Breaking down barriers to university-community engagement: a Master’s student-led sustainable agriculture workshop for children in Costa Rica

Sylvester et al JSE December 2017 General PDF

LINK: December 2017 General Issue: Curriculum and Change Table of Contents

Introduction

Universities have great potential to educate community youth. Universities are sites of knowledge generation and its dissemination is central to their mission. This potential has not always been sufficiently exploited in communities neighboring universities for a number of reasons including: cultural differences among community members and academics, a lack of incentives (e.g., policies around promotion and tenure), and a lack of resources for faculty and staff to spearhead these initiatives (Kezar & Rhoads 2001, Fryer year unknown). Despite these limitations, universities have a knowledge-rich student body looking for opportunities to engage in outreach in some form (e.g., volunteering, service learning, and social action). Research illustrates that university students want to participate in volunteering or social action for multiple reasons including: improving their Curriculum Vitae, gaining practical experience, helping others, working for important causes, making professional contacts, making friends, and relieving stress, among other reasons (Universities UK and NUS 2015, Birgitta & Yamauchi 2010, Smith et al. 2010).

At the United Nations-mandated University for Peace, Master’s students are encouraged to translate university knowledge into social action. The majority of these students engage in this social action in their home countries after completing their degree requirements; however, these students are interested in volunteering and social action while completing their degree in Costa Rica. Specifically, students commonly express interest in gaining experience beyond their classrooms and specifically with youth in surrounding local communities.

Our project’s main goal was to meet Master’s students’ needs to gain experience beyond the classroom through university-community engagement. Our project is unique in that we did not approach our goals from a top-down perspective, i.e., inviting Master’s students to participate in an existing university outreach program; instead, we asked Master’s students to take on the role of researchers and educators in the design and execution of our community engagement work. Empowering Master’s students as leaders in the process is important for them to: 1) gain self-confidence as emerging professionals, 2) create a project that is relevant to their own learning needs, and 3) to engage in higher levels of learning (i.e., creating and educating; Anderson & Krathwohl 2001).

Because we carried out this project within the Department of Environment and with students from the Sustainable Food Systems program, we chose to support community food security and sustainable agriculture. In Costa Rica and internationally, there is concern that some youth are uninterested in farming (White 2012) and that our current agri-food industry has resulted in the deskilling of young consumers (Jaffe & Gertler 2006). Our project was designed creatively by Master’s students to teach community youth about food security and sustainability in ways youth could connect to these teachings (e.g., music, drawing, hands-on practice).

Our project’s secondary goal was to strengthen university-community engagement for a few main reasons. Although the University for Peace has community engagement as a continuing ambition, this activity has not reached its full potential in the local communities surrounding the university due to a few key challenges. First, few university students speak Spanish, the native language of Costa Rica, which poses challenges reaching out to community schools. Second, there is a lack of funding and incentives for professors and/or students to create programs for community members. Third, a large portion of professors come from out of country and do not hold permanent positions; this creates a barrier to forming in-country networks and relationships central to community engagement.

Case study context

The United Nations-mandated University for Peace

The United Nations (UN) mandated University for Peace is a private university established in 1980; it was established under its own charter and thus, is not subject to UN regulations. The majority of the university’s students enroll in its Master’s programs in English and are on campus around nine months. We worked with students in the Department of Environment, Development, and Peace. This program is interdisciplinary and Master’s students specialize in Environmental Management topics including Sustainable Food Systems, Water Security, Climate Change, and Natural Resources Management. Students choose an internship or a thesis to complete their degree and the majority of students’ professional goals relate to social justice in academia, policy and/or practice.

University extracurricular research group

Outside of regular class time, Master’s students were invited to form an extracurricular research group by Olivia Sylvester, Assistant Professor in the Environment, Development, and Peace program at the university. Due to the short time students have on campus (nine months), we started research group meetings early on in the academic year to ensure students could build relationships amongst each other and with the professor. Furthermore, because participation in this research group was not for credit, we wanted to ensure we had plenty of time to plan our project considering it would compete with other student academic and non-academic activities. The majority of students in this research group specialized in Sustainable Food Systems and their professional goals included: working in academia, education, civil society organizations, and/or in policy.

The professor suggested that our research project be planned as transformative research, i.e., to propose a project whose outcomes would lead to positive social change. All students at our initial research group meeting agreed. Our project would be transformative for three main reasons. First, because its aim was to empower those whose voice is not often heard in research (graduate students). Second, because its end goal was to increase community knowledge about sustainable agriculture and food security. Third, because its aim was to strengthen university-community relationships for knowledge sharing.

The original idea for our research was working with community school children; this was proposed by the professor and students were invited to talk about it and/or propose an alternative. Presenting one idea was important to get our conversation started, because, as we discuss below, many students felt uncomfortable or unprepared to take the lead at the outset in a role generally allocated to a professor. Students decided to continue with the idea of working with community children; from this point on, the project was designed by Master’s students with minimal input from the professor. Students were however, encouraged to use the teachings they had recently received in their own Master’s program regarding sustainable agriculture, and to translate these teachings in some way for community youth.

Different ideas were proposed to work with community children (i.e., educating at local schools, creating vegetable gardens at local schools). Students finally decided on hosting a workshop for community children using the community garden on campus. The Master’s students decided to have our workshop on campus because: 1) they created this garden and thus felt connected to, and knowledgeable about, this site, 2) the project did not have funding for materials for a workshop off campus, and 3) students wanted to introduce community children to our university campus, because it is a campus that is not frequented by Costa Rican nationals (despite being well known internationally).

Master’s students were invited to become equal partners in the project (from planning to execution and publication write-up). The students self-selected their roles in the project based on their time and interests. In total, nine students decided to plan and participate in the work with community school children. Individually, they had different levels of agricultural knowledge but most of them were new learners of sustainable agriculture.

We considered our work both transformative research and social action because our goal was to empower Master’s students as researchers and educators while critically analyzing this process. At our institution, Master’s students are interested in learning more about research before they decide to do a Master thesis (versus an applied project); thus, we designed our work as research and Master’s students took reflective journals as sources of data documenting their experience in the process (e.g., Borg 2001). Students were encouraged to reflect on the project’s power dynamics, our group communication and decision making, as well as the successes and challenges in project design and execution. In addition to reflective journals, during our in-person meetings students reflected on our project power dynamics and how they were coping with the workload.

Finding a community school for our workshop

The research group chose to invite a private versus public school to overcome a language barrier. Many private schools in Costa Rica teach core classes in English and this was the language spoken among our Master’s students. Specifically, we worked with students of the fourth grade at Blue Valley School and our collaboration was directly with their teacher Mr. Dobrota. This collaboration was facilitated because one student researcher, Janaya Greenwood, knew this teacher personally. In total, 26 fourth graders attended the workshop along with their teacher and teaching assistant.

Planning and executing workshop activities

Master’s students decided on holding a workshop in the garden and designed four workstations for the school children. These stations included: 1) plant identification and knowledge sharing, 2) composting and beneficial pests, 3) creating organic fertilizer, and 4) planting with song. To better manage the large group of students and allow for more meaningful participation, the fourth graders were divided into smaller groups (6-7 students) and rotated through the four stations. The children were also given a worksheet to take notes or draw about what they saw and learned at each station.

To break the ice with the children and to make the topic of sustainable agriculture more engaging to them, our workshop leaders chose garden nicknames derived from names of food and nature; an activity which inspired laughter and relieved nervousness amongst the children. This was designed to not only act as a fun activity, but also to start a conversation regarding the diverse crops grown for food. It was interesting to learn that some crop nicknames were known to all children (e.g., pineapple), whereas other crops (e.g., arugula), were only known to a few.

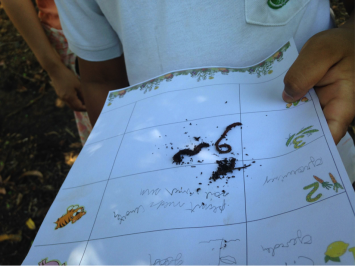

It is well documented that learning by doing is an effective way to retain information (Kolb 2001), and thus, we incorporated multiple elements of hands-on practice in our workshop; these elements included: shoveling and mixing organic fertilizer, digging and planting seeds, massaging and tasting crops, and holding worms from the soil (Figure 1). We complemented this learning style with note-taking and drawing. Children were given a sheet of paper where they could write down or draw something they saw and/or learned at the different stations (Figure 1). The children seemed to take this activity very seriously. Many did not want to leave a station without completing their notes to ensure that they didn’t forget the important things they had just observed.

Figure 1: One fourth grader at the Composting and Beneficial Pests workstation examining the behavior of worms used for vermicomposting.

We also included music to enhance children’s interest in gardening and to connect with the children. According to Turner and Freedman (2004) the use of music in environmental education can help students learn because it can: 1) present teachings in musical lyrics and 2) help people value nature if nature is also understood as musical, and 3) can help build empathy of the natural world. Music is also an important tool because it can transcend geographic locations, cultural, and socio economic differences (Smiley & Post 2014). In our case, many of the Master’s students were from different countries and cultural backgrounds than those of our invited children participants (the majority were Costa Rican born and raised). Because we did not know the school children before our workshop, we used music as a way to connect with them in general and to talk about agriculture. Specifically, at our planting station co-author Tiyamike Mkanthama played the bongos and performed a rendition of a popular American folk song called Garden Song written by David Mallett (Figure 2). Children were invited to sing, dance, clap, or snap fingers along with the music. Music was also used when students were invited to plant seeds; specifically, they were given the space to talk to, massage or sing to the seeds and plants to aid in their growth (Figure 3). Here some children chose to sing popular songs together and this allowed them to connect to agriculture in their own ways rather than only in the context of the song our workshop leaders chose.

Figure 2: Co-author Tiyamike Mkanthama playing the bongos as an invitation for children to connect with gardening through song.

Figure 3: Co-author Janaya Greenwood inviting children to sing to the seeds as they planted to aid in their growth.

Critical reflections on the workshop: recommendations and areas for improvement

Empowering Master’s-students as educators and researchers

In a workshop led by Master’s students, we recommend working in a setting where these students feel comfortable and to which they feel connected. Our garden was built by the same students that led the workshop; having this connection and sense of place was central to increasing Master’s students confidence as educators about sustainable agriculture. Co-author and Master’s student Janaya Greenwood explains:

“Knowing the garden’s ins-and-outs allowed us to confidently plan and execute a workshop located in an environment that we were the experts of. This familiar space, complete with all of the materials needed to lead a lesson, became our classroom and the visiting youth became our students. After the workshop I sat with the youth group during their lunch and one of the young girls was surprised when I told her that all of the workshop leaders were students and that this was our school garden. Her confidence in us as teachers affirmed that we could take on this new role when given the opportunity and the right tools.”

We further recommend that professors support Master’s students’ autonomy in the design of the workshop; this includes, being an observer in meetings rather than an instructor and allowing students to experiment and to test methods that might be unknown to the professor guide. Janaya Greenwood describes how this autonomy was important:

“Throughout my education, there has always been this invisible line which seems to separate the students from the teacher. As a student you are always trying to meet the expectations of your teachers in discussions, on assignments, or during tests. Your teachers are the experts and in traditional classes they set guidelines for your participation and learning. However, during the planning and execution of this workshop that line faded because we, the students, were in charge of creating our own guidelines in an environment where it was evident that our professor was also learning from us. Through group collaboration, and with support rather than specified direction from the professor, students decided on the most important elements to be shared with youth and how to accomplish this. This self-regulation and creation fostered a sense of responsibility, autonomy, and also excitement amongst us in the development of something that was entirely our own.”

Furthermore, supporting Master’s students autonomy to experiment was critical to developing creative ideas that may not be within the range of ideas or expertise of the professor. Olivia explains that including music and singing in the workshop would have been out of her comfort zone considering this is not a conventional teaching technique, nor was it one she had previously tested. Master’s student workshop leaders were eager to experiment and proposed many ideas that the professor had not thought of (e.g., garden names, music, drawing the garden from a bird’s eye view).

Overall, flattening power dynamics in academia can be challenging because it can be out of the comfort zone of professors who are used to leading, and of students who may not feel confident in their ideas for research or teaching. Students may also lack the confidence to share these ideas in front of professors that are seen as experts on a topic. Co-author and Master’s student Monika Bianco explains that “although extremely excited by the project, I found it slightly intimidating at the beginning of the semester to be encouraged by the professor to form part of its leadership.” The sense of intimidation and unpreparedness to apply knowledge outside of the university classroom has also been reported by students from other universities (e.g., an expectation gap; Millar 2014). Our findings combined with the reported expectation gap illustrates why we need more spaces where Master’s students can take on the roles of educators and researchers to ease their transitions into their professions. Masters student Janaya Greenwood elaborates on this:

During my undergraduate studies, and through much of my Master’s, what is taught in class is predominantly theoretical. My studies at the University for Peace, specifically within the Environment Department, have differed from previous educational settings since it has helped to develop both theoretical and practical skill-sets that can be utilized outside of a purely academic setting. Many students have to wait until securing an internship or employment to develop the skills that I was able to obtain through class projects and the extracurricular research group.

There were some limitations, however, in regard to efficiency and commitment which may be expected from this type of project organization, especially among students who are not accustomed to it. From the project’s initiation, the students agreed to participate as much as they could throughout the year and that the project would grow organically and experimentally based on the time and resources available, which were unknown at the time. The results of this agreement were that 1) only those with a high interest level participated, 2) leadership was slightly staggered and 3) the project development moved slowly. It would have been more efficient for the Master’s students to sign up for specific leadership roles (i.e. planning meetings, organizing tasks, communication) and to have someone to be accountable to. For example, too many tools for communication were used in order to accommodate everyone’s preferences (e.g., email, google documents, facebook, whatsapp) and this often resulted in confusion and lack of timely responses. Despite a level of inefficiency, Master’s students expressed that the overall advantages of the project’s organization outweighed its limitations. Specifically, Monika Bianco explains:

Students were given a unique opportunity to build their research skills in an encouraging environment in which they were the ones responsible for the resulting successes and benefits. Students learned to take risks and get out of their comfort zones, to have confidence in their own knowledge, and to manage their time and commitments throughout the year. Most students were unaccustomed to the balanced power dynamics encouraged by the professor. This project has shown, however, that if this style of research becomes more prevalent at the university level, it could lead to more empowered and confident graduates and young professionals.

We found it challenging to equitably share the workloads and benefits of the project. Specifically, this was a volunteer project, so people could commit to as much or as little of the project as fit with their schedules. Due to this voluntary nature, neither the workload nor full benefits were shared equally by all who participated. Of the nine people that partook in the execution of the workshop, only five people took on leadership positions (e.g., planning activities and working at each station) and the other four walked student groups around garden stations (i.e., assistant roles). That not all Master’s students took on leadership roles could have been due to their personal preferences, their English language abilities, and/or their experience and comfort teaching. To better share workloads and to give all students opportunities to take on leadership roles, we suggest organizing a follow-up workshop where those who might have wanted to try out new roles would have been given a chance to do so.

One important element to consider is how the role a Master’s student played in our project can affect the benefits they acquired from it. Specifically, only those who were station leaders volunteered to be a part of the write up of our workshop outcomes. Although it is impossible to directly link workshop role with willingness to write up an article due to other influencing factors (e.g., comfort with English, availability), it is important to consider our observation, i.e., that those Master’s students with more active roles, were those who followed the project to completion and receive additional professional benefits (i.e., co-authoring an academic paper).

Some of the students are already beginning to benefit from this workshop experience, not only from the skills acquired, but also from the confidence it has generated. Specifically, Monika Bianco explains,

After completing my Bachelor of Arts degree, I felt that I lacked practical tools to bring into the workforce and, as a result, decided to pursue a Master’s degree. Although I have learned a great deal this year, if not for this workshop, I’m afraid I would have graduated with a similar sentiment. This experience’s value has been demonstrated to me recently on two different occasions. Firstly, during my internship at the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, I was asked to apply the specific knowledge I acquired in the workshop to develop a national document on how to teach the Costa Rican curriculum through school gardens. Throughout most of my internship I felt like I was being taught by my colleagues, so the fact that I could contribute this information made me feel valued and respected in my workplace. Secondly, in a recent job interview for an NGO working in community development, I was asked what practical skills I could contribute to the team. The interviews were very interested in my garden workshop experience and I feel that it has increased my potential for employability. Moreover, I believe the research aspect of this project has helped me describe the benefits of such an experience to future employers and has given me confidence in making the challenging transition from student to professional.

Lastly, the workshop, inspired creativity regarding knowledge transmission in Master’s students that is not always captured in a classroom setting. Hana Nagano, explained how working directly with youth allowed her to see different angles of teaching and learning; she explains that:

The experience in the workshop and research group reminded me of the importance of environmental education from an early age. Since I studied fine arts before and am passionate about painting, currently I am thinking to combine my painting and environmental education through creating a children’s book. If I wouldn’t have had the experience in the workshop and with group members who are passionate about the environment, I would not have such an idea.

2. Sharing farming and food security knowledge with children

One strength of our workshop was the inclusion of a diversity of teaching techniques including hands-on practice, singing, note-taking, drawing, and observation. This diversity was important to support children with different personalities, learning styles and skill levels/capabilities. For instance, we observed that while some were very engaged in shoveling and holding dirt and worms, other students did not want to get dirt on their hands or clothing. Therefore, having the option to write or draw was important to include those that did not want to get dirty.

We also learned that despite English being the school’s primary language, not all students had the same language competency. Having hands-on practice was critical so that those with lower levels of English, that may not have been comfortable asking questions or did not understand verbal directions, could participate without feeling excluded; in our workshop, this included one recent transfer student that despite having next to no English competency, was involved in all the hands-on practices.

Hands-on practice further stimulated the sharing of teachings about organic farming that go beyond food-growing facts. One of our stations was designed to convey land ethics associated with organic farming, i.e., caring for the health and rights of the land and all of its beings (IFOAM 2017). At this station students were encouraged to touch, talk, and to sing to plants. This station was well received by children and one child shared that her mother, who has a vegetable garden at home, taught her of the importance of being nice to plants and that they should be given care and love for them to grow well. Thus, our work illustrates how experiential learning spaces can help not only teach agriculture facts but deeper land ethics that are important to counter our modern food system’s tendency to alienate people, and especially youth, from the processes of food production (Jaffe & Gertler 2006).

There were two activities that were popular among all students: singing with the bongos and seed planting. Planting was popular even amongst the students that did not want to get very dirty in the other activities (e.g., fertilizer making, shoveling). We found it particularly beneficial to include one song that we chose but then to let students sing to the plants with the song of their choice; we observed that this allowed the students to connect to farming in a way that was less structured and inviting them to include their identities in the process.

It was also beneficial to include a diversity of workshop leaders so children’s learning goes beyond that of agriculture. Our workshop included Master’s students from five different countries. We found that many children did not only ask about farming but also about our languages and cultures; Monika Bianco describes this:

At my station, I talked about growing food in Costa Rica but I also compared it to the Canadian context, for example, our winter/short growing season, how we import foods from Costa Rica (ie.pineapples and coffee), and what vegetables are commonly grown in both countries. The children seemed interested to learn about my country and how it was both similar and different from their own in terms of food!

It was also important to have the children’s school teacher and teaching assistant join the workshop for three reasons. First, because having a trusted person, i.e. their teacher, present in a new environment allowed for feelings of comfort and ease in a new situation, while also maintaining a sense of structure. Having two trusted role models partaking in our stations demonstrated proper behaviors and allowed students to relax and interact in similar ways as they would in their classrooms, possibly increasing their level of participation. Seeing a teacher’s interest and enthusiasm on a topic is also known to increase the enthusiasm of their students (Patrick 2000). Second, because the Masters students had never interacted with this group before, and because some students did not have an education background, having the children’s teacher eased concerns the Masters students had in relation to the behavior management of young children (e.g., students with special needs such as one student with autism). Third, because the children were in a new learning environment (the garden) they had a chance to showcase their knowledge about gardening and nature; knowledge that may be previously unknown to their teachers, who educate them in the areas of Language Arts, Math, and Science.

Despite that it is well-documented that many children are uninterested in farming (White 2012) and that our current agri-food industry has resulted in the deskilling of young consumers (Jaffe & Gertler 2006), we found that many children had know-how about farming. Monika Bianco explains:

As a leader of the plant identification station, a great learning opportunity for me was witnessing the children’s prior knowledge in growing food. As a station leader, I was prepared to provide most of the teaching that day. I was delighted to see how many children already knew how to identify a lot of the seedlings and how to identify plants through taste and smell.

Thus, although our workshop was designed to educate youth, being in the garden and interacting with youth in an experiential fashion created a space where children could showcase their own knowledge. Exposing children’s knowledge is important to them being valued as knowledge holders. In our workshop, many of us expected to play the roles of teachers; that this workshop taught us how children can hold important knowledge reveals how garden workshops are not just capacity building exercises for the youth that attend, but for all who partake. Better understanding the knowledge children hold may encourage professionals to design workshops where children can be more active players in their learning, further flattening the power differences in formal education.

3. Strengthening university-community engagement

To better support community engagement, institutional incentives for this type of project are necessary. Specifically, our volunteer research group competed with the time we could dedicate to other career development activities. For the professor this included publishing, grant-writing, research, and teaching; for the Master’s students this included their existing coursework, employment, and planning for their theses or internships. To support professors in community engagement, such initiatives could be included in job descriptions so they hold similar weight to other success indicators (e.g., publications, grants). To support Master’s students, these initiatives could become part of their course evaluations so they do not interfere with their academic achievements. Partial credits could also be awarded to students which would count towards internship or mandatory community involvement hours.

In our case study, it was easier to work with private school children versus those in surrounding public schools. This is concerning because public schools in Costa Rica are often those with a lack of funding for excursions outside of their institutions. We specifically invited a private school that was located in a community 21 kilometers away despite the fact that there is a public school neighboring our university (1.3 kilometers away), one that would greatly benefit from our dissemination. We made the choice to work with a private school for a few reasons. First, our Master’s students all study in English (and not all speak Spanish, the Costa Rican official language and the first language at public schools); thus, to ensure Master’s students could teach, we reached out to an English speaking private school. Secondly, our institution does not have a community engagement fund or program and the private school we worked with had their own transportation to bring the students to our garden.

Working more with private schools means that our university-community engagement program would be more accessible to children that already have increased opportunities to visit universities or go on field visits compared to those attending public schools. Noting the disproportionate opportunities for private school students, we are currently working on creating a partnership with the public school neighboring our university where Spanish is the main language spoken. We share this reflection because it is important to acknowledge how the workshop conditions may be more apt for one sector of the population over another.

Despite our work with a private school that was 21 kilometers away, we believe we met our goal to strengthen community-university engagement. This school had visited our University to use the outdoor park areas, however our workshop was the first occasion where these school children interacted with Master’s students. Furthermore, the University for Peace is the closest higher education institution to this private school.

Conclusions

We wrote this paper to share one example of how Master’s students can lead community engagement where incentives and resources for these initiatives are lacking. Because our workshop was led by Master’s students, it gave them an opportunity to transition from knowledge recipients to educators before entering their professions. Having Master’s students lead community engagement increased the creativity of our project because they experimented with techniques to enhance children’s interest that were new to the professor (e.g., singing about farming, invitations to sing popular music to the plants, and giving workshop leaders garden names). By supporting Master’s students’ autonomy, students reported feeling an increased sense of confidence and excitement after taking on responsibility for project planning and execution; at the same time students also reported feeling intimidated to take on an education leadership role traditionally played by the professor. We believe that one way to address this sense of unpreparedness is by increasing higher education student’s opportunities to lead in classrooms, in research, and in community engagement. Leadership was shared among students, and as a result, we found some activities were more time-consuming and less efficient; however, Master’s students describe that the benefits of experimenting with teaching and research leadership roles outweighed its limitations. Because our workshop was a voluntary initiative, it was challenging to balance its planning with both the students’ and professor’s academic workloads. Lastly, we experienced that working with a private school greatly influenced the success of our workshop because its students spoke English, the school provided transportation for the children, and the school encouraged outdoor education. Because public schools in Costa Rica generally have less economic support for excursions, more effort should be made to support public school children’s participation in university-community engagement projects.

References

Anderson, L., & Krathwohl, D. A. (Eds.) (2001). Taxonomy for Learning, Teaching and Assessing: A Revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational. Objectives. Boston, MA: Pearson Education Group.

Birgitta Pessi, A. & Yamauchi, N. (2010). Social and cultural origins of motivations to volunteer: a comparison of university students in six countries. International Sociology, 25 (3): 349–382.

Turner, K. & Freedman, B. (2004) Music and Environmental Studies. The Journal of Environmental Education, 36(1): 45-52.

IFOAM (2017). Principles of organic agriculture, Retrieved from

http://www.ifoam.bio/en/organic-landmarks/principles-organic-agriculture .

Jaffe, J., & Gertler, M. (2006). Victual Vicissitudes: consumer deskilling and the (gendered) transformation of food systems. Agriculture and Human Values, 23(2): 143-162.

Kezar, A., & Rhoads, R A. (2001). The dynamic tensions of service learning in higher education: a philosophical perspective. The Journal of Higher Education, 72 (2): 148-171.

Millar, E. (2014). The expectation gap: students’ and universities’ roles in preparing for life after grad, Retrieved from https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/national/education/the-expectation-gap-students-and-universities-roles-in-preparing-for-life-after-grad/article21187004/?page=all .

Smiley, S. L., & Post, C. W. (2014). Using popular music to teach the geography of the United States and Canada. Journal of Geography, 113 (6): 238-246.

Smith, K. A., Holmes, K., Haski-Leventhal, D., Cnaan, R. A., Handy, F., & Brudney, J. L. (2010). Motivation and benefits of student volunteering: comparing regular, occasional, and non-volunteers in five countries. Canadian Journal of Nonprofit and Social Economy Research, 1(1): 65-81.

Universities UK & NUS (2015). Breaking down the barriers to student opportunities and youth social action, Retrieved from: http://www.universitiesuk.ac.uk/policy-and-analysis/reports/Documents/2015/breaking-down-the-barriers.pdf.

White, B. (2012). Agriculture and the generation problem: rural youth, employment and the future of farming. IDS Bulletin, 43:9-19.

Olivia Sylvester is an Assistant Professor of Sustainable Food Systems at the University for Peace, Costa Rica. She researches gender, agriculture, climate change, and food security in Latin America using transformative and Indigenous methodologies. Olivia received her Ph.D. in Natural Resources Management at the University of Manitoba.

Olivia Sylvester is an Assistant Professor of Sustainable Food Systems at the University for Peace, Costa Rica. She researches gender, agriculture, climate change, and food security in Latin America using transformative and Indigenous methodologies. Olivia received her Ph.D. in Natural Resources Management at the University of Manitoba.  Monika Bianco is a Master’s student at the University for Peace, Costa Rica. She is currently an intern at the Food and Agriculture Organization, Costa Rica working with gender equality.

Monika Bianco is a Master’s student at the University for Peace, Costa Rica. She is currently an intern at the Food and Agriculture Organization, Costa Rica working with gender equality.  Janaya Greenwood is a dual-Master’s student with the University for Peace, Costa Rica, and Hankuk University of Foreign Studies, South Korea. She researches curriculums and pedagogies in international schools in Costa Rica to support Education for Sustainable Development (ESD).

Janaya Greenwood is a dual-Master’s student with the University for Peace, Costa Rica, and Hankuk University of Foreign Studies, South Korea. She researches curriculums and pedagogies in international schools in Costa Rica to support Education for Sustainable Development (ESD).  Tiyamike Mkanthama is a Master’s student at the University for Peace, Costa Rica. He researches the convergence between scientific and indigenous knowledge regarding sustainable agriculture.

Tiyamike Mkanthama is a Master’s student at the University for Peace, Costa Rica. He researches the convergence between scientific and indigenous knowledge regarding sustainable agriculture.