Koalas – Agents for Change: A case study from regional Victoria

Link to the General Issue February 2022 Table of Contents

Schlagloth et al JSE General February 2022 PDF 2

Abstract: We investigated the success of the Koala Conservation and Education Program, conducted in Ballarat, Victoria, Australia from 2000-2009 by interviewing 28 individuals, from various stakeholder groups involved in the project. Transcripts were analysed using grounded theory to identify common themes, keywords and phrases. We conclude that the chosen ‘flagship’ species, the koala, was crucial for the success of the project which culminated in the adoption of the Koala Plan of Management and habitat overlays into the City of Ballarat’s planning scheme. Local people were concerned about the koala based on its conservation status nationally and globally rather than because of its local or Victorian status. We conclude that the concept of ‘flagship’ species in the case of the koala, is more a global than a local construct.

Keywords: Koala, flagship species, community education, community engagement, environmental awareness, community spirit.

Introduction

Koala populations are declining across the species’ range along the east, south-east coast of Australia (Department of Environment and Energy, 2016) including in many areas in mainland Victoria due to habitat loss and fragmentation, collisions with cars, dog attacks and disease (Phillips, 2000). In some areas in Victoria over-browsing of Eucalyptus trees is occurring, particularly in forest fragments and on islands, where koalas have been introduced or re-introduced since the 1900s. There is evidence that this decline is threatening the species’ long-term survival (Menkhorst, 2008; Whisson, Dixon, Taylor & Melzer, 2016). The Victorian State government considers koala populations as ‘stable’ (Biodiversity and Natural Resources Division Department of Sustainability and Environment, 2004), in contrast to Queensland, New South Wales and the Australian Capital Territory where the species is listed as ‘vulnerable’ (Department of Environment and Energy, 2016). A recent summary of the status of the koala in each of the Australian states and territories is included within Park and Roberts (2020, pp.2-4).

Despite the stable listing in Victoria, the Ballarat community’s concerns about the decline of koala populations in the region, led to the assignment of an Australian Koala Foundation (AKF) liaison officer to Ballarat in 2001 as part of its mission to engage in innovative and collaborative ways to protect koala habitat. This officer worked in conjunction with the City of Ballarat to establish a community education program underpinning the Koala Plan of Management (KPoM) with an ultimate aim of protecting koala habitat through the planning scheme. This endeavour progressed despite the lack of a legal requirement for the Ballarat City Council to introduce koala habitat overlays into its local planning scheme. Such requirements were encouraged but not mandated by the Victorian Government (Biodiversity and Natural Resources Division Department of Sustainability and Environment, 2004).

The community engagement project was initiated by the ‘Ballarat Residents: Koala Survey 2002’ whereby all ratepayers were surveyed to gauge community attitudes to koala protection (Schlagloth et al., 2004). As a result, over 100 presentations and activities were delivered to stakeholder groups. The project was extended until 2009 culminating with the City of Ballarat adopting the KPoM and introducing protective Koala habitat overlays into the urban planning scheme: a first for Victoria.

Whilst the KPoM was mainly designed to limit the impact of housing and road development on the local koala habitat, it was understood that the project might have flow-on effects for the conservation of other animal species dependent on mature open forests. The koala overlay on council’s planning maps was designed to guide developers towards implementing approaches limiting impacts on the forest environment. This process was supported by a whole-of-community approach which, initially, in part, was demonstrated by the feedback received and the results obtained from the Ballarat Residents: Koala Survey 2002 (Schlagloth et al., 2002). This whole-of-community approach involved the liaison officer engaging with a broad group of community groups and involving these in various aspects of koala conservation. Many hands-on activities such as tree plantings to re-establish koala habitat along previously degraded creeks were performed with different stakeholder groups. These activities were supplemented with educational sessions to explain the need for koala conservation and place them in the bigger picture of biodiversity conservation.

After the completion of the KPoM, another project called ‘Koala Connect’ (Municipal Association of Victoria), was funded through the Victorian Sustainability Accord to assess people’s attitudes towards the protection of biodiversity. Ballarat’s KPoM sought to educate the public about the need to protect koala habitat, including the development of resources and presentations to several community groups and schools.

‘Flagship species’ concept

Mills (2012, p.245) described flagship species as ‘… animals that are huge, ferocious, cuddly, cute, or of direct benefit to humans; they are the charismatic animals most likely to make people smile, feel goosebumps, and write a check for conservation.’ The concept assumes that raising the profile of a particular species encourages public support for biodiversity conservation. Examples include the giant panda (Ailuropoda melanoleuca) in China (Yang et al., 2018), the bison (Bison bison) in North America (Hammerschlag, & Gallagher, 2017) and the gorilla (Gorilla gorilla gorilla) in Congo (Breuer, Manguette, & Groenenberg, 2018). Whether flagship species hurt or help conservation remains contested (Moynes, Bhathe, Brennan et al., 2021). Veríssimo, Fraser, Bristol, Groombridge and MacMillan (2009) and the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act (1999) suggested that characteristics for determining flagship status are: population size, range, threatening processes and reproductive viability. Simberloff (1998) cautioned that identifying a flagship species might not be a suitable surrogate for broader biodiversity or ecosystem protection. He questioned what would happen if the flagship ‘sank’ (e.g., population decline or extinction) and if the public’s emotional investment in that flagship species could turn to disenchantment with conservation in general. Fleishman, Blair and Murphy (2001) suggested that once a flagship species became extinct, the survival of other species, or the environment in general, would become more challenging. Roberge and Angelstam (2004) suggesed that using selected species may elicit biased management and conservation priorities in its favour and be detrimental to more threatened, yet less appealing, species.

In Victoria, at the time, the koala conservation program began in Ballarat, Martin and Handasyde (1999) as well as Kelso (2001) suggested that the koala had received disproportionate interest relative to its conservation status and, undesirably, had become the focus of conservation managers. By 2020, Whisson and Ashman (2020) were acknowledging the importance of maintaining healthy populations of koalas in Victoria where they were relatively abundant, with approximately two thirds of Australia’s total koala population in southern Australia, and its population still declining throughout the koala’s northern range.

Dell’Amore (2009) proposed that promoting multiple iconic species would have a greater effect than single species. However, Barua (2011) raised the issue that the public may confuse flagship species with other terms, such as umbrella, keystone or indicator species, especially seeing that some concepts can have a similar meaning. She stated that misrepresentation of terminology is a major impediment to enhancing public conservation literacy, while others such as Leader-Williams and Dublin (2000) suggested that the vagueness of the term might also be its strength.

Koalas have potential as a flagship species because of their charismatic status and role in the Australian ecology (Siebuhr, 2000). Lunney, Esson, Moon, Ellis and Matthews (1997) and Schlagloth, Santamaria, Golding and Thomson (2018) recognised the value of emphasising the koala’s role as a flagship species, in enhancing conservation education and as an effective ‘agent for change’ and the need for such ‘agents for change’ as catalysts for action. However, there are only a few publications that focus on the koala as potential ‘flagship’ species or that evaluate stakeholder’s understanding of flagship species. The current research addresses this gap.

Method

This paper is a case study (Babbie, 2008) in which a phenomenological (reliance solely on personal experience) approach was employed (Seidman, 2013). We employ the use of narrative studies which focus on participants’ values (Riessman, 2008) and represent multiple perspectives on shared events (Burck, 2005; Davis, 2008). Convenience sampling, drawing from the population close at hand (Lavrakus, 2008), was used to invite 28 participants from various groups in the Greater Ballarat area to be interviewed about their experiences associated with the koala conservation program. We interviewed stakeholders from five groups: government, education, environment, community and business to participate in a 30-minute interview. If interviewees belonged to several stakeholder groups, they clarified which group they represented at the time of the interview.

All interviewees were asked five open-ended questions:

1) What do you understand were the objectives of the Koala Conservation Program in Ballarat 2001-2009?

2) What do you understand were the outcomes?

3) What factors do you think affected the outcomes?

4) What do you understand by the term ‘flagship’ species?

5) If we take your definition, in what ways was the koala a ‘flagship’ species in the context of this project (or not)?

Interviews were recorded and transcribed. Transcripts were analysed for common themes, key words and phrases using open-coding (Corbin & Strauss, 1990; Reinard, 2008). Thematic groups were identified and, with constant comparison, topics were developed based on participant responses.

Results and Discussion

During the interviews, most interviewees answered in narrative form offering views on what influenced their participation in the program. Table 1 below summarises participants’ views on common themes illustrated by key words and phrases.

| Common Themes | Keywords / Phrases |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table 1: Common Themes and Keywords / phrases from the Interview Transcripts

Analyses of transcripts identified four main themes: Community education, Community engagement, Furthering environmental awareness, and Protection of the koala and its habitat in Ballarat [see Table 1].

Interviewee responses were consistent with the previously surveyed evidence of relative community ignorance about the need for koala conservation and aspects of koala ecology, despite this being one of the main aims of the local project. However, interviewees also confirmed that one of the project’s objectives was to engage with communities and therefore they valued other projects such as the Koala Habitat Atlas for Mt Macedon [a reserve and town, 64 km north-west of Melbourne] and Golden Plains Shire [a local government area, adjoining the City of Ballarat to the south], and re-vegetation of some of Ballarat’s degraded creeks. The consensus was that the project had fulfilled its main objectives of mapping koala habitat and introducing habitat overlays into the Ballarat City planning scheme.

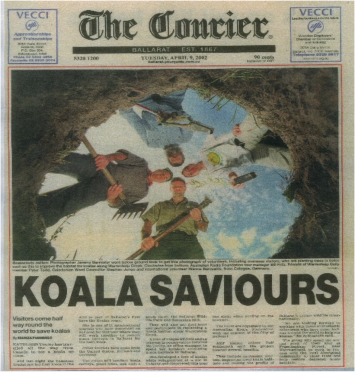

Interviewees identified that education and engagement of community were motivated and informed by presentations to diverse groups and hands-on activities. While we acknowledge that the link between knowledge and action is contested in the sustainability education literature (van Kerkoff & Lebel, 2008), in our case study, the community presentations and associated media coverage led to active community engagement. They also identified that success of the project was due to its community appeal and involvement of a range of people from the local population. Such engagement activities often involved multiple stakeholder groups simultaneously and received wide publicity. For example, a conservation group would collaborate with Ballarat City Council to revegetate koala habitat along a degraded creek while involving international koala tourists and local residents and school children.

Figure 1: Example of the community publicity generated during the Koala Conservation Project in Ballarat – Koala Saviours (The Courier – Ballarat, 9 April 2002)

Although Kelso (2001) warned of the disproportional attention, funding and research that the koala receives compared to other species which are under a greater threat from extinction, our findings suggested that stakeholders in the Ballarat Koala Conservation Project did not share this view. Instead, they fully embraced the koala as a flagship species. Resolutions to complex issues require transparency and therefore, public engagement in conservation efforts and policy formulation is considered desirable by many conservation professionals (Jordan, Gray, Howe, Brooks & Ehrenfeld, 2011). Effective conservation management is about listening to the community living with wildlife (Frank, Monaco & Bath, 2015).

The following paragraphs tease out the six common themes identified from the interviews that they identified as being the main reasons for the success of the project:

Leadership – interviewees identified that the co-operation of the City of Ballarat Council was central to the project’s success. This involved the personal commitment of a number of individuals and groups who assisted the progression of the project; however, the key theme was that individuals managed to work together towards a common goal creating the desired outcomes. Examples of phrases were: ‘I had lots of residents telling me this is a good project to support.’, ‘very visionary Councillors’ and ‘councillors who were pro-active.’

Community spirit – was valued. Ballarat is well known for its community spirit (Kelly, 1994; Rey Pérez & González Martínez, 2018) and this value was identified as an important factor that affected outcomes. Collier & Smith (2009) found that programms that motivate behaviour change need to be linked to the community’s views; concerns and understanding of the problems; use of a range of approaches that address ‘head, heart, hip-pockets’ and practical action for change targeting the interests of individuals, local community and specific groups of people. Examples of phrases were: ‘pressure and advocacy from the local community’, ‘the Mt Helen [locality 8kms south of Ballarat] struggle to protect its habitat perhaps emphasises that without this community koala campaign, the case of a KPoM would not have been as immediate’ and ‘a community that cares about its environment’.

Education of community members – was essential and partially driven by media, school and community group presentations. The koala as a flagship species was central to these presentations. This agrees with Lunney et al. (1997) who acknowledge that koalas are a suitable flagship to further environmental education for conservation. In addition, Cork, Clark & Mazur (2000) and Harris & Goldingay (2003) emphasise the need to apply an interdisciplinary effort for koala conservation. Examples of phrases were: ‘especially the media and educating the community’, ‘there were so many schools that benefited from presentations and other engaging projects’ and ‘our group, just like many others, benefited from the education provided as part of the program’.

Stars aligned; the right time, the right place, the right people – interviewees stressed the project’s success was serendipitous and an amalgam of people, timing and location. Examples of phrases were: ‘many things lined up at the same time that made this project work’, ‘the stars aligned for the project’ and ‘timing was perfect, many things fell into place at the right time’.

Flagship species – interviewees confirmed a general understanding of the term flagship species. They suggested that promoting the profile of a particular species generated support for conservation. As such we argue that flagship species can have a wider effect on environment issues becoming a symbol for environmental awareness program.

The focus on the koala as a flagship species was perceived as being essential in this project as evidenced by the phrases used by interviewees in response to Question 5, and as summarised in Table 2. A flagship species can represent an environmental feature (e.g., a species or ecosystem) or an environmental focus (e.g., climate change or ocean acidification). Bridie et al. (2008) identified that such species create connections to the historical, cultural and economic importance.

| Common Theme | Keywords / phrases |

| The koala was the essential flagship in this project. |

|

Table 2: Themes and keywords / phrases about flagship species from interviewee responses

The idea that the koala population in Ballarat at the time of the project was apparently secure did not preclude stakeholders from promoting a comprehensive education, awareness and habitat protection campaign that lasted for nearly a decade. Stakeholders celebrated the Koala as a suitable ambassador for conservation ignoring information about population size or its official conservation status as relatively secure in Victoria. This is in contrast to Veríssimo et al. (2009) who emphasise that an important characteristic for determining a flagship species is its conservation status, and that population size is a key determinant of conservation status. This did not apply in Ballarat. Stakeholders were concerned about the species without regard to population size, as the size of the local koala population was unknown, and the species was not officially listed as under any threat.

Schussler and Olzak (2008) and Marchbach-Ad (2004) describe the negative effects of a general bias of people for animals, and certain animals over plants, while Frazier (2005), points out that there is a danger of focusing on the ‘cute and cuddly’ aspect of a flagship species while neglecting research needed to assist the conservation of other species with more complex or specific requirements. However, it may be valuable to generate community empathy for a selected species as the vehicle for a grander, more comprehensive conservation agenda. In contrast, Simberloff (1998) warns that flagship species might not be good surrogates for broader biodiversity or ecosystem protection because there is the potential for the flagship species to disappear and public emotional investment to turn to disenchantment. Wang et al. (2021) also warn of the risk of using umbrella species as a conservation shortcut and diverting scarce funds toward a single charismatic species. Once a flagship species has disappeared, there is little hope for other species or the environment in general (Fleishman et al., 2001).

Regardless of the potential disadvantages that some authors see with the focus on one species, stakeholders were supportive of this approach as expressed by comments such as ‘the stars aligned’ and ‘many things fell into place at the right time’.

Conclusion

Stakeholders in the Koala Conservation Project in Ballarat understood that the ultimate aim was to prepare a KPoM for the City of Ballarat. This process introduced protective habitat overlays into the planning scheme. Stakeholders indicated that this aim was accompanied by a comprehensive community education, awareness and engagement campaign.

Interviews confirmed that stakeholders perceived the outcome of the Koala Conservation Project to closely match its objectives through the writing and adoption of the KPoM and the introduction of overlays into the planning scheme to achieve a level of protection of the koala and its habitat. This was achieved by increasing community environmental awareness programs associated with a successful community engagement campaign.

The koala was essential as the conservation or education flagship in this project. It appeared that people became engaged because of their personal affiliation with local populations and because they perceived that they were part of an important community initiative with positive conservation outcomes.

There were concerns that the momentum of the Koala Conservation Program may decline after it had achieved certain milestones, illustrated by the interviewee comment that ‘once the overlays had been adopted there wasn’t a lot of focus on enforcement and continuing the education process by council’. Therefore, we suggest that future research should be conducted over regular intervals to address such concerns; nevertheless, we argue that the public symbolism of the koala, as an iconic flagship species for Ballarat, as illustrated by the logo and words in Figure 2, will ensure that Ballarat indeed ‘Embraces the Koala’ and it has a secure local future.

We conclude that the koala as a flagship species, can be an effective ‘agent for change’. Our research has shown that there is the need for such ‘agents for change’ as catalysts for action. In coming to this conclusion, we acknowledge that the concept of the koala as a flagship in Ballarat has also been influenced by its wider global and national iconic status rather than just its local situation in the context of our own study.

We conclude that a flagship species such as the koala needs to be at risk to be effective as a flagship, but not be at so much risk that its survival is problematic. Nor should it be a species that is rare [because of population loss], uncommon [difficult to find], not exciting [beautiful, cuddly] and not likely to become extinct soon. People need to be convinced that their actions in relation to any flagship species will bring about a positive change within the foreseeable future. Flagship species need to have the potential for change with action by people who are inspired by positive case studies and who can see that their own involvement is being able to bring about that change.

Statement of authenticity: This manuscript is an original work that has not been submitted to nor published anywhere else.

References

Babbie, E. R. (2008). The basics of social research. Belmont, CA: Cengage Learning.

Barua, M. (2011). Mobilizing metaphors: The popular use of keystone, flagship and umbrella species concepts. Biodiversity and Conservation, 20(7), 1427-1440, DOI:10.1007/s10531-011-0035-y

Biodiversity and Natural Resources Division Department of Sustainability and Environment (2004). Victoria’s Koala management strategy. Melbourne: Government of Victoria.

Breuer, T., Manguette, M., & Groenenberg, M. (2018). Gorilla Gorilla spp conservation–from zoos to the field and back: examples from the Mbeli Bai Study. International Zoo Yearbook, 52(1), 137-149.

Bride, I. G., Griffiths, R. A., Meléndez-Herrada, A. A., & McKay, J. E. (2008). Flying an amphibian flagship: Conservation of the Axolotl Ambystoma mexicanum through nature tourism at Lake Xochimilco, Mexico. International Zoo Yearbook, 42(1), 116-124. doi:10.1111/j.1748-1090.2008.00044.x

Burck, C. (2005). Comparing qualitative research methodologies for systemic research: The use of grounded theory, discourse analysis and narrative analysis. Family Therapy, 27(3), 237-262. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6427.2005.00314.x

Collier, G., & Smith, P. (2009). Beyond lip service: A council approach to planning for behaviour change. Australian Journal of Environmental Education, 25(2009), 129-138.

Corbin, J. M., & Strauss, A. (1990). Grounded theory research: Procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria. Qualitative Sociology, 13(1), 3-21.

Cork, S., Clark, T., & Mazur, N. (2000). Introduction: An interdisciplinary effort for Koala conservation. Conservation Biology 14(3), 606-609.

Davis, E. M. (2008). Risky business: Medical discourse, breast cancer, and narrative. Qualitative Health Research, 18(1), 65-76.

Dell’Amore, C. (2009). Ten climate change “flagship” species named. National Geographic News. Retrieved from https://www.biologicaldiversity.org

Department of Environment and Energy (2016). Koala (Phascolarctos cinereus) listing. [webpage]. Retrieved from https://www.environment.gov.au/biodiversity/threatened/species/Koala

Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act (1999). EPBC Act 1999 (Commonwealth). Retrieved from https://www.environment.gov.au/system/files/resources/98c097c0-0325-4e3e-b203-685b84142ec2/files/epbc-act-policy-statements-reasons.docx

Fleishman, E., Blair, R. B., & Murphy, D. D. (2001). Empirical validation of a method for umbrella species selection. Ecological Applications, 11(5), 1489-1501.

Frank, B., Monaco, A., & Bath, A. J. (2015). Beyond standard wildlife management: A pathway to encompass human dimension findings in wild boar management. European Journal of Wildlife Research,61,723–730. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10344-015-0948-y

Frazier, J. (2005). Marine turtles: The role of flagship species in interactions between people and the sea. Mast, 3(2), 5–38.

Hammerschlag, N., & Gallagher, A. J. (2017). Extinction risk and conservation of the earth’s national animal symbols. BioScience, 67(8), 744-749.

Harris, J. M., & Goldingay, R. L. (2003). A community-based survey for the Koala Phascolarctos cinereus in the Lismore region of north-eastern New South Wales. Australian Mammalogy. 25(2), 155-167.

Jordan, R. C., Gray, S. A., Howe, D. V., Brooks, W. R., & Ehrenfeld, J. G. (2011). Knowledge gain and behavioral change in citizen-science programs. Conservation Biology, 25(6), 139-148.

Kelly, M. (1994). Life after gold: Twentieth Century Ballarat. Labour History, 67, 180- 181. doi:10.2307/27509296

Kelso, R. (2001). All creatures are equal, though some are more equal than others: The moral and political agency of Koalas. In K. Lyons, A. Melzer, F. Carrick & D. Lamb (Eds.) The research and management of non-urban Koala populations (pp..178-187). Rockhampton: Koala Research Centre of Central Queensland.

Lavrakus, P. J. (2008) Convenience sampling, In Encyclopedia of survey research methods. Sage. https://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781412963947.n105

Leader-Williams, N., & Dublin, H. (2000). Charismatic megafauna as ‘flagship species’. In Entwistle & N. Dunstone (Eds.), Priorities for the conservation of mammalian diversity: Has the Panda had its day? (pp.53–81). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Lunney, D., Esson, C., Moon, C., Ellis, M., & Matthews, A. (1997). A community-based survey of the Koala, Phascolarctos cinereus, in the Eden region of south-eastern New South Wales. Wildlife Research. 24(1), 111-128.

Marbach-Ad, G. (2004). Expectations and difficulties of first-year biology students. Journal of College Science Teaching, 33(5), 18-23.

Martin, R. W. & Handasyde, K. A. (1999). The Koala: Natural history, conservation and management. Sydney: University of New South Wales Press.

Menkhorst, P. (2008). Hunted, marooned, re-introduced, contracepted: A history of Koala management in Victoria. Too close for comfort: Contentious issues in human-wildlife encounters. Mosman: Royal Zoological Society of New South Wales.

Mills, L. (2012). Conservation of wildlife populations: Demography, genetics, and management (2nd ed). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell.

Moynes, E., Bhathe, V., Brennan, C., Ellis, S., Bennett, J., & Landsman, S. (2021). Flagship species: Do they help or hurt conservation? Fronters for Young Minds, 9, 576035. doi: 10.3389/frym.2021.576035

Phillips, S. S. (2000). Population trends and the Koala conservation debate. Conservation Biology, 14(3), 650-659.

Reinard, J. C. (2008). Introduction to communication research. 4th edition. Boston: McGraw-Hill Higher Education Incorporated.

Park, G., & Roberts, A. (2020). INFFER analysis: Koala conservation. Natural Decisions, Retrieved from https://www.awe.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/Koala-conservation-inffer-report.pdf

Rey Pérez, J., & González Martínez, P. (2018). Lights and shadows over the recommendation on the historic urban landscape: ‘Managing change’ in Ballarat and Cuenca through a radical approach focused on values and authenticity. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 24(1), 101-116.

Riessman, C. K. (2008). Narrative methods for the human sciences. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Roberge, J-M., & Angelstam, P. (2004). Usefulness of the umbrella species concept as a conservation tool. Conservation Biology, 18(1), 76-85.

Schlagloth, R., Santamaria, F., Golding, B., & Thomson, H. (2018). Why is it important to use flagship species in community education? The Koala as a case study, Animal Studies Journal, 7(1), 127-148. http://ro.uow.edu.au/asj/vol7/iss1/7.

Schlagloth, R., Callaghan, J., & Santamaria, F. (2004). Ballarat residents: Koala Survey 2002. City of Ballarat.

Schlagloth, R., Callaghan, J., & Thomson, H. (2006). Ballarat City Council: Comprehensive Koala plan of management, Part 2, [Resource Document]. Ballarat, Victoria: City of Ballarat.

Schussler, E. E., & Olzak, L. A. (2008). It’s not easy being green: Student recall of plant and animal images. Journal of Biological Education, 42(3), 112-119.

Seidman, I. (2013). Interviewing as qualitative research. A guide for researchers in education and the social sciences (4th ed). New York: Teachers College Press. Columbia University.

Siebuhr, L. (2000). Community education in the Koala coast. In Proceedings from the Conference on the Status of the Koala in 2000. (pp.155-162). Brisbane: Australian Koala Foundation.

Simberloff, D. (1998). Flagships, umbrellas, and keystones: Is single-species management passé in the landscape era? Biological Conservation. 83(3). 247-257.

Van Kerkoff, L., & Lebel, L. (2006). Linking knowledge and action for sustainable development. Annual Review of Environment and Resources 31, 445-477.

Veríssimo, D., Fraser, I., Bristol, R., Groombridge, J., & MacMillan, D. (2009). Birds as tourism flagship species: A case study on tropical islands. Animal Conservation, 12(6), 549-558. DOI: 10.1111/j.1469-1795.2009.00282.x

Wang F., Winkler J., Viña A., McShea, W. J., Li, S., Thomas, C., Zhao, Z., Wang, D., Yang,

H., Tang, Y., Zhang, J., & Liu, J. (2021). The hidden risk of using umbrella species as conservation surrogates: A spatio-temporal approach. Biological Conservation, 253, 108913. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2020.108913

Whisson, D. A., Dixon, V., Taylor, M. L., & Melzer, A. (2016). Failure to respond to food resource decline has catastrophic consequences for Koalas in a high-density population in southern Australia. PLoS One, 11(1), e0144348

Whisson, D., & Ashman, K. (2020). When an iconic native animal is overabundant: The Koala in southern Australia. Conservation Science and Practice 2(5), e188, https://doi.org/10.1111/csp2.188

Yang, Z., Gu, X., Nie, Y., Huang, F., Huang, Y., Dai, Q., … & Wei, F. (2018). Reintroduction of the giant panda into the wild: a good start suggests a bright future. Biological Conservation, 217, 181-186.

Rolf Schlagloth (PhD) (Corresponding Author) is a Central Queensland University lecturer with the School of Access Education and a researcher with the School of Health, Medical and Applied Sciences. He is committed to exploring the connections that people have with the flagship species, Koala. He has been working collaboratively on a series of journal articles on various aspects of koala conservation through his association with the Koala History and Sustainability Research Cluster and Koala Research-CQ.

Rolf Schlagloth (PhD) (Corresponding Author) is a Central Queensland University lecturer with the School of Access Education and a researcher with the School of Health, Medical and Applied Sciences. He is committed to exploring the connections that people have with the flagship species, Koala. He has been working collaboratively on a series of journal articles on various aspects of koala conservation through his association with the Koala History and Sustainability Research Cluster and Koala Research-CQ.  Honorary Professor Barry Golding AM is widely published in the international adult education field. His research has gravitated towards informal learning in community settings, with a specialization in older men’s learning and community Men’s Sheds: see www.barrygoanna.com.

Honorary Professor Barry Golding AM is widely published in the international adult education field. His research has gravitated towards informal learning in community settings, with a specialization in older men’s learning and community Men’s Sheds: see www.barrygoanna.com.  Barry Kentish (EdD) worked with Federation University and its predecessors, for almost three decades. His diverse research included aspects of freshwater ecology, bird pest management and latterly environmental ethics and the links to higher and community environmental education. The movement of his research towards a more philosophical basis is founded on his contention that it is essential for ethical considerations to underpin and inform environmental management decisions.

Barry Kentish (EdD) worked with Federation University and its predecessors, for almost three decades. His diverse research included aspects of freshwater ecology, bird pest management and latterly environmental ethics and the links to higher and community environmental education. The movement of his research towards a more philosophical basis is founded on his contention that it is essential for ethical considerations to underpin and inform environmental management decisions.  Gabrielle McGinnis is a PhD graduate from the University of Newcastle, with research interests in Indigenous methodologies, biocultural heritage conservation and sustainable tourism development using digital technologies. Gabrielle is CEO and Founder of BrodiMapi LLC, whose mission is to provide digital mapping and marketing services to those who wish to preserve, conserve and share biocultural heritage. She is currently focusing on koala tourism and its history as a researcher, digital media manager and is a co-founding member of the Koala History and Sustainability Research Cluster.

Gabrielle McGinnis is a PhD graduate from the University of Newcastle, with research interests in Indigenous methodologies, biocultural heritage conservation and sustainable tourism development using digital technologies. Gabrielle is CEO and Founder of BrodiMapi LLC, whose mission is to provide digital mapping and marketing services to those who wish to preserve, conserve and share biocultural heritage. She is currently focusing on koala tourism and its history as a researcher, digital media manager and is a co-founding member of the Koala History and Sustainability Research Cluster.  Ian D. Clark is an Adjunct Professor at Federation University and Monash University. He holds a PhD from Monash University in Aboriginal historical geography and has been researching Victorian Aboriginal and settler colonial history since 1982. His research interests include biography, local history, toponyms, the history of tourism, and genealogy. He is a co-founding member of the Koala History and Sustainability Research Cluster, a collaboration of researchers from different disciplines concerned with the future of the iconic koala.

Ian D. Clark is an Adjunct Professor at Federation University and Monash University. He holds a PhD from Monash University in Aboriginal historical geography and has been researching Victorian Aboriginal and settler colonial history since 1982. His research interests include biography, local history, toponyms, the history of tourism, and genealogy. He is a co-founding member of the Koala History and Sustainability Research Cluster, a collaboration of researchers from different disciplines concerned with the future of the iconic koala.  Tim Cadman is a Research Fellow in the Institute for Ethics, Governance and Law and the Law Futures Centre at Griffith University. Tim specialises in the governance of sustainable development, natural resource management including forestry, and climate change. He is currently overseeing the implementation of a research project in Nepal focused on the protection of the red panda through habitat conservation and restoration at the landscape level, in collaboration with local communities.

Tim Cadman is a Research Fellow in the Institute for Ethics, Governance and Law and the Law Futures Centre at Griffith University. Tim specialises in the governance of sustainable development, natural resource management including forestry, and climate change. He is currently overseeing the implementation of a research project in Nepal focused on the protection of the red panda through habitat conservation and restoration at the landscape level, in collaboration with local communities.  Fred Cahir (PhD) lives and works on Wadawurrung Country at Ballarat, Victoria. He is Associate Professor of Aboriginal History in the School of Arts at Federation University Australia. His research in recent decades has been focused on Victorian Aboriginal history during the colonial period, and on understanding the contribution Aboriginal people made to the foundations of our nation-state, and of the roles they played on the frontier, especially in connection to fire, flood and food.

Fred Cahir (PhD) lives and works on Wadawurrung Country at Ballarat, Victoria. He is Associate Professor of Aboriginal History in the School of Arts at Federation University Australia. His research in recent decades has been focused on Victorian Aboriginal history during the colonial period, and on understanding the contribution Aboriginal people made to the foundations of our nation-state, and of the roles they played on the frontier, especially in connection to fire, flood and food.  Flavia Santamaria’s PhD researched the impact of translocation on the health, food selection and movement of koalas from French Island to forests around Ballarat, Victoria. Flavia has worked on projects that included GIS koala habitat mapping and koala surveys in Victoria and Queensland. Her current and future research foci are on koalas' response to stress and koala ecology, and in particular the impact of anthropogenic environmental changes on koala populations, including the potential pressure of environmental stress on their health (i.e., Chlamydia). She is committed to educating communities on sustainability using the koala as a flagship species.

Flavia Santamaria’s PhD researched the impact of translocation on the health, food selection and movement of koalas from French Island to forests around Ballarat, Victoria. Flavia has worked on projects that included GIS koala habitat mapping and koala surveys in Victoria and Queensland. Her current and future research foci are on koalas' response to stress and koala ecology, and in particular the impact of anthropogenic environmental changes on koala populations, including the potential pressure of environmental stress on their health (i.e., Chlamydia). She is committed to educating communities on sustainability using the koala as a flagship species.