We are where we are from: Flaneurism and writing about walking our streets

Friesen JSE Dec 2018 General Issue PDF

Abstract:Reynolds (2004) says we write from where we are (p. 53). What does that mean? In a class called Composing our City, place, place-based learning, and place-based projects were the sustainable modus operandi. We wrote, thought, and created where we are from. As we engaged in place-based learning, we touched on topics like the emotions places evoke, how environments come with a sense of place, learning the art of flaneurism, and how crossing borders in our assignments teaches us aspects about our environments and ourselves we could not learn otherwise. Flaneurism was our method of collecting data and the object of our writing, as we explored, described, and discovered where we are from.

Keywords: Flaneurism, Landscape, Place-based learning, Space, Streets, Writing

Introduction

What does Reynolds (2004) actually mean when she says we write from where we are (p. 53)? We don’t live in boxes with blank walls. We don’t live in our heads with ideas floating around like skittish transparent abstract constructions. Our life happens in neighborhoods, on streets, and in interactions with people along the way: at the 8 a.m. bus stop waiting in the cold winter wind, squeezed into a crowded 5 p.m. bus listening to a one-sided conversation in Hindi or Spanish, in the produce aisle at the grocery store contemplating lettuce and spinach, on a walk around the park with a beagle tugging at the leash, waiting in line at a local ice cream shop at twilight on a humid summer day, or talking with neighbors while raking caked brown grass after the winter has melted away. Where we live influences our thinking, doing, and imagining. Some places and people can leave a neutral impression that does not sway us one way or another, but usually, interactions leave an emotional impression on the scale of 1 to 10 where 1 is awful, and 10 is exuberant. Reynolds (2004) says:

As Plato knew and as I explore here, memory and place, location and argument, walking and learning, are vitally and dramatically linked in our personal histories and personal geographies. Places evoke powerful human emotions because they become layered, like sediment or a palimpsest, with histories and stories and memories. When places are inhabited in the fullest sense, they become embodied with the kinds of stories, myths, and legends that the spot beside the Ilissus holds; they can stimulate and refresh—or disturb and unnerve—their visitors. (p. 2)

This past year I was tasked with teaching a course in our department called Composing our City. Throughout the semester, the whole city came alive as our canvas, our walking route, our topic of analysis, and our project with which to test urban design theories. We explored layers, histories, myths, and memories in eating establishments, underground tunnels, murals, the music scene, city design, architecture, and local businesses. Some of our explorations unnerved us, some refreshed us, some disturbed us, and none left us the same as before we started our walking and learning. We all took the learning home and came back the next day with observations from our personal life that matched or mismatched the theories we were discussing and writing about in class.

We talked to city planners, historians, business developers, and architects to learn about how our city and streets work. Topics of analysis included: murals, sidewalks, shops, streets, pedestrians, public characters, cars, and borders. We talked and wrote about things like feeling out of place in certain parts of the city and certain times of day and analyzed the reasons for those feelings. We were surprised by things we had never noticed before and we all were surprised that Jane Jacobs’ observations from the 60s were still relevant today, but we all disagreed with her rather disparaging stance on parks. Place, place-based learning, and place-based projects as the modus operandi in our class was probably the most sustainable method and topic I had ever encountered in a university class. Sometimes we just had too many things to talk about. As we engaged in place-based learning, we touched on topics like the emotions places evoke, how environments come with a sense of place, learning the art of flaneurism, and how crossing borders in our assignments teaches us aspects about our environments and ourselves we could not learn otherwise. Seal (2013) describes a flaneur as a casual wanderer that explores, observes, and reports on the life of the modern city. Flaneurism was our method of collecting data and the object of our writing as we explored, described, and wrestled with where we are from.

Place evokes emotion

Exploration of places and cities evokes emotions based on many factors. Creswell (2015) says that “the creation of ‘nice places to live’ is one of the central ways in which places are produced” (p.135). How places are produced depends on the producer and those productions can vary dramatically depending on many variables such as race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, experience, and history.

How have other people portrayed our city? What emotions do the people evoke that write and talk about our city? What impression do people give of our city? Images of our city are spread every day in the local papers, in conversations about real and imagined experiences, and in stories that show one side of a story or a completely different side of the same story. I recognize that my article is just like that. It shows one side of flaneurism and one subjective view and understanding of flaneurism. Guy Maddin’s My Winnipeg is a different Winnipeg from Indian City’s or the Whiteout street parties of the spring of 2018 when the Winnipeg Jets were playing in the Stanley Cup playoffs.

Guy Maddin’s 2008 documentary about Winnipeg portrays a sleepy and dreamy Winnipeg that never seems to wake up. In a black and white fuzzy documentary to the background sound of train tracks and train whistles, Guy Maddin talks about Winnipeg as “the snowing, sleepwalking Winnipeg. My home my entire life. I need to get out of here. I must leave it now.” Although trying to extol humour in a depressing way, his representation of Winnipeg is suffocating that would not exactly attract newcomers to stay. What are some emotions that places evoke? It depends who you talk to and who you listen to.

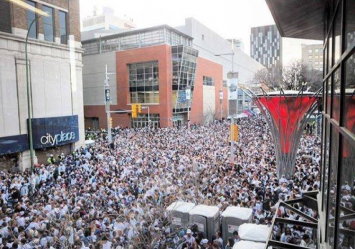

As I write this, the Winnipeg Jets, the professional National Hockey League (NHL) hockey team is playing in the Stanley Cup playoffs. The playoff series consists of the best of seven games. The teams alternate two home and two away games. The Winnipeg Jets made it to the final eight for the first time in their history. The whole city is painted with Jets fever, where Go Jets Go is blazoned on most businesses, buses, and homes. When the home games are in Winnipeg, the city organizes huge streets parties blocking off city blocks downtown and setting up huge projectors to air the game live for free, outside of the home ice arena, the MTS Centre. Donned in Jets jerseys, fans crowd the streets like one big live cheering organism of Winnipeg pride. Whiteout parties suddenly attract thousands of people to an otherwise sleepy and sometimes seen as dangerous downtown in the evenings.

Jane Jacobs (2011) talks about multiuse of streets and sidewalks. “The livelier and more popular a sidewalk, and the greater the number and variety of its users, the greater the total width needed for it to serve its purpose pleasantly (Jacobs, 2011, p. 87). In the spring of 2018, the sidewalks in downtown Winnipeg extended to envelope the streets. Although downtown streets were not built for massive street parties like the Whiteout parties, suddenly they turned from cars-only thoroughfares to venues for a grand pedestrian-only street party for up 23,000 fans, complete with a parade of food trucks, First Aid bus, security, hot and corn dog stands, fences, and stands for handicap accessibility. This also is our Winnipeg, a complete and total opposite of Guy Maddin’s sleepy Winnipeg. This is a Winnipeg that is bursting with pride, with no intention of leaving or wanting to leave. In the Winnipeg Whiteout street parties, a crew of 100 people spend all day setting up and taking down the party (Gibson, 2018). “With every broadcast of Winnipeg Jets home games during this season’s playoff run, the rest of the continent is learning something people in this city have known for a long time. Winnipeggers know a thing or two about throwing proper parties” (Gibson, 2018). “Competing notions of public space result, of course, from different ideological positions… Spaces are continually being remade, used in different ways, and that there are possibilities for resisting the control of public space” (Reynolds, 2004, p. 25, 26). Currently, space is being remade on Winnipeg’s streets.

(Byren Gregorchuk/@fortheloveofwinnipeg/Instagram) Retrieved from http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/manitoba/white-out-party-planning-1.4650518

Winnipeg is a city of many faces. Another face is Indian City, an award-winning Canadian Folk Pop band that brings the Indigenous voice and story to life through lyrics, personality, and music (Indian City), the opposite of Guy Maddin’s sleepy Winnipeg and very different from the Whiteout street parties. These are three distinct faces, and they all compose Winnipeg emotions. Winnipeg is located on Treaty 1 land; the original lands of the Anishinabe, Cree, Oji-Cree, Dakota and Dene peoples, and on the homeland of the Metis nation, where reconciliation between Indigenous and nonIndigenous peoples is a struggle and concern. Indian City’s Juno award-winning Indigenous Music Album of the year Here and Now addresses those current issues and concerns. The Juno awards honor the best in Canadian music (Thiessen, 2018). The rest of the country is hearing the message and recognizing the importance. Their lyrics speak about issues that pertain to all people’s struggle (Indian City, 2018). Resisting politics of domination and working towards embodying politics of transformation is what hooks (1999) writes about “in a manner that clearly names the concrete strategies for radical and/or revolutionary interventions. She also “addresses the concerns of individuals and communities in resistance” (p. 7) where there is the pressure to conform. “This is especially true of any dissenting voice that remains within a hierarchical institution founded on structures of domination where rewards and benefits are awarded in relation to service rendered. However, irrespective of our locations, we are all vulnerable” (hooks, 1999, p. 7). Some citizens experience more vulnerability than others. Our socioeconomic status, our race, our heritage, our history all impact our emotional connection to the place we call home.

Environments come with a sense of place.

Creswell (2015) says that “it would be wrong to romanticize this sense of place as always rosy and “homelike” (in the idealized sense of home). Some places are evil, oppressive, and exploitative” (p. 55). Others experience place as liberating and cathartic. How people experience place depends on their social location and the political climate of their environment. How do we read landscape as a text to get a sense of place? Not only do local award-winning bands, sports teams, and artists represent home on a bigger stage, we all represent and interact with our environment in a unique way to arrive at a sense of place.

While I write where I am from, my husband carves where he is from. On his walks through the park in our neighborhood, he keeps his eye open for driftwood and fallen trees, which all become potential art projects. A large piece of driftwood from the Red River became our coffee table.

Dead branches scavenged from a nearby park became lamp stands, a log became a goose sculpture for our anniversary. Recently in my walk through the park, I noticed artistic rock messages someone had left in the nook of a tree.

It prompted me to pick up a piece of nature

and paint a response. Creswell (2015) states that “the kinds of places we inhabit – favorite rooms, neighborhoods, nations – are all indeed analyzable as social products” (p. 55). We all exist in a place. Adopting a flaneur role gives us the tool and space to analyze and then write about things in our environment like driftwood, pieces of bark, and happy messages.

I felt like I was having a conversation with Reynolds (2004) when she says,

Many of our experiences in life “take place” in a location, and then we draw upon characteristics of those locations to construct memories and to judge or respond to other places. Because homes, neighborhoods, parks, cafes, or classrooms can be so emotionally loaded, it’s difficult, methodologically, to study the relationships of people and places, or to understand how some places can feel like home to some while alienating others. But it is urgent for us to consider how spaces impact upon learning, reading, and writing when opportunities for communicating expand through electronic technologies while, at the same time, moving through the world seems more difficult or more dangerous. (p. 3)

I didn’t know who sent me the message to “bee happy” that day but I responded in the same language and medium. I participated in a dialogue with someone I did not know because I chanced upon a path in a park on a certain day to pick up the bark text in a nonelectronic medium. Suddenly I was in a relationship with a person, a place, an environment, and an object that became part of my home. Reynolds (2004) says,

On a smaller spatial scale, if we could discover more about how people learn about boundaries and borders, when they may cross them without penalty; or how they can slip in without being detected; or what the safe times of day are, then we could apply these findings to a richer understanding of how people learn to read, write, and interact with texts. Imagining acts of writing as material—carving text out of time and space, in particular circumstances that differ for each writer—opens up new spaces in which to study and understand literacy and the construction of meaning. (p. 3)

Literacy can be as small as painting a one or two-word message on a rock or piece of bark and putting it back in the place it came from to communicate with other flaneurs that walk the same path I do, but just at a different time of day. The artist carved a unique text out of time, space, and medium that made me smile that day. My environment established a sense of place that prompted me to interact with nature in a way I had never done before. Although my crossing the border was of minimal consequence, I fully realize that in other situations, crossing a border comes with more substantial consequences.

The art of flaneurism

In university, we try to equip students with tools that will help them make their way through life. One way we can do that is to talk about being flaneurs. Reynolds (2004) says, “Although geographers do not have a monopoly on “seeing” as a research practice, they might suggest that understanding spatial and cultural difference begins on the ground, for example, by walking through neighborhoods” (p. 69). “Learning to see takes place at street level, through walking. While other ways of moving through the world might also teach us to see, only walking embraces so many senses and has the “hands on” (or feet first) materiality of place” (Reynolds, 2004, p. 69). Flanerie is not just an aimless wandering the streets and not just a cheap way of getting around; it is an art and an approach to observing, collecting, arranging, and writing about the world we see (Reynolds, 2004).

Reynolds (2004) says the main focus of the flaneur is to absorb the city, organize, and then compare, contrast the material just like we do with literary texts except that the text is our environment. Our writing about flaneurism is similar to literary analysis: define it, analyze it, understand its pathways, its secrets, its environment and how we interact with it. Strolling not running is important because in going too fast we may miss patterns and images. It may seem the flaneur is wasting time, but flaneurism requires time and careful attention to detail. “The flaneur is interested in “experience rather than in knowledge, a flaneur observes the habits of everyone, across classes and occupations” (Reynolds, 2004, p. 71). A flaneur would notice new businesses on the street, new people walking in the neighborhood like a stranger smoking in the woods on a dry day and contemplating warning him of the severe danger of accidental sparks causing a forest fire to burn down the neighborhood. Flaneurism is about seeing more than what we can see when we open our eyes. To be able to see raindrops on a new leaf in spring, you can’t be driving by, not even biking; you have to walk slowly because otherwise you will miss the wonder.

(Photo credit: Timothy Friesen)

Walking the streets and observing layers of life, sometimes require the use of maps so that we do not get lost, but sometimes getting lost teaches us things we could otherwise not learn. Working with maps is usually the work of geographers, but maps are also the work of rhetoricians. Reynolds (2004) talks about maps as providing information that prompts action. Maps are texts that “capture the layers of meaning and the feelings of residents or visitors or trespassers” (Reynolds, 2004, p. 109). Flaneurs may travel with or without maps. Sometimes maps show borders, but some borders are invisible.

Crossing Borders

Anzaldua (2012) says that “borders are set up to define the places that are safe and unsafe, to distinguish us from them. A border is a dividing line, a narrow strip along a steep edge. A borderland is a vague and undetermined place created by the emotional residue of an unnatural boundary. It is in a constant state of transition. The prohibited and forbidden are its inhabitants.” Indian City along with Anzaldua imagine a place where borders are erased, where everyone is welcome in every part of the city, where exclusion is a foreign word erased from people’s memory. In Stewart’s (2015) borderland doctoral dissertation, he “privileges indigenous architecture as indigenous peoples knowledges” and creates “a discursive space in which to discuss cultural / academic / professional / knowledge” (p. 6). He interviewed many indigenous architects to learn about their ideas for designs and solutions. By recognizing and accepting difference and complexity, Stewart (2015), in both content, design, and style, challenges conventional boundaries. In an interview with CBC reporter Lenard Monkman (2016), Cheyenne Thomas says, “Indigenous design is “one of the most innovative ways of thinking of the environment. We constantly have to adapt, we constantly have to rethink of how to exist in different ways.” Different ways offer a sense of place that is constantly changing and being reevaluated as borders expand and shift.

Reynolds (2004) talks about compositionbeing heavily invested “in imagined geographies while ignoring materialspaces; however, there is also a mutual dependence or an interconnectednessbetween the material and the metaphorical” (p. 7). During the time that I was teaching the Composing our City class, I visited for the first time Thermea Spa, that moved into our neighborhood about two or three years ago.

Our walks around the neighborhood always took us around the spa but never into it. For a Reading Week treat, my husband and I decided to explore the inside and see what it was like. My experience provided rich material for discussion. Thermea comes complete with both physical and metaphorical borders. There is only one entrance and that is at the front. Access from the back over the fence where we usually walk, would not be permitted. The next border is the entrance fee. Only visitors that can pay the entrance fee are allowed in. Dress code and behaviour are heavily regulated. Bathing suits and bathrobes are the dress code. Big signs with the code of conduct are displayed around the spa. Only quiet whispering allowed. Two of the rooms are public napping rooms, where soft music lulls people to sleep on mats or in the rounded chairs. The interconnectedness of the material and the metaphorical became evident. If I were stretched out on a park bench just outside the spa, passersby would probably stop and ask if I were ok, or they may even call the police to check on my wellbeing. Public napping is usually not acceptable behavior on a park bench, but completely acceptable once it is transported into a high-end spa. It made me wonder about who and how those borders get established and how they demand and expect respect. Public space is an interesting phenomenon and has changed with changing customs and routines.

Even the public space at universities is changing. A growing trend is to task students with experiential learning opportunities that take them out of the classroom. As instructors, we should embrace those learning opportunities as well. Even a visit to the spa can be an opportunity to put theories of place and space to the test. Leaving behind familiarity helps us understand differences. Positioning “the learner as an outsider, a foreigner, an other” can cause discomfort but can prompt struggle and reflection (Reynolds, 2004, p. 113). As flaneurs exploring “we are so intent on figuring out where the borders lie and who can cross them that we may be neglecting the places constructed by those borders” (Reynolds, 2004, p. 6). What kind of assignments do we construct for our students? Do they require memorization of inane unnecessary things that students will forget as soon as the test is finished? The right answer to be put in the right place at the right time? There is merit to memorization for sure, but merit also in arriving at questions instead of answers. What if student final assignments were constructed of challenges for them to come up with questions instead of the proverbial answer to the question? “Giving students the experience of a contact zone takes many forms, but one ofthe most common in recent years has been to send students “out of place,”by asking them to go to community centers or other locations outside ofthe university, and then, in one version, to write about their experiences there” (Reynolds, 2004, p. 113) One of my assignments in the Composing our City class was to implement flaneurism. The assignment was the following:

Experiential Learning Opportunity ELO

Word Count: 500 words

Objective:To gain hands-on research experience in analyzing the space and place where we live.

Choose a place where you would like to do your ELO. Spend at least one hour in the location observing or participating in an activity. Write a summary of what you learned. Include information like:

Place:

What have you observed?

What have you learned?

Other questions to consider:

How is space used?

How do you interpret the place?

What jumps out at you as you enter the space?

What themes emerge as you walk through the space?

What role do sidewalks play in this space? Art? Architecture? People?

How does the space represent the activity that goes on there?

Connect readings to practice.

These are just a few options. There are many others. Feel free to explore on your own to find a place you would like to describe and analyze.

- The Legislative Assembly of Manitoba

- Manitoba Indigenous Cultural Education Centre Inc.

- A specific neighbourhood

- A specific gathering place like The Forks Market

- A museum like the Museum for Human Rights

- Our university

- The train station

- Airport

- Mall

Going out onto the streets where we are from, opened our eyes to see and analyze aspects of our every day life that we were simply not aware of because we had not yet opened our eyes.

Conclusion

One day a few weeks after the beginning of the Composing our City, a few students were having a conversation about the class. One student said that when people asked her what the class was about, she was unsure how to respond. At the end of the class, we looked at each other and shared our enthusiasm and surprise for all the things we had learned. We had engaged in place-based learning, learned that places evoke emotions, that environments come with a sense of place, learned about the art of flaneurism by doing it, and how crossing borders in our assignments taught us aspects about our environments and ourselves we could not otherwise have learned. Flaneurism was our method of collecting data and the object of our writing, and through that we uncovered layers of where we are from that had been hidden until now. Flaneurism was like mining for place-based gold and depending on how slowly we walk and with how much wonder we expected, determined the quality of the experience. Composing our City could be just another class to check off the list, but it had the potential for transforming how we saw ourselves and the place where we are from.

References

Anzaldua, G. (2012). Excerpts from Borderlands/La Frontera. Retrieved on May 24, 2018 from

http://www.warscapes.com/retrospectives/uncertain-borders/excerpts-borderlandsla-frontera

Cresswell, T. (2015). Place: An Introduction. Second edition. ed., Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley, Blackwell.

Gibson, S. (May 6, 2018). Setting up, tearing down Winnipeg Whiteout Street Parties no small feat. CBC News.Retrieved on May 8, 2018 from http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/manitoba/white-out-party-planning-1.4650518.

Gregorchuk, B. (2018). Photograph. Retrieved on November 7, 2018 from http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/manitoba/white-out-party-planning-1.4650518

Hooks, b. (1999). Dancing with words. Originally published in Remembered Rapture: The

Writer at Work. New York: Henry Holt. Retrieved on May 25, 2018 from http://www.jaconlinejournal.com/archives/vol20.1/bellhooks-remembered.pdf

Indian City. (2018). Manitoba Music. Retrieved on April 25, 2018 from

https://www.manitobamusic.com/indiancity

Jacobs, J. (2011). The death and life of great American cities. New York, Modern Library.

Lebar, E. (Feb 6, 2018). Six Manitoba artists and acts nominated for Junos. Winnipeg Free Press. Retrieved on May 8, 2018 from https://www.winnipegfreepress.com/arts-and-life/entertainment/music/five-manitoba-artists-and-acts-nominated-for-junos-472968323.html

Maddin, G. (2016).My Winnipeg. Retrieved on November 7, 2018 from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UA0vh3SnYrU&start_radio=1&list=RDUA0vh3SnYrU&t=2

McLuhan, Marshall, Kathryn Hutchon, and Eric McLuhan. City as classroom: Understanding language and media. Agincourt, Ontario, The Book Society of Canada, 1977. Accessed 3 Nov. 2017.

Monkman, L. (2016) Indigenous designers take architecture to new level at Assiniboine Park.

CBC News Sept. 13, 2016. Retrieved on November 27, 2017 from http://www.cbc.ca/news/indigenous/indigenous-peoples-garden-assiniboine-park-1.3760514

Reynolds, N. (2004). Geographies of writing: Inhabiting places and encountering difference.

Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press.

Seal, B. (2013). Baudelaire, Benjamin and the birth of the flaneur. Psychogeographic Review. Retrieved on November 7, 2018 from http://psychogeographicreview.com/baudelaire-benjamin-and-the-birth-of-the-flaneur/

Stewart, P. R. R. (2015). Indigenous architecture through Indigenous knowledge:Dim sagalts’apkw nisim̓ [Together we will build a village].Diss. University of British Columbia, 2015. Web. Date accessed November 27, 2017.

Thiessen, B. (2018). Here’s the complete list of 2018 Juno award winners.Exclaim.Retrieved on May 8, 2018 from http://exclaim.ca/music/article/here_are_the_2018_juno_winners

Helen Lepp Friesen teaches in the Department of Rhetoric, Writing, and Communications at the University of Winnipeg. Her research interests are multimodal teaching of writing. She enjoys getting her students involved in practical writing activities such as performing writing on the university radio station and publishing a journal of student writing.

Helen Lepp Friesen teaches in the Department of Rhetoric, Writing, and Communications at the University of Winnipeg. Her research interests are multimodal teaching of writing. She enjoys getting her students involved in practical writing activities such as performing writing on the university radio station and publishing a journal of student writing.