Building an Indigenous Traditional Ecological Knowledge Initiative at a Research University: Decolonization Notes from the Field

Link to Table of Contents: March 2018, Decolonization Issue

Jacob Blackhorn JSE March 2018 Decolonizing Issue PDF

Abstract: In this article, we discuss the importance of Indigenous traditional ecological knowledge as the foundation of sustainability education, and we describe the need for, and successful efforts to, begin building an Indigenous Traditional Ecological Knowledge initiative at a research university. We share the guiding theoretical framework of our work, and the three goals of the initiative. We note the tensions involved in crafting a vision statement that a diverse group of faculty, staff, and students can all uphold in our collective work. We conclude with a description of our next planned steps for the initiative, and our hopes that this work will help decolonize sustainability education.

Keywords: traditional ecological knowledge, Indigenous knowledges, collaboration, institution building, social justice, higher education

Funding acknowledgement: The authors acknowledge the support of the 2017 Interdisciplinary Award in the Humanities and Social Sciences (Jacob, PI) funded by the Office for Research and Innovation at the University of Oregon through the support of the University of Oregon Foundation.

Introduction: Indigenous Traditional Ecological Knowledge is a Gift

When the Creator was preparing to bring forth people onto the earth, He called a grand council of all Creation. From them, Creator asked for a gift for these new creatures—a gift to help the people survive, since they would be quite helpless and require much assistance from them all. The very first to come forward was Salmon, who offered his body to feed the people. The second to come forward was Water, who promised to be the home to the salmon. In turn, everyone else gathered at the council gave the coming humans a gift, but it is significant that the very first two were Salmon and Water. In accordance with their sacrifice, these two receive a place of honor at traditional feasts throughout the Columbia Basin. (Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission, 2017)

We begin our manuscript with this beautiful and powerful Creation Story that is shared across several Tribal peoples in the Pacific Northwest, where we live and work. As we reflect on the theme of the Journal of Sustainability Education special issue, Decolonizing and Sustainability Education, we return to an understanding of traditional ecological knowledge learned in both of our Tribal communities: that our traditional cultures hold within them teachings that can sustain humans’ ability to life and thrive on Mother Earth. Indigenous traditional ecological knowledge represents a unique trusted relationship with the natural world that is a cultural, spiritual and reciprocal endeavor (Whyte, 2013; Turner, Ignace, & Ignace, 2000). Yet, too often, we see traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) dismissed, ignored, or trivialized, with perhaps only marginal inclusion in university curricula. We view this as highly problematic for the future of sustainability education, and we encourage all sustainability educators to respectfully seek ways to place TEK at the center of curricular discussions. An additional problem we note, and discuss below, is that even when faculty and students who do meaningfully engage with traditional ecological knowledge and partnerships with Tribal peoples, too often we fall victim to the “silo effect” prominent in universities, and we work in isolation from one another. We fail to build the community needed on our campus that could truly transform our ability to decolonize education, and in doing so make a profound contribution to sustainability education. In this paper, we discuss our work to build an initiative that can help us address these interwoven problems.

We view this paper as a report from the field, in which we describe and analyze our efforts over the past ten months to build an Indigenous Traditional Ecological Knowledge (ITEK) initiative at our research university, the University of Oregon (UO). We analyze our efforts, and the context in which we work, using a decolonizing methodological framework, as proposed by Linda Tuhiwai Smith (Smith, 2012). Our hope is that by turning a reflexive lens upon our work we will be able to better envision and articulate our own decolonizing praxis, which can help propel our work to greater impact and longevity. We also hope that our paper can serve as a way to reach out and build community among other educators who are working in a similar capacity to enrich their educational institutions and communities with traditional ecological knowledge projects and initiatives. In doing so, we enact what Shawn Wilson identifies as core to Indigenous research: relationality and relational accountability (Wilson, 2008, p. 6). It is our belief that if we want to decolonize sustainability education, then we must attend to Indigenous research methodological and epistemological insights. This results in transformative and empowering research process and results because “[r]esearch by and for Indigenous peoples is a ceremony that brings relationships together” and “Indigenous epistemology is all about ideas developing through the formation of relationships” (Wilson, 2008, p. 8).

Critical History of Indigenous Traditional Ecological Knowledge at UO

On the University of Oregon campus, there are impressive examples of longstanding research partnerships with Northwest Tribal peoples that support Indigenous self-determination and understand the value of traditional ecological knowledge. A few examples described in academic literature include the rich language revitalization partnerships in place at the Northwest Indian Language Institute (Jacob, 2013; Jansen & Beavert, 2010) and Indigenous environmental theater (May, 2014). However, there are many more examples of research and teaching partnerships that are not well-known, published in the academic literature, or acknowledged as important beyond a very small community on campus. The everyday experience within universities tends to erode communities of support that work toward anything resembling decolonization. As Leanne Simpson argues, universities are “systems that are primarily designed to produce communities of individuals willing to uphold settler colonialism” (Simpson, 2014, p. 1). The result, too often, is “academic participation in Indigenous dispossession” (Arvin, Tuck, & Morrill, 2013, p. 8). This is the challenge facing everyone who wants to work towards decolonization, whether within sustainability education, or in other fields: how can we transform our educational institutions so they are not perpetuating Indigenous dispossession? We view traditional ecological knowledge as the ideal foundation of sustainability education to address this problem. It is only when we take Indigenous teachings seriously that we can transform our educational systems so that Indigenous self-determination is truly valued and Indigenous peoples, and allies, learn to use education as a “tool of resurgence and sovereignty” (Scully, 2012, p. 148) that supports Indigenous self-determination, rather that upholding settler colonialism (Wolfe, 2006).

Needing an Opportunity to Build Community Around Indigenous Traditional Ecological Knowledge

Despite the tendency for faculty and students to work in relative isolation in their traditional ecological knowledge projects, there is a strong community of Indigenous scholars, students, and staff on the UO campus. Mostly, this community is built around the UO Many Nations Longhouse, a traditional gathering place for Tribal peoples, and designed and built in partnership with the nine federally recognized Tribes in what is now called the State of Oregon. However, longhouse community events tend to be social, or student affairs-based concerns, curricular-focused (i.e. Native American Studies faculty hosting study hall time) or if there is a research focus it tends to be a one-of a kind of event (i.e. Native American Studies students presenting projects from a class; a guest or symposia speaker). A monthly gathering of the Native Strategies group, consisting of all people involved in Native American-related issues on campus, takes place at the longhouse, but due to busy faculty and student schedules, it is difficult for all stakeholders to have consistent and thorough discussions, especially around ongoing research projects. These events and gatherings are all intrinsically important, and help to provide a community space that can alleviate the stress and isolation that Indigenous peoples face in the “whitestream” academy (Tuck & Gaztambide-Fernández, 2013). Regionally, there are differing TEK and traditional knowledge (TK)-focused projects that attend to both Tribal collaborations and providing professional development opportunities to students that meet the needs of Tribal communities, including the Indigenous Wellness Research Institute at the University of Washington, Indigenous Nations Studies Program at Portland State University; the Karuk-UC Berkley Collaborative, and the Center for Indigenous Health, Culture, and the Environment at Heritage University on the Yakama Reservation. In our work to build the ITEK initiative at UO, we have learned from each of these exemplar programs, all of which have purposefully created spaces for TEK and TKs to be seen and heard on university campuses. TEK projects need a home, a community, in which faculty, staff, students, and Tribal community members involved in projects could come together to share ideas, resources, and to dream of a bigger, collective vision in which they can all participate.

Developing an Indigenous Traditional Ecological Knowledge Proposal

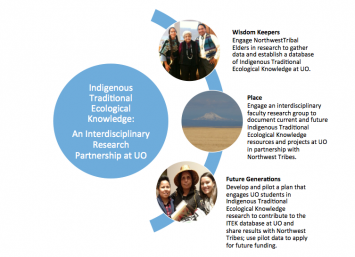

In January 2017, the UO Vice-President of Research and Innovation released a call for proposals to fund an Environmental Humanities award, which would serve as two-years of seed funding, to develop a project that would be expected to seek larger external funding by the end of the award. Using the Native Strategies group as a sounding board, Michelle Jacob shared ideas about what became the proposal entitled: Indigenous Traditional Ecological Knowledge (ITEK): An Interdisciplinary Research Partnership at UO. For over a month, feedback was sought, letters of support were invited, and in-kind support was requested. The response was overwhelming, with 13 faculty named as collaborators who would provide direct support for the project, and three additional letters of support from the Native Strategies group, the Dean of the College of Education, the Dean of the Graduate School, and the Assistant Vice-President and Advisor to the President on Sovereignty and Government-to-Government Relations (a position that resides in the Office of the President at UO). It was through this month-long process of carefully gathering feedback and securing partnerships and support that the proposal was shaped and revised, leading to a theoretical framework that guides the ITEK initiative at UO, and states as the basis of the work that: 1) Tribal Elders are our most precious teachers; 2) Place-based research must benefit Indigenous peoples’ self-determination; 3) Traditional ecological knowledge projects must have an intergenerational teaching and learning focus, to benefit the future generations. The guiding framework is illustrated below in Figure 1. Additionally, we named three goals in the proposal:

Goal I: Convene an interdisciplinary faculty research group to (1) document and compile current UO ITEK research (projects, practices, and collaborations) and, (2) in collaboration with Tribal research partners, identify UO’s ITEK strengths, gaps, and future projects.

Goal II: Engage in ITEK research (pilot projects) and train UO students in appropriate ITEK research by (1) developing and piloting an ITEK research training protocol and (2) engaging students in research projects.

Goal III: Build a database of existing and newly collected ITEK resources at UO.

These goals, and the framework illustrated below, were included in the proposal submitted in February 2017, requesting $24,900 to support the two-year seed project. The funding is designated to support a part-time graduate employee, a part-time work-study student, and meeting costs to provide refreshments to guests and pay for mileage and parking for Tribal partners to attend meetings at UO.

Building the ITEK Initiative

In late-May 2017, near the end of the school year, we received notice that our proposal was funded for our full requested amount, but with funds not available until the new fiscal year in July, and would be administered through the College of Education, the Principle Investigator’s (Jacob) institutional home. Summer 2017 became a time of preparing plans to formally launch the initiative in the Fall, when faculty and students would return to campus. Summertime at UO is when several Tribal partners spend two weeks on campus, however, at the Northwest Indian Language Institute’s Summer Institute. Tribal language teachers and learners gather at UO to be immersed in a rigorous two-week class schedule that covers linguistics and methods for teaching several Indigenous languages. The Northwest Indian Language Institute (NILI) is one of the campus partners of the ITEK initiative, and ITEK planning took place at the summer institute, looking closely at the day-to-day activities taking place and planning ways that the following summer’s institute could meaningfully include ITEK activities, data collection, and sharing.

With plans in place, the next order of business was beginning the process of hiring a graduate employee. During Summer 2017, several changes happened in the College of Education financial management system. Personnel were moved, processes were radically changed, and it was “off cycle” for doing a hiring process of graduate employee, as that process normally takes place in spring. It was impossible for the College’s budget manager to provide an accurate start date, so planning for the initiative needed to move forward, while the hiring process moved along.

The official launch of the ITEK initiative took place in September 2017, during the first week of the Fall term. A learning lesson took place immediately. In the proposal, ITEK meetings were described as “faculty research group” meetings. Michelle received inquiries from staff, from non-tenure track faculty, and from students. Would they be allowed to attend? Additionally, faculty who did ITEK teaching, but not published research, wondered if they should attend. It quickly became apparent that in order to have the inclusive and community-building aspect that was intended, the name of the meeting would have to change. We shifted the language so that we were the ITEK teaching and research group, or more commonly, the ITEK group. At the first meeting, we accomplished part 1 of Goal I. For the first time at UO, we compiled a list and description of all the current ITEK projects. We asked everyone to create a slide about their ITEK project(s) that we could share at the meeting. Ten different programs were represented at our first meeting, with eight different slides describing 17 diverse projects, just to name a few: Indigenous language documentation and revitalization; engaging Indigenous legends/traditional stories in research and teaching; using Indigenous language and concepts in teaching math education; engaging Indigenous philosophies in research and teaching; studying Indigenous diets and traditional foods; collaborating with basket makers to document their artistry. We drafted a vision statement that we hoped to revise at our next meeting, in collaboration with our Tribal partners. We chose a date and time for the next meeting, in November. The hiring process for the ITEK graduate employee concluded in November, and we were pleased that an Indigenous doctoral candidate, Hobie Blackhorn, joined the group in this formal capacity. Hobie immediately established an ITEK listserv, which helped facilitate communication among the growing group, which was dispersed across campus.

The second ITEK meeting brought a new challenge. The weather had turned cold suddenly and several Tribal partners could not attend due to unsafe mountain road conditions. Another Elder Tribal partner had a health issue and could not attend. Despite this challenge, our UO community came together and had a productive meeting and we agreed to share the discussion points with our Tribal partners and invite them back or bring their feedback directly to the group by email or in person. The second meeting, at which we had even greater attendance, included a review of the ITEK project slides that everyone had submitted, and included additional slides that were sent after the previous meeting. We discussed all the projects, did an analysis of our strengths and weaknesses, and turned our attention to revising the vision statement that we had drafted at the previous meeting.

Envisioning ITEK at UO

Crafting a vision statement is a fascinating process. We examined the strengths and weaknesses we saw in our projects, and compared this to the draft we had created at the September meeting. A couple of tensions arose in the discussion. This was not a difficult emotional tension, but rather a tension in the sense that we could understand the differing perspectives on a key point. For example, did we want to specifically name that our ITEK collaborative vision would focus on Northwest Tribes? Did Tribes in California count? What about non-U.S. Tribes? Additionally, did we want to include a statement about the government-to-government responsibility that UO has to the nine federally recognized Tribal Nations of Oregon? Some colleagues and students wanted to keep a Northwest focus; others did not. Some wanted government-to-government language, aligning with, and supporting, how Tribal sovereignty discussions are currently framed in Oregon. Yet others were against this language, in particular those who work with non-federally recognized Tribes in Oregon. Such discussions are common for anyone working in the field of Indigenous Studies. Ultimately, we agreed that the following would be our draft vision statement, and we also agreed that we could revise it at any point in the future, discussing how a new initiative would benefit from a consistent checking in process to make sure our vision was as accurate as possible in describing our work and helping us stay accountable to one another and our Tribal partners. Below, in italics, is our vision statement for our collective ITEK work, as of November 2017:

We are gathering existing teaching and research strengths in order to make visible the important Indigenous Traditional Ecological Knowledge projects taking place at UO. We are committed to building a collaborative Indigenous Traditional Ecological Knowledge research project that is done with care, respect, reciprocity, and in support of Indigenous self-determination in order to serve as a model of Indigenous research methodology in action. The following are central to our vision:

- Indigenous Knowledges belongs to Indigenous communities. Universities must always intentionally respect Indigenous Knowledge Sovereignty and doing so is a responsibility of settler institutions.

- We recognize that our ITEK projects always draw upon place-based Indigenous Knowledge, which is preciously cared for by Tribal Elders, our most revered teachers.

- We support Indigenous language cultivation and revitalization as central to ITEK.

- We value adhering to Free, Prior, and Informed Consent; it is important to build community before we engage community, and return research materials as a way of maintaining respect, reciprocity, and reconciliation.

- In building a larger ITEK initiative at UO, we work in long-term partnership with Tribes and as a regional, national, and internationally renowned resource for students and researchers.

Gathering these resources together allows us to understand our own sense of community. ITEK provides an institutional structure that allows us to better serve Tribal Nations. In doing so, we demonstrate respect for the inherent Sovereignty of all Indigenous peoples.

This vision has its foundation in the following guidelines and protocols: United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, Climate and Traditional Knowledges Workgroup Guidelines, Protocols for Native American and Archival Materials.

Lessons Learned and Next Steps

Over these past 10 months, we have learned a great deal about building the ITEK initiative at UO. It was initially conceived of as a research-based initiative, and indeed this was in response to the funding mechanism, from the Vice-President of Research’s office. However, we quickly learned that teaching is an important component to ITEK at UO. Expanding the scope of the initiative is necessary and important. Faculty (both tenure-track and non-tenure-track) have tremendous gifts to offer the ITEK initiative, in describing and sharing their pedagogical approaches to ITEK in their classrooms and research projects. Additionally, our group meetings are a space where faculty can ask questions about building partnerships with local Tribes, or receive advice on relevant Indigenous knowledge or readings they might respectfully include in their syllabi. Students have much to offer to the initiative, and indeed, they are a crucial part of the framework and goals. Graduate students participate in the ITEK initiative through collaborative research projects with faculty and by engaging ITEK topics in their seminars and individual research agendas; undergraduate students participate through ITEK projects in the classroom, including learning traditional Indigenous stories (legends), and other place-based curricular units, and through service-learning opportunities linked to classes. Our ITEK initiative allows us to connect with one another so that a greater number of faculty and students are in conversation and community with one another, and with Tribal community partners involved in ITEK projects.

All of the lessons we are learning—as we build the initiative—serve as the basis for discussions with the group about our next steps. As a group, we find that existing curricula are typically insufficient for preparing students to meaningfully engage in ITEK research with Tribes. Students need a primer course on Indigenous Research Methodologies (Smith, 2012; Wilson, 2001). This discussion has encouraged us to plan a pilot class on TEK and Indigenous research methodologies we plan to launch in a short course session in Summer 2018, and will engage in formative evaluation in our steps to move forward in offering it as a larger class during the academic year. We hope our work to develop this class can also support Goal II for the project, to develop a training module that we envision as being available, perhaps required, for all faculty, staff, and students who want to do research with Indigenous peoples.

We also are learning about outstanding efforts that are sometimes hidden—such as two examples of Tribal Elder-in-Residence efforts currently underway at UO, one in conjunction with Theater classes, and another in conjunction with Education classes. Having more than one Tribal Elder consistently on campus and advising faculty and students is a powerful strength that we hope to continue, and secure long-term funding for, in our work with Tribal Elders, who are central to successful ITEK work. Based on our work with Tribal Elders, we are designing and planning our first large collaborative group project, a plants and culture workshop that will incorporate storytelling, weaving demonstrations, and ecosystem discussions of several plants that are shared in common as important for several Northwest Tribes. The workshop will bring together an inter-Tribal group of Elders, students, and ITEK initiative participants and we hope the workshop will be a powerful way to engage TEK that builds intergenerational and intercultural connections.

Finally, in our group discussions, we heard accounts of institutional review board (IRB) processes that are not conducive with our projects commitments and goals. For example, an IRB review process that focuses solely on university risk management, rather than power sharing and respectful collaboration and long-term partnership building with Tribes, can actually undermine important TEK research efforts. This issue was reviewed during several working sessions and project members brainstormed and deliberated on best approaches to address these concerns. We developed a survey to assess current problems and future needs on this issue. One promising direction is for our group to work with UO’s Assistant Vice-President and Advisor to the President on Sovereignty and Government-to-Government Relations to prepare suggestions for the IRB process when reviewing research plans with Tribal partners. We are excited about all the possibilities for our remaining 16 months of funding in the seed project.

Conclusion

As we conclude our report from the field, our thoughts return to the Creation Story we shared to open our paper. We view our work as a spiritual responsibility to Salmon, to Water, and to all Indigenous peoples who have lived on and cared for this land that we now inhabit. The hopes and dreams of our ITEK initiative are rooted in an understanding of how precious traditional ecological knowledge is. We value and respect it, and want to build a caring and supportive community at UO who can collectively engage in this work. We hope to build an initiative that will decolonize sustainable education. We agree that sustainable education is a “transformative learning process that equips students, teachers, schools, and informal educators with the knowledge and ways of thinking that society needs to achieve economic prosperity and responsible citizenship while restoring the health of the living” (Cloud, 2014, p. 1). However, we want to add our critical Indigenous perspectives, and critical hope, to this vision. Doing so will allow us to engage in sustainability education that supports Indigenous self-determination, and benefits all peoples who live on Indigenous homelands. This vision of education is one that will serve as a gift in relationality and respect.

References

Arvin, M., Tuck, E., & Morrill, A. (2013). Decolonizing Feminism: Challenging Connections between Settler Colonialism and Heteropatriarchy. Feminist Formations, 25(1 Spring), 8-34.

Cloud, J. (2014). The Essential Elements of Education for Sustainability (EfS) Editorial Introduction from the Guest Editor. Journal of Sustainability Education, 6.

Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission. (2017). We are all Salmon People. Retrieved from http://www.critfc.org/salmon-culture/we-are-all-salmon-people/

Jacob, M. M. (2013). Yakama Rising: Indigenous Cultural Revitalization, Activism, and Healing. Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press.

Jansen, J., & Beavert, V. (2010). Combining the goals of language documentation and language teaching: A Yakima Sahaptin case study. In S. Rivera-Mills & J. A. Trujillo (Eds.), Building Communities and Making Connections (pp. 62-80). Newcastle upon Tyne, UK: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

May, T. (2014). Salmon is Everything: Community-Based Theatre in the Klamath Watershed. Corvallis, OR: Oregon State University Press.

Scully, A. (2012). Decolonization, reinhabitation and reconciliation: Aboriginal and place-based education. Canadian Journal of Environmental Education, 17, 148-158.

Simpson, L. B. (2014). Land as pedagogy: Nishnaabeg intelligence and rebellious transformation. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, 3(3), 1-25.

Smith, L. T. (2012). Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples (2nd ed.). London: Zed Books.

Turner, N. J., Ignace, M. B., & Ignace, R. (2000). Traditional ecological knowledge and wisdom of aboriginal peoples in British Columbia. Ecological Applications, 10(5), 1275-1287.

Tuck, E., & Gaztambide-Fernández, R. A. (2013). Curriculum, Replacement, and Settler Futurity. Journal of Curriculum Theorizing, 29(1), 72-89.

Whyte, K. P. (2013). On the role of traditional ecological knowledge as a collaborative concept: a philosophical study. Ecological Processes, 2(7), 1-12.

Wilson, S. (2001). What is indigenous research methodology? Canadian Journal of Native Education, 25(2), 175-179.

Wilson, S. (2008). Research Is Ceremony: Indigenous Research Methods. Halifax, Canada: Fernwood Publishing.

Wolfe, P. (2006). Settler colonialism and the elimination of the native. Journal of Genocide Research, 8(4), 387-409.

Michelle M. Jacob (Yakama), PhD, is Professor of Indigenous Studies and Director of the Sapsik’ʷałá (Teacher) Education Program in the Department of Education Studies at the University of Oregon, where she is also Affiliated Faculty in Ethnic Studies and Environmental Studies, and leads the university’s Indigenous Traditional Ecological Knowledge Initiative. Michelle’s research areas of interest include: Indigenous educational frameworks, Indigenous research methodologies, traditional ecological knowledge, health, Native feminisms, and decolonization. Michelle’s two books, Yakama Rising: Indigenous Cultural Revitalization, Activism, and Healing, and, Indian Pilgrims: Indigenous Journeys of Activism and Healing with Saint Kateri Tekakwitha, are both published by the University of Arizona Press.

Contact: mjacob@uoregon.edu

Michelle M. Jacob (Yakama), PhD, is Professor of Indigenous Studies and Director of the Sapsik’ʷałá (Teacher) Education Program in the Department of Education Studies at the University of Oregon, where she is also Affiliated Faculty in Ethnic Studies and Environmental Studies, and leads the university’s Indigenous Traditional Ecological Knowledge Initiative. Michelle’s research areas of interest include: Indigenous educational frameworks, Indigenous research methodologies, traditional ecological knowledge, health, Native feminisms, and decolonization. Michelle’s two books, Yakama Rising: Indigenous Cultural Revitalization, Activism, and Healing, and, Indian Pilgrims: Indigenous Journeys of Activism and Healing with Saint Kateri Tekakwitha, are both published by the University of Arizona Press.

Contact: mjacob@uoregon.edu  Hobie Blackhorn (Northern Cheyenne) is a Doctoral Candidate at the University of Oregon’s College of Education, in Secondary Special Education and Transition. His interests include the importance of Family and Community involvement in culturally relevant planning with transitioned aged Native American youth. Hobie serves as the Graduate Employee for the University of Oregon Indigenous Traditional Ecological Knowledge Initiative.

Hobie Blackhorn (Northern Cheyenne) is a Doctoral Candidate at the University of Oregon’s College of Education, in Secondary Special Education and Transition. His interests include the importance of Family and Community involvement in culturally relevant planning with transitioned aged Native American youth. Hobie serves as the Graduate Employee for the University of Oregon Indigenous Traditional Ecological Knowledge Initiative.