Values and Participation: the role of culture in nature preservation and environmental education among the Baganda

CASE STUDY

Decent life depends on nature’s provision of stable resources. In this report I explore cultural efforts embedded within nature preservation and environmental education among the indigenous Baganda and how these can be emulated to inform modern environment conservation programmes. Accordingly, environmental conservation in Buganda was guided by clearly streamlined gender roles and cultural values through spirituality and the clan system which defined the ethical relationships between human culture and the environment. The key challenges towards this include gender inequality and the associated stereotypes, the political climate in the country, and modern religions. Successful mitigations should essentially hinge on integrating indigenous conservation methods in formal school curriculum as well as undertaking sensitization and empowerment campaigns geared towards nature preservation.

1.0 Introduction

Bugandais the largest kingdom in the Republicof Ugandawith 4,126,370 people (Uganda Bureau of Statistics, 2005 p12). These people are socially organized in fifty four patriarchal clans (ebika). The cultural head of the Baganda is the Kabaka (king). The Kabaka is assisted by the Bataka (chiefs) and the lukiiko (parliament) to govern his subjects (see appendix 1). The Baganda trace their biological descent through their paternal lineage. The livelihoods of ancient Baganda appreciated and worked within nature’s limits. Lubowa (2006) contends that the Baganda aimed at fair sharing of the benefits and costs of use of natural resources. There was environmental conservation among the different communities and interest groups, including both rich and poor, and between their generation and those of the future. This report presupposes that revitalization of Baganda cultural heritage in nature conservation would significantly enhance ecological sustainability.

1.1 Background

The study involved consulting opinion leaders on nature preservation methods, as well as related literature review. Besides the availability of undocumented oral tradition, the one-on-one consultations were particularly helpful in acquiring information concerning indigenous environment management methods among the Baganda. The study further explored the importance of culture in environment conservation. It was carried out on the assumption that survival of people depended on sustainable harnessing of nature and clearly streamlining gender roles and cultural values. The other assumption was that Baganda spirituality and the modern conservation initiatives represented contrasting approaches to ecological sustainability. Lastly, spirituality was part and parcel of the lifestyles of the people, interwoven in the kingdom’s socio-economic realities.

2.0 Definition of key terms

2.1 Gender

Gender refers to social constructs: behaviour, activities, responsibilities, capabilities, expectations and attributes that a particular society considers appropriate for men and women. In light of this, Njogu and Mazrui (2009) contend that the gender roles assigned to men and women today create, reinforce, and perpetuate relationships of male dominance and female subordination. Therefore, any meaningful discussion or debate on gender ought to represent aspects of equality and equity. InBugandaculture, gender roles were clearly streamlined: men were authoritative, taught leadership skills, were expected to be responsible for their families’ well-being and also took the final decisions in the home (Ekisaakaate, 2009). Women, on the other hand, were considered the bearers of indigenous culture and were care-givers, counselors, and responsible for the day-today management of the home (Graham, 1999; Ekisaakaate, 2009). These roles were generally complementary and at times mutually undertaken. Often men farmed alongside women and also shared some household tasks. Women played advisory roles in respect to kingdom affairs. On the other hand, young girls and boys underwent separate cultural grooming to equip them with relevant survival skills.

2.2 Culture and values

Culture is the knowledge and values shared by a particular society. Geertz (1973, p.44), sees culture as “a set of control mechanisms, plans, recipes, rules and instruments for the governing of behaviour.” On the other hand, values are our standards and principles for judging worth (Halstead, 1996). This notion is echoed by Shaver and Strong (1976) who reiterate that values are the criteria by which we judge things. Among the Baganda, clans play a pivotal role in the passing on of culture and tradition to the succeeding generations. Thus, the fear of letting down, not only the immediate family but the whole clan is a very important motivation encouraging the individual Baganda to respect their culture (Kyazze, 2002).

2.3 Environmental Education

Environmental education is a learning process that increases people’s knowledge and awareness about the environment and associated challenges (UNESCO, Tbilisi Declaration, 1978). For environmental education to be meaningful, it should enable people to gain an understanding of how individual actions on values and participation affect the environment. In Buganda, informal environmental education embraced awareness and sensitivity to issues of nature preservation, dissemination of knowledge in environment conservation via stories, riddles, songs, proverbs and taboos, as well as through participation in sustainable resource use and other eco-friendly activities.

3.0 The Baganda spirituality in context

The Baganda believed in a supreme God (Katonda), who was assisted by deities (Balubaale), in the propagation of spirituality and nature conservation (Matovu,1995). To them, spirituality respected nature and the needs of future generations. Hunting was regulated by Ddungu deity, who discouraged hunting of young as well as pregnant animals. Fishermen sought blessings from Mukasa before they went fishing; luck was accorded to those who caught mature fish. Women consulted Nagadya, guardian of crops and harvest, for luck in their agricultural activities. Bush burning was strictly forbidden and punishable by the deity. Even with the presence of Christianity and Islam, the Baganda continue to remain closely attached to their belief system, though somewhat loosely. In his discussion about ancestors inAfrica, John Lukwata (2003, pp. 8-9) observes that,

“…ancestors are believed to have continued influence over the living members of their immediate kinship unit. Their influence can be positive or negative depending on the conduct of the living. They are believed to be the proprietors of the land, and are responsible for promoting the fertility of beings and that of the earth and the growth of crops.”

This is also echoed by Mulambuzi (1997, pp. 75-76), who contends that many Baganda continue to believe in their ancestors even when they convert to religions of the White like Christianity; ancestors defend them from death, diseases, accidents and show interest in what they do and even make them succeed in their endeavors. Mulambuzi further reiterates that, for the Baganda, God may be there, but He is not as close to them as the ancestors, whom they can turn to whenever there is a crisis.

4.0 Culture and environment conservation among the Baganda

4.1 The indigenous education system and environment

The Ancient Baganda cosmology promoted values that supported conservation and discouraged values and ethics incompatible with sustainable ways of life (Lubowa, 2009). This oral tradition was passed on from generation to generation through strict instruction of the young by the old using stories, taboos, riddles, slogans, tales, poetry, commentaries, proverbs, sayings, and songs with the intent to teach conservation of the environment (Osei-Amakye, 1993). Njogu (2006) observes that story-telling was a woman’s genre used to interweave experiences and share these with communities. He contends that revival of story-telling and oral traditional mythology could contribute immensely in the empowerment of women. In this regard, education institutions ought to give girls and boys equal opportunities to respond to oral questions in a bid to equip them with essential skills needed to articulate their positions and interpretation of the world, without necessarily waiting for prompts from males.

4.2 Nature preservation among the Baganda

4.2.1 The role of totems in nature preservation

The totemic system of the Baganda depicts a strong ethical connection between human beings and nature. Each clan (ekika) has a totem (omuziro), which could be an animal, insect or plant, and it is forbidden to eat one’s totem, the mother’s and grandmother’s. This ethical stand thus places a responsibility on each clan member to promote ecological sustainability through protection of totems against harm and destruction. Marriage between people of the same clan is a taboo and prohibited. The reason for this is to prevent spread of hereditary diseases (such as sickle cell anemia), an aspect of preservation of life. Secondly, marrying from other clans is intended to promote harmony and togetherness among the different clans of the kingdom. The totemic system is one of the few surviving and respected cultural practices in the kingdom.

4.2.2 Agro ecology among the Baganda

InBuganda, women were the most efficient custodians of the diversity of food species in their gardens. Greater access to and control over a wide range of crops would help them provide for their families, a virtue required for preservation of biodiversity (Rea, 1995).

The Baganda practiced mixed farming where organic manure in form of plant remains, cow dung and urine, and chicken droppings was applied to gardens to improve soil fertility. Compost pits were dug for proper disposal of rubbish and refuse (Ssozi, 2007). This decomposed manure was applied to gardens to improve their fertility. Trees were planted in gardens to provide shade for the plants, to act as wind breaks, and also to demarcate people’s farmlands and homes. Using shifting cultivation, gardens where rested for a particular period so as to regain their fertility. Reviving organic agriculture would help conserve water, mitigate climate change, and ensure sustained biodiversity (IFORM, 2009).

4.2.3 The Baganda sustainable practices in resource use

There were places with special healing power that were regarded as sacred in the kingdom. These included forests, rivers, bushes and swamps. There were certain tree species that were not supposed to be cut down as well as animal species that were not supposed to be killed. For example, I grew up knowing that if one killed a lizard (omunya), he or she would not go to heaven. This was communicated in one of the popular traditional songs. Each village had a sacred groove or a small forest dedicated to ancestral spirits (misambwa). As Sozi (2007) rightly points out, these sacred forests and grooves were a source of herbs and it was an abomination to fetch firewood from them. Similarly, the kings’ houses were constructed using timber from tree species of kirundu, enzingu, ensalaganyi and namukago (Kaggwa, 2005). Therefore, it was incumbent upon chiefs to mobilize people to plant these tree species for use during construction. In a country where the cultural leaders have been rendered powerless, it would be good to empower them to champion the conservation of the earth’s vitality and diversity as was the case in the pre-independence times.

The Baganda respected the sacredness of life by showing utmost care for fellow humans, plants and animals. Mbiti (1990, p.106) underscored the importance of belief in community among traditional Africans arguing that, in an African context, the individual does not and cannot exist alone. He accordingly concluded that an individual can only say: ‘I am because we are, and since we are, therefore I am’. The Baganda believed in life after death, and so it was a requirement to plant trees at burial sites. It was believed that these trees were resting places for the departed relatives who assumed the mizimu (spiritual) form; failure to adhere to this cultural practice would annoy the mizimu, which ultimately destabilized the peace of their families. Due to the influence of ‘modernity’, this cultural practice is being ignored as people are buried under concrete graves, supposedly as a status symbol. The clearing of trees around burial sites as well as construction of concrete graves destroys the natural environment of the area, thus the need to integrate contemporary burial rites with the traditional cultural practices.

The Baganda believed in sustainable use of non-renewable resources. Blacksmiths recycled unwanted iron items into other forms in a bid to control depletion of the resource. Similarly, sustainable use of clay was observed by the Baganda. No one was ever allowed to break a clay product even after a quarrel or during war (Lubowa, 2009). However, in the event that a pot broke, the pieces would be remixed with fresh clay and reused, or they would be used for mixing an herbal medicine known as emmumbwa.

The Baganda bark cloth industry was another manifestation of sustainable resource use. Bark cloth (though scantly done now) is made from the bark of a tree Ficus natalensis, (mutuba), which belongs to the Family commonly referred to as fig trees (Serrato, et al, 2004). Due to the benefits from mutuba (wrapping the dead for burial instead of wooden coffins, provision of firewood, manure from falling old leaves, craft products such as mats, hats, bags, book covers, and also shades in banana and coffee plantations, besides clothing the people), king Ssemakokiro decreed that massive planting of mituba trees in the entire kingdom, then, should be compulsory and this became a significant landmark in nature rehabilitation and sustainability. Several harvests could be made from each tree as long as debarking was properly done. After debarking, the stem was wrapped in banana leaves to prevent it from drying up, a process known as okusabika (wrapping), which enabled re-growth of a new bark (NAFORI, 2009) (see appendix 2). So, revitalization of the bark cloth industry would rid the country of polythene and polestar materials that are causing serious environmental damage.

6.0 Challenges facing the Baganda Culture in nature conservation

6.1 Country’s political climate

Although the central government recognizes the existence of traditional leaders, the latter are prohibited from exercising administrative powers as well as commenting on any political issue (2010, Uganda Cultural Leaders Bill). Since environmental concerns have political connotations, these highly respected traditional leaders remain very far in significantly mobilizing their subjects for such. It is interesting, however, when the government announced a plan to lease some of the country’s forest reserves to private investors: leasing part of Mabira forest (the largest equatorial forest inEast Africa) for a sugar cane plantation in 2007; the Kabaka of Buganda spearheaded the campaign to avert this otherwise unpopular plan. He instead offered over 7100 hectares of his own land near this forest, but the proposal was ignored by both the central government and the private developers (Nalugo, 2007). In 2006 the Solicitor General of Uganda approved the giveaway of over 3,000 hectares of naturalBugandaforests in Kalangala district to Bidco Oil Company (Alweny, 2006). Furthermore, with the endorsement of the Cultural Leaders Bill in January 2011, the contribution of these leaders to meaningful development initiatives, such as nature protection, appears to have been rendered inadequate.

6.2 Gender inequality and stereotypes

Despite accrued environmental benefits relating gender roles, in most of ruralBugandawomen do not have property rights and may not inherit property at the death of their husbands and fathers. Even in situations where the deceased husband did not have a son, the heir will either be the deceased’s brother or the deceased’s brother’s son. Agostino (2010) contends that women are unable to mitigate and adapt to the problems caused by climate change because they have limited access to resources and services. Much asUganda’s constitution provides for equal rights to family property for husband and wife, the cultural norms together with high illiteracy levels among women renders this provision ineffective. This situation is further exacerbated by the presentation of women and girls as subordinates occupying traditional roles of child care, nursing and midwifery, cottage industry and market trading in contrast to their male counterparts, who are portrayed in glamorous senior roles. This claim is also echoed by the Human Development Report of 2007, wherein the largest percentage of poor people in Sub-Saharan Africa are women who face gender inequalities such as lack of access to land, credit and training, limited participation in decision making, and more dependence on natural resources and greater caring responsibilities. These existing gender inequalities in the kingdom make worse many of the consequences of climate change.

6.3 Modern religions (Christianity and Islam)

The spread of Christianity and Islam inBugandachanged peoples’ perception about themselves and the environment, resulting in a unification of culture. As a result of this, the identity and traditions of the Baganda have greatly changed. In my view, the belief system of the Baganda was more than just a religion: it was spirituality that affected every activity and their way of life. This was also observed by Mbiti (1990). However, this appears to be contrary to the contemporary religious outlook that considers cultural practices, such as veneration of sacred places and bark cloth manufacturing, among others, as satanic.

7.0 Conclusion

Development which is not grounded in past values becomes irrelevant for the present generations. Once this is manifested, it baffles future direction and sustainability. Thus, development policies, such as those on environment and nature preservation in Buganda, as well as elsewhere, must strive to consolidate what was good in the past to mutually interact with present ideals, if the future is to remain meaningful.

8.0 The way forward

8.1 Sensitization and empowerment

The government ofUgandais advised to reorient its attitude on roles of cultural leaders and institutions, conceiving them as partners in development because their contribution will only be meaningful if they are fully empowered in actions leading to sustainable development, such as environment conservation and climate change mitigation. Second, parents should be encouraged to learn traditional practices that show positive human qualities of environmental conservation and thereafter pass them onto children. The challenge here would be that since the young generation has been born in the computer age, their attention and appreciation of indigenous knowledge is bound to be minimal. In light of this, oral tradition could be repackaged and passed on in form of motion pictures, music, dance, drama and radio presentations that are appealing to young people.

8.2 Integrating indigenous conservation methods in formal school curriculum

There is need to integrate indigenous environment conservation methods in the school curricula across all levels. Indigenous nature and environment conservation methods should be reflected in students’ wildlife and environment clubs as well as in activities of student unions. There should be deliberate efforts directed towards integrating indigenous environment conservation methods in school course units or developing new programmes that champion indigenous environment education.

APPENDICES

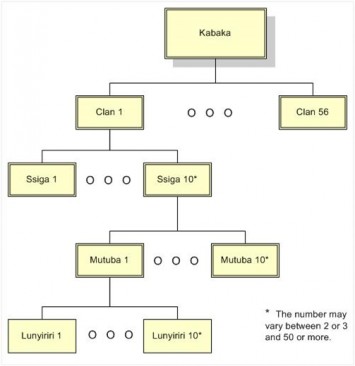

APPENDIX 1

The Ganda Ancestry

A clan (ekika) consists of a hierarchy of sub-groups, as shown in the figure below. Each is a collection of several masiga (singular, ssiga); each ssiga is a collection of mituba (singular mutuba); and each mutuba is a collection of nyiriri (singular, lunyiriri). The heads of the various groups in the clan hierarchy are called abataka (singular, omutaka).

Source: http://www.gandaancestry.com

The Baganda social fabric was knit around the clans, and sewn together by certain customs and traditions that were supposed to ensure the welfare and security of the social order (Kasozi, 2006).

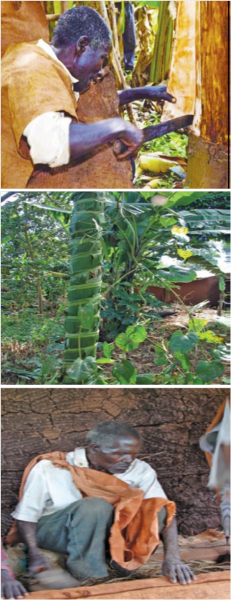

APPENDIX 2

Muganda man Making Bark Cloth

A craftsman debarks a mutuba tree for bark cloth making.

A debarked tree covered with banana leaves to allow regeneration of the bark

A craftsman making bark cloth.

Source: Uganda National Commission for UNESCO

References

Alweny, S. (2006). Solicitor General Okays Kalangala forests giveaway in The Daily Monitor. The Monitor Publications,Kampala

Agostino, A. (2010). Gender equality, climate change and education for sustainability. Beyond Access: Gender, Education and Development (24) February 2010

Dower, N. (1997) ‘Sustainable development: some ethical issues’, The Journal of Contemporary Health, 6, pp.57-60. Institute for Health,LiverpoolJohnMooresUniversity.

Geertz, C. (1973) The Interpretation of Culture: Selected Essays.New York, Basic Books.

Graham-Brown, S. (1999) ‘Marginal groups and education’, Chapter 5 in Education in the Developing World: Conflict and crisis, pp. 50-63. Longman Group UK Ltd.

Ekisaakaate (2009) Reconciling Traditonal and Modern Gender Values. CCFU,Kampala

IFORM (2009) Environmental Benefits of Organic Agriculture Positive Benefits for Society and for Nature Available: http://www.ifoam.org/growing_organic/1_arguments_for_oa/environmental_benefits/environmental_benefits_main_page.html Accessed: 20th March 2011

Halstead, J.M. (1996) Extract from ‘Values and values education in schools’, Chapter 1 in Halstead, J.M. and Taylor,M.J (eds) Values and Values in Education, pp. 5-8 and 12-14. The Falmer Press.

Kaggwa, A (2005) The Customs of Baganda. New Era Printers and Stationers,Kampala

Kasozi, A.B.K. (1981) ‘The Impact of Islam on Ganda Culture, 1844-1894’ in Journal of Religion in Africa. Vol. 12, Fasc. 2.

Lukwata, J. (2003) Integrated African Liturgy. Eldoret: AMECEA Gaba.

Matovu, K. N. (1995) ‘Environmental Conservation through Cultural practices and language use’ in Uganda: A Century of Existence. Fountain Publishers,Kampala.

Mbiti, J. (1990). African Religions and Philosophy. Second Edition.London:

Heinemann.

Mulambuzi, F. X. (1997) Beliefs in Ancestral Spirits: Interpreting Contemporary attitudes of the Ganda to the Ancestors. Unpublished MA Dissertation,University ofNatal.

Nafori Report (2009) Revitalisation of Barkcloth Making. Uganda National Commission for UNESCO. Available: http://www.unesco-uganda.ug Accessed: 28th February 2011

Nalugo, M. (2007) ‘Mabira Cutting Starts’ in The Daily Monitor. The Monitor Publications,Kampal

Njogu, K and Orchardson-Mazrui, E (2006) Gender inequality and women’s rights in the Great Lakes: Can culture contribute to women’s empowerment? UNESCO

Osei-Amakye, S. (1993) Sacred Grooves: the forgotten traditional botanical gardens in tropical Africa, pp. 53-57.Ghana: Environmental Protection Council

Phillips, A. (1999) ‘Democracy and equality’, Chapter 1 in Which Equality Matters?, pp 1-19 and 134-135, Polity Press.

Rea, V. (1995) ‘Gender: A vital issue in biodiversity’, extract from Appropriate Technology, pp. 8-9 IT publications Ltd.

Serrato, A.,Ibarra-Manriquez, G.,& Oyama, K. (2004) Biogeography and conservation of the genus Ficus (Moraceae) in Mexico

Shaver, J.P and Strong, W. (1976) Facing value decisions: Rationale-building for teachers,Belmont,CA,Wadsworth

Ssozi, K. (2007) Culture is the Foundation of a Nation. Mariah Printers and Stationers,Kampala.

Tamale, S. (2005) ‘Eroticism, Sensuality and “Women’s Secrets” among the. Baganda: A Critical Analysis‘, FeministAfrica 5: 9–36.

TbilisiDeclaration (1978), UNESCO

TheUgandacultural leaders Bill 2010

Turner, B.S. (1986) ‘Types of equality’, Chapter 2 in Equality, pp. 34-55. Ellis Horwood/Tarvistock Publication

UgandaBureau of Statistics (2005) Uganda National Housing and Population Census. Main Report

UNDP Human Development Report, 2007

Leonard Ssozi is an Administrator in the Department of Dean of Students at Uganda Martyrs University. He is currently a Commonwealth Scholar in Education for Sustainability at London South Bank University. Leonard’s research interests are in fields of cultural ecology, education for sustainability, development economics and ICT for Sustainable Development.

Leonard Ssozi is an Administrator in the Department of Dean of Students at Uganda Martyrs University. He is currently a Commonwealth Scholar in Education for Sustainability at London South Bank University. Leonard’s research interests are in fields of cultural ecology, education for sustainability, development economics and ICT for Sustainable Development.