Expanding our audience: Examining multilingual and diverse students’ responses to place-based ecocomposition to address a global threat with a global audience

Link to the JSE Winter 2023 General Issue Table of Contents

Rioux JSE General March 2023 PDF

Abstract: In her narrative, Rioux argues for the significance of teaching place-based ecocomposition to diverse and multilingual writing students in order to emphasize and demonstrate the interconnectivity between all places and spaces that we inhabit despite human-made geographic boundaries. Addressing global issues with writers who represent various places around the globe enables writing students and instructors to hone in on the international nature of climate change while emphasizing the exigence that our natural context requires. Based on primary research, the author examines how teaching place-based ecocomposition to a uniquely diverse student group affects the writing students’ recognition of the interconnectivity of all places despite geographic location. Rioux explores how diverse environmental writing students perceive the effectiveness of a place-based course as it pertains to its objectives of helping students recognize their role within our extended environments, how to become more aware of the interconnectedness that combines and connects all places, and general environmental concerns that mark the Anthropocene. Providing pedagogical insights, Rioux also shares what the students find most effective in regards to course materials, design, and overall pedagogy, as it is imperative for our collective future to understand how to engage and motivate the next generation’s thinkers, writers, and Earth-dwellers.

Keywords: Composition, ecocomposition, place-based writing, multilingual writers

Avoiding overshoot and reliance on future large-scale deployment of carbon dioxide removal (CDR) can only be achieved if global CO2 emissions start to decline well before 2030 (IPCC, 2018).

We are in a global crisis that is marked by great exigence. The changing climate and its inevitable effects cannot be denied, despite the opinions of some. In addition to clear warnings and data by leading scientists (IPCC, 2014; 2018), most individuals can recall anecdotal evidence illustrating very unusual and uncommon weather events and inexplicable changes in our climate. Violent floods and storms, severe droughts in unusual places, extreme temperature fluctuations in locations, that have maintained a relatively consistent temperature range over centuries, are oftentimes reflected in our anecdotal explorations of what is happening all around us. This reality and these sentiments demark our global and therefore our educational context: a time of great uncertainty, change, and potential destruction as we face an unknown future that we have brought on ourselves. Anthropogenic climate change is the new truth that we encounter and must take into consideration as we live, breathe, and teach. Regardless of our areas of expertise, academic fields, or disciplines, it is our responsibility and duty to keep our new context and its unprecedented exigency in mind as we educate and engage with the next generation that will tackle and meet realities that we cannot yet completely fathom or do not yet dare to.

Klahr (2012) points out:

over the course of the next few decades, every academic discipline will have to respond to the paradigm of more sustainable life practices […] As our students make their way through this emerging world, they will encounter challenges springing forth from this paradigm shift, and they will demand that every academic discipline demonstrate substantial relevance to these challenges. Indeed, any academic discipline that fails in this regard may find itself ultimately unsustainable (p. 19).

Owens (2001b) agrees, “we have a responsibility to design a pedagogical ethic informed by the need to think and act sustainably” (p. 27). Concerning college English Departments, Bruce (2011) suggests that “we must begin to teach English to show respect both for human life and for our environment” (p. 13). Writing classrooms where students from various places come together can offer an “excellent foundation for the exploration of learners’ places in an effort to understand the complexities of the organic and inorganic systems that we belong to” (Rioux, 2016b, p. 18). In times that are marked by the catastrophic effects of climate change, it is our human and pedagogical responsibility to provide opportunities and spaces for our students that encourage them to explore their role and the role of their places within our current natural contexts. The writing classroom can be a place that enables students to grapple with questions of personal relationships towards natural spheres, what personal agency means in the Anthropocene, and to explore how places are intertwined and interdependent.

Due to the dire nature of our climate crisis, we must maintain that simply keeping ecocomposition around campus is not enough. It has been proven to be beneficial and useful for a variety of academic contexts and for varying purposes like writing centers (Devet, 2011; 2014), as a tool for linguistic and etymological student explorations (Cahalan, 2008), a way to examine rhetorical situations (Moe, 2011), in order to frame research (Fleckenstein, et al. 2008), and many other instances (Balgopal & Wallace, 2009; Bruce, 2011; Dobrin & Weisser, 2002a;b; Ingram, 2001; Johnson-Sheehan, 2007; Hothem, 2009; Mauk, 2003; Owens, 2001b; Rioux, 2016 a; b; 2017; 2019; Rowland, Millner, Towne, Wohlpart 2009). However effective and enriching the mentioned examinations of ecocompositions have undoubtedly been, we must remember that our time for explorations might be running out, and keep in mind central questions that affect our students who are the next generation and the upcoming agents of change. How can we effectively teach ecocomposition to the students whose collective awareness of climate change and our extended environmental context is crucial in regards to the future of our shared home?

Facing a global challenge means envisioning and addressing a global audience, which raises even more questions: how can we teach place-based ecocomposition to individuals who do not share a common place that is integral and influential to who they are? How can we help them recognize the interdependence of all individual places despite the dissimilar geographic spaces they occupy? How can we, as ecocompositionists, help our multilingual writing students care in a way that they envision themselves as agents of change and advocates for their intertwined and interconnected individual places and view them as one?

With these questions in mind, I started to explore ways to “teach English to show respect both for human life and for our environment” (Bruce, 2011, p. 13) in a multilingual setting. I wanted to examine how I could teach ecocomposition to multilingual students who did not share a common geographic space and therefore challenged my place-based approach to teaching ecocomposition. I believe that our writing classrooms with their richly diverse components are effective places for the “construction and co-construction of globally relevant place-based writings that can set the stage for internationally-based dialogue and understanding necessary for global action” (Rioux, 2016b, p. 13). Teaching place-based ecocomposition in the described writing classrooms therefore allows students and instructors alike to break down perceived anthropogenic boundaries that disrupt our awareness of the interdependent nature of our places and the effects of global climate change on local and global spheres.

We, as compositionists, global inhabitants, writers, thinkers, and humans must seek out ways to effectively address, involve, and engage our multilingual students who might identify with different places that are geographically separated by vast distances, yet are still part of the larger web that contains us all (Cooper, 1986). In the composition classroom, all students and instructors can collectively develop a global mindset for the global threat of climate change. This must be done in order to enable writing students to symbolically combine their spaces and locations (Rioux, 2016b), recognize interconnectivity, and move forward with an awareness that we are part of a larger interdependent natural context.

It is then also paramount to understand what exactly works for our ecocomposition or environmental writing students. We need to understand what makes our writing students from various backgrounds think of themselves as part and agents of our shared natural contexts, what engages and moves them, and how we can teach ecocomposition in order to address one of our times most pressing concerns: the health of our planet (Lovelock, 2009).

Reflecting on past experiences

In my past, I have taken place-based approaches to teaching writing, especially environmental writing, in order to make the class material more personal and relatable to my students, while emphasizing the general interconnectivity that brings together all places despite geographic location. Incorporating place and its importance does not only enable students to recognize the interdependence between various physical and geographic spaces, but also the intertwined nature of symbolic spheres, such as the academic and non-academic (Mauk, 2006; Owens; Rioux, 2016b). By asking students to write about their places, we invite them to transcend perceived boundaries that define “audience” and broaden the concept to go beyond the classroom and campus. A place-based approach also allows us, as compositionists and instructors, to take into account the “spatial complexities” (Mauk, 2006, p. 214) that mark our students’ lives and therefore their writing, writing processes, and literacy practices. Place-based writing empowers the student writers.

According to my past teaching experience, teaching place-based ecocomposition in a linguistically and geographically homogenous setting was quite successful when trying to enable students to envision themselves as part of a larger ecosphere that did not only rely on each element within that sphere, but that they themselves were these essential elements who could actively engage with their places and therefore the larger environment (Rioux, 2019). By teaching ecocomposition through a place-based approach, my students were able to view themselves as agents who were responsible for their natural surroundings and who were an inevitable part of their physical spaces and vice versa.

When designing these first environmental writing courses, I selected place-based texts by local authors to ensure that my students, who were all from the local tri-state area of Iowa, Wisconsin, and Illinois, could relate to the texts, experiences, described weather patterns, local customs, and other relevant textual elements. In order to provide alternate cultural viewpoints of the same region, I decided to start the course with local Native American texts as these present the real “first place-based writers, orators, and inhabitants” (Rioux, 2019) of that particular locality that my student writers and I shared. Offering such alternate texts (Donahue, 2014; Horner et al., 2011) has been crucial to my course design as an environmental crisis requires students to develop and explore and attitude of open-mindedness and curiosity because our current way of thinking may not suffice when trying to find solutions for our present climate crisis. Following the use of local authors, I asked students to explore beyond our spaces and assigned other nature-based texts, such as Muir, Sanders, Barry, Mc Kibben, and classics like Emerson and Thoreau.

The students wrote various structured and graded assignments, free writes, journal entries, and experimented with various genres, including poetry. They discussed readings and opinions, shared their thoughts and ideas, and finally created a place-based online publication, which intended to resemble the frequently used web metaphor (Cooper, 1986), and to illustrate the interconnectivity of all individual places by being one compilation of various smaller pieces.

Overall, the course “was conducive to their collaborative co-construction and meaning-making processes of experiencing and viewing themselves within nature” (Rioux, 2019). Further, the student writers had “effectively used the semester to grapple with valuable and significant questions that, sadly, demark our current times” (Rioux, 2019). They had successfully written themselves into their environments, rhetorically written and placed themselves within a larger framework, assessed their role within their natural spaces, and re-imagined their sense of agency.

Exploring place and context

Given my successful experience with the monolingual and local class, I was motivated to challenge myself to broaden the stage to specifically address and incorporate multilingual and international students and taught the described “Writing and your place – Environmental Writing” course at a very different college. One of the most unique and enriching aspects of my new location was my students’ linguistic and geographic background. While the institution – a liberal arts seminary college in the Midwest – holds a very distinct overall population of 98% international students who represent 23 countries, my class clearly mirrored the college’s overall demographics. Out of the seven students enrolled in the course, one male student was from Benin, another male student came from Indonesia, and five, two male and three female student writers, were studying in the United States from Vietnam, but were from very different areas within their country. In other words, not a single writer shared a place! While creating the course, I felt challenged by this aspect as I had never taught a place-based ecocomposition course to such a diverse student body. My primary concern was to find ways for student writers to identify and connect with their unique and individual places while also connecting with their peers’ places and the larger environmental context that we are all part of.

Despite some differences regarding course design that I needed to implement in order to keep in mind the unique characteristics that characterized my diverse environmental writing class, using a place-based approach to incorporating and teaching ecocomposition was inevitable. Place-based approaches make central a component that is not only imperative and relevant to a current academic context or assignment, but also to one’s identity development, formation, and sense of self. In language learners or multilingual writers, place-based writing can allow student writers to stay in touch with an element associated with their first language, such as their place, and transfer this into a new setting that supports the current, local language (Rioux, 2016b). Supporting multilingual writers’ use of and reliance on “an aspect of prior linguistic affiliation and association, such as place, their attainment of fluency and multilingual identity is positively influenced” (Rioux, 2016b, p. 14) as the tensions between a first and second, or third, language and identities associated with these languages can be reduced (Harklau, 2008; Ortmeier-Hooper, 2008; Spack, 1997).

Incorporating place-based writing into a multilingual ecocomposition classroom is therefore not only effective in regards to advancing the student writers’ knowledge about crucial and important environmental realities, matters pertaining to sustainability, and personal environmental agency, but also conducive to the multilingual student writers’ continued language learning and language-based knowledge construction processes (Rioux, 2016b).

Clearly, I was unable to accommodate my students with texts that reflected their linguistic backgrounds, as I am only fluent in German and English. Compared to my previous experience with a relatively homogenous class, I was also unaware of the specific details of my current student writers’ selected places and could not directly incorporate these into our course. So, I taught it from a different angle.

Compared to my previous classes where I had to implement alternate texts in order to counter what students might be familiar with and to broaden their environmental horizons, all local and US-based texts already presented these counter-texts in my multilingual class because the student writers were accustomed to texts that reflected their localities, not our currently shared place in this country. In order to incorporate the highly important aspects of counter-texts, I assigned various place-based, theoretical, and scientific readings from US and Native American authors. Most of these writings focused on the larger issue of sustainability, climate change, and issues related to these. Also, we oftentimes spent time at the beginning of each class viewing YouTube clips of certain areas that student writers had read about for the given class, so students could gain a better image of what they had encountered in their readings. In addition, I assigned “Laudato Si”, which I had not done before, as the class was comprised of missionaries, priests, and lay persons, whose interest in the mentioned text was inevitable and the text therefore relevant in the given place.

Regarding the class writing assignments, I asked the student writers to incorporate pictures into their first narrative writing, which I had not asked of student writers before teaching at my current location. I did this to gain a better idea of my students writers’ places and to emphasize the mutual learning experience that was taking place. Prior to seeing images that students provided in their writings, I was unfamiliar with various places that they wrote about, so this approach enabled us to connect, compare, and discuss the variety that existed in our current web of students and locations.

Similar to previous courses, I emphasized place-based free-writing opportunities that took place on some Fridays throughout that semester. These non-graded assignments enabled students to explore the surroundings on and around campus and write themselves into their local spaces. While these prompts were oftentimes viewed as “weird” or “strange” due to their unconventional nature, they were eventually mentioned as being one of the most effective and favorite aspects of the class. These unusual writing activities were also a hit with my previous monolingual and monogeographical writing students! A particular writing prompt asked students to locate a spot on campus and describe their immediate surroundings while focusing on sensual experiences. Another popular prompt (an all-time “weird” favorite!!!) asked students to write a letter to a tree that they found appealing.

Eventually, at the end of our shared course, the student writers composed and compiled an online publication that incorporated all individually selected places. This publication resembled the interconnectedness of all places, and student writers explored this aspect by creating effective transition statements or paragraphs that linked each place-based writing to another. This online publication also resembled an important aspect of ecocomposition as it symbolically acted as vehicle to eliminate boundaries that separated spaces and spheres. While most in-class writing activities and graded papers were geared towards the specific class and instructor audience, the online publication empowered students to transcend the commonly perceived boundaries that separate the academic from the non-academic spheres (Rioux, 2019). An online publication in any, multilingual or not, classroom can aid students to perceive an audience shift and go “from viewing only the class as readers to understanding that their work is accessible to other potential readers outside the classroom” (Rioux, 2016b, p. 17). This concept of fluently transferring between spheres, as all spheres are inherently intertwined and interdependent, reflects a crucial concept of ecocomposition and the recognition of this is an important characteristic of successfully moving students to recognize their places and their own interdependence.

Gathering insights into my writers’ perceptions of the course’s effectiveness

Was the course effective? Did it address my questions of how to effectively teach ecocomposition to students who did not share a common place? Had I been able to expand my writing students minds in a manner that allowed them to now view themselves as agents of change, who were integrally interconnected with their environmental surroundings, no matter where these were located or if these changed? Did my multilingual and international student writers view nature as a crucial element of who they were, and would this enable them to act for nature and against climate change?

Three questionnaires

In order to address my questions and assess the continued effectiveness of the course, I handed out three questionnaires throughout the semester. The first one after our first place-based narrative in September, the second one around midterms in October, and the last one during finals week in December. While the first three questions – What is your overall impression of the course thus far?; What part of the course of the course do you find most effective? and What do you find least effective about this course? – remained the same throughout the semester, the rest of the questions varied between the first and third questionnaire as they became more specific and reflective of the progressing course. The number of questions also increased from six to nine questions.

The following analysis section outlines the students’ general perceptions of the course and the course’s overall effectiveness in relation to the outlined objectives. I include the questionnaire number in my analysis in order to demonstrate a progression or development and change in responses.

Data Results – “Nature Becomes part of my life”

When asked about the overall effectiveness of the course, how or if it enabled students to learn about the environment, how humans relate to nature, if the students perceived themselves as having agency or a responsibility towards their natural spheres, and how or if the course was enabling writers to recognize new things about their personal places, and how these related to the larger environmental context, the answers were remarkably positive.

Student writers clearly recognized that they were and are an integral and inextricable part of their natural environments, places, and other beings. Further, their sense of connecting with their personal spaces and locations led them to wanting to protect their places and those shared and inhabited by others. A male Vietnamese student writer described that “the class helps me to put my ideas of protecting [the] environment into my writings, which is the thing I did not have change [chance] to did [sic] it before. This is a wonderful class” (questionnaire 1). A male writer form Benin explained that “I understand how important it is to consider myself as part of the nature […] This class is helping me to really see my selected place as real part of me. Now, I am thinking how to protect this place” (questionnaire 1). Commenting on her expanded viewpoint that developed through the class, another Vietnamese writer described, “not only a percific [specific] place that I am at but this class enlarge [sic] my viewpoints to the worldwide ecosystem. What damages in a small place can effect and damage the whole thing” (questionnaire 1). Similarly, a male writer from Indonesia echoed, “the course helped me changed [sic] myself […] the class help [sic] me open my eyes to see nature as part of my life, and I may not destroy it. Destroy [sic] nature means destroy [sic] my own life […] I can see myself is [as] only a tiny single person out of so huge number of creatures that really depend their life on one planet. I must take care of this planet for the life of so huge number of living creatures” (questionnaire 3). Further, this student writer explained that “this class has help [sic] me love nature more and more […] I have to admit that I did not put much attention to nature. Now, I promise that I will put in practice all the knowledge now: planting bamboos and other trees” (questionnaire 2).

Also examining his own emotions towards nature, this male Vietnamese student asserted “it [the course] helps me to get closer to nature that I did not really realise. Nature is basically part of my life […] nature is also taking care of the life of human being [sic]. In turn, human being must take care of nature”. Sensing the interconnectivity that exists between all spaces, places, and beings, a male Beninese writer reflected, “I learned from this course how I am connected to all elements of the environment” (questionnaire 2).

Regarding student writer agency towards their natural spaces, the term “protector” was used 13 times, and the verb “protect” used in relation to the environment was used 27 times. Reflecting on his status as protector, a male student from Vietnam mentioned that “I am as a protector of the environment and it is my provider” (questionnaire 1), and a writer from Benin explained that “I see myself as the protector of the nature. Because it is humans who destroy everything in nature. So we should be the one to protect the environment” (questionnaire 2). Another male writer from Vietnam wrote that “if I don’t protect nature, I will most likely be affected by it” (questionnaire 3).

The importance of taking responsibility, acting for the environment, and recognizing personal agency were also central aspects that occurred throughout the course and were reflected in the questionnaires. A male writer from Vietnam explained that “I see how important is the act of protecting the nature” (questionnaire 1), and a female student from Vietnam echoed these ideas, “this course helps me to take responsibility to protect the environment by living a simple life, reduce unnecessary stuff, save electricity and water” (questionnaire 2). Incorporating the need to address the environment’s plight with others, this female writer from Vietnam exclaimed, “I am more responsible to the nature and have the obligation to raise awareness for others to appreciate the earth” (questionnaire 3), which resonates with the overall student writers’ understanding of interconnectedness, and environmental and social cohesion.

An awareness of the interdependent nature between the past, current, and future generations and the intergenerational responsibility we all hold when it comes to protecting our environment and the predictions for climate change, two students mentioned the need to think about the future generations when dealing with current environmental ideas and approaches. A female writer from Vietnam reflected that “yes, this course expand [sic] my view and envisions my mind to the important presence of nature. This course gets me involved to be part of nature and be protector of the environment for next generations” (questionnaire 1). And a male Indonesian student explained that “I must take care of this planet for the life of so huge number of living creatures; for the billions people coming after me” (questionnaire 3).

Further, students explained how they were motivated by the actions of others, such as Greta Thunberg, or authors we read in class. A male writer from Benin, for example, explained that “I learn that people are working to protect nature. I understand how important it is to consider myself as part of the nature” (questionnaire 1). A female Vietnamese writer expressed “Their [activists; authors] love is a motivation, a lesson for me to practice in my life” (questionnaire 1).

Pedagogical Implications – “By writing, I felt engaged in the process of saving nature”

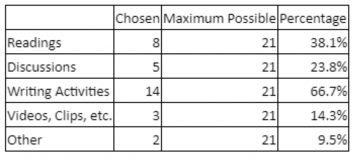

The following presents an overall collection of data taken from three questionnaires that was distributed to all seven students. For this section of the given questionnaires, I asked students to circle one or more of the following choices: Readings, Discussions, Writings Activities, Videos, Clips, Etc., and “Other”, to demonstrate which course elements they had found to be most effective in their learning experience. As there was no limit to how many items the student writers could circle, one questionnaire could have up to five circled items per student.

Readings – “my mind is more opened when I read”

The reading option was circled eight times total. Throughout, students highlighted three particularly impressive and useful texts that they considered to have been the most effective learning tool: Sustainability- A Bedford Spotlight Reader (Weisser, 2019); Laudato Si (Pope Francis, 2016), Wildbranch: An Anthology of Nature, Environmental, and Place-based Writing (Caplow & Cohen, 2015), Saving Place (Dobrin & Weisser, 2005).

In their overall answers throughout the distributed questionnaires, one female student writer from Vietnam explained: “By reading the assignment text, I can learn and realize how people love the environment” (questionnaire 1). Also from Vietnam, this female student noted, “since I read more, I explore more about the environment which is wonderful. Hence, it raises my awareness of protecting my place and other places” (questionnaire 2). A further female student from Vietnam mentioned, “I know more about [the] world based on readings. Readings give me new looks and new thinking about why and how we protect the earth” (questionnaire 1). Reflecting on the benefits she received from reading the given texts, a writer from Vietnam explained “the more I read the books, the more my mind opens” (questionnaire 3), which was echoed by her Vietnamese peer who mentioned, “the more I read essay about nature, I am curious more and want to know about environment. I am more and more aware about joining hands to protect the environment” (Female questionnaire 1). At last, another comment by a female student writer from Vietnam expressed that, “by reading and researching, I can know more about some issues that we have to face” (questionnaire 2).

Some students found the reading helpful as it allowed them to think more critically about their own writing and enabled them to use the texts as examples for what they wanted to achieve in their own essays. A writer from Indonesia explained that “the readings help me to think critically and direct me how to write” (questionnaire 1). Another woman from Vietnam pointed out, “my mind is more opened when I read assignment readings. I get more ideas that help me do good in my narrative essay. There are a lot of new things to talk about place that I might chose [sic]. These things I never thought [of] before” (questionnaire 1).

A few students explicitly mentioned specific texts that they found useful. A male Vietnamese student explained that Wildbranch: An Anthology of Nature, Environmental, and Place-Based Writing (Caplow & Cohen, 2015) and Sustainability – A Bedford Spotlight Reader (Weisser, 2019) were his favorites because, “the readings are easier to read and understand. They also give a clear reason for why the environment should be protected” (questionnaire 3). Another student writer, also from Vietnam, pointed out that Saving Place (2005) had been his favorite throughout the semester as “it [Saving Place] shows me how the people here write that different from my country. And I also learn from these readings as well” (questionnaire 1).

At last, a writer from Vietnam stated that reading and talking about Laudato Si (2015) was the most enriching and helpful assignment to her and mentioned, “I had a chance to read Laudato Si. I was attractive [sic] by this article” (questionnaire 2).

On a more critical note, a male writer from Vietnam stated, “the reading assignments are somehow make me difficult to understand it. The language is a little bit hard because English is my second language” (questionnaire 2). Explaining what aspects of the course were least beneficial, a male student from Benin mentioned “Some readings. Because they were so long or difficult to understand” (questionnaire 2), which is crucial feedback for my future course design!

Overall, students circled “Reading” as they found the texts beneficial when gaining a better understanding of the culture and cultural literacy practices and conventions, but also for content knowledge acquisition purposes.

Discussions – “this is the best way to see how each person understands differently”

Without mentioning specific instances or examples, “Class discussions” was mentioned five times as being the most effective part of the class. Commenting on the importance of class discussions and learning, one male Vietnamese student wrote that “this is the best way to see how each person understands differently and to know what we can learn more information from others” (questionnaire 2). Similarly, a male student from Benin mentioned that “we share our knowledge and I can have a new perspective to see my environment” (questionnaire2). This also suggests the importance of collaboration and dialogic approaches to the complexities of place, sustainability, and climate change. Another student described, “It [discussions] helps me get better understanding by listening to the professor and classmates and asking when I do not know or unsure” (Male Indonesia, questionnaire 1), which was seconded by his peer from Benin, who exclaimed “from our class discussions, I learned a lot from my classmates and teacher” (questionnaire 3).

These insights clearly shed light on the interconnected and mutual learning space that had evolved throughout the semester and how the students were continuously involved in actively co-constructing and negotiating meaning (Rioux, 2016b; 2019).

Writing Activities – “I want to give my voice to speak up protecting citizens’ lives”

Writing was mentioned most frequently as being the most effective part of the course in regards to its objectives of connecting students to their places, the environment, and making them aware of the interdependence of all things, and the fragile state of our current Earth. Students circled “writing” 14 times throughout the three given questionnaires, and explicitly mentioned our shared “Friday Free Writes” five times.

These “Friday Free-Writes” refer to outdoor writing activities, which occurred four times that semester. While I usually incorporate free-writes at the beginning of each Composition class, I decided to do something a bit different with this class as we only shared three 50-minute class sessions per week, compared to my usual 75-minute Composition classes. I also wanted to include a more “intense” place-based writing, thinking, and reflecting experience that enabled my students to gain hands-on insights into the acts of perceiving a place while writing about it. In addition, I wanted to build on similar writing situations and activities I had given to previous ecocomposition classes (Rioux, 2019), as these have always gained bewilderment and eventual excitement and enjoyment among student writers. So, the “Friday Free-Writes” were born in my multilingual environmental writing course! A very popular one was “Letter to a Tree”, where I asked students to wander around campus, locate a tree, and write a letter directly to it! Another was a descriptive piece that enabled student writers to find a spot on campus that resonated with them. Then the writers were asked to use specific visual and sensual details to describe their experiences from this specific natural spot. A third free-write asked student writers to take a silent walk around campus to focus on their movements, motions, and overall perceptions of themselves within a given natural space. Of course, the common initial reactions are and were perplexity and hesitance! However, once students started writing and experiencing these “weird” assignments that seemed very non-academic to them, they expressed great love for these types of writings and asked to do them more frequently, which we did!

The other relevant, graded writing assignments were a place-based narrative with images where I asked students to outline and describe the place that they identified with, that was the most influential and meaningful location to them, and that they found most crucial to their development and sense of self. I asked them to add images in order to more specifically take into account their audience who might be completely unfamiliar with the given location. This rhetorical element also aided in my student writers’ immediate awareness of interconnected texts, places, language, readers, and writers, which is a crucial aspect of ecocomposition (Cooper, 1986; Dobrin, 2001, 2011; Owens 2001a; 2001b).

Their second graded assignment, a place-based research paper, built onto the first paper and asked the writers to research a pertinent and current environmental issue that affects their selected place that they described in their narrative. The objective of this assignment was to bring students closer to the realities that mark their selected locations and that might go beyond what they personally associated with their places. This paper allowed the students to take a step back and examine their locations from a more critical perspective to see how others viewed their place and how their selected environmental issue had come to be. Oftentimes students wrote about water pollution, deforestation, or lingering issues with Agent Blue and Agent Orange, and how these still affected their selected locations today.

The last graded assignment was a place-based argumentative essay in which writers could use anything we had covered in class (readings, writings, videos, discussions, handouts, etc.) to argue why we need to protect the environment or not (no one argued “not”). This enabled the students to place their individual locations amidst other student places as they were asked to not only create this argument for their own spaces, but for our larger, extended, and shared environmental context. The three graded assignments were also important in regards to my student writers’ rhetorical placement because creating personal connections to a place via writing helps students to “realize that their individual identities are part and result of the given place and that they, by their existence and actions, also influence their places” (Rioux, 2016b).

At last, the final was an accumulation of everything the students had written. In fact, I asked them to add only what was necessary to bridge textual gaps, clarify matters, or respond to feedback they had received on already-graded essays. Now the students combined everything they knew about their places: what it meant to them, how environmental factors or others negatively affected this place to cause environmental issues and threats, and a strong argument that outlined why their place and the places of others were deserving of protection. Following the completion of their personal writing, I asked my student writers to combine all of the finals by sequencing them logically by issues, geographic places and proximity, or anything else that they found effective. They then composed transitions between student final writings to establish one large piece of collective writing which we published online via JooMag.com. Creating increased audience awareness by publishing work online enables student writers to further recognize the malleable and socially constructed nature of human-made binaries and boundaries, including the academic versus the non-academic, my place versus your place, and here versus there (Rioux, 2019; Rioux, 2016b).

As a “method of enquiry” (Park, 2013, p. 338), writing can give students a way to grapple with relevant topics while reflecting on their personal thoughts, feelings, emotions, points of confusion or interest, and ways of self-expression (Park, 2013; Ivanic, 1998). In the mentioned class, writing became an incredibly important component of recognizing personal attitudes towards nature, connectedness to personal spaces and places, and the eventual recognition of a personal belonging to a larger, intertwined and interconnected environment and system.

A male student writer from Benin mentioned that “by writing, I notice that all my emotion [sic] and feelings about nature come out” (questionnaire 1). A female Vietnamese student writer explained, “It [writing] give [sic] me the inspiration to write and gets me intuned [sic] with the environment” (questionnaire 1), and another female writer from Vietnam explained that “yes, writing activities enable me to grow in understanding more about the nature” (questionnaire 3).

A third female student writer from Vietnam agreed with her peers and stated, “through activities writing outside, I pay attention on environment surrounding me” (questionnaire 1); a sentiment, which was mirrored by a male writing student from Vietnam: “it [writing] helps me to truly connect to nature, to submerge in it. I have more sense of how to write in my paper. It contributes to my writing skill as well” (questionnaire 1).

Clearly connecting writing as a craft and writing as a mode of inquiry that leads to greater understanding of a topic, a female student from Vietnam described that writing in class helped her because “I develop [sic] environmental vocabulary, writing styles, citation styles on place-based context which is realistic and practical” (questionnaire, 2). Explaining how he could use our course material in the future, the male student writer from Indonesia described that “based on the reading I put in writing. This helps me to remember and later on put in practice: plant bamboo at my school and encourage people to plant”. He further explained that “By writing I share my understanding with others, and I learn to express my knowledge in written language” (questionnaire 2).

Gaining insight into their personal place via writing and research this individual stated, “through [the] research paper, I discovered some things happened in my country that I has [sic] not focused in [sic] before it also raises my awareness of the changing environment in my country”. They further explained that writing was an empowering, voice-giving experience: “yes, after I did research paper about environment in my hometown I want to give my voice to speak up protecting citizens’ lives” (unknown, questionnaire 2). Here, writing is associated with activism and agency, which resonated with the course’s overall objectives.

A male writing student explained that “I made a lot of research that helps me to know more about the environmental issues in my own country [Benin]” (questionnaire 2). Expanding his place-based orientation, the same student writer later on mentioned that “by writing, I felt engaged in the process of saving nature”, and that “by writing I have a long process to think about environmental issues” (questionnaire 3). This progression and expansion of his personal perception of self, place, and the world reflects what is so very crucial, integral, and unique in an ecocomposition classroom. It also demonstrates how the writing process “allows writers to connect prior conceptions to new conceptions” (Balgopal & Wallace, 2009, pg. 17).

Mirroring this reflective process, a male writer from Indonesia remarked that “the writing helped me to see my mistakes in the past and I have a promise to keep nature away from pollution” (questionnaire 3). Clearly expressing and commenting on the highly reflective nature of writing, the same student revealed “when I wrote, I actually wrote to myself and reminded myself to take care of the nature; I wrote about my mistakes in taking care of nature”.

At last one male student from Vietnam commented on our collective online publication and admitted that “[it] takes lots of efforts to do it, but it is worthy because I also learn a lot from it” (questionnaire 3).

Videos, clips, etc. – “it helps me to think about my responsibility and action for the planet”

The “Videos, Clips, etc.” category was only circled three times throughout the three questionnaires given that semester. In the first questionnaire, one male Indonesian student writer mentioned that “when I watched one of the videos, I got more insight how to start writing” (questionnaire 1). Also in the first questionnaire, a female Vietnamese student explained that “I prefer to watch to read, thus those ways can delivery [sic] the information effectively” (questionnaire 1). In the third questionnaire, a male Indonesian student remarked “I could see the real examples of mistakes done by humankinds and the real situation going on nature”. Another student writer remarked, “by watching video clip of young girl [Greta Thunberg] who willing to stand and speak out, it helps me to think about my responsibility and action for the planet” (questionnaire 2).

Having taught multilingual students for some years and having personal experience with English being my second language, I try to incorporate videos in order to enhance my lectures and overall classes. I assume that by giving students various channels of information, the likelihood of their recognizing and comprehending relevant key concepts increases. I also assume that my way of explaining or speaking of something might not work for certain students, and that by providing videos with other professionals explaining the same concept, perhaps my students can connect with that speaker if I failed in my delivery. So, I offered my students videos of individuals explaining their own nature writing and the process thereof. I also offered them a video that presented a narrated version of Henry David Thoreau’s “Where I Lived And What I Lived For”, as this text is not only fairly long, but also rather challenging for any college reader. I hoped that by listening to the words in addition to reading them, my students could develop a stronger connection to the text. We also watched a few documentaries, such as Before the Flood (2016) and BBC The World in 2050, which highlighted relevant environmental issues surrounding climate change.

Other

The “Other” category yielded two circles by student writers who found things that I had not offered as an option for having been most effective course elements in regards to the course material, course objectives, and the students’ personal learning and writing experience.

A writer from Indonesia expressed that the peer-review sessions had been most beneficial for his class experience. He noted “consultation is one of the ways I use to improve my writing skill” (questionnaire1). We had regular peer-review and tutoring sessions prior to each graded assignment, which enabled the students to focus on their writing development as well as their knowledge of their and their peers’ places, the environment, and our extended global concerns and issues. One of the students from Vietnam offered that “doing research” had been one of the most beneficial aspects of the course. She stated that, “when I spent time in doing researches [sic], I felt that it is very hard. However, after that, the information that I had is helping me a lot” (questionnaire 3).

Discussion and Conclusion

Designing and teaching this place-based ecocomposition class to my geographically and linguistically diverse student writers was a successful experience for the learners and myself. The students did not only demonstrate that they recognized their own place-based identities, the importance of their self-selected place in regards to themselves and others, and the significance of their peers’ places in their own and our collective lives, but also the overall interconnected nature of all systems, or web, that we are all part of. In addition, the student writers were able to view themselves as having responsibility and personal agency in regards to the future of their individual places, the places that their peers identified with, and therefore our global and collective future as we face climate change together.

In addition, the student writers revealed what they found most effective when trying to connect to their personal and our collective places, and how they established a sense of agency throughout the course. These student insights provide us with valuable data that we can apply to our personal pedagogical approaches to teaching place-based ecocomposition to multilingual and multi-geographic students who do not share geographic locations or identify with spaces that might not appear similar at first sight.

In regard to my original renditions of the mentioned class (Rioux, 2019), which I designed for a linguistically and geographically homogenous group of students, the current course was impactful in some aspects of my current and future idea of what is integral to course content. If I were to return to my previous context and teach ecocomposition to students who share, or are at least familiar with, our current location and the selected places of their classmates, I might increase the number of visual tools we use throughout the class. As stated, in my ecocomposition course that was aimed at multilingual and international students, I oftentimes showed images or YouTube clips depicting certain US settings that were mentioned in certain readings, and asked students to incorporate images of their places into most of their writings or share them with peers (and me) via the class computer, so we could all become acquainted with the spaces that our students selected for their writings or that were dear to them. For a more homogenous student group where writers might be familiar with the appearance of a peer’s selected place, the spaces might not be unknown and new to the class. However, each student writer might see a space through their own eyes and associate it with certain experiences that then ascribe unique and idiosyncratic meaning to it that others can then also learn, benefit, and gain meaning from. Adding visuals added a different level of peer comprehension of their classmate’s places, the significance they attribute to their self-selected spaces, and what this might imply for themselves.

What seemed most central to the students’ learning, integrating, and valuing was the course’s need for their participation, input, prior knowledge, and engagement. As with my previous environmental writing courses, this one too demonstrated that it is crucial to design ecocomposition courses that are extremely student-centered and rely on student involvement for progress. According to the data, the assignments, which mostly dealt with the students’ reflection on their own places and self, were perceived as a welcomed challenge that was accompanied with joy, enthusiasm, interest, curiosity, grit, and even with gratitude. Having a deep understanding of the student writer demographic characteristics was vital to the success of the course!

References

Bartels, A. K. & Parker, K. A. (2012). Teaching sustainability, teaching sustainably. Sterling, VA: Stylus.

Balgopal, M. M. & Wallace, A. M. (2009). Decisions and dilemmas: using writing to learn activities to increase ecological literacy. Journal of Environmental Education, 40(3), 13-26.

Bruce, H. E. (2011). Green(ing) English: voices howling in the wilderness? The English Journal, 100(3), 12-26.

Cahalan, J. M. (2008). Teaching hometown literature: A pedagogy of place. College English, 70(3), 249-274.

Cooper, M. M. (1986). The ecology of writing. College English, 48(4), 364-375.

Devet, B. D. (2011). Redefining the writing center with ecocomposition. Composition Forum, 23, 1-16.

Devet, B. D. (2014). Using metagenre and ecocomposition to train writing center tutors for writing in the disciplines. Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, 11(2), 1-7.

Dobrin, S. I. (2001). Writing takes place. In Weisser, C. R., & Dobrin, S. I. (Eds.) Ecocomposition (pp. 11-25). New York, NY: State University of New York.

Dobrin, S. I. (2011). Postcomposition. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press

Dobrin, S. I., & Weisser, C. R. (2002a). Breaking ground in ecocomposition: Exploring relationships between discourse and environment. College English, 64(5), 566-589.

Dobrin, S. I., & Weisser, C. R. (2002b). Natural discourse. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Fleckenstein, K. S., Spinuzzi, C., Rickly, R. J., & Papper, C.C. (2008). The importance of harmony: an ecological metaphor for writing research. College Composition and

Communication, 60(2), 388-419.

Hothem, T. (2009). Suburban studies and college writing – applying ecocomposition. Pedagogy: Critical Approaches to Teaching Literature, Language, Composition, and Culture, 9(1), 35-59.

Goggin, P. (2009). Introduction. In Goggin, P. (Ed.), Rhetorics, literacies, and narratives of sustainability. New York, NY: Routledge.

Heise, U. 2008. Sense of place and sense of planet – the environmental imagination of the global. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Ingram, A. M. (2001). Service learning and ecocomposition: Developing sustainable practices through inter- and extradisciplinary. In Weisser, C. R., & Dobrin, S. I. (Eds.)

Ecocomposition (pp. 209-223). New York, NY: State University of New York.

IPCC, 2018: Global warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty [V. Masson-Delmotte, P. Zhai, H. O. Pörtner, D. Roberts, J. Skea, P.R. Shukla, A. Pirani, W. Moufouma-Okia, C. Péan, R. Pidcock, S. Connors, J. B. R. Matthews, Y. Chen, X. Zhou, M. I. Gomis, E. Lonnoy, T. Maycock, M. Tignor, T. Waterfield (eds.)].

IPCC, 2014: Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Core Writing Team, R.K. Pachauri and L.A. Meyer (Eds.)]. IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland, 151

Ivanic, R. (1998). Writing and Identity: the discoursal construction of identity in academic writing. Philadelphia, PA: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Johnson-Sheehan, R. (2007). Composing nature. The Writing Instructor.

Klahr, D. (2012). Sustainability for everyone: Trespassing disciplinary boundaries. In Bartels, K. A. & Parker, K. A. (Eds.) Teaching Sustainability Teaching Sustainably (p. 19-30). Sterling, VA: Stylus.

Lake, D. (2012). Sustainability as a core issue in diversity and critical thinking education. In Bartels, K. A. & Parker, K. A. (Eds.) Teaching Sustainability Teaching Sustainably (pp. 31-40). Sterling, VA: Stylus.

Lovelock, J. (1979). Gaia: a new look at life on Earth. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Lovelock, J. (2009). The vanishing face of Gaia: A last warning. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Mauk, J. (2003). Location, location, location: The “real” (e) states of being, writing, and thinking in composition. In Vandenberg P., Hum, S., Clary-Lemon J. (Eds.), Relations, locations, positions (pp. 198-225). Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English.

Moe, P. W. (2011). Com”position”, ecocomposition, Aristotle, and the first-year writing course. Composition Forum, 24, 1-21.

Owens, D. (2001a). Sustainable Composition. In Weisser, C. R., & Dobrin, S. I. (Eds.) Ecocomposition (pp. 27-37). New York, NY: State University of New York.

Owens, D. (2001b). Composition and sustainability. Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English.

Park, G. (2013). “Writing is a way of knowing”: Writing and identity. English Language Teachers Journal, 67(3), p. 336-345.

Rioux, Y. (2019). “Writing makes it easier to relate to the environment” – The Valuable Role of the Composition Classroom in our Threatened Environment. Journal of Sustainability Education, 20.

Rioux, Y. (2017). Native American Rhetoric and Ecocomposition: Exploring Sustainable Ideologies. Working Papers in Composition & TESOL, Spring.

Rioux, Y. (2016 a). Multigenre Writing in the Place-Based Ecocomposition Classroom. Writing on the Edge, 26 (2), 34-51.

Rioux, Y. (2016 b) Combining Places – Teaching Ecocomposition in the Multilingual Classroom. Wisconsin Journal of English, 58 (1), 12-19.

Rowland, L., Millner, J., Hill, N., Towne, A., Wohlpart, J. A. (2009). Approaches and practices for infusing sustainability into a writing programme. Journal of Education for sustainable development, 3, 223-230.

Originally from Augsburg, Germany, Yasmin Rioux moved to the USA to study Environmental Science, but eventually received a degree in English and Communication. She holds an MA in Communication and Ph.D. in English – Composition and Applied Linguistics from Indiana University of Pennsylvania. Yasmin has been researching and writing about ecocomposition and has presented her work at various conferences. She is currently the Chair of the Department of Interdisciplinary Studies at Divine Word College where she also teaches writing. When not working, Yasmin loves to hike and explore with her husband and wonderful children. yrioux@dwci.edu

Originally from Augsburg, Germany, Yasmin Rioux moved to the USA to study Environmental Science, but eventually received a degree in English and Communication. She holds an MA in Communication and Ph.D. in English – Composition and Applied Linguistics from Indiana University of Pennsylvania. Yasmin has been researching and writing about ecocomposition and has presented her work at various conferences. She is currently the Chair of the Department of Interdisciplinary Studies at Divine Word College where she also teaches writing. When not working, Yasmin loves to hike and explore with her husband and wonderful children. yrioux@dwci.edu