Beyond the Monoculture: Strengthening Local Culture, Economy and Knowledge

OPINION

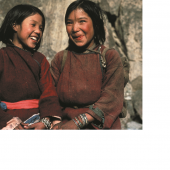

In this deeply cohesive and fundamentally geographic argument, Helena Norberg-Hodge brings an impressive array of sustainability issues under a single guiding rubric for educating and changing society—the need for a shift from globalised systems to local practice. While every point in her argument is backed with interesting details—including her fascinating experiences with the Himalayan Ladakhi people—she is consistent in bringing us back to valuing localisation and yet measured in her prescription which calls for gradual shifts, not radical and potentially harmful jumps, towards localisation.

Introduction

Despite the fact that almost every news item today brings information about the seeming endless list of crises, there is hope that we have the power to turn things around. In recent years, more and more people are waking up to the root causes behind our problems—from global warming and species extinction to fundamentalism and fear. If we stand back and look at the bigger picture, we will see that all these crises are connected to the globalised economy. Although it may initially be difficult to perceive, the economic system underpins almost every aspect of our lives today—from our jobs to the food we eat, the state of the environment to the state of education, politics to health.

Our system of education, scientific research and the development of new technologies have all been shaped by a fossil fuel-dependent global economic model. Economic globalisation, with its massive, centralised system of production and distribution, is transforming unique individuals into mass consumers, and homogenising diverse cultural traditions around the world. It is destroying wilderness and biodiversity, and creating an expanding stream of waste that the biosphere simply cannot absorb. It is widening the gap between rich and poor worldwide, and leading to increased levels of crime and violence. In the name of ‘growth’ and ‘efficiency’, it is dividing us from each other and from the natural world on which we ultimately depend.

Despite the apparent enormity of the task of making changes to our economic system, isolating this root cause can actually be very empowering. Rather than confront an overwhelming list of seemingly isolated symptoms, we can begin to discern the disease itself. Just as importantly, the outline of a cure starts to take shape as well. Localisation is a positive and realistic alternative to economic globalisation. Along with many others, I believe it is the best way to ensure our future wellbeing and that of the planet. One of the key steps to localising our economies is rebuilding local knowledge. It is an antidote to the global monoculture and the foundation of healthy, happy individuals and communities.

Globalised Knowledge

Today’s global economy is based primarily on abstract knowledge, divorced from our natural and cultural surroundings. It has allowed us to build a system of production and consumption that is entirely incompatible with natural ecosystems. It has increased our sense of being separate and distant from each other. We get news from Iraq, Japan or Washington, D.C.; at the touch of a button on a TV remote control, we have access to all the wildlife of Africa, and our immediate surroundings consequently seem dull and uninteresting by comparison. But this knowledge is made up of flat abstractions. It is not the sort of intimate knowledge gained through face to face interaction. People and places are reduced to abstract, simplistic concepts. In this way, the globalised media enables us to build up false generalisations of people from different cultures, thereby breeding prejudice, racism and fear.

The global economy has built a monoculture of ideas and consumer goods and is foisting them on people in every corner of the world. Nearly everywhere you go in the world today, you will find multi-lane highways, concrete cities and a cultural landscape featuring grey business suits, fast-food chains, Hollywood films and cellular phones. In the remotest corners of the planet, Barbie, Madonna and the Coke can are familiar icons. From Cleveland to Cairo to Caracas, CSI:Miami is entertainment and CNN is news. As a result, villages, rural communities and their cultural traditions are being destroyed on an unprecedented scale by the impact of globalising market forces. Communities that have sustained themselves for hundreds of years are simply disintegrating.

Conventional ‘development’ brings tourism, Western films and products and, more recently, satellite television to the remotest corners of the Earth. All provide overwhelming impressions of luxury and power. Advertising and action films give the impression that everyone in the west is rich, beautiful and brave, and leads a life filled with excitement and glamour. In the commercial mass culture which fuels this illusion, advertisers make it clear that Westernised fashion accessories equal sophistication. In diverse ‘developing’ nations around the world, people are induced to meet their needs not through their community or local economy, but by trying to buy in to the global market.

Even more damagingly, people are encouraged to reject their own ethnic and racial characteristics – to feel shame about who they are. Around the world, blonde-haired blue-eyed Barbie dolls and thin-as-a-rake ‘cover girls’ set the standard for women. The one-dimensional, fantasy view of modern life promoted by the Western media, television and business becomes a slap in the face for young people in the ‘Third World.’ Teenagers, in particular, are made to feel stupid and ashamed of their traditions and their origins. The people they learn to admire and respect on television are all ‘sophisticated’ city dwellers with fast cars, designer clothes, spotlessly clean hands and shiny white teeth. Yet they find their parents asking them to choose a way of life that involves working in the fields and getting their hands dirty for little or no money, and certainly no glamour. It is hardly surprising, then, that many choose to abandon the old ways of their parents for the siren song of a Western material paradise.

Learning from Ladakh

My experience in Ladakh has been a vivid, if painful, example of this destructive process at work. Ladakh is a remote, region in the Himalayas. Politically part of India, it shares more cultural similarities to Tibet. When I first arrived, over 35 years ago, the vast majority of Ladakhis were self-supporting farmers, living in small, scattered settlements in the high desert. Though natural resources were scarce and hard to obtain, the Ladakhis had a remarkably high standard of living – with beautiful art, architecture and jewellery. They worked at a gentle pace and enjoyed a degree of leisure unknown to most people in the West. Most Ladakhis only really worked for four months of the year, and poverty was an alien concept.

During my time in Ladakh it became clear to me that this traditional nature-based society was far more sustainable, both socially and environmentally than the Western consumer society I had been living in. The old culture fulfilled fundamental human needs while respecting natural limits. The various connecting relationships in the traditional system were mutually reinforcing, encouraging harmony and stability. Most importantly, I am convinced that Ladakhis were significantly happier before the arrival of western-style development in the mid-1970s than they are today.

To integrate Ladakh into the Indian, therefore global economy, the government built a paved road into the area. Suddenly, Ladakhis were subject to an avalanche of imported goods, Western media and propaganda extolling the virtues of everything from DDT to Jersey cows to hydroelectric dams. “Development” also brought westernised education. Now, instead of spending the growing season alongside the rest of their community, children were separated into age groups and forced to sit inside learning times tables.

No one can deny the value of real education, that is, the widening and enrichment of knowledge. But today education has become something quite different. It isolates children from their culture and from nature, training them instead to become narrow specialists in a Westernised urban environment. In Ladakh, modern schooling acts almost as a blindfold, preventing children from seeing the context in which they live. They leave school unable to use their own resources, unable to function in their own world.

For generation after generation, Ladakhis grew up learning how to provide themselves with clothing and shelter; how to make shoes out of yak skin and robes from the wool of sheep; how to build houses out of mud and stone. Children were given an intuitive awareness that allowed them, as they grew older, to use resources in an effective and sustainable way. None of that knowledge is provided in the modern school. Children are trained to become specialists in a technological, rather than an ecological, society. School is a place to forget traditional skills and, worse, to look down on them.

The basic curriculum is a poor imitation of that taught in other parts of India, which itself is an imitation of British education. There is almost nothing Ladakhi about it. Once, while visiting a classroom in Leh, I saw a drawing in a textbook of a child’s bedroom that could have been in London or New York. It showed a pile of neatly folded handkerchiefs on a four-poster bed and gave instructions as to which drawer of the vanity unit to keep them in. For homework, one of my young friends was supposed to figure out the angle of incidence that The Leaning Tower of Pisa makes with the ground. Another time she was struggling with an English translation of the Iliad.

With the exception of religious training in the monasteries, the traditional culture had no separate process called “education.” Education was the product of an intimate relationship with the community and its environment. Children learned from grandparents, family, and friends. Helping with the sowing, for instance, they would learn that on one side of the village it was a little warmer, on the other side a little colder. From their own experience children would come to distinguish between different strains of barley and the specific growing conditions each strain preferred. They learned to recognise even the tiniest wild plant and how to use it, and how to pick out a particular animal on a faraway mountain slope. They learned about connections, process, and change, about the intricate web of fluctuating relationships in the natural world around them.

The importance of experiential knowledge is evident in the Ladakhi language itself. Compared with any Western language that I know, Ladakhi seems to put a greater emphasis on relativity. The language obliges one to express more of the context of what one is trying to say. Most strikingly, the verb to be has more than twenty variations, depending on the specifics of the situation—in particular, on the relative intimacy of both the speaker and the listener with the subject matter. Unlike Westerners, Ladakhis never express themselves with certitude about something they have not experienced. Any event in which they have not personally participated will be described using verbs that reflect the limitations of their knowledge.

In every corner of the world today, the process called ‘education’ is based on the same assumptions and the same Eurocentric model. The focus is on faraway facts and figures, a supposed universal knowledge. The books propagate information that is meant to be appropriate for the entire planet. But since only a kind of knowledge that is far removed from specific ecosystems and cultures can be universally applicable, what children learn is essentially synthetic, divorced from the living context. If they go on to higher education, they may learn about building houses, but these houses will be of concrete and steel, the universal box. So too, if they study agriculture, they will learn about industrial farming: chemical fertilisers and pesticides, large machinery and hybrid seeds.

In Ladakh, modern education not only ignores local resources, but, worse still, makes children think of themselves and their culture as inferior. They are robbed of their self-esteem. Everything in school promotes the Western model and, as a direct consequence, makes them ashamed of their own traditions. Education pulls people away from agriculture into the city, where they become dependent on the money economy. In traditional Ladakh there was no such thing as unemployment. But in the modern sector there is now intense competition for a very limited number of paying jobs, principally in the government. As a result, unemployment is already a serious problem.

Modern education has brought obvious benefits, like improvements in the rate of literacy and numeracy. It has also enabled the Ladakhis to be more informed about the forces at play in the world outside. However, it has divided Ladakhis from each other and the land and put them on the lowest rung of the global economic ladder.

The Western educational system is making us all poorer by teaching people around the world to use the same resources, ignoring those of their own environment. In this way education is creating artificial scarcity and inducing competition. It gives most of us the knowledge useful only for becoming anonymous producers and consumers in the globalised economy, where jobs are limited. Basic local knowledge, such as how to build your own shelter or grow your own food—skills that have ensured the survival of humans for millennia—have become the domain of specialists.

Eroding cultural integrity and self-esteem

The main agents of conventional development—education, tourism and media—combine in an almost unstoppable force that dissolves cultural integrity and individual self-esteem. As they lose the sense of security and identity that springs from deep, long-lasting connections to people and place, the Ladakhis are starting to develop doubts about who they are. The images they get from outside tell them to be different, to own more, to buy more and to thus be ‘better’ than they are. The previously strong, outgoing women of Ladakh have been replaced by a new generation – unsure of themselves and desperately concerned with their appearance. And as their desire to be ‘modern’ grows, Ladakhis are turning their backs on their traditional culture. I have seen Ladakhis wearing wristwatches they cannot read. Even traditional foods are no longer a source of pride; now, when I’m a guest in a Ladakhi village, people apologise if they serve the traditional roasted barley, ngamphe, instead of instant noodles.

Ironically, then, modernisation – so often associated with the triumph of individualism – has produced a loss of individuality and a growing sense of personal insecurity. As people become self-conscious and insecure, they feel pressured to conform, and to live up to an idealised image. By contrast, in the traditional village, where everyone wore essentially the same clothes and looked the same to the casual observer, there was more freedom to relax. As part of a close-knit community, people felt secure enough to be themselves.

In Ladakh, as elsewhere, the breaking of local cultural, economic and political ties isolates people from their locality and from each other. At the same time, life speeds up and mobility increases – making even familiar relationships more superficial and brief. Competition for scarce jobs and political representation within the new centralised structures increasingly divides people. Ethnic and religious differences began to take on a political dimension, causing bitterness and enmity on a scale hitherto unknown. With a desperate irony, the monoculture creates divisions that previously did not exist.

As the fabric of local interdependence fragments, so do traditional levels of tolerance and co-operation. In villages near the capital, disputes and acrimony within previously close-knit communities, and even within families, are increasing. I have even seen heated arguments over the allocation of irrigation water, a procedure that had previously been managed smoothly within a co-operative framework. The rise in this kind of new rivalry is one of the most painful divisions that I have seen in Ladakh. Within a few years, growing competition had actually culminated in violence – and this in a place where, previously, there had been no group conflict in living memory. Ladakh is not an isolated example. Wherever I go in the world, people from “developing” nations tell me that the same process is happening in their own communities.

The impacts of the global monoculture on our wellbeing are equally apparent in Western countries. The number of people suffering from depression has reach record levels in Western countries. And, it is not only adults who are affected. An estimated five million American children are being given at least one psychiatric drug. This disturbing trend is growing rapidly. The number of children ages 2-4 for whom stimulant and anti-depressant drugs have been prescribed increased 50 percent between 1991 and 1995. In the following four years, prescriptions for anti-depression drugs rose even more steeply, climbing 151 percent for children in the 7-12 age group, and 580 percent for children six and under.

The number of pre-pubescent children with eating disorders is on the rise, with girls as young as four showing signs of anorexia. Cosmetic surgery, another symptom of insecurity and poor self-image, is also on the increase, with the number of teen-age girls having their breasts augmented quadrupling, and liposuction procedures tripling, in just the past five years. Violence is also on the rise. In the last decade there have been more than thirty school shootings in the US. The youngest killer was a six-year old boy.

As corporations scour the world for bigger subsidies and lower costs, jobs move with them, and families as well: the typical American moves eleven times during their life, constantly severing connections between relatives, neighbours and friends. Within almost every family, the economic pressures on parents systematically rob them of time with even their own children. Americans put in longer hours at work than people in any other industrialised country, and the trend is ever upward. As a consequence more and more young children are relegated to the care of strangers in crowded day-care centres. Older children are often left in the company of violent video games or the corporate sponsors of their favourite television shows. Time spent in nature – fundamentally important to our psychological well being – is increasingly rare.

Globalisation and the spreading consumer culture thus work to displace the flesh-and-blood role models – parents and grandparents, aunts and uncles, friends and neighbours – that children once looked up to, replacing them with media and advertising images: rakish movie and rock stars, steroid-enhanced athletes and airbrushed supermodels. Children who strive to emulate these manufactured ‘perfect’ idols are left feeling insecure and inadequate. It is not surprising that American children, many of whom seem to ‘have everything’, are so unhappy: like their parents, their teachers at school and even their television heroes, they have been put on a treadmill that is ever more stressful and competitive, ever more meaningless and lonely.

In the UK, the statistics tell a similar story. In 2004, nearly 10% of children between the ages of 5 and 16 had a mental health disorder and that figure is increasing. Substance abuse and violence are also on the rise. Recently, a group of experts gathered together to publicise their concerns that modern life and “junk culture” are poisoning childhood. The Archbishop of Canterbury has accused entertainment companies of creating a consumer culture where children are corrupted and “sexualised”. Sue Palmer, the author of Toxic Childhood, points out that “a sort of sedentary, screen-based existence has crept up on children. They used to be free-range and now they’re practically battery children, living indoors, experiencing through the medium of a screen. That, along with the food that they’re eating, many of them in great quantities now, actually is inhibiting brain development.”

Localising Knowledge

Unless the consumer monoculture is halted there is no hope of preventing ever-greater poverty, social divisiveness, and ecological degradation. There is nothing inevitable about this process of globalisation. It is entirely within our power to shift direction–to rebuild local economies and communities, to protect our natural resources and to ensure peace and security. In addition to opposing technological uniformity, we need to actively support ecological and cultural diversity by encouraging the fullest possible use of local resources, knowledge, and skills.

Revitalising local knowledge is essential to localisation. Without retreating into cultural or economic isolationism we can nourish the traditions of our own region. A true appreciation of cultural diversity means neither imposing our own culture on others, nor packaging, exploiting, and commercialising exotic cultures for our own consumption. One of the most effective ways of reviving cultural differences would be to lobby for a reduction in unnecessary trade. At the moment, much of our taxes are going to expand transport infrastructures and to increase trade for the sake of trade. We are transporting across whole continents a vast range of products, from milk to apples to furniture, which could just as easily be produced in their place of destination. By reducing and eliminating subsidies for transportation, we would cut waste and pollution, improve the position of small farmers, and strengthen communities in one fell swoop.

Local agricultural knowledge is essential to knowing which crops are adapted to the local environmental conditions. Producing food with this sort of intimate understanding of the land and climate enables farmers to work in a much more sustainable and efficient way. It is in robust, local-scale economies that we find genuinely “free” markets; free of the corporate manipulation, hidden subsidies, waste, and immense promotional costs that characterise today’s global market.

Paradoxically, a trend toward smaller-scale political and economic units would help us to develop a broader world view—one based on interconnectedness. Instead of narrowing our vision, an intimate connect ion to community and place would encourage an understanding of interdependence. When you are dependent on the earth under your feet and the community around you for your survival, you experience interdependence as a fact of daily life. Such a deep experiential understanding of interconnectedness—feeling yourself a part of the continuum of life—contrasts starkly with the analytic, fragmented, and theoretical thinking of modern society.

Since extreme dependence has already been created on both national and international levels, it would be irresponsible to “delink” economies and cut off assistance from one day to the next. We cannot, for example, suddenly halt our purchase of coffee or cotton from those countries in the Third World whose economies totally depend on such trade. But we can immediately begin supporting aid programs that will enable farmers to return to growing food for local consumption, rather than cash crops for export to the West.

Parallel to agricultural decentralisation we need to decentralise the production of energy. Again, this ought to happen both in the West and in the Third World, but because the energy infrastructure of most developing countries is still relatively limited, the widespread application of solar, wind, biomass, and hydropower technologies in these regions would be comparatively easy. Truly appropriate technology would be far less costly than “high” technology—not just in purely economic terms but, very importantly, in its impact on society and the environment. It would be born of research in specific social and geographical settings, and be tailored to them, rather than vice versa. As anyone who has been close to the land knows, variations in wind, water, sun, soil, and temperature are significant even within very short distances. Just as brick-making in Ladakh varies from region to region, depending on the type of mud available, so small-scale installations adapted to local conditions are required if we are to make optimum use of available resources. This would entail a listening, intimate knowledge of nature—a very different approach from the heavy-handed ways of industrial society.

If development is to be based on local resources, knowledge about those resources obviously needs to be nurtured and supported. Instead of memorising a standardised universal knowledge, children need to be given the tools to understand their own environment. In the process, the narrow specialisation and urban orientation of Western-style education would give way to a broader, more contextual and ecological perspective. Location-specific knowledge of this kind would be holistic and specific at the same time. Such an approach would seek to perpetuate or rediscover traditional knowledge. It would build on centuries of empathetic interaction and experience with the web of life in a particular place.

Support for local knowledge should extend to all areas of education, including the natural sciences. We need to promote research that is less centralised and more accessible to a broader section of the population. Instead of isolating variables under artificial laboratory conditions, emphasis would be placed on experimentation by local researchers in diverse cultural and ecological environments. Rather than maintaining elaborate high-tech seed banks, for instance, farmers would be encouraged to grow rare indigenous varieties, thus perpetuating living reservoirs of biological diversity.

To understand the complexities of the natural world, theory must be grounded in experience. Experiential learning is based in messy reality, with all its paradox and untidiness, its ever-changing pattern, its refusal to conform to our expectations. As such, it inevitably leads to humility. If our studies were conducted less in the laboratory and more in the field—in the fields, in fact—scientific advance would proceed more cautiously. If we learned to examine the potential effects of new technologies in context, over time, we would be less likely to set off destructive chains of unintended effects.

In the West, we tend to live our lives at one remove from reality, relying on images and concepts. After spending a few months in England, a Ladakhi friend of mine commented, “It’s amazing how indirect everything is here. They write about the beauty of nature, they talk about it, and everywhere there are potted plants and plastic plants, and pictures of trees on the wall. And all the time television programs about nature. But they don’t ever seem to have contact with the real thing.”

However, there are signs of a shift happening around the world. Many initiatives are emerging that reconnect people with place. In Scotland, a teacher of twenty years has set up a nursery, where children spend most of the day, everyday outdoors. Dressed in rubber boots and woolly jumpers they play and learn in sun, rain and snow. According to parents, the children not only love it, they acquire valuable knowledge. Before they even graduate to primary school, the children can distinguish poisonous from edible fungi, can spot yew berries or foxgloves, the flowers that contain the toxin digitalis. The teacher explains that “in a normal nursery you might have to learn about shapes, but these children know the difference between an oak tree and a birch tree, which is a lot more complex than a square and a circle.”

More and more people are reconnecting with the sources of their food. Farmers’ markets, which shorten the distance between producer and consumer, are springing up, while around the world thousands of individuals and organisations are exploring locally based, sustainable alternatives, often inspired by the proven success of traditional agricultural systems. Official support, however, still lags a long way behind. Although there are encouraging signs that governments are recognising the need for a move toward organic agriculture, economic incentives continue to favour biotechnology and large-scale agribusiness.

However, people are beginning to make their voices heard. For example, individuals and groups from a wide variety of sectors are coming together to protest the privatisation of water. All around the world—from Argentina to Australia, the UK to Portugal, Norway to Uruguay—trade unions, community groups and environmental activists are demanding that access to clean water be designated as a fundamental human right. They propose that control over water be kept in the hands of the public, managed at the local level, rather than owned as a commodity by corporations and doled out at prohibitive prices.

There are even positive moves toward supporting cultural diversity at the policy level. In 2007, UNESCO’s Convention on the Protection of Diversity of Cultural Expressions came into force. Thirty-five countries—“developed” and “developing” — ratified this text that aims to re-establish the connections between local culture, development and dialogue. For future development to progress in a way that is adapted to needs of people, culture and the environment, the convention affirms the rights of countries “to protect and promote the diversity of cultural expressions” and “to create the conditions for cultures to flourish and to freely interact in a mutually beneficial manner.”

Local economies are much more than utopian ideals; they have served admirably in many parts of the world for millennia. They tend toward a more equitable distribution of wealth than growth-oriented centralised systems, and are more responsive to the needs of people and the limitations of natural resources.

Conclusion

The changes that we need to make can greatly enrich our lives. Yet they are often treated, even within the environmental movement, as sacrifices. The emphasis is on giving things up and making do with less, rather than recognising how much we stand to gain. We forget that the price for never-ending economic growth and material prosperity has been social impoverishment, psychological insecurity, environmental crises and the loss of cultural vitality. We think of ourselves as “having everything,” and are surprised when young people turn to drugs or violence to fill the void in their lives.

We still have an opportunity to steer our society toward social and ecological balance.

I have seen how human-scale structures nurture intimate bonds with the earth and an active and participatory democracy, while supporting strong and vital communities, healthy families, and a greater balance between male and female. These structures in turn provide the security needed for individual well-being and, paradoxically, for a sense of freedom.

Perhaps the most important lesson of Ladakh has to do with happiness. It was a lesson that I was slow to learn. Only after many years of peeling away layers of preconceptions did I begin to see the joy and laughter of the Ladakhis for what it really was: a genuine and unhindered appreciation of life itself. In Ladakh I have known a people who regard peace of mind and joie de vivre as their unquestioned birthright. I have seen that community and a close relationship to the land can enrich human life beyond all comparison with material wealth or technological sophistication.

Rekindling local knowledge opens us up to a world of richness and diversity. It is a fundamental step towards dismantling the global monoculture, healing our societies and rebuilding local economies. Localisation ultimately helps to ensure the wellbeing of ourselves, our communities and the planet.

Helena Norberg-Hodge is founder and director of The Ladakh Project and the International Society for Ecology and Culture (ISEC). A pioneer of the ‘new economy’ movement, she has been promoting an economics of personal, social and ecological well-being for more than thirty years. She is author of Ancient Futures and producer and co-director of The Economics of Happiness.

Helena Norberg-Hodge is founder and director of The Ladakh Project and the International Society for Ecology and Culture (ISEC). A pioneer of the ‘new economy’ movement, she has been promoting an economics of personal, social and ecological well-being for more than thirty years. She is author of Ancient Futures and producer and co-director of The Economics of Happiness.

When it comes to information – sometmes less is more. In this case, more is more, and it’s all good. Thank you.

Dear Helena, I couldn’t agree more –

the UNESCO declared in 2001 that cultural preservation is as important for human mankind as ecological preservation.

The knowledge, wisdom, values that we are loosing every day as a global society are immense.

and what happens when we loose our roots, our identity as a society can be seen in our western world – we loose touch with ourselves at the end and are now looking for new “methods” to be re-rooted.

I am working in Morocco – in the Atlas mountains with the berbers – and I made similar experiences like you explained –

we are trying to help them to be proud of their culture and to keep it. It is such a gift to be able to be and work with these people over a long period of time – there is so much to learn for both of us – and at the end it is a win-win situation if we are open and curious enough :)!

This is the most interesting, informative, thought-provoking, fantastic article I have read for a long-long time.Thank you Helena for sharing!

Completely agree with this!!