Placemaking Curricula in Teacher Preparation: Bridging State Standards and Local Expertise

Link to the JSE General Issue May 2022 Table of Contents

Article PDF

Abstract: This study examined how placemaking curricula shaped teacher candidate (candidate) knowledge, dispositions, and skills to understand, appreciate, and sustain local diversity, as evidenced through candidate reflections and products created in an elementary teacher education course integrating civic science concepts and practices into elementary classrooms. This study explored how placemaking curricula engaged community stakeholders in meaningful shared inquiry on real-world challenges, while meeting state science education standards. Placemaking inquiry projects developed by candidates focused on soil and water conservation, and sustaining diversity in schoolyard spaces. Curricula engaged candidates in learning soil and water conservation techniques from local farmers and conservation leaders, then developing and sharing co-authored civic science children’s books on conservation topics aligned to grade-level standards. As further placemaking curricula, candidates partnered with elementary teachers and students to guide schoolyard observations, designs, and models constructed to sustain diverse abilities, cultures, and ecologies. Presentations to parents and peers celebrated shared insights.

Keywords: diversity, culture, ecology, sustainability, inquiry, placemaking, teacher education, standards

Introduction

This study examines how placemaking curricula shapes teacher candidate (candidate) knowledge, dispositions, and skills to understand, appreciate, and sustain local diversity, as evidenced through candidate reflections and products created in an elementary teacher education course integrating civic science concepts and practices into elementary classrooms. This study explores how placemaking curricula engages community stakeholders in meaningful shared inquiry on real-world challenges, while meeting state science education standards. Placemaking challenges addressed by candidates in this course include soil and water conservation, and schoolyard diversity and inclusion. Curricula engaged candidates in learning soil and water conservation techniques from local farmers and conservation educators, then developing and sharing their own co-authored children’s books on conservation topics aligned to grade-level content standards. As further placemaking curricula, candidates completed elementary school recess observations followed by group design, construction, and presentation to elementary students of their model schoolyards – sustaining of diverse abilities, cultures, and ecologies.

Examination of candidate learning for both projects included consideration for candidate ability to implement placemaking curricula in their own classrooms to guide the elementary students in developing knowledge, skills, and dispositions to understand, appreciate, and sustain diversity. Implications from this study consider how placemaking curricula offers potential to connect candidates and community stakeholders (e.g., public elementary school students and teachers, public librarians, farmers, and conservation advocates) in shared inquiry leading to meaningful local change. Placemaking curricula also open possibilities for greater local-global connectivity.

The research questions framing this study resonate with that of Power and Green (2014): “How can framing teaching through space and place inform pre-service teachers’ pedagogical thinking and practice?” (p. 105). The following questions guide this placemaking study:

- How does placemaking curricula in this study shape teacher candidate knowledge, dispositions, and skills to understand, appreciate, and sustain diversity?

- How does placemaking curricula in this study prepare teachers candidates to support elementary students in a similar learning process?

- How does placemaking curricula in this study engage community stakeholders in shared inquiry on real-world local challenges, while meeting state education standards?

Theoretical Perspectives

Placemaking

Cultural and Ecological Diversity

Placemaking research has examined the relationship between place and local change, particularly in regards to cultural-ecological justice (Anderson et al., 2016; Fettes & Judson, 2011), linguistic communities (Gonçalves, 2019), musical expression (Matsunobu, 2018), indigenous and non-indigenous knowledge (Carter, Hollinsworth, & Raciti, 2018), networking (Swist & Kuswara, 2016), and issues of discrimination (Butler, 2018; Turcatti, 2018). Recent placemaking research involved international communities in Australia (Carter, et al., 2018), Costa Rica (Armstrong, 2016), Japan (Matsunobu, 2018), Moroccans in the Netherlands (Turcatti, 2018), and South Africa (Rinquest & Fataar, 2016), among other studies in a quickly growing research field.

This work builds on previous placemaking pedagogies and studies connecting cultural and ecological sustainability as intertwined and central to sustaining localities around the globe (e.g., Anderson et al., 2016; Lawson, 2018; Lieflander, et al., 2013; Stahelin, 2017). Power and Green (2014) describe placemaking curricula as offering “a way to develop a more locally responsive education that acknowledges natural locales and their associated ecosystems as resources for learning” (p. 106). This study adds to the current research agenda connecting youth with local ecology (e.g., Lieflander, et al., 2013) by aiming to “remake schools [and, by extension, local communities]” (Comber, et al., 2009, p. 230) through shared teacher-community inquiry.

Bricolage as Transformative Inquiry

This study views inquiry as powerful for effecting transformation in communities and the individuals therein. The integration of inquiry into both placemaking projects recognizes research as a high-impact education practice (Kuh, 2008) for candidates, elementary students, and other community stakeholders. Community-based research places participant experience central to the development of inquiry questions and design. Research as a high-impact practice draws on primary resources, combines logic and creativity, partners stakeholders in meaningful design to address shared challenges and effect meaningful community change (Kuh, 2008).

Transformative inquiry (Iorio et al., 2017) positions researchers as bricoleurs, or brick layers, and encourages youth researchers to draw “from their lives to generate data” narrated as stories in which place is regarded as a “critical component” (p. 132). Transformative inquiry recognizes community funds of knowledge as educational resources (Moll, Amanti, Neff, & González, 1992). Building on the work of Moll et al. (1992), this study recognizes that cultures and ecologies include funds of knowledge to be appreciated and preserved. Comber et al. (2009) engaged a similar view in a study examining one school’s implementation of placemaking curricula, as students designed, negotiated, and re-developed a space between their school and a neighboring preschool. The curricula supported students in analyzing and re-producing space design, to participate in the political process of community transformation.

Bricolage as transformative inquiry engages cultural and ecological diversity to imagine and implement innovative placemaking pedagogies. This study is framed by transformative inquiry, taking an aesthetic approach to diversity and inclusion. Transformative inquiry aims to explore, understand, and represent diversity with appreciative regard, rather than analytical intent alone. It does not assume objectivity, but is aware of researcher blind spots (Hostetler, 2005).

Balancing Placemaking with Standards

This research takes place in an educational climate of accountability. Prominent education researchers view standards as foundational to professionalizing the field in the U.S. and abroad, while also recognizing that standards may be implemented without the necessary regard for context-based expressions of diversity and styles of learning (e.g., Darling-Hammond, 2005; Darling-Hammond, 2013; Darling-Hammond & Burns, 2017). Other researchers have questioned the implementation of standards in ways that demote professionalism in teaching. Teleshaliyev (2013) reflects on the tensions experienced by Kyrgyzstan teachers caught between Russian and Western versions of teacher professionalism demanded of them, and concludes that local teachers must lead teacher professional development in local contexts. Darling-Hammond (2005) highlights the importance of infusing teacher preparation and professional development with high quality standards internalized through meaningful community-based practices, such as “problem-based learning” with colleagues, rather than “one-shot workshops” (p. 23). Ostlund (2018) similarly highlights the vital role that professional learning communities (PLCs) have played in supporting Arizona K-12 teachers in integrating College and Career Readiness Standards in culturally and linguistically diverse communities. In response to the need for education practices to meet the needs of local communities where they are implemented, U.S. education and teacher education standards increasingly have articulated ways to support educators across levels and content areas in recognizing and supporting context-based diversity, including: state academic content standards, Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS), World-class Instructional Design and Assessment (WIDA), the Council for the Accreditation of Educator Preparation (CAEP), and Teaching English to Speakers of Other Language (TESOL).

Standards can be supportive and limiting. Standards may teach about recognized forms of diversity, while remaining blind to less recognized expressions of diversity. Standards may not account for the importance of local community-based innovation as vital to the cultivation of meaningful education and teacher education practices. Tensions between standards-based teaching and innovative local practice are held in balance by practitioners bridging the space between standardized institutions and evolving local realities. While top-down guidance has value, it cannot replace the bottom-up process of inquiry essential to any context-sensitive work. Transformative placemaking inquiry responds to standards while providing opportunity for locally-driven inquiry. Preparing teachers to guide students in this work entails that teacher candidates have the opportunity to experience locally-driven inquiry, themselves.

Prior placemaking research describes challenges in meeting required standards while implementing culturally and ecologically responsive curricula that engages community stakeholders and has meaningful local impact. Thomas’ (2005) research on a small rural school highlighted the importance of curricula connected to community identity, yet also articulated the pressures created by a “high-stakes educational climate” causing teachers at the school to feel “hard-pressed” to implement curricula meeting standards and recognized student needs. Thomas (2005) contends that rural school “longevity under standardized accountability may benefit from stronger academic ties to the community,” but that the “demands of the academic standards on teachers’ instructional practice may prohibit an instructional link to the community” (p. 23). If a community is not integral or recognized in the creation of standards, the voices within that community are at risk of being lost amidst the sound of the standardized norm. The standards likely will not reflect the cultural, ecological and other forms of diversity present in context.

Power and Green (2014) articulate implementing placemaking curricula in an undergraduate elementary teacher education program, such that notions of the “crowded curriculum” were “disrupted” (p. 115). Candidates learned to implement a “place pedagogy framework” without “increasing curriculum content,” but by “expanding curriculum possibilities” (p. 115). Power and Green (2014) also highlighted challenges met in trying to implement placemaking teacher preparation curricula, including some candidates being “talked out” of placemaking lesson plans by mentor teachers who told them it was “not really curriculum” (p. 115). Research is needed to explore how placemaking curricula in K-12 and teacher education interacts with standards, and how teachers might continue developing and implementing locally meaningful curricula.

This study examines how placemaking curricula shapes candidate, student, and community stakeholder knowledge, dispositions, and skills toward sustaining diversity via shared inquiry, and how such curricula can support students and candidates in meeting key standards.

Methods

This study engages mixed methodologies (Collins, Onwuegbuzie, & Sutton, 2006; Johnson, Onwuegbuzie, & Turner, 2005) by combining quantitative and qualitative research approaches. This process included deciding how to use a theoretical framework, collect and analyze the data, including the timing and priority of qualitative and quantitative analyses (Hanson et al., 2005). This QUAL QUAN mixed methods study draws predominantly upon qualitative findings complemented by quantified analyses of these findings. Qualitative data include candidate paper and digital children’s book topics, content and professional teaching standards met, sustainable schoolyard observation charts, design work, models, and presentations to elementary students, and interviews with partnering elementary teachers in 2019. Quantitative analyses of content and design trends in the qualitative data complemented the qualitative findings. Analyses focused on the Fall 2018 and 2019 implementations of the placemaking curricula as collaborative inquiry.

Data Sources

Study Site and Participants

The site for this study was an elementary teacher preparation course at a small, Midwest public university, including many first-generation college students. The placemaking curricula involved a local farm visit in collaboration with the owner, who also was the watershed coordinator for the county soil and water conservation district. All participating teacher candidates (candidates) were third-year undergraduates in a program that required prerequisite performance in the first two years of college. As a result, most of the participating candidates identified and performed as strong students. This course took place in the first year of the program and focused on methods of instruction for integrating science and social studies into elementary classrooms. Participating candidates in Fall 2018 included two sections of 18 and 16 candidates. Of the 34 candidates, 16 identified as white female, one female having a Latina background, and three as white male. The Fall 2019 course included two sections of 14 candidates, including 27 candidates identifying as white females, one female as having a Latina background, and no males. The initial Fall 2017 course included 20 candidates: 16 white females, one having a Latina background, and three white males. Dialogue during the farm visit revealed that about half of the 2019 participants had experience living on farms or had family members or friends who had lived on regional farms.

The participating in-service elementary teachers included four white females at two elementary schools: two 3rd grade classrooms at one school, and two 4th grade classrooms at another. Both classrooms generally reflected the demographics of the schools in which they were set. Based on Public School Review data (2022), the 3rd grade classroom’s school included 30% of students receiving free lunch (42% in the state) and 10% of students received reduced price lunch (7% in the state). The school population identified as 92% white (68% in the state), 4% Hispanic (12% in the state), 3% two or more races (5% in the state), 1% Black (13% in the state), and no students identifying as Asian (2% in the state) or American Indian (less than 1% in the state). The 4th grade classroom was in the same state and region, and in a school including 24% of students receiving free lunch and 10% of students received reduced price lunch. The school population identified as 84% white, 7% Hispanic, 3% Asian, 3% two or more races, 2% Black, and 1% as American Indian. While demographic representation was similar across the candidates and the schools, demographics within the study do not reflect broader global, national, or state populations. This significant point is addressed in implications for future practice and research, particularly the need to expand this work to include the voices of more diverse populations.

Placemaking Curricula

This study describes and examines the candidate and community impact from two course placemaking assignments: Candidates’ (1) co-authored civic science children’s books on soil and water conservation and (2) group constructed sustainable schoolyard designs.

Placemaking Design of Instruction

The children’s book assignment involved visiting a local farm where candidates rotated through stations to learn soil and water conservation techniques presented by the host farmers and county soil and water conservation district representatives. Candidates worked in pairs to identify and study an academic text on one of the conservation topics presented, and then co-author a children’s book on this topic, aligned with education standards for the appropriate grade-level audience. Books were developed first in paper and then in two digital forms: one using the digital tool, storyjumper.com, and an author video recording using the Chromebook software Screencastify. The children’s books addressed Indiana Science and Social Studies standards and NGSS for grades K-3, and articulated learning outcomes met through reading the content. The books also included discussion questions at the beginning, middle, and end, to draw on students’ prior knowledge, check for understanding, and engage students in discussion and application of key concepts presented. Candidates shared their paper books at the local public library with 1st and 2nd grade elementary students, then shared the digital versions of their children’s books with the county’s soil and water conservation district’s online educational resources site.

For the sustainable schoolyard design assignment, candidates first observed one or more schoolyard recess periods at a public elementary school, typically where they were completing classroom observations for the semester. Their observations noted ways in which diverse abilities, cultures, and ecologies were included and supported on the schoolyard, and ways in which they may be included or supported more effectively or meaningfully. Candidates recorded three examples of each with an accompanying rough sketch for an innovative schoolyard design idea to enhance inclusion or sustainability of diverse abilities, cultures, and ecologies. Then, candidates came together in groups of 3-4 to share observations, note trends across sites, design and sketch a schoolyard model more inclusive and sustaining of diverse abilities, cultures, and ecologies. The candidates gathered recycled, repurposed, or natural items to construct a model.

In Fall 2017, the first year of implementation, candidates presented their group schoolyard designs to each other in class. In Fall 2018, the second year of implementation, the candidates presented their designs to elementary students visiting the university to offer their feedback on the designs as an ‘expert audience’ on schoolyard experiences. The students included two 3rd grade and two 4th grade classes visiting the university, including one elementary school serving mid-low SES populations and one elementary school serving mid-high SES populations. In Fall 2019, candidates partnered in lesson planning to individually lead their own small group of 4-5 3rd or 4th grade elementary students in gathering observational data, developing an innovative design, and building a model schoolyard sustaining of diverse abilities, cultures, and ecologies.

Findings

This study evidenced candidate engagement with placemaking curricula as resulting in the development of candidate knowledge, skills, and dispositions, in traditional and unique ways. Candidates evidenced growth in their knowledge related to Indiana State Science Standards and the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS), as documented in Table 1 and Table 2 for the Civic Science Children’s Book assignment, and 3 and 4 for the Sustainable Schoolyard Design assignment. Integral to this knowledge development, candidates developed skills related to each of these inquiry-based assignments taking a bricoleur (Iorio et al., 2017) approach to learning. Candidates’ dispositional growth involved recognizing local farms as curricular resources for ecological sustainability topics addressed in their classrooms, as well as learning to find their own voice in sharing this content more meaningfully as authors of their own children’s books. Funds of knowledge were affirmed for candidates who identified with farming spaces. Candidate dispositional growth through the schoolyard curricula included enhanced attentiveness to the diverse cultures and ecologies present in school spaces, and understanding for how to support this diversity through sustaining pedagogies. While this work was effective in local spaces, related future practice and research should connect students with broader global diversity.

Candidate Knowledge: Standards-Aligned Curricula

Both assignments addressed Indiana Elementary Generalist Science Standards 5.2 (social, cultural, ethical aspects of science); 5.9 (integrate use of state science standards); as well as Indiana Elementary Generalist Social Studies Standards 6.5 (characteristics of human and physical systems and interactions between human and physical systems); and 6.9 (integrate use of state social studies standards). In addition, the civic science children’s book assignment addressed 5.5 (relationships of organisms to each other and environment; key characteristics of factors effecting ecosystems and biomes), while the sustainable schoolyard design assignment addressed 5.6 (uses of natural and human-made materials and technology to meet human needs and solve problems; design of moving systems and simple mechanical devices). Standards 5.9 and 6.9 were addressed by inviting candidates to identify key concepts and content standards, develop content learning outcomes, and design a lesson plan to implement in presenting both the civic science children’s book and the sustainable schoolyard design to elementary students.

Both assignments also addressed Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS). The co-authored children’s books addressed NGSS K-ESS2-2 (construct an argument supported by evidence for how plants and animals, including humans, can change the environment to meet their needs); K-ESS3-1 (use a model to represent relationships between plants, animals, humans and the places they live); K-ESS-3-3 (communicate solutions that will reduce the human impact on air, water, and land), and in one case K-ESS3-2 (ask questions to obtain information about the purpose of weather forecasting to prepare for, and respond to, severe weather). The sustainable schoolyard design assignment addressed NGSS 3-5-ETS1-1 (define a simple design problem reflecting a need with criteria for success, constraints on material/cost) and 3-5-ETS1-2 (generate and compare multiple solutions to a problem). Course curricula familiarized candidates with the different types of standards and processes for selecting standards to address in teaching.

In addition, both assignments addressed Indiana Developmental Standards for Elementary Educators 2.3 and 2.4 (roles of play, social interaction, hands-on experiences, and supportive interactions to support children’s learning); 2.8 (engaging students in generating and evaluating new ideas, problem solutions, and original work). The schoolyard design assignment additionally addressed the Indiana Developmental Standards for Elementary Educators 1.3, 1.4 and 1.5 (knowledge of typical developmental challenges; types of student diversity and exceptionalities; and the ability to use this knowledge to promote learning and development).

In regards to key concepts involved the sustainable schoolyard assignment (ability, culture, and ecology), the cooperating 3rd grade teachers reflected that students “did not know any of those words going into it” and “by the end, they knew the words.” One noted that while students “were presenting, they were using the words … I was just happy with the way all of it turned out. On the last day, I said to the other teacher, if we are offered this next year, we are totally doing it.” A cooperating 4th grade teacher reflected on the schoolyard design assignment that it provided opportunity to meet required state science engineering standards, while allowing students “real creative freedom” which “they loved.” This teacher reflected that the simple guidelines for design work aligned to three core concepts and supported students in coming up with “a lot of unique ideas,” and that she “did not notice anybody getting stuck.” Rather, “they embraced it.”

Candidate Skills

Paper & Digital Children’s Book Creation

Children’s book creation served as a valued tool for candidates, students, and teachers in sharing and discussing sustainability topics. This study highlights the value of authoring books in shared inquiry on sustainability topics, both at the candidate and elementary student level. The Fall 2018 implementation of the assignment included creating both paper and digital books, while the Fall 2017 implementation only involved paper book creation. The findings demonstrated that paper books provided a more personalized touch to the learning process, while digital books catered to students more engaged by online learning, and enabled reaching a broader audience online.

In the 2018 book creation process, 17 of 32 candidates preferred paper design, while nine preferred using digital tools and six preferred having both paper and digital book design options. In planning to implement children’s book creation to teach sustainability topics in their own elementary classrooms, eight candidates preferred to use paper and six planned to use digital tools, while 13 hoped to use both paper and digital book creation tools with students. Candidates preferring paper books appreciated the freedom offered by paper tools, and the greater accuracy that such tools enabled in conveying academic content. Candidates preferring digital books appreciated the pre-packaged story images and other options provided by digital book creation websites. The candidates reflected that elementary students who are less artistic may be able to focus on academic content more effectively when using digital book creation websites. The candidates preferring both paper and digital use reflected on the value of introducing technology tools to students, while allowing more artistic youth to be expressive with the paper tools.

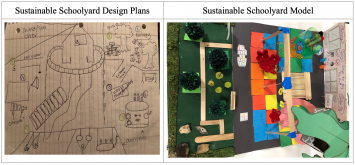

Sustainable Schoolyard Designs

Across all three cohorts, candidates initially articulated hesitancy in designing and developing a sustainable schoolyard model out of recycled and repurposed materials. Yet all three cohorts accomplished this task, effectively. The first Fall 2017 implementation of this assignment involved peer presentations only. To make the presentation more meaningful and the feedback more relevant, the second implementation of this assignment in Fall 2018 involved presenting and discussing schoolyard designs with visiting elementary students on the university campus. In this presentation, candidates led students in a lesson plan guiding their own design of sustainable schoolyard sketches. By leading elementary students in their own design work, candidates had the opportunity to apply theory to practice in implementing placemaking curricula for future practice. A third Fall 2019 implementation of the assignment involved candidates going to elementary school classrooms to co-design and create sustainable schoolyards with elementary students, who could apply their ideas to design work. Leading students in this work led to even greater intimidation at the start, yet concluded in shared student-candidate accomplishment.

The Fall 2019 design work was followed by interviews with collaborating teachers, who reflected that the project engaged students in meaningful cooperation and communication. One 3rd grade teacher reflected candidly about initially being unsure at the first implementation of the schoolyard project: “I knew they would love to build, I just did not know if it would be what they were supposed to be doing. The candidates really helped to guide them.” One 4th grade teacher reflected, the “planning step of the 2D model and next step to make the 3D model was powerful. The hands-on part of it was huge for students. Students loved it and were enthusiastic. Spatial 3D learning. Students strong in engineering skills had the opportunity to shine, even if not real book strong.” This teacher shared that one student with autism previously had trouble engaging in group work. Yet, he enthusiastically participated in the creation and presentation of his group’s model. The student internalized understanding of his Focus Group concept, ecology, much more effectively, than if he had read about the concept and memorized a definition. His individual funds of knowledge were engaged through his natural giftedness in using his hands to learn. This teacher noted that his mom attended the group presentations and left with a glowing smile.

Candidate Dispositions

Farms as Primary Sources, Candidates as Authors

This study evidenced candidate engagement with placemaking curricula as resulting in: (1) recognition of farms as primary knowledge sources for academic content on ecology-related topics; and (2) candidate recognition of themselves as authors in creating children’s books to share with elementary students. The Fall 2017 implementation asked candidates to choose any ecological sustainability topic of choice. This led to a variety of topics discussed (e.g., bird species, seed germination, flooding), while the majority of the books focused on pollution and recycling. Most candidates did not include key concept definitions or state standards met in their books, and no books included learning outcomes reached or discussion questions to check for comprehension, as these were not required. This assignment engaged candidates in learning varied environmental content, with limited connection to grade level education standards, and only engaged the community by reading books to elementary students in the public library.

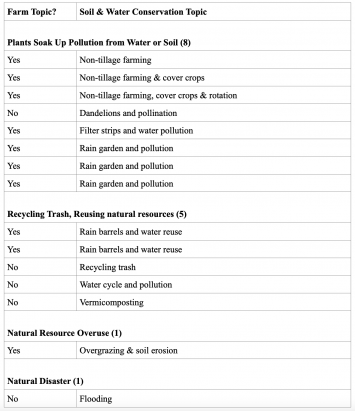

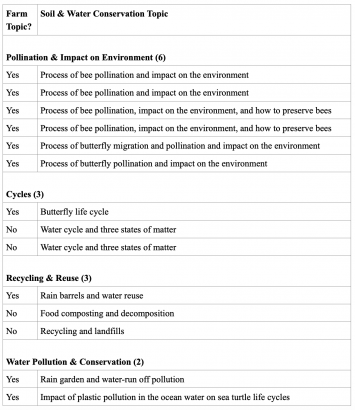

The revised Fall 2018 assignment engaged candidates in learning on farms, from farmers and local conservation educators about soil and water conservation, through five demonstrations on: non-tillage farming, cover crops, water barrels, filter strips/rain gardens, and overgrazing. The candidates had the freedom to focus on a topic of their choice. After visiting the farm, 10 of 15 books focused on a topic presented during the farm visit. (See Table 1). Seven of these 10 books focused on plants soaking up pollution from the soil and water through rain gardens, filter strips (see Appendix A), or cover crops on non-tilled farm fields. Two of these 10 books focused on rain barrels and water reuse. One of the books focused on overgrazing and soil erosion. The five candidate books that focused on topics not discussed during the farm visit included: dandelions and pollination, trash recycling, vermicomposting, the water cycle, and flooding. Candidates internalized their topics on a deeper level by co-authoring their children’s books to share. Co-authorship helped to ease any candidate hesitancy and promoted courage in this creative work.

In the Fall 2019 course, nine of the 14 co-authored children’s books focused on a topic presented in the farm visit. (See Table 2). The 2019 farm presentation added pollination and the ecological importance of pollinators. Six of the 14 books focused on the process, impact, and conservation of either bee or butterfly pollination. Two of these books focused on the use of rain gardens and rain barrels in response to water run-off pollution, the most written about topic of focus from the Fall 2018 farm visit. One 2019 book focused on the butterfly life cycle, discussed in the farm visit. Book topics not discussed on the farm include the impact of plastic pollution on ocean life, the water cycle and three states of matter, food composting, and the importance of recycling.

Conceptions of Schoolyard Diversity

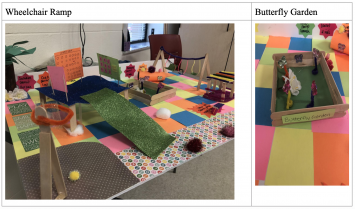

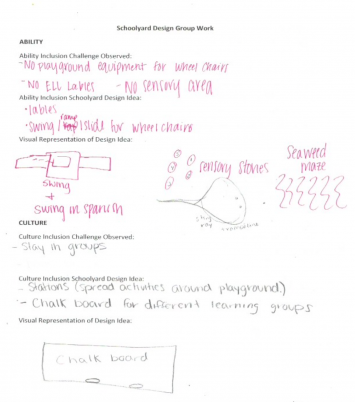

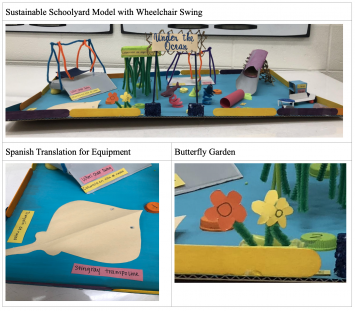

Small group sharing and discussion of individual schoolyard recess observations guided the design work (See Appendix B and C). This study found the Fall 2018 candidates most readily conceptualized diversity in terms of ability, evidenced in 20 ability-related innovations across eight sustainable schoolyard designs, particularly different forms of wheelchair access (14), including a wheelchair swing (6), platform or ramp (3), accessible playground mat (2), merry-go-round (1), picnic table (1), and basketball hoop (1). This study found that candidates worked to integrate cultural diversity in designs, as evidenced by 17 culture-related schoolyard innovations. Candidates most readily conceptualized cultural diversity in regards to language, as seen in 10 of these innovative design ideas. Language diversity was included through labeling playground equipment in English and Spanish (3), a multilingual entry/exit or language wall (4), hopscotch (1), and foursquare (1). Beyond language, a world map (3), international flags (1), and global music (1) were culture-related design ideas, as well. Candidates included design ideas supporting ecological diversity (17), and conceptualized ecological diversity most consistently as planting trees or flowers around the schoolyard (5) and creating a butterfly garden (4). In addition to these trends, unique ideas included adding native animal tracks to the playground (1), and designing playground equipment to resemble a butterfly life cycle (1). Content for these ideas had been part of course curricula. (See Table 3 and Appendix B, C, and D sample schoolyard design work.)

The 2019 Sustainable Schoolyard Designs co-developed by candidates with small groups of elementary students were more numerous across roughly 100 students. While specific design innovations were not counted, the following elements were present across multiple designs, with innovations ordered with the most common ones at the top of each diversity type listed.

Sustainable schoolyard designs created in 2018 and 2019 evidenced creative innovations for inclusion and sustaining of diverse abilities, cultures, and ecologies. Yet, Fall 2018 candidate presentations evidenced need for diversity conceptions to broaden, particularly so candidates might recognize and integrate in curricula diversity conceptions within and beyond their own school context. Candidate presentations demonstrated inclusion of diverse abilities (“including ways for all children to have equal access”) and ecologies (“the relationship between living things and their environment”). Yet candidate conceptions of culture were narrow in focus (e.g., “speaking a different language”) or so broad that context seemed irrelevant rather than central (e.g., “the way that a group of people live and interact with each other”). Some candidates evidenced a lack of identification with ‘diversity’ as something ‘others’ had. In one small group candidate presentation to students, a third grader of part Latino background asked, “So, am I diversity?” This candid question evidenced gaps in how candidates were understanding and representing the concept of diversity in their schoolyard presentation to their elementary student audience. The 2018 presentations evidenced need for future assignments to provide candidates with more information about and opportunities to research and experience diversity as complex and multi-faceted – specifically, as broader than their own backgrounds and prior experiences, AND as integral to their own unique cultural contexts and sociocultural identities.

The Fall 2019 implementation took place in elementary school classrooms, which cultivated more contextualized conceptions and discussions of diversity. Collaborating classroom teachers were able to coach students and candidates by offering a listening ear and reflective questions, coaching the small groups to see and support diversity in new ways. Candidates first worked in pairs to develop lesson plans, and then individually lead small groups of 4-5 elementary students. First, Focus Groups gathered observational data during recess on one of three topics: ability, culture, or ecology. This allowed each candidate and each student group to learn, understand, and observe one form of diversity, and then share their new understandings and observations in their Home Groups. Focus Groups discussed gathered data, including schoolyard components that supported diversity within their focus area, and absences or challenges to sustaining diversity. Candidates reflected on their roles in guiding and learning from student discussions, as student groups sketched innovative design ideas to support and sustain diversity in their focus group area, for their particular schoolyard context. Home Groups, composed of at least one member from each Focus Group, were tasked with sharing Focus Group ideas, and to design and construct a sustainable schoolyard model, using recycled or repurposed items.

Candidates in 2019, like candidates in 2017 and 2018, expressed feeling unsure about how to attempt construction of a schoolyard design, and how to lead elementary students in this work. In contrast, students were ecstatic to begin the effort, and counted the days until they jumped into the task. Final creations were creatively impressive and intellectually driven. Each sustainable schoolyard model was unique. Student groups proudly presented to student audiences for “expert feedback” on design ideas and construction, including 4th graders presenting to 5th graders at one school, and 3rd graders presenting to Kindergarten students at another. After the presentations, the mentor teachers discussed future collaborations that could involve funding to implement student ideas in redesigning their own schoolyard, or the playground space of a lower income school or public park. Dreams were shared about implementing this project in collaboration with an international school in a lower income global region to support peers in their own re-design work. In future implementations, more time may be needed to support candidates in building confidence in leading small group work. Yet, the final products — co-created by candidates and students for the first time — became a valued effort by students, teachers, and candidates, alike.

Scholarly Significance

Teacher Knowledge & Skills: Practice Placemaking Curricula Aligned to Standards

This study examines the practice of developing and implementing placemaking curricula in elementary teacher education. Placemaking curricula engages the perspectives and practices for understanding, valuing, and sustaining forms of diversity to develop “a more locally responsive education” (Power & Green, 2014, p. 106). This study builds on Moll et al.’s (1992) funds of knowledge framework to recognize that a region’s diverse cultures, ecologies, and abilities contain embedded insights and understandings to appreciate and preserve. Findings suggest that future curricular implementations integrate more opportunities for candidates to learn about and practice placemaking curricula focused on specific grade-level standards and concepts that drive curricular development, while engaging students in place-based learning. The implementation of placemaking curricula is more effective when carefully aligned with grade-level state content standards, and when candidates are reflectively aware of key professional standards for teacher education that they are meeting, as a result of designing and implementing such curricula.

This study imagines, enacts, and evidences ways in which placemaking curricula can positively shape candidate knowledge, skills, and dispositions to be more understanding, appreciative, and sustaining of diversity. By first working on their own intellectual, dispositional, and skill-based growth, candidates are prepared to lead elementary students in a similar developmental learning process, more meaningfully. This study describes how community-based partnerships with key stakeholders – e.g., elementary students, teachers, public librarians, local farmers, conservation advocates – to engage in shared inquiry focused on transformative community impact. This study regards ecology itself as a key stakeholder shaping the abilities and cultures of a given place, similar to the view of ecology in the student-led school space re-design in Comber et al.’s (2009) study. In contrast to Power and Green’s (2014) study in which mentor teachers initially supported and then questioned placemaking curricula, mentor teachers in this study welcomed collaboration with candidates in the course to implement placemaking pedagogies, and suggested a more developed collaborative partnership between students and candidates in the next year.

Teacher Dispositions:

Engage Funds of Knowledge & Expand Diversity Conceptions

The design and impact of the placemaking curricula in this study engaged candidates in recognizing the funds of knowledge (Moll et al., 1992) in their own community, specifically the valuable knowledge and perspectives to glean from local farmers, public librarians, elementary students, and practicing teachers. This curricula immersed candidates in the spaces frequented by the sources of their learning, specifically at a local farm, a public library, and a public elementary schoolyard. Placemaking curricula and research recognizes cultural and ecological connections in sustainability work (Anderson et al., 2016; Lawson, 2018; Lieflander, et al., 2013; Stahelin, 2017). This recognition values contexts as containing embedded knowledge and understandings that cannot be internalized without time spent in those spaces themselves. Parallel to Moll et al.’s (1992) funds of knowledge, by being in the contexts of recognized sources of knowledge (e.g., farmers, students, etc.), candidates send a vitally important message: the knowledge offered by this context and its community members is valuable. Dignity is affirmed by making it a priority to go and be in these spaces, and to learn from them. Context is a bridge for affirming dignity and knowledge when the effort is made to go to these spaces as part of teacher education.

After elementary students and teachers were invited to the candidates’ university campus, the collaborating teachers invited the candidates to come to their school sites the following semester in Fall, 2018. The K-6 students and teachers expressed feeling welcomed in the university setting and invited the university candidates into their own setting, to co-build sustainable schoolyard designs together. Sharing context in person through site visits provided opportunity to confer dignity and respect. Crossing borders is both strategy and outcome in placemaking curricula.

In addition to engaging local funds of knowledge, this study also encourages expanding conceptions of diversity held by candidates, and ultimately by elementary students, as well. This study encourages future implementations of this placemaking curricula to support candidates in conceptualizing diversity beyond their own local contexts or prior schooling experiences. Regard for intercultural and international localities is foundational to placemaking work, whether due to linguistic diversity (Gonçalves, 2019), indigenous knowledge (Carter, et al., 2018), or groups migrating to new settings (e.g., Matsunobu, 2018; Rinquest & Fataar, 2016; Turcatti, 2018). Candidates and elementary students might co-author civic science children’s books and co-design sustainable schoolyards that integrate inter-regional and international experiences of diversity — ecosystem and schoolyard diversity. Candidates and students might research these together to consider civic science narratives to share and innovative approaches for design work. As broader conceptions of diversity are engaged, this study encourages affirming community funds of knowledge in the candidates’ and students’ local context, as seen in this study.

Conclusion

Inquiry-based learning and partnership with community collaborators were central to both the civic science children’s book and the sustainable schoolyard design assignments. Engagement beyond the classroom to have a meaningful community impact is foundational to placemaking curricula. For the civic science children’s book assignment, candidates positioned farmers as sources of community knowledge by visiting a local farm and dialoguing about soil and water conservation challenges and practices to author a children’s book and accompanying elementary lesson plan to be shared in a public library with elementary students. Partnering elementary teachers offered feedback on book content and lesson implementation. For the sustainable schoolyard design assignment, candidates partnered with local schools to gather data during a schoolyard recess observation, collaborated with peers in small groups to design and build sustainable schoolyard models. In the second year, designs were presented to elementary students and teachers, who offered feedback as schoolyard experts. In the third year, candidates and elementary students co-developed schoolyard designs together. This study concludes that candidate-student-teacher-faculty collaboratives, as PLCs (Darling-Hammond, 2005; Darling-Hammond, 2013; Darling-Hammond & Burns, 2017; Ostlund, 2018; Teleshaliyev, 2013), is an effective context for implementing standards in meaningful ways, and vital to ensuring that expressions of local and global diversity and funds of knowledge are embedded in curricula and instruction preparing future glocal citizens (Liu & Ye, 2019).

References

Armstrong, C.M. (2016, May 15). “Don’t step on the ants!” Biomimetic pedagogy for sustainability in a Costa Rica study away experience. The Journal of Sustainability Education. Retrieved at http://www.jsedimensions.org/wordpress/content/dont-step-on-the-ants-biomimetic-pedagogy-for-sustainability-in-a-costa-rica-study-away-experience_2016_05/

Butler, T.T. (2018, March). Black girl cartography: Black girlhood and place-making in education research. Review of Research in Education, 42(1), 28-45.

Carter, J., Hollinsworth, D., & Raciti, M. (2018). Academic ‘place-making’: Fostering attachment, belonging, and identity for indigenous students in Australian universities. Teaching in Higher Education, 23(2), 243-260.

Comber, B., Nixon, H., Ashmore, L., Loo, S., & Cook, J. (2006). Urban renewal from the inside out: Spatial and critical literacies in a low socioeconomic school community. Mind, Culture and Activity, 13(3), 228–246. doi: 10.1207/s15327884mca1303_5

Collins, K.M.T., Onwuegbuzie, A.T., & Sutton, I.L. (2006). A model incorporating the rationale and purpose for conducting mixed-methods research in Special Education and beyond. Learning Disabilities: A Contemporary Journal, 4(1), 67-100.

Darling-Hammond, L. (2005, December). Prepping our teachers for teaching as a profession. Phi Delta Kappan, 22-27.

Darling-Hammond, L. (2013). Getting Teacher Evaluation Right: What Really Matters for Effectiveness and Improvement. New York: Teachers College Press.

Darling-Hammond, L., & Burns, D. (2017). Empower Educators: How High-Performing Systems Shape Teacher Quality around the World. Hoboken, NJ: Jossey-Bass.

Fettes, M., & Judson, G. (2011). Imagination and the cognitive tools of place-making. The Journal of Environmental Education, 42(2), 123-135.

Gonçalves, K. (2019). YO! or OY?– Say what? Creative place-making through a multilingual artifact in Dumbo, Brooklyn. International Journal of Multilingualism, 16(1), 42-58.

Hanson, W.E., Creswell, J.W., Plano Clark, V.L., Petska, K.S., & Creswell, J.D. (2005). Mixed methods research designs in counseling psychology. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52(2), 224-235.

Johnson, R. B., Onwuegbuzie, A. J., & Turner, L. A. (2005, April). Mixed methods research: Is there a criterion of demarcation? Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association, Montreal, Canada.

Kuh, G.D. (2008). High-Impact Educational Practices: What They Are, Who Has Access to Them, and Why They Matter. Washington, D.C.: Association of American Colleges & Universities.

Johnson, P. (2013). Schoolyard geographies: The influence of object-play and place-making on relationships. Review of International Geographical Education Online, 33(1), 77-92.

Lawson, N.L. (2018). Doorway to wonder: Charting new environmental education and place-making pathways in urban Los Angeles. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). UCLA, Los Angeles, CA.

Lieflander, A., Frohlich, G., Bogner, F., & Schultz, W. (2013). Promoting connectedness with nature through environmental education. Environmental Education Research, 19(3), 370–384.

Liu, L.B., & Ye, J. (2019). Ren-De agency in international faculty professional development: A China case study of glocal identity integration. Teacher Development: An International Journal of Teachers’ Professional Development, 23(4), 447-468.

Matsunobu, K. (2018). Music making as place making: A case study of community music in Japan. Music Education Research, 20(4), 490-501.

Moll, L.C., Amanti, C., Neff, D., & González, N. (1992). Funds of knowledge for teaching: Using a qualitative approach to connect homes and classrooms. Theory into Practice, 31(2), 132-141.

Power, K., & Green, M. (2014). Reframing primary curriculum through concepts of place. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 42(2), 105-118.

Public School Review. (2022). Csa Lincoln Campus. Retrieved from https://www.publicschoolreview.com/csa-lincoln-campus-profile

Public School Review. (2022). Rockcreek Elementary School. Retrieved from https://www.publicschoolreview.com/rockcreek-elementary-school-profile

Rinquest, E., & Fataar, A. (2016). The ‘affective placemaking’ practices of girls at a high school in Cape Town, South Africa. Educational Studies: Journal of American Educational Studies Association, 52(6), 521-535.

Stahelin, N. (2017). Spatializing environmental education: Critical territorial consciousness and radical placemaking in public schooling. Journal of Environmental Education, 48(4), 260-269.

Swist, T., & Kuswara, A. (2016). Place-making in higher education: Co-creating engagement and knowledge practices in the networked age. Higher Education Research and Development, 35(1), 100-114.

Teleshaliyev, N. (2013). “Leave me alone – simply let me teach” An exploration of teacher professionalism in Kyrgyzstan. European Education, 45(2), 51-74.

Thomas, T.G. (2005). Teachers’ decision-making about place-based education and state testing. The Rural Educator, 26(3), 19-24.

Turcatti, D. (2018). The educational experiences of Moroccan Dutch in the Netherlands: Place-making against a backdrop of racism, discrimination and inequality. Intercultural Education, 29(4), 532-547.

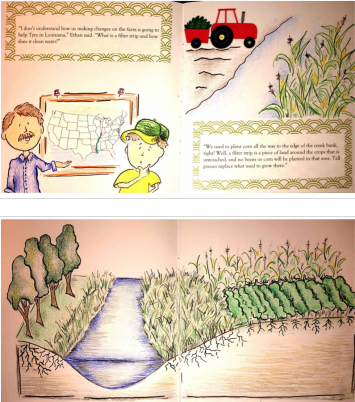

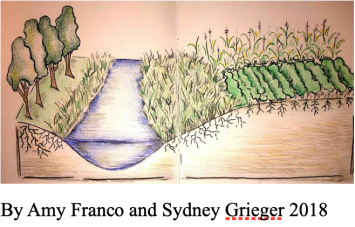

Appendix A

2018 Children’s Book

Civic Science Children’s Book on Soil & Water Conservation: Filter Strips. Book by Amy Franco and Sydney Grieger, 2018.

Appendix B

2018 Sustainable Schoolyard Design

Appendix C

2018 Sustainable Schoolyard Design

Appendix D

2018 Sustainable Schoolyard Design

Sustainable Schoolyard Design by Kaylynn Jones, Hannah Everhart, Shannon Belcher, and Cheyenne Dean, 2018

Laura B. Liu is Assistant Professor and English as a New Language Program Coordinator in the Division of Education at Indiana University-Purdue University Columbus. Laura integrates arts-based inquiry into her teaching and research, which is shaped by three primary lines of inquiry: glocalization, diversity sustaining pedagogies, and teacher/faculty professional development.

Laura B. Liu is Assistant Professor and English as a New Language Program Coordinator in the Division of Education at Indiana University-Purdue University Columbus. Laura integrates arts-based inquiry into her teaching and research, which is shaped by three primary lines of inquiry: glocalization, diversity sustaining pedagogies, and teacher/faculty professional development.