Teiitooniine’etii: To Live Quietly, Live Calmly

Table of Contents: Place and Resilience in Sustainability Education, April 2016

Redman Redman Cohn JSE February 2016 Place Issue PDF

Hinono’ei-’: Place Where the Arapahos Are

Fig 1: Collage of student photos of Netniintoonoo, “our community” with Arapaho language descriptions.

Place, for the Northern Arapaho people, represents homelands for our Tribe: our place is our homeland. For many years we lived a nomadic lifestyle across the plains and into the Rocky Mountains; but before that, we migrated from the Great Lakes region due to pressures from colonists. All of these places are considered homelands by Northern Arapaho Tribal members. Each ancestral place holds part of our history in this land. For example, the plains where the buffalo roamed were our place because we used the buffalo for housing, food, and clothing; the mountains were our place because of the trees for our homes, medicines, and roots we gathered there. Our language remembers these locations. North Park, Colorado, is called heneecei-booo, (buffalo trail) and the Boulder area is hii3einoon niit-bii3ihi-3i hoh’eni, (buffalos, where they graze on the mountain). The Kawuneechee Valley in Rocky Mountain National Park is toh- ’okooxeee-ni’ (where we get tipi poles) and the Little Beaver River is honooxoehebiisi’-iini’ (there are bullberries there). These locations were ingrained in us as our places for safety, growth in the self and spirituality, and ways of surviving on this land.

Moving from our homelands in Colorado to the Wind River Reservation in Wyoming was another great transition for the Tribe. With this change Tribal members had to adjust from a nomadic lifestyle to one of settlement in one small part of our homelands against our wishes.

Resilience is the ability to recover from difficulty; being resilient is being able to live. The Northern Arapaho have overcome many trials through time here on earth. The biggest was when we were placed on the reservation. Regardless, this place in Wyoming offered shelter for the Tribe; our language and culture continue to give hope to each new generation that is born.

The elders and leaders of our Tribe have had discussions about what lies ahead for future generations and how they will put things in place so they may be able to navigate through these times. For many of us, stories from grandmothers and grandfathers tell us how to overcome adversity. They share knowledge of how our ancestors survived their struggles and how resilience strengthened them as people and benefited the Tribe.

Our community has created several programs to integrate this cultural knowledge into the public education system, since culturally responsive schooling has been shown to increase learning by building stronger connections between students’ school environment and their community. We believe that culturally responsive schooling is also important to our continued resilience as a people.

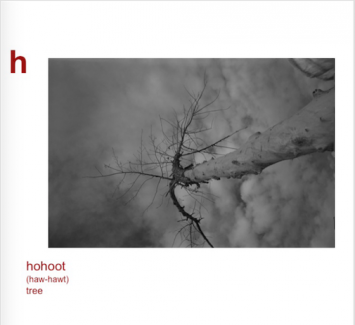

Picturing Place

When Tribal members began to understand the technology of photography, the camera became a fascinating tool for our community to capture images of family members, remember important events, and share our lives with distant relatives. But photography also helps us see the world differently through other generations’ eyes, and rephotography shows the way place changes over time. Photography—and its developing technologies—helps us teach our students the paradox that though place and culture endure, they both change over time. We offer three examples.

Netniintoonoo

The Netniintoonoo children’s photography project was part of the Arapaho Language Revitalization program at Arapahoe School. For several years, our culture program focused just on the Arapaho language, which is expected to last only 15 to 20 more years. The project was designed to create more classroom materials in Arapaho, and also to encourage students to see themselves as a part of our living language. Using black and white disposable cameras, students took pictures of people and places that were important to them; elders and language teachers then matched their pictures with Arapaho words they wanted the students to know. The project resulted in photographs and paired Arapaho phrases that were used in jigsaw puzzles, photo dictionaries, an exhibit and bound language books. The project also helped students to recognize themselves as a living part of their language, culture, community, and place.

Fig 2: Student images from an Arapaho language dictionary produced with student images of things they considered important about their community.

Arapaho language is critical to our people; it plays a vital role in place identity and self-identity. Through language, we access the cultural knowledge and ancient Tribal history that tells the story of the Arapaho people. Many of our words and stories—and the worldview they carry—do not translate into English because of the language structure itself. For example, the Arapaho language distinguishes animate from inanimate items. The word for a spoon, hebeiyoo, holds an animate form, meaning the spoon is alive. In our time following buffalo, spoons were made from buffalo horns, so the word still carries this animate history though our spoons are now metal or plastic; hebeiyoo still holds the respect and sense of place of this tool in our homeland. The language itself carries a memory of the Tribes’ journey and resilience. The language loss occurring on the Wind River Reservation will impact the Tribe’s future because future generations will not be able to access the same cultural knowledge and Tribal history in English. Language has held the Tribe strong through overwhelming changes. It carries stories of the attributes a person needs to overcome hardships and learn resilience. As one sixth grade student reflected, if the language were gone, “You never know, you might feel like something’s missing. Like part of you is missing.”

Rephotography

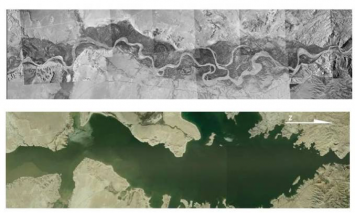

It’s important for our young people to know that just as language and people change, place changes, too. Lightning creates fires, for example, and burns our homelands. The heavy snows of 2010, and spring rain created floods that washed out bridges, shifted stream channels, and separated remote communities from one another. Additional changes in our homelands are human caused. For example, in 1950 the federal government removed over 25,000 acres of land in a “taking” from our reservation in order to create Boysen Dam.5 Cottonwood forests were inundated, invasive plants like Russian olive were introduced to stabilize banks, and our bottomlands changed forever. All along our rivers, cottonwoods and red willows are declining, which concerns the elders because these species are important for cultural events and ceremonies; we are called “Red Willow People” by other Tribes.

Fig 3: Aerial imagery of the Wind River before and after the inundation of Boysen Reservoir (1948 and 1949 georeferenced photo mosaic and 2006 orthophotos, USGS)

Additional landscape change relates to large-scale human impacts. Similar to glaciers, globally, the glaciers in our Wind River Mountains are melting, and we know that in years to come we will have less water in our rivers during late summer and fall. Northern Arapaho and Eastern Shoshone young people will manage our 2.2 million acres of mountains, rivers, and plains. It will be left to them to adapt to declining water supplies and a changing climate.

Fig. 4 Arapaho Glacier, the largest glacier in Colorado, 1898 and 2003. Located west of Boulder, in Arapaho homelands Photo courtesy of NASA.

In after school programs, and in science classes, we use repeat photographs to bring stories from the elders—images of what life was like back then—to the present. This type of sharing brings generations together to help revitalize language, values, and culture for the Northern Arapaho communities.

Fig. 5 Boysen Reservoir looking southward, prior to 1952 and 2007.

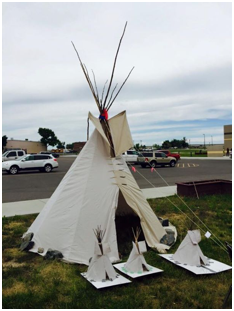

Tipis: 3D Printing

During STEM summer school, 2015, we took Arapahoe Middle School students on field trips to gather information about historical tipis. We measured tipi rings, collected tipi poles, and made mathematical projections about the heights of tipis and lengths of poles. Students developed a research question: What’s the ideal pole length for a tipi with a certain diameter? Once back at school, students were guided by culture teacher Mike Redman in assembling the tipi poles into a tipi frame. He asked: how do you think our ancestors knew what pole length worked, where to tie the poles together, how wide to place the poles? These essential questions helped students to access background knowledge: many students have helped set up tipi with their families or at school. Redman showed students how our ancestors measured with paces between the initial three poles then asked what shape it made: an equilateral triangle.

Students then designed tipis using different ratios with Tinkercad in computer labs, and printed replicas with a 3D printer. These mathematical connections show that through time Arapaho people used triangles and pole ratios in the construction of the tipi. By tapping into that knowledge through tipi construction, students were able to connect academic learning and centuries old cultural knowledge to help them bridge the two worlds.

Teiitooniine’etii

Teiitooniine’etii (to live quietly, live calmly) is a highly regarded value among Arapaho elders. A calm, quiet presence shows that you carry an awareness of your sense of place, a connection to life and community, and a sense of who you are as part of the Arapaho people. The frenetic pace of modern life is a concern for the elders. Moving quickly and loudly causes you to lose awareness, falls into chaos and out of balance.

In this article, we have chosen to focus on three examples of culturally-relevant school programs in our community. Each embraces increased technology, which may seem contradictory to teiitooniine’etii. Yet the Arapaho people have endured because we embraced change; we adapted to new technologies without losing our cultural values, knowledge of homelands, and sense of ourselves as a people. Place and culture endure; place and culture both change. In this paradox is our resilience.

Iva Moss Redman is an enrolled member of the Northern Arapaho Tribe and math teacher at Arapahoe Middle School. Her education research and practice involves culturally responsive math education, revitalization of Arapaho language, and support of Arapaho culture in both formal and informal education programs.

Iva Moss Redman is an enrolled member of the Northern Arapaho Tribe and math teacher at Arapahoe Middle School. Her education research and practice involves culturally responsive math education, revitalization of Arapaho language, and support of Arapaho culture in both formal and informal education programs.  Teresa Cavazos Cohn is a cultural geographer and Assistant Research Professor of Science Communication at the University of Idaho’s McCall Outdoor Science School. Her research focuses on Tribal water geographies and culturally responsive STEM education.

Teresa Cavazos Cohn is a cultural geographer and Assistant Research Professor of Science Communication at the University of Idaho’s McCall Outdoor Science School. Her research focuses on Tribal water geographies and culturally responsive STEM education.