Hope and a hike: Cultivating nature connection and hope and setting the stage for action through a women’s walking group

Dyer JSE Fall 2017 General PDF

LINK: December 2017 General Issue: Curriculum and Change Table of Contents

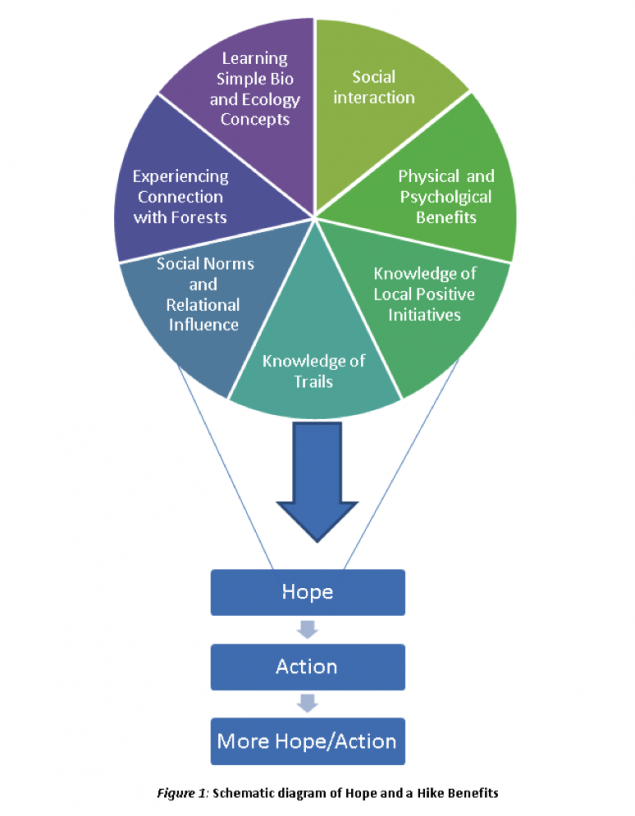

In 2014 I began “Hope and a Hike” a weekly Meetup intended to combine exercise, health gains and social opportunity with knowledge, positive local conservation success stories and experience in forested areas, as a community action project for my Master’s program. The experience was so positive I have continued it for the past three years. This article shares a combination of observations gathered since the beginning of Hike and a Hope. Some feedback from participants was collected as part of my work as a student; some was collected independently of my studies. The goal is to awaken a connection to the natural environment with hope and a desire to care and take action for the environment in some of these women (Fig.1).

On a breezy Sunday afternoon, a dozen women emerge from their vehicles – the first timers hesitantly approaching to join the group of women in the parking lot. These women each clicked “yes” to an invite for this week’s one-hour event through Meetup.com. Names are exchanged yet again as a few more walkers arrive and each person hands me a dollar to contribute to the cost of having a Meetup site online. We hear some crows call from atop the spruce trees–sentinels at the edge of the forest. We are not all Southeast Michigan natives, but some of us yearn for reconnection with the land, with our bodies through movement, and with a world that feels whole and moving forward. I inhale, hoping that I’m offering that kind of gift with this Meetup group.

When everyone arrives, we dive into the hope topic for today’s hike. Most of the women are new to the group or have never been to this forest on the edge of Ann Arbor, Michigan so I pull out maps of the watershed and the green belt properties around the city. I locate this nature area and talk about how farm properties and small forests are being preserved, parcels becoming a patchwork corridor. One reason I chose this topic is that research shows that people who participate in activities such as hiking and nature study are more likely to place their land in a conservation easement than those who participate in activities such as hunting and fishing (Ramesh, Gary, Neelam & Ken, 2014). The hope topics that the women’s group learn about range from the osprey and eagle rebounds in Michigan, to the end of the sale of nicotinoids in local stores, to citizen science monitoring and vernal pool mapping. Defining hope and sharing hopeful quotes was yet another of the many topics on the more than 90 hikes I have led with this group over the past three years (Appendix A). This sharing illustrates a variety of innovative ways individuals and groups are doing something positive for the well-being of ecosystems members now and in the future.

The Gift of Hope

The very least you can do in your life is figure out what you hope for. And the most you can do is live inside that hope. Not admire it from a distance but live right in it, under its roof. — Barbara Kingsolver, Animal Dreams

Sharing stories of hope offsets the doom and gloom in the news (Kelsey & Armstrong, 2012). It is a step toward cultivating constructive hope. Research shows that constructive hope is positively related to pro-environmental behaviors (Ojala, 2012). Ojala found that constructive hope comes from a change of perspective: reframing issues more positively in difficult situations to avoid being overwhelmed, trusting in outside resources (such as technology), and seeing oneself as a positive agent of change. This goes far beyond the idea of hope as just optimistically wishing for change. Ojala also found that when individuals believe that ordinary citizens working together can have an impact, they engage in more private behavior change. I am building on Solnit’s (2016) call to action to share examples of positive change and to remind people of what we have accomplished (pp. xx-xxi) as well as Macy and Johnstone’s (2012) “active hope”. I do this by introducing the realities in forested places, the good and the bad, and then sharing ways that individuals and groups are taking action locally, while inviting them to participate in some of the actions. Furthermore, I am working toward Freire’s (1994) idea that to overcome despair we need education in hope; how taking action feeds hope and hope feeds taking action (p.9). Educators in university have developed in-depth programs to foster active hope (See JSE issue on hope, Evans, 2015), but small steps can be taken in setting such as Meetups. I am aware that it is less likely that the women attending today were more motivated by hope than by the call of exercise, a social opportunity, or a chance to explore a new outdoor place, however hope can be awakened. It is likely that the women who attend “Hike and a Hope” have been more motivated by the call of exercise, a social opportunity, or a chance to explore a new outdoor place, than by hope, however hope can be awakened.

The Gifts of Women’s Perspectives

Education, if it means anything, should not take people away from the land, but instill in them even more respect for it, because educated people are in a position to understand what is being lost. The future of the planet concerns all of us, and all of us should do what we can to protect it. As I told the foresters, and the women, you don’t need a diploma to plant a tree. — Wangari Maathai

I started the group with a focus on women because women show more concern for environmental problems, and see them as more serious than men do (McCright, 2010). Women have more developed empathy that leads to more environmental concern and action (Arnoky & Stroink, 2010). Women also tend to have stronger environmental attitudes (Gardos & Dodd, 1995; Zelezny, Poh-Pheng & Aldrich, 2000) and more pro-environmental behaviors probably because they are socialized to be more concerned about others and more socially responsible (Hallum-Montes, 2012; Zelezny et al., 2000). Women are also less likely to accept current systems/ways of doing things as acceptable when serious environmental challenges arise (Goldsmith, Feygina & Jost, 2013). Therefore, as a group, women often have different emotional and social attributes than men concerning

environmental behaviors.

I also specifically chose women because they may hold a unique position to continue to take on environmental action in challenging times. Researchers who looked at climate change action found that place attachment, receiving a message about the impacts of climate change locally, and gender (female) were significant (Scannell & Gifford, 2013). Women are especially important in certain environmental efforts because they make changes in their environmental behavior at the personal level more than men do (Hunter, Hatch & Johnson, 2004; Semenza, 2011; Xiao & McCright, 2014). In addition, women see problems and conditions in the environment as less attributable to a higher power, government or chance, and view personal actions as necessary for change more often than men (Kalamas, Cleveland, & Laroche 2014).

“Hope and a Hike” attracts women from a variety of backgrounds and fields from marketing and education to medicine and travel. Some hail from Spain, China and India, and they chat with others from the East Coast or the South, yet all now find their feet walking the ground between the Great Lakes. I realize that as we recognize more gender possibilities (LGBTQIA+), a women’s group is problematic, but the studies mentioned do show reasons for creating a space specifically for women. To address this, I have contacted a local community education center to develop inclusive language for the group website so that anyone who identifies as a woman feels welcome to participate.

The Gifts of Walking in Forests

Going to the woods is going home.

— John Muir

Only some participants realize that walking in a forest area, in particular, has so many physical, cognitive, affective and restorative benefits (Berman, Jonides, & Kaplan, 2008; Carpenter, 2013; Hayes & Berman; 2015; Kuo, 2015; Li, 2010; Marselle, Irvine, & Warber, 2013; Roberson & Badic, 2009). Like some other women, they may find outdoor exercise more satisfying than indoor exercise (Plante et al., 2007). They may use walking as their main source of physical activity (Bryan & Katzmarzyk, 2009). Yet they may not walk in forested areas (Zanon, Doucouliagos, Hall, & Lockstone-Binney, 2013). Our hikes usually pass a stream, pond or the Huron River. Including a body of water in a nature experience gives extra health benefits in the form of improved self-esteem and mood (Barton & Pretty, 2010). On today’s hike, Third Sister Lake will appear in the middle of the forest to unsuspecting eyes.

In addition to the general physical and mental health benefits, walking groups, such as this one, may be important for addressing women’s safety concerns in parks (Foster, Hillsdon & Thorogood, 2004) and for getting more women active in parks (Cohen et al. 2016). Many of the women in the group say they have never been to most of the fifteen parks we have hiked even though some live within walking distance of one. They also express gratitude for having short organized hikes because they were afraid of getting lost, or for their safety, if they were to try it on their own.

Having experiences in nature can be an important component for developing motivation for conservation action. Palmberg and Kuru (2000) found that experience in nature increased willingness to participate in further outdoor activities and that it helped people develop empathy for nature. People who have experience with nature, e.g. activities in nature, with environmental activism, or even a natural catastrophe, are more likely to take action on environmental issues (Finger, 1994; Schultz, 2000). Our experiences in forests through “Hope and a Hike” might lead to more sustainable behavior.

The Gift of Awe

The most beautiful thing we can experience is the mysterious. It is the source of all true art and all science. He [sic] to whom this emotion is a stranger, who can no longer pause to wonder and stand in rapt awe, is as good as dead: his [sic] eyes are closed. — Albert Einstein

Now as we enter Saginaw Forest, the contrast between avoiding traffic at the park’s edge, and standing under the towering dark green of hundreds of century-old spruce trees brings some immediate exclamations of awe. “I had no idea this was here!” cried a first-timer. The feeling still hits me even after dozens of visits here. Providing opportunities for awe is important for promoting pro-environmental actions (Frantz & Mayer, 2014). Adults crave a sensory connection with the natural world (Wilson, 1984). Seeing the beauty in nature increases pro-social actions such as empathy and generosity (Zhang, Piff, Iyer, Kolvena & Keltner, 2013).

Experiencing awe can increase generosity, ethical decision- making and less focus on the individual self (Piff, Dietze, Feinberg, Stancato & Keltner, 2015). Feeling more connectedness to nature (including a sense of being part of something bigger, and an emotional closeness) predicts pro-environmental actions (Frantz & Mayer, 2014).

Gazing up among the trees, I have the hikers estimate the trees’ age and then let them ponder the answer during the five-minute walk down the trail to a worn sign that says “White Pine, 1906”. Our wide-eyed appreciation for the trees switches over to amazing people of the past as I reveal the story of the words. University of Michigan students of the early 1900’s carried tools on the street car and then walked a mile each direction for years to plant forty species on these eighty acres. The students and teachers had a dream of reviving the old worn out agricultural land of Southeast Michigan. We receive the gift of their vision and their labor. It’s not an old growth forest we are experiencing, but it still has restorative inspirational power.

The Gift of Knowledge

Those who contemplate the beauty of the earth find reserves of strength that will endure as long as life lasts. There is something infinitely healing in the repeated refrains of nature—the assurance that dawn comes after night, and spring after winter.

— Rachel Carson

As we round a bend, a highly eroded stream trickles by in a gully — an opportunity for a knowledge stop. Usually, here someone asks why it is so eroded. I stop the women for a brief look. They see firsthand the result of land left treeless by farming long ago and of runoff from land just upstream now built and paved for a small industrial park nearby. I point out the exposed roots and invasive plants, and sometimes mention my rain garden that captures storm water at my home. “I never noticed that before!” is a common comment. Then it’s back to walking. My goal is to make three to four quick stops. It would be easy to stop more frequently, but I know they want to walk foremost. (For a sample list of quick eco topics we have explored on past hikes, see Appendix B.) I pick a prominent easy-to-identify tree such as shagbark, white pine or black cherry to start developing “forest eyes.” Like learning a new language, when the words of a native speaker seem like just a blur of sound, we need a few basics to work with — in this case, to hone-in on points within the sea of bark and leaves. Here they have a beginning focused, sensory experience (Hauk et al., 2015), another kind of knowledge.

Moving downhill we suddenly come upon a quaint, historic, stone care-taker house and a small lake. For first-timers especially if they grew up in the area, surprise and awe typically emerge again. The urge to go to the edge of the water doesn’t die after childhood; it just slows its pace. So we go to have a quick look through a small lawn area and a fire pit where university students have worked and celebrated for over a hundred years. Sharing about people past and present, we connect with others who have cared for this place.

I save the sobering underground story of this place for the next stop. Just before the boardwalk I point out a small blue flag on a metal ground cap which is a monitoring site, one of many in the preserve, to check dioxane levels in the aquifer deep below us. The chemical contamination plume from production of industrial filters from the 1960s-80s now extends under our city and threatens the Huron River and possibly even our water supply. The stone house’s well and the lake are contaminated too. Some hear about this issue for the first time. Others knew, but feel the visceral sensation of being so near the factory and an affected natural area. It’s not a hope experience, but a spur to care following the awe. “I’m going to find out more about this and what we can do about it,” says one woman. The next time this environmental issue is in the news they may listen more closely and talk to someone about what to do.

As we follow the trail back toward the trailhead, I show the route we took on one of the highlighted maps I have uploaded to the Meetup so that they are more likely to return on their own. Some women have returned to hike sites, and told us about experiences at parks with their friends, children or grandchildren.

The Gift of Relational Activism

Do not wait for leaders; do it alone, person to person.

— Mother Teresa

During the hikes, I also practice ‘relational activism’. Relational activism contributes to changes in communities and personal practices by using intentional modeling of daily environmental behaviors while building on relationships in the private sphere, or by taking actions that support others in conventional activism (O’Shaughnessy & Kennedy, 2010). On the hikes this is happening in many ways: when I talk about my experiences with family in the forest and volunteering at clean-ups or citizen science events, and when I make an effort to show my feelings for a place. Other examples of relational activism include offering a canning workshop and dinner, bike repair advice on the front porch, connecting experts with a friend in local government, providing childcare for others to work on political action, and showing friends, family and acquaintances their own sustainable home changes. Relational activism builds on the power of example and of relationship over time (O’Shaughnessy & Kennedy, 2010).

I’ve also done a few special relational hikes. One of them included a tour of my rain gardens, and another was a special walk to the city’s water source where we collected water and carried it so that we might physically connect with women who carry water daily to meet their essential needs. That special event ended with members at stations exploring water issues in the Great Lakes. Reactions included, “I hadn’t thought about where my water comes from, where it gets cleaned or where it goes.” and “The experience of carrying water for miles made me think about how I take my tap for granted.” They took home ways to get involved, at home or as a volunteer with organizations that I have participated in. At these social events women hear about and observe how someone like them is taking actions.

Gifts in the Future

A man’s [sic] value to the community primarily depends on how far his [sic] feelings, thoughts and actions are directed towards promoting the good of his [sic] fellows. –Albert Einstein

In the future, I plan to expand activities further by having a hope speaker at a hike. She was part of a group of citizens that organized to save a local forest from development and make it a park. This year I will also invite members to a stewardship day at one of the parks. As the group continues, I want to reach out to more women who are members of minority ethnic groups in the area. I will also try ending hikes with a suggestion to think about gratitude for something that inspired them on the day’s hike, and I hope to add an evaluation form to the Meetup site in addition to the existing option to write a review. Ideally, group members themselves may be able to expand some hikes by leading hikes, creating maps, or sharing hope topics.

I hope the women who participate in “Hope and a Hike” can become like the forests’ salamanders whose gift it is to cycle nutrients from the pond ecosystem to the forest ecosystem. These women, fed by their connection with the local forests, may carry knowledge and enthusiasm to motivate others to come and connect. We know that people who experience awe tend to act to share it with others (Piff et al., 2015). They may find their way to be a part of caring and giving back. If we wish to shift from a detached view of nature to a more holistic view, and we want more participation in sustainability actions, we need adults, as well as children and university students, to connect and feel hope. As we leave the forest someone says, “I would never have come on my own, and if I had I wouldn’t have seen the history and the effort people put into saving this place.”

Considerations for Starting Your Own Group

I tested out weekday vs. weekend hikes and found Sunday afternoon to work best for the largest number of people. However, the need to assess conditions for safety such as mud or ice make it difficult to schedule a location more than a few days ahead. Keeping the walk to one hour and the drive time for participants in town to about 20-25 minutes (some do come from farther away) is a reasonable time commitment. I also created rough home-made videos for two of the parks to give them more environmental information to access on their own (Dyer, 2016, link).

References

Arnocky, S., & Stroink, M. (2011). Gender differences in environmentalism: The mediating role of emotional empathy. Current Research in Social Psychology, 16(5), 1.

Barton, J., & Pretty, J. (2010). What is the best dose of nature and green exercise for improving mental health? A multi-study analysis. Environmental Science & Technology, 44(10), 3947-3955.

Berman, M. G., Jonides, J., & Kaplan, S. (2008). The cognitive benefits of interacting with nature. Psychological Science, 19(12), 1207–1212. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02225.x

Bryan, S. N., & Katzmarzyk, P. T. (2009). Patterns and trends in walking behaviour among Canadian adults. Canadian Journal of Public Health = Revue Canadienne De Santé Publique, 100(4), 294–298.

Carpenter, M. (2013). From “healthful exercise” to “nature on prescription”: The politics of urban green spaces and walking for health. Landscape and Urban Planning. Retrieved from http://proxy.lib.miamioh.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edselc&AN=edselc.2-52.0-84875178063&site=eds-live

Cohen, D. A., Han, B., Nagel, C. J., Harnik, P., McKenzie, T. L., Evenson, K. R., & … Katta, S. (2016). The first national study of neighborhood parks: Implications for physical activity. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 51(4), 419-426. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2016.03.021

Dyer, C. (2016, April 25). Miller Park in Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA (HD). Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_fbLnTvuuVI

Evans, T. (Ed.) (2015). Hope and Agency as Ontological Imperatives for Sustainability Education: An Introduction to the Special Issue of the Journal of Sustainability Education Focused on Hope and Agency. Journal of Sustainability Education.

Finger, M. (1994). From knowledge to action? Exploring the relationships between environmental experiences, learning, and behavior. Journal of Social Issues, 50(3), 141–160.

Foster, C., Hillsdon, M., & Thorogood, M. (2004). Environmental perceptions and walking in English adults. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 58(11), 924–928.

Frantz, C., & Mayer, F. (2014). The importance of connection to nature in assessing environmental education programs. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 4185-89. doi:10.1016/j.stueduc.2013.10.001

Freire, P. (1994). “Without a minimum of hope” Pedagogy of hope: Reliving pedagogy of the oppressed (p. 9). New York: Continuum Books.

Gardos V., & Dodd D. (1995, December 2). An immediate response to environmentally disturbing news and the environmental attitudes of college students. Psychological Reports, 77(3):1121. Retrieved from http://www.amsciepub.com.proxy.lib.miamioh.edu/doi/pdf/10.2466/pr0.1995.77.3f.1121

Goldsmith, R., Feygina, I., & Jost, J. (2013). The gender gap in environmental attitudes: A system justification perspective. In M. Alston & K. Whittenbury (Eds.), Research, action and policy: Addressing the gendered impacts of climate change (159-171). Netherlands: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-5518-5_12

Hallum-Montes, R. (2012). “Para el bien común” indigenous women’s environmental activism and community care work in Guatemala. Race, Gender & Class, 19(1/2), 104-130.

Hauk M., Baker, E., Cekani, R., Goyner, K., Green, C., Hale, K., … Zimdars, M. (2015). Senses of wonder in sustainability education, for hope and sustainability agency. Journal of Sustainability Education, 10.

Hayes, D., & Berman, M. (2015). Nature and the environment: The psychology of its benefits and its protection. Frontiers in Psychology, 6(NOV), doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01804

Hunter, L. M., Hatch, A., & Johnson, A. (2004). Cross-national gender variation in environmental behaviors. Social Science Quarterly (Wiley-Blackwell), 85(3), 677-694. doi:10.1111/j.0038-4941.2004.00239

Kalamas, M., Cleveland, M., & Laroche, M. (2014). Pro-environmental behaviors for thee but not for me: Green giants, green gods, and external environmental locus of control. Journal of Business Research, 67(2), 12-22.

Kelsey, E. and Armstrong, C. (2012). Finding hope in a world of environmental catastrophe. In A. Wals and P.B. Corcoran (Eds.) Learning for Sustainability in Times of Accelerating Change. Wageningen Academic Publishers’ Education and Sustainable Development Series, NL. http://www.elinkelseyandcompany.com/yahoo_site_admin/assets/docs/Kelsey_and_Armstrong_Hope.160131815.pdf

Kuo, M. (2015). How might contact with nature promote human health? Promising mechanisms and a possible central pathway. Frontiers in Psychology, 6

Li, Q. (2010). Effect of forest bathing trips on human immune function. Environmental Health and Preventive Medicine, 15(1), 9–17. http://doi.org/10.1007/s12199-008-0068-3 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2793341/

Macy, J. &Johnstone, C. (2012). Active hope: How to face the mess we’re in without going crazy. : Novato, CA: New World Library.

Marselle, M. R., Irvine, K. N., & Warber, S. L. (2013). Walking for well-being: Are group walks in certain types of natural environments better for well-being than group walks in urban environments? International Journal of Environmental Research & Public Health, 10(11), 5603–5628.

McCright, A. (2010). The effects of gender on climate change knowledge and concern in the American public. Population and Environment, 32(1), 66-87.

Ojala, M. (2012). Hope and climate change: the importance of hope for environmental engagement among young people. Environmental Education Research, 18(5), 625–642.

O’Shaughnessy, S., & Kennedy, E. H. (2010). Relational activism: reimagining women’s environmental work as cultural change. Canadian Journal of Sociology, 35(4), 551-572.

Palmberg, I. E., & Kuru, J. (2000). Outdoor activities as a basis for environmental responsibility. Journal of Environmental Education, 31(4), 32.

Piff, P. K., Dietze, P., Feinberg, M., Stancato, D. M., & Keltner, D. (2015). Awe, the small self, and prosocial behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 108(6), 883-899. doi:10.1037/pspi000001

Plante, T. G., Gores, C., Breeht, C., Carrow, J., Imhs, A., & Willemsen, E. (2007). Does exercise environment enhance the psychological benefits of exercise for women? International Journal of Stress Management, 14(1), 88–98.

Ramesh, G., Gary, G., Neelam, P., & H. Ken, C. (2014). Do outdoor recreation participants place their lands in conservation easements? Nature Conservation, 9, 1-18. doi:10.3897/natureconservation.9.7981

Roberson, D. N., & Babic, V. (2009). Remedy for modernity: experiences of walkers and hikers on Medvednica Mountain. Leisure Studies, 28(1), 105–112.

Scannell, L., & Gifford, R. (2013). Personally relevant climate change: The role of place attachment and local versus global message framing in engagement. Environment and Behavior, 45(1), 60-85. doi:10.1177/0013916511421196

Schultz, P. W. (2000). Empathizing with nature: The effects of perspective taking on concern for environmental issues. Journal of Social Issues, 56(3), 391–406.

Semenza, J. C., Ploubidis, G. B., & George, L. A. (2011). Climate change and climate variability: personal motivation for adaptation and mitigation. Environmental Health: A Global Access Science Source, 1046. doi:10.1186/1476-069X-10-46

Solnit, R. (2016). Hope in the dark: Untold histories, wild possibilities (3rd ed.). Chicago, IL: Haymarket Books.

Xiao, C., & McCright, A. (2014). A test of the biographical availability argument for gender differences in environmental behaviors. Environment and Behavior, 46(2), 241-263.

Wilson, E.O. (1984). Biophilia. Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA

Zanon, D., Doucouliagos, C., Hall, J., & Lockstone-Binney, L. (2013). Constraints to park visitation: A meta-analysis of North American studies. Leisure Sciences, 35(5), 475–493.

Zelezny, L. C., Poh-Pheng, C., & Aldrich, C. (2000). Elaborating on gender differences in environmentalism. Journal of Social Issues, 56(3), 443-457.

Zhang, J. W., Piff, P. K., Iyer, R., Koleva, S., & Keltner, D. (2014). An occasion for unselfing: Beautiful nature leads to prosociality. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 3761-72. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2013.11.008

Appendix A

Hope Topics Shared at Hikes

Osprey /eagle rebound in Southeast Michigan

Development of a Natural River District

Non-profit providing health, youth ed, and community programs in urban area

History and function of the local Ecology Center

Citizen science programs through the local watershed council

Turtle release by local zoo

How a group of people organized to save a woods

Restored natural habitat areas on golf courses

Role of the city’s Natural Areas Preservation department: controlled burns, invasive control, adopt a park etc.

Rain Gardens as part of city initiative to deal with storm water with maps of rain gardens in area and classes available

Stewardship Network

Land preservation

Organic Farm food hub

Certified Wood in Michigan

Local dam removal

Hiking group for moms and babies

A redesigned mall parking lot for storm water retention

Yard planting for birds

New wind turbines that are bird friendly

Hope ideas and hope quotes

Health benefits of forest hikes

Vernal pond mapping in Michigan

Wild turkey comeback

Development of water filter paper for water purification

A new machine to clean trash out of harbors

A device that uses solar energy to purify water

Stores phasing out products with nicotinoids

Appendix B

Sample Secondary Topics Shared in Addition to Hope Topics

Tree ID

Red squirrels interaction with spruce trees

Evergreen ferns

Mute swan issue

Community gardens

Fairy shrimp in vernal pool

Importance of tree snags and fallen logs

Why we pick up dog waste in parks and forests

Historical use of land

Invasive species ID

A place to connect with raptors

Role of wetlands

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Karen Totten, Eric Engel, Carlo Lopez, Joanne Campbell, Irena Nagler, Jamie Bercaw Anzano, and Faye Stoner who helped with editing and feedback. Special thanks to Joshua York who supported the initial idea, and Lisa Brush of the Stewardship Network for her continued support. Thanks to Wayne for teaching me that we are writers and inspirers.

Catherine Dyer works as an educator at the Leslie Science & Nature Center in Ann Arbor, Michigan. She is a Certified Interpretive Guide, former public-school educator, and a graduate student in the Teaching of Conservation Biology through the Global Field Program at Miami University. She considers herself a student of the local forests and watersheds. Contact: dyercs@miamioh.edu

Catherine Dyer works as an educator at the Leslie Science & Nature Center in Ann Arbor, Michigan. She is a Certified Interpretive Guide, former public-school educator, and a graduate student in the Teaching of Conservation Biology through the Global Field Program at Miami University. She considers herself a student of the local forests and watersheds. Contact: dyercs@miamioh.edu

Beautiful writing Cathy. I just finished reading it. It could be a chapter for your book. Yes it would be nice to get together. We were in Florida about a month ago and saw your Mom and Dad. Keep writing it could be the beginning of a new career.

David

I found this article timely and down to earth. People are crying out for projects, activities and media that instills hope for environmental restoration. I think Cathy offers some practical insights on how to do that with women.