An innovator for our times: George Goyder and Australian forestry

Summerfield JSE Dec 2017 General Issue PDF

Summerfield JSE Dec 2017 General Issue PDF

LINK: December 2017 General Issue: Curriculum and Change Table of Contents

All religions, arts and sciences are branches of the same tree.

-Albert Einstein

Introduction

At the G20 Science, Technology and Innovation Ministers meeting in Beijing in 2016, the Australian Minister Greg Hunt outlined the National Science and Innovation Agenda which his government had introduced in 2015 (Hunt, 2016). The Agenda reinforced a common belief, seen in various national and transnational innovation strategies, that encouraging more education in the STEM disciplines alone, was vital to ensuring a generation of future innovators working for national economic success (American National Economic Council, 2015; OECD, 2015). And yet the previous Australian Chief Scientist, Professor Ian Chubb, was one who offered a quieter acknowledgement of the importance of the history of science as a facet of that education, and of an interdisciplinary approach to learning the skills required by the successful innovator (Office of the Chief Scientist, 2014). The humanities, he thought, deserved a place at the educational table of innovation. This paper offers an historical case study to demonstrate the contribution that one humanities discipline can make to educating the next generation of innovators for environmental sustainability.

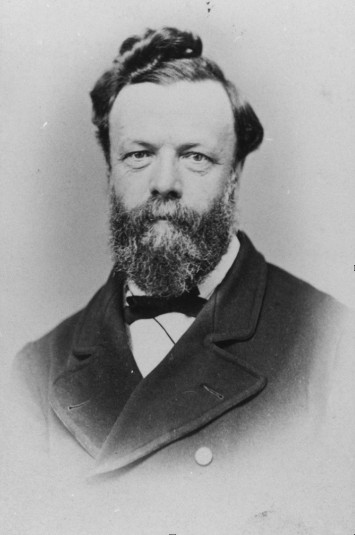

It constructs the historical narrative of the innovation of the first forest management service in nineteenth century Australia, and the first in the independent colonies of the British Commonwealth (Robinson and Johnston, 2001). It does so in order to explore the role played by George Goyder, one of Australia’s early innovators and South Australia’s leading public servant from 1861 to 1893. It then tells the story of Goyder’s education – in what may now be called ‘systems thinking’ – arguing that this was the most powerful enabler of his adult innovative leadership in environmental sustainability.

Defining ‘sustainability

‘Sustainability’ in this paper applies the meaning contained in the OECD’s ‘OECD work on Sustainable Development’. That is, sustainable development is that which:

…seeks to balance the economic, environmental and social [including political] dimensions of development in a long-term and global perspective. It implies a broad view of human welfare, a long-term perspective about the consequences of today’s activities and the full involvement of civil society to reach viable solutions (OECD, 2011).

The beginnings of an Australian forest management service

The language of innovation often conjures an image of the miraculous epiphany of a uniquely endowed person. The word connotes a brand new shiny thing, or system. The idea leaps from conception to implementation with ease because of the obvious genius of the scientific savant who conceived it. There are multiple cartoons, for example, depicting the apparent spontaneous generation of the famous E=MC2 equation from a fuzzy-headed, clearly eccentric Einstein. But, to paraphrase Einstein, he thought of himself as not at all uniquely clever, but rather more prepared to spend longer with a problem than most to reach a solution. The narrative of the innovation of forestry in Australia is a long one too. (And, as we shall see, the length of time spent on the problem is not the only parallel with Einstein).

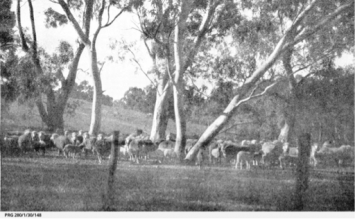

But some think the beginning of forestry in South Australia had a simple, inevitable trajectory: an innovation born entirely of the necessity to produce the fuel and building material for an establishing colony (Tyrell, 1999). The driest colony in the driest continent of the world had limited forest cover when Europeans arrived. This natural scarcity worsened when they began clearing the land, hungry for agricultural production. There is some truth to this view. Sustainable settlement into the second half of the nineteenth century did depend in part on developing a system of sustainable forest management. A summary chronology of the steps leading to its realization seems to reflect this argument of urgent necessity:

1870: a Select Committee is appointed to investigate forest reserves

1873: an Act to encourage forest tree planting becomes law

1875: the Forest Board Act is passed into law

1882: the Woods and Forests Act creates the Department of Woods & Forests

But that simple list belies the messy mix of conflict and inertia it took to get from 1870 to 1882. The parliamentary debates that punctuated the period are an example of what today’s policy makers would call an ‘environmental wicked problem’, or a seemingly intractable mess (Australian Public Service Commission, 2007). It is beyond the scope of this paper to revisit those debates in all of their tortuous – though often highly entertaining – detail. But a summary of the backstory to the above outline indicates the truth of Einstein’s claim: a primary skill of innovation was, and is, being prepared to stay with the problem for a long time. In this case, even if the solution is self-evident to its champions from the outset.

From 1870 – 1873

The story begins in 1870 outside the field of forestry and inside the overarching one of the principles that should govern public land distribution. Goyder had returned from a visit to Victoria. The visit had been for the purpose of reviewing the colony’s decade of changing land Acts – what policy makers might now call a benchmarking exercise. In a report to parliament he confirmed his view of the superiority of South Australia’s practice of land survey before settlement, a fundamental tenet of the colony’s founders in planning an ideal civil society, and one that Goyder had revived as head of the Lands Department. He declared that

[in] free selection before survey there are other evils of a social character, which it is perhaps unnecessary to do more than allude to in such a report as this, but which will press themselves upon a Government determining the mode of settlement of a country. Whatever truth there may be in the statements frequently made that in another colony isolated selection has been taken advantage of to facilitate and protect crime, there can be no doubt that the settlement of a country in this detached manner has a tendency to place the selectors beyond the better influences of society (South Australian Register, 1870).

He wanted regional townships that mimicked the Adelaide city design in every new hundred square miles surveyed. Inside each iconic parkland’s belt would sit community services, especially schools. For parents busy trying to make their land productive, Goyder realized that ‘labor is of the first importance’. But he was concerned that this priority often meant that the ‘distance and expense of schooling is a sufficient excuse…for education being dispensed with altogether’. While applauding the worthiness of ‘hardy men and women’ raised as practical and capable workers, he felt that an imbalance in the developing infrastructure of the new colony would risk producing ‘muscle without a proportionate expanse of mind’ (South Australian Register, 1870).

A vital element for Goyder of reiterating the intention of survey before settlement would be the planting of forest reserves across the country where settlement could be anticipated and where forests could be expected to thrive. Sustainable forestry itself was not a brand new idea in the colonies, including in Victoria where ex-South Australian Ferdinand von Mueller was a professional advocate and activist. But Goyder believed that only legislation and the funding that went with it could secure a sustainable future for forests and the people they served. It was securing the system and resources for forests that was to be the innovation.

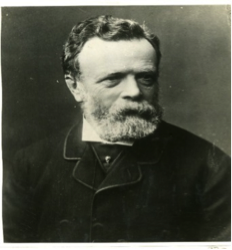

To advance this legislative agenda Goyder enlisted the support of MP Friedrich Krichauff, a botany graduate from Germany and now an experienced South Australian horticulturalist (O’Neill, 1974). Krichauff would lead the charge inside parliament, supported outside by Goyder and Richard Schomburgk, Director of the Botanic Garden (Middelmann, 1976).

Collaboration with these very credible professional advocates was important, and a critical part of the innovative exercise. But Krichauff and Schomburgk would go on to make claims for forestry it could not fulfil. Such claims came directly from their shared German experience. That country had had a long history of felling, before eventual policy changes instituted a program of restoration of their national forests. Both men were great champions of forests and the creation of a system for their sustainable management. But the breadth of their arguments for forests laid the groundwork for the seemingly endless contests that followed the initiatives for legislative change inside parliament.

Krichauff’s style of passionate advocacy was on full display as he introduced a first bill:

in a word, and to speak a bold and noble truth, trees and woods have twice saved the whole world – first by the ark, then by the cross – making full amends for the evil of the fruit tree in Paradise by that which was borne on the tree in Golgotha (SAPD, Sept 6, 1870).

He spoke of the great evil of the past destruction of forests in his homeland. He spoke of the lavish cover of vegetation that had been restored and sustained there since the eighteenth century. He spoke of the huge trade deficit in South Australia which, as Germany had shown, could be corrected by afforestation. And perhaps most contentiously, he spoke of the need to plant extensively in the north so that the rain-inducing qualities of forests could be used to transform the climate of the colony. This climate change would render the land arable and attract the settlers still needed to secure a viable society.

Krichauff’s long, heartfelt homilies offered parliamentarians plenty of ammunition with which to pursue their own arguments for and against the initiative.

One MP was so persuaded of Krichauff’s view that trees caused transformational rainfall that he staunchly opposed a clause for urban forestry. In England, he declared, it ‘was the invariable practice to destroy the trees on the sides of the road’ in order to ‘reduce the rainfall’ (SAPD, Sept 6, 1870). He wanted no part in causing these downpours and flooding in the city and its suburbs!

It was up to Goyder working outside parliament to try and arrest what became a descent into ill-informed dispute. He drafted recurring parliamentary reports, noteworthy for their concision, which studiously avoided the grander claims for forestry – particularly its power to dramatically alter the climate – but reiterated its benefits. His aim was to keep the big picture in the forefront of debate: the practical necessity of planted reserves with, perhaps, some potential to generate export revenue over time (SAPD, Sept 6, 1870).

Critical to this stage of the innovative process were his – and Krichauff’s – emotional and mental stamina. After two years of debate, the frustrating mix of politicians’ argumentativeness and lack of will to act had produced no legislation and no funding for public forests.

In order to keep forestry alive in parliament and the press, Goyder and Krichauff appeared to surrender the bill for a comprehensive scheme of reserves and introduce a more modest measure to incentivize private forestry (Robinson and Johnston, 2001). Alongside the ensuing parliamentary debate Goyder’s Lands Department continued to do what it could within limited resources to quietly advance reserve planting.

By 1873 their untiring collaboration finally produced an act which would see landholders rewarded for planting some of their acreage to forest trees: the ‘Act to encourage the planting of forest trees’. But the idea and modest incentive were never to generate much interest among farmers. The bill’s real value lay in helping to nurture what Krichauff called a ‘forest culture’ amongst colonists. It kept alive the notion of forests and their importance with legislators and the public, not least through the public press, which reported extensively on parliamentary debate.

For Goyder, Krichauff and Schomburgk a sustainable system of public forestry and its management was always both self-evident and urgent, albeit for different reasons. But persuading parliament to this view and to take action on it was made even tougher by the revolving door of politicians and their preference for disagreement over consensus.

Yet Goyder demonstrated the following innovative skills during these first three years of debate:

-his steadfast commitment to forestry as a critical component of a civil and expanding society

-his collaboration with other advocates, however different their understanding of forest and climate science

-the emotional and mental resilience afforded by his constant vision

-the stamina and strategic nous to keep reinventing his approach

Many of these qualities he shared with Krichauff and Schomburgk. The significant difference was the source of their scientific evidence. Each man drew on evidence to make their case. But Krichauff and Schomburgk had drawn on their knowledge of German forests and climate, directly equating the European and Australian environmental contexts. Goyder gathered his instead from unceasing observation in the saddle as he travelled across the South Australian landscapes.

By 1874 the Lands Department had had enough successes and failures for Goyder and Krichauff to try their hand again in parliament. By this time, Goyder was able to circumvent discussion of the first principles of forestry. These were gradually insinuating themselves in colonists’ minds. He headed instead directly to the nuts and bolts of a forest service aimed to secure sustainable and resourced forests. The bill proposed the establishment of a Forest Board to oversee and manage forest reserves and their associated policy (SAPD, July 1,1874).

But Goyder miscalculated. In an effort to stem the tide of debate that had followed the introduction of their first bill, he had his staff draw up a highly detailed operational structure presented as clauses in the bill. He believed that by rendering all of the administrative detail of the structure of the proposed Board would allow for the bill’s expeditious rubber stamping in parliament. But the move backfired in ways reminiscent of Krichauff’s earlier elaborate arguments for forestry. MPs were now eager to discuss the minutiae of administrative detail. Such matters as whether there should be a single, central or decentralized boards; whether or not to remunerate board members, and, if so, how much; whether a board chair was needed, or not; even whether a new ministry was required, occupied ceaseless, inconclusive debates. The self-evident truth of state forestry for Goyder had led him to universalize his view and misjudge the temper of both houses for discussion. Thirteen months later members of both houses remained still in the throes of debate.

By 1875 Goyder and Krichauff may well have anticipated the British wartime PM Clement Attlee’s declaration: ‘Democracy means government by discussion, but it is only effective if you can stop people talking’!

In the end, and on Goyder’s advice, a procedural maneuver was used to suspend the Standing Orders of the House. It forced the bill into legislation and brought an end to all that talking.

Up to this point in the legislative process, environmental innovation was as much about reading, acting and adapting to the combative political and social ecosystem as it was about having any impact on the physical environment.

Regrettably, what had proved a rather tortuous route to date did not change with the advent of the Forest Board. Goyder was to remain on his mettle for the next seven years as Chair of the small group aided, from 1878, by the first Conservator of Forests. And this time things got nasty. The Board comprised five men, including ex-premier Boyle T. Finniss and Schomburgk (Register, November 1875). It was served by John Ednie Brown, appointed from Scotland as Conservator after an exhaustive international search, considered necessary by all but Goyder in order to attract the best available scientific manager (Register, September 1878). He would have preferred the local knowledge of his brother-in-law and nurseryman, Edwin Smith. But forestry was considered too novel in the southern hemisphere to allow for the liability of employing other than a professionally and scientifically trained forester from the north.

Following Brown’s arrival, conflicts became both rife, and very public. Goyder had invited the press to cover Board meetings in order to continue to encourage and sustain the public’s awareness of forestry. This meant that all of their dealings, like parliament’s, were on full display. So while the evolving structure of the Board continued to be problematic, the public interest in forestry was on the rise, helping to secure its place as legitimate public business. Ironically, the increasingly adversarial nature of the Board’s dealings is likely to have fueled rather than dampened that interest.

Internal dispute cycled around three issues:

-the theory that forests planted in the north could transform the colony’s rainfall

-the mixed or single use of forest reserves – for forest trees only or for horticultural activity

-the question of Goyder’s expertise and loyalty to the Board.

Strife began in earnest with Brown’s first annual report to parliament in 1879 (SAPP, 1879). In it he repeated the calls of Krichauff and Schomburgk before him, strongly recommending planting in the far north for the climate change it would bring which would in turn dramatically alter the land use of the region. In addition he wanted an immediate increase in the number of reserves, and their planting exclusively with forest trees. All members, except Goyder, who was absent from the Chair at the time of the meeting, agreed (SAPP, 1879). Goyder was out-voted, and the report sent to parliament.

As Chair of the Board, and because of the grave errors of judgement he believed the recommendations contained, Goyder had little choice but to draft an appendix outlining his objections. In its wording he did his best to be conciliatory, conceding the less far-reaching, but real potential of forests to influence climate and soil. He acknowledged that they were able to provide shelter, increase humidity and condensation, purify the atmosphere, produce springs, contribute fertilizing qualities and subdue acidity. But he unequivocally dissented from the view that forests caused the rain to fall in vast quantities, thereby rendering large tracts of land arable (SAPP, 1879).

Goyder knew that he could not depend entirely on his growing esteem as a highly capable public servant as his only tool for argument. He lacked the scientific credentials of the internationally trained Conservator at a time when the esteem of science was rapidly on the rise (Appleby, Hunt and Jacob, 1994). So he quoted Europe’s top scientists to give voice to his views. The British Association of Engineers and Alexander von Humboldt were cited to argue his view that the maintenance or removal of forests was a matter of balance and compensation. They believed in the principle, said Goyder, that wherever the progress of population settlement required that every ‘portion of the soil be made to yield its quota of human food’, the destruction of forests was demanded. But there were likely to be places in every country where the ‘tide of population can never flow’ and where a forest could flourish and should. So that, where human exigencies, ‘whether for subsistence or health’ required the destruction of forests let them be destroyed but ‘where neither health nor life is concerned then let a wise system of preservation be introduced and acted upon’ (SAPP, 1879).

On the face of it, this quote may sound like an assertion of man’s proper dominion over nature. But, in this context, Goyder’s intention was to correct Brown’s assertion that the country needed to be extensively, and at times, indiscriminately planted to forest. In this Brown was asserting the propriety of forests’ dominion over competing human needs. Goyder’s first principle for the innovation of sustainable forestry was finding the appropriate balance between human and non-human nature. Goyder knew that the claims made for allocation of large swathes of public land for public forests ignored the competing need for production of other essential resources, like food crops and stock grazing, on the same land. An emerging agricultural economy required that a mixed use approach be taken to reserve land. Land for small scale horticulture would be leased to settlers to grow fruit and vegetables for the market. Brown objected strongly to this principle and other Board members came to agree with him.

From the appointment of Brown, Finniss began actively undermining Goyder’s credibility in denigrating letters to the press. One praised the unquestionable expertise of Brown, his ‘eminent qualifications and great experience’, while accusing the government of foolishly treating Goyder as ‘a universal genius, not simply a surveyor’, of encouraging a view of him as ‘a master of the sciences of hydraulic and marine engineering, mineralogy, and geology, and other subjects requiring knowledge, experience, and patient toil to be thoroughly acquainted with’. It was therefore no wonder, said Finniss, that in ‘so simple a matter as forest culture, Mr. Goyder should consider himself wiser than the conservator of forests himself’. Finniss was adamant that ‘we must not place any value on beliefs and opinions which do not emanate from scientific men’ (South Australian Weekly Chronicle, 1882).

Under increasingly severe internal pressure the Board finally imploded in early 1882. The mixed use of forests proved to be the catalyst. Goyder wanted horticulturalists to have access to reserve land to grow fruits and vegetables to feed regional populations, reduce fire risk and sustain that component of the economy. The rest of the Board wanted reserves occupied exclusively by forest trees (South Australian Advertiser, 1882). When the Attorney General’s unequivocally supported Goyder’s position it was the last straw for Board members. They all promptly resigned, except Schomburgk, who was restrained from doing so by his position as a public servant.

Yet, in this apparent setback for forestry, Goyder saw opportunity. He had personally ensured the Board’s work was highly visible for its 7 year life through regular press coverage. As a consequence, forestry had now become an embedded part of public discussion and an accepted part of public business. Goyder was finally able to establish what he had wanted from the outset: a dedicated Woods and Forest Department that would enact a sustainable system of forestry supported by a sustainable organization for its administration.

This story of the innovation of the first forest service in Australia and the British Commonwealth is of the kind Einstein spoke of: a slow and deliberate sticking with a problem until its resolution is achieved. It is a story of the hard slog of Goyder and his collaborators, framed and sustained by a social vision he declared in that first report to parliament in 1870. It is a story of holding fast to a practical environmental policy, developed using his well-honed local environmental literacy. Perhaps most importantly, it is a story of strategically adapting and reiterating the science of forestry and its management in an Australian environment until it finally settled into political and public consciousness. It is a story that has resonance with our contemporary climate debates.

Goyder stands out amongst forestry’s champions in this story in several ways. He did not make excessive claims for forests; he stuck to the empirical knowledge of his environment that was true to his application of the scientific method; he used the same scientific method to make meaning of his political, social and organizational environments, which he knew ultimately controlled the outcomes for the natural environment; and he did not personalize differences of professional opinion. Forestry, not his ego, was his first concern. He showed remarkable patience, perseverance and opportunism in furthering a vision of forestry as an integral, structural component of a civil society. Others by contrast saw and acted on parts of the whole.

How had Goyder learned to read his intersecting environments so effectively and why should that matter to us today?

Enabling innovation for sustainable forestry: Goyder’s education

Janis Sheldrick, Goyder’s biographer, declared that

it does not take any great leap of the imagination to see the unfailing curiosity that George Goyder displayed toward the environment of South Australia as the outcome of the method of his early education (Sheldrick, 2013).

Looking closely at Goyder’s early education does indeed provide a powerful insight into his success as an innovator. It also points to how those same educational principles have contemporary application to the education of our current generation of environmental innovators.

Goyder was in fact educated using the same method that saved Albert Einstein decades later from becoming a high school dropout. They each attended Pestalozzi schools, which Einstein later credited for unlocking his keen desire and ability to see, understand and make a profound difference in the world (Isaacson, 2007).

Goyder’s parents, David and Sarah, were both trained Pestalozzian teachers. And David became a prominent advocate of the method, facilitating the establishment of Pestalozzi schools throughout Great Britain.

Johann Pestalozzi conceived his educational method in the wake of the devastating political and social turmoil of the French Revolution. He saw the potential of children’s education to create adult citizens able to create and support sustainable democratic societies. He described his method of learning and teaching as one that employed the learner’s ‘head, heart and hand’. He believed traditional notions of schooling tried foolishly to teach students fragments of information quite detached from their daily experience. Deep knowledge, he believed, was acquired by the teacher’s engagement of all aspects of a child’s intelligence – their rational, emotional and sensual ways of making meaning – and started from the perspective of the child. David Goyder summarized the essence of Pestalozzian principles as follows:

It was the aim of Pestalozzi to combine the powers of the understanding with the will – of thought with affection – and to bring the both into actual existence in life. Hence, his system is one of faith and love, or, in other words, he united the cultivation of heart and understanding with the labor of the hand. His motto in education was -Heart, Head, and Hand. Science he called in as an auxiliary. He contended that what was done for the head alone destroyed the heart; but what was done for the head, through the instrumentality of the heart, preserved both (Goyder, 1857).

Pestalozzi himself saw his primary purpose in teaching as being

to simplify the elements of all human knowledge according to these laws, and to put them into a series of typical examples that shall result in spreading a wide knowledge of Nature, general clearness of the most important ideas in the mind, and vigorous exercises of the chief bodily powers (Pestalozzi, 1898).

More than two centuries later the Council of Europe has revived these educational principles, adopting the name and modernized rationale of Pestalozzi for its innovative program in teacher education. In the words of its educators, the Council believes that

education, which aims at the formation of active citizens, has to supply learners with the competence to learn and to constantly renew skills of accessing and handling information as well as knowledge stocks. It has to teach learners the art of learning – and it has to do it in a way which makes learning a joyful personal enterprise (Huber and Mompoint-Gaillard, 2011).

Furthermore

specialist and subject-specific competences need to be complemented by transversal knowledge, skills and attitudes if we want them to bear fruit for politically, socially, economically and environmentally sustainable, democratic societies in the Europe of today, and above all, tomorrow (Huber and Mompoint-Gaillard, 2011).

Tamath Rainsford, electrical engineer and a 2008 South Australian Young Tall Poppy Scientist, is one of many in the science-trained community calling for an education that goes ‘back to the future’ to educate ‘renaissance scholars’, that is those who can think in wholes as well as parts, who have the skills to envisage the big picture problems and work towards their resolution. ‘Modern-day societal problems’, she declared, ‘have no established disciplinary authority and therefore require generalist approaches. They require the education of specializing generalists’ (Rainsford, 2009).

Goyder is one model of such a specializing generalist, but one whose learned ability to think across disciplinary boundaries was a required outcome of having first envisaged a model of an ideal civil society. This ethical and social vision framed his rational consideration of environmental, and other, problems. His 1870 report to Parliament on planned land distribution, in which he had first recommended the establishment of forest reserves, he placed their establishment within the larger context of an ideal civic settlement. Public land would be used to provide a public resource that would provide renewable resources to enable dispersed settlement of the growing population around a civic center: a township containing the essential facilities to enable the development of a well-informed citizenry. It is little wonder that he named schools as a critical facility for this purpose. This whole vision preceded the parts, including forestry, needed to sustain it. Goyder’s ability to continuously read and act on the parliamentary process, on public engagement, on a mixed and equitable economy, on the true science of the relationship of forests to climate was crucial to realizing the innovation of forestry. He integrated his scientific understanding, his social scientific understanding and a humanist ethic of an ideal civil society in just the way that current commentators describe as an educational necessity.

Goyder was not a scientist, a visionary before his time, a one-off environmental genius. He had learned early, principles that would sustain an adult ability to continuously read and act across multiple environments. His success as an innovator depended finally on a learned ability to integrate and apply his head, heart and hand in all he did. His ways of seeing his environment have lessons for educators, educational policy-makers and citizens alike in tackling today’s complex environmental problems.

References

Appleby, J. Hunt, L. and Jacob, M. (1994) Telling the Truth about History, New York, p29

American National Economic Council. (2015). obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2015/10/21/fact-sheet-white-house-releases-new-strategy-american-innovation accessed May 2016.

Australian Public Service Commission (2007). ‘Tackling Wicked Problems: a public policy perspective’, Canberra.

Goyder, D. (1857) My Battle for Life, Ipswich, p114.

Huber, J. & Mompoint-Gaillard, P. (2011) ‘Teacher Education for Change: the theory behind the Council of Europe’s Pestalozzi Programme’, Paris, p20.

Huber, J. & Mompoint-Gaillard, P. (2011), p11.

Hunt, G. (2016). ‘G20 Science, technology and Innovations Ministers’ Meeting – Intervention 1’, speech delivered at the Ministers’ Meeting, Beijing, 4 November 2016.

Isaacson, W. (2007) Einstein: his life and universe, London, p26.

Middelmann, R. (1976). ‘Schomburgk, Moritz Richard (1811-1891)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, Canberra.

OECD. (2011). https://www.oecd.org/greengrowth/47445613.pdf, p3, accessed July 2016.

OECD. (2015). www.oecd.org/sti/OECD-Innovation-Strategy-2015-CMIN2015-7.pdf accessed April 2016.

Office of the Chief Scientist (2014). Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics: Australia’s Future, September 2014, p23.

O’Neill, S. (1974) ‘Krichauff, Friedrich (1824-1904), Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, Canberra.

Pestalozzi, J. (1898) How Gertrude Teaches Her Children: An Attempt to Help Mothers to Teach their Own Children, New York, p315.

Rainsford, T. (2009). ‘Back to the Future: Educating the Renaissance Scholar’, unpublished presentation to the Institute for Phototonics, University of Adelaide, 16 September 2009. http://www.adelaide.edu.au/ipas accessed June 2010.

Robinson, R. & Johnston, P. (2001). ‘Forestry in South Australia’ in The Wakefield Companion to South Australian History, Adelaide.

Sheldrick, J. (2013) Nature’s Line: George Goyder, surveyor, environmentalist, visionary, Adelaide, p28.

South Australian Parliamentary Debates (SAPD), Adelaide.

September 6 1870.

September 7 1870.

July 1 1874

South Australian Parliamentary Papers (SAPP). (1879). ‘Annual Report of The Forest Board’, no. 83.

South Australian Register, Adelaide.

(1870). ‘Mr. Goyder’s Report on the Victorian Land Act’, 28 April 1870, p5a.

(1875). ‘The Government Gazette: The Forest Board’, Register, 13 November 1875, p7a .

(1878). ‘Forest Board: Annual Meeting’, 17 September 1878, p1a

South Australian Weekly Chronicle. (1882). ‘Influence of Forests on Rainfall’, 25 February 1882, Adelaide, p22a.

The South Australian Advertiser. (1882). 14 February 1882, Adelaide, p4a.

Tyrrell, I. (1999). True Gardens of the Gods: Californian-Australian Environmental Reform, 1860-1930, Berkeley ; Husmann, J. (2004). ‘Transplantations: A comparative history of afforestation in Nebraska and South Australia, 1870s–1940s’, ETD collection for University of Nebraska – Lincoln. Paper AAI3147142.

Lizzie has worked in Australian international higher education programs and policy with a focus on cross-cultural education. She has a Masters degree in women’s educational leadership and a PhD in leadership education for environmental sustainability from the University of Melbourne, Australia. She is currently developing a comparative case study of the early education of Theodore Roosevelt, Gifford Pinchot and George Goyder.

Lizzie has worked in Australian international higher education programs and policy with a focus on cross-cultural education. She has a Masters degree in women’s educational leadership and a PhD in leadership education for environmental sustainability from the University of Melbourne, Australia. She is currently developing a comparative case study of the early education of Theodore Roosevelt, Gifford Pinchot and George Goyder.