically organized social space” (Hartnett, 1998, p. 233). Efforts toward social justice actively interrupt systems of oppression that are rooted in culture, history, and economics (Rose & Paisley, 2012). Social justice has grown to explore and address tensions among individual and institutional inequities by complicating and indicting various social, political, and economic systems and institutions (Harvey, 2009). Social justice is not a single, definable goal as much as it is an incomplete process, as there are always continuous avenues for critical engagement (Ladson-Billings & Donnor, 2008). A critical perspective incorporating social justice necessarily implicates not only the systems that support and maintain oppression, but also those of us living largely free from oppression, as unwitting oppressors living out our own privileges (Evans, 2010; Rose & Paisley, 2012). In this sense, systems thinking is foundational to the development of a critical perspective for both ecological and social justice. And as such, critical perspectives on the world should not discount the possibility that the paths toward social justice rely, in part, on reducing the privileges of those who are already most fortunate. Outdoor education has powerful potential in this role given the justice-oriented democratic spaces that are generated in program spaces and the potential for transfer. In this sense, unmasking oppression as an explicit outdoor/experiential education goal calls on us to simply take a broader view of our own roles in globalized socioenvironmental system and attend to these at broad scales.

Sustainability

While it is rarely acknowledged, we are currently in the United Nations designated Decade of Education for Sustainable Development (2005-2014), intended to integrate the principles, values, and practices of sustainable development into all aspects of education and learning to encourage changes in behavior that help create sustainability. This laudable goal, however, remains opaque in light of numerous critical questions: What is sustainability? Sustainable for whom? Sustainable at what cost? Sustainability within what political economic system? And germane to the topic at hand, the role of outdoor education in support of sustainability or sustainable development also remains an unanswered question.

Numerous definitions of sustainability exist, depending upon the environmental, social, political, and/or economic context (Curran, 2009; Rosen, 2009a). The avenues of academic inquiry into sustainability are growing steadily (Liu, 2009), with different researchers emphasizing different aspects of the widely-invoked construct. Demographics (Barrett & Odum, 2000), agriculture (Losada et al., 2001), energy production (Rosen, 2009b), and conservation studies (Hoag & Skold, 1996), among others, represent the diverse areas of inquiry into sustainability. Zimmerer (2000) illustrated the geographic perspective of understanding nature-society relations through a critical lens of sustainability and conservation. Sustainability is often characterized, graphically, as three overlapping ellipses, typically labeled people, planet, and profit (Elkington, 1997; Fisk, 2010). From this perspective, sustainability is only possible where all three outlooks converge, focused into a single, clear, and integrated vision. This perspective on sustainability generally comes from business and corporate perspectives, where other versions of the sustainability Venn diagram use the words environment, social, and economy (Rasul & Thapa, 2004), a less directly capitalist vision. Sustainability is often critiqued for masquerading as a tool for extending inherently unsustainable capitalist development (Dietz & Neumayer, 2007; Williams & Millington, 2004).

These multitudinous definitions notwithstanding, we largely adhere to Liu’s (2009) definition of sustainability as “living within one’s own ecological means” (p. 1422). The concept of living provides for the provision of basic human needs for life, but not necessarily everything one needs or wants. The second part of the definition, one’s own ecological means, is “determined by one’s own carrying capacity locally or regionally and indicates a geographic dimension” (Liu, 2009, p. 1422). “One,” in this definition, can transcend across scales and become a single individual, a single community, a single region, or perhaps the entire planet. Liu’s (2009) definition of living within one’s own ecological means is not, however, without fault. There remains an element of subjective interpretation when determining what “one’s own” means are, and these are certainly variable (within ecological limits) across time, place, and culture, the last of which accounts for various technological achievements that certainly influence sustainability. Living within one’s ecological means requires that all species – including humans – adhere to the fact that a one-size-fits-all prescription for lifestyles, consumption, distribution, development, and disposal of wastes is inherently unattainable, that these aspects should be addressed differently across different socioecological systems.

What, then, might it mean to “live within one’s own ecological means” during an outdoor education experience? Certainly this proposal accounts for not exceeding the carrying capacity of the supporting ecosystem(s), as well as attending to the various environmental constraints. Certainly it calls on outdoor educators to reach beyond our immediate backcountry circumstances when we consider an issue such as carrying capacity. And further, outdoor educators tend to seek transference of knowledges, skills, and experiences (Priest & Gass, 2005), indicating that they should also be consider the concept of living within one’s own ecological means beyond the scope of an outdoor education course as well.

Critical Sustainability?

Issues of social justice and sustainability ultimately cannot be separated from one another (Cachelin, 2010). Evans (2011) illustrates that critical perspectives on social justice implicate all of us in sociopolitical, socioeconomic, and sociocultural relations, and that moving toward a more sustainable world requires a hyper-inclusive notion of our socioenvironmental impacts at multiple scales. Many notions of sustainability include social equity, along with economic prosperity and environmental quality, as one of three pillars that support sustainability (Adams, 2006). Duxbury (2004) suggests that there cannot be sustainable communities without an embedded notion of social justice. Social justice is “broadly about the distribution of benefits and burdens” (Foley, 2004, p. 2), similar to most common conceptions of environmental justice.

While “sustainable development” is often indicted for its role in environmental justice issues and these critiques have their obvious merits concerning (green) consumption as a path forward, it is not only private consumption that promotes human flourishing, but also a range of other “goods” that people enjoy but do not personally purchase. Clean air, decreased vehicular traffic, and open spaces free from pollution, among many others, fall into this category. Such perspectives have long resided within broader environmental justice movements (Holifield, 2012). Sustainability, then, clearly is informed by environmental justice issues that are inextricably and simultaneously issues of social justice (Di Chiro, 1996), leading some to propose a broader, more all-encompassing definition of socioenvironmental justice (Rose, 2013), or, perhaps more concisely and more simply, “justice,” which must ultimately be informed by an ecological or systems-based narrative (Cachelin, 2010). In this context, the notion of development takes on a qualitative rather than quantitative connotation as quality of life is enhanced by environmental amenities like clean air and water and open spaces as well as social equity. This sentiment is echoed by Harvey (1996) who suggests “sustainable development,” should clearly remove itself from the measurable imperatives of capitalist accumulation, and focus instead on the development of quality of life for all humans and non-humans alike (Harvey, 1996). Ultimately, any notion of social justice is reliant upon sustainability, just as any notion of sustainability is reliant upon a quest for social justice.

Critical sustainability is a concept that encompasses interconnected notions of sustainability and social justice. It recognizes the material, ecological necessities that sustain all life on the planet, while also acknowledging and seeking out sociopolitical orientations that support dignity, equity, respect, and rights for all parties. It refuses to accept the super ordinance of either environment over human equity or vice versa, recognizing humans as a part of ecological systems or humans as “nature with consciousness.” Sustainability, in all of its multitudinous definitions, has often become too qualified, too quantified, and too embedded into the various circuits of consumer capitalism to offer any productive path forward. Critical sustainability, on the other hand, explicitly refutes commodification of “nature,” seeking instead a biopolitical organization of social life that envisages human flourishing as fitting well within the limits of larger ecological systems. Outdoor education, and certainly the world beyond outdoor education, needs to adopt critical sustainability as a programmatic goal to unmask the systems of oppression which we depend on for the creation and maintenance of our outdoor experiences.

Proposals for Outdoor Education

Outdoor education needs to recognize its seemingly limitless potential to promote these interconnected notions of sustainability and justice. From a social perspective, outdoor education experiences have tremendous metaphoric potential as microcosmic representations of society at large (Hunt, 1994). Outdoor education courses often take place over multiple days where groups can form their own values, their own norms, and are directly responsible to other group members for the success of the expedition (Furman & Sibthorp, 2011). On these experiences, group members can create, implement, and practice their own notions of justice. Outdoor education, “as a metaphoric practice, can be ideally suited to model and facilitate social justice and should work to do so” (Rose & Paisley, 2012, p. 151). Further, outdoor education is an excellent microcosm to flesh out a variety of power discrepancies (Bowdridge & Blenkinsop, 2011), including those differentials that exist between people and the world around us, between society and nature (Baker, 2005; Martin, 1999).

These nature-society tensions constitute some of the fundamental existential questions of what it means to be human (Pattison, 1990), and the relationships between nature and society have constituted scholarly and philosophical inquiry for centuries (Zimmerer, 2000; 2010). Outdoor education, almost inherently, offers connections to place (Baker, 2005; Knapp, 2005), enabling students to develop and inform their relationships with the places they inhabit during the outdoor learning expedition, and, hopefully, with the places they inhabit well beyond the duration of their formal outdoor education experiences. Outdoor education has the possibility to inculcate this type of metaphoric transfer, a pedagogy that uses “similar processes” (Priest & Gass, 2005, p. 186) of learning from one setting in another. Outdoor education should be directly (and indirectly) addressing sustainability, justice, and connection to place as part of creating a more just and healthy world, one in which we all are “living within one’s own ecological means” (Liu, 2009, p. 1422). Specifically, outdoor education should engage in three processes: it should re-envision the context of the role of humans as part of a larger ecological system (Cachelin & Ruddell, 2013), expand its notions of placefulness, and merge students’ on-course and beyond-course identities.

Primarily, an important re-conceptualization of “nature” is in order if humans are to more justly and more appropriately understand the more-than-human (Abrams, 1996) world around us. Typically, in outdoor education and beyond, environmentally conscious educators have focused on an objectification of the landscapes around us, particularly the seemingly pristine “wilderness” that is often the settings for outdoor education expeditions. Without denying the materiality of the landscapes in which outdoor education takes place, the meanings behind these landscapes are entirely human creations. From this perspective, nature is a highly subjective effect of power (through discourse), and neither nature nor society are separate or stable categories of being (Braun & Wainwright, 2001). Rather, nature (and also, society) is only the discursive meanings we place upon it. We cannot “know nature without acknowledging and critiquing the very real social, political, economic, and ecological histories that inform our popular contemporary notions of what nature means to each of us individually, as well as to our collective societies” (Rose, 2013). For outdoor education, this re-conceptualization means that we should see ourselves as community members of the more-than-human world around us, rather than as stewards of remote landscapes distant from our daily experience that should be treated differentially. “Working towards social justice from the perspective that humans are a part of nature rather than apart from nature lends both power and ecological integrity to the cause of justice and provides a solid foundation upon which to begin transformative work” (Cachelin, 2010, p. 200). This re-conceptualization is foundational to linking justice and sustainability to outdoor education.

Secondly, with this re-conceptualization in place, outdoor educators can effectively lead the charge to expand our students’ and our own concepts of placefulness (Tuan, 1980). While developing a sense of place has long been a goal of many outdoor education programs (Baker, 2005; Knapp, 2005), sense of place is also a construct that is difficult to apprehend or quantify, and subsequently, to research. Perhaps a helpful reconsideration here is for outdoor educators to employ the construct of “sheds.” A watershed, for instance, is not just a particular creek or water body, but the entire area of land that ultimately drains surface and sub-surface water into a particular creek or water body. Ecologists, then, are not interested solely in the health of a stream, but also in the health of the extensive landscapes that inform the stream’s health. Imagine an outdoor education experience where students begin to viscerally understand the various watersheds of which they are geographically and biophysically a part. At any spatial point, students might recognize that they are likely parts of many watersheds existing at different scales, the largest of which probably drains into a very distant body of water (an ocean or terminal inland lake, perhaps). This “shed” connects the immediately local landscapes and the immediately local experiences with other landscapes and other experiences that are likely relatively distant, bringing the faraway nearby by creating new understandings and bringing previously unrealized connections to light. Beyond watersheds, it might be productive for us to consider the various “sheds” of which we are a part: foodsheds, gearsheds, fuelsheds, and with our various human connections, socialsheds (i.e., communities) as well. Mapping these sheds provides a visual representation of the vast interconnections we share with the various living and non-living systems on this planet. This concept of “sheds” encourages us to understand that we are members of larger ecological communities, preparing students for heightened ways of perceiving the world and filtering experiences. Rather than feeling that our outdoor education experiences take place in some distant mountain range or far-off landscape, we can begin to see the various interconnections that exist between ourselves and our other human and more than human community members across the globe.

Lastly, outdoor education should work to decrease the metaphorical (and literal and geographic) distances between our courses and the rest of our lives. Outdoor education must consider ways to further merge students’ on-course identities with their post-course identities. This point has long been a fundamental critique of outdoor education, that long-term outcomes are either very minimal or completely unknown (Neill, 2002; Sibthorp et al., 2008; Wolfe & Samdahl, 2005). Outdoor education students’ on-course experiences should challenge, complicate, and complement their everyday experiences, and we should work to bridge epistemological and ontological gaps that exist between these experiences. These identities should not be separate, but should be self-reinforcing such that an experience backpacking with a group of teenagers in the mountains supports, re-focuses, challenges, and reinscribes everyday experiences as members of multiple communities and as active and engaged citizens.

A Contextualized Example

In outdoor education, the pedagogical and practical tool of Leave No Trace (LNT) has become a nearly ubiquitous curricular element. It has been incorporated into outdoor education programs for good reason, as its efficacy at curbing the immediate visual effects of human behavior in backcountry settings has been researched and documented extensively (Cole & Monz, 2004; Hammitt & Cole, 1998). However, LNT has also been extensively critiqued in this journal (Cachelin et al., 2011) and elsewhere on account of its limited geographic focus (Andre, 2012; Simon & Alagona, 2009), its ironic encouragement of consumptive lifestyles (Simon & Alagona, 2013), its impossibility to “leave no trace” even when following the programs principles (Simon & Alagona, 2013), and its inappropriateness as a pedagogical tool in outdoor education settings (Moskowitz & Ottey, 2006). These critiques note that LNT is only a productive practical and metaphorical tool when we limit the scale of analysis to the very immediately local landscapes. Cachelin et al (2011) point out that the message and pedagogy of LNT metaphorically position humans and human behavior as being diametrically opposed to a perceived unspoiled “nature” that surrounds us, presenting a confounding and highly problematic relationship between humans and the non-human world of which we are all a part (Cronon, 1996).

LNT is very successful when the scale of analysis is limited in scope, but it breaks down quickly when it is considered in light of multiple overlapping and intersecting landscapes. These landscapes extend beyond merely the physical or geographical, reaching into the political, social, cultural, and economic. In considering a small piece of litter on a backpacking trip, LNT advises us (wisely) to “pack it out.” If the scale of our analysis remains only the forest, the watershed area, or the land management parcel of our backpacking trip, then packing it out is more than reasonable. But, when the scale of analysis includes multiple landscapes, simply “packing it out” is not educationally responsible or ecologically valid. In fact, the “pack it out” mindset is very much in keeping with ideas that drive capitalist accumulation in that by focusing on just one localized piece of a system, we create social and environmental injustices if and when the scale of analysis extends beyond the immediately local. Given a global analysis, just as it is lucrative yet ethically bankrupt to export labor-intensive jobs and degrade distant landscapes, a piece of “litter” must be considered in light of its entire lifespan, and beyond. Where did it begin its existence, what impacts are inherent in its production and consumption, and where will it decompose, if it will decompose at all? These questions illustrate the landscapes of production and consumption, of waste and toxic by-products, of the unnamed “side effects” of our global relationships (Andre, 2012).

A much needed and more responsible perspective that should be brought into outdoor education settings is a perspective of vastly interconnected landscapes. These landscapes are the systems on which all life is based. A helpful perspective for understanding this landscape-focused construct is the (admittedly contested) notions of space and place. Spaces, in this context, are the objective, defined, boundaried, and discrete landscapes. Places, on the other hand, are spaces with the addition of meaning and experiences (Tuan, 1977). Space is what place becomes when the unique gathering of things, meanings, and values are removed (de Certeau, 1984; Harvey, 1996). Spaces are easily mapped, quantified, contained, and detached from material form and cultural interpretations, whereas places are those spaces that are imbued in our consciousnesses and in our cultures with memories, emotions, and, importantly, experiences. Importantly, places have a geographic location, material form, and human investment with meaning and value (Gieryn, 2000). Places are those subjective understandings of spaces, ones that vary across time, culture, and ecosystems. Simply put, places are spaces with the addition of human experiences. For instance, imagine the childhood memories of a backyard, neighborhood basketball games, playing along a creek, building forts, following tracks in the fresh snow, and the phenological observations of the changing seasons over the years. This place could also be understood as a space, noting the objective characteristics of the area that are void of memories, emotions, and sense of connection to the landscape. But without noting the experiences that come from human engagement with space, this landscape removes important relational understandings that we have with the world around us. Further, the ability to see, feel, and understand the interconnectedness of landscapes is left wanting. From a sustainability perspective, developing, maintaining, and nurturing a deep sense of place is vital for the understanding and appreciation of our interactions with the non-human worlds in which we live. And in many ways, this is what outdoor educators are best at, turning space into place by adding experience and helping students to generate personal meanings from their outdoor education experiences.

Outdoor education courses are particularly well-suited for students to increase their notions of placefulness (Baker, 2005, Knapp, 2005). Through intense, necessarily multisensory experiences, students become intimately connected to the spaces they encounter. Sense of place, a mosaic of sensory experiences over time, is facilitated through outdoor education experiences. Many seemingly inherent components of an outdoor education course immediately conjure notions of connecting place. Outdoor education often features seemingly intense experiences, meaningful social interactions, and visceral interactions and connections with the biophysical world around us. Consider, for example, some questions that commonly arise on a multi-day outdoor education backpacking course: Where will we find a source of water for drinking and cooking? Should we hike over this pass or down this drainage? How might changing tent groups or cook groups affect our group processes? Should I pack my rain gear near the top of my backpack today? What are the various advantages and disadvantages of hiking over talus, tundra, or using a trail? What are the possible consequences of not hanging our food in a tree tonight? These questions, whether posed directly or presented experientially of the course of an outdoor education experience, begin to foster the type of thinking that connects students to place. The question then becomes how can outdoor educators attend to changing space to place at different scales, which becomes particularly important when we consider that people are much more likely to care about, and consequently preserve, places than they are spaces (Graham & Healey, 1999).

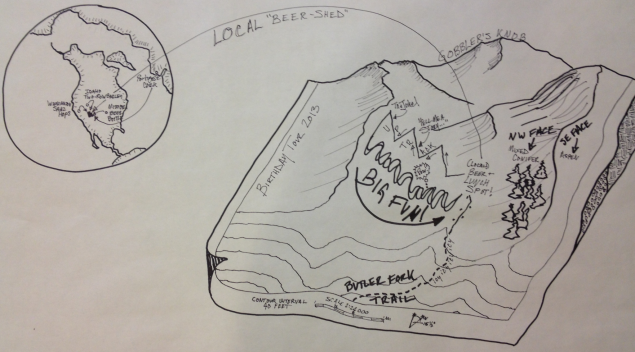

A technique that has potential for increasing students’ awareness of the intersecting and overlapping landscapes of which they are a part is place mapping. A brief, but thorough discussion of the basic differences between space and place (Gieryn, 2000; Tuan, 1977) is a helpful context for commencing, with students beginning to imagine the various spaces and places of their own lives. Place, with its seemingly infinite possibilities for meaning and understanding, differentiates itself from space with its layers, texture, and folds of complexity. When students are asked to make a map of the place where they are currently located, recent experiences can be combined with a lens of analysis that includes various systems that inform the immediately local. The tentacles of place necessarily reach beyond the geographically near and extend to distant landscapes when we consider systems of production, consumption, disposal of material items, and the social relationships that form and are formed by these processes. Place-based thinking also encourages the querying of social, political, economic, and technological systems that inform our experiences, memories, and relationships. Outdoor education courses typically introduce map and compass skills, which provide good introductions to understanding spatial features of the surrounding landscapes. Most recreational maps also introduce important place features, such as toponyms (Kadmon, 2000) or landscape names, map titles, symbols, historical events, trails, and land management designations. Often students are asked to create maps of their home places in order to build group dynamics and come to know each other better while being able to compare and contrast their everyday lives to the adventures in which they participate during outdoor education programs. As students make their own maps of the surrounding landscapes, they should be encouraged to incorporate and develop these subjective emotional meanings and experiences into their maps. Figure 1 (below) provides a singular example of one interpretation of the place mapping assignment, where a map was constructed to incorporate some of the features that might be included in a place map, as well as one that begins to include a jumping off point for discussions of critical sustainability. Experiences, emotions, inside jokes, and toponyms are included. This example is given to provide context for the way in which a map could look, not how a place map should look. The intense diversity of maps across a student population should be explored and celebrated, as students can subsequently incorporate more detail, data, and complexity into their own maps. Sharing the maps with a partner or with a group can provide an intense socially connecting experience.

Figure 1. An example of a place map for a recent backcountry ski tour. Included in the experience are local place names (toponyms), memories, and emotions, in addition to topography and other technical features of traditional maps. Further, the concept of near and far landscapes are incorporated into the production and consumption of beer on this ski tour.

Place maps have direct implications for the awareness and promotion of sustainability and social justice in an outdoor education context. Places, by definition, cannot exist on their own, instead requiring vast interconnections of personal relationships and experiences. Places are also generally important to the individual (or to a collective), which encourages an understanding of the potential for socioecological sustainability of that place. Considering a place’s future requires not just questioning the immediate surrounding landscapes of the place, but also of the near and far systems that influence it, raising immediately imperative questions concerning sustainability: How might the character of this place’s landscape change if I destroy a tree, dig a latrine, or inappropriately dispose of my trash? Is there an appropriate way to dispose of trash? What production and packaging techniques or consumer choices may help me avoid this dilemma? How did last season’s snowpack affect the quantity and quality of drinking water near our campsite? Why do there seem to be more marmots near this campsite this year than last year? What noises – human produced or otherwise – can I hear at any given moment? How will this place look in the future if society continues to burn fossil fuels at the current rate?

Questions of social justice are likely to also emerge from these sustainability-focused questions: How are my experiences in this place affected by the people with whom I am traveling? How do their off-course lifestyles support or undermine my connection(s) to this place? What social, political, and economic systems support me being here, in this place, and what systems limit others from connecting similarly to this place or other places? Basically, how can we examine our own privileges? How is my being here, on this outdoor education experience, perhaps perpetuating injustices in both near and far locations? If I pack this trash out, what responsibility do I have to see that its disposal is not degrading distant landscapes? Place mapping, as opposed to the more technically sophisticated space mapping, encourages critical questions that support students’ thinking well beyond the local, beyond outdoor education, and beyond the here and now. Place mapping combines the tangible connection to the immediate location while simultaneously supporting the abstraction of bringing together multiple social and spatial landscapes, requiring a critical orientation that is helpful in connection sustainability and social justice – critical sustainability – to outdoor education experiences. In the place map presented as our example, specific experiences (skiing, hiking, etc.) are placed into spatial and social relationships with local and global human and non-human communities. Social justice, per se, is not necessarily directly addressed, but place maps such as these support and enable both illustrators and viewers to think about possible critical questions concerning inequalities, injustices, and interrelationships between groups of people, between the various sociopolitical systems that help construct our experiences in the world, and between humans and the non-human world.

Place mapping techniques can contribute significantly to critical sustainability. We have suggested in this article that outdoor education should promote critical sustainability through the merging of identities, connecting humans with the non-human world around us, and embedding individuals within places. The map example represented here helps illustrate that an experience in the outdoors is intricately interconnected with larger circuits of the political economy, as well as with larger ecological systems. Such recognition helps merge our outdoor experiential identities with our everyday identities. Secondly, the map is a visual representation of some of our complex relationships with the non-human world of which we are a part. It helps illustrate the multiple, layered interconnections between our everyday experiences and the local and global reaches of our decisions and behaviors. Finally, the map shows that we are part of the place, potentially even part of multiple systems. Places, after all, have human components to them (Gieryn, 2000), and for a given moment in time, the space in question was intimately affected by the human experiences that took place there. Maps such as these can help identify elements of critical sustainability, particularly that there is no environmentally sustainable behavior that does not include socially, politically, and economically just relations, and that these factors, while often treated as separate, are intimately interconnected and co-dependent.

This mapping technique is not without its limitations. The type of mapping described here can be very difficult for people to imagine, and may work best when introduced as a progression, or a series of activities, rather than as a singular experience. Mapping by itself will not inherently contribute to our notion of critical sustainability. Rather, mapping is one of many constructivist pedagogical experiences that might help frame conversations and lessons centered upon critical sustainability. Finally, we recognize that our own positionalities contribute to our advocacy for this technique: experiential educators who have had positive interactions with students engaging in outdoor settings. Clearly this activity should be adjusted for subjective student factors, local environmental conditions, and other requisite subjectivities.

Conclusions

Critical sustainability, connecting sociopolitical systems of oppression and privilege with the socioecological imperatives of supporting the future of the planet and all of its living and non-living systems, represents a necessary path forward for educators. And this direction for progress is fraught with epistemological and reflexive challenges. For instance, what understandings of the world in which we live are necessary to support and ensure its survival? Further, what personal practices and political orientations are currently undermining a justice-oriented framework? How do we engender relationships with species that reimagine or enact a non-dominant positionality? Evans (2010) suggests that various educational systems (intentionally) shy away from addressing critical, social justice-oriented curricula and discourses, to their own detriment and to the detriment of the world at large. One of the reasons in which we tend to avoid such pedagogical moments is because we ourselves are implicated in the systems that are currently under critique. None of us are immune from critical analysis; some of our own privileges and comforts will necessarily be curtailed if we are to move closer toward social justice and sustainability.

Outdoor education is one of many settings in which critical sustainability concepts must be implemented, explored, critiqued, contextualized, and expanded. Pedagogically, mapping the places that are so meaningful and important to us provides an experiential learning mechanism that begins to explore our surrounding social and ecological landscapes. The process is valuable, in part, because students come to their own conclusions and own contextualized understandings of their unique circumstances as members of the more-than-human world. Educators have a responsibility to facilitate these processes, to provide support and foundational information, and to help students develop their own critical analyses of the world around them. Because of the intensely visceral nature of the experience, outdoor education is particularly well suited to advance critical sustainability in the field during the experience itself. Further, outdoor education has traditionally operated as a vehicle for transference of knowledge (Priest & Gass, 2005), promoting further reasoning and action on issues of critical sustainability beyond the time in which the course takes place. In this light, the institution of outdoor education – like each of us – needs to realize the problems existing within, as well as the potential for moving well beyond.

References

Abrams, D. (1996). The spell of the sensuous. New York, NY: Vintage books.

Adams, W.M. (2006). The future of sustainability: Re-thinking environment and development in the twenty-first century. In Proceedings of the IUCN Renowned Thinkers Meeting. Gland, Switzerland.

Andre, E. (2012). It’s time for a global ethic; not just local etiquette. In M. Wagstaff and B. Martin (Eds.), Controversial issues in adventure programming (248-254). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

Baker, M. (2005). Landfullness in adventure-based programming: Promoting reconnection to the land. Journal of Experiential Education, 27(3), 267-276.

Barrett, G.W., & Odum., E.P. (2000). The twenty-first century: The world at carrying capacity. BioScience, 50(4), 363-368.

Bowdridge, M., & Blenkinsop, S. (2011). Michel Foucault goes outside: Discipline and control in the practice of outdoor education. Journal of Experiential Education, 34(2), 149–163.

Braun, B. & Wainwright, J. (2001). Nature, poststructuralism, and politics. In N. Castree & B. Braun (Eds.) Social nature: Theory, practice, and politics (pp. 41-63). Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Brown, M. (2002). The facilitator as gatekeeper: A critical analysis of social order in facilitation sessions. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 2(2), 101–112.

Buell, F. (2003). From apocalypse to way of life: Environmental crisis in the American century. New York, NY: Routledge.

Cachelin, A., & Ruddell, E. (2013). The impact of language framing on sustainability education. Journal for Environmental Studies and Sciences. DOI 10.1007/s13412-013-0131-2.

Cachelin, A. (2010). What lies beyond social and environmental justice? An ecological narrative. In K. Paisley and D. Dustin (Eds.), Speaking up and speaking out: Working for social and environmental justice through parks, recreation, and leisure (pp. 193-200). Champaign, IL: Sagamore.

Cachelin, A., Paisley, K., & Dustin, D. (2009).Obligation and opportunity: A role for outdoor educators in the sustainability revolution. Journal of Outdoor Recreation, Education, & Leadership, 1(2), 141-150.

Cachelin, A., Rose, J., Dustin, D, & Shooter, W. (2011). Sustainability in outdoor education: Rethinking root metaphors. Journal of Sustainability Education, 2(March).

Cole, D., & Monz, C. (2004). Spatial patterns of recreation impact on experimental campsites. Journal of Environmental Management. 70, 73-84.

Cronon, W. (1983). Changes in the land: Indians, colonists, and the ecology of New England. New York, NY: Hill & Wang.

Cronon, W. (1996). The trouble with wilderness. In W. Cronon (Ed.) Uncommon ground: Rethinking the human place in nature (pp. 69-96). New York, NY: W.W. Norton.

Curran, M.A. (2009). Wrapping our brains around sustainability. Sustainability, 1(1), 5-13.

Davis, M. (2004). Planet of slums: Urban involution and the informal proletariat. New Left Review, 26(March-April), 5-34.

Davis, M. (2006). Planet of slums. New York, NY: Verso.

de Certeau, M. (1984). The practice of everyday life. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Denzin, N., & Lincoln, Y. (2013). Introduction: The discipline and practice of qualitative research. In N. Denzin and Y. Lincoln (Eds.), The landscape of qualitative research (pp. 1-41, 4th Edition). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Di Chiro, G. (1996). Nature as community: The convergence of environment and social justice. In W. Cronon (Ed.), Uncommon ground: Rethinking the human place in nature (pp. 298-320). New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company.

Dietz, S., & Neumayer, E. (2007). Weak and strong sustainability in the SEEA: Concepts and measurement. Ecological Economics, 61(4), 617-626.

Dowie, M. (2009). Human nature. Guernica: A magazine of art & politics. Retrieved 20 December 2012 from http://www.guernicamag.com/features/human_nature/.

Duxbury, G. (2004). Sustainable communities: Regeneration and a just society. In J. Foley (Ed.), Sustainability and social justice (pp. 13-23). London, UK: Institute for Public Policy Research.

Elkington, J. (1997). Cannibals with forks: The triple bottom line of 21st century business. Oxford, UK: Capstone Publishing.

Exner, A., Fleissner, P., Kranzl, L., & Zittel, W. (Eds.) (2013). Land and resource scarcity: Capitalism, struggle and well-being in a world without fossil fuels. New York, NY: Routledge.

Evans, T. (2010). Critical social theory and sustainability education at the college level: Why it’s critical to be critical. Journal of Sustainability Education, 2.

Evans, T. (2011). Leadership without domination? Toward restoring the human and natural world. Journal of Sustainability Education, 2.

Fisk, P. (2010). People, planet, profit: How to embrace sustainability for innovation and business growth. London, UK: Kogan Page Limited.

Foley, J. (2004). Overview. In J. Foley (Ed.), Sustainability and social justice (pp. 1-12). London, UK: Institute for Public Policy Research.

Furman, N., & Sibthorp, J. (2011). The transfer of expedition behavior skills from the National Outdoor Leadership School to life post-course. Journal of Outdoor Recreation, Education, and Leadership, 3(2), 87-90.

Gieryn, T. (2000). A space for place in sociology. Annual Review of Sociology, 26, 463-496.

Graham, S., & Healey, P. (1999). Relational concepts of space and place: Issues for planning theory and practice. European Planning Studies, 7(5), 623-646.

Hammitt, W., & Cole, D. (1998). Wildland recreation: Ecology and management. New York, NY: John Wiley.

Hartnett, S. (1998). Lincoln and Douglas meet the abolitionist David Walker as prisoners debate slavery: Empowering education, applied communication, and social justice. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 26(2), 232-253.

Harvey, D. (1996). Justice, nature and the geography of difference. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell.

Harvey, D. (2009). Social justice and the city. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press.

Hoag, D.L., & Skold, M.D. (1996). The relationship between conservation and sustainability. Journal of Soil and Water Conservation, 51(4), 292-295.

Holifield, R. (2012). Environmental justice as recognition and participation in risk assessment: Negotiating and translating health risk at a superfund site in Indian Country. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 102(3), 591-613.

Hunt, J. (1994). Ethical issues in experiential education (2nd ed.). Boulder, CO: The Association for Experiential Education.

Kadmon, N. (2000). Toponymy: The lore, laws and language of geographical names. New York, NY: Vantage Press.

Kates, R. (1987). The human environment: The road not taken, the road still beckoning. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 77(4), 525-534.

Kay, J. (1989). Human domino over nature in the Hebrew Bible. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 79(2), 214-232.

Knapp, C. (2005). The “I – Thou” relationship, place-based education and Aldo Leopold. Journal of Experiential Education, 27(3), 277-285.

Ladson-Billings, G. & Donnor, J. (2008). The moral activist role of critical race theory scholarship. In N. Denzin & Y. Lincoln. (Eds.), The landscape of qualitative research (3rd ed., pp. 371-401). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Li, M. (2008). The rise of China and the demise of the capitalist world-economy. London: Pluto Books.

Li, M. (2010). The end of “the end of history”: The structural crisis of capitalism and the fate of humanity. Science & Society, 74(3), 290-304.

Liu, L. (2009). Sustainability: Living within one’s own ecological means. Sustainability, 1, 1412-1430.

Losada, H., Vieyra, J., Soriano, R., Bennett, R., & Cortes, J. (2001). Assessing the sustainability of a terraced agroecosystem for production of maple vegetable in metropolitan Mexico City. American Journal of Alternative Agriculture, 16(3), 98-105.

Mann, C. (2005). 1491: New revelations of the Americas before Columbus. New York, NY: Knopf.

Martin, P. (1999). Critical outdoor education. In J. P. Miles & S. Priest (Eds.), Adventure education (2nd ed., pp. 463–471). State College, PA: Venture.

Moskowitz, D., & Ottey, D. (2006). Leaving LNT behind: Towards a holistic land use ethic. Green Teacher, 78(Spring).

Nagda, B., Gurin, P., & Lopez, G. (2003). Transformative pedagogy for democracy and social justice. Race Ethnicity and Education, 6(2), 165–191.

Neill, J. (2002). Meta-Analytic Research on the Outcomes of Outdoor Education. Paper presented at the Coalition for Education in the Outdoors Sixth Biennial Research Symposium. Bradford Woods, Indiana.

Pattison, W. (1990). The four traditions of geography. Journal of Geography, September/October, 202-206.

Priest, S., & Gass, M. A. (2005). Effective leadership in adventure programming (2nd ed.). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

Rasul, G., & Thapa, G. (2004). Sustainability of ecological and conventional agricultural systems in Bangladesh: An assessment based on environmental, economic and social perspectives. Agricultural Systems, 79(3), 327-351.

Rawson, M. (2010). Eden on the Charles: The making of Boston. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Rose, J. (2013). Contesting homelessness: Public nature, political ecology, and socioenvironmental justice. In K. Schwab and D. Dustin (Eds.), Just leisure (pp. 58-66). Champaign, IL: Sagamore.

Rose, J., & Paisley, K. (2012). White privilege in experiential education: A critical reflection. Leisure Sciences, 34(2), 136-154.

Rosen, M.A. (2009a). Sustainability: A crucial quest for humanity. Sustainability, 1(1), 1-4.

Rosen, M.A. (2009b). Energy sustainability: A pragmatic approach and illustrations. Sustainability, 1(1), 55-80.

Sherman, D. (2008). Sustainability: What’s the big idea? Sustainability: The Journal of Record, 1(3), 188-195.

Sibthorp, J., Paisley, K., Furman, N., & Gookin, J. (2008). Long-term impacts attributed to participation in adventure education: Preliminary findings from NOLS. Research in Outdoor Education, 9, 86-102.

Simon, G., & Alagona,P. (2009). Beyond Leave No Trace. Ethics, place and environment, 12(1), 17-34.

Simon, G., & Alagona, P. (2013). Contradictions at the confluence of commerce, consuption and conservation; or, an REI shopper camps in the forest, does anyone notice? Geoforum, 45(1), 325-336.

Tuan, Y.F. (1977). Space and place: The perspective of experience. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Tuan, Y.F. (1980). Rootedness versus sense of place. Landscape, 24, 3-7.

Wainwright, J., & Mann, G. (2013). Climate leviathan. Antipode, 45(1), 1-22.

Warren, K. (2005). A path worth taking: The development of social justice in outdoor experiential education. Equity & Excellence in Education, 38, 89–99.

White, L. (1967). The historical roots of our ecological crisis. Science, 155, 1203-1207.

Williams, C. (2010). Ecology and socialism: Solutions to capitalist ecological crisis. Chicago, IL: Haymarket.

Williams, C.C., & Millington, A.C. (2004). The diverse and contested meanings of sustainable development. The Geographical Journal, 170(2), 99-104.

Wolfe, B., & Samdahl, D. (2005). Challenging assumptions: Examining fundamental beliefs that shape challenge course programming and research. Journal of Experiential Education, 28(1), 25-43.

Zimmerer, K. (2000). The reworking of conservation geographies: Nonequilibrium landscapes and nature-society hybrids. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 90(2), 356-369.

Zimmerer, K. (2010). Retrospective on nature-society geography: Tracing trajectories (1911-2010) and reflecting on translations. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 100(5), 1076-1094.

Jeff Rose, Ph.D., is an Assistant Professor/Lecturer in the Department of Parks, Recreation, and Tourism and affiliate faculty with the Global Change and Sustainability Center at the University of Utah. As a political ecologist, his research interests concern public space, productions of nature, connection to place, and various non-normative behaviors.

Jeff Rose, Ph.D., is an Assistant Professor/Lecturer in the Department of Parks, Recreation, and Tourism and affiliate faculty with the Global Change and Sustainability Center at the University of Utah. As a political ecologist, his research interests concern public space, productions of nature, connection to place, and various non-normative behaviors.  Adrienne Cachelin, Ph.D., is an Associate Professor in the Environmental and Sustainability Studies program. She currently serves as the Education Director for the University’s Sustainability Office and the Associate Director of the University’s Global Change and Sustainability Center. Her research interests include environmental justice, food justice, and conceptions of health and sustainability.

Adrienne Cachelin, Ph.D., is an Associate Professor in the Environmental and Sustainability Studies program. She currently serves as the Education Director for the University’s Sustainability Office and the Associate Director of the University’s Global Change and Sustainability Center. Her research interests include environmental justice, food justice, and conceptions of health and sustainability.