Upholding the sovereignty of diverse knowledges by supporting Indigenous science in high-impact education

Link to the JSE March 2024 General Issue Table of Contents

Fontana JSE March 2024 General Issue PDF

Abstract: The Keepers of the Flame Initiative, now in its fifth year, is a dynamic partnership between cultural fire practitioners, UC Davis faculty, and a diverse study body. This experiential learning initiative at the University of California, Davis centers Indigenous Fire Workshops, focusing on cultural fire. By centering Indigenous science and teaching approaches, this initiative inherently becomes high impact. High Impact Practices (HIPs) are pivotal educational interventions that promote holistic student development and experiential learning. These practices encompass features such as setting appropriately high expectations, experiences with diverse people and circumstances, sustained student engagement over an extended period, meaningful interaction with faculty and peers, public demonstration of learning, real-world relevance of classroom learning, and structured opportunities for reflection. The Keepers of the Flame Initiative incorporates two types of powerful high impact practices: collaborative group projects and community-based learning. These educational practices significantly enrich student learning and particularly benefit historically underserved students as well as broader student populations. I analyze HIP features within the Keepers of the Flame Initiative using survey data gathered in winter 2023, while also delving into the importance of Indigenous-led educational approaches. Indigenous perspectives and educators are crucial in broadening educational approaches, providing a pathway to uphold the sovereignty of diverse knowledge systems, and nurturing a sense of responsibility towards land stewardship and environmental justice.

Keywords: cultural burning, high impact practice, Keepers of the Flame, diverse knowledges, land-as-first teacher, talking circles, community-based learning, collaborative learning

Introduction

What is the role of education in mitigating wildfire risk across the U.S.?

Throughout the United States, the escalating impacts of climate change are amplifying the frequency, scale, and intensity of wildfires due to increased drought and temperature (Westerling, 2016; USGCRP, 2018), particularly in the western region of the U.S. California is unique, with its diverse fire-adapted landscapes. Research shows that before 1800, about 4.5 million acres of the state burned annually (Stephens et al., 2007), with a significant portion attributed to controlled burns conducted by California Native Americans. In contrast, the year 2020 witnessed high-severity wildfires scorching over 4.3 million acres in California alone. The socio-ecological impacts of intentional burning across 4 million acres significantly differ from those of a high-severity wildfire covering the same area. The absence of controlled fire, such as cultural burning and prescribed burning, plays a crucial role in the ecological degradation and the surge of severe wildfires observed in ecosystems worldwide.

For millennia, Indigenous Peoples worldwide have burned landscapes–and continue to burn– as a stewardship practice. California Native communities consider their cultures to be fire-dependent and cultural burn practitioners around the state have used mixed-intensity, controlled fire to actively manage landscapes, habitats, and species for various reasons. These reasons include controlling insects and disease, regenerating native plants, enhancing water use efficiency, creating wildlife habitats, providing community protection from high-severity wildfires, and stewarding culturally important species used for medicine and textiles (Anderson, 2005). Cultural burning is done to maintain and restore resources for traditional Indigenous practices for future generations (Goode et al., 2022). Additionally, Indigenous understandings of fire ecology are intimately linked to ceremonial practices, sustenance economies, and family adaptive strategies (Lake, 2013). In essence, reciprocity governs cultural burning, where cultural practice fosters ecological health, and in turn, a healthy ecosystem provides the necessary materials to sustain cultural practices. This interdependence underscores the inseparable bond between cultural practice and ecosystem well-being.

In the early 18th century, government agencies violently disrupted Indigenous land stewardship practices; through forced removal and relocation; they made fire illegal, actively suppressing it with a militant approach to wildfire management (Vinyeta, 2022). With colonization, cultural burning practices were drastically reduced or eliminated. Consequently, not only were Indigenous cultures suppressed, but ecologically, colonial models of forest management greatly affected fuel accumulation, and increased fire intensity across the state (Norgaard, 2019). Ecosystems reliant on the cultural fire regime have deteriorated over the last century (Long et al., 2017). Many Tribes across the U.S. assert that sovereignty and land stewardship, including cultural burning, are deeply connected with upholding culture including ceremonies, language, medicine, community, economy, dance, governance, art, and song. Sovereignty fundamentally entails the right to exercise self-governance, encompassing the capacity to do so (Kalt and Singer, 2004). Revitalizing Indigenous-led cultural burning on ancestral lands and territories across the state is imperative to mitigate eco-cultural risks and uphold Indigenous sovereignty.

In recent years, California has implemented policy measures aimed at expanding both prescribed and cultural burning capabilities across the state, with a focus on addressing concerns related to liability and Tribal engagement. In late September of 2021, bill AB-642 was enacted, recognizing the importance of increasing the scale and pace of prescribed and cultural burning. The bill mandates the Department of Forestry and Fire Protection to actively engage with California Native American tribes, tribal organizations, and cultural fire practitioners (Dodd, 2021). The legislation includes provisions for appointing a Cultural Burning liaison to enhance efforts to restore fire processes and cultural burning. Furthermore, it provides clear definitions for the terms “cultural burn” and “cultural fire practitioner”, granting cultural burners the same standing as burn bosses. Approximately a week later, SB-332 was passed, focusing on civil liability, and providing legal protections for those conducting burns for public benefit. This bill raises the legal standard for seeking state suppression costs, requiring a demonstration of gross negligence on controlled burn bosses and cultural fire practitioners rather than simple negligence. This bill provides additional exemptions for cultural fire practitioners, relieving them from specific requirements necessary to meet baseline liability standards when they have approval from a Native American tribe or written permission from a landowner to carry out burning activities (Choy, 2021). A more recent legislation, SB 310, introduced to the California Senate in February 2023, authorizes the Secretary of the Natural Resources Agency to enter agreements with federally recognized California Native American tribes. This legislation also modifies permitting requirements for cultural burn practitioners, allowing permits to be issued by tribal governments to tribal members, ultimately increasing accessibility for federally recognized Tribes. While these policy initiatives are beginning to address socio-ecological needs of the region, the crucial question remains: who will be responsible for implementing this timely work?

Higher education institutions can serve as vital bridges between workforce training opportunities and students. The ecological challenges in each U.S. region inform distinct workforce development strategies. Currently, California grapples with an ecological state of fire deficit, necessitating increased prescribed and cultural burning to mitigate the impacts of wildfire severity (CA Wildfire and Forest Resilience Task Force, 2022). Surveyed fire managers have identified increasing the availability and quantity of wildland fire crews, as well as hiring personnel for burn implementation, among their top priorities (Marks-Block and Tripp, 2021). To effectively implement beneficial fire practices, we require a diverse workforce, including wildland fire crews, scientists, educators, civil servants, community engagement coordinators, natural resource managers, cultural fire practitioners, Tribal communities, policymakers, and data specialists. Education, particularly courses engaging with prescribed and cultural burning practitioners, policymakers, and experts, plays a crucial role in bridging gaps between workforce and policy implementation. The Keepers of the Flame course not only addresses disciplinary and educational voids but also prioritizes Indigenous science, thereby fostering high impact practices.

The Importance of High Impact Practices in Higher Education and Workforce Development

Many campuses have courses incorporating experiential learning, active learning, or high impact practices (HIPs). Understanding the effects of these practices on persistence and graduation rates is particularly crucial for transfer students, (Zilvinskis & Dumford, 2018) first-generation students, and students of color (Finley & McNair, 2013). Coined by George Kuh in 2006, the term “high impact practice” encompasses 11 practices, often used interchangeably with terms like experiential learning and active learning. These practices include first year seminars, common intellectual experiences, learning communities, writing intensive courses, collaborative assignments/projects, undergraduate research, diversity/global learning, ePortfolio, service learning/community-based learning, internships, and capstone courses/projects (Kuh, 2018). Over the last two decades, research has consistently shown that high impact practices benefit students in a variety of ways, including perceived greater gains in learning (Finley and McNair, 2013) skill development in critical thinking (Brower and Inkelas, 2010), analytical and problem solving (Laursen, Seymour, and Hunter, 2012; Weiler et al., 2013), higher GPAs and improved writing skills (Vogelgesang and Astin, 2000), as well as enhanced group collaboration skills (Lopatto, 2010) – all crucial for success in the workplace and beyond.

High impact practices share common features that foster active engagement among students and faculty. Common characteristics include: 1) performance expectations are set at appropriately high levels, 2) significant student investment of concentrated effort over a period of time, 3) substantive interactions with peers and faculty, 4) experiences with diversity, where students are exposed to and must face circumstances and people that differ from those students are familiar with, 5) constructive, timely and frequent feedback, 6) opportunities to discover relevance of learning in real-world applications, 7) public demonstration of competence and 8) structured, periodic opportunities to reflect and integrate learning (Kuh, 2018). These practices typically extend beyond the classroom, encouraging collaborative efforts where students take ownership of their learning experiences, and faculty assume coaching and mentoring roles.

Participation in HIPs is associated with higher retention rates (O’Donnell et al., 2015), motivated commitment to civic engagement and social justice (Roffee and Burns, 2020; Weiler et al., 2013), closer relationships with professors (Laursen, Seymour, and Hunter, 2012), more opportunities for mentorship and professionalization (Lindsey, Dowd, and Yu, 2010), aand increased post graduate job prospects (Miller, Rocconi, and Dumford, 2018). The cumulative impact of exposure to multiple HIPs leads to greater beneficial outcomes as participation increases (Finley and McNair, 2013; Hansen and Schmidt, 2017; O’Donnell et al., 2015). Underserved students may experience a compensatory effect, receiving greater benefits compared to traditionally advantaged counterparts (Kuh, 2018; Kuh et al., 2007; Lopatto, 2010; Nagda et al., 1998; O’Donnell et al., 2015). However, as highlighted by Greenman et al. (2021), underserved students often disproportionately face barriers limiting their access to HIPs. These barriers include competing priorities, inadequate guidance on the existence and relevance of HIPs, financial and time constraints (Finley and McNair, 2013), as well as issues such as access to needed transportation, familial complications, major requirements, athletics, and a lack of research opportunities (Coker and Porter, 2015). Strategies to enhance equity in HIPs involve tailoring them to broaden participation, integrating HIPs into the core curriculum through student requirements, and providing additional resources for students, staff, and faculty (Greenman et al., 2021).

High impact practices (HIPs) can offer a competitive edge to institutions, especially in an era when many higher education institutions grapple with enrollment challenges (Vaz, 2019). As an educator, integrating HIPs is linked to positive impacts on learning and persistence outcomes. Educational experiences that engage students through hands-on practice are essential for fostering meaningful, integrated learning over an extended period. These practices benefit students from historically underserved populations and contribute to shrinking the perceived size of the institution through intentional relationship-building both inside and outside of the classroom (Kuh and Kinzie, 2018). As educators, we have the power to shape not only the academic journey of our students but also share the responsibility to center their persistence, engagement, and success.

The Keepers of the Flame Initiative

The Keepers of the Flame: Native American cultural burning and land stewardship in California (commonly shortened to the Keepers of the Flame initiative) is an on-going educational collaboration, and upper-division course at the University of California, Davis. It involves community organizations, several California Indian Tribal communities, cultural burn fire practitioners, and an interdisciplinary team of faculty, graduate students, and undergraduate students. Originating from discussions with Dr. Beth Rose Middleton Manning and graduate students at the time, Chris Adlam, Deniss Martinez and Melinda Adams (Adlam et al., 2022), this initiative is rooted in cross-cultural relationship-building and relationship-nurturing. Honorable North Fork Chairman, Ron Goode and Diana Almendariz (Maidu/Wintun/Hupa/Yurok) have collaborated with Manning for over a decade on various projects and serve as pivotal educators in the course (Manning, 2023). Inspired by the work of Kirkness and Barnhardt on Indigenous student needs in higher education, Keepers of the Flame prioritizes respect, relevance, reciprocity, and responsibility (1991). A key component of the course is to delve into the impact of settler colonialism in contemporary environmental policies, particularly wildfire management, while emphasizing Indigenous cultural burning as a decolonization effort (Tuck, McKenzie, and McCoy, 2014; Manning, 2023). Since 2019, this initiative has evolved to meet the needs of students, California Indian tribal communities, and fire practitioners, and has expanded to include broader community involvement through educational cultural burning workshops. Despite layered challenges posed by COVID-19, this initiative successfully adapted by embracing the approach of learning from the land-as-first-teacher (Archibald, 2008; Styres, 2011).

The course comprises both formative assessments, like weekly discussion posts, and summative assessments such as group projects. Weekly lectures feature diverse guest speakers, including cultural burn practitioners, Indigenous academics, fire policy experts from state and federal agencies, Tribal nonprofit organizations, and graduate students. Cultural burning workshops are central to the course, offering immersive learning opportunities that bring together students, Native community members, cultural practitioners, policy experts, prescribed fire practitioners and others. These workshops primarily occur in two locations: Mariposa, California, led by Chairman Goode, and the Tending and Gathering Garden (Cache Creek Conservancy Preserve, Patwin/Southern Wintun lands) in Woodland, California led by cultural practitioner, Diana Almendariz. The Mariposa site, an 8,000+ year old Miwok village, serves as an active space for local Native cultural practitioners and weavers, offering students the opportunity to camp for three to four days. Participation in these workshops is broad, encompassing students, and faculty from various universities, state and federal agencies, non-profit organizations, as well as tribal leaders from diverse Native communities, with attendance ranging from 30 to over 100 attendees (Figure 1).

The Tending and Gathering Garden, located at Cache Creek Conservancy, has a complex history of land use, including gravel mining and recent efforts in habitat restoration and environmental education. Over the past two decades, Native women elders, and basket weavers have stewarded this garden, offering educational insights into culturally important species like redbud, tule, dogbane, deergrass, and their relationships with fire (Adams, 2023). Students visit the Garden at least three times during the quarter, usually on Sunday afternoons. During these field days, students prepare the land for cultural burning as well as gain insights into the impacts of colonial (mis)management on the land. Under the guidance of Diana Almendariz, participants engage in activities such as selective thinning, raking, and learning about culturally important species, their specific phenological cues as well as the importance of culture and language. At least one cultural burn takes place at the Conservancy each quarter, which has more recently evolved into a public-facing workshop that brings together multiple Tribal communities, state and federal agencies, and nonprofit conservation organizations. These hands-on educational experiences facilitate intergenerational learning, networking, and workforce capacity building, fostering relationships with the land and broader community (Figure 2). As a result, these workshops are central to the Keepers of the Flame course.

Figure 1. Mariposa cultural burning workshops. A – burning sourberry (Rhus aromatica) into the evening. B – burning sourberry (Rhus aromatica) during the day. (Photos taken by N. Fontana)

Figure 2. Field days at the Tending and Gathering Garden (TGG). A – fresh burning of tlaka (in Wintun)/tule (Schoenoplectus acutus). B – burning collie (in Wintun)/dogbane (Apocynum cannabinum) with Diana Almendariz. C – fresh tlaka/tule shoots after a burn. D – the beginning of a talking circle with Diana. (Photos taken by N. Fontana)

Methods

The Keepers of the Flame initiative takes place during the academic winter quarters, spanning from January to March, aligning with California’s current ecological conditions for prescribed burning. This timing also allows for safe burn windows conducive to cultural burning practices. Understanding how to implement cultural burns across various jurisdictions, considering liability and permitting procedures, is crucial. Equally important is having partners with land access and policy knowledge about burning on the land. As a current member of the teaching team (since 2021), I submitted an IRB letter of determination to the UC Davis IRB Office and received a determination of “Not Human Subject Research.” To assess the impact of high impact practices and their features in the Keepers of the Flame initiative, I distributed an online survey to 19 students from the winter 2022 cohort, one year after their participation in the course. Students received the survey link in early January 2023, and responses were collected throughout February 2023. Of the 19 students, 15 responded to the survey. Student responses were anonymized. The class comprised a mix of undergraduate and graduate students. The survey consisted of sixteen questions: three open-ended questions, one check-box question, one ranking question and eleven Likert-style survey questions.

Results

Three open-ended questions assessed knowledge acquisition and learning processes, prioritizing qualitative insights over direct self-reported evidence of high impact practices within the course. While the three open-ended questions remain less explored in this analysis, responses to thirteen questions will be thoroughly examined, including a check-box question, ranking question and eleven Likert-style survey questions. For instance, students were asked to rank the learning activities most impactful for their understanding of cultural burning, including options such as “cultural burn workshops in Mariposa”, “field days at the TGG”, “lectures by community members, scientists and policy makers”, “discussion posts”, and “group project”. The percentage of students attributing impact to learning activities varied, with cultural burn workshops receiving the highest rating at 80%, followed by TGG field days at 60%, lectures at 47%, group projects at 13% and discussion posts at 7%. Additionally, students were invited to provide open-ended responses explaining their rankings. Below, I highlight a few student responses.

I feel like all the activities of the class complement each other very well so it was difficult to rank them on impact. I personally ranked in-person hands-on activities higher because my experiences bonding with my classmates and seeing Native leaders conduct cultural fire work in the field was so extraordinary. From my past experiences, classroom environments can easily create a gap between learners and the subject matter of the course. – Student A

This class is unique in how it’s structured. I’ve never had a class with this many hands-on components! Which meant that the more typical aspects of the class (project and posts) fell flat compared to the fieldwork and burn days. – Student B

The cultural burn workshop in Mariposa was definitely the most impactful activity by far. Being able to spend multiple days there and engaging in a variety of activities, whether it be helping with the burns, preparing weaving materials, and searching for redbud and other basket materials, really made a huge impact on my experience. Also spending a significant amount of time learning from all the people there during the morning talking circles and around the bonfires really taught me so much more than just a lecture or one day spent in the field together could. – Student C

One checkbox question asked students to select the qualities that distinguished this course from others at the university. The options and corresponding student response are as follows: “Engagement with diverse perspectives/people” (100%), “Interactions with community members” (93%) , “Field experiences” (93%), “Out of the classroom peer-to-peer interactions” (73%), and “This class was not unique. Other classes also included many of these qualities.” (0%). Notedly, all student respondents expressed that this course had engagement with diverse perspectives and people. Ten survey questions were developed to evaluate the presence of eight HIP features in the Keepers of the Flame initiative. As mentioned in the introduction, these features include appropriately high expectations, experiences with new circumstances and diverse people (2 questions), significant time investment, meaningful interactions with faculty, community members and peers, public demonstration of competence, opportunities to learn through real-world applications (2 questions), and periodic structured opportunities to reflect and integrate learning (Table 1). Likert survey responses were limited to five options measuring the level of agreeability – “Strongly agree”, “agree”, “neutral”, “disagree”, and “strongly disagree.” Figure 3 shows the Likert scale chart analysis of student responses (n=15). (Survey statements are abbreviated in the chart analysis due to space limitations).

Table 1. High-impact practice features aligned with survey statements, rated on a Likert scale of agreeability.

Figure 3. Likert scale chart displaying student survey responses regarding the presence of high-impact practice features in the Keepers of the Flame Winter 2022 cohort.

Discussion

High Impact Practices in the Keepers of the Flame Initiative

In the Keepers of the Flame initiative, two evident high impact practices are apparent: collaborative assignments in the form of final group projects and community-based learning opportunities, exemplified by field days at the Tending and Gathering Garden (TGG) and cultural burn workshops in Mariposa. These practices correspond with two of the 11 recognized high impact practices outlined by Kuh (2008). This is particularly significant because historically underrepresented or underserved students who engage in one or more high impact practices reported greater gains in learning outcomes compared to their peers who are involved in only one high-impact practice (Finley and McNair, 2013).

Students engage in a group project where they create a video or a podcast focusing on cultural burning issues. These projects are shared with guest speakers, cultural burning practitioners and partners. The objectives of the project are threefold: firstly, to deepen understanding of fire and cultural burning issues in California; secondly, to develop a product that acknowledges practitioners’ contributions; and thirdly, to contribute to cultural burning revitalization through outreach, education, knowledge generation and advocacy for reform. The group projects offer students the opportunity to publicly demonstrate their learning to their peers, cultural burn practitioners and broader community. Through collaborative learning, students acquire transferable job skills such as teamwork, problem-solving, written, and oral communication, inquiry, and analysis as well as critical and creative thinking. Importantly, students create a new resource (podcast or video) for cultural burning community partners for their use (Manning, 2023). Partners have presented these resources during larger community meetings to share knowledge and showcase community initiatives aimed at enhancing cultural burning capacity.

As previously noted, cultural burn workshops and TGG field days unite diverse community members with students, fostering Indigenous-led community-based learning opportunities. These experiential learning activities directly engage students with topics discussed in lectures, readings, and classroom discussions, enabling them to address real-world challenges (Kuh et al., 2017). Immersing themselves on the land and the cyclical, sensory aspects of cultural burning, allows students to imbue their learning with meaning and context, as mentioned by Student C.

…Being able to spend multiple days there [Mariposa] and engaging in a variety of activities, whether it be helping with the burns, preparing weaving materials, and searching for redbud and other basket materials, really made a huge impact on my experience. Also spending a significant amount of time learning from all the people there during the morning talking circles and around the bonfires really taught me so much more than just a lecture or one day spent in the field together could.

This deep learning requires time and involves extensive discussions with peers, community members, and experts, especially Native elders, and leaders. Engaging in activities like searching for basketry materials and preparing weaving materials alongside Native elders, aids students in understanding the rationale behind burning, and the cultural significance of the practice. More importantly, it creates an opportunity to build relationships and connect with community. Consequently, many students reflect on the impact of field days and cultural burn workshops throughout the course and in discussion posts. Community-based learning is at the core of the Keepers of the Flame, seamlessly blending community engagement with instruction and reflection. When combined with formative assessments, like discussions, which encourage self-reflection, community-based learning enriches the learning process with an emphasis on iterative and reciprocal learning. Reciprocal learning empowers students to co-create knowledge by collaborating with each other, learning together and then applying this newly acquired knowledge (Love et al., 2021; Lubatkin et al., 2001) Lastly, students are encouraged to extend their engagement beyond the course itself. Upon completion, they are invited to join the Keepers of the Flame listserv for ongoing community connections, and to learn about upcoming cultural burning opportunities, and advancements in research. Many alumni of the Keepers of the Flame class continue to actively engage in cultural burning workshops and pursue related research projects. Current student research projects include exploring the impacts of diverse cultural burning practices on soil health and culturally important species.

Features of High Impact Practices in the Keepers of the Flame Initiative

Analyzing Figure 3, four prominent features of high impact practice emerge among student respondents (marked as “strongly agree”). These include: “opportunities to discover relevance of learning through real-world applications” (93%), “periodic, structured opportunities to reflect and integrate learning” (93%), “interactions with faculty and peers about substantive matters” (87%), “experiences with diversity, wherein students are exposed to and must contend with people and circumstances that differ from those which students are familiar” (87%). While students felt that they had periodic structured opportunities to integrate learning (93%), receiving timely, frequent, and constructive feedback on assignments was less evident (47%). This student feedback provides valuable and constructive information for instructors to improve in assessment frequency and further refine assessment methods in future iterations of the course. Only 40% of students strongly agreed that they invested a significant amount of time and effort into their group project, while the remaining 60% agreed. Nonetheless, 73% strongly valued the opportunity to share their group project in a public presentation.

Experiential learning activities, such as cultural burn workshops and field days at the Tending and Gathering Garden, invite students to test and ground classroom learning through real-world applications by participating in Native-led cultural burns. When asked to identify the most impactful learning activities, students ranked cultural burn workshops highest at 80%, followed by TGG field days at 60%, lectures at 47%, group projects at 13% and discussion posts at 7%. In both classroom and field settings, group project planning and discussions offer students structured opportunities to reflect and integrate their learning. As stated by a student respondent, “The group projects and discussion posts were helpful to put all the ideas and concepts that were received at the workshops and applied to more directly in the classroom.” These environments also foster interactions with faculty, peers, and community members, exposing students to diverse perspectives and circumstances.

As seen in Table 2, the learning activities that were most impactful also had multiple high impact practice features present. Cultural burn workshops and field days at the TGG serve as community-based learning experiences, representing a type of high impact practice. They embody four key features of high impact practices: significant time investment, meaningful interactions with faculty and peers, opportunities to discover relevance of learning through real-world applications, and experiences with diversity. As a result, the deep learning impact of this community-based learning is reflected in responses gathered from the surveys. As stated by a student,

This class is definitely unique in that the field trips to the TGG and Mariposa made it easier to connect not only with the content, but also the cultures and people who continue to build the knowledge in such courses. By practicing cultural fire alongside seasoned professionals, I learned more through observation and hands-on work than I could through readings and lectures alone.

The group project had two high impact practice features including significant time investment, and public demonstration of learning. Finally, the discussion posts had periodic, structured opportunities to reflect learning and experiences with diversity, while guest lectures provided students with a diversity of voices. Students learn by doing, listening, and observing on different lands, which offer insights into land histories and the colonial impacts of (mis)management on Native lands. For example, burning practices at the Tending and Gathering Garden differ substantially from those in Mariposa in terms of Native leadership and communities, ecologies, burn intensities, weather conditions, burn types, burn scales, culturally important species, cultural outcomes, among many other factors. As one student stated, “Diverse communities have even more diverse goals. Within the context of burning, people burn for many resources, and the act of (organizing) a burn is a great way to build community regionally.” A crucial insight gained by students is witnessing the diversity of cultural burning practices, which are as varied as the ecosystems and Indigenous communities they serve.

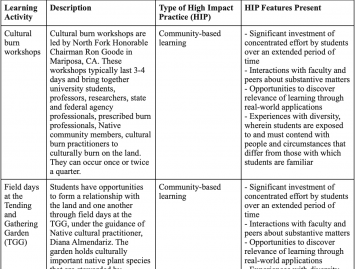

Table 2. Keepers of the Flame learning activities, their descriptions, type of high impact practice (HIP), and HIP features present within each learning activity.

Indigenous Pedagogies as High Impact Education

It’s late February at the Cache Creek Conservancy in Winters California, so there is a crispness in the air. I can hear the cars rolling across the gravel road as folks enter the Conservancy early on a Sunday morning. Students are dressed in outdoor work clothes, beanies, gloves as they wander through the parking lot. Diana stands in the wooden gazebo and gently waves for people to come towards her. As is common in small gatherings, a circle naturally forms as people huddle for both warmth and as familiarity grows in conversation. As more people join, you can hear some ripples of laughter and the circle grows warmer. There’s a moment when it appears that everyone has arrived and Diana projects her voice so that everyone can hear her. She says, “Welcome everyone! Welcome to the land. My name is Diana…I’d like to go around and have everyone introduce themselves and where they are from. Think about why you are here. What do you hope to learn today?” It’s the moment that as an educator you can see some students beaming ready to share while some are a little puzzled and others are quickly mapping out the words they’d say, then crossing them out and rewriting them in the air. Diana shares first in our circle. It’s at this moment when we all become a little more still and begin to listen.

Students learn from diverse Native practitioners across California, exposing them to a spectrum of perspectives and cultural burning practices. Consequently, students encounter Indigenous approaches to teaching and learning, such as talking circles and land-as-first teacher approach (Simpson, 2014; Wildcat et al., 2014). Pedagogical talking circles offer supportive spaces for students to engage in situated relatedness, respectful listening, and reflective witnessing (Barkaskas and Gladwin, 2021), often for the first time. Seventy-three percent of students strongly agreed that “…Spending time in a talking circle, I reflected on my specific lived history and how that informed my perspective, in relation to other people.” In these circles, students reflected on their unique lived experiences and how it shaped their perspectives in relation to others (Figure 2). This allows them to recognize and appreciate a different type of learning outside the normative educational system. This approach challenges some students to intentionally create a space relating, questioning, and listening. As one student expressed,

It is important to step back from what we claim to know and listen to the words which people tell us but also to the sounds of our surroundings. We often get caught up looking for answers that we feel obligated to find something new. Yet much of the information we seek is already around us and has been put into practice for generations.

The most impactful learning activities in the course are those that students find directly applicable to real-world scenarios. Specifically, students find place-based learning with cultural burn practitioners particularly impactful, as it justly addresses the wildfire crisis through Indigenous leadership. Land-as-first-teacher places Indigenous worldview in the center, encompassing “Indigenous understandings of the land, Indigenous language in relation to land, and Indigenous critiques of settler colonialism” (Simpson, 2014; Wildcat et al., 2014; Tuck, McKenzie, and McCoy, 2014). Both Diana Almendariz and Chairman Ron Goode introduce the land to students and community members during the opening circles, grounding spirituality, relationality, and significance in various ways. It presents an opportunity to deconstruct and disrupt colonial ideologies about fire through respectful sharing of Indigenous knowledges and perspectives (Lowan-Trudeau, 2019). As one student expressed,

I really learned about the importance of land stewardship. As an Indigenous person, myself, I already valued this, but learning about California Natives, a unique relationship to wildfire. I learned the importance of advocating for cultural fire keeping rights and the urgency during the climate change we are experiencing to do so!”

While students interact with each other throughout the week, the pivotal experiential aspect of the course occurs when students, guided by Native cultural practitioners, engage directly with the land. This hands-on experience allows them to reflect on and cultivate relationships with fire, themselves, other community members, and the potential for future advocacy.

Indigenous pedagogies inherently embody high-impact learning. The Keepers of the Flame initiative is structured to embrace Native Science, rooted in “perceptive knowledge gained from using the whole body/mind in our senses in direct participation with the natural world” (Cajete, 2018). This holistic approach integrates the entire human experience, fostering collaborative learning and community-based learning, both recognized as high impact practices. Throughout the initiative, all features of high impact practice are present to varying degrees, with an overarching emphasis on experiencing diversity. Students navigate unfamiliar spaces, interact with different people with unique life histories, and engage in diverse learning environments. Ultimately, the Keepers of the Flame initiative centers diverse Indigenous worldviews on fire, promotes respect for diverse knowledge systems, and cultivates a sense of responsibility towards land stewardship and environmental justice.

Conclusion

Centering decolonization efforts involves supporting Indigenous-led environmental initiatives and recognizing that “what schools do not teach may be just as important as what they do,” (Eisner, 2002). Curricula that amplify diverse voices, including those of Indigenous scholars, practitioners, and experts, are crucial to contesting colonialism and oppression inherent in environmental management and higher education. Understanding this historical background is essential for grasping the significance of Indigenous fire education within a predominantly Western educational framework, particularly considering colonial impacts, contemporary environmental trends, and job training, broadly. To get more cultural burning on the ground, we need to educate our future through mindful, respectful Indigenous-led education.

In the past decade, there has been a surge of initiatives led by non-Indigenous educational institutions, land-owning organizations, and government agencies aimed at engaging Indigenous communities to incorporate stewardship principles rooted in Indigenous Traditional Knowledge (ITEK) (Goode et al., 2022; USFS, 2023). It is widely acknowledged that the tools of Western science alone cannot adequately address the impacts of climate change. This recognition is evident even at the federal level, where a memorandum was issued by the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) and the Council of Environmental Quality (CEQ) prioritizing ITEK and centering its inclusion in Federal decision-making in science and policy (2022). However, truly centering Indigenous Knowledge in scientific and policy processes requires not only acknowledging its importance but also elevating Indigenous voices and priorities in the decision-making process. While this sentiment has been consistently expressed and emphasized, the critical question remains: What structural and educational processes can be implemented to provide tangible opportunities for Indigenous voices and allyship to actively participate in decision-making processes?

Education, awareness, and workforce development are scaffolded initiatives advancing Indigenous land stewardship initiatives. Within the realm of education, there exists many opportunities to foster novel learning experiences for students through high impact learning. By imparting knowledge and fostering a sense of interconnectedness with the world, education can inspire student engagement and investment in addressing societal challenges. A fundamental objective of educators should be to impart transferable skills that enable students to pursue fulfilling employment opportunities. However, at many institutions, these skills are often passively acquired or assumed, rather than taught or metacognitively addressed. Consequently, the learning curves for acquiring these skills can vary significantly among students. Critical skills such as time management, networking, critical thinking, adaptability, financial and digital literacy, teamwork, and problem-solving are essential for undergraduate students, yet integrated opportunities within classroom settings to highlight the acquisition of these skills are rare. Assessments may miss the mark of evaluating these process-based skills. By providing metacognitive moments that encourage students to critically reflect on themselves as thinkers and learners, educators can enhance the development of these critical skills that further students’ occupational goals. Moreover, fostering an educational environment that nurtures family and community bonds, intellectual growth, community participation and creativity is paramount for faculty, staff, and students alike at educational institutions (Scobey, 2023).

Today, education is tasked with embracing a holistic approach and purpose, aiming to equip individuals with essential skills for career success while nurturing a community-driven life, rich in meaning. This imperative is particularly important now, as evidenced by a nationwide 8% decline in undergraduate enrollment from 2019 to 2022, as reported by the National Student Clearinghouse (Binkley, 2023). To incentivize higher education pursuits, radical shifts are needed within the U.S. educational system. These shifts include initiatives such as establishing low-cost degree programs, enhancing student support, and advising services, transitioning to competency or outcome-based education models, prioritizing the growth of underrepresented communities in traditional higher education settings, introducing majors and certifications aligned with contemporary job market demands (Levine and Van Pelt, 2021) and promoting evidence-based teaching strategies, notably high impact practices. Education is called to adopt a holistic approach in learning objectives and incorporate metacognitive opportunities within the classroom to support and acknowledge critical job skill development. A growing body of literature underscores the immense value of high impact teaching for both student learning outcomes and job skill training (Kuh et al., 2018). Institutionally, incentivizing faculty adoption of high-impact practices necessitates leveraging mechanisms such as reward systems, work allocation strategies, professional development initiatives, leadership support (Austin, 2011), as well as equitable and expedient payment/reimbursement mechanisms for community partners across contexts.

As recently emphasized by Robin Wall Kimmerer and Kyle Artelle, institutions must ask themselves ‘How can we support Indigenous science’s pivotal role in creating a sustainable future?’ (2024). While institutions increasingly acknowledge the significance of Indigenous perspectives in policy and education, initiatives aimed at integrating knowledge risk sidelining Indigenous voices and priorities. Instead, active centering means prioritizing Indigenous leadership in higher education endeavors like Keepers of the Flame, which in doing so, are high impact by nature. By conscientiously nurturing younger generations of students exposed to a diversity of knowledge systems, we can cultivate pluralism within the workforce, fostering diversity and inclusivity in educational practices that can extend into everyday life and shape the future of our climate.

Acknowledgements

I want to express deep gratitude to elders and practitioners including Diana Almendariz, and Chairman Ron Goode for teaching future generations about what it means to care for the land. I extend heartfelt thanks to other Indigenous elders, teachers, cultural bearers, and practitioners who come and contribute their time, knowledge, energy, and more to these workshops. I am grateful to Pam Gonzalez, Danny Manning, Dirk Charley, Julie Dick-Tex, Florence Dick and Gladys Dick. Special appreciation goes to Beth Rose Middleton Manning, Chris Adlam, Melinda Adams, Deniss Martinez and all the Keepers of the Flame students – present, past, and future.

References

AB 642, Friedman. Wildfires. AB-642, 2019-2020 Reg. Sess. (Cal. 2021)(enacted). https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billNavClient.xhtml?bill_id=202120220AB642.

Adams, M.M. (2023). Indigenous Ecologies: Cultivating Fire, Plants, and Climate Futurity. Artemisia, 49(2), 20-29. https://www.cnps.org/publications/scientific-journal.

Adlam, C., Almendariz, D., Goode, R. W., Martinez, D. J., & Middleton, B. R. (2022). Keepers of the flame: supporting the revitalization of Indigenous cultural burning. Society & Natural Resources, 35(5), 575-590.

Anderson, K. (2005). Tending the wild: Native American knowledge and the management of California’s natural resources. University of California Press.

Archibald, J. A. (2008). Indigenous storywork: Educating the heart, mind, body, and spirit. UBC press.

Austin, A.E. (2011). Promoting evidence-based change in undergraduate science education. In Fourth committee meeting on status, contributions, and future directions of discipline-based education research.

Barkaskas, P., & Gladwin, D. (2021). Pedagogical Talking Circles: Decolonizing Education through Relational Indigenous Frameworks. Journal of Teaching and Learning, 15(1), 20-38.

Binkley, C. (2023). Why more Americans are skipping college. PBS News Hour. Retrieved from https://www.pbs.org/newshour/education/why-more-americans-are-skipping-college.

Brower, A. M., & Inkelas, K. K. (2010). Living-learning programs: One high-impact educational practice we now know a lot about. Liberal Education, 96(2), 36-43.

Cajete, G. (2018). Native science and sustaining Indigenous communities. In M. K. Nelson & D. Shilling (Eds.), Traditional Ecological Knowledge: Learning from Indigenous Practices for Environmental Sustainability (pp. 15–26). Cambridge University Press.

California Wildfire and Forest Resilience Task Force. (2022). California’s strategic plan for expanding the use of beneficial fire. California Wildfire and Forest Resilience Task Force.

Choy, B. (2021, September 16). These two new California bills will help tribes complete prescribed burn projects. Siskiyou Daily News. https://www.siskiyoudaily.com/story/news/2021/09/16/these-two-new-california-bills-help-tribes-complete-prescribed-burn-projects/8363483002/.

Coker, J., & Porter, D. (2015). Maximizing experiential learning for student success. Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning, 47(1), 66–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/00091383.2015.996101.

Eisner, E. (2002). The Educational Imagination: On the Design and Evaluation of School Programs. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill Prentice Hall.

Finley, A., & McNair, T. (2013). Assessing underserved students’ engagement in high-impact practices. Association of American Colleges and Universities. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED582014.pdf.

Goode, R. W., Beard, S. F., & Oraftik, C. (2022). Putting fire on the land: The Indigenous people spoke the language of ecology, and understood the connectedness and relationship between land, water, and fire. Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology, 42(1), 85-95.

Greenman, S. J., Chepp, V., & Burton, S. (2022). High-impact educational practices: leveling the playing field or perpetuating inequity?. Teaching in Higher Education, 27(2), 267-279.

Hansen, M., & Schmidt, L. (2017). The Synergy of and Readiness for High-Impact Practices During the First Year of College. Journal of The First-Year Experience & Students in Transition, 29(1), 57–82. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1139402.

Kalt, J. P., & Singer, J. W. (2004). Myths and realities of tribal sovereignty: The law and economics of Indian self-rule. Available at SSRN 529084.

Kimmerer, R. W., & Artelle, K. A. (2024). Time to support Indigenous science. Science, 383(6680), 243-243.

Kirkness, V. J., & Barnhardt, R. (1991). First Nations and higher education: The four R’s—Respect, relevance, reciprocity, responsibility. Journal of American Indian Education, 1-15.

Kuh, G. D., Kinzie, J., Cruce, T., Shoup, R., & Gonyea, R. M. (2007). Connecting the dots: Multi-faceted analyses of the relationships between student engagement results from the NSSE, and the institutional practices and conditions that foster student success. Indiana University Center for Postsecondary Research.

Kuh, G., O’Donnell, K., & Schneider, C. G. (2017). HIPs at ten. Change: The magazine of higher learning, 49(5), 8-16.

Kuh, G. (2018). Whither holistic student development: It matters more today than ever. Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning, 50(3-4), 52-57.

Kuh, G. D., & Kinzie, J. (2018). What really makes a ‘high-impact’practice high impact. Inside Higher Ed, 1.

Lake, F. K., Wright, V., Morgan, P., McFadzen, M., McWethy, D., & Stevens-Rumann, C. (2017). Returning fire to the land: celebrating traditional knowledge and fire. Journal of Forestry, 115(5), 343-353.

Laursen, S., Seymour, E., & Hunter, A. B. (2012). Learning, teaching and scholarship: Fundamental tensions of undergraduate research. Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning, 44(2), 30-37.

Levine, A., & Van Pelt, S. (2021). The Future of Higher Ed is Occurring at the Margins. Inside Higher Ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/views/2021/10/04/higher-education-should-prepare-five-new-realities-opinion

Lindsey, M., Dowd, A., & Yu, T. (2010). Tapping HSI-STEM Funds to Improve Latina and Latino Access to the STEM Professions. Los Angeles, CA: University of Southern California.

Long, J.W., R.W. Goode, R.J. Gutteriez, J.J. Lackey, and M.K. Anderson. 2017. Managing California Black Oak for tribal ecocultural restoration. Journal of Forestry 115 (5): 426–434.

Lopatto, D. (2010). Science in Solution: The Impact of Undergraduate Research on Student Learning. Washington, D.C.: Council on Undergraduate Research.

Love, H. B., Valdes-Vasquez, R., Olbina, S., Cross, J. E., & Ozbek, M. E. (2022). Is cultivating reciprocal learning the gold standard for high impact pedagogies?. Higher Education Research & Development, 41(4), 1136-1151.

Lowan-Trudeau, G. (2019). From reticence to resistance: Understanding educators’ engagement with indigenous environmental issues in Canada. Environmental Education Research, 25(1), 62-74.

Lubatkin, M., Florin, J., & Lane, P. (2001). Learning together and apart: A model of reciprocal interfirm learning. Human Relations, 54(10), 1353 1382. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/a019198.

Manning, B. R. M. (2023). 8. Relationships, respect, and reciprocity: approaches to learning and teaching about Indigenous cultural burning and landscape stewardship. Environmental Justice, 145.

Marks-Block, T., & Tripp, W. (2021). Facilitating Prescribed Fire in Northern California through Indigenous Governance and Interagency Partnerships. Fire 2021, 4(3), 37. DOI

Miller, A., Rocconi, L., & Dumford, A. (2018). Focus on the Finish Line: Does High-Impact Practice Participation Influence Career Plans and Early Job Attainment? Higher Education, 75(3), 489–506. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-017-0151-z

Nagda, B., Gregerman, S., Jonides, J., von Hippel, W., & Lerner, J. (1998). Undergraduate student-faculty research partnerships affect student retention. The Review of Higher Education, 22(1), 55-72.

Norgaard, K. M. (2019). Salmon and acorns feed our people: Colonialism, nature, and social action. Rutgers University Press.

O’Donnell, K., Botelho, J., Brown, J., Gonzalez, G., & Head, W. (2015). Undergraduate Research and Its Impact on Student Success for Underrepresented Students. New Directions for Higher Education (169), 27–38. https://doi.org/10.1002/he.20120.

Roffee, J. A., & Burns, K. (2020). International Student Mobility & Study Tours as a Tool for Social Justice. Teaching in Higher Education. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2020.1765328.

SB 310, Dodd. Prescribed fire: civil liability: cultural burns. https://openstates.org/ca/bills/20232024/SB310/.

SB 322, Dodd. (2021). Civil liability: prescribed burning operations: gross negligence. https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billTextClient.xhtml?bill_id=202120220SB332.

Scobey, D. (2023). The Paradigm Project: A Call for Radical Renewal of Higher Education. Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning, 55(2), 14-19.

Simpson, J. (2014). Teaching minority Indigenous languages at universities. Indigenous languages: Their value to community, 54-58.

Stephens, S. L., Martin, R. E., & Clinton, N. E. (2007). Prehistoric fire area and emissions from California’s forests, woodlands, shrublands, and grasslands. Forest Ecology and Management, 251(3), 205-216.

Styres, S. D. (2011). Land as first teacher: A philosophical journeying. Reflective Practice, 12(6), 717-731.

The White House. (2022). White House Releases First-of-a-Kind Indigenous Knowledge Guidance for Federal Agencies. Retrieved from https://www.whitehouse.gov/ceq/news-updates/2022/12/01/white-house-releases-first-of-a-kind-indigenous-knowledge-guidance-for-federal-agencies/

Tuck, E., McKenzie, M., & McCoy, K. (2014). Land education: Indigenous, post-colonial, and decolonizing perspectives on place and environmental education research. Environmental Education Research, 20(1), 1–23.

USGCRP (U.S. Global Change Research Program). (2018). Impacts, risks, and adaptation in the United States: Fourth National Climate Assessment, volume II. Reidmiller, D.R., C.W. Avery, D.R. Easterling, K.E. Kunkel, K.L.M. Lewis, T.K. Maycock, and B.C. Stewart (Eds.). Retrieved from https://nca2018.globalchange.gov/downloads. doi:10.7930/NCA4.2018.

Vaz, R. (2019). High-Impact Practices Work. Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved from https://www.insidehighered.com/views/2019/06/04/why-colleges-should-involve-more-students-high.

Vinyeta, K. (2022). Under the guise of science: how the US Forest Service deployed settler colonial and racist logics to advance an unsubstantiated fire suppression agenda. Environmental Sociology, 8(2), 134-148.

Vogelgesang, L. J., & Astin, A. W. (2000). Comparing the effects of community service and service-learning. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, 7(1).

Weiler, L., Haddock, S., Zimmerman, T. S., Krafchick, J., Henry, K., & Rudisill, S. (2013). Benefits derived by college students from mentoring at-risk youth in a service-learning course. American Journal of Community Psychology, 52, 236-248.

Westerling, A. L. (2016). Increasing western US forest wildfire activity: sensitivity to changes in the timing of spring. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 371(1696), 20150178.

Wildcat, M., McDonald, M., Irlbacher-Fox, S., & Coulthard, G. (2014). Learning from the land: Indigenous land based pedagogy and decolonization. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, 3(3).

Zilvinskis, J., & Dumford, A. D. (2018). The relationship between transfer student status, student engagement, and high-impact practice participation. Community College Review, 46(4), 368-387.

Biography: I am a community-engaged ecologist and educator with over 15 years of teaching experience spanning continents, disciplines, and educational stages. I hold a Ph.D. in ecology from the University of California, Davis. My research is focused on centering and nurturing land stewardship practices, especially in today’s context of climate change. My passion lies in effectively bridging research with practice, policy, and education to make a lasting, positive impact. My email contact information is nmfontana (at) ucdavis.edu.

Biography: I am a community-engaged ecologist and educator with over 15 years of teaching experience spanning continents, disciplines, and educational stages. I hold a Ph.D. in ecology from the University of California, Davis. My research is focused on centering and nurturing land stewardship practices, especially in today’s context of climate change. My passion lies in effectively bridging research with practice, policy, and education to make a lasting, positive impact. My email contact information is nmfontana (at) ucdavis.edu.