Plastic use in wet markets: A case of place-based sustainability education in Hong Kong

Link to the JSE Winter 2023 Issue Table of Contents

Wu Chan Chan Yung JSE General March 2023 PDF

Abstract: This article provides a case study of place-based sustainability education on the use of plastic bags in a wet market in Hong Kong. We organised two field trips and engaged 20 students in conducting both quantitative and qualitative research in the wet market to examine single-use plastic consumption. Our research has found that at least 1 million plastic bag is consumed on a daily basis in all the wet markets in the city of Hong Kong. Qualitatively, we found that some of the vendors may use plastic bags as a sale strategy and to engage with customers in conversations. In contrast to the conventional schooling that promote sustainability or plastic reduction in a very abstract sense, the place-based education we attempted aims to critically rethink the concept and knowledge of sustainability in ways that also empathize with the local tradition, and remain critical of modern corporate branding, and modernization discourse. The paper ends with a discussion on reflecting plastic use in traditional wet markets in contrast with chained supermarket shifting to more plastic pre-packages.

Keywords: Plastic use, wet markets, place-based sustainability education, Hong Kong, Asia

A radical change against excessive consumption of plastic is vital to any real progress for a sustainable future. The question remains how. Mobilizing mass change in consumer behaviors has never been easy. Plastic has been ingrained into modern daily life so much that it is impossible to avoid. In view of this, some in the education sector are proposing a heuristic education approach, which is to mobilize people from within and empower them to become agents of change (Zsóka, Szerényi, Széchy & Kocsis, 2013; Boyes, Skamp & Stanisstreet, 2021; Hensley, 2017). This paper examines the potentials of place-based education in relation to sustainability to fight plastic consumption in the context of Asian wet markets. We describe how we deployed this approach to engage students in the city of Hong Kong, where over 2000 tons of plastics are sent to landfills every day, with the exact proportion of plastic bags in it unknown (Environmental Protection Department, 2021). In this paper, we document two fieldtrips in which twenty students stood by individual market vendors for more than twenty hours to count the number of plastic bags used on two normal business days. Students also conducted nine interviews with vendors and customers on their perception of giving and taking plastic bags. Lastly, we conducted de-briefing sessions with students and asked about their reflections on the processes in relation to plastic reduction. Our major findings include a quantitative count of plastic bags consumed in a Hong Kong wet market as well as qualitative inquiries into the consumption patterns of plastic bags. We will also elaborate on the effects of heuristic education approach in engaging students for a more empathetic engagement with the problem.

Heuristic Approaches in Sustainability Education

Environmental educators in Europe, US and the international eco-village movements have been developing pedagogies that focus on building capacities for actions and social transformations. Many put emphasis on engaging learners instead of spoon-feeding knowledge (Gruenewald & Smith, 2008; Somerville et al., 2011). These approaches, varying in forms and names, often motivate learners to explore on their own for knowledge and social transformation. There are for instance, experiential learning, community-based education, problem-based learning, learner-centered education, learner-driven education, and place-based education (Gruenewald, 2003; Herranen, Vesterinen & Aksela, 2018). This paper uses our case study in the wet market in Hong Kong to contribute to the current discussions on learner-driven education and place-based education.

Learner-driven education is one of the emerging approaches in the field of sustainable development education. At the moment there is no strict definition of the term. Educators would usually attribute the following qualities to it: teacher acts as a facilitator in a suitable learning environment; learners could take part in deciding what to learn; both could freely explore key concepts related to sustainability in the process (Herranen, Vesterinen & Aksela, 2018). This approach challenges the traditional settings in education as there will not be a set curriculum and course content to limit the learners. The learning itself becomes a free and self-empowering exploration of a topic. Place-based education, on the other hand, empowers learners by contextualizing the learning of sustainable development in actual life places, connecting experiences and knowledge. As David Gruenewald highlighted, place-based education is liberating in that it works against the current standardized education models which wipe away geographical and cultural diversities and alienate students from their own communities (2003a). By extending the classroom into the actual places of happenings, learners get to explore out of their own learning motives and to nurture senses of responsibilities for the communities via actual experiences. It is seen as a way to build agency for actions and change (Grenewald, 2003b; Herranen, Vesterinen & Aksela, 2018).

Learner-driven education and place-based education share the common concerns of engaging students and opening up the teaching process for explorative and iterative learning. Both aim at building capacities and agency in students for the sake of social transformations. In the case we are presenting below, which is an educational fieldtrip engaging students in a wet market in Hong Kong for studies on plastic bag usage, we adopt the framework of place-based education to open up for learners to drive their own way through for iterative learning. We will explicate the case in the following sections (Gruenewald, 2002; Haas & Nachtigal, 1998; Herranen, Vesterinen & Aksela, 2018; Smith, 2002; Theobald & Curtiss, 2000). Current studies on place-based education often focus on teachings related to ecology and environmental conservation, and most of them are based on the experiences from the Global North or international eco-village movement (Ark, Liebtag & McClennen, 2020; Smith & Sobel, 2010; Gruenewald & Smith, 2008). Studies showed that learners are more motivated in thinking about conservation if they have in their hearts a deep respect for, and connection, with nature (Gruenewald, 2003a). Students are often led to beautiful nature spaces and experience their nurturing. In contrasts, our case placed students in a Hong Kong wet market, which was dirty, smelly, and quite “bloody.” Our case will broaden the geographical and cultural spectrum of place-based education on sustainability. Can students make a connection with sustainability while counting the excessive use of plastic bags? Can they develop a better consciousness on plastic pollution? Does witnessing the scale of plastic pollution help with their motivation for plastic reduction in the future?

On top of contributing to the discussion of applying and developing a heuristic approach in sustainability, this case study also contributes to plastic reduction discussion in the context of Asia. It is no longer news that the number of plastics on planet earth has reached a critical stage. Plastic is accounting for at least 85% of the total marine wastes, causing physiological stress to marine life habitats and affecting the resilience of ecosystem. The ingestion of microplastic via seafood is also imposing threats to human health (United Nations Environment Programme, 2021). Most of the unwanted plastic – single-use plastic bags, take-away food wares, and synthetic products of the like – end up in landfills and then entered the natural environment as only 10% of discarded plastic is recycled, according to a research report about the life cycle of plastics from 1950s to 2017 (Geyer, Jambeck & Law, 2017). Although more than 60 nations are adopting bans and putting levies on the use of plastic bags or other plastic products in the past twenty years, the amount of plastic wastes continues to rise (United Nations Environment Programme, 2021).

Current discussion on plastic reduction rarely touches on cases of wet markets in the context of Asia. This paper looks into the wet market in Hong Kong where hundreds and thousands of residents do groceries on a daily basis. But instead of telling students about plastic reduction in the abstract sense, we embrace and apply Gruenewald’s notion that place-consciousness means learning to reinhabit our communities in ways that allow for more sustainable relationship. We chose the wet market because it is a unique place where the forces of “urbanization, racism, classism, sexism, environmentalism, global economics, and other political themes” intersect (Herranen, Vesterinen & Aksela, 2018; Gruenewald, 2003a). In wet markets of Hong Kong, domestic helpers from Indonesia and the Philippines, middle class grocery shoppers and vendors not only conduct grocery transaction but engage in every day conversation of cooking, child caring, inflation and other topics. At the same time, the wet market is also where meat, fish and chickens are freshly cut up and wrapped in many, often small and thinner, single use plastic bags. Hence, this research challenges our students to reflect on their “situationality” and opens discussions on the inter-relational, cultural and ecological dynamics of the ways we do groceries. It explores ways of thinking through sustainability education and plastic reductions in the Asian context where habits of grocery shopping is very different from the weekly supermarket shopping behaviors in the west. How can one think of plastic reduction in a very different cultural and historical context? Our case study shall shed light on it.

A Case in Hong Kong: Plastic Bags in Wet Market

The Hong Kong SAR government has been promoting waste recycling and reduction through setting up community recycling facilities and holding mass media campaigns for a few decades (News.gov.hk, 2013; Environmental Protection Department, 2020). In 2009, the government legislated a penalty policy on plastic bags, charging consumers fifty cents for each plastic bag they take from retailers. The policy’s impact has diminished over the years as many consumers are increasingly willing to pay for a plastic bag. Big supermarket chains often exploit grey areas in the policy by using a huge amount of plastic pre-package. The policy has also exempted the use of plastic bags for wet food product, such as fresh meat, fish, frozen food, vegetables and fruits, for reasons of food hygiene (Environmental Protection Department, 2021). Therefore, the use of plastic bags in supermarkets, wet markets and small vendors is still very common in Hong Kong after years of implementing the plastic bag levies.

Research Methodology

In 2021, we recruited a group of 20 students for field trips to a wet market in the vicinity of the university, sponsored by the Sustainable Development Goals Action Fund at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. Our research team included 20 students, of which 12 from the Faculty of Social Science, 7 from the Faculty of Arts, and 1 from the Faculty of Medicine. Most of them lived in mainland China before coming and studying a master’s degree in Hong Kong. There were a few Hong Kong local students too. Before the field trips, we prepared the students with a briefing session, introduced them to basic concepts of sustainable development, global trends in plastic reduction, as well as some background knowledge of current policies on plastic usage in Hong Kong. Each field trip lasted for 11 hours, from 8:30am to 7:30pm, covering the community’s busiest hours. At the end of each day of counting and field observation, we gathered the students for a debriefing session and a group reflection on their observations and counting results.

Our aim was threefold. First, we wanted to know the exact numerical counts of single-use plastic bag use in an average wet market on a daily basis. Secondly, we want to observe the happenings in wet market transactions when plastic bags are handed and used. What are in the minds of the shop keepers and consumers? What are the cultural habits and values in giving away and taking plastic bags? Thirdly, we want to explore a heuristic approach to plastic waste reduction education. What can we, and the students, learn from plastic users’ consumption patterns and consumers’ perspectives? Existing literature on the topic is especially lacking. Hence, this research is a pilot project aimed to explore the feasibility of the reduction of plastic bag usage in Hong Kong wet markets. By observing how people cling to plastic bags use in wet markets, we hope to contribute to more efficient plastic reduction campaign in the context of Asia.

Research site: the Shatin Wet Market

The Shatin wet market is in the central area of the Shatin district in the New Territories of Hong Kong with a population of about 688,200 (Social Welfare Department, 2021). The market was part of an urban redevelopment project in the 1980s, which replaced the outdoor wet market with an indoor two-storey building with central ventilation facilities and a waste-collection system. Today, the Shatin market is in proximity with numerous shopping malls, supermarkets, restaurants, banks, even a cinema. The Shatin market is in a huge complex managed by the Food and Environmental Hygiene Department(FEHD) of the Hong Kong Government. There are two floors in the market. The first-floor houses 125 stalls, selling vegetables and fruits, and dry goods ranging from Chinese medicines, rice and nuts to household items like towels, watches and clothes. There is even a jewelry stall. The second floor has 28 stalls, most of which sell seafood, chicken and meat, either fresh or frozen. There are two stalls selling roast chicken and pork. Every day the market is crowded with housewives, migrant domestic workers and elderlies, travelling up and down the food stall alleys for fresh buys and good bargains.

Supermarket chains pride themselves over corporate responsibility and promoting sustainability, their products often come in multiple plastic packaging even though they brand their products as natural or organic. Last but not least, this paper considers the pedagogy of place-based education in reflecting on sustainability and social justice in urban spaces. In examining the wet market space in Hong Kong, our students thought about plastic reduction not in an abstract sense but started linking it in relation to corporate supermarket dominance, class inequality and preservation of traditional market space in Hong Kong. In observing how the wet market sells fish, vegetable and meat with no pre-packaging but uses lots of single use plastic bags at the end of the transaction, which is the opposite case in the supermarket chains, students are urged to think about plastic free campaigns contextually and strategically. They also suggested innovative solution in our debriefing session. In the end, the wet market gave all of us a very special and critical kind of place consciousness. It is one that reminds us of all these intimate community bonding that is no longer seen in a corporate, cold and purely transactional supermarket setting. For the last several decades, we have been taught that the modern supermarket symbolizes modernity as it is brightly lit, air conditioned, everything in packages and hence germ-free. The modern food industry taught us to reject our traditional marketplace and called the latter dirty, smelly and unorganized. The fieldtrip therefore reminded us of the tradition of food sold without plastic pre-packaging for decades and that has been people’s wisdom of sustainability in many parts of Asia.

(Above) Shatin Wet Market in 2021. The outdoor wet market was moved into a two-storey building in late 1970s.

(Above) A stall in Shatin Wet Market selling dried products, such as eggs, nuts, and dried tofu skin.

(Above) A student counting the number of plastic bags next to a vegetable stall with a counting device.

Our first field trip took place on a Saturday, 5th June, 2021. Students were divided into four groups, with five people in each group. We placed two groups on the first floor to count the number of plastic bags handed out and observe the transactions. We put the other two groups on the second floor for fish stalls, chicken stalls and meat stalls because they handed out even more plastic bags. Members of each group used a counting tally device and they had to report the numbers every 30 minutes. The second field trip took place on 9th June, 2021, Tuesday. Half of the students were assigned to conduct interviews and take videos, while the other half kept staying around the vendor stalls to observe and to count the number of plastic bags used.

The analysis that follows will elaborate on the research findings from the quantitative counting of plastic bag used in the research period, observations in the field, interviews with stall owners and consumers, and feedback collected from students during the de-briefing sessions and feedback form.

Research findings

Our two days of field research gave us insights into the following findings. Quantitatively, we found that the number of single use plastic bag handed out in the Shatin Market is around 75000 pieces per day. If we make a logical deduction from this figure in Shatin, the number of single use plastic bag handed out in the 76 wet market complexes under FEHD in Hong Kong could add up to about 1,150,000 one day. This is a conservative estimation because we exclude supermarkets and wet markets managed outside of the FEHD system. If we take those into account, the number of single-use plastic bags consumed in Shatin or in Hong Kong as a whole will be even more.

These figures were collected by students holding counting tallies at the corners of four different types of stalls for two days, counting the plastic bags given out one by one by each stall in the wet market. We then multiply the average count by the total number of each type of stall and add together for a generic estimation of the total number in one single day. An approximate number of 6500 plastic bags was counted at fish stalls on the first day of field trips, the highest among all. Poultry stalls has given out 2300 plastic bags per day and came as the third highest figure among our findings. While it is understandable that single-use plastic bags are preferred when dealing with freshly cut fish and poultries to prevent blood and water dripping around, we are surprised to know the use of plastic bags reached the second highest number at vegetable stalls, with an approximation count of 5000 on the first day. In short, the vegetable stalls and fish stalls had the highest number of plastic bags used on both days.

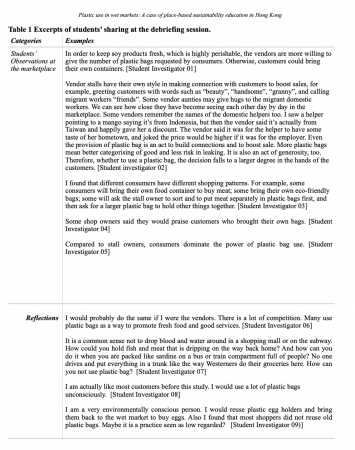

Qualitatively, we have found the following observations. First, customers in Hong Kong preferred using one plastic bag for one small item. For instance, customers will take one plastic bag for one catty of green vegetable, another bag for two tomatoes, another for some raw pork, another bag for two small fishes, and one separate bag for some roast pork in a Styrofoam box. At the end of the first field trip, the majority of the students reported feeling shocked and angry about this plastic bag consumption pattern. “There is an excessive use of plastic bags! It is so common to see a bag inside another!” one student exclaimed after sharing what he saw at a stall selling soya bean curds, where the vendor sold five pieces of bean curds each in a separate plastic bag before wrapping them all in a bigger plastic bag. “Some customers brought their own shopping bag, but they kept putting plastic bags inside!” another student echoed. “Some people brought their own shopping cart. But inside the cart, there are dozens of plastic bags.” Our students reflected this plastic bag phenomenon during the debriefing session (Table 1).

Secondly, we found that shopkeepers or staffs like to use plastic bags as part of their sales strategies. Many sellers would literally wave a fresh plastic bag in order to appeal to customers nearby. Once the customers stop and decide on the items they choose, these sellers would immediately wrap up the items in multiple bags before the customers reach for their purses. Our students have found that this could be a way to promote “good service.” One student from the anthropology department shared, “maybe the vendors want to use these plastic bags to prove that they are generous with packaging and that there is no leakage issue.” We observed this phenomenon of “plastic bags meaning good service” rather common among the vegetable vendors, especially those in the busiest alleys where several vendors competed with each other. (Table 1)

Last, we have found most of the plastic bags used for wrapping seafood, poultry, and meat could hardly be recycled. Fishmongers and butchers also like to cut up the items in front of customers to prove the food’s freshness. The result is that plastic bag used is often holding a lot of blood and animal tissues. Customers who chatted with us said they would dispose of these dirty and blood stained single-use plastic bags after use.

Analysis: Place-based Learning From Judgmental to Empathetic

The findings from this pilot study were remarkable in terms of research design and nature as there was no similar data on the topic in current literature. The number of plastic bags counted and the ways they were transacted in the Shatin wet market could potentially act as a reference for similar studies in the future. Upon observations, most of the students were appalled and wanted to urge for changes or alternatives. During the two days of debriefing sessions, we the researchers observed the following pattern: students identified the problem of excessive plastic bag use; they judged that it is not right; they wanted to find out who was responsible. Initially, many of them have suggested that consumers should take up more responsibilities in reducing plastic bag use. Yet after a few rounds of discussion, students started to put themselves into the shoes of both the customers and the shopkeepers and reflect on several structural issues (Table 1).

Some students took the chance to observe the role of the vendors and showed empathy to their situations. One of the students said, “I would probably do the same if I were the vendors. There is a lot of competition. Many use plastic bags as a way to promote fresh food and good services.” Another student shared critical reflections on the uniquely air-conditioned passageway of walking in Hong Kong. “Many families have to pass through shopping malls connected with transit terminals and travel on bus or subway home after the grocery trip. It is a common sense not to drop blood and water around in a shopping mall or on the subway. How could you hold fish and meat that is dripping on the way back home? And how can you do it when you are packed like sardine on a bus or train compartment full of people? People do not drive and do not have car trunk like the way Westerners do their groceries here. How can you not use plastic bag?” Raising these questions, students started to take into consideration of the urban design, public transit and the congested living condition of Hong Kong. One student reflected after interviewing with a customer, “some of them are actually quite conscious (environmentally). Some of them also brought containers to hold freshly cut meat and fish.”

What is most interesting is that more than half of the students showed a positive appraisal to the unique wet market space and culture in Hong Kong. Many found the hustling wet market a place full of neighbor interactions, where vendors and customers often enjoyed casual conversations. Some of the vendors also mixed familial lives with the market setting, putting their kids at the stall for homework and care. Vendors and customers also build a good relationship with each other. Students have found the wet market a well-knitted community network that is warm and treasurable, as compared to the solely commercial nature of supermarket chains.

Some vendors were also willing to share their points of view on plastic reduction policies and the current habits of plastic bag usage with us. Some, however, looked at us with suspicion and feared that we were sent from the government to fine them for violating plastic bag regulation.

Wet markets in Hong Kong are one of the common sites of plastic bag pollutions but it is also a unique place of food consumption and transactions. Does the solution lie with erasing the local traditional marketplace and replace them with supermarkets? How can we innovate on plastic solution, wet market consumption and preserving community life at the same time? After two days of fieldtrip, many students are willing to look into the complexities of the problem instead of simply blaming the plastic bag users. We could see more critical thinking in students’ reflections. Quite a few of them accepted the plastic bag users’ points of view and tried to think about solutions that acknowledge these viewpoints. We found that students’ act of reaching out to converse with customers is a major turning point. If they just stood around and counted the number of plastic bags, they may have remained judgmental and became annoyed by the counting of excessive plastic use. But once they started to do interviews with both vendors and customers, they were starting to re-consider factors related to hygiene, efficiency and the city space. Most interestingly, the majority of the students came to reflect their own consumption patterns at the end of the de-briefing. Some said, “I am actually like most customers before this study. I would use a lot of plastic bags unconsciously (Table 1).” In the end, the 2-day fieldtrip serves as a mirror in which student participants found their own image from the collective unconscious of the daily buying and selling. Many of them started to feel an urge to change and explore new ways on plastic reduction.

Plastic use in wet markets Table 1 PDF

Conclusion

This paper considers sustainability education in plastic reduction in the local Hong Kong context of a wet market. It argues that the wet market can be a great place where students reflect upon the concept of sustainability in a very critical and localized manner. Through sending students to a wet market to count the number of single use plastic bags, our research has found not only an unbearable amount of plastic use and waste on a daily basis in the city of Hong Kong, it has also motivated critical reflections among our students on the ways in which local wet market culture, plastic use and our city space are closely intertwined.

In a wet market space, there is little food packaging as most produce is fresh, stacked up and not wrapped in any plastic. There, plastic use is much less about pre-packaging but serves as a final transit process. The single use plastic bags enable working citizens to shop and commute efficiently in the Hong Kong urban space of malls and subways. Unlike in supermarket chains where almost all produce is heavily plastic wrapped or sealed, small business vendors in the wet market could at most “wave” a plastic bag to promote their produce or service quality. In this way, plastic bag use is about maintaining urban etiquette, enabling small business vendors to provide grocery services while earning a profit. Last, our students have found a lot of community connections across class and ethnicities in a wet market space. Domestic helpers from the Philippines and Indonesia, lower class janitors, middle class local housewives, and vendors mingle a lot and build a friendly community bond here beyond grocery transactions. Students also observed that some customers were increasingly aware of the plastic problems and brought along their own bags and containers to shop.

The research prompts one to reflect critically on plastic reduction campaigns and sustainability education in a non-western urban but traditional market context. How can one think about effective plastic reduction in a traditional space like the wet market where small and independent business dominate and food is sold without pre-packaging? While big corporates or supermarket chains pride themselves over corporate responsibility and promoting sustainability, their products often come in multiple plastic packaging even though they brand their products as natural or organic. Last but not least, this paper considers the pedagogy of place-based education in reflecting on sustainability and social justice in urban spaces. In examining the wet market space in Hong Kong, our students thought about plastic reduction not in an abstract sense but started linking it in relation to corporate supermarket dominance, class inequality and preservation of traditional market space in Hong Kong. In observing how the wet market sells fish, vegetable and meat with no pre-packaging but uses lots of single use plastic bags at the end of the transaction, which is the opposite case in the supermarket chains, students are urged to think about plastic free campaigns contextually and strategically. For instance, student reflected how it could be hard for ordinary people and domestic helpers living in small apartments in Hong Kong to practice drying up wet and used plastic bags. They also observed a high level of social interactions in the grocery transaction, usually absent in the chained super market setting. In the end, the wet market gave all of us a very special and critical kind of place consciousness. It is one that reminds us of all these intimate community bonding that is no longer seen in a corporate, cold and purely transactional supermarket setting. For the last several decades, we have been taught that the modern supermarket symbolizes modernity as it is brightly lit, air conditioned, everything in packages and hence germ-free. The modern food industry taught us to reject our traditional marketplace and called the latter dirty, smelly and unorganized. The fieldtrip therefore reminded us of the tradition of food sold without plastic pre-packaging for decades and that has been people’s wisdom of sustainability in many parts of Asia.

The wet market fieldtrip as a place-conscious education ultimately reminds us of a plastic -free market communities that existed before the invention of plastic. The challenge now is to think about plastic bag reduction at the final step of transporting food from market to home. So, in contrast to the conventional schooling that promote sustainability or plastic reduction in a very abstract sense, the place-based education we attempted aims to critically rethink the concept and knowledge of sustainability in ways that also empathize with the local tradition, and remain critical of modern corporate branding, and modernity imagination (Yip & Lam, 2000; Tsui, 2022). While connecting to the people and appreciating the traditional market space, we however ask our students not to be just nostalgic of the past but began to understand the modern corporate discourse of shaping our places and develop an environmental consciousness for action.

Last, our students have been instrumental in putting together an electronic Padlet platform that visualize our research finding and quantitative data of plastic bags counted for public viewing. The research later received more publicity as a local newspaper Mingpao picked up our research amidst the heated public discussion of plastic bag levies and national plastic reduction campaigns in China (Centre for Social Innovation Studies (CUHK) & Centre for Cultural Studies (CUHK), 2021; Wu et al., 2021). This pilot research will serve as a pilot for our next assignment that will train students into environmental communicators or change makers in the wet market setting, hoping to persuade both vendors and shoppers to use less single-use plastic. In our future research, we will also explore design solution so that students will come up with concrete suggestions or investigation into plastic use in grocery shopping in a highly dense, hygienic and urban Hong Kong, while also hoping to preserve the traditional wet market spaces.

References:

Ark, T.V., Liebtag, E. & McClennen, N. (2020). The power of place: authentic learning through place-based education. ASCD.

Boyes, E., Skamp, K., & Stanisstreet, M. (2008). Australian secondary students’ views about global warming: Beliefs about actions, and willingness to act. Research in Science Education, 39 (2008), 661-680. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11165-008-9098-5

Centre for Social Innovation Studies (CUHK) & Centre for Cultural Studies (CUHK). (2021). Plastic-free Hong Kong: Chapters on wet markets. https://www.csis.cuhk.edu.hk/plastic-reduction-and-sustainability/

Environmental Protection Department. (2020, March 30). Green@community. https://www.wastereduction.gov.hk/en/community/crn_intro.htm

Environmental Protection Department. (2021a). Monitoring of solid waste in Hong Kong: Waste statistics for 2020. https://www.wastereduction.gov.hk/sites/default/files/msw2020.pdf

Environmental Protection Department. (2021b, December 16). Plastic shopping bag charging scheme. https://www.epd.gov.hk/epd/english/environmentinhk/waste/pro_responsibility/env_levy.html

Gruenewald, D.A. & Smith, G.A. (2008). Place-based education in the global age. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Somerville, M., Davies, B., Power, K., Gannon, S. & Carteret, P. (2011). Place pedagogy change. Sense Publishers.

Geyer, R., Jambeck, J.R. & Law, K.L. (2017). Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made. Science Advances, 3 (No.7). https://www.science.org/doi/epdf/10.1126/sciadv.1700782

Gurenwald, D. (2002). Teaching and learning with Thoreau: Honoring critique, experimentation, wholenes, and the places where we live. Harvard Educational Review, 72(4), 515-541.

Gruenewald, D.A. (2003a). The best of both worlds: A critical pedagogy of place. Educational Researcher, 32(No.4, May), 3-12. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X032004003

Grenewald, D.A. (2003b). Foundations of place: A multidisciplinary framework for place-conscious education. American Educational Research Journal, 40 (No.3, Fall), 619-654. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312040003

Haas, T., & Nachtigal, P. (1998). Place value. Charleston, WV: ERIC Press.

Hensley, N. (2017). The future of sustainability in higher education. Journal of Sustainability Education, 13 (March). http://www.susted.com/wordpress/content/the-future-of-sustainability-in-higher-education_2017_03/

Herranen, J., Vesterinen, V.M. & Aksela, J. (2018) From learner-centered to learner-driven sustainability education. Sustainability, 10 (No.7). https://doi.org/10.3390/su10072190

Karmasin, M. & Voci, D. (2021). The role of sustainability in media and communication studies’ curricula throughout Europe. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 22 (No.8), 42-66.

News.gov.hk. (2013, February 27). LCQ19: Three-color Waste Separation Bins [Press Releases]. https://www.info.gov.hk/gia/general/201302/27/P201302270282.htm

Smith, G. (2002). Place-based education: Learning to be where we are. Phi Dela Kappan, 83, 584-594.

Smith, G.A. & Sobel, D. (2010). Place- and community-based education in school. Routledge.

Social Welfare Department. (2021). Population profile of Sha Tin district. https://www.swd.gov.hk/en/textonly/site_district/page_shatin/sub_districtpr/

Sobel, D. (1996). Beyond ecophobia: Reclaiming the heart in nature education. The Orion Society and The Myrin Institute.

United Nations Environment Programme. (2021). From pollution to solution: A global assessment of marine litter and plastic pollution. https://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/36963/POLSOL.pdf.

Theobald, P., & Curtiss, J. (2000). Communities as curricula. Forum for applied research and public policy, 15(1), 106-111.

Yip, Y.C. & Lam, O.W. (2000). A city without hawkers?. Street Corner. ( 葉蔭聰 & 林藹雲。(2000)。《沒有小販的都巿?》。街角。)

Zsóka, Á., Szerényi, Z.M., Széchy, A. & Kocsis, T. (2013). Greening due to environmental education? Environmental knowledge, attitudes, consumer behavior and everyday pro-environmental activities of Hungarian high school and university students. Journal of Cleaner Production, 48 (June), 126-138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2012.11.030

Wu, K.M., Chan, K.C., Chan, S.Y., Ho, Y.T. & Yung, K.W. (2021, November 7). What to do? Up to a million of plastic bags consumed in wet markets per day. https://news.mingpao.com/pns/%E5%89%AF%E5%88%8A/article/20211107/s00005/1636221804307/%E5%91%A8%E6%97%A5%E8%A9%B1%E9%A1%8C-%E8%B2%B7%E9%A4%B8%E8%86%A0%E8%A2%8B%E6%AF%8F%E6%97%A5%E4%B8%8A%E7%99%BE%E8%90%AC-%E9%BB%9E%E6%A8%A3%E6%B8%9B

(胡嘉明、陳敬慈、陳倩玉、何宇霆 & 翁加惠。(2021, 十一月七日)。買餸膠袋每日上百萬點樣減?。https://news.mingpao.com/pns/%E5%89%AF%E5%88%8A/article/20211107/s00005/1636221804307/%E5%91%A8%E6%97%A5%E8%A9%B1%E9%A1%8C-%E8%B2%B7%E9%A4%B8%E8%86%A0%E8%A2%8B%E6%AF%8F%E6%97%A5%E4%B8%8A%E7%99%BE%E8%90%AC-%E9%BB%9E%E6%A8%A3%E6%B8%9B )

Prof. Ka-ming Wu is Associate Professor, and Director of the Master Program in Intercultural Studies, in the Department of Cultural and Religious Studies at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. She was a visiting fellow, and now a life member, of Clare Hall, Cambridge University. Trained as a cultural anthropologist, she has taken up extensive ethnographic research to examine the cultural politics of state and society, waste, and most recently, gender and nationalism in contemporary China.

Prof. Ka-ming Wu is Associate Professor, and Director of the Master Program in Intercultural Studies, in the Department of Cultural and Religious Studies at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. She was a visiting fellow, and now a life member, of Clare Hall, Cambridge University. Trained as a cultural anthropologist, she has taken up extensive ethnographic research to examine the cultural politics of state and society, waste, and most recently, gender and nationalism in contemporary China.  Dr. Chris King-Chi Chan is a Senior Lecturer at School of Business and Management, Royal Holloway, University of London. He taught at the Chinese University of Hong Kong and City University of Hong Kong before he relocated to the UK in 2022. His research focuses on work, employment and sustainability in China and Asia. He is also an Honorary Senior Research Fellow at Global Development Institute, the University of Manchester.

Dr. Chris King-Chi Chan is a Senior Lecturer at School of Business and Management, Royal Holloway, University of London. He taught at the Chinese University of Hong Kong and City University of Hong Kong before he relocated to the UK in 2022. His research focuses on work, employment and sustainability in China and Asia. He is also an Honorary Senior Research Fellow at Global Development Institute, the University of Manchester.  Sin-yuk Chan is a research assistant at Centre for Social Innovation Studies, the Chinese University of Hong Kong. She has participated in various education projects for community organizations and schools, with interests in sustainability education and community arts.

Sin-yuk Chan is a research assistant at Centre for Social Innovation Studies, the Chinese University of Hong Kong. She has participated in various education projects for community organizations and schools, with interests in sustainability education and community arts.