An Ecology of Love: Women Farmers, Sense of Place, the Georgic Ethic, and Ecocentricity

Table of Contents: JSE March 2015 — Sustainability: What’s Love Got to Do with It?

PDF: Hintz JSE March 2015 Love Issue

Abstract: Women farmers in the U.S. are more likely than men to adopt more ecologically-based practices on their farms. In order for such practices to increase, it is relevant to understand how these women farmers learn the values and skills that shape their work. Place attachment (including the emotional connection to a locale and the intangible, felt meanings, values, and symbols) and place meaning (including personal values, socially and iteratively constructed values) seem to be important drivers of active care for place. These are mediated by ecological and social knowledge, experience, social relationships, and identity. If these factors are supportive rather than in tension with place attachment and place meaning, an active care for place can further develop the context for emotional bonds and the story of the locale. Regenerative farmers as well as others who work directly with the land are perhaps uniquely positioned to be leaders in the process of becoming part of a place. In this paper I summarize the literature about farmers’ relationship to place using a framework developed from the general sense of place literature. Finally, I discuss two aspects of this framework that emerged from research with 14 women farmers in Wisconsin and Minnesota: a georgic ethic and an ecocentric perspective: functional components of an ecology of love.

Keywords: Place attachment, place meaning, place-based learning, regenerative agriculture, women farmers, Midwestern agriculture, georgic ethic, ecocentricity, ecology of love

In teaching each other to love a place, it matters not only that we value it, but how we value it: the ecology, or functional system, of our values and our actions. Land-based people may offer important lessons for how this may be accomplished. In this paper I map two components of love for place among experienced women farmers practicing regenerative agriculture in the upper Midwest: the farmers’ georgic ethic and ecocentric perspectives.

In this place research I focus on female farmers because women in the U.S. tend to adopt more ecologically-based practices on their farms than do men (ATTRA News, 2006; Sachs, 1996; Trauger, 2001, 2004). Women’s greater concern for agriculturally related environmental issues also has been documented in Norway (Villa & Daugstad, 2007, p. 396). Understanding how the women in the current study related to their lands may offer important lessons for nurturing a functional love of place more widely.

Much room exists to widen understanding of the experiences and perspectives of female farmers. This paper is a version of one small portion of my 2012-2014 doctoral research into the lives of women farmers in the Upper Midwest. The women in this study created meaning around their work in order to become and remain regenerative farmers over the long term. The practice of regenerative agriculture for women engaged with it was connected with how each farmer situated herself in her farm ecology, how she considered her relationship to her communities, and what values enabled her to persist. Relationship to place was a central lens of the research, and love of land and community provided an important sustaining force. Literature around sense of place is extensive; this study integrates that research with the lived experience of land-based women.

Literature Review

Relationship to Place and Place Attachment

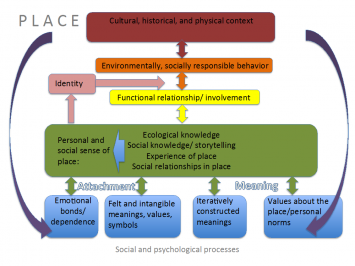

What are the functional components and synergies –the ecology – of a love of place? How is it that certain people feel a sense of responsibility for the quality of their place and a sense of kinship with it that then motivates environmentally and socially responsible behavior? Additionally, how is it that we can nurture more people to have those qualities? These three questions are at the heart of this consideration of relationship to place, specifically in the context of farmers practicing regenerative agriculture. Soul (1988) argued that arational, or affective, experiences and memories of nature – emotional, aesthetic, and spiritual – generate understanding and values. Rooted in the sensory-motor centers of the human brain and spread to the limbic system, these memories and experiences are more motivational than those created by knowledge, centered in the neocortex, alone. Indeed, Lockwood (1999) defines place (distinct from environment) as “a setting or landscape of profound meaning and connection to an individual by virtue of personal, direct experiences” (p. 368). Williams and Stewart (1998) summarized the sense of place literature by describing five dimensions to individuals’ sense of place: emotional bonds; felt and often intangible meanings, values, and symbols; values about a place; iteratively and socially constructed meanings; and cultural, historical and physical context. Emotional bonds and the felt and intangible meanings, values, and symbols are referred to elsewhere in the literature as place attachment (Kudryavtsev, Stedman, & Krasny, 2012). Iteratively and socially constructed meanings can include sociocultural, political, and economic dimensions of human life (Ardoin, 2006) often perpetuated through stories and the storytelling process (Huff, 2006; Somerville, 2007). All of these dimensions need to be understood from a systems perspective, that is, dynamically interrelated. Stokols and Shumaker (1981) and Vaske and Kobrin (2001) specifically found that a functional (active) relationship with place led to an emotional attachment of that place which further led to a range of environmentally responsible behavior. These core ideas, many of which are reviewed in Kudryavtsev, Stedman, and Krasny (2012), can be represented in a dynamic relationship as given in Figure 1:

Figure 1. Sense of Place Dimensions and Environmentally Responsible Behavior. This figure proposes dynamic relationships between some of the functional elements of sense of place derived from the literature.

Sense of place is connected to care for that place, as summarized in Kudryavtsev, Stedman, & Krasny (2012). However, much ambiguity remains around just how some of these dimensions support each other, and whether general and predictable patterns exist in individuals’ sense of place and resulting actions especially in an increasingly mobile culture (Ardoin, 2006). For example, an affective relationship to place that is not also coupled with ecological knowledge may not result in environmental behavior (Kudryavtsev, Stedman, & Krasny, 2012). Egoz, Bowring, and Perkins (2006) found that while conventional and organic farmers had a strong sense of place, the perceived disorder of the organic farms threatened the identity of the conventional farmers as traditional caretakers of the landscape and hard workers.

Despite the ambiguity surrounding the dimensions of sense of place, these facets provide a sufficient framework to begin to explore the literature on farmers’ relationship to place, and how that relationship might affect farmers’ practices. Farmers who practice ecologically-oriented agriculture as well as others who work directly with the land are perhaps uniquely positioned to be leaders in the process of becoming part of a place (Caniglia, 2010; Jackson, 2010, Lockwood, 1998) and protecting biodiversity (Lockwood, 1999). Mueller Worster and Abrams (2005), studying five farmers and five fisherfolk of New England, found three patterns in their sense of place: a sense of self emerging out of social relationships relating to particular ways of life, a sense of self developing from ecological understanding, and a deep, affective bond with place. These individuals showed a living experience of place that strongly informs their identities and the way that they talk about their work. In another study self-identity was positively correlated to farmers’ will to employ conservation practices that were not supported by government subsidies in the Netherlands (Lokhorst, Staats, van Dijk, van Dijk, & de Snoo, 2011).

Farmers’ Relationship to Place

As Williams and Stewart (1998) pointed out, very little of the scholarly literature on ecosystem management includes people as a natural part of the system. Similarly, in the literature of agroecology, almost none of it includes the farmer as part of the system. Farmer motivation and behavior is also not well explored in the social psychological literature (Lokhorst, Staats, van Dijk, van Dijk, & de Snoo, 2011). Cohen (2009) attributed some of this disconnect to the way the classical pastoral paradigm has so heavily influenced our sense of the land as well as agriculture and argued for a return to the georgic ethic, in which human labor deeply informs our relationship to the land, “lived cultural experience is not a sidebar to the discussion, but the basis from which the discussion can move forward” (p. 156). The pastoral paradigm casts us as observers of nature as a stage for contemplation, while we are active participants within the georgic worldview. Regenerative agriculture can play a reconciliatory role in the separation between people and place. Vos (2007) described sustainable agriculture as a middle landscape, mediating between the pastoral idea of wilderness and an environment fully constructed by humans.

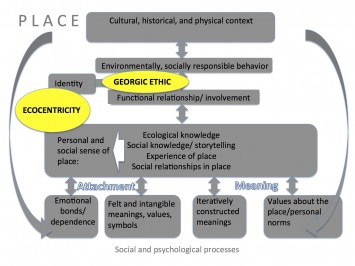

The current study focused on two areas of the framework proposed above: an ecocentric perspective and a georgic ethic:

Figure 2. A Georgic Ethic and Ecocentric Perspective within Sense of Place. This figure illustrates the foci of the current paper within the broader framework of a functional connection to place.

Methodology

In the current study I used an inductive (De Guerre & Taylor, 2004, LeCompte & Schensul, 1999) mixed methods approach (Knowles & Cole, 2008a) incorporating arts-informed research (Barone & Eisner, 2012; Finley, 2008; Leavy, 2009) and semi-structured ethnographic interviews of women farmers (Gubrium & Holstein, 2009; Polkinghorne, 1988; Reissman,1993). These methods together help provide a more holistic portrayal of the lives of the women farmers who participated in the research.

The research process consisted of four steps. Farmers completed a survey on farm ecology, economics, and social connectedness about each farm or site. This data provided the context (of regenerative agriculture) for a semi-structured interview with each of the 14 farmers in this study. My goals with the interview questions were: 1) to explore the farmer’s relationships to land and community; 2) to explore how the farmer developed from her experiences in relationship with people and land in the context of transformative learning; and 3) to identify the factors and relationships which sustained women farmers over lifelong work.

The farmer participants also developed several artistic pieces to help tell their stories. For this research project, I drew heavily on the philosophy of art and inquiry articulated by Finley (2008) as a means of transformation, emancipation, and elevating voices otherwise unheard. The goal with the art exercises was to move out of linguistically bounded reality and to create space for a more direct and holistic interpretation of each farmer’s experience of her land, work, and community (Knowles & Cole, 2008a). Each farmer was encouraged to create two arts-based projects following the first interview and reflect on their work. Eight farmers returned work to me, most sending two pieces.

I was able to return to nine farms for a site visit and open conversation. Often the conversation during the second visit occurred while doing a task together: weeding peppers, bunching garlic to dry, or potting up lettuce. This was also a time for the participants to ask me questions about my own farm and story as I had done with them. I also took photographs of the farms during this period. These materials were used to triangulate comments made by the farmers and arts-informed materials produced by the participants. As Ingold (2010) wrote, “…these figments are but outward, sensible forms that give shape to the inner generative impulse that is life itself” (p. 17). By visiting the farmers’ places, I absorbed a holistic sense of who they were, experiencing what de Certeau (1984) calls spatial stories. The walking ethnography of the farm tour provided an important intersection between traditional ethnographic tools and art as a method in my research (Pink, Hubbard, O’Neill, & Radley, 2010).

Participant population.

This study involved 14 women farmers in Wisconsin and Minnesota whose farms are exemplars of ecological agriculture, viable businesses, and civic interconnection. Farms that exemplify a wide range of approaches, from annual vegetable cropping to animal husbandry to Permaculture were chosen. All of the farmers who participated in the study have been practicing farming for at least a decade and generally much longer by their report. Choosing this level of experience among the farmers allowed for the sharing of rich life histories.

Represented areas in the study included Minnesota’s North Shore, the south shore of Lake Superior in Wisconsin, south-central Wisconsin, western Wisconsin, the Twin Cities area, and western Minnesota. Of the 14 participants, two operated dairy farms (goats on one farm and sheep and cows on the other), two raised rotationally-grazed beef, one raised sheep for wool and meat, and nine raised vegetables. Of the nine who raised vegetables, only one did not run a CSA (among other outlets). Only one farmer claimed some minority ancestry. Participant ages ranged from mid-40s to early 70s. Farmers had between 10 and 41 years of practice at their craft, most with at least two decades of experience. Farm size varied enormously from a small flock of sheep to a CSA with more than a thousand members. Soil types and topography also were maximally diverse from clay to, as one farmer put it, beach sand, and flat prairie land to bedrock and rolling hills along Minnesota’s North Shore. Four of the participants farmed solo; either they did not have a partner, or the partner did not participate in the farm. The other ten farmers farmed with their partner to a greater or lesser extent. This range of enterprises and personal circumstances provided a rich group of participants for the study.

Results

Because the actual and profound experiences of the women in this study ground the theory of place in the farmers’ dynamic interrelationships with their farms, and because the farmers are essentially co-creators of this study, I privilege their words in this section of the paper. Love was evident in the way the farmers discussed their relationship with the land. Carol described her attraction to a small town in Minnesota, “I just kind of had it in my bones” (Carol, personal communication, February 22, 2014). This sense of care was true regardless of the years spent on the farm – one farmer had farmed on four different pieces of land – or ownership: one farmer had always managed farms she did not own, and one farmer had rented many plots of land in addition to her home farm.

Each woman’s attachment to her farm had a specific anatomy: instances, views, smells, tastes, and the meanings that overlaid all of it: the ecology of love. Landis described some of the details that made up her delight in her farm.

I think every year we tap maple, trees for syrup making, some of my best memories are that first ting in the bucket. That begins another season, another harvest year. That to me is the first of the year, so I really like that. Just a million little things of just laughing with the crew or just playing with our dogs or sitting down after racing before a freeze and being soaking wet and it freezing and then just sitting down to a bowl or soup or something like that, and just being like ahh. (Landis, personal communication, October 2, 2014)

Several of the farmers described their connection to their land in spiritual terms.

The animals on the land, I just love looking out that window there when I’m washing dishes and seeing the goats and sheep just out pasturing. Just what it provides for us. Is my connection, I love it here. I don’t know if I can fully explain why, but it’s just so peaceful to me. It’s a lot of hard work in the summer when I am full speed ahead there’s days I don’t take the time to look out the window or look out when I’m out there working and say, “Wow this is really beautiful.” Because you’re just so busy. But, I just love being here. It’s got a spirit about it. (Diana, personal communication, December 10, 2013)

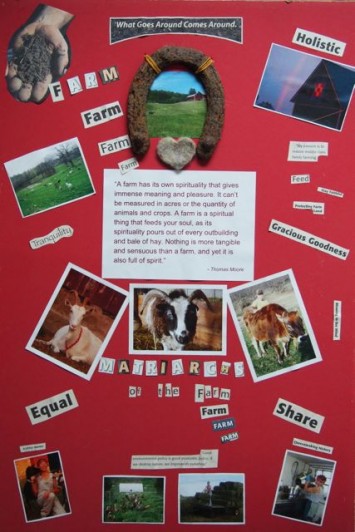

Not all of the farmers could put words to that connection. Instead it was often the spaces between the words as we were talking or walking the farm that most eloquently conveyed their feeling about it. However, Diana’s choice of quote in her collage speaks directly to that spirit.

Figure 3. Diana’s Collage. This figure illustrates a visual reflection of Diana’s experience as a farmer.

Janet practiced biodynamic agriculture on her farm, which has a strong spiritual component, as well as a developed holistic approach. Janet had managed a number of farms for different landholders over her career. Her connection to land transcended ownership;

I love the land, I have a love relationship with the land. I have always loved every place that I’ve been equally. It’s and they all have been very different places. What I know too is I want to leave it better than I found it, and it’s as simple as that. (Janet, personal communication, December 23, 2014)

Many farmers in the heavily agricultural areas of Wisconsin and Minnesota rent land from each other as inheritance, sale, and consolidation have made a patchwork of the landscape and as the cost of owning land has grown more prohibitive. Dela’s care of rented land persisted despite a cycle of improving the land to the point that she made it attractive to competing renters.

Because we outgrew this spot, which is still always our main garden, and everything that needs real close attention is here because I can see it. And then second at our lease now, but before they were here, we would rent little parcels that big machinery couldn’t get into from different farms or that had lain fallow for a while. And some of those fields were good, and some were terrible. If they’d been fallow they were fine. If they had had conventional farming going on, the soil would usually be not proper, you know. It would be compacted. It would be pale, and there would often be no worms or bugs. And we would haul manure and do all the stuff that we could to quickly fix what can’t be quickly fixed. And so it was very difficult to grow on some of those parcels…. we’d rent these little funny corners and the farmers renting the big part would go oh. They can grow in there, and we’d inevitably lose it. And the trees would go down, and they would, somebody would offer more money. So, that happened a lot over the years. We’d work someplace, and you’d have to work a few years and get it better, and then lose it. (Dela, personal communication, December 10, 2014)

Even though long-term prospects with a given piece of rented land were tenuous, Dela still treated each place with respect. Her value of the relationship and the overall health of the land stood in contrast to the practices around her of using the land solely as a resource to be mined. The respect that Dela showed also was in evidence from the other farmers in this study. Awe was a component of the love that many of the women felt for their land.

I get that there’s a certain splendid mystery to soil that our human noggins want to believe that we have understood completely but we have not. There are things that are happening between plant root and soil that we are still learning. (Carol, personal communication, February 22, 2014)

The women’s attachment to place was a strong motivator for their persistence. Their love was a value that seemed mobile with a transition to different land and regardless of ownership. With this love also came an acceptance of loss for a number of the farmers, who either moved farms, or lost rented land.

“I am part of the farm.”

Even as the women experienced a sense of empowerment through their farming practice, they believed that their success arose in part from their relationship to their land, which involved a certain humility. All viewed themselves as a part of the larger ecosystem, and spoke eloquently about that connection.

I think one of the things I learned is how to be whole in a place. And to nurture it in a way that sustains me so that I can help sustain it and that is a precious cycle of resilience and recovery and tenacity and delight. (Audrey, personal communication, February 5, 2014)

The sense of connectedness ultimately could blur the boundaries between self and farm. Audrey phrased it pithily. “I don’t say that we work with nature but we are nature” (Audrey, personal communication, February 5, 2014).

Where the farmer ended and the rest of nature began was often hard to pinpoint, and often hard to articulate. Lise echoed Audrey’s sense of symbiosis.

It feeds me in a way more than just the physical food that comes out of it. But I think the fact that I have a relationship to it through farming with it intensifies that. It’s different than just living in a cabin in the woods. I think that I feel both responsible to it, to be taking care of it because it’s feeding me, but it just feels like it’s giving back to me as well in a way that’s different than just a yeah, just friends who have beautiful houses in the woods, and they love their places in the woods but I just, there’s a different connection there that is a mutual kind of thing. (Lise, personal communication, January 28, 2014)

This deep, active relationship with the land was based on shared productivity and something more. Not everyone in the farmers’ lives understood this connection or its cycles.

I have tried to talk to people about how the land is like the third party in the relationship, and they don’t understand, because it’s like this place is as important to me as another human being would be. How to take care of it and how to be connected with it, and the fact that it’s hard to leave for long periods of time, because well, now there’s greenhouses to worry about in the winter. There’s this or that, but you don’t just go away for chunks of time, because you’ve got plants to tend or buildings, and it is a relationship. It is a partner in your life. A lot of people don’t like that. They find it… they want to be in a relationship with only two parties, not the third. They also don’t understand that you can’t turn it off on the weekend, because you’re living right here. You see things. (Tricia, personal communication, December 23, 2013)

Like many human long-term relationships, the partners in some ways grow together over time and shape each other. Landis described this melding in detailed physical terms.

There’s so many ways you are connected to your farm, because so I literally eat my farm. So the plants that grow there. I get my sustenance from them, so I’m actually ingesting a little bit of my farm, and slowly those cells are being replaced, and so I am of that soil literally. Figuratively, you accumulate a certain knowledge like we talked about that starts becoming part of you old memories, or your memories in general. I can remember where my daughter took her first steps now, and things oh, remember the time. So that all gets part of that connecting to your land. I think when you work everyday at the same place, and you wear down paths, and you just become part of that farm. You are physically part, I can hardly even say it, but you are literally in so many, you know the paths meander because your hips meander when you walk. That it looks like how you walk, and the design of where buildings go or where fields go reflect your aesthetics or– It’s all those connections. I think a farmer ultimately is no different than the toads or the trees. I mean it’s a part of that farm. You’re not the overseer, you’re just a part of. Yeah. That’s how I think about it at least. (Landis, personal communication, October 2, 2013)

This connection, in many of the farmer’s minds, meant giving up an illusion of control and acquiescing to the farm’s rhythms.

What I really noticed is that me and the farm are not separate, and not having grown up on a farm, I didn’t know this, but when you are farming it is not a job it is a lifestyle. So, having moved here and started this farm I was making a lifestyle change. So, I was making a really big change when I started farming, and I think just learning that about myself, and total acceptance of the farm, me and the farm are sort of like this unit that work together. And I had to actually really let go of trying to be in control of. Okay, this is what I need to do now or this is what I need to do now. No this is what you are going to do when you can do it, because this is what the farm needs now because it is a farm. And it needs certain things at certain times. (Barb, personal communication, February 27, 2014)

The farm’s cycles were respected, which did not always align with human economics. Working in partnership with natural systems, all the farmers in this project understood the need for patience, diversity on the farm, and diverse income streams.

I think the hardest thing I had to explain to other people why farming you can be successful and not make any money at it, is that you’re dealing with biological systems that always have their own– They’re not working in a test tube. They’re growing in a very diverse, and there are so many variables that come to play, that your role as a farmer is really just to kind of catalyze that so that those plants grow. (Landis, personal communication, October 2, 2014)

Hard work.

The farmers took pride in the hard work of farming that was part of their life. Rather than acting primarily as one of the challenges to persistence, at least some of the time it seemed to energize or give purpose to the farmers’ practice over the long term. The element of hard work may weed out some would-be farmers early in the learning curve; the farmers in this study valued being physically active and challenged; at least up to a point. A number of farmers reflected on how hard work was underestimated in a variety of ways. For Landis, a successful farm came down to the simple need to put the effort into it. “There’s no secret formulas really, just hard work and just keeping at it” (Landis, personal communication, October 2, 2013).

Julie, a retiree who came from a professional urban life, commented on the perception in her earlier social circles that working hard was a sign of backwardness in some way.

And there’s another component of this that’s about work, and what does it mean to work. A lot of people say why do you want to do all that work. My question is why not. If we can physically do it and it’s important, it’s our farm. They’re our animals. Why wouldn’t we want to do it? But there’s that attitude about work, and especially getting your hands dirty. Because we’re well educated people, “Oh you shouldn’t have to do that.” Why not? It’s the 64,000 dollar question to me, it’s like, well where’d you get that attitude. I was never into playing golf; it just wasn’t my thing. For some folks, well that’s fine, but it is, there an attitude about work. We were just able to make that transition, to see that we could do it. It was kind of this big challenge. It’s like, okay, we can do this. (Julie, personal communication, January 25, 2014)

Julie went on to comment wryly that she and her husband are not prone to the sleeping problems of her urban friends. For Julie, the work lent her purpose and kept her physically agile. Some of the farmers commented on loving their work.

We have more, I think, people come and go in the CSA world because it’s physically harder than they thought. And I see that with the interns too. They have a very idyllic picture of what they are going to be doing, and you know, the baby lambs are cute but you’ve got to shovel the shit. So, it’s, the reality sometimes is more than people thought. And, but I don’t know, I think either you really love that or not. And I really love it. (Dela, personal communication, December 10, 2014)

At times during the early growth of the farm, Kristina juggled a full-time professorship, home-schooling her daughter, and farming.

In the long term, I think you really truly have to love what you do, because it is so much work. Evaluating and looking at the reasons for why you’re doing it, and making sure that those reasons are the right reasons. Otherwise, you can’t make it, because it is too hard physically and also at certain times of the year in terms of your time and your balance with things. (Kristina, personal communication, December 20, 2014)

For Tricia, the value of hard work was learned from her upbringing.

What it set me up for, the quality that came from my family was the ability to understand what it means to work that hard. The understanding that you spend most of your times from spring getting ready for the next winter. Just this determined stubborn streak of just hanging in there. I think without that background from my family I would have given up a long time ago, because there’s a lot easier ways to make a living. (Tricia, personal communication, December 23, 2013)

Even though the farmers enjoyed the work, it was a fine balance between motivating and challenging. Though Lise felt satisfied with her life, she wondered if she would have encouraged her sons into the same occupation if they had been interested.

So I do feel, it’s a little hard when I, when I see these idealistic young people. I’m so glad to see them, like at conferences and stuff, all these tracks now for new farmers, and I’m like, oh you poor things. And I hate thinking that way though, because I suppose people thought that with us too, and I’m happy enough what we’re doing. So I don’t say anything. So, but it’s kind of hard to see that and to realize how what a difficult life they are choosing in many ways, fulfilling but difficult. (Lise, personal communication, January 28, 2014)

Still, Landis articulated some of the rewards of such hard labor.

I really like the physicality of it. I am not a good, I have a hard time sitting still, and it that breathing deep and feeling really strong is feels really good, even as I’m aging and feeling more creaky. I also really like the seasonality of it, and though we do a winter CSA too and do winter marketing, there’s a certain downside, and I like that mental break and physical break, but I also then like the intensity of summer. I love that, I used to commercial fish in Alaska, and there was, you sat around waiting doing absolutely nothing, and then all of a sudden you might work 48, 56 hours without any sleep because you just fishing. That kind of adrenaline intense, I’m making money, you get some of that in farming too. Now you’re kind of running on empty, but man, this is when the harvest is coming in, and you’re just racing against snow. It’s very exciting, and the comradery when the group of us are hauling in and you’re like whoa look at all of this. It’s just great. Those are just, I didn’t know that was what it was, but that’s fun. That’s really fun. (Landis, personal communication, October 2, 2013)

As Caniglia (2010) found with women ranchers, commitment to the hard work of the lifestyle for rewards that are more about community, self-reliance, and a connection to the land separates these successful women farmers from the idealized portrayal of the pastoral life that has crept into the media in the last several years. To be sure, the work is daunting, and the women’s love of their land and sense of community with it, their ecology of love, was one aspect that helped them to persist.

Discussion

The farmers understood their connection with their land to be a participatory relationship to which they were committed. This ecocentric perspective, or living systems viewpoint, arose directly from their georgic ethic; an important consideration for the broader conservation movement. The women farmers’ georgic ethic and ecocentric perspective provided them a transformative story to persist in their work, one that stood in contrast to the pastoral ethic that undergirds much of the environmental movement (Oates, 2003). The mutual, active, and communal relationship that the women had with their land was central to the narrative they told me.

A georgic ethic and reciprocity.

Cohen (2009) provided a succinct outline of the importance of the georgic ethic to understand new trends in valuing local knowledge, experiential learning, and sense of place in the study of agriculture. For the farmers in the current research, their mutual relationship to the land through their work provided them with a deep sense of reciprocity and ongoing support. Their ecology of love was not the passive appreciation and contemplation of a landscape outside of, though spiritually connected to, themselves, as a pastoral ethic might provide. Instead, they knew their land and cared about it and saw themselves as a part of it because they worked with it and knew their lives depended on its wellbeing. This ethic is also a central tenet of ecofeminism (MacGregor, 2006). Interestingly, this understanding of relationship with their land remained consistent whether the farmer operated mostly by hand labor or with the use of several tractors and a large field crew, though the ethic appeared somewhat more detailed for those farmers who spent more time working by hand. Lise explored many of the facets of this dynamic, from a sense of nurturing to a spiritual foundation.

I feel, the cliffs up there– it’s a spiritual thing to me. It feeds me in a way more than just the physical food that comes out of it. But I think the fact that I have a relationship to it through farming with it intensifies that. It’s different than just living in a cabin in the woods. I think that I feel both responsible to it, to be taking care of it because it’s feeding me, but it just feels like it’s giving back to me as well in a way that’s different than just a yeah, just friends who have beautiful houses in the woods, and they love their places in the woods but I just, there’s a different connection there that is a mutual kind of thing. As it’s, as I think about it more, as I’ve gotten older, I think about the Native Americans and I probably can’t relate completely, but I can begin to relate to the incredible, when they were removed from their land, the incredible break that was in their psyche to be removed from their place which I probably cannot even imagine. It was even more so with a culture like that. I feel like that must be it. It’s something that’s attached psychically, in my psyche that it would be hard to leave. (Lise, personal communication, January 28, 2014)

Lise’s comment about an indigenous connection is one we will return to momentarily in the section on ecocentricity. Barb, who operated a large vegetable CSA with her family, tracked her farm health as much by the quality of her wetlands as by her crop production. She learned a partnership with her land through her work.

What I really noticed is that me and the farm are not separate, and not having grown up on a farm, I didn’t know this, but when you are farming it is not a job it is a lifestyle. So, having moved here and started this farm I was making a lifestyle change. So, I was making a really big change when I started farming, and I think just learning that about myself, and total acceptance of the farm, me and the farm are sort of like this unit that work together. And I had to actually really let go of trying to be in control of. Okay, this is what I need to do now or this is what I need to do now. No this is what you are going to do when you can do it, because this is what the farm needs now because it is a farm. And it needs certain things at certain times. (Barb, personal communication, February 27, 2014)

Interestingly, in The Georgics, Virgil meant to inspire his contemporaries back to agrarianism and away from their increasing socioeconomic culture of war (Cohen, 2009). The women of this study model the same exhortation for contemporary times; eschewing the agrochemical byproducts of the Second World War and operating from power derived from interdependence rather than domination. The women farmers’ stories and perspectives are an important contribution to the popularly male-dominated discourse on the value of human labor connecting us to the earth (e.g. Berry, 2002; Jackson, 2010).

Ecocentricity.

Building on Leopold’s (1949) work, Caniglia (2010), in her study of women ranchers, defined ecocentrism as “a philosophy based on the whole environment (human and other than human ecosphere) that does not give preference of perspective, values, or rights to any one organism” (p. 297-298). As a part of their narrative, I asked the women in this project to provide artwork that described their experience of farming. As with the pilot project to this study, the farmers did not portray themselves centrally in their farm system. Of the visual pieces returned to me, only four contained human figures, and none of them were positioned in the middle of the piece. In their interviews, the farmers talked about themselves as a part of their agroecosystem, and for them this led to a certain humility approaching their work with their land. One might contrast this perspective with any number of pesticide names that bespeak a vastly different world-view: for example, Terminator technology, Vanquish, Certainty, and Confront.

In their connection to place, the perspectives of these women farmers more closely resemble an indigenous world-view (Martinez, 2008, 2010), including a sense of the rights of future generations, seasonal cycles, interconnectedness, nature as a relation, and reciprocity.

And so we have a pretty well defined goal about what we want the quality of our lives to be like. And we have had the discussion not just between the two of us but engaged our kids and other family members, which has been good in the long term but hard when we were doing it, but it still was good to have, you know. Talking about quality of life and what kind of production would support that and what kind of landscape, what kind of… how what our understanding is – this is pretty spelled out – by how ecosystem processes need to function long into the future to be able to support production for people who are not born yet. And we tend to take that long view and it is. (Audrey, personal communication, February 5, 2014)

The women’s stories offer important lessons of coming home in a mobile and generationally immigrant culture.

And I was sitting amongst this pile of boxes, and it was pouring rain outside, and I was, I had taken the day off of work, because I always take the day off on my birthday, not since I have been farming, but back in the day when I had off-farm jobs it was like, it was a day, my day, so I was sitting looking out the window, and I said, “I’m home. I’m home.” And it was you know, I was just, it was just this really deep feeling that I found inside of me. It’s like, what does that mean? I don’t know what that meant. That I had found someplace to be…. We had only been here for ten days but there was something about, you know, it’s just like I’m settled. It’s like okay, this is where I am supposed to be. (Barb, personal communication, February 27, 2014)

This ecocentric understanding was integral to the lives of the women described here. Though their early childhood or college experiences planted the seeds for this understanding, the farmers also developed this relational knowledge through experiential learning by working with the land.

Conclusion

Place attachment (including the emotional connection to a locale and the intangible, felt meanings, values, and symbols) and place meaning (including personal values, socially and iteratively constructed values) seem to be an important driver of an active care for place. These are mediated by ecological and social knowledge, experience, social relationships, and identity. If these factors are supportive rather than in tension with place attachment and place meaning, than an active care for place can further develop the context for emotional bonds and the story of the locale. The women farmers practicing regenerative agriculture in this study are an important example of an iterative relationship to place that also shapes human identity as it nurtures the health of the land: an ecology of love. This paper explores two facets critical to the farmers’ functional relationship to place: a georgic ethic and an ecocentric perspective. Much more research into the experiences of women farmers can help inform the healthy reconnection of people to place.

Bibliography

Ardoin, N.M. (2006). Toward an interdisciplinary understanding of place: Lessons for environmental education. Canadian Journal of Environmental Education, 11(1), 112–126.

ATTRA News (2006). Women in sustainable agriculture. ATTRA News, 14(2). Retrieved from: https://attra.ncat.org/newsletter/attranews_0306.html

Barone, T. & Eisner, E. W. (2012.) Arts based research. Los Angeles: Sage.

Berry, W. (2002). The art of the commonplace: The agrarian essays of Wendell Berry. Berkley, CA: Counterpoint.

Caniglia, N. C. (2010). Voices for the land: Women ranchers’ sense of place and role in passing on knowledge, values, and wisdom. (Doctoral dissertation). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses: The Humanities and Social Sciences Collection. (UMI No. 3472534)

Cohen, B R. (2009). The once and future georgic: agricultural practice, environmental knowledge, and the place for an ethic of experience. Agriculture and Human Values, 26, 153-165. doi:10.1007/s104460-008-9172-7

de Certeau, M. (1984). The practice of everyday life. (Steven F. Rendall, Trans.) Berkley, CA: University of California Press.

De Guerre, D. W. & Taylor, M. (2004). Graduate leadership education in a socio-ecological perspective: Working at the paradigmatic interface. In: E. O’Sullivan, & M. Taylor (Eds.). Learning toward an Ecological Consciousness (pp. 5-23). New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Egoz, S., Bowring, J., & Perkins, H.C. (2006). Making a ‘mess’ in the countryside: Organic farming and the threats to sense of place. Landscape Journal, 25, 54-66. doi:10.3368/lj.25.1.54

Finley, S. (2008). Arts-based research. In: J. G. Knowles & A. L. Cole. (2008). Handbook of the arts in qualitative research. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Gubrium, J. F., & Holstein, J. A. (2009). Analyzing narrative reality. Los Angeles: Sage.

Huff, L. A. (2006). Sacred sustenance: Maize, storytelling, and a Maya sense of place. Journal of Latin American Geography, 5(1), 79-96. doi:10.1353/lag.2006.0006

Ingold, T. (2010). Ways of mind-walking: Reading, writing, painting. Visual Studies, 25(1), 15-23. doi:10/1080/14725861003606712

Jackson, W. (2010). Consulting the genius of the place: An ecological approach to a new agriculture. Berkeley, CA: Counterpoint.

Knowles, J. G., & Cole, A. L. (2008). Handbook of the arts in qualitative research: Perspectives, methodologies, examples, and issues. Los Angeles: SAGE.

Kudryavtsev, A., Stedman, R. C., & Krasny, M. E. (2012). Sense of place in environmental education. Environmental Education Research, 18(2), 229-250. doi:10.1080/135046622.2011.609615

Leavy, P. (2009). Method meets art: Arts-based research practice. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

LeCompte, M. D., & Schensul, J. J. (1999). Analyzing & interpreting ethnographic data. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press.

Leopold, A. (1966). A sand county almanac. New York, NY: Ballantine. (Original work published 1949)

Lockwood, J. A. (1998). The intent and implementation of the ESA: A matter of scale. In J. Shogren (Ed.), Endangered species and private property (pp. 70-91). Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

Lockwood, J. A. (1999). Agriculture and biodiversity: Finding our place in this world. Agriculture and Human Values 16(4): 365-379. doi:10.1023/A:1007699717401

Lokhorst, A. M., Staats, H., van Dijk, J., van Dijk, E., & de Snoo, G. (2011). What’s in it for me? Motivational differences between farmers’ subsidized and non-subsidized conservation practices. Applied Psychology: An international review, 60(3), 337-353. doi:10.1111/j.1464-0597.2011.00438.x

MacGregor, S. (2006). Beyond mothering earth: Ecological citizenship and the politics of care. Vancouver, Canada: UBC Press.

Martinez, D. (2008). Native perspectives on sustainability. Retrieved from : http://www.nativeperspectives.net/Transcripts/Dennis_Martinez_interview.pdf

Martinez, D. (2010) The value of indigenous ways of knowing to western science and environmental sustainability. Journal of Sustainability Education, May 9th, 2010. Retrieved from: journalofsustainabilityeducation.org

Mueller Worster, A., & Abrams, E. (2005). Sense of place among New England commercial fishermen and organic farmers: implications for socially constructed environmental education. Environmental Education Research, 11(5), 525-535. doi:10.1080/13504620500169676

Oates, D. (2003). Paradise wild: reimagining American nature. Corvallis, OR: Oregon State University.

Pink, S., Hubbard, P., O’Neill, M., & Radley, A. Walking across disciplines: from ethnography to arts practice. Visual studies, 25(1), 1-7.

Polkinghorne, D. E. (1988). Narrative knowing and the human sciences. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Riessman, C. K. (1993). Narrative analysis. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Sachs, C. (1996). Gendered fields: Rural women, agriculture, and environment. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Somerville, M. (2007). Place literacies. Australian Journal of Language and Literacy, 30(2), 149-164.

Soul, M. E. (1988). Mind in the biosphere; Mind of the biosphere. In: E. O. Wilson (Ed.), Biodiversity (pp. 465-469). Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press.

Stokols, D., & Shumaker, S. A. (1981). People in places: A transactional view of settings. In J. H. Harvey (Ed.), Cognition, social behavior, and the environment (pp. 441-488). Hillsdale, NJ: Eribaum.

Trauger, A. (2001). Women farms in Minnesota and the post-productivist transition. The Great Lakes Geographer, 8(2), 53-66.

Trauger, A. (2004). ‘Because they can do the work’: Women farmers in sustainable agriculture in Pennsylvania, USA. Gender, Place & Culture: A Journal of Feminist Geography, 11(2), 289-307. doi:10.1080/0966369042000218491

Vaske, J. J., & Kobrin, K. C. (2001). Place attachment and environmentally responsible behavior. The Journal of Environmental Education, 32(4), 16-21. doi:10.1080/00958960109598658

Villa, M., & Daugstad, K. (2007). Summer farmers: Gender discourses in new arenas. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 38(3), 395-408.

Vos, T. (2007). Organic farming and the socioecological imaginary: The philosophy and practice of stewardship in the middle landscape (Doctoral dissertation, University of California, Santa Cruz). Available from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses.

Williams, D.R., & Stewart, S.I. (1998). Sense of place: An elusive concept that is finding a home in ecosystem management. Journal of Forestry, 96(5), 18-23.

Clare Hintz is the editor in chief of the Journal of Sustainability Education. Clare has a Ph.D. in Sustainability Education with a focus on Regenerative Agriculture. She founded a liberal arts program in sustainable agriculture at Northland College in Ashland, WI. She served as the college's sustainability coordinator for many years before leaving to become a full-time farmer and community educator. Clare has been teaching sustainable agriculture and permaculture since 1998, and has additionally developed curricula for the University of Wisconsin, River Falls, University of Minnesota, Duluth, and Prescott College. She is a permaculture consultant in the Midwest, U.S. Her research focuses on arts-informed inquiry, regenerative agriculture, place, and ecofeminism. You can see more of her work at www.elsewherefarm.com.

Clare Hintz is the editor in chief of the Journal of Sustainability Education. Clare has a Ph.D. in Sustainability Education with a focus on Regenerative Agriculture. She founded a liberal arts program in sustainable agriculture at Northland College in Ashland, WI. She served as the college's sustainability coordinator for many years before leaving to become a full-time farmer and community educator. Clare has been teaching sustainable agriculture and permaculture since 1998, and has additionally developed curricula for the University of Wisconsin, River Falls, University of Minnesota, Duluth, and Prescott College. She is a permaculture consultant in the Midwest, U.S. Her research focuses on arts-informed inquiry, regenerative agriculture, place, and ecofeminism. You can see more of her work at www.elsewherefarm.com.