Applying AASHE STARS to Examine Geography’s “Sense of Place” in Sustainability Education

Table of Contents: Place and Resilience in Sustainability Education, April 2016

BonneyDuram JSE February 2016 Place Issue PDF

Abstract: Geography supports place-based inquiry for the learner, applying the old environmental adage of “think globally, act locally” to environmental problem solving. Many within and outside of the discipline of geography see it as a highly appropriate home for sustainability studies. Yet despite a history of human-environment education, place-based relevancy, and support from professional research or education organizations, studies show that geography does not always take a lead role in sustainability education. In the following, we revisit the contested histories of geography and sustainability education and show support for geography-led sustainability curriculum. The scope of this research is universities which have self-identified as leaders in campus sustainability, using the Association for the Advancement of Sustainability in Higher Education (AASHE) Sustainability Tracking, Assessment, and Rating System (STARS) participation as an indicator. To best understand the current relationship of geography and sustainability studies in higher education, this study examines the role of geography in offering “Sustainability Focused” courses as reported by AASHE STARS institutions with geography programs. The results show that although geography departments are highly utilized when present at an institution, there is still much room for improvement both within geography departments and campus-wide. We then discuss the implication of these findings, both for the discipline of geography and for students of sustainability.

Keywords: sustainability, sustainability education, geography, sense of place, higher education, sustainability reporting

INTRODUCTION

The modern question of sustainability is: “how can we meet the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs?” (WCED 1987). Universities are being called to help answer this question. Led by public commitments like the Talloires Declaration and The UN’s Agenda 21, universities have been long been quantifying and ranking sustainable progress in operations, planning, administration, and student engagement (Wright 2004). Not only are universities pursuing sustainable operations, but are leading social movements and teaching sustainability focused courses. There is a “quiet revolution in teaching and research in sustainability taking place on the university campus” (Basille 2011, 261).

The approach to sustainability education is varied, with sustainability courses found most often in business management, environmental science, engineering, conservation, and political science. It is widely agreed that sustainability studies should be interdisciplinary in nature, focus on the interaction of humans and their resources, and efficiently balance environmental, economic, and social concerns without the significant compromise of any one of those three “pillars” (Filho 2000, Wals and Jickling 2002, Kates 2011, Mulkey 2012).

“Geography,” too, is a well-known word with contested interpretations, often meaning a different course of study for different scholars or different campuses. Geography serves as a bridge between the physical and social sciences and therefore is interdisciplinary in nature, focusing on interactions and interconnections between humans and their environment at various scales (local, regional, global) at present and though time. In modern academia it can take many forms…economic geography, feminist theory geography, study of globalization, etc.; always examining phenomena within both local and global context, and more often utilizing spatial tools. Geographers were the first to describe the “innate faculty” and “learned skill” of “sense of place,” which gives us context for our world and our place in it (Relph 1997). “As a taught skill,” Relph argues, “geographical sense of place has always aimed to grasp both what is good and what is bad in places, then to argue critically for changes that are just and enduring, yet responsive to diverse environments and cultures” (208).

Examining the identities and definitions of sustainability as a goal and geography as a discipline, we hear echoes of one in the other. Indeed, many have noted that the themes and tools of geography lend well to sustainability studies (Manning 1990, McManus 2004, Gregory et al 2002, Selby 2006, Liu 2011, Bennett 2013). The National Research Council, National Council for Geographic Education, National Science Foundation, The Environmental Protection Agency, and other organizations have made calls for the inclusion of geographic theory and tools in sustainability studies. If sustainability is the end, could geography be the means?

Literature suggests that geography has thus far not taken a significant role in sustainability education (Bednarz 2006, McManus 2006, Liu 2011, Bennett 2013). The National Council for Science and the Environment found that out of all 398 Sustainability Specializations and Concentrations offered in the United States, only 3% were housed in Geography units (Vincent, 2012).

Framing sustainability studies within the context of sense of place fosters a feeling of relevancy in student’s lives. This feeling of relevancy often results in positive behavior change (Wheeler et al 2008, Frisk and Larson 2011, Rogers and Bragg 2012). Students become change agents. Further, geography offers an interdisciplinary approach to sustainability studies that perhaps applied or physical sciences cannot. Although the connection to human-environment studies makes geography a natural home for sustainability education, geographers are not taking a lead role in offering sustainability courses in the U.S. If sustainability is not being taught within geography, are students being exposed to interdisciplinary approaches to the subject? Is sustainability being examined within the context of place?

BACKGROUND

Geography and Higher Education

Like environmental sustainability, geography is interdisciplinary in nature and many of the tenets of geography may be found in other disciplines as well (Davis 1906, Bednarz 2006, Liu 2011). Geography has long held a special focus on conservation, and geographic publications in conservation date back as far as the inception of the word, as it is understood today, in the mid-19th century by George Perkins Marsh (Marsh 1864). Widely accepted traditions of geography include spatial analysis, area studies, the man/land relationship, and earth science (Pattison 1964). The Geography Education National Implementation Project, which has defined the most widely used geographic standards for elementary and secondary education in the U.S., includes six key geographic skills: “1) The World in Spatial Terms; 2) Places and Regions; 3) Physical Systems; Human Systems; 5) Environment and Society; and 6) The Uses of Geography” (NCGE 2014).

The geographic human-environment identity has served as an excellent foundation for sustainability studies and sustainable problem solving for many years in the U.S. and abroad. As Turner (2002) points out, geographers in the French tradition, especially, have long seen the benefit in using place-based context to understand the effect of human choice on the environment (Church 1951, Robson 1981). President of the Canadian Association of Geographers, Edward Manning, who believes geography failed to lead the environmental movement of the 1960s, urged his colleagues at his presidential address in 1990 to pursue sustainable development education via the discipline (Manning 1990). Bednarz points out that U.K. geographer Huckle, in response to Agenda 21, likewise encouraged his colleagues, “geography has been given the major responsibility for delivering education for sustainable development” (Huckle 2002, 64 quoted by Bednarz 2006, 239). Bednarz also references Kasimov et al in stating that environmental studies in Russia are divided between the disciplines of geography and engineering (Kasimov et al 2005, Bednarz 2006).

Earth system scientist Andrew Pitman points out that the fact that humans play a significant role and have a significant impact on Earth as a system is common knowledge for geographers but seen as a revelation for non geographers (2005). Pitman lists the unique contributions of geography to this field, and again echoes the “think globally, act locally” mentality in stating that present and future sustainability problems “require information on how populations might change the future, the types of economic growth that may occur, the rate of economic development and the nature of technological change. This information is required at regional detail for the entire globe” (2005, 143). In other words, the innate and learned skill of sense of place is needed. Pitman believes geography is the only discipline that can adequately supply this information.

Support for a geography-led sustainability curriculum is present at the organizational level as well. Bednarz (2006) gives thorough evidence of support from the National Council for Science and the Environment (NCSE), The EPA, and the National Science Foundation, and makes special note that the U.S. EPA has even called specifically for environmental problem solving that is grounded in sense of place (NCSE 2003, 8).

The National Geographic Society approaches sustainable problem solving with a model that is uniquely geographic. National Geographic provides resources to educators that promote environmental problem solving grounded in space-specific context. They call this skill “geo-literacy” (Edelson 2011). National Geographic, in partnership with ESRI, promotes geo-literacy as a means to explore the interactions, interconnections, and implications of sustainable problem solving at a local and global scale (Edelson 2011). National Geographic Society believes that to solve important challenges of our time, one must first have a global perspective and be geo-literate.

The National Research Council Geographical Sciences Committee (NRC 2010 vii, quoted by Barnes 2011, 333) likewise states:

“In the years ahead, geographical tools and techniques will be of vital importance to the effort to monitor, analyze, and confront the unprecedented changes that are unfolding on Earth’s surface.”

Clearly there are connections between sustainability and geography education. Evidence for geography-led sustainability education, however, is less clear.

Liu (2011) examined recent developments in sustainability studies, drawing on surveys from twenty-six sustainability degree programs in the United States and found that only 34% of surveyed institutions even had geography departments at their institution, 15% required a geography class, and 21% required a geography elective class. Liu presented calls within the discipline for more involvement in sustainability education and offered hypotheses for why geography is not more involved in sustainability studies. Key conclusions of Liu’s work are that geography courses are not strongly represented in sustainability curriculum, and should the discipline seek to capitalize on the growing student market interested in sustainability, they can do so by creating courses, integrating sustainability into existing courses, or adopting existing courses as sustainability curriculum. Finally, Liu urged the geographic community that sustainability studies offer an opportunity to recruit and retain students seeking such programs.

Where Liu focused on sustainability education trends reported by a national sustainability group, Bednarz (2006) focused on departmental trends reported by the Association of American Geographers (AAG). Bednarz’s research found that, by most accounts, geographical research of sustainability issues is strong. Evidence for geography-led sustainability courses, however, is weaker.

The National Council for Science and the Environment found that out of all 398 Sustainability Specializations and Concentrations offered in the United States, only 3% were housed in Geography units (Vincent, 2012). The largest grouping, 24%, belonged to Business Administration units, 15% to Engineering, and 14% to Interdisciplinary Environmental Studies (Vincent 2012).

Overall, environmental sustainability has claimed a firm foothold in higher education, and its influence continues to grow. Assessment tools and literature concerning them are emerging. Currently, the Sustainability Tracking, Assessment and Rating System (STARS) produced by AASHE is the most widely used tool in the United States for tracking and comparing sustainability at universities across education and research, physical operations, and administration and planning sectors. AASHE is the premiere professional organization for sustainability practitioners in higher education as well as business partners that work closely with universities and colleges. Although AASHE began as an organization for North America, it now has 825 higher education members and 194 business or non-profit members in North and Central America, Asia and the Middle East, Europe and the U.K., and Australia (AASHE 2014). AASHE first developed STARS in 2007, and describes the tool as follows:

“a voluntary, self-reporting framework for recognizing and gauging relative progress toward sustainability for colleges and universities. It is designed to:

- Provide a framework for understanding sustainability in all sectors of higher education.

- Enable meaningful comparisons over time and across institutions using a common set of measurements developed with broad participation from the campus sustainability community.

- Create incentives for continual improvement toward sustainability.

- Facilitate information sharing about higher education sustainability practices and performance.

- Build a stronger, more diverse campus sustainability community” (AASHE 2012).

Maragakis and van den Dobblesteen found that among sustainability practitioners worldwide, not only is STARS the most recognized university sustainability tracking tool, but it is also considered by many to be the best available tool (2013). Still, the authors stress the need for further research on the validity of assessment tools like STARS, and call for a uniform ranking system. Similarly, Saadation et al (2011) found STARS to be the most popular amongst sustainability professionals, and in an evaluation of the strengths and weaknesses of sustainable higher education assessments, found that STARS, along with the Campus Sustainability Assessment Framework of Canada scored highest for avoiding subjective judgment and for satisfaction of triple bottom line, “including ecological and social performance in addition to financial performance in a particular organization” (138, referencing Filho and Carpenter 2006). The partnership between STARS and the Princeton Review Guide to Green Colleges suggests that STARS status in the U.S. will continue to grow. At present, the, STARS is our best indicator of the state of sustainability education.

Many have recognized the unique potential of geography for sustainability studies. The human-environment tradition of geography and its ability to offer place-based inquiry make it an appropriate, even ideal home for sustainability education. Although there is a great body of sustainability research produced by geographers (Bennett 2013), geography has not emerged as a leader in sustainability curriculum, despite promptings from professional organizations.

METHODS

The purpose of this research is to determine the role of geography departments in sustainability education at universities that self-identify as sustainability leaders. Universities examined in this study are participants in AASHE STARS that have received a sustainability ranking of Bronze, Silver, or Gold.

The following research questions were used:

- What percentage of overall curriculum is devoted to Sustainability Focused courses at Gold, Silver, and Bronze awarded STARS institutions in the United States, and do Gold institutions teach a higher percentage of sustainability classes?

- What departments within STARS universities offer sustainability curriculum?

- At STARS institutions, what proportion of Sustainability Focused courses are taught in geography?

STARS reports sustainability characteristics in four main categories (Education and Research; Operations; Planning, Administration, and Engagement; and Innovation) that contribute to the final score. Universities are then “ranked” by score to indicate progress. This research focused on Category 1, Education and Research; Credits 5: Sustainability Course Identification; 6: Sustainability-Focused Courses; 7: Sustainability-Related Courses. Definitions and Reporting Fields of Sustainability Focused Courses are as follows:

ER6 Sustainability Focused Courses Definition: “This credit recognizes institutions that offer academic courses focused on sustainability. Sustainability-focused courses provide valuable grounding in the concepts and principles of sustainability. These courses educate students about how different dimensions of sustainability relate to and support each other in theory and practice. In addition, these courses help equip students with the skills to weave together disparate components of sustainability in addressing complex issues.

ER 7 Sustainability Related Courses Definition: This credit recognizes institutions that offer courses related to sustainability. Sustainability-related courses help build knowledge about a component of sustainability or introduce students to sustainability concepts during part of this course. They may complement sustainability-focused courses by providing students with in-depth knowledge of a particular aspect or dimension of sustainability (such as the natural environment) or by providing a focus area (such as renewable energy) for a students’ understanding of sustainability from within different disciplines (AASHE 2012, 46).

Reporting Fields: The number of sustainability-focused courses offered (A course may be either sustainability-focused or sustainability-related, not both; a course should be counted only once.)

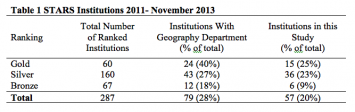

Because Sustainability Focused courses offers a more specific definition, and because some in the sustainability community have criticized STARS for the breadth of courses included in the Sustainability Related category, only course data from the ER6 category Sustainability Focused Courses was used. Data from 2010-2013 participants was used from STARS 1.2, and although version 2.0 was published during the time of this study, all terminology used in this study follows the STARS 1.2 language. Using the public online STARS database, universities were examined in the Gold, Silver, and Bronze categories The purpose of the study was to specifically examine the role of geography in sustainability education, therefore only universities with geography departments were examined. To determine if a university had a geography department, the AAG 2010-11 Guide to Programs was consulted. Canadian institutions and community colleges were omitted. If universities had participated in the STARS assessment more than once, the data from the most recent year were used. Because the data are self-reported, certain reporting inconsistencies necessitated data cleaning. Some universities identified that they were “Not Pursuing” a Sustainability Focused Courses score and thus could not be included in this study. A total 60 Gold, 160 Silver, and 67 Bronze universities are ranked in STARS. Of those, 24 Gold, 43 Silver, and 12 Bronze institutions had geography programs. Eight Gold, seven Silver, and six Bronze universities were omitted due to incomplete data. Thus, a total of 57 universities were examined, 15 Gold, 36 Silver, and 6 Bonze, which have both a geography department and complete data.

The three key areas of focus for the AASHE data were: total sustainability curriculum, geography’s contribution to Sustainability Focused curriculum, and the distribution of other disciplines used to deliver sustainability focused curriculum.

To find total sustainability curriculum, Sustainability Focused and Sustainability Related courses were tallied and then calculated as a percentage of total curriculum at each university using the total course offering figures provided by each STARS participant. The correlation between total sustainability curriculum and Focused curriculum was calculated using Pearson product moment coefficient. Mean total sustainability curriculum and mean Sustainability Focused curriculum were calculated for Gold, Silver, and Bronze institutions, and then for the entire sample. Course offerings by department were tallied for each university and then examined as a percentage of total sustainability curriculum to find which departments were contributing most to total Sustainability Focused course listings.

RESULTS

Total Sustainability Curriculum At STARS Institutions

Using data from ER 6 and ER 7, Sustainability Focused and Sustainability Related Courses, respectively, total sustainability curriculum was calculated as a percentage of total curriculum at each university with a geography program. Then, because the focus of this study was on Sustainability Focused courses, this component was also calculated as a percentage of total courses offered.

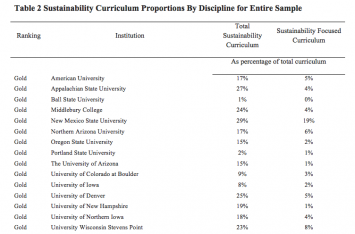

Total sustainability curriculum within the university sample ranged from 1% of the total curriculum (Pennsylvania State University) to 63% of total curriculum (Western Washington University) (see Table 2 for complete list).

PDF: BonneyDuram Table 2 Sustainability Curriculum Proportions By Discipline for Entire Sample

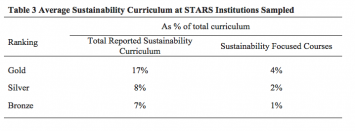

Correlation between total sustainability curriculum and Sustainability Focused courses offered was calculated using Pearson product moment correlation coefficient, which showed a positive relationship between total sustainability curriculum and Sustainability Focused course offerings (r=.50). On average (herein, “average” refers to arithmetic mean), Gold universities reported that 17% of their total curriculum has a sustainability component, 4% of which are Sustainability Focused courses (Table 2). Silver universities report 8% of their curriculum to have a sustainability component, 2% of which are Sustainability Focused courses. Bronze universities report 7% of their curriculum to have a sustainability component, 1% are Sustainability Focused courses.

Role of Geography in Sustainability Focused Curriculum

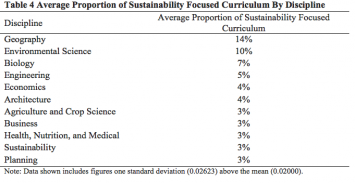

Geography courses were calculated in proportion to all Sustainability Focused courses across all schools, and mean course offerings were calculated. Results showed that Geography departments teach the largest proportion of sustainability courses, averaging 14% of Sustainability Focused Curriculum (Table 3).

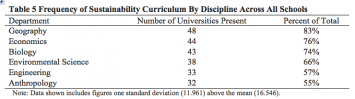

The occurrence of Sustainability Focused courses being taught in each discipline was examined across all schools. Geography departments are offering sustainability focused courses at 83% of universities, the highest occurrence across all disciplines (Table 5).

DISCUSSION

The results show that even though the universities sampled self-identify as committed to sustainability or even leading in campus sustainability, a very small proportion of their total curriculum is devoted to sustainability studies.

The Pearson coefficient analysis compared the total reported curriculum and Sustainability Focused course data percentages and found that a higher proportion of total sustainability curriculum was positively related to a higher percentage of Focused curriculum. Sustainability Focused course data is the best indicator of sustainability course offerings at a university, and these figures were quite low. Gold, Silver, and Bronze universities were only offering 4%, 2%, and 1% of their classes in sustainability-focused arenas. This shows that even though literature suggests an increase in sustainability education in the United States, these fifty-seven campus sustainability champions are offering a very small number of courses and there is much room for improvement. It is possible that universities without geography programs are teaching a much higher percentage of sustainability-courses in other departments: environmental science, engineering, or architecture, for example. Future analysis of course offerings at all STARS rated universities is needed to gain better understanding of the state of sustainability education. Still, literature shows a consensus that geography is an appropriate discipline by which to engage in interdisciplinary studies and teach all three pillars of sustainability (economic, social, and environmental). Further, geography is the natural fit to offer “sense of place” as a lens for environmental problem solving. Therefore, if sustainability studies are indeed taking place outside of geography departments at the universities not sampled, perhaps these students are not receiving an education grounded in interdisciplinary problem solving or place-based inquiry.

Role of Geography in Sustainability Focused Curriculum

The central focus of this study was the role of geography departments in sustainability course offerings. Other studies that have examined sustainability programs from all disciplines have shown only 3% were housed in geography units (Vincent, 2012). The largest grouping, 24%, belonged to Business Administration units, 15% to Engineering, and 14% to Interdisciplinary Environmental Studies (Vincent 2012). This study, however, found that geography departments are housing the largest proportion of Sustainability Focused courses at 14%, followed by Environmental Science at 10%. In comparing the leaders of the Vincent study with data from this study, we see less involvement from Business Administration (3%) and Engineering (5%). This suggests that in universities that have geography programs, geography departments are utilized to teach sustainability courses.

Not only did the geography departments in this study teach the highest proportion of Sustainability Focused courses, but they taught such courses most often across the sample. Meaning, out of the total 57 universities studied, 48, or 84%, of universities offered some proportion of Sustainability Focused courses in geography. It is interesting that not all geography departments taught sustainability focused courses. The reasoning for this is unclear, especially considering four of the nine university geography programs that did not offer Sustainability Focused courses do claim the program specialties that Bednarz suggests lend themselves to sustainability studies (2006).

Applicability of STARS as a Research Tool

This study also gave insight to the utility of STARS as a research tool. Although STARS is the most recognized campus sustainability metric, and by some accounts the best tool, little research has emerged on the effectiveness of STARS or using data reported by STARS. Although STARS 1.2 and 2.0 (launched fall 2013) were created using input from multiple campus sustainability stakeholders, this study reveals that perhaps further development is needed in the Education and Research category.

Out of the sample available for study (79 universities with geography programs), 28% (22 universities) had to be omitted because of missing data, broken links to data, or data in formats that could not be used for this study (a list of course titles, for example, but not including which disciplines the courses were from). Several universities had “Not Pursuing” listed in place of any information in the ER6 and ER7 categories, including at least one university at the Gold level. Education and research are the mission and purpose of colleges and universities, so it seems inconceivable that a university would be awarded a Gold ranking in STARS without including any information on their approach to educating students for sustainability. The recently released STARS 2.0 does offer some increased accountability measures, and more robust definitions of sustainability courses. Still, much work is needed to make STARS a more reliable, time efficient, and accurate research tool.

CONCLUSION

This study revealed that, where geography departments exist, they are taking the lead in offering sustainability curriculum. On average, geography programs are teaching the highest proportion of sustainability focused courses. Literature from both within and outside the discipline of geography suggests that it is a highly appropriate discipline for the increase of sustainability curriculum. Geography is inherently interdisciplinary, has a long history of examining human-environment interactions, offers spatial analysis tools, and supports the “innate faculty” and “learned skill” of sense of place. Still, the figures in this study reveal the vulnerability of geography’s place in sustainability education.

Currently, only a small portion of university curriculum is focused on sustainability (between one and four percent). Of that, geography is only involved in 14% of courses. And finally, only 28% of the 287 ranked STARS participants are four-year institutions offering geography. Sustainability curriculum and geography’s role therein clearly have room to grow. The bigger problem, however, seems not to be the appropriateness or the ability of geography to teach this curricula, but the availability of geography on a university campus. At the end of the day, the ability for geography to teach to sustainability is irrelevant if the departments do not exist.

If geography responds to the growing demand for sustainability curriculum, students will earn an interdisciplinary education focused on environmental problem solving, the ability to understand human-environment phenomena at the local and global level, the aptitude to anticipate and recognize interconnections and implications, an ever growing array of spatial tools, and a rich disciplinary history that encourages students to imagine worlds not yet realized and then to boldly set out for them. Geography is a discipline equipped to offer students place-based inquiry for sustainable problem solving.

Without a doubt, geography has much to offer the sustainability student who aims to “grasp both what is good and what is bad in places,” creating “solutions that are just and enduring, yet responsive to diverse environments and cultures” – the very definition of sense of place (Relph 1997 209).

Bibliography

Association for the Advancement of Sustainability in Higher Education (AASHE). AASHE Member Directory. http://www.aashe.org/membership/member-directory (accessed April 1, 2014).

AASHE. 2012. STARS Version 1.2 Technical Manual. Denver, CO: AASHE.

Association of American Geographers (AAG). 2012. Guide to Programs in Geography in the United States and Canada 2011-2012.

Barnes, T. 2011. This Is Like Déjà Vu All Over Again. The Professional Geographer 63:3, 332-336.

Basile, G. 2012. The Sustainability Professional. Sustainability: The Journal of Record. 5:4, 218-222.

Bednarz, R. 2006. Environmental research and education in US Geography. Journal of Geography and Higher Education 30:2, 237-250.

Bennett, D.E. 2013. Geography and the Emergence of Sustainability Science: Missed Opportunities and Enduring Possibilities. The Geographical Bulletin 54: 99-112.

Church, R.J.H. 1951. The French School Of Geography. Philosophical Library.

Davis, W.M. 1906. An Inductive Study of The Content of Geography. Presidential address at the second meeting of the Association of American Geographers, December, 1905. Bulletin American Geographical Society XXXVIII: 67-84.

Edelson, D. 2011. Geo-Literacy: Preparation for Far-Reaching Decisions. National Geographic, Education Online Resources (NatGeoEd.com), National Geographic Society.

Filho, L.W. 2000. Dealing with misconceptions on the concept of sustainability. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education 1:1, 9-19.

Filho, L.W. and D. Carpenter. 2006. Sustainability in the Australasian University Context. Berlin: Peter Lang.

Frisk, E. and K. Larson. 2011. Educating For Sustainability: Competencies & Practices for Transformative Action. Journal of Sustainability Education 2.

Gregory, K., Gurnell, A. and Pets, G. 2002. Restructuring physical geography. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers New Series 27: 136-154.

Huckle, J. 2002. Reconstructing Nature: Towards a Geographical Education for Sustainable Development. Geography 87:1, 64-72.

Kasimov, N.S., S.M. Malkhasova and E.P. Romanova. 2005. Environmental education for sustainable development in Russia. Journal of Geography in Higher Education 29:1, 49-59.

Kates, R. 2011. What Kind of Science is Sustainability Science? Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 108:49, 1449-1950.

Liu, L. 2011. Where in the world of sustainability Education is US Geography? Journal of Geography in Higher Education 35:2, 245-263.

Manning, E. 1990. Presidential address: Sustainable development, the challenge. The Canadian Geographer 34:4, 290-302.

Maragakis, A. and A. van den Dobblesteen. 2013. Higher Education: Features, Trends, and Needs in Relation to Sustainability. Journal of Sustainability Education 4.

Marsh, G. P. 1864. Man and Nature, or, Physical Geography as Modified by Human Action. New York: Charles Scribner.

McManus, P. 2004 Geography. In The Sustainability Curriculum: The Challenge For Higher Education, edited by J. Blewitt & C. Cullingford, 218-231. London: Earthscan Pubs.

Mulkey, S. 2012. Sustainability Science as a Foundation for Higher Education in the Environmental Century. Sustainability: The Journal of Record 5:6, 356-358.

National Council for Geographic Education (NCGE). 2014. “Geography for Life: National Geography Standards, Second Edition”, http://www.ncge.org/geography-for-life (accessed March 25, 2014).

National Council for Science and The Environment (NCSE). 2003. Recommendation for Education for a Sustainable and Secure Future. Washington, D.C.

NRC. 2010. Understanding the Changing Planet: Strategic Directions For The Geographical Sciences. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press.

Pattison, W.D. 1964. The Four Traditions of Geography. Journal of Geography 63:3, 211-216.

Pitman, A.J. 2005. On the role of Geography in Earth System Science. Geoforum 36:137-148.

Relph, E. 1997. Sense of Place. In 10 Geographic Ideas That Changes The World, ed. S. Hanson, 205-26. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

Robson, B.T. 1981. Geography and social science: The role of Patrick Geddes. In Geography, ideology and social concern, Oxford: Blackwell.

Rogers, Z., Bragg, E. 2012. The Power of Connection: Sustainable Lifestyles and Sense of Place. Ecopsychology 4:4, 307-318.

Saadation, O., K.B. Dola, E.I. Salleh, O.M. Tahir. 2011. Identifying Strengths and Weakness of Sustainable Higher Education Assessment Approaches. International Journal of Business and Social Science 2:3, 137-146.

Selby, D. 2006. The Firm and Shaky Ground of Education For Sustainable Development. Journal of Geography in Higher Education 30:2, 351-365.

Turner, B. L. 2002. Contested Identities: Human‐Environment Geography and Disciplinary Implications in a Restructuring Academy. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 92:1, 52-74.

Vincent, S. 2012. Trends in Interdisciplinary Environmental and Sustainability Education. Powerpoint talk presented at AASHE 2012 Conference October 14-17.

Wals, A.E.J., Jickling, B. 2002. ‘Sustainability’ in higher education: From doublethink and newspeak to critical thinking and meaningful learning. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education 3:3, 221-232.

Wheeler, G., Bergsman, K., Thumlert, C. 2008. Sustainable Design Project Teacher Manual. Olympia, WA: Office of the Superintendent of Public Instruction.

World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED). 1987. Our Common Future. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wright, T.S.A. 2004. Definitions and Frameworks for Environmental Sustainability in Higher Education. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education 3:3, 203-220.

Makayla J. Bonney in the Project Coordinator in the Indiana University Office of Sustainability. She has a B.S. and M.S. in Geography and Environmental Sustainability from Southern Illinois University. As an intern with National Geographic, Makayla studied the role of geoliteracy in introducing sustainability concepts in P-12 education.

Makayla J. Bonney in the Project Coordinator in the Indiana University Office of Sustainability. She has a B.S. and M.S. in Geography and Environmental Sustainability from Southern Illinois University. As an intern with National Geographic, Makayla studied the role of geoliteracy in introducing sustainability concepts in P-12 education.  Dr. Leslie A. Duram is a Professor in Geography and Environmental Resources and the Director of Environmental Studies at Southern Illinois University. She has published over 30 peer-reviewed journal articles and given more than 50 conference presentations and guest lectures that address two main environmental topics: local food and sustainability education.

Dr. Leslie A. Duram is a Professor in Geography and Environmental Resources and the Director of Environmental Studies at Southern Illinois University. She has published over 30 peer-reviewed journal articles and given more than 50 conference presentations and guest lectures that address two main environmental topics: local food and sustainability education.