The Body that is a River

Delehanty Pearkes JSE March 2020 Water Issue PDF

Link to JSE March 2020 Water and Climate Issue Table of Contents

Everything I ever needed to know about sustainability I learned from attending a salmon re-joining ceremony, beside a Columbia River reservoir on August 19, 2019. I learned about logos—the relentless logic of hydro-electric development, and about soma—the often undiscussed body that is a river. I watched in surprise as logos and soma intersected at eros – love. In the coming era of climatic uncertainty, we each and all have the opportunity to converge these forces ourselves, to restore something that has been nearly lost.

Figure 1. A woman from the Wenatchee tribe listens to leaders before the ceremony begins. From: author.

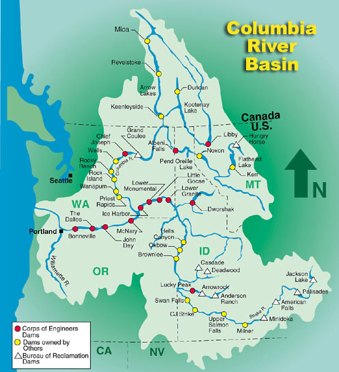

The Columbia River basin is the fourth largest watershed by volume in North America. Descending from the Continental Divide to the sea in just 1,200 miles, the river traverses diverse landscapes in a watershed the size of France, comprising portions of seven western United States and the province of British Columbia, Canada. The snow-charged system hosts over 400 dams, with 15 mega-projects on the main stem. The Columbia River Treaty (1964) between the two countries serves to maximize hydro-electric productivity in both countries, and provide reliable flood control for Portland, Oregon (a city developed extensively on natural floodplain). When Canada and the U.S. designed and ratified the agreement, water supply seemed endless. As the two countries engage in a complex re-negotiation of the treaty, they do so in a greatly changed world where water’s gifts can no longer be assumed.

Figure 2. The international Columbia River Basin extends into both Canada and the United States. From: Environmental Protection Agency. Retrieved from: https://www.epa.gov/columbiariver/about-epas-work-columbia-river-basin.

For a few decades now, scientists and governments have been measuring the effects of drought in the mid-Columbia basin. They forecast the decline (and in several cases entire disappearance) of high mountain glaciers that have long been part of the region’s constant water supply. With spring and summer outflows from the river constrained by irrigation and hydropower production, water has become something to grasp for, rather than assume. Ocean salmon, long imperiled on the Columbia and its tributary Snake River systems, experience year after year of struggle to survive while other interests see salmon flows as contrary to their own needs. Some scientists are ringing the death knell for the iconic fish that once numbered 16 million annually, swimming up to the Rocky Mountains to spawn for more than many millions of years. For nearly a century, Columbia River Indigenous tribes have watched ever-dwindling stocks of Chinook travel upstream through many fish ladders on the lower and mid-river, only to be stopped by Chief Joseph Dam (236 feet high) and Grand Coulee Dam (550 feet high), behemoths that provide no passage. Columbia River salmon survive in the thousands instead of millions. With climatic changes further constraining water supply, the coming era seemed an unlikely one to invest much hope in the salmon

Figure 3. The Columbia River Basin, with dots representing some of its many dams. From: From: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Retrieved from: https://www.nwd.usace.army.mil/Media/Fact-Sheets/Fact-Sheet-Article-View/Article/475820/columbia-river-basin-dams/.

And yet, the tribes do. It is, they say, their responsibility to do so.

In 2012 an historic rainy June brought Columbia River reservoirs to maximum flood control capacity. Water passed through Chief Joseph Dam at such a rate that it overflowed downstream onto a flight of concrete maintenance stairs. The tribe that manages the fish hatchery found salmon ascending these stairs, seeking passage over the dam. Observing the persistence of this fish has always inspired tribal advocacy for the fish, who say that they need two things in a new treaty: access around Chief Joseph and Grand Coulee, to reach historic spawning habitat in Canada that is cooler and more hospitable; and water that moves.

Now that re-negotiations have begun, operators of the hydro-power utilities, U.S Army Corps of Engineers, and both national governments have tried in various ways to change the conversation from salmon. Anything, it seems, other than to allow water to move, falling “wasted” to the sea. The Army Corps of Engineers (operator of both Grand Coulee and Chief Joseph dams) has no plans to erect any passage (too expensive) or advocate for a relaxation of flood control operations (too dangerous). However, what the Columbia River tribes are asking for is not radical. They advocate only for the maximum spring flow already permitted under the current treaty. They urge this more liberal flow only in hot, dry years, to help the salmon.

After nearly two decades of tireless advocacy, scientific research and meetings with agencies, the tribes recently decided to assert their cultural values through action: a cultural release of fish above Chief Joseph and Grand Coulee dams. They called this release of 60 fish a spiritual “re-joining.” The Chinook who returned to spawn on the upper Columbia River in 1942 when Grand Coulee was completed had never been able to make it home. The cycle had been broken. It was time to close the loop. One hot, breezy summer morning, they gathered at the shores of Grand Coulee Dam’s 125 mile-long-reservoir to release Chinook into water that had not felt the belly of salmon in nearly 80 years.

Figure 4 (left). Tribal members waiting for the salmon to arrive. From: author. Figure 5 (right). D.R. Michel (left), Executive Director of the Upper Columbia United Tribes, and Rodney Cawston (holding microphone) Council Chair of the Colville Confederated Tribes, standing with other tribal leaders at the water’s edge. From: author.

***

When I arrived at an unmarked asphalt boat access ramp on Grand Coulee’s reservoir near Keller, Washington, many tribal members had already assembled beside the vast body of controlled water. Some women wore the colorful, traditional dresses, scarves and beaded bags of ceremony and celebration. Drummers assembled around “the big drum,” under a cloth canopy. Elders sat nearby in rows of chairs. With the water lapping at his heels, Colville Confederated Tribes Chairman Rodney Cawston spoke of the hard work that had preceded the day, pointing in particular to D.R. Michel, the executive director of the Upper Columbia United Tribes, an agency based in Spokane, Washington. For two decades now, Michel has quietly and persistently worked with state and federal governments in the U.S.; he has met with hydropower producers and scientists; he has encouraged non-governmental organizations to advocate for the rights of salmon within the tightly managed Columbia River system.

As a recurring, ever-renewing food source, salmon demonstrate the universal potential for natural systems to be both abundant and sustainable. As a spiritual being, salmon evoke a heart’s resilience, persistence and grace, its survival through strife. Born in fresh water, the fish transforms its entire endocrine system to be able to inhabit the sea. Near life’s end, it reverts back to freshwater habitat, pushing upriver to its natal stream, where it spawns for the future, then dies. The capacity to swim these long distances (as far as 2,000 kilometers upstream from the Pacific Ocean to headwater spawning grounds) demonstrates awesome physical strength and a focused desire that through no great stretch can be called eros. The lifecycle of this keystone species is at once mysterious and inspiring, a template for the bonds that form not through the mind of science but through love.

While the tribes have tracked the behavior and character of salmon for thousands of years, the Western mind has only relatively recently developed ways to follow the fish. Contemporary Columbia River salmon have recently been equipped with radio transmitters for technical research. The size of an AA battery, these telemetry tags sit in the stomachs of the fish. The antennae wire comes out of the mouth and drags behind the salmon as it swims. Because the procedure is invasive, the tribes advocate for only minimal use of a technology has helped to create maps proving the remarkable journey Columbia River salmon make – often ranging as far as the coast of Siberia in their fluid migration back and forth across the Pacific.

When the salmon return, they sometimes turn up the wrong major tributary in search of the place where they were born. For reasons that biologists still don’t understand, Columbia River salmon can swim up the Fraser or the Klamath, then turn back out and keep searching. Some call this uncanny ability of the salmon to home themselves a sensory knowledge akin to smell, imprinted on the otolith, or the ‘ear stones’ of the fish, located behind the brain. I think of the homing instead as an extrasensory perception, one far beyond the capacity of our own human minds to understand.

It is possible that only our hearts can fully perceive the journey these fish undertake within their gorgeous, pulsing bodies.

Beside the Chief Joseph Dam reservoir, sunlight glitters happily off the water, as if it knows that today, for just a few minutes, it will be a river for salmon. More tribal people arrive. I am one of few with pale skin hidden from the fierce summer sun under a broad-brimmed hat. Mostly, those gathered here are from various tribes in the region: the Sanpoil, Nez Perce, Lakes, Skoyelpi, Okanagan, and others. A long line forms, stretching from the shore far up the access road. Everyone is waiting. Waiting for the fish to arrive.

Figure 6. Gathering next to the Chief Joseph Dam reservoir. From: author.

In the days before settler contact, it was the same. Waiting. Waiting patiently, with no assumption that the salmon would actually return. The homing was always a miracle, a divine and mysterious gift. A runner from villages along the Columbia would carry the exciting news upstream to the next village, arriving well ahead of the fish. The news signaled the Salmon Chief’s riverside prayers to focus in earnest. As the fish pushed their way against the spring snowmelt current, seeking and knowing beyond words, the reunion was anticipated on land with the force that propels two lovers into each other’s arms. Over millennia, the salmon have worn a groove in the hearts of the people.

After what seems like many hours (but in the end is only one), the piercing backup-beep of a truck causes excitement to ripple through those assembled. The state-of-the-art fish transport truck owned by the Colville Confederated Tribes had been scheduled to arrive late, so that everyone had already gathered and was ready. At the top of the access road to the launch, the truck inches down the long road. Drumming and singing begin. The people form two parallel lines, each leading down to the water.

Figure 7 (left). Removing salmon from the refrigerated transport truck. From: author.

Figure 8 (right). Fish being transferred to rubber bag. From: author.

As the fish born at the Wells Dam salmon hatchery swim home each year, only as many as needed to mechanically spawn the next generation are used. The “hatchery extras” will have nowhere to spawn, due to the dams without fish passage that stand in the way. These “extras” come to the Colville Confederated Tribes, to be distributed equally throughout the membership as ceremonial food. The 30 mature Chinook swimming around in the truck’s climate-controlled tank will not be ceremonial food this year. They instead will embody a loving prayer to the river, in a ritual that unfolds before my eyes.

I do not know how to speak the Salish language, nor do I recognize with my mind the meaning of the words in the traditional songs that rise above the drumbeat. This does not stop my heart and my body from hearing the sound of love. The drum reverberates through me, pounding against the outside of my ribcage, awakening my heart, sending shivers of emotion down my arms and legs. The emotion is collective, and belongs to the people and the land they inhabit. It has been stirred awake by the pounding drum. The drum continues as the truck stops at the top end of the long line of people. Several men from the Colville Confederated Tribal fisheries department hop out.

Back in the 1940s, in the last months before Grand Coulee Dam was completed, non-Indigenous scientists scanned maps and rapidly devised a salvage plan for the salmon they knew would no longer have access to their natal streams above the dam. When the salmon arrived at the base of the dams, scientists captured the fish, loaded them into tank trucks and released them downstream, into the Okanagan River. There, they confidently proclaimed, the salmon would find new places to spawn. The otolith was overruled, and the plan morphed quickly to disaster. The trucks had no way to keep the salmon cool. Many were dead or dying by the time they arrived at the chosen river to be released. It was both an ethical and a scientific failure, one that snipped in two the sustainable cycle built over millions of years.

Over the half-century that followed this disaster, the tribes have gradually taken over supervision of hatcheries, exerting an ethics and sensitive awareness about how things are done. In doing so, they have begun to mend the connection between science and an empathic heart. Many people standing in the parallel lines hold two stones and knock them together, imitating the sound of shifting riverbed gravel. This sound, they say, would be familiar to any salmon traveling on a free-running river. They want the fish to feel welcome, and while they knock the stones, they pray for its homecoming.

The drums beat louder still as the net dips into the truck’s tank, bringing up the first silvery flash of a fish. The air thickens with emotion. The drum quickens as the fish goes head-first into a black rubber bag, half-filled with water. Tears well in my eyes. I hold my breath as the writhing bag passes carefully down through the two lines. Many hands graze against the bag as the fish moves rapidly through the assembled bodies. In a minute, or maybe two, the fish reaches the water. There, a strong young man helps a female elder lower the bag beneath the surface. The salmon pulses out and just as quickly darts away.

Figure 9. Salmon Rejoining Ceremony. Shared with permission from Peter Marbach’s (2019) Healing the Big River: Salmon Dreams and the Columbia River Treaty.

Around me three-hundred whoops of sustained joy rise up, filling the broad sky with love. This, I realize, is the voice of loyalty and memory. It is the voice of eros, a pure form of desire.

This Salmon Release Video provides a glimpse of the scene.

Over the next half hour, the drum beats each fish home, one at a time. I stand in the reservoir up to my knees, staying out of the way, watching. At one point, a salmon brushes against my calf before pulsing away into the shadows. I am unprepared for the erotic charge of this slippery skin brushing against mine. I watch in a distracted haze as more fish are released. The truck pulls away, empty. Women set out a breakfast feast on a few portable tables. I am not hungry, but I crouch on a piece of reservoir driftwood, forcing myself to eat. I have learned the importance of sharing food whenever tribal ceremony takes place. This is, I’ve been taught, a way to seal all the prayers offered up that day. After serving the food, tribal women circulate with gifts for all who attend, another offering that solidifies spirit.

Figure 10. Tribal women with gifts. From: author.

As I drive north again across the border to my Canadian home, I remain only half in this world. The next day, I have trouble rising from my bed, feeling pinned to it by the strength of the nearly impossible journey of that fish that had brushed against my calf. It seemed to have no fear on its way into the unknown. The 30 fish released that day, and the 30 to be released later in the week, may find each other, to school together. Viable spawning grounds exist within miles of where they have been released. But these 30 fish are not a biological experiment. Their release is a sacred moment, an act of faith.

What is the power of desire, in the face of the behemoth, rational economic engine of hydro-electric development? The knocking stones, the drums, the songs, the food – all loving prayers offered up to make a difference for the survival of those fish, those beloved darting off into the deep.

***

Several weeks later, at an international conference on the Columbia River Treaty in Kimberely B.C., I run into Leon Louis, a knowledge-keeper from the Lower Smilkameen Band in south-central British Columbia. I had last seen Leon at the re-joining ceremony. He is dressed neatly now as he was then: in a clean pair of jeans, a crisp cotton shirt and a beautiful, decorated vest. Around his neck hangs an intricately beaded medallion, positioned precisely over his heart. His immaculate blond cowboy hat shines on his head like a crown. We exchange pleasantries, after which I take the plunge.

Can I ask you a question, Leon?

Sure.

I describe the powerful emotions I had felt during the ceremony, the tears, the uncertainty and exhaustion the following day. He listens to the rush of my words, watching me carefully with his still and luminous eyes. I finish. I wait. His eyes continue to expand into dark pools of compassion. Finally, he speaks. Slowly, with long spaces between each sentence. These spaces fill with the shining depth of his understanding.

Yes. The spirits were strong that day.

I had not considered the presence of unseen spirits.

Seems like the Salmon Spirit must of brushed up against your spirit.

Nor had I considered this. That it was a fish, yes, but also embodiment. Of something else.

Don’t fight it. Go with it.

Tears well in my eyes as he walks away.

***

After my exchange with Leon, I realized how gratitude could support the emergence of a new order. Cradled within the Indigenous honoring of Salmon that I witnessed that day is a rich spiritual practice that can be adopted by anyone. What kind of world might emerge from more humble gestures of thanks such as those made by the tribes? Might the capacity for Salmon to hear and respond to sincere appreciation be limitless?

Sustainability is about more than achieving ecosystem balance, or designing moderate, careful use of resources. The word sacred is so rarely spoken in the non-secular, scientific world, where bright minds drive most conversations today about our planet’s future. The Latin root, sacrum, describes the bone that surrounds the human procreative organs. In order to walk upright as we move forward into the great change overtaking us, we can integrate reverence and gratitude for natural systems. An ancient and mysterious form of sacred love can keep us from stumbling, falling, or descend into bleakness

Editor’s note: Eileen Delehanty Pearkes is the author of A River Captured: The Columbia River Treaty and Catastrophic Change, a definitive history of the Columbia River Treaty and its social and ecological impacts in Canada.

Figure 11. A River Captured: The Columbia River Treaty and Catastrophic Change by Eileen Delehanty Pearkes. From: author.

Eileen Delehanty Pearkes is the author of A River Captured: The Columbia River Treaty and Catastrophic Change, a definitive history of the Columbia River Treaty and its social and ecological impacts. An American educated at Stanford University and the University of British Columbia, she has lived in Canada for three decades, where she writes about landscape and the human imagination.

Eileen Delehanty Pearkes is the author of A River Captured: The Columbia River Treaty and Catastrophic Change, a definitive history of the Columbia River Treaty and its social and ecological impacts. An American educated at Stanford University and the University of British Columbia, she has lived in Canada for three decades, where she writes about landscape and the human imagination.