The Sabils of Cairo: Small Scale Urban Adaptations to Water Stress

Farmer JSE March 2020 Water Issue PDF

Link to JSE March 2020 Water and Climate Issue Table of Contents

The city of Cairo, Egypt, has a long history of charitably endowed water fountains, called sabils,[1] that form an integral part of the urban landscape by offering drinking water to passersby. Caireens and other urban dwellers in the region are facing significant environmental challenges as temperatures rise and already scarce water resources are further stretched in the context of global climate change. Urban residents with lower socioeconomic status face added infrastructural stressors, and many such populations are water insecure. This paper examines the ways in which two local communities in Cairo are modifying their built environment to better serve their needs by drawing on long-standing traditions informed by religious precepts and relations of reciprocity. These ethical frameworks undergird the establishment of small-scale water infrastructure, sabils, that point to possibilities for resilient water practices. Additionally, this paper offers insight into the value of joint faculty-undergraduate ethnographic research as a method for engaging with marginalized urban communities in the context of climate change by documenting resilient vernacular practices and investigating the underlying conceptual frameworks that give them life.

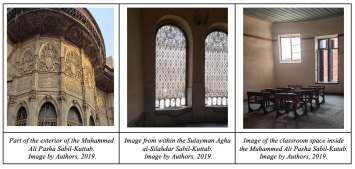

Sabils. The form of the sabil, or charitable water fountain, designed to offer free water to communities and passersby, can be found throughout the islamic world (Mostafa, 1989; Grabar 1984; Sims, 1984; Ebeid, 1976). More broadly, public fountains have historically been a part of many urban traditions (Mostafa, 1989) and Wutich et al. argue that water sharing at a household level is a cross-cultural phenomena in which each location has its own constellation of ethical frameworks, technologies, and ontologies (2017). The form of the sabil under consideration here is marked by its embeddedness in an islamic tradition of the divine providence of water, the impetus to share water, and connections to ideas about accounting for good deeds. In the city of Cairo, there are five main types of sabils.[2] The first are historic buildings where sabils were co-located with kuttab, centers for Islamic education. These sabil-kuttab were primarily established during the Mamluk and Ottoman periods and several have undergone restoration in the 20th and 21st centuries (Mostafa, 1989). Sabil-kuttab were designed to exude the holy properties of water, including its essentialness to life and its role in ritual ablution and cleanliness, and they continue to serve as an embodiment of Islamic teaching (ibid).

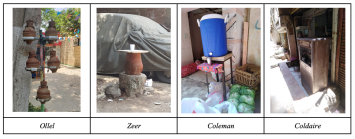

The sabils that are the focus of this research are the four contemporary vernacular forms of charitable water fountains; olla, zeer, coleman, and coldaire. The olla and the zeer are both made out of clay and this composition allows for the cooling of water through the process of drawing heat from the water to fuel evaporation from the exterior surface of the sabil. Ollel (olla singular) are small earthenware containers with wide bottoms and narrow necks. They are often found on a metal olla tree or on a wooden shelf in a collection of three or more. Ollel are the least expensive of the four common sabil types in Cairo, at around 7 to 15 LE, but also the most fragile.[3] Zeers are large clay water containers in a cone shape, often closed with a wooden lid and priced at around 70 LE. The next highest price version of sabil is the coleman, a plastic water container with a spigot, in which ice is the primary cooling agent. Coleman range in price depending on size, from 90 LE to 250 LE. The fourth and final common contemporary iteration of sabil in Cairo is the coldaire, a refrigerated water cooler that requires electrical and water connections. While the coldaire is relatively pricey, at around 1,200 LE for the most common model, it is often the preferred form for both users and keepers of sabils given the expectation that the water is both the coolest and cleanest of the four varieties.

Sabils are important parts of the built environment of Cairo, drawing on religious precedence and enacting everyday ethical notions of reciprocity. Often located in areas underserved by municipal water systems, they are particularly important in the changing environmental conditions of Cairo and point to the ways in which vernacular and small-scale water infrastructure can add to the picture of urban water resilience. Sabils highlight the role of small scale water sharing, an important addition to resource management conversations that focus primarily on large scale issues and state discourses (Leeuwen, Hofman, Driessen, and Frijns, 2019; Pahl-Wostl et al., 2007). In order to explain the reasons for reciprocity in this context, this paper investigates the relationship between “generosity and charity [that is] linked to religion” (Wutich et al., 2018).

Built Environment. The modern city of Cairo has been shaped by its location on the Nile Delta. As one of the largest rivers in the world, the Nile has historically allowed Egypt to flourish by providing fertile soil and a rich water supply. The city’s industries and political centrality have attracted nearly half of Egypt’s urban population to its environs, and between the 1950s and the 1970s Cairo expanded its populations by six times over (Sims, 2012). In the 1960s, residents were living at rates of nearly three persons per room, and today these numbers continue to be exacerbated by restrictive zoning policies and the effects of structural adjustment on a transitioning economy (ibid). Today, nearly two-thirds of Cairo’s population live in informal neighborhoods, with a burgeoning “informal” city built upon a much smaller formal infrastructure.

A series of structural adjustment agreements starting in the 1990s led to a reduction in state spending on collective welfare. The growth of private industries and contraction of public services meant that “people’s everyday necessities [were left] to either the whim of private capital, reach of NGOs, or mercy of charitable institutions” (Bayat, 2012). However, rather than making these places uninhabitable to ordinary individuals, the reduction of public services by the state coupled with neoliberal practices forced the city “inside out” and encouraged individuals to find ingenious ways to operate within these systems (ibid). Cairenes worked to amend and enhance their housing and neighborhoods to suit their needs, creating vernacular built forms (Ghannam, 2002). If individuals could not find opportunities within the urban spaces that they lived in, then they inserted themselves into public spaces and found ways to operate within these new paradigms. Such informal and dense housing practices have created conditions in which much of the social, political and commercial life of the city happens in the street (ibid; see also Ismail, 2006; and Ababsa, Dupret, and Denis, 2012). These hybrid formal-informal systems extend to utility services, with inaccessible or unreliable public provisions for many residents. In informal settlements, such as Ezbet Bekhit, inhabitants rely on a mixture of municipal water provided by the government and water “borrowing” through illegal connections to state water systems (Sims, 2012). As of 2015, officials estimated that 98 % of the Egyptian population had access to at least basic potable water coverage, however there is great variability in coverage between urban and rural spaces, and significant issues with quality (de Albuquerque, 2010). Contestation over water and wastewater systems has been an important factor in the Egyptian political sphere, with challenges over water quality in municipal spaces (Khalil, 2019) and water payment (Farmer, 2017), and both thirst (Piper, 2014) and sewage overflow (Arefin, 2019) played a role in the 2011 revolution.

In this context, the tradition of gifting water through sabils has been extended as a means to reshape the built environment to provide water to people as they live their daily lives; shopping, traversing and doing business on Cairo’s streets in the “city inside-out.” Sabils change the context in which water rights are thought about by altering an individual’s relationship to water. The indirect interaction between sabil-keeper and user allows it to exist as a means of extending water rights to passersby without demanding a justification of need. By being physically present throughout the city, they advocate for more consideration of human needs to be embedded in urban design. As a result, they create a more intimate relationship between water and the user. This is especially important in the context in Cairo in the midst of increasing heat.

While Cairo’s geographic location means it has long been a “hot” city, the heat issues in the city are exacerbated by the “Urban Heat Island Effect” (UHI) and climate change. UHI is a phenomenon that has the potential to raise the ambient air temperature, resulting in increasing thermal discomfort (Abutaleb et al., 2015). The UHI effect on a city’s microclimate is influenced by factors such as size and geometry of urban infrastructure, or so-called urban forms, as well as anthropogenic activity, and the area of impervious surfaces. Larger cities with dense populations, such as Cairo, are more vulnerable to UHI due to the prevalence of tall buildings and narrow streets, which create ‘urban canyons’. These urban canyons effectively trap solar radiation, thus increasing the temperature of the microclimate (Bakarman and Chang, 2015). By using Landsat remote imaging technology, Abutaleb et al. were able to measure the seasonal and diurnal ranges of land surface temperatures for Greater Cairo in 2012, finding that during the summer months, it ranged from 27 °C to 61 °C. The urban areas of Cairo had a recorded land surface temperature 5-22 °C higher on average than in rural areas (Abutaleb et al., 2015). Onto this picture is the rise in temperatures expected for the region as climate change unfurls (Max-Planck-Gesellschaft; Aboulnaga, Alwan, Elsharouny, 2019). While the Egyptian state has attempted to address the growing issue of water scarcity in Cairo by adaptive governance, it falls short due to the prioritization of providing water access to the upper classes for a subsidized fee, while informal residents are often forced to pay more for water from private sources (Eldidi et. al., 2017; Sowers et. al., 2011). The accumulation of sabils in urban Cairo can be viewed as a tangible manifestation of a collective response to this increasing thermal discomfort. With their public use and visibility, sabils not only gift water to passersby, but serve as an example of how climate change corresponds with lived experience as a form of knowledge in local communities (Rignall, 2019).

Water Resilience. As one of the world’s megacities, Cairo faces a number of water challenges which come from a combination of population growth and uneven urban development that intensify in the context of climate change (Enjie, Endter-Wada, Li, 2015). For some, these conditions imply the necessity of doubling down on the push for global standardized water management systems (USAID Water, 2017). However, such a rush to prescribe pre-existing development models to newly climate-intensified water challenges risk the recapitulation of deeply unequal power relationships and the duplication of failed developmental paradigms (Scoville-Simonds, Jamili, Hufty, 2019). Other research proposes alternatives to these water mega-projects through looking to smaller scales for new solutions, such as microgrids (Falco and Webb, 2015) and alternative water sources (ICARDA, 2016). In each context, the search continues for an answer on how to make resilient water systems possible. Resilient water systems are those that can resist change, bounce back in the face of change, or resume a new functional equilibrium in the context of change (Davoudi et al., 2012).

In this article, we examine sabils as a key adaptation of the built environment to gift water in the context of a rapidly heating city. As a critical resource for survival and a human right, reliable delivery of water in an urban area with a centralized structure is necessary. Instead of replacing this structure, sabils act as extensions of Cairo’s centralized water infrastructure. Through the moral practice of localized water sharing and storage for the use of the community, sabils have the potential to increase water infrastructure resilience in situations of insecurity (Rignall, 2019).

Ethical Systems. Water rights are closely tied to a wider set of social relations and water provision systems can be intimately influenced by power relations and social institutions that shape availability and ownership (ElDidi and Corbera, 2017). Water sharing practices are culturally embedded activities that can be both need based and symbolic (Wutich et al., 2018). In Egypt, these social relations stem from moral ideologies concerning religion, property, and reciprocity (ElDidi and Corbera, 2017). In the past, sabils were often supported through a waqf, a legal form that, in part, enables the practice of the Islamic pillar of zakat. Zakat requires believers to provide charitable donations (sadaqat) to the less fortunate. Sabils form mechanisms for gifting water, enabling residents of Cairo to enact these religious precepts and also to offer mutual aid to neighbors in the hot cityscape. Such behaviors are thus part of systems of reciprocity, where sharing is organized by cultural and religious beliefs about how, when, and with whom one shares an expectation of mutual obligation. In such systems, communities recognize the human right to water of their neighbors, even if that human right isn’t being actively recognized by the state (Wutich et al., 2018).

Historically, sabils were placed at junctions along pilgrimage routes in order to provide water for travelers to drink, purify themselves for prayer, or supply themselves for daily activities. The contemporary vernacular sabils, that are the focus of this research, are much smaller in scale but are also often strategically located within their contexts. Sabils are often created by families to honor a deceased relative as a way in which to accrue hasanat, or blessings from God, for the departed. Sabils thus create a socially embedded system of mutual aid, that stems from the teachings of Islam and notions of neighborly relations.

Methods

This research was undertaken as an undergraduate and faculty joint project. Professor Tessa Farmer had previously done research on sabils in another area of Cairo and her work provided a background platform for this project. Importantly, this earlier research established that residents of Cairo were feeling increasingly hot traversing city spaces, and some sabil keepers indicated that this was the impetus to start a sabil (Farmer, forthcoming). Undergraduates Fazlah Rahaman and Mel Throckmorton applied to participate in the research project, with the express purpose of jointly designing and carrying out a project focused both on gaining new insight into water issues and providing undergraduates with a closely mentored research experience. Generous funding from the Center for Global Inquiry and Innovation at the University of Virginia covered the costs of research, thereby removing one of the key barriers to global research for many students. In the eleven months prior to the field work portion of the grant, the group met bi-weekly to assign and discuss existing research pertinent to our project. These regular conversations helped construct the backbone upon which our final research plan was based. Based on her prior research, Farmer facilitated a mentorship with the students by providing background texts and encouraging the students to do their own individual explorations of the topic. The different interests of the three project members allowed for a greater conversation to happen about what questions the joint project should ask about sabils and what methods should be incorporated into the project. Existing anthropological research on the relationship between reciprocity and religious identity, as well as built environment, helped guide the group toward a research focus on the dialectical relationship between ethical systems and the built environment.

The two students were able to continually receive tiered support as the project progressed through the phases of writing a proposal, applying for funding, amending the preexisting Internal Review Board (IRB) protocol, navigating the channels for the university’s International Studies Office’s (ISO) approval, applying for the proper travel documentation, arranging suitable accommodations, discussing cultural differences and safety procedures, collecting research, analyzing the data, and finally writing and revising this article. As Cairo, Egypt, has been classified with a Level 2 Threat Advisory by the U.S. State Department, getting research permission from the university ISO as well as from the Egyptian Ministry of Higher Education proved to be a significant obstacle to the project. Being able to provide documentation of research approval in a city where there is considerable military and police presence was crucial to the success of the project, and the unexpected death of former Egyptian President Mohamed Morsi during our stay heightened already present anxieties. Farmer’s prior research experience made her well-equipped to make sure that she and the student had all required documents and permissions to ensure their safety.

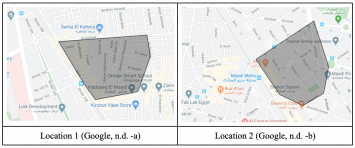

Prior to the departure of Farmer and Throckmorton for Cairo, we identified three potential research locations given Professor Farmer’s previous experience in the city.[4] On the first day of research, we went to the three sites to observe the volume of people and number of sabils to decide which would be best for our research. For the context of the project, it was important that the research sites include a number of visible sabils of the vernacular styles we came to examine. We found that the areas near the metro stations of Hadayek Al Maadi and Al Maadi were well suited to the project. As we were only scheduled to be in Cairo for 17 days, limiting the research to just two sites was also better in case there were complications, considering the trouble that researchers had faced undertaking fieldwork in Egypt over the past several years.[5]

Location 1 near Hadayek Al Maadi metro stop and Location 2 near Al Maadi metro stop are economically distinct, with differing infrastructure and income distributions. Location 1 is an informal, lower-middle class area while Location 2 is a formal, higher-income area, but the fact that both are near metro stations means that both have very high foot traffic. The economic disparity between these two areas is evident when observing the structural differences in built environment. Location 1 was very crowded with few drivable roads and many open storefronts and portable shops which spill onto the pathways; traversable primarily by foot, bicycle, and tuk-tuk. Location 2, in contrast, was dominated by car-accessible roads and the storefronts were not open to the roads, giving it a more closed-off feel. While in Location 1 there were only apartment buildings and stores, Location 2 additionally contained large homes, which were often gated to the streets. To guide this research we look at three main questions: 1) How do residents interact with and how are they influenced by their built environment?; 2) How do ethical systems and built environment interact with and modify each other?; and 3) How does pedagogy impact research? In order to address these questions, we undertook three main research methods.

Transect Walking and Mapping. Transect mapping is useful due to having the dual function of introducing ourselves to the research areas as well as allowing us to gather quantitative data about sabils in a relatively unobtrusive way. By using GoogleMaps to guide us through the streets and walking down each one in a roughly 1.5 km squared section, we were able to create a simple and reliable map of our research area for each site. To denote the sabils we found and briefly describe their type and condition in relation to their surroundings, we used the ‘Pin’ feature on GoogleMaps so that we might be able to go back virtually and see if any patterns arose. This feature also allowed safer navigation of Cairo through the marking of significant landmarks.

Observation. Observation took place adjacent to Locations 1 and 2 but just slightly outside of our 1.5 km squared radius due to concerns for privacy and consent that are outlined by IRB guidelines and ISO regulations. These considerations help protect the people who live in these areas from identification and potential misuse of their personal information. At each research site, we sat near five different sabils for 30-minute intervals for observation, taking notes on what kind of sabils we are seeing (type, quality, quantity), who used them, and how they used them. The location of the sabil and the characteristics of the area surrounding it serve as an important factor in our observations. These observations are crucial in the way that they aid us in later guiding the type of questions we asked in our interviews. It is important to note, however, that as two white, western, and feminine-presenting people, we can assume (and did, in fact, observe) that individuals’ behaviors change around us, and perhaps these changes carry over to how and if they chose to use sabils.

Interviews. Similar to considerations for participant observation, it was important to only do interviews at sabils that were not in our research areas. We sampled both sabil-users and sabil-keepers to see the motivations for both using and maintaining a sabil, and their relationships to them. We were careful to get consent for the interviews usingIRB standards for informed consent in research and ensured that additional consent was received prior to recording our conversations. Interviews were conducted in Arabic with the help of a translator for Mel, who is not proficient in the language. Interviews ranged from 5-15 minutes and though there was a set of guiding questions, each interview differed in context and direction based on the personal experiences of the individuals with whom we were speaking.

This combined set of methods was used in the order listed, giving us the ability to navigate the space in a way allowing us to make overall observations about the built environment for the research area, and then return to focus in on the sabils as individual pieces of the space. Without the context of the surrounding built environment, any framing observations or questions on sabils would lack the connections that we sought to associate with sabils being an extension of that space. Interviews allowed us to connect the information gathered from the unobtrusive methods of transect mapping and observations to individual lived experience and memory. Through these conversations, we are able to begin to see the manner in which an individual’s attachment to memory and experiential knowledge influences the way in which they interact with their surroundings.

Results & Discussion

Studying sabils enables an examination of vernacular changes to built environment, insight into the ethical systems that undergird these modifications, and details on how residents of Cairo use these cultural forms of gifted water. In total, our research documented 43 sabils over the two research locations. The coldaire was the most common form of sabil that we encountered, with twenty in Location 1 and four in Location 2. In our two research quadrants, we found eleven coleman in Location 1 and four in Location 2. We found two groups of ollel in Location 1 and one group in Location 2 placed on the street as sabils. We found only one zeer, in Location 2.[6]

We interviewed three sabil keepers and two users who were adjacent to each research area, for a total of six and four respectively.[7] All six of the sabil keepers had sabils at or adjacent to their shops. Adjacent to Location 1, they were located near a plumbing store, a falafel stand, and a tailor’s shop. Adjacent to Location 2, the sabils were located near to a small food goods store, a small restaurant for grilled meat, and outside a tourist nic nac shop located near a stairway overpass over the metro line.

Based on our transect walking, we observed that sabils were especially common near shops, restaurants and metro transportation hubs. In Cairo, the three metro lines help serve over four million passengers every day.[8] Subsequently, these sites are a prime zone for sabils because they maximize the number of pedestrians and increase the amount of hasanat generated. Our research elucidated the relationship between sabils and economic status of an area, with many more sabils in Location 1 (33 total) than in Location 2 (10 total). We hypothesize that the reasons for this difference lay in the economic status of the neighborhoods, which influence both the water options available to people in these spaces and the physical design of the areas themselves. Firstly, Location 1 contains primarily working or lower middle-class residents who have fewer financial resources than those in Location 2, and therefore less ability to pay for bottled water when in the street. Location 2 has a greater presence of middle and upper middle-class residents of Cairo, and therefore more often have the resources available to pay for bottled water and are more likely to move through the streets in automobiles. There were working class and middle-class pedestrians and workers present in Location 2, and we hypothesize that those sabils present in Location 2 were geared towards those workers and lower income pedestrians. However, only additional research could verify this claim. Secondly, Location 1 more closely hews to the logic of the city-inside-out, where most of the streets are accessible primarily to pedestrians and small vehicles (tuk tuks, motor bikes, and bicycles), and stores are open to the street. Cairenes inhabiting Location 1 are therefore likely to be walking longer distances in the hot cityscape than those in Location 2.

Ethical The research examined community reciprocity and Islamic religious traditions about the importance of sharing water as interrelated ethical frameworks that influenced our interlocutors’ choices to create vernacular sabils. In each of the ten interviews with sabil keepers and users, interlocutors indicated that religious precepts were key to the form and function of sabils. Users shared verses from the Quran about the importance of water, such as “Have those who disbelieved not considered that the heavens and the earth were a joined entity, and We separated them and made from water every living thing? Then will they not believe?” (Quran 21: 30) and hadith such as one about a man who went to heaven specifically for giving a dog water in his shoe.[9] There was a variety of self-expressed levels of religious knowledge among the sabil keepers with whom we spoke, from those who were able to offer detailed explanations of hasanat, to those who seemed to be pulling from collective local knowledge and motivated to a greater extent by attachment to a departed loved one. There was general acknowledgment, however, that perfect knowledge was not required for the process to work, as demonstrated in the following interview:

Interviewer- How do the hasanat work?

Sabil Keeper- This is from god. We [simply] do, and god rewards us as he sees fit. But we don’t know how the rewards come.

Interviewer-Why did you choose this method of doing a good deed, among the different possible ways?

Sabil Keeper- Yes, there are other things but this one… Look, if someone is thirsty and you gave them a drink, you get a reward for that. And this is a [busy] road and everybody who comes by who drink from it, and you get rewards for that.

Interviewer-This [sabil] is [intended as] sadaqah jariyah, right?[10]

Sabil Keeper-Yes, this is sadaqah jariyah. You could put money into a mosque that is being built. Also, there are shrouds for a dead person.

Interviewer-But this is the best thing to invest in [for hasanat]?

Sabil Keeper-It’s a good thing, Ok? There are other things, but I think that this is the best one because someone who is thirsty has their thirst quenched. We say that, but we aren’t certain because God is the one who gives rewards for it.

As with other interviewees, this individual indicated motivations that are rooted in religious ideas and in a sense of connection to place.[11] Four of the six sabil keepers specified that the sabil was dedicated to the soul(s) of departed loved one(s), while the one keeper in Location 1 maintained the sabil on behalf of a mosque and one keeper in Location 2 said that he had set up the sabil in order to help those who he saw were thirsty in the street.

As this last keeper in Location 2 highlights, a sense of shared social bonds and a common experience of moving through the hot cityscape of Cairo is another tie in the logic of sabil practices. Sabil keepers mentioned vulnerable populations as key to their desire to gift water, often citing children, the elderly, and those who had diabetes or needed to take a pill as intended recipients. Additionally, nonhuman residents of the city were also included in the set up of several of the sabils that we encountered, with bowls for animals underneath the main sabil structure. Sabil keepers were canny in their reciprocity, choosing locations near to where they work or next to their homes where they could easily maintain the sabil and maximize foot traffic. Keepers also were well aware of the neighboring sabils, and several offered us verbal maps of gifted water available in nearby streets. In one instance, a coldaire was located beside an outdoor refrigerator that is customarily used to gift uneaten food to those in need, connecting it to a greater existing framework of charitable giving (Mittermaier, 2019).

Use

“It will make your heart happy to talk about charity” (from Interview 3, Location 1)[12]

During participant observation at sabils, there were a variety of both sabil users and maintainers. Passerby showed preference for certain sabil types and characteristics, while the sabil keepers that were interviewed had different reasons for how and why they maintained one. This preference is partly shaped by the distinctions between the four vernacular types, but there was no uniform answer to what is the “best” sabil. Each form of sabil is able to meet water demands by being both accessible and in working order, with each form differing in how that access is provided to the user as well as its ability to be maintained by the keeper.

Considering sabil preference, it is important to mention that not everyone we talked to thought of sabils in the same manner. Although a large amount of people utilize them, not everyone attaches the same qualities and religious significance to their choice to use and maintain them. During interviews, we asked each person if there was a sabil that they preferred, and received a range of answers from a simple response to ‘ranked’ lists of which were better and why. The coldaire and coleman are preferred by some users due to the temperature of the water and expectations of cleanliness, with the coldaire being an enclosed, self-refrigerating unit and the coleman having a top that keeps out foreign materials and makes it easy to add ice throughout the day. In contrast, the ollel is a more open structure with small pores cut into the stem so that the water can naturally filter itself throughout the day. We only saw one zeer while mapping both research locations, and when we asked individuals why, they said that the zeer is too large to be conveniently portable like the ollel, as well as were generally regarded as unclean due to the open top. In addition to the openness of the sabil type, the hygiene of mouth-to-sabil contact seems to play a role in preference, with some users choosing to bring their own vessel for drinking or cupping their hands instead of using the cups that were placed there for communal use. Although the coldaire is very popular for its coldness, some people tend to avoid it due to its self-refilling properties implying that it does not get cleaned or maintained as often as coleman or ollel. Nevertheless, one particularly expensive-looking coldaireoutside of a mosque in Location 1 was used so frequently that the motor didn’t even have time to cool the water before it was drawn down by users. One woman we interviewed prefers the ollel for drinking because she says that because clay is from nature, drinking it makes one closer to God. This is just one instance of the idea that the form of the sabil transforms the quality of the water. We indirectly found through questioning that the belief that water from sabils is ‘sacred’ is commonly held, and can be observed in the way that people use them.

While sabils may be accessible to anyone, there are still known rules to be followed for their use. The sabil as an object and the water within it both fall inside of a religious domain of respect, and to disrespect either is to incur evil instead of the hasanat that one would normally receive from using one. We noticed that after drinking, some individuals would replace the cup on top of the coleman or coldaire without pouring out the excess water, leaving it for the next person instead. At one coleman in Location 2, we witnessed three young men drink and subsequently use the excess water to wash their hands and faces. Some sabil keepers had placed buckets or bowls under their sabil (particularly colemans) to catch any water that might drip from the faucet for the benefit of street cats and dogs.

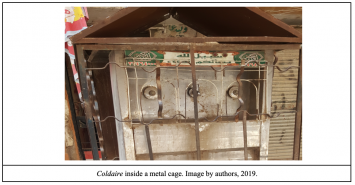

Despite the embedded system of respect present, misuse of sabils is still apparently common enough to warrant keepers exercising caution. While the coldaire is a permanent fixture with piped water and connections for drainage and electricity, the portable nature of coleman allows them to be taken inside at night to be cleaned and to prevent them from being vandalized or stolen. A shopkeeper who kept a sabil in memory of his late father stated that he selected his sabils, a coleman and a set of ollel, out of concern for this. In an interaction with a woman in the observation phase of research who had an empty ollel tree outside of her home next to a functioning coldaire, she stated that she decided to buy the more durable coldaire after having several of her ollel broken. A majority of surveyed coldaire had cage-like structures protecting them on the outside with an opening for the faucets that sometimes mimicked the fonts on the architectural sabils (See image below) that helped decrease the likelihood of them being damaged by vehicles and prevents theft or tampering with the water. In this way, the behavior of sabil users is actually able to shape their form and how they are maintained.

Sabil keepers select the form of their sabil based both on the preferences of the user, and the ease by which they can be maintained. At a few sites we observed, more than one form of sabil would be present in one space and maintained by the same person or family, thus giving sabil users a choice. Sabils in each research site appeared to come with varying levels of cleanliness, appearance and working condition. In Location 1, although we noted that the majority of sabils there were coldaire, a large number of them were broken and not being maintained. Fardouze mosque, a famous location for studying Quranic recitation, had four coldaire outside of it signifying its relevance to passersby, yet only two of them were actually working during our first visit to Location 1. On our second visit to the area of the mosque, we met a repairman who ran a workshop specializing in coldaire. He stated that the Imam of the mosque had called him to look at the coldaire, which opened the question for us of the role of religious institutions in maintaining sabils. Many sabils, usually a coldaire, were located outside of mosques in both research locations. From interviews we learned that mosque congregants would sometimes endow a sabil as a collective, thus gaining all who contributed to its purchase and care hasanat. One mosque coldaire even had a metal collection box attached to it for donations. The mosque as a highly trafficked space is more likely to gather sabil users, and individual keepers also appear to consider the greater outdoor space when placing their sabils.

During our trip in June, the placement and filling of most coleman and ollel started around noon, when the shops began to open on the streets and which also happens to coincide with the hottest time of the day. These portable sabils would sometimes be strategically placed in the shade to keep them cool throughout the day, serving the dual purpose of both mitigating thermal discomfort of users and decreasing the amount of times that the keeper has to replace the ice or refill with water during the day. In Location 2, a souvenir shop owner placed his coleman in the middle of a nicely maintained square in front a stairway over the metro line. Everyday, he would bring his ice for the sabil from home despite the inconvenience because he believed that the water there was nicer than what was present on site, refilling it as often as three times per day. Sabils keepers sometimes placed signs on the sabil asking for specific prayers for the souls of the departed loved ones to whom the sabil was dedicated. Some sabils showed evidence of an effort to maintain a nice outward appearance. In Location 1, a woman put what appeared to be a significant amount of care into her coldaire’s appearance by neatly placing decorative plants next to it. She came outside after watching us from her balcony to ask us what we were doing, and upon learning that we were interested in sabils, ran upstairs and promptly returned with two brand new glasses for us to drink with in memory of her son.

The above examples help demonstrate how the relationship between sabil-user and keeper extends even further to include how these individuals interact with the built environment as a whole. Both using and maintaining a sabil is a conscious choice, and attracts a variety of users within the spaces they occupy that are not explicitly tied to the keeper of the sabil itself or the sense of attachment it may represent. A prominent example of this from our research was one sabil-user we interviewed briefly outside of a mosque who was a Christian. He stated that he used sabils as source of water frequently, and despite his religious beliefs always tried to remember to say a prayer on behalf of the sabil-keeper out of appreciation for the gifted water.

Conclusion

As water insecurity becomes a greater global issue, it is important to stress the role of local communities in managing their own resources. Large-scale developmental projects have historically often served as a means for “green-grabbing” or controlling these resources in a way that is extractive and not beneficial to the communities directly impacted (Rignall, 2019). The implications of a community-built system based on religious and moral values that promotes water resilience are compelling for further research into sustainable infrastructure and its relationship to culture. This preliminary research into sabils points to the dialectic relationship between ethical systems and the ways in which the built environment is modified to meet people’s changing water needs in the city-inside-out. The geographic and political situation in Egypt, coupled with the inability of the government to keep up with the needs of a still-growing population, increases the risks associated with climate change, particularly for the residents of settlements that are regarded as illegitimate or ‘unplanned’ by the state. In these contexts, climate change can behave as a “threat multiplier” that exacerbates already poor conditions faced by marginalized groups (Sowers et. al., 2011). These micro-scale adaptations serve not just as a source of local knowledge on water resilience, but add to a greater insight on what circumstances create the need for such adaptations.

Pedagogically, this project adds to sustainability education in two ways: through ethnographic engagement with the embodied experience of climate change to highlight local systems of adaptation and cultural elaboration; and by emphasizing the mentor-mentee role in knowledge production. Ethnographic methods enabled us to take a close up view of small scale and unofficial adaptations to the built environment, to have an embodied experience of the urban landscape, and to engage with marginalized urban residents to better understand the ethical and practical systems that undergird them. As a research group, the collaborative process enriched the research aims and conversations and brought a diverse set of skills to the table: anthropology, computer science, hydrology, and development studies. Professor Farmer’s knowledge of the city, gained through years of research (in the beginning of which she herself was guided by mentors), allowed the team to safely navigate an increasingly challenging research context and obtain necessary university approval. This project was enriched by the intimate student-faculty relationships. Throughout this process, Professor Farmer was deeply invested in both the research topic at hand and also the future implications this project would have for her students (i.e. the tangible skills students would be able to learn and take away for their own endeavours). Student investment grew by being in conversation about defining what the research would look like. In considering the career and academic opportunities of their students, professors can tailor research endeavours to the academic and career goals of their students so as to involve students in the process. This theoretically makes their work lighter while providing student fellows the opportunity for research.

In terms of logistics and applying our research, this opportunity allowed students a graduated opportunity to be guided through the process of research and the art of writing. Weekly conversations and directives provided undergraduate researchers targeted objectives and methods of tackling the process of applying for IRB approval, narrowing down a research questions, and identifying useful resources to read. This allowed students to develop the metacognitive skills involved in writing a research article without being overwhelmed by their first experience. In addition, these meetings provided an opportunity for equal exchange where undergraduate researchers could voice their concerns, ask for assistance and also set expectations of what is required from the students. This was Throckmorton’s first time abroad, and as a scholar interested in development, the value of having an experienced mentor to help them navigate these spaces with regards to positionality can not be overstated. When studying these environmental landscapes from the comfort of a western space, it is difficult to understand fully the bodily experience of walking through urban Cairo in the intense summer heat or the difficulty of accessing water that is inexpensive and clean. It is difficult for this degree of experiential knowledge production and cooperation between a professor and their students to occur within the confines of the classroom, and this is a pedagogical relationship that continues to be cultivated by extending the dialogue beyond this particular research project.

References

Ababsa, Myriam, Baudouin Dupret, and Eric Dennis. Popular Housing and Urban Land Tenure in the Middle East : Case Studies from Egypt, Syria, Jordan, Lebanon, and Turkey. AUC, 2012.

Aboulnaga, Mohsen, Amr Alwan, and Mohamed R. Elsharouny. “Climate Change Adaptation: Assessment and Simulation for Hot-Arid Urban Settlements – The Case Study of the Asmarat Housing Project in Cairo, Egypt.” In Sustainable Building for a Cleaner Environment: Selected Papers from the World Renewable Energy Network’s Med Green Forum 2017, edited by Ali Sayigh, 437–49. Innovative Renewable Energy. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2019.https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-94595-8_37.

Abutaleb, Khaled, Adeline Ngie, Ahmed Darwish, Mahmoud Ahmed, Sayed Arafat, and Fathi Ahmed. “Assessment of Urban Heat Island Using Remotely Sensed Imagery over Greater Cairo, Egypt.” Advances in Remote Sensing 04, no. 01 (2015): 35–47. https://doi.org/10.4236/ars.2015.41004.

Arefin, Mohammed Rafi. Infrastructural Discontent in the Sanitary City: Waste, Revolt, and Repression in Cairo.” Antipode 51: 4 (2019): 1057–78.

Bakarman, Mohammed, and Jae Chang. “The Influence of Height/Width Ratio on Urban Heat Island in Hot-Arid Climates.” Procedia Engineering 118 (December 31, 2015): 101–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2015.08.408.

Bayat, Asef. Life as Politics: How Ordinary People Change the Middle East, Second Edition. Stanford University Press, 2013.

Davoudi, Simin. “Resilience: A Bridging Concept or a Dead End? Planning Theory & Practice 13, no. 2 (June 2012): 299–333. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2012.677124.

de Albuquerque, Catarina. Report of the independent expert on the issue of human rights obligations related to access to safe drinking water and sanitation (Geneva: United Nations Human Rights Council, 2010). https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/686900.

“Egypt’s Largest Metro Station in the Middle East to Be Inaugurated on Sunday | Egyptian Streets.” Accessed October 30, 2019. https://egyptianstreets.com/2019/10/19/egypts-largest-metro-station-in-the-middle-east-to-be-inaugurated-on-sunday/.

ElDidi, Hagar, and Esteve Corbera. “A Moral Economy of Water: Charity Wells in Egypt’s Nile Delta: A Moral Economy of Water.” Development and Change 48, no. 1 (January 2017): 121–45. https://doi.org/10.1111/dech.12286.

Falco, Gregory J., and Wm. Randolf Webb. “Water Microgrids: The Future of Water Infrastructure Resilience.” Procedia Engineering 118 (2015): 50–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2015.08.403.

Farmer, Tessa. “Willing to Pay: Competing paradigms about resistance to paying for water services in Cairo, Egypt” Middle East Law and Governance Journal 9 (2017): 3-19.

Google. (n.d. -a) [Google Maps, Location 1]. Retrieved February 21, 2020, from https://www.google.com/maps/d/viewer?mid=15tQIN4ekLZGE_37WKrecL30KrfjxmYtP&usp=sharing.

Google. (n.d. -b) [Google Maps, Location 2]. Retrieved February 21, 2020, from https://www.google.com/maps/d/viewer?mid=1bBC_ZsiMnmFrbT-oEIPfZRZy4BRhf-UB&usp=sharing.

Ghannam, Farha. Remaking the Modern Space, Relocation, and the Politics of Identity in a Global Cairo. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002.

Grabar, Oleg. “Places, Citadels and Fortifications,” in Architecture of the Islamic World: Its History and Social Meaning, ed. George Mitchell (London, 1984).

ICARDA. “New Hope in Egypt for a Resilient Urban Water Infrastructure System.” Accessed October 29, 2019. https://www.icarda.org/media/news/new-hope-egypt-resilient-urban-water-infrastructure-system.

Ismail, Hossam. “Historical Introduction to Islamic Architecture in Old Cairo.” Museum International 57, no. 1–2 (May 2005): 111–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0033.2005.00519.x.

Khalil, Deena. “The Flexible Governance of Water in Cairo’s Informal Areas.” Water 11, no. 8 (August 2019): 1644.https://doi.org/10.3390/w11081644.

Leeuwen, Kees van, Jan Hofman, Peter P. J. Driessen, and Jos Frijns. “The Challenges of Water Management and Governance in Cities.” Water 11, no. 6 (June 2019): 1180. https://doi.org/10.3390/w11061180.

Li, Enjie, Joanna Endter-Wada, and Shujuan Li. “Characterizing and Contextualizing the Water Challenges of Megacities.” JAWRA Journal of the American Water Resources Association 51, no. 3 (June 2015): 589–613. https://doi.org/10.1111/1752-1688.12310.

Middle East Studies Association. “Middle East Studies Association.” Accessed October 30, 2019.https://mesana.org/advocacy/letters-from-the-board/2019/02/04/revised-security-alert-on-egypt-february-2019.

Mittermaier, Amira. Giving to God Islamic Charity in Revolutionary Times. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2019.

“More Climate Refugees from Middle East and North Africa | Max-Planck-Gesellschaft.” Accessed October 31, 2019.https://www.mpg.de/10481936/climate-change-middle-east-north-africa.

Mostafa, Saleh Lamei. “The Cairene Sabil: Form and Meaning.” Muqarnas 6 (1989): 33. https://doi.org/10.2307/1602278.

Pahl-Wostl, Claudia, Marc Craps, Art Dewulf, Erik Mostert, David Tabara, and Tharsi Taillieu. “Social Learning and Water Resources Management.” Ecology and Society 12, no. 2 (2007). https://www.jstor.org/stable/26267868.

Karen Piper. The Price of Thirst: Global Water Inequality and the Coming Chaos. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2014.

Rignall, Karen. “Living Climate Change in the Middle East and North Africa.” International Journal of Middle East Studies, undefined/ed, 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020743819000710.

Scoville-Simonds, Morgan, Hameed Jamali, and Marc Hufty. “The Hazards of Mainstreaming: Climate Change Adaptation Politics in Three Dimensions.” World Development 125 (January 1, 2020): 104683. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.104683.

Sims, David. Understanding Cairo: The Logic of a City Out of Control. Reprint edition. Cairo ; New York: The American University in Cairo Press, 2012.

Sims, Eleanor, “Markets and Caravanserais,” in Architecture of the Islamic World: Its History and Social Meaning, ed. George Mitchell (London, 1984).

Sowers, Jeannie, Avner Vengosh, and Erika Weinthal. “Climate change, water resources, and the politics of adaptation in the Middle East and North Africa.” Climatic Change 104, no. 3-4 (2011): 599-627.

“Water and Sanitation | Egypt | U.S. Agency for International Development,” April 19, 2018. https://www.usaid.gov/egypt/water-and-sanitation.

Wutich, A., J. Budds, W. Jepson, L. Harris, C. Staddon, A. Wutich, J. Budds, W. Jepson, L. Harris, and C. Staddon. “Household Water Sharing: A Review of Water Gifts, Exchanges, and Transfers across Cultures.” Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews – Water, June 2018. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/journal/20491948.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Hemeda Ibrahim Moussa Hemeda for his diligent work as an interpreter and guide in Cairo. Cliff Maxwell and Brian Owensby at the Center for Global Innovation and Inquiry at the University of Virginia were generous supporters of this research through the Faculty Global Research with Undergraduates award. Additionally, we would like to thank Director of Global Studies Richard Handler and MESALC Chair Nizar Hermes for their many-layered support. Mona El Khafif from the UVA School of Architecture was generous with her time and expertise as we planned our methodology. Carol Westin and Aida Barnes were instrumental in making the logistics of this research work. We would also like to thank Catarinia Krizancic and Sheena Singh in the Office of International Studies for their assistance navigating the security questions in the University and beyond.

[1] Sabil (singular: sabīl; plural: subul) is an arabic term meaning path or means, and colloquially understood as referring to charatiable water fountains. We have chosen here to use the English plural form for ease of reading.

[2] In rural spaces there are additional varieties of sabil, including a hand-pump called a trumba, which call for additional research (ElDidid and Corbera, 2017).

[3] During our research period of June 2019, the average exchange rate for 1 USD was 16.672 Egyptian Pounds.

[4] Due to a late-breaking time conflict, Fazlah Rahaman was unfortunately unable to travel to Cairo. He remained an active participant in the data analysis and write up portion of the project in addition to his early work on grant writing and pre-departure organizing.

[5] These difficulties are laid out by the Middle East Studies Association’s Security Alert for Study and Research in Egypt. https://mesana.org/advocacy/letters-from-the-board/2019/02/04/revised-security-alert-on-egypt-february-2019. Accessed October 29, 2019.

[6] Future research will return to these two locations to assess any changes in the prevalence of sabils in these areas.

[7] Unfortunately, our research period was cut short due to mounting tensions and increased police presence along the metro system due to the death of Mohamed Morssi, the previous president of Egypt who was ousted after one year, while in court on espionage charges. Therefore we ended up collecting fewer interviews than we wished.

[8]https://egyptianstreets.com/2019/10/19/egypts-largest-metro-station-in-the-middle-east-to-be-inaugurated-on-sunday/. Accessed on October 27, 2019

[9] Sahih al-Bukhari 5663, Sahih Muslim 2244

[10] Sadaqah Jariyah, or ceaseless charity, is one of three ways in which souls can accrue hasanat after death according to hadith.

[11] All of the sabil keepers we interviewed were men, although this gender disparity was not the case in Professor Farmer’s previous research on sabils in a different area in Cairo. That this was the case could have been due to chance given the small sample size of those interviewed, and could also have been in part due to the mixed gendered group research format where it would more socially appropriate to direct our mixed-gender group to speak to a man in situations in which sabils are cared for by family groups.

[12] Tessa Farmer’s previous research on potable water and wastewater in Cairo lead to the focus on sabils, as it was a key form of gifting water in the city and a topic about which people enjoyed speaking.

Tessa Farmer is an Assistant Professor at the University of Virginia, where she serves as Track Director for the Global Studies Middle East and South Asia major. She received her training in Anthropology at the University of Texas at Austin, and her current research focuses on everyday water and wastewater practices in Cairo, Egypt. She can be reached at trf6k@virginia.edu

Tessa Farmer is an Assistant Professor at the University of Virginia, where she serves as Track Director for the Global Studies Middle East and South Asia major. She received her training in Anthropology at the University of Texas at Austin, and her current research focuses on everyday water and wastewater practices in Cairo, Egypt. She can be reached at trf6k@virginia.edu  Mel Throckmorton is an undergraduate at the University of Virginia (2020) pursuing a BA in Environmental Science and a BA in Global Studies with a concentration in the Middle East and South Asia. They have an interest in attending graduate school to study Civil Engineering in the future. They can be reached at mpt2dj@virginia.edu

Mel Throckmorton is an undergraduate at the University of Virginia (2020) pursuing a BA in Environmental Science and a BA in Global Studies with a concentration in the Middle East and South Asia. They have an interest in attending graduate school to study Civil Engineering in the future. They can be reached at mpt2dj@virginia.edu  Fazlah Rahaman is a recent graduate from the University of Virginia (2019) with a degree in Global Studies with a concentration in the Middle East and South Asia. They are currently completing a two-year commitment with Teach for America and plan to attend graduate school in the future. They can be reached at fr4wa@virginia.edu

Fazlah Rahaman is a recent graduate from the University of Virginia (2019) with a degree in Global Studies with a concentration in the Middle East and South Asia. They are currently completing a two-year commitment with Teach for America and plan to attend graduate school in the future. They can be reached at fr4wa@virginia.edu