Placing Local Food Systems: Farm Tours as Place-Based Sustainability Education

Table of Contents: Place and Resilience in Sustainability Education, April 2016

JohnsonEtAl 11 Issue Feb 2016 PDF Ready

Introduction

The interdisciplinary study of place is important to many fields such as sociology, cultural anthropology, environmental psychology, and, of particular relevance in this paper, geography (Lewicka, 2011). Human geographers understand place as space endowed with meaning, evoking notions of difference, connection, attachment, and emotion (Cresswell, 2004; Tuan, 1997). But as processes of modernity such as globalization, industrialization, and development have increasingly homogenized cultural and natural landscapes, place is said to be ‘thinning’ (Entriken, 1991), ‘stretched’ (Massey, 1994), or lost. This has been linked to widening rifts between social and natural worlds and the loss of meaning, attachment, connection, and community.

Such processes globally have sparked concern and alarm, as people perceive losses of unique natural and cultural landscapes as well as increasing social and environmental deterioration. One such system of homogenization and unsustainability is the industrial food system. Today’s modern agricultural system has shifted smaller scale, place-based, and diverse food systems to a global, mechanized one, distancing people from the sources of their food, disrupting communities, and obscuring awareness, understanding, and care. Yet, as consumer awareness rapidly increases and more people desire to know where their food comes from and who produced it, inclusive place-based food systems can provide reconnections amongst producers, consumers, community, and the more-than-human world.

In this paper, stemming from research in western North Carolina, we bring together literature from scholars of place, agro-food studies, education, and tourism as a framework to investigate the role of place in local food systems as well as the potential of small-scale sustainable agricultural places as important educational spaces via community-based farm tourism. After briefly reviewing and synthesizing these bodies of literature, we turn to the case of the Blue Ridge Women in Agriculture (BRWIA) High Country Farm Tour, an annual tour of working farms employing a range of sustainable practices in multiple counties in the North Carolina High Country, asking: 1. What is the role of place in small-scale sustainable farming? 2. Is community-based farm tourism fostering place-based sustainability education, and, if so, what is being learned? To address the first question, we explore the participating producers’ (farmers) philosophies, practices, motivations, and stories, informed by in-depth farmer interviews and surveys. To answer the second question, we investigate consumers’ (visitors) motivations for and impacts of participation, drawing on visitor survey data.

The data explored here reveal passionate ecologically and ethically oriented producers rooted firmly in place at multiple scales, as well as the potentially transformational impacts of their interactions with visitors via farm tours – including shifts in awareness, deepened dedication and care, intended behavioral changes, and connections to community and place. This research thus makes a strong case for community-based farm tourism as a model of place-based learning that extends from particular places to an ‘open’ (Larsen & Johnson, 2012) or global sense of place (Massey, 1994), contributing to socio-ecological resilience via consumer (re-)education and sustainable local food systems. We conclude with a call to expand conceptions of and approaches to education, suggesting farm tours and other community-based environmental tourism projects as potentially transformative avenues toward place-based education and sustainability across scales.

Literature Review

Place and Agro-Food Systems

In human geography, the prominent concept of place, a broad and abstract term, is aligned with difference, connection, attachment, and emotion (Cresswell, 2004; Tuan, 1977). Broadly, place is space endowed with meaning, understood as a “meaningful connection between humans and the world” (Harris, 2010, 360) that involves attachment to a particular location, to other humans, and to the more-than-human world. If we understand place in this way, then the loss of place equates with the loss of uniqueness, meaning, and connection (Harvey, 1996), a topic of increasing concern as globalization contributes to an increasing homogeneity or ‘placelessness.’ The restructuring of landscapes according to particular views and practices of progress, development, and modernity has sought to disconnect people from place and the particular. Such processes globally have sparked concern and resistance as people experience the loss of unique natural and cultural landscapes, as well as increasing social and environmental degradation. One such system of homogenization and centralization, wrought with issues of socio-ecological unsustainability, is industrial agriculture.

The belief in agricultural productivity via mechanization and technology, part and parcel of the tenets of our dominant social paradigm (Beus & Dunlap, 1990), defines what we call today’s conventional food system. This approach is characterized by industrialization, corporatization, mechanization, specialization, centralization, and large-scale production. The social and environmental impacts of such agriculture are numerous: dependence on fossil fuels, soil depletion, emissions of greenhouse gases, air and water pollution, social exploitation, violation of animal rights and welfare, issues of food security and sovereignty, and the decline of rural communities (Harris, 2010), among others. The food products lining grocery store shelves now come from around the world, linking distant places, humans, and more-than-humans that are unknown and obscured (Lyson 2004). Modern farming methods delink farms from communities and tie farmers to a set of technologies that yields prosperity for a few at the expense of many (Lyson, 2004). Rural communities, now characterized by fewer and larger farms of an industrial categorization, have seen a declining middle class, more hired workers, lower family incomes, and increased poverty (Lobao & Meyer, 2001). Accordingly, food production, distribution, and consumption have been linked to “the environmental, social, spiritual, and economic well-being of the community” (Feenstra, 1997, 28). Industrial agriculture shatters these links, perpetuating ‘thin’ places (Casey, 2001), community degradation, and the ‘stretching’ (Massey, 1994) of relations:

“The geography of the modern food system reveals that, as food chains become stretched further and in more complex ways across space, we experience both the physical and psychological displacement of production from consumption, and all of the other disconnections and disembedding which follow in that stead – loss of rural agricultural resilience and diversity, degradation of the environment, dislocation of community, loss of identity and place” (Feagan, 2007, 38).

Yet, as consumer awareness rises, such processes have sparked concern, resistance, and alternatives. People are increasingly becoming aware of growing socio-ecological degradation, health crises, and the undemocratic nature of global capitalist governance (Watts, Ilbery & Maye, 2005). To employ Wendell Berry’s observations:

“…more and more consumers are now becoming aware that our supposed abundance of cheap and healthful food is to a considerable extent illusory. They are beginning to see that the social, ecological, and even the economic costs of such ‘cheap food’ are, in fact, great. They are beginning to see that a system of food production that is dependent on massive applications of drugs and chemicals cannot, by definition, produce ‘pure food.’ And they are beginning to see that a kind of agriculture that involves unprecedented erosion and depletion of soil, unprecedented waste of water, and unprecedented destruction of the farm population cannot by any accommodation or sense of fantasy can be called ‘sustainable’ (30)…consumers are increasingly worried about the quality and purity of their food, and so they would like to buy from responsible growers closer to home. They would like to know where their food comes from and how it is produced. They are increasingly aware that the larger and more centralized the food economy becomes, the more vulnerable it will be to natural or economic catastrophe, to political or military disruption, and to bad agricultural practice” (Berry, 1995, 22).

Indeed, the continued rise in popularity of mainstream media coverage, books, and documentaries on agro-food issues (e.g. The Omnivore’s Dilemma; Cooked: A Natural History of Transformation; Fresh; Food Chains; Fat, Sick, and Nearly Dead; Vegucated; Food, Inc., etc.) is testament to the fact that consumers are increasingly becoming aware, demanding transparency and sustainability in the food system. In response, players in the conventional food system have made attempts to become more ‘green,’ some of which are noteworthy. Many such efforts, however, are little more than corporate greenwashing, resulting in a shallow and confusing ‘sustainable’ food landscape. Alternative food systems are thus deemed to be weaker based on their engagement with, or potential to be co-opted by, conventional food systems operating within the global neoliberal paradigm (Watts, Ilbery & Maye, 2005). Horizontal networks, a short food supply chain, and a truly alternative paradigm, on the other hand, characterize stronger alternatives.

We, like others, argue that such qualities are best embodied in local food systems. As Feagan (2007) related, “in this environment of concern, territories, regions, places and communities are evinced as spaces of resistance through which agency and local institutional efforts can manage change in ways which more closely meets their needs” (32). Lyson (2004) named this localized counter trend ‘civic agriculture,’ a term which refers to the “emergence and growth of community-based agriculture and food production that not only meet consumer demands for fresh, safe, and locally produced foods but create jobs, encourage entrepreneurship, and strengthen community identity” (1-2).

Yet even local food systems have the potential for co-optation, particularly when unreflexive, exclusive, or rooted in location rather than place – relying on definitions of ‘local’ based on food miles or state boundaries, for example, as in the case of local food campaigns increasingly prevalent in corporate giants such as Wal-Mart and Kroger. Employing only territory-based conceptions of place in our understanding of local leaves behind considerations of community, farm scale, and sustainable practices, and holds potential for “reactionary politics and nativist sentiment” (DuPuis & Goodman, 2005, 360).

If unreflexive, then, the move toward local, often framed as emancipatory and alternative, can in fact be part and parcel of neoliberal globalization. In reference to local food as a rational and quantifiable initiative, DeLind (2010) argues that “the public-at-large is not being asked to re-connect to context – to soil, to work (and labor), to history, or to place – but to self-interest and personal appetite” (279). For her, local food means engagement in “the continual creation, negotiation, and re-creation of identity, memory, and meaning” (279). She explicitly calls for integrating local food and place-based practice: “Without an emotional, a spiritual, and a physical glue to create loyalty, not to a product, but to layered sets of embodied relationships, local will have no holding power” (Delind, 2006, 126).

Thus, motivations grounded in morality, relationships, and place (Sage, 2007) are crucial to transformative alternatives. Moving toward such alternatives requires consumer (re)-education and producer-consumer reconnections in place. In this paper we explore the potential of sustainable agricultural spaces as classrooms, enhancing our understanding of the role of place in sustainable local food systems as well as the opportunity for place-based sustainability education via community-based farm tourism. We turn now to a discussion of place-based education and tourism before introducing our case study.

Place-Based Education and Environmental Tourism

Place-based curricula have appeared in many U.S. schools and classrooms over the past decade and a half (Leslie et al., 1999; Martusewicz & Edmundson, 2005; Gruenewald & Smith, 2008; Martusewicz et al., 2015). According to Sobel (2004):

“Place-based education is the process of using the local community and environment as a starting point to teach concepts in language arts, mathematics, social studies, science and other subjects across the curriculum. Emphasizing hands-on, real-world learning experience, this approach to education increases academic achievement, helps students develop stronger ties to their community, enhances students’ appreciation for the natural world, and creates a heightened commitment to serving as active, contributing citizens. Community vitality and environmental quality are improved through the active engagement of local citizens, community organizations, and environmental resources in the life of the school” (7).

Such experiences can be truly transformational for students. At the same time, contemporary trends in primary and secondary education that involve standards, test results, and teacher accountability make this arena an increasingly difficult one in which to bring about systemic change, creative and committed educators in supportive school communities notwithstanding. Even apart from the effects of the current ‘No Child Left Behind/Race to the Top’ types of educational regimes, formal educational institutions as they have developed in the Global North frequently have the function of reproducing the dominant culture and the systems and structures that maintain it (Bourdieu & Passeron, 1990). As Illich (2011 [1971]) pointed out, “School initiates…the Myth of Unending Consumption” (38), which exerts a powerful pull in the process of disconnection, especially as it regards the food system.

Therefore, while ‘education’ certainly includes the institutions of formal schooling so present in contemporary Western society and exported via hegemonic and homogenizing globalization to the rest of the world (Prakash and Esteva 1998), it must not be seen as defined in such narrow terms, not should it be limited to educational institutions or students in the traditional sense. Again, points from Illich are instructive: “Most people acquire most of their knowledge outside of school…Most learning…seems to happen casually and as a by-product of some other activity defined as work or leisure…[most learning is] the result of unhampered participation in a meaningful setting” (12-13, 39). Thus, informal spaces for education apart from the institutions of formal schooling must be created, maintained, and supported in order to make it truly transformative. We turn now to explore place-based learning via tourism.

The idea as tourism as educational, even transformational, is one that is currently gaining traction in tourism studies; beyond pleasure, self-satisfaction, and voyeurism, Di Chiro (2000) explains that “primarily western, middle-to upper-middle class tourists are seeking a real-world travel experience not simply to gawk, but to ask questions and to find answers: How did we get ourselves into this ecological conundrum, and how can we learn from the environmental knowledge of the indigenous cultures of the world in order to create solutions?” (277). Tourism then shifts from a one-dimensional consumer product to a place-based cultural activity that can raise awareness, teach, and produce progressive social change.

Many such tourism schemes center on the environment, the idea being that witnessing will lead to action, activism, and new perspectives. Thus, tourism spaces can become innovative and progressive political places, using traditionally capitalist spaces for alternative, progressive goals. Whyte (2010) labels this phenomenon as environmental tourism, defined as “any tourism practice the purpose of which is to engage directly with some aspect of a local community’s relationship to its environment” (75-76). If conscious of important elements such as consent, inclusion, and direct participation of the community, environmental tourism may hold transformational potential, moving us toward “a world in which we learn about the purpose and meaning of our life, a world that gives way to new values of ecological awareness, empathy for others, non-violence, human rights, and equality” (Reisinger, 2013).

Drawing from Mezirow’s transformational learning theory, Reisinger (2013) explain the ways in which shifts in worldviews can be emancipating and uncover new understandings “of ourselves and our self-locations; our relationships with other humans and with the natural world; our understanding of relations of power in interlocking structures of class, race and gender, our body awareness, our visions of alternative approaches to living; and our sense of possibilities for social justice and peace and personal joy” (18). This can be achieved through what Mezirow called a “disorienting dilemma,” in which assumptions or “habits of mind” are made visible, questioned, and perhaps altered. Such tourism types can include community-based, eco-, cultural, spiritual, or farm (Reisinger, 2013), among others. The remainder of this paper will explore farm tourism – which could also be considered community-based, eco-, cultural, and perhaps even spiritual tourism – in greater depth.

Farm Tours

Agritourism broadly is farm-based tourism that includes a range of activities, from food-focused cultural festivals or “u-picks” to volunteer stays (Schnell, 2011), reflecting heightened tourist demand to experience place and region (Lopez & Martin, 2006) and offering farmers an avenue for diversification (Marsden, 1986), enhancing farm income, linking farm and non-farm community members, and educating or sensitizing the public to agricultural issues in order to gain both economic and political support (Brodt et al., 2006). While research in agritourism broadly is beginning to become more prevalent in the U.S. (long popular in Europe), the unique phenomenon of community-based farm tours is understudied and holds potential for transformational place-based awareness and environmental education (Spurlock, 2009). In one of the only investigations of an annual farm tour, Spurlock (2009) argues that, for threatened communities and lifestyles in the rural US,

“food-centered advocacy tourism…figures as an act of cultural and historical remembering, of commemorating that which has been lost to development and/or economic pressures, and of re/making and complicating the relationship with body and land that are lost or devalued to the ‘progress’ narrative of neoliberal development and the destructive forces of global capital” (Spurlock, 2009, 7).

Farm tour participants, according to Spurlock’s first-hand observations, bear witness to “wounded places” as they simultaneously co-perform “in narratives of healing and sustaining” (8). Rather than writing these tours off as “little more than an opportunity for city folks to play farmer for a day or two” (8), she argues instead that this embodied experience can plant “the proverbial seeds of change” (8): “To experience this tour is to experience those values toward the land, labor, and community through shared storytelling, discussion, and sensory-based exploration and discovery that invite connection and self-reflexivity” (12).

This paper expands from such observations of a community-based farm tour to explore in-depth participating farmers’ stories and visitor motivations and impacts, asking broadly: What is the role of place in small-scale sustainable farming? Is place-based sustainability education occurring via community-based farm tourism, and, if so, what is being learned? To begin to answer these questions, we turn now to the case of the Blue Ridge Women in Agriculture High Country Farm Tour.

Case Study: The Blue Ridge Women in Agriculture High Country Farm Tour

This research centers on an innovative project of agro-food reconnection – the Blue Ridge Women in Agriculture High Country Farm Tour – in western North Carolina. The Mountain Region of North Carolina consists of 23 counties in the Appalachian Mountains, comprised most prominently by the Blue Ridge and Great Smoky Mountain subranges. The seven northernmost counties, in the Blue Ridge Mountains, are known as the High Country: Alleghany, Ashe, Avery, Mitchell, Watauga, Wilkes, and Yancey (see Figure 1). Centered around Boone, home to Appalachian State University, the area is widely known for its natural beauty and deep cultural traditions. Despite the impact of national trends of agricultural consolidation and farm loss, agriculture remains economically important; Western North Carolina houses more than 12,000 farms producing fruits, vegetables, meat and dairy products, Christmas trees, tobacco, and nursery plants (Kirby et al., 2007). Tourism is the region’s top industry, driven in large part by the scenic natural and agricultural landscapes.

But such an image obscures the deeply felt impact of modern and neoliberal reforms on the area. Many of the cultural traditions that the North Carolina Mountains conjure have in reality declined or disappeared; Owen (2007) documented a landscape transforming from largely rural to suburban as consumption replaces production and ever-encroaching development threatens the area’s natural and cultural heritage:

“Land use is … changing as construction projects now must climb out of the valley onto the fragile slopes of surrounding mountains because land on the valley floors has been developed already. Consumption has replaced production in a region that was once a multi-livelihood, agricultural-based community economy where self-reliance, reciprocity, and a rural ‘commons’ supported a relatively high-quality and stable way of life. … In the past three decades Boone, North Carolina … has changed from primarily rural and forested to a suburban landscape. This pattern is accelerating. But not only the land has changed; the mountain culture is also under assault. In the context of sustainability, paradigms of economic development are called into question as these changes intensify, altering land-use patterns and increasing levels of material consumption” (3-4).

Amidst such assaults, grassroots nonprofit organizations and activism revolving around local agro-food systems, which lie at the intersection of natural and cultural landscapes, are readily found in the area, such as the Blue Ridge Seeds of Change Initiative, the Appalachian Sustainable Agriculture Project, and, the focus of this research, Blue Ridge Women in Agriculture (BRWIA), headquartered in Boone. Offering year-round educational workshops, networking events, and grants for sustainable women farmers and their families with the goal of strengthening the High Country’s local food system, the annual High Country Farm Tour is their flagship event. The tour aims to highlight those farmers and community members who are fighting for the community economy, preservation of natural and cultural landscapes, sense of place, and sustainable agriculture.

The High Country Farm Tour is an annual two-day tour in which small-scale working farms[1] employing a range of deeply ethical and ecological practices open themselves to visitors, providing experiential and sensual tours of their farms, homes, products, and practices that bridge human and more-than-human worlds. The goals of the tour as outlined by BRWIA are to connect producers and consumers, to provide farmers with economic opportunities, and to educate the public about sustainable agriculture and local food. The hope is that embedded relationships (economic, ecological, socio-cultural) might be formed, awareness might be raised, and agricultural education might take place.

In June 2014, 20 farms in two countries, Ashe and Watauga, participated in the eighth annual BRWIA High Country Farm Tour. The farms were ‘open’ to visitors from 2-6 p.m. on Saturday, June 28, and Sunday, June 29. Visitors transported themselves to the farms by car and were free to visit as many as they could over the two-day period, though they were advised to select three or four farms a day – descriptions and details of each farm and their offerings was provided to visitors along with their passes. Weekend passes cost $25 per carload, sold by BRWIA prior to the tour at Ashe and Watauga counties’ farmers’ market, local stores, and online. They could also be purchased for $30 from BRWIA volunteers during the tour at any of the farms, or they could purchase a one-farm pass for $10. Money raised from ticket proceeds each year covers BRWIA’s cost of facilitating the tour – any additional proceeds support BRWIA programs.

While farmers had been provided with BRWIA materials offering tips on giving farm tours, each farm was predominantly free to interact with their visitors as they wished. Some farms scheduled on-the-hour tours or provided special workshops on topics such as seed saving or biodynamic agriculture, while others gave more-informal tours once a group gathered, engaging in unstructured conversations with visitors, or allowing them to explore the place on their own in the meantime. Some farms had activities particularly for children or provided special workshops on topics such as seed saving or biodynamic agriculture. Some sold produce, meat, and other products during the tour, and some provided take-home educational and marketing materials on topics such as sustainable agriculture, pastured meat and animal welfare, permaculture, or community supported agriculture (CSA) programs, for example.

Methods

From May through September 2014, the first author used a feminist and participant action research methodology in the High Country, collaborating with BRWIA to market the tour, sell weekend passes at local farmers’ markets, and collect survey data from both producers and consumers. Analysis for this paper employs data generated from in-depth farmer interviews, farmer surveys, and visitor surveys during this research period.

In-depth, semi-structured on-farm interviews were conducted with all 20 producers prior to the tour to compile farm profiles and to understand their histories, philosophies, practices, and motivations for participation in the tour. Interviews were voluntary and lasted between 30 minutes and four hours. While the interviews often veered in various directions based on the nature of conversations, pre-determined questions asked to all producers included those surrounding their farm histories, philosophies and broad motivations, agricultural practices, connection to the High Country, outlets for their products (farmers’ markets, farm stands, CSAs, local restaurants, etc.), and motivations for participating in the tour. The data generated from these interviews were analyzed thematically according to broad-topic and emergent-fine codes using NVivo. The data were used both for the purposes of this research and to inform farm-highlighting posts on the BRWIA High Country Farm Tour blog (http://farmtour.brwia.org/blog/category/2014-featured-farms).

A follow-up survey was also distributed to farmers via email the week after the tour, aimed to more broadly assess their Farm Tour motivations and goals as well as to understand individual experiences and perceived impacts of the tour, along with questions aimed to collect specific data desired by BRWIA to improve future tours. Surveys were distributed to all 20 farms, incentivized with a $50 Visa cash card, and 16 surveys were returned (80% response rate). Farmers were asked to respond to multiple choice, five-point Likert scale, mark-all-that-apply, and open-space questions. Survey data was analyzed with descriptive statistics, and open-ended data was analyzed qualitatively using broad and emergent fine codes.

Visitors also received a follow-up survey via email the week after the tour, aimed to broadly understand their motivations and impacts, along with specific information desired by BRWIA needed to improve future tours. Of the 448 visitors who attended the 2014 High Country Farm Tour, contact information was collected and recorded from 163 visitors; at least one person from each carload was asked to provide this information, and others in the group were given the option as well. Of these 163 visitors, 121 expressed willingness to complete a follow-up survey delivered by email. Of these 121 surveys distributed, 67 responses were returned, a 55% response rate. Visitors were asked to respond to multiple choice, three- or four-point Likert scale, and open-space questions pertaining to their motivations for participation, on-farm experiences, and impacts of the tour, along with questions aimed to collect specific data desired by BRWIA to improve future tours. The survey was incentivized with the chance to win one of four $50 Visa cash cards or one of four High Country Local First Rewards Cards[2]. Visitor survey data were analyzed with descriptive statistics, and open-ended data were analyzed qualitatively using broad and emergent fine codes.

This paper draws from data obtained from farmer in-depth interviews and farmer surveys, focusing particularly on themes of place and sustainability; and visitor surveys, overviewing motivations for and impacts of their participation in the tour. Relevant demographic data for both groups is also overviewed. Our findings aim to answer the above-mentioned questions: What is the role of place in small-scale sustainable farming? Can farm tourism foster place-based sustainability education, and, if so, what kinds of learning is possible?

Findings

High Country Farm Tour Farmers

Twenty farms in Ashe and Watauga counties participated in the 2014 High Country Farm Tour, nearly all (17) returning from previous years’ tours. The farmers ranged in age from early 20s to mid-70s, and while most were female-male couples, participating farmers also included single women farmers (7) or female-female couples (1), reflecting the national rise in women farmers who have been shown to espouse community-oriented, caring, and more-than-economic motivations (e.g. Jarosz, 2011, Delind & Ferguson, 1999). All but two farms were first-generation, again illustrating a growing number of female and young farmers (Trauger, 2007), and, reflecting the demographics of the region, all farmers were white. Most participating farms sold their products – including vegetables, fruits, meat and dairy products – at local farmers’ markets, CSA programs, restaurants, and cooperatives.

Participating farmers owned, rented, or worked land ranging from .5 to 157 acres and employed a variety of self-described sustainable practices, such as certified or non-certified organic, biodynamic, permaculture, mindful, ethical, natural, educational, and agro-ecological. Their practices were deeply intertwined with their philosophies and motivations, which were overwhelmingly non-economic. Rather, when asked in their interview to describe their goals and motivations for farming, themes centered on community and place, connection and relationships, care and love, awareness and consciousness, sustainability and self-sufficiency, lifestyle and culture. Similarly, nearly all of the farmers (88%) reported in the survey that their primary motivations for participation in the Farm Tour were not economic; rather, their goals centered on themes of education and awareness, support and sharing, relationships and connection, in addition to secondary economic-related goals such as visibility, exposure, and sales.

While the amount of time spent farming and living in the High Country varied, all farmers espoused a strong connection to and love of their place, which took on a variety of conceptions and scales. Many were drawn to their farms and the High Country by a love for the rural landscape, agricultural heritage, beauty, and a ‘simpler’ life. Holly and Andy of Against the Grain Farm, for example, grew up in North Carolina’s Piedmont region but were driven to re-embrace their family’s mountain agricultural heritage. After farming rented land for a few seasons, Holly and Andy were compelled to ‘put roots down’ in a place of their own:

‘We realized that…we wanted more of a long-term commitment to really invest in the soil and soil building and cover crops and compost, and we really wanted to be able to invest in a place and put roots down. And so we started looking for farms and we looked for awhile not so seriously and then pretty seriously, and we found this place and just felt right away like it was home…We feel that this is our place, and we know this is our place, and we’re not going anywhere.’

This connection to place informed Against the Grain Farm’s practices, which Holly described as organic and biodynamic agriculture – a holistic approach to farming that understands the farm as a living organism or actor:

‘It’s almost like the farm has a will in a way, and we have a will as people living on the farm, and we’re a part of the farm, we’re influenced by that will if you will, like it’s got agency. I feel like places have kind of a feel to them, they have a spirit to them in a way, whatever that is to you, to anybody, it’s just like going to your favorite place that you like to hike, you just like it because it has a certain feeling, like a connection in some way, and this farm really resonated with us. So it’s just engaging in farming with a little bit of that perspective in mind.’

David and Susie of Fog Likely Farm came to the High Country in the 1960s in part as a rejection of suburbia and development, craving instead self-sufficiency, sustainability, and a simple and beautiful life. As Susie recalled:

‘I grew up in boring suburbia in a town I couldn’t wait to get out of … I was into spinning and weaving and making pottery and you know learning old-time string band music, and I wanted to live in the mountains, I wanted to live like I was born in the late 1800s you know, on a farm. So that was my motivation, and…all I could think of was a place that was beautiful, and so I got this place, and I thought it was beautiful…And this is I think what I want to share, is that this place, even though it had nothing, it was a shell and 6/10 of an acre (at the time), it had beauty, it had soul I think. And it had a place for a garden, I could get firewood if I needed it, you know, we’re sustainable here. We’ve got oil lamps, we’ve got wood stoves, we’ve got the hoophous#e, the greenhouse, two springs, one of which over there I was cleaning out with my little grandson because he’s into Little House on the Prairie now….I think that’s why I wanted to be on the farm tour is just to kind of share that. It’s like an art exhibit…I mean I planted that apple tree right there, it was this big, and now it’s an old apple tree. And there’s just no other place that I want to be.’

While many of the participating farmers shared stories of their journey to the High Country from elsewhere, some were natives to the area. Lisa from Woodland Harvest Farm, an off-the-grid permaculture homestead farmed with her partner, Elizabeth, is originally from the North Carolina Mountains and viewed her return to the land as coming ‘full circle’:

‘I grew up in these mountains just two counties over from here, and you know the landscapes and ecosystems are the exact same as they are here, and so this is like home to me and coming home. …This has been just the absolute most healing, beautiful place to be. But so yeah I grew up in these mountains, and I went to school at Appalachian and got my undergraduate degree in planning but didn’t want to go on to be a town or county planner, and I started working for a non-profit in the area and decided to stay in the area and then went on to grad school and kept building up my education and getting degrees and learning about the environment and you know all different kinds of things about how we should be living, but it wasn’t until I moved here and started living this life that it was the full circle, full connect.’

Several of the farmers shared stories of acquiring more land over time in order to insulate and protect their place from encroaching development. Susie and David of Fog Likely Farm, for example, grew their land over the last several decades from .5 acre to 12 acres, about three of which are in certified organic production.

‘We gradually acquired more land and more land…We mostly did it with the idea of sort of protecting the place and not having other people build.’

Other farmers, such as Carol from Heritage Homestead Goat Dairy, explained that while they could bring more of their land into production, they consciously choose to use it minimally and lightly:

‘I mean this is a beautiful spot, and we could have cut all the woods, there’s five springs behind us and we could have cut all in there and made that pasture and then we would have been eligible for government funding to fence the goats…But we know that the best way is to leave it wooded over the water and it stays clear, I mean we know that. And I think again because we’re not driven by money, we just want enough to live a good life.’

Many farmers articulated connections between home, community, food, and farming, which collectively contribute to regional sustainability. As Holly from Against the Grain explained:

‘I just think it’s so important to really be connected to your food…like we as farmers are really connected to our farm and have that sense of home here, which I think is really awesome, and for communities and people to start to have that, even if it’s just a little bit, to some food that they eat I think is a really powerful thing…And I think as humans we just gather around food…we get together for potlucks, we get together for holidays, we eat you know, and when that food is not only fresh but connected to where we live…fresher, healthier, more connected, then it just makes the whole experience that much more, it adds so much to it.’

Kathleen of Waxwing Farm expressed similar ideas, situating her individual place-based contribution within a wider regional and environmental context:

‘Yeah well, the environmental aspects of it are really important to me and wanting to be a good steward of the environment, hopefully actively enriching the land that I’m living on and building my life on instead of just taking from it. Thinking about my management of my small piece of land in the larger context of the holler or my valley or whatever…it’s hard to do you know, like it’s hard to keep feeling like you’re making any sort of impact when everything around you is so not conscious of its environmental impact. But we still feel like it’s really important work, even if we’re just all maintaining these small plots and building some sort of connection regionally of environmental stewardship.’

Finally, expanding from local and regional scales, farmers also understood their work within national and global contexts, clearly drawing connections across scales. Kathleen explained that she initially became interested in agriculture through a concern for social justice, making connections between human and more-than-human systems both locally and globally:

‘My entry point to agriculture was the farm workers’ rights and farm worker justice on large industrial sized farms… people shouldn’t be subjected to these kind of conditions as workers trying to grow food for others, and you know it’s important what we eat but it’s also important that we not exploit the people that are growing for us, and you know being a small farmer is interesting also to figure out how to grow food and not be exploiting yourself or the people that are working for you. That is something that drives me is to figure out how we make that a good system…Making agriculture good for the planet and also good for people… I really would like to see vibrant local economies, and agriculture’s definitely a part of that.’

Similarly, Corey from New Life Farm was inspired to farm sustainably in part as a solution to the problems created by the industrial food system:

‘Initially I just wanted to do this so we could eat well and experience the nutritional benefits … but then I started learning about the economic, environmental, social implications of our industrial food system and that really just broadened my perspective. I kinda classify myself as a problem solver, so the way I perceive our industrial food system is as a problem, but it requires a big solution, and I knew that I single-handedly couldn’t solve this big problem, but I wanted to be a small part of it, I felt that pursuing the establishment of a small family farm that could use sustainable agriculture principles would make me feel satisfied that I was contributing to the solution to that problem.’

Lisa of Woodland Harvest Farm explained that sustainability via awareness and consciousness is what motivates them to share their farm both on the High Country Farm Tour and through year-round workshops and community events:

‘We want to share what we’re doing so that people can see that it’s not impossible to have a really low impact, to live with not a lot of money, not a lot of dollars flow in or out of the farm, and just the people that continue to learn about our footprint in this world and the resources that we consume and how maybe we can start to shift all of our collective consciousness and mindset around how we view what we need to live in this world, because you know Americans, yeah we’re consumers, and that’s how we’re bred to be, but we don’t have to be that way, so we’re out here sort of as a beacon of something completely radical and different that can be done.’

High Country Farm Tour Visitors

A total of 448 visitors attended the tour with an average of 77 visits per farm and a total of 1,540 farm visits. A total of 107 weekend passes were sold, and 64 single-farm visits were sold on-farm, making a total of 171 carloads who visited at least one farm.

Drawing on the results of our visitor survey, nearly three-quarters (72%) of visitors were North Carolina residents; of these in-state visitors, another three-quarters (73%) reported that they lived in the High Country. Other visitors’ home states included Florida (9), Tennessee (2), South Carolina (3), Virginia (2), Illinois (1), Maryland (1), and Pennsylvania (1). More than a quarter of survey respondents (33%) indicated that they have second homes in the area. Overall, nearly all visitors were from the area or visited frequently.

Nearly three-quarters (74%) of survey respondents were female, reflecting a predominantly female-driven participation pool, and nearly all respondents were white (88%). The average adult visitor age was 52, with a range from 23-75 and a median of about 50. More than three-quarters of visitor respondents indicated that there were other adults in their group, and more than a third (34%) reported that there were children (under 18) in their group, addressing the increasingly prevalent call to provide children with agricultural and environmental education. Most visitors learned about the tour at Ashe or Watauga counties farmers’ markets (41%), word of mouth (33%), a news article (30%) or signs around town (21%).

The average number of farms visited over the weekend was 3.7 farms, with a range from 1-10, a mode of 5 and a median of 3. Finally, for more than three-quarters (76%) of visitors, this was their first time participating in the Farm Tour, and the majority (79%) of visitors purchased products during the tour, such as pastured meat, honey, produce, herbs, dairy products, baked of fermented goods, lotions and salves.

Motivations for Participation

When asked to select motivations for participation in the 2014 High Country Farm Tour that best describe those of their group (see Figure 6), 70% selected ‘to learn more about local food,’ and ‘to do something fun,’ linking education and entertainment. More than half selected ‘to learn more about sustainable agriculture’ (64%) ‘to become more connected to my community (57%), and ‘to get ideas for my own garden, farm, etc.’ (55%). Additionally, nearly half (42%) selected ‘to become more familiar with the High Country, and more than a third (37%) selected ‘to see/experience scenic places.’ Space was also provided for participants to provide their own responses.

Visitors were then provided with open space to elaborate on their motivations for attending the High Country Farm Tour. Prominent themes included education and awareness, implementing or learning practices, relationships and networking, community and place. Some visitor comments related to the motivations of education and awareness included:

‘Farm tours are an excellent way to educate people about how their food is grown…(and about) the work and costs involved.’

‘Want to learn about farming and raising livestock.’

‘We are interested in learning more about sustainable agriculture and local food and what is available in the area.’

More specifically, many visitors attended the Farm Tour with the specific intention of learning sustainable agricultural practices. Some examples include:

‘We are teachers building a school garden and we are looking/were looking for additional education to build our school and personal gardens.’

‘We are starting our own small backyard farm in Florida. Raising chickens mostly. I was interested to see how some of the farms raised chickens. Just wanted to learn.’

‘… When we retire to the area, we may want to raise a few animals on our acreage.’

‘…I also hope to have my own small home-farm in the future to produce some of the food for my own household.’

“We have a farm and have an interest in sustainable living. Looking to network and get new ideas.’

And, broadening from food and agriculture, many visitors expressed a desire to know and become more connected to the High Country, experiencing places they had not seen before:

‘I wanted to know more about what we have going on in our area.’

‘We wanted to be more familiar with the community and economy of the High Country.’

‘We are very interested in the local area and it gave us an opportunity to see places we have never been, meet some of the farmers we see at the farmer’s market and learn about the history.’

‘To see places we had not seen and purchase local foods, particularly meats.’

Impacts of Participation

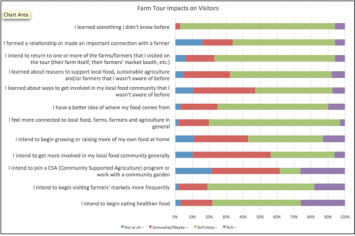

Next, visitors reported via four-point Likert scale questions (‘definitely,’ ‘somewhat/maybe,’ ‘not sure,’ or ‘not applicable’) on how their experiences on the Farm Tour impacted them, in terms of intended lifestyle changes or things they gained, learned, or experienced (see Figure 8). Nearly all of the visitors (91%) said they definitely learned something (broadly defined) they didn’t know before, and more than three-quarters (76%) said they definitely feel more connected to local food, farms, farmers, and agriculture generally. Just under three-quarters (70%) of respondents said they definitely intend to return to one or more of the farms/farmers that they visited on the tour (i.e. their booths at farmers’ markets, farm stands, CSA programs, future educational farm visits, etc.), and more than two-thirds (65%) said they definitely have a better idea of where their food comes from.

More than half of visitors said they definitely intend to begin visiting farmers’ markets more frequently (63%); that they definitely learned about reasons to support local food, sustainable agriculture, and/or farmers that they weren’t aware of before (60%); and that they definitely formed a relationship or made an important connection with a farmer (60%). Almost half of respondents said they definitely learned about ways to get involved in their local food community that they weren’t aware of before (43%), and more than a third (36%) said they definitely intend to get more involved in their local food community generally.

Finally, visitors reported via three-point Likert scale questions whether their dedication to certain aspects of the food system deepened, weakened, or stayed the same as a result of participation on the Farm Tour. More than three quarters of visitors responded that their dedication to supporting farmers economically who employ practices they support deepened (76%), and nearly three quarters indicated that their interest in learning more about/getting more involved with local, sustainable food and agriculture deepened (72%). Over two-thirds of respondents said their dedication to having relationships with the people who grow their food deepened (69%), as did their dedication to the health and well-being of the environment and of animals/non-human beings (64%). More than half of participants reported that their dedication to the health and well-being of their community deepened (57%).

When participating visitors were asked to elaborate on changes in their dedication to the local food system, their responses touched on themes of education and awareness, enthusiasm and inspiration, place and care. Some notable examples include:

‘Very impressed with the alpaca farm and the area in general. It is a different lifestyle in your area and we love it and can’t wait to retire here.’

‘Learning how the farmers have so much compassion and love with what they do for all of us!’

‘Impressed on the efforts and methods used to keep plants healthy without the use of harmful pesticides.’

‘…The farmers were so friendly and wanted to help educate their local community to inform us about the process etc.’

‘I wish that the major sources of food in grocery stores treated their land, crops and animals like the small farmers do.’

‘Seeing an abused animal with no “production value” cared for at one of the farms was touching. It made me realize that some local farmers must approach this line of work as much from their heart as from a business perspective.’

‘Honestly, if we were able to spend every summer weekend visiting our local farms (buying products from them, walking their farmland, learning something new), I would do it. I especially believe our connection to each other, our food, our community and our land would deepen and take root as would our personal well-being.’

‘By seeing the farms and the farmers, I want to be more supportive of them. Industrial farming is just too impersonal and is primarily concerned with profit.’

Finally, in the survey distributed to farmers following the Farm Tour, their experiences and perceived impacts matched those related by visitors. When reflecting on their experiences, farmers’ espoused themes of visitor awareness and education, relationships and connections, fun and enjoyment. Farmers expressed their pleasure in sharing with people what they do and why they do it, and they told of witnessing altered consumer perspectives, deepened appreciation, new relationships, and strengthened sense of community and place.

Discussion and Recommendations

The snippets of farmers’ stories explored here form a picture of love and care for place, revealing local agricultural producers and land stewards committed to beauty, simplicity, connection, community, the more-than-human world, and sustainability. Farmers articulated place-based lifestyles, deep connection to place and community, place- and care-motivated sustainable practices, linkages between place and food, regional histories, and protectiveness from encroaching development and exploitation. Their conceptions of place spanned local-to-global scales, encompassing the home, local community, region, nation, and planet.

Participant responses reflected that they had indeed engaged in a true learning process contextualized in place, resulting in both altered perspectives and intended behavioral changes. The findings presented here make clear that place and community served as an important reason to participate in the Farm Tour, intertwined with education- and entertainment-related motivations. Additionally, visitors made clear that education and awareness took place, and that relationships and connections were made, strengthening the local food system and the community simultaneously. Dedication to sustainability via place-based food systems deepened, and visitors articulated plans for behavioral changes such as more community involvement and support of local farmers, both economically and more-than-economically.

Collectively, our findings make a strong case for community-based farm tourism and other environmental tourism projects as a model of place-based sustainability education, in the context of local food systems and beyond. Place was a central element of the tour for farmers and visitors alike, both in motivations for and impacts of the tour, intertwined deeply with education, awareness, connection, and care – all vital components of sustainability. Just as farmers’ stories illustrated connection to and care for place from local to global contexts, visitors reported not only a deepened care for the health and well-being of their community, but also a deepened care for the health and well-being of the environment, animals, and more-than-human beings more generally. This suggests that connections made were not limited to the particular places experienced on the tour, nor to the High Country, but could in fact extend to an ‘open’ (Larsen & Johnson, 2012) or ‘global’ (Massey, 1994) sense of place, in which we grasp our interconnectivity and respond with care for people, places, and more-than-human beings both near and far.

Thus, the findings of this study illustrate the important role of informal agricultural and environmental education in realizing the possibilities for creating a different relationship between consumers and producers, individuals and community, and humans and more-than-humans. Such relationships contribute to place attachment and awareness of interconnection and interdependence simultaneously, disrupting assumptions and worldview that contribute to place deterioration and strengthening place ties across scales. Place-based education via community-based farm tourism and environmental tourism more broadly should thus be further investigated and undertaken by communities across the country as a vibrant pathway toward sustainability. Creative agro-food projects such as the BRWIA High Country Farm Tour warrant considerable attention as a model of place-based education, and the potential of sustainable agricultural spaces as classrooms – and place-rooted producers as teachers – should continue to be explored in greater depth.

Conclusion

Processes of modernity such as the industrial food system homogenize, disrupt, and deteriorate places globally, linked to socio-ecological unsustainability and the loss of meaning, community, connection, and attachment. Small-scale sustainable agricultural spaces, as we have shown in this paper, hold important potential for place-based learning via community-based farm tourism. More generally, environmental tourism, defined as “any tourism practice the purpose of which is to engage directly with some aspect of a local community’s relationship to its environment” (Whyte, 2010, 75-76), serves as an important educational tool, illustrating the importance of expanding how we understand and approach education in the context of sustainability.

Returning to our first question concerning the role of place in small-scale sustainable farming, our findings indicate that place is a prominent and central theme to producers engaging in this type of farming, ranging from the scale of the home or farm to that of the planet. Such overlapping and interlinked scales of place attachment set the stage for deep socio-ecological sustainability rooted in interconnection and care for near and distant others, both human and more-than-human.

Our findings related to our second question, concerning farm tourism and its potential for place-based sustainability education, indicate that such education did indeed take place on the High Country Farm Tour. Visitor surveys revealed a place-based educational process that resulted in awareness and understanding, relationships and connections, dedication and inspiration, intended behavioral changes and enhanced community engagement. Place attachments formed by visitors were tied not only to particular farming spaces and the local community, but also to human and more-than-human communities more broadly – a vital component of reflexive and emancipatory local food systems and of an ‘open’ or global sense of place, one that “can develop a consciousness of linkages and a positive integration of the global and local, building a ‘global sense of the local, a global sense of place” (Massey, 1994, 156). While recognizing this interconnection may not necessarily lead to “a world which is immediately more co-operative and benign,” it does allow us to “examine our interrelatedness” (Massey, 1994, 289) – a crucial first step in the cultural shifts needed to advance resilient communities and a more sustainable world.

The sustainable agricultural place, then, is an important transformational learning setting for adults and children alike that can teach integrated multi-scalar place attachment and convey the vital relationship between food, farming, community, and sustainability. Of relevance to both researchers and practitioners, farm tourism and environmental tourism more broadly should be advanced as an important place-based learning tool, further shifting our conceptions of and approaches to education.

Laura Johnson is a PhD Candidate in the Department of Geography at Michigan State University. Her research focuses on social and environmental justice, place, gender, feminist methodologies, and sustainable agro-food systems.

Laura Johnson is a PhD Candidate in the Department of Geography at Michigan State University. Her research focuses on social and environmental justice, place, gender, feminist methodologies, and sustainable agro-food systems.  Gary Schnakenberg works in the Department of Geography at Michigan State University. He is interested in cultural geographies of agriculture, processes of globalization, and the role of discourse in the construction of landscape and places.

Gary Schnakenberg works in the Department of Geography at Michigan State University. He is interested in cultural geographies of agriculture, processes of globalization, and the role of discourse in the construction of landscape and places.  Nicholas Perdue is a PhD Candidate in the Department of Geography at the University of Oregon. His research focuses on spatial behavior and decision-making, place-based development, and sustainability with a focus on cartography and accessible design.

Nicholas Perdue is a PhD Candidate in the Department of Geography at the University of Oregon. His research focuses on spatial behavior and decision-making, place-based development, and sustainability with a focus on cartography and accessible design.