Cultivating Change: A Cross-Age Arts, Literacy, and Sustainability Project

Table of Contents: February 2018 — Arts, Social Change, and a Vision for Sustainability

Kinkead JSE Feb 2018 Cultivating Change Arts Issue PDF

Introduction

This essay describes a cross-age project between a fourth grade class and university students in which the two groups of students worked together on a dramatic performance of Paul Fleischman’s Seedfolks (1997, 2014). Cross-age projects tend to focus on tutoring, particularly in reading skills with more advanced students helping younger students (e.g., Labbo and Teale; O’Bryne; Pavona). In contrast, this project enriched arts and literacy practices for students of both groups while also introducing themes of sustainability. By sustainability, we mean working with current resources to ensure they are not depleted for future generations. We wanted our students to understand the potential impact of sustainability and how changing behaviors could help improve our world. The results also surprised us when the students initiated a pen pal correspondence.

The Partners

Alice Waters (2008), famed chef of Berkeley’s Chez Panisse, has been an advocate of school gardens so that children experience the thrill and pride of growing their own food and learn about healthy eating. Hillcrest Elementary School created a school garden in 2015 in order to provide students with opportunities for hands-on learning while connecting to nature and learning about how food grows. By covering the four pillars of sustainable facilities, sustainable practices, community involvement, and environmental curriculum, the garden helped Hillcrest achieve a Green Schools platinum award through the Utah Society for Environmental Education.

This history of prioritizing sustainability and community involvement made Hillcrest a particularly suitable partner for a project on sustainability. The fourth grade class that participated in this project consisted of 24 students–14 boys and 10 girls. Six of the students qualified for English as a Second Language.

The Utah State University Honors Program initiated in spring 2016 a special Think Tank curriculum focused on sustainability. One of the three classes looked at sustainability through an arts and humanities lens. A dozen students enrolled, none of them majoring in arts nor humanities. Over the course of the semester, the university students curated an exhibition at the campus art museum that focused on “Growing West: Art, Agriculture, and the Land” and also created digital exhibits on sustainability themes of food waste, alternative markets, urban farms, and food sheds. (See Honors Students 2016 and Sand et al 2017.) When the teacher of the course sought out an elementary school class as collaborators, Hillcrest, with its history of commitment to sustainability and its school garden project, was a natural.

Literary Selection

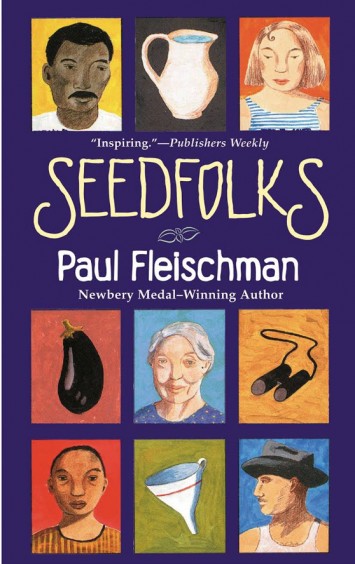

Resources for children’s literature that focus on farm-to-school exist among several organizations. One of the best is Growing Minds, with its list of over 500 books. Among the titles is Seedfolks, the story of how one child planted some seeds in a vacant lot in a city and managed to transform a community. We particularly liked this novel for its depiction of a diverse group of people who find common cause in an urban garden. Paul Fleischman penned the novel in 1997, and it has been read widely, often adopted as a community book. He followed it with a dramatic version that is available through Playscripts. It can be produced in 40 minutes and features an expandable and contractible cast: 15 females and 15 males with 10 either gender, or as many as 75 actors possible. Fleischman considers it a “spoken musical,” although musical talent is not required.

Kim, the young Vietnamese girl who plants the first seeds in the trashy lot, does so to connect to the memory of her father. She is seen by the elderly Ana from her apartment window, who then contacts Wendell, a school janitor, to help the girl keep the plants watered. Wendell, who grew up on a farm in Kentucky—and is most likely a reference to noted writer, farmer, and environmentalist Wendell Berry—finds his own patch of soil amid the rubble and plants some seeds. Gradually, others come: Curtis, who wants to impress his girlfriend Lateesha, who loves tomato sandwiches; Philippe, the taxi driver, who thinks that by growing baby lettuces to sell to restaurants, he can save funds for his daughter Ginny’s college tuition; Gonzalo’s Uncle Juan, who has been a lost soul since emigrating from Guatemala until he discovers the garden.

A fourth grade teacher in the play, Leona, cleverly finds a way to get the city to clean up the lot. (Yes, we love books that feature teachers as heroes!) The rats and stray cats of Scene One make way for carefully tended plots. Characters begin to know others as individuals rather than as stereotypes such as the Korean woman who runs the dry cleaning store or the Indian man who has a bakery. They become Sae Young and Amir, friends who share their cornucopia in a final ensemble barbecue celebration.

The Process

The university students prepared for the Seedfolks experience by watching the moving documentary, The Garden (2008), which tells the story of a real vacant lot that is colonized by multiethnic gardeners. As in Seedfolks, a vibrant community forms; however, the garden is in peril due to an owner who wishes to develop it. In spite of legal skirmishes, the owner succeeds in having the garden plots bulldozed. Ironically, it returned to being a vacant lot with no development. Seedfolks ends more happily and more appropriately for a younger audience.

Overall, the process for both classes took about a month. In the university classroom, the novel Seedfolks was read first. Then, these students read the script cold during class, choosing roles by luck of the draw in gender-blind, color-blind casting. Limited to a one-day visit to the elementary school, the children would act out the play while the college students read the parts. We were influenced, in part, by a YouTube video in which a high school drama class produces a shadow play that is presented to younger students preparing to read the book. (See https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qpNy33w_ViU). Additionally, the children were invited to claim props for staging the play so they were invested in its production.

With a plan in mind on how to produce a 40-minute play in the constraints of one day, the two teachers collaborated on presenting the facts of the production to the younger group. We shared the novel versions of Seedfolks and asked if any had read it. None had, but several asked to take it home to do so. (It is an accessible book for almost any age, which has made it a popular entry in the One Book program in which entire communities read the same title.) Then, we handed out the script versions and asked the children to find the differences. Scene One, which introduces the ensemble of actors in the vacant lot, was read, and the teacher noted how the italicized parts offered stage directions.

We explained the approach to our production with the college students reading and the children acting. We practiced acting out the part of Kim while the script was read. It became clear that the words—Kim digs holes with a spoon and puts in two bean seeds—provided information for the child actor. We practiced Ana’s role using a cane to demonstrate how an elderly person might walk. While costumes were not required, a detail such as a straw hat might help to illuminate a character. We also performed sound effects such as the rats and howling cats that appear in the first scenes. In short, we had a lot of fun while also learning about how plays are read and staged.

The fourth-grade teacher helped students select parts and familiarize themselves with the play, entrances, and sound effects. All of the roles were projected on the smart board, and students selected the parts they wanted to perform. Each student received a copy of the script and followed as the teacher read the play aloud. The students noticed various ways that the script was similar to and different from a novel: stage directions, names listed before speaking parts, props. As the teacher read the play, the students practiced acting out their parts and also brainstormed additional props they could bring.

The teachers developed an introduction and welcome to contextualize the play for the audience members—parents and school staff. The two sets of students had a quick meeting to discuss scenes in advance, and then the play began. The fourth grade teacher functioned as stage manager, helping students with their cues. With five minutes to spare before bus departure, the play came to a successful close with the actors bringing in a cornucopia of fruits and vegetables, once again gathering as an ensemble to celebrate the garden that has brought them together.

Sustainability Themes

The university students wrote reflections about the Seedfolks experience, which were discussed in class, while the elementary school students discussed the production in class and then wrote letters to the college students. As teachers, naturally, we were interested in their analysis of this theatre production in terms of the meaning of the play. Although the students varied in age by a decade or more, all of them saw similar themes from their reading and the production of the script.

- The power of a child to change a community.

- The importance of producing one’s own food.

- The fact that stereotypes dissipate when people become friends.

- Activism can improve a community.

- Gardening and food production make people feel valued.

- Pride in a community comes from working together.

These are exactly the messages we hope that students will take away from a powerful narrative such as Seedfolks that demonstrates beautifully how one person can have a significant influence on community in a positive way.

Cultivating—Literally and Poetically

While the fourth graders were preparing for Seedfolks, they planted pumpkin seeds in the school garden and sunflower seeds in cups, which they took home. Our classes were focused on Seedfolks as literature, but the science teacher used the experience to reinforce lessons in plant science, climate science, and horticulture. This cross-disciplinary approach, drawing on literature and STEM skills can be a powerful learning tool as it demonstrates the interconnectedness of learning. After the performance, the fourth graders showed heightened interest in the school garden, asking for time to water, weed, and check on the plants. The university students, likewise, felt heightened interest in local food, farmers’ market, and community gardens.

As a complementary literature extension, the 4th grade students listened to and reflected on Robert Frost’s “Putting in the Seed,” which is featured in the American Academy of Poets’ “Teach This Poem” initiative and is in the public domain.

Putting in the Seed

You come to fetch me from my work to-night

When supper’s on the table, and we’ll see

If I can leave off burying the white

Soft petals fallen from the apple tree.

(Soft petals, yes, but not so barren quite,

Mingled with these, smooth bean and wrinkled pea;)

And go along with you ere you lose sight

Of what you came for and become like me,

Slave to a springtime passion for the earth.

How Love burns through the Putting in the Seed

On through the watching for that early birth

When, just as the soil tarnishes with weed,

The sturdy seedling with arched body comes

Shouldering its way and shedding the earth crumbs.

–Robert Frost

The fourth grade students connected this poem to their personal planting experience of “putting in the seed” and watching their plants grow (or not):

I had fun planting seeds of sunflower. I kept it at home, gave it water and took its care. It hasn’t grown up yet but I hope it’s gonna be big when I give it lots water and take more care of it.

When I planted the seed, I felt more active and responsible for at least two weeks. It died because one week I totally forgot to water it. So there you have it, my experience of growing a plant. P.S. I loved planting a seed.

My plant is growing and I water it every day I am so glad that my plant is growing and I put it really high so when little kid can’t reach it so it can grow, and so my plant can grow well

Both teachers were pleased at the students’ increased interest in sustainability, food, and community through this arts collaboration. The college students were viewed as accessible and friendly; they invited the younger students to the campus art museum to see the exhibition they curated, “Growing West: Exploring Art and Agriculture,” and also gave them packets of wildflower seeds that they had designed to market the show.

The students surprised us with a pen-pal initiative. When the two groups met, the college students were taken aback that the fourth graders did not necessarily envision themselves as future college students. “We’ve got to do something about that,” they said in a follow-up class meeting. But what? They suggested that they write to the younger students and develop a pen-pal relationship. The older students began by explaining what it means to be a college student and recommending higher education. As the correspondence continued, the college students wrote the fourth graders a thank you card and sent them a book for Poem in Your Pocket Day. This unique book from the Academy of American Poets invites readers to rip out a poem and carry it in their pockets. Celebrated annually in April, Poem in Your Pocket Day began in 2002. (See https://www.poets.org/national-poetry-month/poem-your-pocket-day.) On April 21, the fourth graders each proudly selected a poem from the book that they recited to their classmates as part of their morning greeting. Then, the fourth graders penned letters to their counterparts. Many of the fourth graders included the role they played when signing their names, suggesting the meaningfulness of the experience. The teacher has provided a description of the student in brackets following each letter. [Pseudonyms are used for the students to protect their identities.]

Dear College Students,

Thank you for coming to the hillcrest elementary school and together with our complete drama, of course, show was very successful. In conclusion, I think you are pretty good!

[From a 4th grader, who moved to the U.S. from China 3 months before participating in the play]

Dear College Students,

I had fun performing Seedfolks. It was pretty hard. I hope you enjoyed it to. You guys should have told us that Sam was a girl because my friend (That’s a boy.) didn’t know either. P.S. At college, do they teach you how to be a mechanic there because I want to be one.

From: Gonzalo and Robber

[From a student who was born in Mexico and plans to be the first person in his family to go to college]

Dear College Students,

What’s it like in college and thank you for doing the play with us it was realy nice to meet you how long did it take you to get everything down. I hope you can come back again.

part rat.

[From a student, who a month before Seedfolks, had declared that he would not be going to college because “that’s not something people in [his] family do.”]

To all the college students and their teacher

Special thanks to all of the college students who came to the Seedfolks play. I was glad to see you there. You were not only reading the parts but you were like our audience.

Special thanks to the teacher of the college students who were very kind and gentle.

Thanks!

Role: Sae Young

[From a student who moved to the U.S. from Pakistan, 4 months prior to Seedfolks.)

The college students wrote back with information about college, encouragement and advice. Here is one such response.

I’m going to share some advice that I hope will stick with you for a while: If you work hard and want something badly enough, then you will find a way to make it work. “Luck” is a funny word–sometimes, you do get lucky in life. But don’t blur “luck” with your accomplishments. Be yourself, recognize your talents, and never settle. You can do a lot of amazing things if you put your mind to it! [Liz]

Royalties and Staging Fees: The Nuts and Bolts of Drama Production

An important lesson on copyright can be taught by discussing the royalties and license fees. Script copies as of this writing cost about $9 each with a stage manager’s binder version at $18. To perform the play, a license fee of $50 is required. We ordered 25 copies, which were shared among students, abiding by the copyright laws not to use photocopies. Another legal requirement is that the play is to be performed without cuts with the exception of the scene with a pregnant teen, which may be deleted for grades below five. We took that option.

The script calls this a “spoken musical,” and it also provides suggestions for music, such as a banjo playing in connection with Wendell, the Kentucky farmer turned school janitor. To prepare, we developed a list of characters and props scene-by-scene. This was tremendously useful in our production.

Reflections

The students reflected on the experience. Rather surprisingly, each group—yes, even the college students–was rather tentative and fearful about the collaboration.

From the college student perspective:

The theme of Seedfolks was to build something together. I don’t think it would have worked as well if our class did it by ourselves. A college class putting on the play would have felt more like just an assignment and not actually living out the script. Because we worked with the fourth graders, it was more of a real life situation about coming together. It worked since we had cross-age roles with the fourth graders acting, the college students voicing the roles, and the teachers helping guide and direct the on-stage performance. It really felt like we were coming together as a cast, which was parallel to the theme of the production. It was perfect. [Mason]

Seedfolks, a story about a single girl who made all the difference, managed to give our two groups a chance to come together and reach a better understanding, even if it was only through performing together for forty minutes. [Shelby]

From the fourth grade Perspective:

I think the Seedfolks play was really fun and it was the first play I had done. I was Kim and a female admirer. I was also a sister. Thanks to this play I have a new best friend named Shandrea [college student]! I hope we can do a play again.

I enjoyed being able to act again, and put myself in someone elses shoes and being able to feel how someone else feels even if I didn’t speak!

I felt kind of shy when I preformed Seedfolks. It was hard to me but at least we did it. P.S. by mechanic I mant a car fixer. I loved performing. (Well I guess.)

When I was at the play I learned and expernsed that it is rilly hard. It was fun though. It was hard picking a few parts and also fun acting. It was fun meeting the USU students.

Overall, we wanted to cultivate change on many levels. The teachers’ goals included having the students learn cooperatively from one another, crossing boundaries of age. We envision that this project could be undertaken by other cross-age groups. Most importantly, the Seedfolks project was viewed by all students as meaningful and authentic. The artistic content and production supported and reinforced sustainable behaviors in positive ways. We are also hopeful that the university students inspired their younger counterparts to sustain their own educational pathways and eventually pursue a college education. Our objective was to enact profound learning, making connections through instruction and community building. If we are successful in bringing together these two groups—a fourth grade multiethnic classroom and college undergraduates—in a meaningful connected learning experience, then our students will be citizens who have the potential to influence, change, and give back to their own neighborhoods and communities.

References

American Academy of Poets. Poem in Your Pocket Day. Retrieved from https://www.poets.org/national-poetry-month/poem-your-pocket-day.

American Academy of Poets. “Teach This Poem: ‘Putting in the Seed’ by Robert Frost.” Retrieved from https://www.poets.org/poetsorg/lesson/teach-poem-putting-seed-robert-frost.

Fleischman, P. Author website. Retrieved from http://www.paulfleischman.net/newsletter.htm.

Fleischmann, P. (1997). Seedfolks. NY: HarperCollins.

Fleischmann, P. (2014). Seedfolks. NY: Playscripts.

The Garden. (2008) Scott Hamilton Kennedy, Director.

Growing Minds Farm to School. Children’s literature. Retrieved from http://growing-minds.org/.

Honors students curate exhibit “Growing West: Exploring Art & Agriculture.” (2016) Utah State Today, Retrieved from https://www.usu.edu/today/?id=55578.

Labbo, L., & Teale, W. (1990). Cross-age reading: A strategy for helping poor readers. The Reading Teacher, 51, 122-127.

O’Byrne, B. (2003). The Paradox of cross-age, multicultural collaboration. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy 47(1), 50-63. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40026904.

Pavona, H. (2010). Grade 9: Cross-Age Literacy. Go To Service Learning. Retrieved from http://www.ceesa.org/phocadownload/servicelearning/part_3_organizations_resources/16_GlobalYouthService/6_GoToServiceLearningLessonPlans/8_grade9_cross-ageliteracy.pdf

Sand, A., Thoms, B., Davis, E., Pumphrey, D, & Kinkead, J. (2017). Curating exhibitions as undergraduate research. CUR Quarterly 37(4), 12-17.

Utah Society for Environmental Education. Retrieved from http://www.usee.org/programs/utahgreenschools.

Waters, A. (2008). Edible Schoolyard: A Universal Idea. San Francisco: Chronicle Books.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the generosity and support of the Utah State University Honors Program, directed by Dr. Kristine Miller, which funded the Seedfolks production.

Joyce Kinkead is Professor of English at Utah State University, the 2013 Carnegie Foundation U.S. Professor of the Year for Utah, and a Council on Undergraduate Research (CUR) Fellow. She uses Farm: A Multimodal Reader by Kinkead, Funda, and O'Neill to teach a course on the Farm in Literature and Culture.

Joyce Kinkead is Professor of English at Utah State University, the 2013 Carnegie Foundation U.S. Professor of the Year for Utah, and a Council on Undergraduate Research (CUR) Fellow. She uses Farm: A Multimodal Reader by Kinkead, Funda, and O'Neill to teach a course on the Farm in Literature and Culture.  Andrea Melnick taught fourth grade at Hillcrest Elementary School in Logan, Utah during this project but has since moved to teaching kindergarten.

Andrea Melnick taught fourth grade at Hillcrest Elementary School in Logan, Utah during this project but has since moved to teaching kindergarten.  Olivia Webb served as the Undergraduate Teaching Fellow for the university course described in this essay and will graduate USU with Honors.

Olivia Webb served as the Undergraduate Teaching Fellow for the university course described in this essay and will graduate USU with Honors.