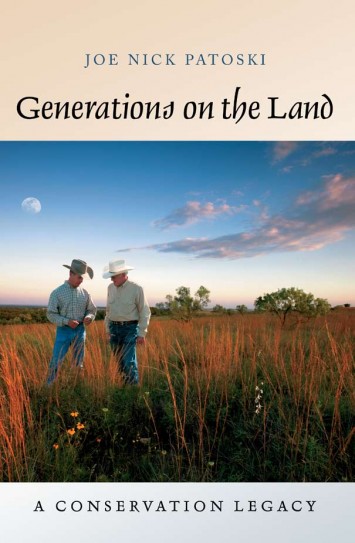

Generations on the Land: A Conservation Legacy, by Joe Nick Patoski. A review.

The landscape of any farm is the owner’s portrait of himself.

The landscape of any farm is the owner’s portrait of himself.

-Aldo Leopold

With regard to management of working lands (private lands engaged in the production of food and fiber), sustainability requires the ability to produce what is necessary for survival today, while understanding the complex relationships within which management of resources must be accomplished to preserve them intact or improved for the future. Generations on the Land: A Conservation Legacy, authored by Texas journalist and writer Joe Nick Patoski, describes some of the skills, motivations, and reasoning behind the progressive land management practiced by eight winners of the Sand County Foundation’s Leopold Conservation Award. Each chapter is a vignette illustrating the difficult and challenging work of six ranching families, a family forestry operation, and a family of vintners.

While well written and interesting, if you are looking for a discussion and analysis of the deeper complex relationships between ecology, production, and economics you will not find it here. This book is not a deep read, and it is not meant to be; this is storytelling. As such it simply mentions a few of the many agro-economic and ecologic realities that fundamentally drive land management decisions.

On occasion the narrative touches on deeper insights. For instance, the loss of jobs and profit margins experienced by local agriculture (silvaculture in this case) as a consequence of downward price pressures is related to global markets unsustainably overharvesting resources:

Terry Peters had witnessed dramatic changes in silvaculture in the thirty five years he had been working these woods. Logging used to be the dominant lifestyle of the region, defined by rugged men wielding axes…and sawmills around almost every bend of the river… But as wood processing evolved into a global industry, the wood workforce in Wisconsin and across the United States declined rapidly. Hanging on in a business where the competition included Brazilian eucalyptus plantations owned by American paper companies, massive logging operations in New Zealand, and clear-cut operations in China, required creative thinking (pp. 44, 45).

The book’s real value is found in what is revealed and implied through the stories told by the working families in their own words. One of the important insights repeated in several of the chapters is a contrast to the view accepted by many farmers and ranchers that regulation and environmentalists are the main threat to ranch viability. The reality of past abuse resulting in degraded lands is cited as most often to blame:

…dad sat on the BLM grazing board…We understood the West was overgrazed…Those were hard times back in the 20’s, 30’s, and 40’s…For (dad) the light went on when President Roosevelt signed the Taylor Grazing Act of 1934. The act held liable every individual party that held a federal grazing permit. Before the act was signed, stockraisers could graze public lands to the point of destroying grasses… (pp. 8, 9).

Decisions to restore degraded lands and to manage within ecologic limits are for the most part enlightened self interest and practical business decisions made to enhance productivity. In addition to greater management options and revenue sources resulting from more productive lands and functioning ecosystems, the skills acquired accomplishing this work are increasingly marketable for those willing to look for opportunities beyond their own fences:

If you can convert to organic, your quality goes way up and…you can command a higher price…We burned this year just out of the need to burn…went the extra mile and received official burn training and certification…secured a $1 million insurance policy to do business as a Conservation Fire Team…consulting and burning for hire all over West and Central Texas (pp. 102, 103).

In addition to acknowledging that restoration has to be accomplished, another hopeful message from these families is the realization that bigger and more isn’t necessarily better. “‘Some people see the land in terms of dollars and wealth’, Teddi Coleman said. ‘We think you can’t put a price on that water, that field. We live in what I call rustic elegance. We don’t have frills, but we have all this natural elegance around us’” (p.63).

By constantly highlighting the true nature of this important work, the author accurately supplies credit where credit is due. For although ranchers, loggers, and farmers relish the ideal of their perceived independence and self-reliance, these stories reveal the partnerships that are essential for restoring working lands. Restoration is complex, costly, and time consuming. Accessing correct information for a particular practice and understanding the latest techniques as they may apply to a specific need takes experience. The work is costly and labor intensive. Mistakes often make things worse than before the project began. Fortunately there are many federal and state programs offering technical and cost share assistance. Private conservation organizations also work to help landowners achieve their restoration goals and are also able to supply volunteers and low cost labor. This is good public policy in practice, which until recently enjoyed bi-partisan political support. Maybe the horrific and costly fires this past summer will remind more short sighted politicians about being “penny-wise and pound foolish.”

In addition to celebrating the accomplishments of the families that are its subject, this short enticing book also helps as a bridge across the political and cultural gaps between working families and those of us who, while not daily working land for a living, share common interest in healthy sustainable food-systems and ecosystems. It touches on complex issues in a way that offers a non-threatening opening for ranchers and non-ranchers to talk and think about the management of working lands. This in essence is at the heart of applied sustainability education.

Richard Pritzlaff is President of the Biophilia Foundation and a third year Ph. D. student at Prescott College. Pritzlaff has over 15 years of experience in land conservation and active mangement and restoration of habitat on private working lands to benefit wildlife. For the past three years Pritzlaff has been developing private and public financing and ecosystem services credit markets to help transition farms and ranches to more sustainable food production.

Richard Pritzlaff is President of the Biophilia Foundation and a third year Ph. D. student at Prescott College. Pritzlaff has over 15 years of experience in land conservation and active mangement and restoration of habitat on private working lands to benefit wildlife. For the past three years Pritzlaff has been developing private and public financing and ecosystem services credit markets to help transition farms and ranches to more sustainable food production.

[…] Read the entire review at the Journal of Sustainability Education Share […]