While sustainability is often perceived from a framework of fear, emergent understandings of sustainability are rooted in pedagogies of hope. In particular, radical hope, or critical-transformative hope, is transforming sustainability. Radical hope is contextually dependent and is made meaningful when in action. Collective movements such as the buen vivir social movements and transition movements are realizations of radical hope in praxis. Overall, this paper aims to demonstrate that through a multiplicity of movements, sustainability is in the process of continual becoming.

Continue Reading

Abstract: Although the Decade of Education for Sustainable Development (2005–2014) was a period of rapid pedagogical revitalization and innovation, much sustainability education today is still delivered using transmissive and instrumental pedagogies common across higher education. Now that the field has integrated many of the insights from the decade, students and facilitators should continue innovating along themes consistent with the goals of sustainability: transformation and emancipation. Yet, more clarity is needed about pedagogical approaches that will transform and emancipate students, allowing them to become innovators that change existing structures and systems. This paper presents a framework combining four interacting (i.e., complementary) pedagogies (transmissive, transformative, instrumental, and emancipatory) in sustainability education, helping to reify pedagogical concepts, rebel against outdated curricula, and orient facilitators/learners on their journey toward transformative and emancipatory learning. The authors begin by reviewing the evolution of sustainability education and transformative learning theory prior to introducing the framework. The paper concludes with a vision of sustainability education that incorporates contemplative pedagogies as essential methods in a field in need of cultivating hope, resilience, and emergence.

Continue Reading

In order to develop bioenergy into a viable industry capable of providing valuable energy and employment, there is an immediate need for a workforce prepared for the impending challenges of this emerging, interdisciplinary industry. To meet this need, it is necessary to identify and prioritize the topics that should be included in a college-level bioenergy curriculum. We implemented a three-round Delphi study to determine components of a college bioenergy curriculum in the US, by establishing consensus among a panel of American bioenergy experts. Round One consisted of a single open-ended question: Keeping in mind the future of a commercial bioenergy industry, what content knowledge should a student have upon completion of a college-level bioenergy curriculum? Responses were qualitatively coded into themes, and experts were asked to rate the importance of each theme using a five-point Likert-type scale during subsequent rounds. The final round resulted in 13 themes: Energy Basics, Types of Bioenergy, Environmental Impacts (including Life Cycle Analysis), Current Technologies, Societal Issues, Logistics, Policy, Biomass Composition, Non-Bioenergy-Specific Fundamentals, Biomass Production, Conversions, Bioenergy Market, and Business-Related Knowledge. Results will be used to bolster the existing bioenergy education initiative at Oregon State University, and can provide guidance to other institutions in the US and abroad interested in developing similar bioenergy education programs.

Continue Reading

Engaging students not majoring in science, sustainability or environmental studies in learning environmental literacy and shifting their attitudes and behavior toward nature often requires a multi-perspective approach and presents unique challenges. We sought to: (1) pair artistic perspectives with botanical concepts to educate and interest our students in learning environmental literacy, (2) engage our students in careful observation and visualization of nature, and (3) increase the environmental sensitivity of our students by connecting botany with nature based art. To do this we designed a pre-class assignment, an in-class botanical art workshop, and a written reflection assignment that asked students to view, conceptualize, and create works of botanical art as a multi-perspectival process of engaging with relevant scientific processes and environmental concerns connected to botany. Here we provide a justification for the value of bridging science with art, detail our approach, describe student survey responses and thoughtful written reflections, and illustrate lessons learned and future plans.

Continue ReadingHuman beings today are living in times of unprecedented social and ecological crisis, a crisis that is to a significant degree of human making. The impending arrival of the Anthropocene geological epoch gives this crisis a name. As academics with a sense of responsibility for our relationships with planetary kin, the awareness of unfolding crisis calls on us to reach a deeper understanding of assumptions about the world, and of modes of living that these assumptions permit, which have been a human contribution to crisis. Furthermore, the Anthropocene calls us to act upon our new understanding. Taking modern European imperialism as a key generative force in the development of Anthropocene, we provocatively develop the idea in this article that the life-ways and worldviews of Indigenous Peoples colonized by European imperialism – including, potentially, marginalized and suppressed life-ways and worldviews of Indigenous Europeans – may hold critical insights by which to negotiate the Anthropocene and to challenge and change habits of thought and action that have led us to its threshold.

In doing so we outline the rationale behind the Alliance for Intergenerational Resilience (AIR) whose objective is to build social-ecological resilience by connecting and supporting locally based projects for the innovative and renovative co-evolution of social and ecological systems. AIR aims to generate inter-cultural relationships between Indigenous communities and communities no longer considered indigenous to place in order to support more meaningful, life-giving social and ecological relationships for all people. In order to further describe AIR’s objectives and its aspirations, the article draws on the Alliance’s inaugural event, the Elders’ Voices Summit, four days of Indigenous-led sustainability education with more than 100 international participants, representing community, university, government, philanthropy and not-for-profit sectors. We conclude by casting our hopes forward to envisage future re-indigenization work that supports the connection and reconnection of human beings with the Earth and the places of the Earth to which we belong.

Continue ReadingAbstract: This thought piece proposes the adoption of a new “3 Rs” to inform a climate-responsive environmental and sustainability education (CRESE): reclamation, resilience, and regeneration. As a changing climate becomes the larger campus of our learning, denial and top-down emergency preparedness both prove to be insufficient. We are invited into a deeper approach. Reclamation and resilience fold in (1) the saving of enduring biocultural lifeways and patterns and (2) the dynamic flux-states of panarchic socioecological resilience models. These two partner with (3) regeneration: context-responsive social collaborations; eco-socially-embedded capacity building systems; and the promise of regenerative design. These three approaches allow us to re-envision educational systems and encounters that are proactive rather than only reactive or responsive in metabolizing persistent climatic volatility. These three approaches – reclamation, resilience, and regeneration – echo the three approaches to climate change that Pelling has suggested (2009) – mitigation, adaptation, and transformation. Note, however, unlike Pelling’s model, these approaches are conceived as simultaneously requisite literacies and movements rather than as competing. Reclamation, resilience, and regeneration represent ever-more-complex types of capacities and support capacity building aimed together toward life-supportive, dynamic, complex systems transformations. Environmental and sustainability education that fosters skills of reclamation includes preservation, conservation, recording, and the establishment of libraries and sanctuaries of exemplar systems. Environmental and sustainability education (ESE) for resilience includes network extension and adaptive capacity building. ESE for regeneration nurtures emergent complex systems metacognitions, creativities, and transformative, transgressive social approaches that are connective, disruptive, and innovative and model and embody complex emergence. Regenerative ESE fosters skills to facilitate catalysis of emergent regeneration, self-organization, and transformation into more complex living systems. All of these position embedded learners in pro-active, systems-intensive embodiments of the types of living networks that foster survival, flexibility, thriving, and phase-change during our entry into a time of consistent climate turbulence.

Continue Reading

This case study describes a problem-based and service learning module in which undergraduate students participated in a community-based project. Students joined a group consisting of local non-governmental organizations (NGOs), public and private organizations, concerned citizens, and city officials to tackle issues concerning the local watershed. The case study took place over a number of years from 2014 to 2016 and will continue in subsequent academic years with a new group of multidisciplinary students.

Students put together documentation for a grant application that resulted in the city receiving $2.5 million dollars in grant money towards sustainable stormwater management systems. This aspect of the project included extensive data collection and analysis, much like the kind of work water conservationist in the field would perform. Students continued the work by using the data to plan and design appropriate, site-specific best management practices (BMPs) for the campus and in subsequent courses will implement these designs on site.

The mode of instruction described in this case study proved quite engaging to the students because it put them in the heart of an actual local project, doing work that was removed from a purely academic exercise – thereby offering a real-world scenario as field employees. The goal is to provide hands-on instruction that inspires and engages students and allows them to apply concepts of watershed management as a service to their local community.

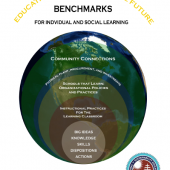

This document is a provisional draft that has emerged out of an initial “State of the Field” issue and database, published in JSE in 2014 and a follow-up conference in Winter of 2015.

Jaimie Cloud of the Cloud Institute has been the lead organizer and author of this document. See the opening pages for the large number of additional contributors.

A process for comment and revision will be announced during Spring/summer 2016.

Continue Reading

Abstract: Development of a sustainable relationship with our natural resources is an imperative for any meaningful quality of life as climate change poses the ultimate test of our adaptability as a species. The consequences of failing to respond will be catastrophic and irrevocable over a millennial time scale. During the environmental century, higher education has an ethical imperative to provide the foundation of a sustainable civilization. Higher education is broadly failing to meet this mandate. Most existing programs in environmental and sustainability science and studies provide inadequate training and lack budgetary autonomy equivalent to established academic units. Although many universities define sustainability through operational activities, the primary purpose of higher education is not operational sustainability — it is teaching, learning, scholarship, and outreach. Developing the capacity for proactive adaptation will require us to examine how we conduct teaching and research across the spectrum of higher education institutions. Education and research for proactive adaptation to rapid ecological change affecting human and natural systems is necessary if we are to produce holistic managers to conserve our natural heritage. All undergraduates should acquire basic ecological and sustainability literacy. Teaching, learning, and scholarship for sustainability must become the highest priority in higher education. Collectively, faculty have the power to implement these reforms.

Continue Reading

Abstract: Writing an essay about hope in these times feels like an indulgence of privilege. Still, with full awareness of the implications, I want to insist that we not lose hope, that we make it meaningful, and that we go so far as to make its cultivation a central focus of our lives and work. This essay is intended to serve as a calling card for like-minded inquirers to reach out across time and space, to find ourselves and one another in the engaged optimism of meaningful work in the world, and as an acknowledgment of appreciation for all of those who do so.

Continue Reading

Sustainable being is the concept of living a lifestyle that is grounded in physical, mental, emotional and spiritual wellbeing. In this article the author shares how her experiences and learning during a sabbatical in India and Germany helped her make the connection between sustainability education, change initiatives, whole health and heartful living. An overview of sustainable being is provided in the context of five principles of living shared by a vedic-eco community in India who is involved in global sustainability efforts. These principles are related to those living in western society with an emphasis placed on the role of sustainable being for educators involved with change initiatives.

Continue Reading

The ecological crisis is a crisis of relationship, and the way forward lies in building more reciprocity, respect, and love into human relationships with each other and with the rest of nature. What is needed is a great economy of give-and-take in which what each takes in is balanced by what each gives out. Nature provides the model for this reciprocity in the biological process of breathing in and breathing out. The rhythm of the breath, found in every life form as well as in every larger community in which living beings participate, provides a powerful model for human decisions and actions in every arena of life. By copying the rhythm of the breath, humans can learn from the wisdom of nature’s economy to revolutionize our relationships with one another and with the larger-than-human world. I discuss the economic model of the modern world and its devotion to linear increase and accumulation, or breathing in without limit, and how profoundly this pattern contradicts the reciprocal model of biological life. I offer historical examples of reciprocal economies among the Northwest Coast Indians in the potlatch ceremony and among ancient Israelites in the Year of Jubilee. I then offer examples of reciprocal practices that emphasize the breathing-out or giving-back half of the breath cycle and that can be practiced in daily life. I suggest that activities of any kind that engage people in giving back, such as showing appreciation, extending care, or pausing for meditation, contribute directly to sustainability because they address the giving-back half of the breath cycle, which is missing or underexplored in modern life.

Continue Reading

With elegant simplicity, Rick Medrick makes the case for the importance of transformational change as part of our education process to bring about sustainability. He brings forth the need for creating learning environments where real, transformational change, can happen. And he invokes the role of the “servant-leader” in establishing those environments as part of an organic and evolutionary change process that we can help to generate.

Con una sencillez elegante, Rick Medrick hace el caso por la importancia del cambio transformacional como parte de nuestro proceso educativo para llegar a la sustentabilidad. Trae al frente la necesidad de crear ambientes de aprendizaje a donde el cambio verdadero transformacional puede ocurrir. Y el invoca el papel del “líder-sirviente” en establecer estos ambientes como parte de un proceso de cambio orgánico y evolutivo que nosotros podemos ayudar en generar.

Kathy Lamborn shares her profound wilderness moments with us, much like she does with her middle school students in the classroom. But she goes on to make the case that the value of wilderness is not just for its own sake but for its power to elicit these moments and thereby bring us “to our knees with reverence,” helping us to recognize the call for a just and compassionate—“sustainable”—life.

In an insightfully pragmatic way, John Gookin shows us how we can incorporate sustainability concepts into an innovative curriculum like that of NOLS without forcing the issue. He espouses the NOLS “organic” approach to curriculum design, where each taught element serves a real purpose, while finding great instances for including sustainability theory and practice.

Continue Reading

In this convincing argument, Tina Evans makes the case for both social and ecological components to sustainability that each of us realize, individually and in community, in the context of our own “lifeway.” She also portrays, in concise terms, the transformational process that she incorporates into her own lifeway as a college professor.

Continue Reading

In this rich and robust view of sustainability, Jordana DeZeeuw Spencer accounts for the need to survive in a sustainable environment; at the same time, she takes the concept to another level and calls for a multi-dimensional view where social justice and intentional, inclusive communication are what bring richness to a sustainable life.

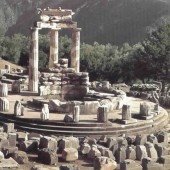

In her vision for sustainability education, Esmeralda Guevara analyzes how Western culture seeks happiness to the exclusion of living a full life, which inevitably involves knowing pain. Material wealth can buy that happiness, but perhaps at the cost of spiritual fulfillment. By returning to the age-old creed “Know thyself,” argues Guevara, we begin down a road to sustainability that recognizes the importance of ecology as well as economics, and spiritual richness as well as material wealth.

Continue Reading