Collaborative Ground Work in an Urban Green School: Empowering Students as Change Agents

Link to the JSE General Issue May 2022 Table of Contents

Jennings et al JSE May 2022 General Issue PDF

Abstract: This case study provides insights into a collaborative effort involving D.C. Virgo Preparatory Academy, a public university-run lab school in downtown Wilmington, North Carolina. The article overviews the combined efforts of DCVPA staff, university faculty, and community partners to engage the students in unique, hands-on learning experiences, particularly in the STEM areas. Students have taken the initiative to serve as change agents and leaders in the work. Several efforts at the school, including a composting program, a recycling effort, a seedling project, and a mycology lab, provide a window into dynamic experiential learning that has brought the university and school together.

Keywords: Sustainability education, Teacher leadership, Student agency and leadership, Green School

Introduction

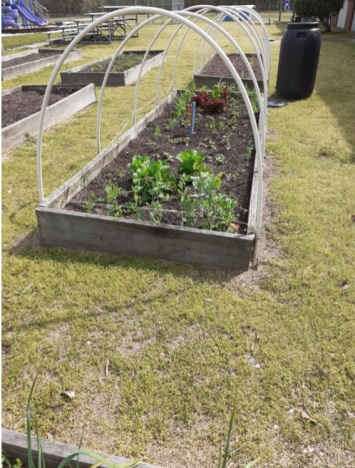

As the sixth-grade students gathered around the large planter boxes, the raised garden beds provided both an artist’s palette and a classroom laboratory for students to learn about how composted food waste could be converted to plant-based nutrition. A university doctoral student shared tips on the gardening project with a small group of middle schoolers, noting how wheat straw could be used to grow oyster mushrooms in a composting effort. Kensler and Uline (2017) describe the importance of place in the identity development of children and that agents such as teachers, parents, and volunteers can be leveraged to help students begin to see themselves as change agents and stewards of the environment.

A learning garden project in downtown Wilmington, NC, allows students to be a part of a hands-on transformation project. Louv (2012) describes how a school learning garden can empower students to learn about their own backyard and then to go “beyond their garden” (p. 208) and study local and regional areas around them, and take advantage of nearby nature as “an integral element” (p. 212) in improving both physical and mental health. In this work, Louv advocates for “natural teachers” who are not necessarily environmental educators but are “the teachers who intuitively or experientially understand the role that nature experience can play in education” (p. 262). These “natural teachers” that introduce formerly abstract concepts into real-world experiences can turn a learning garden into a larger opportunity to understand the sciences, engage in collaborative learning, and help tell the story of their place and identity in the world.

D.C. Virgo Preparatory Academy is a public lab school located in the Northside area of Wilmington, North Carolina, serving over 200 students in a K-8 setting, including 94% minority and 99% who qualify for free or reduced lunch. The school is a university-run lab school that was formerly a traditional public middle school. Due to state legislation, the University of North Carolina Wilmington partnered with New Hanover County Schools to transform the 6-8 middle school into a K-8 partnership lab school in 2018 (D.C. Virgo Preparatory Academy, 2022). Part of its founding mission was to provide unique, hands-on learning experiences, particularly in the STEM areas. University faculty, school teachers and administrators, and a cadre of volunteers have worked together to help provide students the opportunities to see themselves as lifelong STEM learners and leaders. Several efforts at the school, including a composting program, a recycling effort, a seedling project, and a mycology lab, provide a window into dynamic experiential learning that has brought the university and school together. These projects have allowed the school to partner with the Coastal Composting Council, UNCW Recycling, UNCW Sustainability, and the New Hanover County Arboretum and students to problem solve and learn in real-world contexts.

Collaborative Learning and Leading

Student agency in recycling and repurposing in the elementary grades

Battro, Lena, Sorondo, and von Braun (2017) note that “children are exposed to current and future social, economic and environmental sustainability problems, but are also potential agents of change for sustainability, even in childhood” (p. 17). One fifth-grade student at DCVPA is representative of being a change agent. This student recognized a need for our school to be more active in addressing environmental issues on our campus. New initiatives brought upon by the COVID pandemic have forced many schools to be creative in meeting their students’ basic needs, particularly with something as simple as drinking water. Our school met this need by providing all of our students with bottled water throughout the day. Our change agent noticed that students were throwing their bottles away, and she thought we could be doing something more environmentally friendly by recycling or repurposing them. This motivated her to share her idea with her teacher and classmates, and soon after, our recycling program began.

With the direction of our change agent, the fifth-grade class came together and developed a plan for our recycling program. They researched appropriate and inappropriate items to recycle and created a school-wide presentation. The students presented in each classroom and shared their research about environmental concerns in our school and community. They provided students with visual support to help them identify the right items to recycle. With the support of their teacher, the students were able to connect with the University of North Carolina at Wilmington and partner with the UNCW Sustainability Program to learn more about the recycling process and arrange for recycling stations to be set up on our campus (see Photograph 1). Each week our fifth graders weigh and collect the recycling from each class. Our school-wide weekly morning meeting recognizes the class that collects the most recycled items. All of our recycled products are then picked up by UNCW and transported to a recycling center located on the university campus. We have also found a way to repurpose the water bottles in our gardening program. Water bottles are used to start seedlings, create watering cans, and are used as planting containers (see Photograph 2).

Since implementing our recycling program, we have noticed increased student awareness and involvement in support of this program. Students hold each other accountable and educate those who are not properly disposing of their water bottles. Students become stakeholders in their learning community and take the extra effort to model actions representative of an environmentally friendly community. In March, in collaboration with the UNCW Sustainability program, the students hosted an electronics drop-off recycling event for the school and the surrounding community.

The assistant principal works with the fourth-grade teacher and students to introduce “biodegradable and nonbiodegradable” concepts. This has led to taking action on planning for integrating campus compost bins and a worm farm at the school. Dr. Jennings supported the initiation of the purchase of three compost bins with three more on the way and led the students in building a worm farm bin to explore soil nutrition through vermiculture. Students created a supply list of materials for the worm farm, such as 31-gallon tubs, and in smaller groups engaged in supervised components such as 1.) drilling holes in the tubs; 2.) shredding paper for the tubs; 3.) collecting organic matter such as leaves and sticks. As students rotated through the stations, staff and students constructed the worm farm (see Photograph 2). Each fourth-grade student input the shredded paper, organic matter, was given a worm to welcome to its new home, and completed their worm farm, adding food scraps as compost.

Students created posters indicating what could go into the compost bins, and the worm farm developed presentations about the importance of composting and vermiculture and discussed ways their peers could help support the program. The student teams then shared what they learned to all K-8 classes, teaching concepts such as soil nutrients for our garden beds, how our food scraps can help the vegetables we grow, and the guidelines for feeding the worms.

Growing seeds and ideas in the middle grades

The assistant principal then taught the concept of seed germination with fruits such as avocados, mangos, and lemons. She took the lemon seeds, for example, in window sills of the school and then transferred them into a mini-greenhouse in the fall. She also taught the students how to regrow vegetables using vegetable scraps, such as celery, carrots, parsnips, green onions, and Bok choy. As the plants have grown, they are transferred into larger pots. Meanwhile, the school benefited from a local community partnership that supplied the school with seeds. The UNCW Sustainability program supplied kits with seed packets, soil, containers, and instructions for planting to support students receiving instruction virtually. This allowed the hands-on learning to continue in the pandemic and focus on growing vegetable seeds such as jalapenos, tomatoes, red kale, and cucumbers (see Photograph 3). This Virtual Gardening allowed students who were completely online to engage in the seed planting concepts while learning at home.

Outdoor learning environments provide experiences and teachable opportunities which cannot take place in the confines of the traditional classroom setting. The DCVPA outdoor learning initiative enhanced the learning environment, not only from a pedagogical framework but also in an andragogic context. A doctoral student, Sohail Sukhera, was introduced to Ms. Kemeka Sidbury’s sixth-grade class through the school-university partnership. Learning about mycology was an opportunity for Ms. Sidbury to gain new insights aligned with relevant strands of the sixth-grade curriculum. Sidbury realized that instead of learning a new concept through professional development or an online search, she was able to learn alongside her students by engaging with Sukhera in hands-on science applications. The freedom to choose environmental education activities and to tailor them to teaching teams would benefit school and community partnerships (Mosley, Reinke, & Bookout, 2002). For example, the culture work aspect of mycology introduces students to the petri dish work aspect of microbiology. Sukhera works on a weekly basis with the two 6th grade science classes.

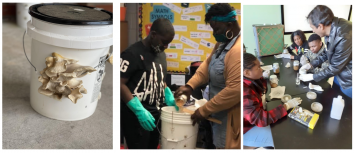

On “Mycology Fridays,” students learn to transfer oyster mushrooms’ mycelium culture from one petri dish to the next in front of a laminar flow hood which the students have put together with readily available supplies. Once the mycelium culture has grown on the new Petri dishes, it is transferred to sterilized grain in front of the laminar flow hood. The myceliated grain is then transferred to cold pasteurized wheat straw or sawdust. Observing the mushrooms growing from the wheat straw buckets brought both joy and a sense of academic achievement in the middle grades learning environment, as students have seen almost the entire life cycle of mushroom growing (see Photograph 4).

And through the midst of a pandemic “pivot,” the mycology work has been done by students attending class in person and shared with those attending classes remotely via video conference call. Technology has allowed Sukhera to join remotely, while Ms. Sidbury works with the students attending class in person and shares the hands-on work with those attending the class remotely. As the students who have observed mycology work remotely come to attend school in person, they are given the opportunity to have the same hands-on experience as well. Vassiliev, Gardner, and Neivandt (2020) indicated when STEM teachers are able to draw from research experiences and hold them up as a model as they discuss the nature of science, students are encouraged to persevere and tackle significant long-term endeavors.

The success with mycology in sixth grade led to an opportunity to learn about grafting tomatoes in eighth grade. Through the school-university partnership, the staff procured the necessary supplies to provide students with hands-on opportunities to grow rootstock tomatoes and graft with heirloom varieties. Preparations are underway for students to be introduced to controlling pest and soil-borne diseases using grafting techniques. In our preparatory stage, the students have been introduced to these agricultural techniques to grow sustainably and organically. Students will gain insights on cultivating seeds, engaging in grafting techniques, and then growing these grafted tomato plants in the raised beds.

Cultivating community partnerships on school grounds

Learning concepts such as composting and gardening has led to renewed interest in repairing and rebuilding dormant raised garden beds at the school. Middle-grade students have taken on leadership roles in learning and then lead in planting, weeding, and watering raised beds. Sukhera and Sidbury began by introducing students to locally grown vegetables ranging from tomatoes and cucumbers to sweet potatoes and watermelons. Sukhera emphasized the safety and use of gardening tools, including spades, rakes, hoes, hammers, and drills (for repairing the fixed beds- Photograph 5). Students maintain this work, and the school has fostered community involvement for ongoing improvements. A local master gardener has regularly volunteered to teach students to grow vegetables in the raised beds. She has introduced students to measuring rainfall, gauging the distance between rows and between each plant, checking for moisture content, and observing ladybugs and butterflies.

The university sustainability office has been helping with the gardening project, sharing several presentations to introduce DC Virgo students to sustainable ecological practices. At a “Green Future” presentation, topics included composting, rain run-off, solar power, and recycling efforts. And in collaboration with the university’s Randall Library and Center for Education in STEM (CESTEM), the school is piloting a program for the use of a FarmBot garden. FarmBot is a robotic farm machine that automates the seeding, tending, watering, and weeding of a garden through a computerized system that the students can program. This high-tech garden can monitor almost every aspect of plants while students control it like an interactive application or game. A robot arm plants vegetables, waters them, monitors soil conditions, and captures images. The students will control all of the tools from a web app with a “virtual garden that functions as if a simulator video game had a real-life companion” (FarmBot, 2021).

Final Reflections

The collaborative work of the school, university, and partnerships was affirmed while emerging from the COVID 19-impacted school year. In April 2021, the school received notification of being designated as a U.S. Department of Education Green Ribbon School (ED-GRS) for demonstrating combined progress in the following three areas:

1.) reducing environmental impact and costs;

2.) improving the health and wellness of schools, students; and

3.) providing effective environmental and sustainability education (U.S. Department of Education, 2021).

This work leading up to this recognition provided the opportunity to reflect on the engagement of the learning community in all three areas and to be mindful of how we define our success as a K-8 collaborative lab school. Student and staff voices attest to the powerful potential of this sustainability work. Assistant principal, Dr. Laura Jennings, details the gardening enrichment program and how students learn about the “seed to plant, and garden to table processes” in this video (https://vimeo.com/664923488). Students shared insights about learning about a rosemary bush and how plants attract insects. A master gardener and volunteer described how the “garden is an ideal place to learn.” Student ownership and agency through these green school projects have empowered students as change agents and problem solvers.

The school-university partnership work was made possible by having an established support team where school and university staff met weekly to discuss ideas and opportunities, including how to engage partners, ways to involve university and volunteers on a regular basis, and share ideas regarding grants or curricular opportunities. Green school efforts provide a shared learning space for stakeholders to share time, expertise, and a commitment to student learning. Supporting this work with time and space for collaboration is essential for schools looking to replicate this work.

Amid a historic pandemic, school and university faculty and staff have worked to empower students as change agents at D.C. Virgo. From cultivating seedlings to sharing voice and agency in the stewardship of resources, green learning has brought the learning community together. Even in a time of social distancing, a collaborative ethos has been nurtured, and former “silos” of innovation have been linked through the shared goal of fostering student agency in sustainability efforts. The groundwork has been sown, the seeds have been planted, and the learning community will reap the harvest. This work has been further strengthened by engaging community partners who share a mutual interest in valuing the important role that nature plays in the teaching, learning, and development of children.

References

Battro, Lena, Sorondo, & von Braun (2017). Children and sustainable development: Ecological education in a globalized world. Springer International Publishing.

D.C. Virgo Preparatory Academy (2022). Home page. Available: https://uncw.edu/virgo/

D.C. Virgo Green Ribbon School (2022). Gardening. Available: https://vimeo.com/664923488

FarmBot (2021). FarmBot overview. Available: https://farm.bot/

Kensler, L. A. W. & Uline, C. L. (2017). Leadership for green schools: Sustainability for our children, our communities, and our planet. Routledge.

Louv, R. (2012). The nature principle: Reconnecting with life in a virtual age. Algonquin Books.

Moseley, C., Reinke, K. & Bookout, V. (2002). The effect of teaching outdoor environmental education on pre-service teachers’ attitudes toward self-efficacy and outcome expectancy. The Journal of Environmental Education 34(1), 9-15.

U.S. Department of Education (2021). Green ribbon schools. Available: https://www2.ed.gov/programs/green-ribbon-schools/index.html

Vassiliev, T., Gardner, D. J., & Neivandt, D. (2020). How STEM teachers can immerse themselves in the Three Rs over the summer. Science Scope, 43(7), 8-11.

Laura Jennings, Ed.D. serves as the assistant principal and the Exceptional Children's director at D. C. Virgo Preparatory Academy. Her interests include home and community gardening and providing children with opportunities for learning with nature as the classroom.

Laura Jennings, Ed.D. serves as the assistant principal and the Exceptional Children's director at D. C. Virgo Preparatory Academy. Her interests include home and community gardening and providing children with opportunities for learning with nature as the classroom.  Kemeka Sidbury serves as a sixth grade middle school math and science teacher, and she is also advancing her role as educational leader through the University of North Carolina at Wilmington MSA add-on licensure program. As an educational leader, her interests include content integration, school-community partnerships, and culturally relevant pedagogy.

Kemeka Sidbury serves as a sixth grade middle school math and science teacher, and she is also advancing her role as educational leader through the University of North Carolina at Wilmington MSA add-on licensure program. As an educational leader, her interests include content integration, school-community partnerships, and culturally relevant pedagogy.  Tamika Bierlein serves as the eighth grade middle school math and science teacher. Her interests include environmental education and providing children with new opportunities to be creative and impact the world around them.

Tamika Bierlein serves as the eighth grade middle school math and science teacher. Her interests include environmental education and providing children with new opportunities to be creative and impact the world around them.  Sohail Sukhera is a graduate student at the Watson College of Education of the University of North Carolina Wilmington. A current instructor at the local community college, his interests include home gardening and growing gourmet mushrooms.

Sohail Sukhera is a graduate student at the Watson College of Education of the University of North Carolina Wilmington. A current instructor at the local community college, his interests include home gardening and growing gourmet mushrooms.  William Sterrett served as a professor and associate dean at the University of North Carolina Wilmington. He now serves as professor and chair at Baylor University. A former principal and middle grades science teacher, his interests include collaborative school leadership, school-university partnerships, and green schools.A former principal and middle grades science teacher, his interests include collaborative school leadership, school-university partnerships, and green schools.

William Sterrett served as a professor and associate dean at the University of North Carolina Wilmington. He now serves as professor and chair at Baylor University. A former principal and middle grades science teacher, his interests include collaborative school leadership, school-university partnerships, and green schools.A former principal and middle grades science teacher, his interests include collaborative school leadership, school-university partnerships, and green schools.