Fake Climate News: How Denying Climate Change is the Ultimate in Fake News

Link to the JSE April 2020 Ecomedia Literacy Table of Contents

After the 2016 US-presidential election and Brexit referendum, fake news emerged as a quintessential democratic problem that media literacy was tasked to solve. The broad social concern about fake news acknowledges that the public sphere is a kind of commons that requires tending, and reminds us of the human (and civic) need for authenticity, honesty, clarity, and fairness in our shared discourses. In light of the perceived danger to democracy that fake news embodies, increasingly media literacy is seen as fundamentally about cultivating civic engagement skills. In addition to improving the news and information ecosystem of social media, media literacy promotes critical thinking skills and fundamental research techniques to distinguish legitimate and authentic information from propaganda, disinformation, hoaxes, lies, and blatant manipulation.

Unfortunately, these debates over simplify the larger problem of fake news, and sets up a false dichotomy between “fake” and “real” or “true” and “false” that disregards legitimate critiques of established news organizations or pits “old” versus “new” media. The proliferation of climate disinformation and detrimental environmental media coverage has been perpetuated by traditional gate keepers of so-called real news. Moreover, as David Buckingham (2019) argues in The Media Education Manifesto, the problem with fake news, propaganda and disinformation spreading on platforms like Facebook cannot be addressed by conventional media literacy alone:

Media literacy is not simply a matter of knowing how to use particular devices, whether in order to access or to create media messages. It must also entail an in-depth critical understanding of how these media work, how they communicate, how they represent the world, and how they are produced and used. Understanding the media today requires us to recognize the complexity of modern forms of ‘digital capitalism.’ And if we really want citizens to be media literate, we need comprehensive, systematic and sustained programmes of media education as a basic entitlement for all young people. (p. 3)

In terms of addressing fake climate news, we believe critical media literacy and media reform need to be holistically combined to create a healthy media ecosystem that can adequately address the climate crisis. Combining these approaches promotes ecological ethics and education for sustainability, which is what differentiates media literacy from ecomedia literacy. Sustainability education promotes eco-citizenship, which means embodying sustainable behaviors and cultural practices that shape and promote ecological values within the interconnected realms of society, economy and environment. Ecomedia Literacy supports learners to make sense of how everyday ecomedia practice impacts our ability to live sustainably within earth’s ecological parameters for the present and future. Ecomedia Literacy proposes that media literacy can highlight how on a daily basis we encounter the interrelationship between media and living systems (López, 2014).

Fake Climate News

The term “fake news” became popular during the 2016 election, when it was used to describe hoaxes, conspiracies and disinformation that went viral. These were reports people created and disseminated for the intended purpose of fooling the public for political and/or economic gains, such as the fictitious Pizzagate and the false Papal endorsement of candidate Trump. The New York Times has called fake news, “a neologism to describe stories that are just not true” which they suggest has since been “co-opted to characterize unfavorable news” (Ember, 3 April 2017). Writing for Common Dreams, Neal Gabler (30 November, 2016) provides a more critical analysis, arguing that fake news is an attack on truth that is intended “to destroy truth altogether, to set us adrift in a world of belief without facts, a world in which there is no defense against lies.” It is important to consider who would benefit from a post-truth era in which science and facts are free for any interpretation. In the absence of accountability to facts or evidence, it is highly likely that those who control the airwaves and algorithms will define reality and truth as best fits their interests.

“Fake news” and “alternative facts” can be devastating to issues in which understanding observable facts and knowing scientific truth is essential, such as anthropocentric climate change. Astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson challenges the current attack on science and truth in a short video called, Science in America.

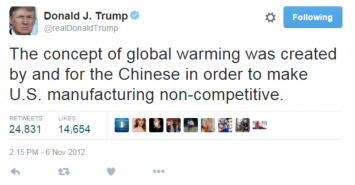

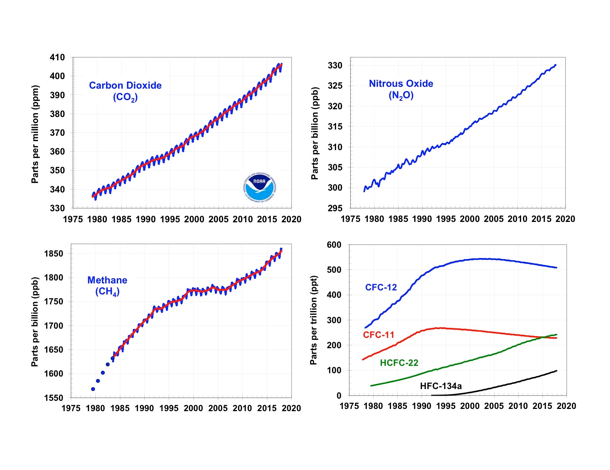

For decades scientists have reported the data, facts, and evidence that human caused CO2 emissions are increasing the temperature of our planet. And yet a small powerful group of individuals have managed to create doubt in public perceptions with unfounded claims that ignore the scientific evidence. This false notion of a controversy and uncertainty, as Naomi Oreskes and Erik Conway (2010) have written about in their book, Merchants of Doubt, is not simply misinformation, it is actually a well-organized campaign of disinformation. When the president of the United States makes claims that are obviously false and completely unsubstantiated (such as crowd sizes, illegal voting, wiretapping, and climate change denials), he challenges the power of truth and honesty that the rule of law is based on. When media outlets repeat and disseminate these lies, they contribute to undermining a key foundation of democracy. These are actions that when unchecked and allowed to continue can only benefit those in power by allowing them to choose the versions of reality that best meet their political and financial interests.

A Healthy Media Ecosystem: The Need for Media Reform

The Nation and Columbia Journalism Review have initiating the Covering Climate Now Project to transform the media’s coverage of the climate crisis. They are responding to shoddy reporting and a dearth of environmental coverage over the past 30 years. For example, in the 2018 there was a 45% drop in climate crisis coverage by the three major US TV networks (Fox decreased from just 260 minutes in 2017 to 142 minutes in 2018). The liberal media watchdog group, Media Matters for America, has been generating annual reports that show how little coverage there has been. In one egregious example, they reported that “ABC’s World News Tonight spent more than seven minutes reporting on the birth of royal baby Archie in the week after he was born — more time than the program spent covering climate change during the entire year of 2018“). Reporting for The Nation, Mark Hertsgaard and Kyle Pope point out that in 1988 climate change was big news. Earth was Time Magazine‘s “Planet of the Year” and climate science was reported on the front page of the New York Times. But since 1990 we have had a 41% increase in greenhouse gas emissions.

While it could be argued that in 1990 it would have been easier (and cheaper) to decarbonize our economy and develop an alternative energy path, we may have waited too long to act. And the media is partly to blame. In their role as watchdog and Fourth Estate, the mainstream and corporate media was manipulated by Big Carbon, whose strategy (honed by the tobacco and chemical industries) was to create doubt about climate science, and hence delay action. Unfortunately, this was particularly an American failure. Part of this relates to conventional journalistic practice of being “fair and balanced” by allowing different sides of the climate discussion equal time (even calling it a “debate” concedes too much to the dirty energy industry). This leads to false equivalency. From 1988 to 2002, 53% major newspapers gave equal attention to both “sides” of climate debate (imagine giving flat earthers this much airtime). On Last Week Tonight, John Oliver brilliantly commented on this absurdity when he demonstrated what a mathematically representative climate change debate would look like. Rather than have two people facing off against each other (which visually gives them equal weight), he brought on stage 97 climate scientists to debate three scientists representing the skeptic/denial side.

Most absurdly, there was not one single question about the climate during any of the 2016 presidential debates. Luckily there’s a shift in public perception, especially after the so-called 2018 “blue wave” in Congress, which elevated policy proposals like the Green New Deal. But likely due to recent reports from the IPCC and United Nations, coupled with the savvy social media strategy of climate strikers and emerging civil disobedience from Extinction Rebellion, every Democrat running for President in 2020 now has a climate platform. In 2019, CNN hosted a climate crisis town hall with 2020 Democratic Party presidential candidates, despite the Democratic National Committee banning any dedicated debates to climate change.

But more importantly, if we want to mobilize the public to take climate action, media reform has to be in the mix. Like laws governing environmental protections, media reform means intervention into how the media system is regulated and financed. It also means that media organizations themselves need to change their internal practices, as The Guardian recently did by changing its style guide regarding how it uses language to report on the climate crisis. Instead of using the terms “climate change” and “global warming,” they now refer to the problem as: “climate emergency,” “climate crisis,” and “global heating.” According to Katharine Viner, editor-in-chief, “We want to ensure that we are being scientifically precise, while also communicating clearly with readers on this very important issue” (Carrington, 2019). Along with changing their terminology, they are also providing a daily record of the global carbon dioxide levels in their weather pages.

The Nation’s Hertsgaard and Pope lay out the clear challenge to news organizations:

What are the climate stories that will resonate with viewers, listeners, and readers? What do those stories look like, concretely, and how can they be different from a status quo that is clearly failing? And even if journalists can figure out a new climate-coverage playbook, can they surmount the widespread public distrust of the press and the budget cutbacks that are ravaging newsrooms across the country?

They offer the following suggestions that are helpful for media literacy critiques and journalism classes:

- The economic structure of the mainstream media (MSM) is threatening climate coverage.Allocation of resources leads to newsroom cuts, eliminating beat reporters, defunding investigative journalism, news deserts (loss of local news sources), closure of news bureaus in places most affected by climate chaos (i.e. poor and rural regions), and too much reliance on short-term stories (and Twitter) instead of long-view reporting. The underlying economic structure of the MSM requires maximizing audiences through cheap but popular programming (gossip, sensationalism, reality programming, comedy news, etc.). There needs to be better funding for local coverage (1,300 communities have lost news coverage in the US). This is not to say there isn’t good reporting, there just isn’t enough of it. For positive examples, the authors suggest emulating what works, such as local news weather coverage, The Guardian (including Co2 levels in its weather coverage and its “Keep it in the Ground” series), Chris Mooney at The Washington Post , The New York Times multimedia presentations, and MSNBC’s Green New Deal town hall. (Also, see Bill Moyers, “What if reporters covered the climate crisis like Edward R. Murrow covered the start of World War II?“)

- The MSM argument that climate change is a “ratings killer” needs to be challenged. Find better ways to report and tell stories, but don’t blame the audience. Moreover, there is an implicit bargain between the news media and the public that if the public grants the right to use its commonly shared bandwidth and infrastructure to private entities; those entities are expected to provide a public service. Giving Trump disproportionate free coverage and a platform may boost ratings, but it’s toxic to democracy and deadly for the environment. Climate change is full of “drama and conflict” (sit-ins, David-and-Goliath story of oil CEOs vs. scrappy environmentalists) which creates lots of interesting stories to tell.

- Find new and different angles to cover the story.Business reporters can focus on warnings from some bankers and insurance industry concerns for impact on economy and “stranded assets.” National security reporters can cover military studies on the threat of climate change as the number one challenge of the future and the threat multipliers of sea-level rise, refugee crisis, drought and war. They can also investigate the massive carbon footprint of the US military (Hussain, 2019). National and regional coverage can focus on food security (production and safety), health, immigration and sports (i.e. it’s too hot to play baseball in the summer). Furthermore, create diverse (i.e. economic, racial and gender) climate desks and don’t silo climate coverage. Reporters need to get out of the beltway go to the “heartland.”

- Learn science and the facts. Also, make visual more genuine climate scientists showing their research to provide more facts to the public about why scientists are convinced in anthropogenic global warming.

- The status quo of political coverage must change.Horserace journalism focuses too much on who’s winning or losing without dealing with actual policies. Additionally, by allowing for false equivalence on the climate debate, a small, vocal minority sets the agenda. Furthermore, don’t buy into Trump/Republican/Fox spin.

- Climate change is “too depressing.”People tend to shirk from bad news, especially when it’s overly apocalyptic. But by these standards, the MSM has not avoided ginning up fear in their coverage of war and terrorism. Still, a shift to solutions-oriented reporting would be a good start. The media need to fill the “hope gap” and show people that problems are solvable, albeit not as easily or simply as the problem-solving commodities hocked during commercial breaks.

- Point fingers, place blame.Let’s be clear, fossil fuel industry executives have committed crimes against humanity and ecocide. To quote Utah Phillips, “The Earth is not dying, it is being killed, and those who are killing it have names and addresses.”

- Climate crisis should not be treated as a political dispute, but rather a scientific reality.This “underlying error” leaves people with the impression that proposals like the Green New Deal can only be evaluated on whether or not they are acceptable politically. This “tactical framing” against the Green New Deal is “strategy and polling rather than a policy’s substantive benefits” which leads to public cynicism and to being less informed (see Carlos Maza’s insightful analysis of this process). If a politician or pundit gets on the air and says, “climate mitigation is too expensive, there is no money to pay for it,” the immediate response of a journalist should be, “scientists say we have to decarbonize our economy, so if this is too expensive, what is your solution?” As it stands, Green New Deal coverage lacks discussion of the scientific consensus that we need to decarbonize the economy.

Using the ecosystem metaphor, it can be argued that the media ecosystem is weak, and therefore susceptible to “invasive species” like corporate disinformation, propaganda and fake climate news. A healthy ecosystem is resistant to such attacks, assuming that by “healthy” we mean one that strengthens the public sphere and serves the needs of a healthy and resilient society that doesn’t trash the very environment it depends on for survival. In the absence of structural reform, teaching media literacy is not a standalone solution.

So, if the dominance of private-owned, market driven, corporate dominated media is not tenable, what can be done? Canadian journalism scholar and activist, Robert A. Hackett, makes the following recommendations (Journalism and Climate Crisis: Public Engagement, Media Alternatives, eds. Robert A. Hackett, Susan Forde, Shane Gunster, Kerrie Foxwell-Norton.):

- Media need to bridge the “hope gap” by producing stories that promote empathy, hope, solidarity, other-oriented ethics, political efficacy, civic trust, and belief in the possibility of collective action. Unlike the goal of “objectivity,” journalism should motivate public engagement and mobilization. This includes telling local stories, inspiring community action and resistance, and amplifying counternarratives that give meaning, direction and a sense of connection for people becoming active citizens. They should play a role in community building, collective identity formation, and participatory citizenship to help the formation and mobilization of counterpublics and counternarratives.

- Treat media as a “public good” (like roads, airports, etc.).Recognize that they are part of a commons. This includes strengthening alternative media, which provides diversity.

- Shift from event driven image politics to “elaborated explanations, solution-building and pro-climate journalism.”

- Revive trust in a democratic media through reform.This can be achieved with a diverse strategy that includes: giving charity status for non-profit news; allow for a “Citizenship News Voucher” (such as contributing funds to an outlet of choice when filing taxes); create trusts (like The Guardian); set up cross-subsidization schemes by applying small taxes on telecoms, cable subscriptions, advertising or spectrum licenses; increase funding for public broadcasting; and fund multimedia community access centers.

- Support alternative media (through grants, donations, subscriptions, patronage, etc.).There are many great research and news outlets producing excellent research and reporting, like Democracy Now!, Desmogblog, National Environment Reporting Network, and Inside Climate News.

One of the most inspiring media reform manifestos to recently come out was in the form of a letter by Extinction Rebellion’s Clare Farrell to The Guardian on how the BBC can change its climate reporting practices. This is worth quoting in its entirety because it’s a model that can be applied to any media organization:

- The director general, Tony Hall, agree to a meeting with a delegation from Extinction Rebellion to discuss how the BBC can tell the full truth on the climate and ecological emergency.

- The BBC declares a climate and ecological emergency.

- The BBC places the climate emergency as its top editorial and corporate priority by adoption of a climate emergency strategic plan, at the level of urgency placed on informing the public about the second world war.

- The BBC to divest all pension funds, investments and bank accounts from fossil fuel corporations and their bankers.

- The BBC, its subsidiaries and its supply chain to agree to be zero-carbon by 2025.

- The BBC to publish an annual eco-audit of all BBC operations, including summary of key ecological and carbon data.

- The BBC to take a lead on encouraging other national and global media corporations to join the global efforts to save humanity/nature from existential crises.

- The BBC to only allow thinktank spokespersons on air to discuss the climate emergency whose funding is fully transparent. (“The Truth” – Extinction Rebellion)

Finally, media reform also entails breaking up media monopolies and turning companies like Facebook and Google into public utilities. The domination of media oligarchs leads to a kind of monoculture in the media ecosystem.

Using Critical Media Literacy to Combat Fake Climate News

The most dangerous “fake news” being repeated in commercial media, social media, and now government sponsored media is the denial of human caused climate change. Fossil fuel companies have already spent billions buying rights to drill for oil and gas all over the world, something that will be devastating to our planet if it is allowed to continue. These multibillion-dollar corporations stand to lose large amounts of money if they do not adapt their practices as countries shift to renewable energy. Even though extracting and burning fossil fuels has been proven to be the primary cause of global warming, these corporations are spending less of their fortunes on switching to cleaner renewable energy and more on trying to convince people that climate change is fake. This challenge to the truth could not be more important at this point to determine the fate of human civilization.

Therefore, we are calling for an educational commitment to critical media literacy as an essential tool to empower students to critically question media and dominant ideologies, such as unregulated capitalism, overconsumption, fossil fuel dependency, and human exploitation of nature. Critical media literacy is a theoretical framework and pedagogical approach to education that promotes social and environmental justice through an inquiry process of questioning and creating alternative media (Funk, Kellner, & Share, 2016). Students at all grade levels can learn to search for truth through accessing multiple sources, triangulating different data, and making informed decisions based on facts, evidence, and research. Critical media literacy can help educators and students see through the smoke screen of “fake news” and “alternative facts” to learn the truth about climate change and take actions before it is too late.

During the 2016 Summer Olympics in Rio de Janeiro, ExxonMobil aired a deceptive television commercial that portrayed an environmentally conscious company, “powering the world responsibly.” In response to this attempt at greenwashing Exxon’s image, ClimateTruth.org created a parody video that exposes the hypocrisy of Exxon’s claims by using the same music and style of the original commercial with additional text that challenges their assertions of environmental responsibility. Sharing these two short videos with students can be a powerful way to engage youth in critically thinking about media messages about the environment and the role of fossil fuel companies in contributing to the problems of climate change. The Climatetruth video can be an excellent example of how students can become adbusters themselves and create their own media to challenge misleading attempts by industry and government to greenwash reality and deny the science about anthropomorphic climate change.

There are many resources available to critique climate deniers and critically analyze the news such as Project LookSharp’s (2010) Media Construction of Global Warming: A Media Literacy Curriculum Kit, The National Center for Science Education’s website and resources Dealing with Denial and the Scientific Trust Tracker. For additional resources, activities, and readings related to critical media literacy and climate change, go to the Teaching Climate Change to Adolescents: Reading, Writing, and Making a Difference (Beach, Share, & Webb, 2017) website.

It has been our experience that conventional media literacy approaches have eschewed advocating media reform or politics. But critical approaches to media should entail a critique of the media ecosystem and propose solutions. Teachers of journalism and media literacy should consider that the current status quo is not tenable for confronting the global ecological crisis. This article uses fake climate news as a lens that can help guide media teachers to consider how a critical analysis of the media invites a discussion of how to fix the system so that students that are operating from an eco-ethical framework can work towards solutions.

References

Beach, R., Share, J., & Webb, A. (2017). Teaching climate change to adolescents: Reading, writing, and making a difference. New York, NY: Routledge. (Co-distributed with NCTE).

Buckingham, D. (2019). The media education manifesto. Cambridge, UK; Medford, MA: Polity.

Carrington, D. (2019, May 17). Why the Guardian is changing the language it uses about the environment. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/may/17/why-the-guardian-is-changing-the-language-it-uses-about-the-environment

Ember, S. (3 April, 2017). This is not fake news (but don’t go by the headline). New York Times, Education Life, EDTALK. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2017/04/03/education/edlife/fake-news-and-media-literacy.html

Funk, S., Kellner, D., & Share, J. (2016). Critical media literacy as transformative pedagogy. In M. N. Yildiz & J. Keengwe (Eds.), Handbook of Research on Media Literacy in the Digital Age. Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

Gabler, N. (30 November 2016). Who’s really to blame for fake news? Look in the mirror, America. Common Dreams. Retrieved from http://www.commondreams.org/views/2016/11/30/whos-really-blame-fake-news-look-mirror-america

Hussain, M. (15 September 2019). War on the world: Industrialized militaries are a bigger part of the climate emergency than you know. The Intercept. Retrieved from https://theintercept.com/2019/09/15/climate-change-us-military-war/

Hackett, R., Forde, S., Gunster, S., & Foxwell-Norton, K. (2017). Journalism and Climate Crisis. London; New York: Routledge.

López, A. (2014). Greening media education: Bridging media literacy with green cultural citizenship. New York: Peter Lang.

Oreskes, N., & Conway, E. M. (2010). Merchants of doubt: How a handful of scientists obscured the truth on issues from tobacco smoke to global warming. New York, NY: Bloomsbury Press.

Antonio Lopez, Ph.D. is a leading international expert of media education. With a research focus on bridging sustainability with media literacy, he is an experienced curriculum designer, educator, trainer, theorist, researcher and public speaker. As an author and blogger he has written numerous academic articles, essays and three books: Mediacology: A Multicultural Approach to Media Literacy in the 21st Century, The Media Ecosystem: What Ecology Can Teach Us About Responsible Media Practice, and Greening Media Education: Bridging Media Literacy with Green Cultural Citizenship. He is currently Chair and Associate Professor of Communications and Media Studies at John Cabot University in Rome, Italy. Visit his website at: https://antonio-lopez.com/

Antonio Lopez, Ph.D. is a leading international expert of media education. With a research focus on bridging sustainability with media literacy, he is an experienced curriculum designer, educator, trainer, theorist, researcher and public speaker. As an author and blogger he has written numerous academic articles, essays and three books: Mediacology: A Multicultural Approach to Media Literacy in the 21st Century, The Media Ecosystem: What Ecology Can Teach Us About Responsible Media Practice, and Greening Media Education: Bridging Media Literacy with Green Cultural Citizenship. He is currently Chair and Associate Professor of Communications and Media Studies at John Cabot University in Rome, Italy. Visit his website at: https://antonio-lopez.com/  Jeff Share is a Faculty Advisor in the Teacher Education Program at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). His research and practice focus on preparing educators to teach critical media literacy in K-12 education, for the goals of social and environmental justice. An updated second edition of his book, Media Literacy is Elementary: Teaching Youth to Critically Read and Create Media, was published in 2015. Two years later Routledge published the book he co-wrote with Richard Beach and Allen Webb titled, Teaching Climate Change to Adolescents: Reading, Writing, and Making a Difference. Collaborating with Douglas Kellner in 2019, they published, The Critical Media Literacy Guide: Engaging Media and Transforming Education.

Jeff Share is a Faculty Advisor in the Teacher Education Program at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). His research and practice focus on preparing educators to teach critical media literacy in K-12 education, for the goals of social and environmental justice. An updated second edition of his book, Media Literacy is Elementary: Teaching Youth to Critically Read and Create Media, was published in 2015. Two years later Routledge published the book he co-wrote with Richard Beach and Allen Webb titled, Teaching Climate Change to Adolescents: Reading, Writing, and Making a Difference. Collaborating with Douglas Kellner in 2019, they published, The Critical Media Literacy Guide: Engaging Media and Transforming Education.