Upadhyaya JSE April 2019 General Issue PDF [1]

Link to the JSE April 2019 General Issue Table of Contents [2]

Abstract: As noted by a growing number of marketing scholars, the importance of educating marketing students on sustainability should be an important objective for marketing educators and business schools alike. The focus of sustainability-based marketing education is on the greater good of the environment and society, while adjusting internal and related external processes to sustainability principles. In this conceptual paper, we adopt a broadened definition of sustainability distinct from the narrow understanding of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) adopted by the business world in general and make recommendations for using this broadened definition to reframe marketing curricula and pedagogy. We give specific examples of assignments and pedagogical approaches for four core marketing courses as well as four marketing electives. By doing so, we hope to foster a new marketing mindset and a new generation of marketing practitioners who embrace, internalize, and practice sustainability holistically.

Keywords: sustainability, marketing curriculum, marketing pedagogy, active learning, integrated learning

Introduction

In 1987, the United Nation’s Brundtland Report brought the concept of sustainable development to mainstream attention and made it clear that our pre-existing approach to economic development, our systems of production, our marketing practices, and our patterns of consumption were environmentally and socially unsustainable (United Nations, 1987). Continuing concerns about the environmental and social impact of unrestricted economic growth, especially as it relates to the complex issue of climate change, now make the initial message of the Brundtland Report even more urgent. Although slow to respond to this global crisis, business schools have recently acknowledged this call to action. AACSB, the Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business International, now officially advocates – but does not yet mandate – the integration of ethics, corporate social responsibility, and sustainability in all business disciplines. In this context, the AACSB standards to date allow this “combined definition” to be limited to a single, stand-alone course and this is typically how most business schools interpret compliance (AACSB International, 2017; Weybrecht, 2015).

In contrast to other business disciplines, marketing’s focus on consumers and the external marketplace make it uniquely positioned to embrace and internalize sustainability as a framework for scholarship, practice, and curricular integration. However, marketing as a discipline and practice has been slow to evolve (Lim, 2015; Too and Bajracharya, 2013). Changing our production and consumption systems cannot be achieved without changing our marketing mindset and forever abandoning the assumption that the issue at the root of marketing activity is how to produce more products for even more people.

As noted by a growing number of marketing scholars, the importance of educating marketing students on sustainability should be an important objective for marketing educators and business schools alike (Borin and Metcalf, 2010; Bridges and Wilhelm, 2008; Germano et al., 2015; Mather et al., 2011; Stewart, 2010; Üçok Hughes, 2015; Wilhelm, 2008). According to Martin and Schouten (2012), the focus of sustainability-based marketing education is on the greater good of the environment and society, while adjusting internal and related external processes to sustainability principles. In this conceptual paper, we adopt a broadened definition of sustainability distinct from the narrow understanding of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) adopted by the business world in general. We then make recommendations for using this broadened definition to reframe marketing curricula and pedagogy. And, finally, we give specific examples of assignments and pedagogical approaches for four core marketing courses and four marketing electives. By doing so, we hope to foster a new marketing mindset and a new generation of marketing practitioners who embrace, internalize, and practice sustainability holistically.

A Broadened Definition of Sustainability

When defining sustainability, a narrow definition that focuses primarily upon the impact of production and consumption on the natural environment is widespread. However, the Brundtland Report (1987) proposed a broader framework for sustainability that considers not only ecological concerns, but also economic and social justice concerns (Bridges and Wilhelm, 2008; United Nations, 1987). The report defines sustainability as “…development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” (Brundtland Report, 1987). While published over thirty years ago, the Brundtland Report (1987) remains extraordinarily relevant for defining the framework for sustainable (and unsustainable) development. For example, the principal outcomes of the report served as the intellectual foundation for the Earth Summit in 1992, the Paris Climate Agreement in 2015, and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (currently the leading global framework for international cooperation on sustainable development) (www.iisd.org [3]).

Business schools typically take a surface-level approach to address sustainability by offering a single ethics course as part of the core curriculum of undergraduate and graduate business degree programs. Such courses typically provide a basic introduction to ethics and corporate social responsibility (CSR) from a managerial perspective that primarily seeks to satisfy the short-term interests of company stakeholders. A broader framework for sustainability that comprehensively considers ecological, economic, and social issues is not addressed as such issues are deemed external to the goals of the corporation and its stakeholders. Nonetheless, there have been growing calls for inclusion of well-developed sustainability-related courses in the core curriculum (Burns, 2011; Jabbour, 2010; Stubbs and Cocklin, 2008; Stubbs and Schapper, 2011) as well as the integration of sustainability principles programs at all levels of higher education institutions (Stewart, 2010). Walter and Sharyan (2015) emphasize the role of sustainability education in training business students to become aware of “their roles as both citizens and managers with respect to contributing toward healthy and sustainable communities” (p. 22). The goal of sustainability-oriented marketing education is to highlight the importance of a resource-effective approach in undertaking internal operations while ensuring societal well-being (Martin and Schouten, 2012).

A narrow perspective on sustainability focused only on business ethics and corporate social responsibility (CSR) presents a similar challenge within corporations. Global interests in CSR and sustainability “stem largely from the concerns held by many in every society about the real and perceived effects of rapid globalization and development issues” (Eweje, 2014, p. 4). However, companies adopting CSR policies often confound the concept with sustainability. This creates a dilemma because CSR and sustainability have different underlying principles. While CSR focuses on the ethical stance of the company to achieve a balance between the needs and expectations of its various stakeholders; sustainability principles move beyond stakeholders’ interests and focus on longer-term, intergenerational social, economic, and ecological impacts.

The quick fixes provided by CSR initiatives utilize existing resources in the creation of alternatives that may be at best solutions in the short run, but lead to irreversible adverse consequences in the long run. For instance, Unilever has shared its commitment to sustainability while it has been at the center of environmental (e.g. Mercury exposure of workers in India), ad campaign (e.g. Dove ad considered racist by some consumers), and labor rights (e.g. sexual harassment of workers in South African workers) controversies (Unilever-Sustainable Living, 2017; Astor, 2017; Lakshmi, 2016; Roff, 2017).

There are companies that demonstrate excellent examples of how sustainability can be easily and effectively integrated into their business models to maximize both their financial and social goals. For instance, Siemens aligns its business vision, mission, and goals with United Nation’s 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (Siemens-Practicing Sustainability, 2017). Their business model serves as a benchmark for companies aspiring to adopt a comprehensive sustainability framework. This model is definitely part of a positive trend in marketing practice – the adoption and implementation of sustainability principles in the crafting of business visions and missions rather than simply treating sustainability as a moral or ethical decision.

Demarketing (Levy and Kotler, 1971) is an emerging practice among sustainability-driven companies that involves an intentional reduction of the demand for a product to strike a balance between overall financial goals and sustainability-related outcomes. Since this practice counters the norm of over-consumption, consumers are wary of the company’s motives. Therefore, consumers make purchase decisions based on their assessment of the “company-cause fit” (Armstrong Soule and Reich, 2015) whereby they ascribe altruistic motives to companies that have a better environmental reputation. If the fit seems to be authentic and based on altruistic motives, consumers have a favorable attitude toward the brand.

A 2010 survey conducted by MIT Sloan Management Review, in partnership with Boston Consulting Group, explored sustainability initiatives implemented by companies around the world. The survey was conducted among approximately 3000 respondents from commercial enterprises in a variety of industries in 113 countries, with more than 40% doing business in at least three regions of the world (i.e. Europe, North America and Australia). Survey results revealed that more respondents than ever before are putting sustainability – environmentally, economically, and socially – into their management agendas (Kiron, et al. 2012). Two thirds of the respondents said that sustainability was critically important to being competitive in the marketplace and about one third said their companies were profiting from sustainable business practices. The question has now shifted from “why should we do sustainability?” to “how do we do it?” While “most companies are struggling to define sustainability in a way that is relevant to their business” those who have succeeded state that sustainability contributes to their profitability (ibid.).

Evident in these examples is the fact that sustainability-related conversations are critical in today’s corporate environment – conversations that cannot be evaded with reactive CSR initiatives. It is imperative for marketing educators to integrate sustainability principles in the curriculum to provide education that reflects real-world issues and better prepares marketing students to face these unique situations. The goal is to move away from the superficial and somewhat short-term needs of stakeholders to focus upon the longer-term, intergenerational social, economic, and ecological impact of a company’s vision, mission, and actions.

In response to growing conversations on the need for the integration of sustainability in business school programs, the Principles of Responsible Management Education (PRME) was established in 2007. This initiative is supported by the United Nations Global Impact and was established by sixty deans, presidents, and representatives from business schools from around the world. PRME describes its purpose as developing “the capabilities of students to be future generators of sustainable value for business and society at large and to work for an inclusive and sustainable global economy” (2017 [4]). In short, the primary purpose of PRME is to aid in the education of students to become future leaders in business and society at large.

One important step in this direction is to foster the type of critical and holistic thinking that is necessary to create marketing practitioners who embrace this broadened understanding of sustainability. To do so, various pedagogical approaches can be developed and implemented in facilitating sustainability-based business education, such as active learning (Hedden et al., 2017; MacVaugh and Norton, 2010) that involves various existing research methods (interviews, action research). In the following sections, we discuss pedagogical examples from various marketing courses that offer innovative ways to foster a sustainability orientation among marketing students who can hopefully evolve into the new, sustainability-oriented marketing practitioners.

Integrating Sustainability into Marketing Curriculum

It is vital that the notion of sustainability be covered beyond the typical application through case studies or readings, or a single course on ethics, as part of a marketing major within the core business curriculum. Instead, it should be integrated throughout the courses and coordinated with both curricular and extracurricular activities. There are various ways to accomplish this objective. In this section, we offer some examples of how sustainability can be integrated more holistically into the marketing curriculum through various core and elective courses (see Table 1).

PDF of Upadhyaya et al Table 1 [5]

Table 1. Integration of Sustainability Principles into Marketing Curricula and Pedagogy

Bascoul et al. (2013) recommend a shift in thinking in marketing education that is required to broaden students’ horizons and train them holistically as future marketers who can look beyond the impact of their decisions on the marketplace and understand how their actions have consequences outside the marketplace. They point to an existing gap between the “significant increase in the importance of environmental protection and sustainability to consumers, policy makers, and society in general” and the “comparatively low level of knowledge that marketing managers actually have of the environmental impact of their own functional decisions” (p. 168). They suggest that this could be due to the narrow marketplace focus of the traditional marketing education programs that educate these future managers. The Life Cycle Assessment method they propose goes beyond the limitations of the traditional Product Life Cycle (introduction, growth, maturity, decline) and takes into account the entire life cycle of a product from raw material extraction to ultimate disposal to gain a better understanding of the environmental impact of marketing decisions and actions (Bascoul et al., 2013).

Similarly, the concept of demarketing becomes a useful one that can be integrated through case-based discussions on ways to reduce environmental costs in the new product development process, branding based on social and environmental causes, tapping into new consumer segments, and reinvesting in environment-friendly technologies. To fully embrace this shift in thinking, we propose the application of a sustainability framework in marketing curricula and pedagogy.

Core Marketing Courses

Principles of Marketing.Almost every contemporary marketing principles textbook contains a chapter dedicated to business ethics to emphasize corporate societal engagements. In fact, going beyond a single chapter on business ethics, Grewal and Levy (2017) include a subsection on ethical and societal dilemmas in every chapter and relate the respective case to the chapter-specific marketing concept. However, as we discussed above, sustainability is much more encompassing than business ethics as it goes beyond the moralistic and ethical dilemmas that managers face. Indeed, sustainability can serve as the very framework for the development of a marketing plan.

The notion of sustainability can be easily integrated into a principles of marketing class through the marketing mix also known as the 4Ps model. Each marketing mix element can be discussed within the sustainability framework. Are products produced sustainably? Are businesses engaging in fair trade practice? Do the prices reflect true costs where laborers are paid fairly? Are local producers/manufacturers preferred over those from which the goods have far to travel? What is the distribution network’s impact on carbon emissions? Are businesses engaging in ethical promotion practices? Are they encouraging consumption to increase their sales or to serve people and societal well-being? These questions impose a broader, critical thinking perspective upon the traditional discussion of the marketing mix.

Consumer Behavior. Nuanced perspectives on various aspects of traditional consumer behaviors and decision making can be unpacked through the integration of a sustainability framework. For example, segmentation is a powerful concept that can provide important insights on the (un)sustainable behaviors of consumers and help identify potential consumption alternatives. The sustainability framework also helps to highlight how different consumer value orientations and consumption motivations influence consumers’ ability and intention to engage in sustainable consumption. For instance, research has shown that consumers are not simply driven by moral and altruistic concerns in engaging in sustainable consumption (Shepherd, 2004). Instead, consumers are very interested in ascertaining the intangible and tangible costs associated with consuming an organic or natural option. Fresh insights on how consumers are thinking of sustainability and what it means to marketing practices helps in the development of critical thinking skills and reasoning – important skills in understanding and adhering to sustainability principles.

Marketing Research. Incorporating sustainability into a marketing research course involves a major shift in the use of tools, metrics, and methods used in assessing business success. The sustainability-focused marketing research course would look beyond the traditional bottom line of business (profits, costs, sales). Instead, it would take into account various measurable indicators in assessing the social, environmental, and economic performance of the business to provide a holistic assessment of the sustainability or profitability of the business. Marketing measurement and analysis may pertain to, but is not limited to, tracking key aspects of performance in natural and human capital, tracking improvements in social and environmental indicators, monitoring the green economy, and analyzing life-cycle assessment (design, manufacture, use, and disposition of a product) (Martin and Schouten, 2012).

Kiron et al. (2012) state that voluntary participation in sustainability measures such as green card score cards, sustainability rankings and CSR metrics, has been driven partly by investors and partly by competitors. Also, advances in technology have enabled more robust capture and synthesis of corporate performance data on these accounts.

Marketing Strategy. Many organizations are now seeking sustainability specialists who can advise and assist in the design, development, implementation, and evaluation of marketing strategies. Marketing strategy courses can effectively address these growing demands for sustainability-oriented marketing professionals by integrating allaspects of sustainability in the marketing strategy planning process – objectives, target markets, goals, tactics, marketing mix – to unpack and re-analyze these traditional marketing concepts (Bridges and Wilhelm, 2008).

Elective Marketing Courses

Sustainability Marketing. Sustainability marketing “is a more holistic, integrative approach that puts equal emphasis on environmental, social equity, and economic/financial concerns in the development of marketing strategies” (Bridges and Wilhelm, 2008, p. 35). This course integrates various aspects of sustainability in the research, design, and development of marketing strategies.The overall goal is to gain an in-depth understanding of various sustainability-related global issues through the use of available online and offline resources (e.g., documentaries). In addition, this elective course includes hands-on projects that require student groups to develop strategies that address opportunities and threats emanating from inconsistent and sometimes contradictory changes in society, the environment, and ecology.

Community-Based Social Marketing. This course re-frames the assumptions that underlie traditional marketing practices and provides a new approach to understanding marketing questions by focusing on various social issues pertaining to health, food insecurity, homelessness, financial illiteracy, animal rights, and water crisis, etc. The goal in this course is not only to make students aware of the social issues embedded in their immediate environment through the use of case studies and videos; but also to educate them on the interconnectedness of environmental, social, and economic issues. The course also highlights the implications of local sustainability-related issues that are global in nature (e.g., poverty, food insecurity, etc.). Further, this course adopts the 10-step social marketing plan developed by Kotler and Lee (2015) in the research, design, development, implementation, and assessment of a social marketing plan to develop a strategy to better address an aspect(s) of a social issue.

Sustainable Retailing. Retailers, as the link between the suppliers and the consumers, could act as “ecological gatekeepers” (Belz, 1996) by changing manufacturers’ production processes and influencing consumer’s consumption patterns through providing information on social and environmental issues related to the supply chain (Erol et al., 2009; Yang et al., 2017). Retailers can also adopt sustainable practices through their delivery, packaging, and assortment (Yang et al., 2017). Sustainable retailers are referred to as those who “minimize emissions, effluents, and waste through continuous improvement in their internal operations” (Tang et al., 2016). This course analyzes the environmental impacts of various retail management operations and the associated benefits and opportunities, as well as best practices and processes in sustainable retail operations. Course learning objectives include evaluating sustainable strategies for working with key stakeholders; evaluating industry claims with respect to environmental dimensions such as certified, organic, fair trade products and practices; applying the techniques of cost/benefit analyses to sustainable retail operations; assessing how retail technology innovations can maximize sustainable strategies; and creating strategies for setting, implementing, and assessing retailing goals for sustainability (RMT 345, 2017). The focus of the course can be the fashion or food industries where most waste occurs.

Sustainable Product Design and Innovation. Due to the multi-faceted nature of the topic, this course can be taught as an interdisciplinary one in collaboration with engineering and/or science departments focusing on the design and promotion of a new product with the lowest environmental footprint. Currently similar courses are taught across various disciplines ranging from design (e.g. Parsons School of Design) to public health schools (e.g. Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health).

According to Keene State College in New Hampshire, which offers a four-year program with a cross disciplinary curriculum, sustainable product design “involves the synthesis of consumer needs and production capabilities in the creation of new products and their affiliated services. The integrated sustainability issues link the multitude of human factors, environmental, and resource depletion concerns to the decision-making process.” (n.d.)

Mandatory and voluntary requirements for sustainable product design can contribute to a firm’s bottom line in terms of cost-cutting, profitability, competitive advantage, product positioning, and branding. In a typical class, student teams design and develop innovative and environmentally friendly products based on sustainability principles and market their innovations wary of “green washing.”

Integrating Sustainability into Pedagogy

The facilitation of sustainability-framed marketing courses may involve different approaches, ranging from in-class exercises to hands-on working experiences with a non-profit or business entity. In-class activities help equip students with concepts and tools required to carry out informed research. Similarly, experiential learning involves “learning activities that engage the learner directly in the phenomena being studied” (Cantor, 1995, p. 1). These activities can range from visiting a community or a facility to working in an internship (Brundiers et al., 2010; Domask, 2007). Experiential learning helps students get a better understanding of the course topics by connecting students with practitioners and stakeholders and connecting the academic component with practice. In this section, we briefly describe various pedagogical approaches used in five different courses.

Principles of Marketing. In order to provide introductory knowledge on sustainability-related issues, principles of marketing courses can employ several high-quality, award-winning documentaries that are easily accessible via online streaming services or university libraries. While it is not our intention to provide an exhaustive list of documentary films in this paper, we provide a few examples to illustrate how documentaries can be used in marketing courses in an effort to create awareness about the critical role of marketing. For instance, the documentary The True Cost(2015) focuses on supply chain management (from manufacturing to retail) in the fashion industry–the second biggest polluter after the oil industry. The True Costfollows the story of textiles and garments from the production stage at the farm and factory level to the consumption stage at the consumer level, and shines a bright light on the behind-the-scenes activities of the fashion industry and its damaging effects on people and the environment. Another documentary, Dive(2009), is one of many that looks into food waste in the United States and the world as well as how marketing practices contribute to the increase in food waste. Fashion and food are two topics that are closely relevant to college students’ everyday lives. Therefore, the issues discussed in these films are easily identifiable by and relatable to the students.

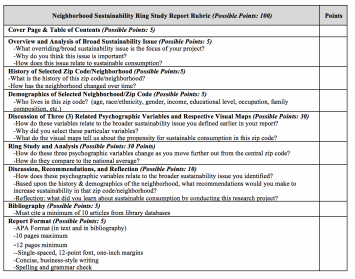

Consumer Behavior. The sustainability-integrated curriculum for this course incorporates different pedagogical tools in maximizing learning outcomes. Field trips can be organized to provide students a real-world understanding of some of the most pressing sustainability issues. For instance, trips to local farmers markets can provide students with multi-sensory experiences of sustainable consumption that connect perfectly into a discussion of the consumer motivation, especially LOHAS (Lifestyles of Health and Sustainability), and conscientious consumption, as well as psychographics and market segmentation. Further, course projects based on active learning stages are instrumental in fostering important critical thinking skills. In one example, a neighborhood ring study (see Table 2), students combine visual observations of a selected neighborhood with demographic and psychographic research to measure the propensity for sustainable consumption.

PDF of Upadhyaya et al Table 2 [7]

Table 2. Pedagogy Example: Consumer Behavior Course Sustainable Consumption Project – Neighborhood Ring Study

PDF of Upadhyaya et al Table 3 [9]

Table 3. Grading Rubric for Consumer Behavior Course Sustainable Consumption Project Report – Neighborhood Ring Study

Sustainability Marketing. Experiential learning in this course involves a field trip to a local recycling center and teaches the students about product and packaging design and policies as well as how they differ in various countries around the world. Standing next to a pile of trash that has been sent to a local recycling center is an eye-opening experience for most students. The abstract notion of waste becomes a concrete experience with which they can visually and physically relate. The problem is now real — it is no longer just a disturbing visual in a textbook or documentary but rather a tangible reality that they can experience with their senses. Alternatively, a trip to a landfill or hydrogen fuel cell plant can provide students with a first-hand understanding of the importance of excessive consumption or energy conservation and the efforts made in that direction.

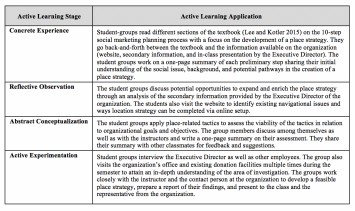

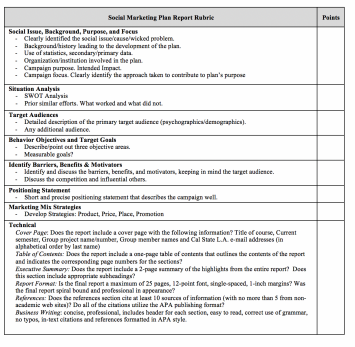

Community-Based Social Marketing. Sustainability principles are inherent in this course as well. While focusing primarily on the social aspect of sustainability, this course also delves into the economic and ecological aspects. Various pedagogical methods are useful in knowledge dissemination. For instance, documentaries, case-studies, and online videos can be used in the facilitation of this course. Students visit a local site to gain a first-hand perspective in the process of conducting a case analysis. The case study involves direct observation in a local neighborhood and provides students with the opportunity to observe, document, and reflect upon the impact of gentrification. Further, student engagement can be fostered through experiential learning projects involving collaboration with an actual non-profit organization in developing strategies to address a specific social issue. Students enrolled in this course work with nonprofit organizations that are focused on different social issues such as food insecurity, medical equipment loans, youth joining gangs, mixed-income housing, and after-school programs for low-income families. Adopting the active learning stages illustrated in Tables 2 and 4, students engage in the development of an in-depth, research-driven, implementable solution to a research question that pertains to a social issue developed in conjunction with the collaborating organization (see Table 3). The students also integrate the 10-step social marketing plan developed by Kotler and Lee (2015) in organizing their research process, the final report, and presentation.

In a specific example of working directly with a local non-profit organization, (see Table 4), students meet with a local non-profit organization to identify ways to increase durable medical equipment donations. Such donations are important to communities because they ensure the availability of free or low-cost equipment loans and purchases to benefit the residents of a community. In the case of the community partner with whom we worked, the donation of durable medical equipment is also a highly sustainable model for the community because the equipment is donated (rather than going into landfills), repaired by volunteers, professionally sanitized on site, and loaned out to community members at no cost.

PDF of Upadhyaya et al Table 4 [11]

Table 4. Pedagogy Example: Community-Based Social Marketing Course

PDF of Upadhyaya et al Table 5 [13]

Table 5. Grading Rubric for the Community-Based Social Marketing Assignment

Sustainable Retailing. The topic of thiscourse lends itself to experiential learning as well–students engage hands-on with theoretical concepts and apply them to the out-of-classroom context. One suggested assignment is a client-based project to study local retail businesses and assess their sustainability efforts. Students work in groups as consultants in assessing the retail businesses’ store operations, waste reduction and recycling processes, and claims with respect to the triple bottom line (people, planet, profit). Based on their assessments, students prepare a sustainability report that is actionable for the specific retail store. Best practices and processes in different retail stores can be compared for further analysis.

Limitations

In this paper, we presented concepts and ideas for developing marketing curricula and pedagogy that are integrated with a broader understanding of sustainability. As curriculum design is a rather complex undertaking and goes beyond the design of core and elective courses within a department or discipline, these concepts and ideas have limitations. An ideal curriculum would be an interdisciplinary one that integrates learning across pedagogy and theory.

The field trips we discuss and recommend in this paper require financial support from the administration, as well as additional coordination and facilitation from the instructors. For institutions and departments who lack the financial and/or human capital to accomplish such objectives, such efforts can be daunting. In addition, the redesign of curriculum to reflect a new paradigm of sustainability would require political buy-in from several different constituencies from the top to the bottom of an organization.

Conclusion

Despite the challenges and limitations, it is important for marketing education and educators to align with growing calls to address the complex issues that pertain to society. Developing sustainability-based marketing curricula and pedagogy is a sound place to start the conversation. And, the practice of nurturing future generations’ sensitivity toward the long-term impact of marketing is well worth the effort. The goal of curriculum re-invention also compels marketing educators, business school administrators, and other stakeholders to become more aware and cognizant of the irreversible and direct impact (positive and negative) that marketing decisions have upon consumers and the broader material and social environment in which they live.

References

AACSB International. (2017). AACSB Criteria and Standards for Business Education. Retrieved on from:http://www.aacsb.edu//media/aacsb/docs/accreditation/standards/business-accreditation-2017-update.ashx?la=en

Armstrong Soule, C. A., and Brandon J. R. (2015). Less is more: is a green demarketing strategy sustainable?, Journal of Marketing Management, 31(13-14), 1403-1427.

Astor, M. (2017, October 8). Dove Drops an Ad Accused of Racism, New York Times, Retrieved from: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/10/08/business/dove-ad-racist.html [15].

Bascoul, G., Schmitt, J., Rasolofoarison, D., Chamberlain, L., & Lee, N. (2013). Using an experiential business game to stimulate sustainable thinking in marketing education,Journal of Marketing Education, 35(2), 168-180. https://doi.org/10.1177/0273475313491497 [16]

Belz, F. (1996). Food retailers as ecological gatekeepers. An international comparison between Switzerland and Sweden in Proceedings of the Fifth International Research Conference of the Greening of Industry Network, Heidelberg, Germany, November 1996, 24-27.

Borin, N., & Metcalf, L. (2010). Integrating sustainability into the marketing curriculum: learning activities that facilitate sustainable marketing practices, Journal of Marketing Education, 32(2), 140-154.

Bridges, C., & Williams, W. B. (2008). Going beyond green: The “why and how” of integrating sustainability into the marketing curriculum, Journal of Marketing Education, 30(1), 33- 46.

Brundiers, K., Wiek, A., & Redman, C. L. (2010). Real-World learning opportunities in sustainability: from classroom into the real world, International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 11(4), 308-324.

Burns, H. (2011). Teaching for transformation: (re) designing sustainability courses based on ecological principles,Journal of Sustainability Education, 2, 1-15.

Cantor, J. A. (1995). Experiential Learning in Higher Education: Linking Classroom and Community, ASHE-ERIC Higher Education Report, No. 7.

Domask, J. J. (2007). Achieving goals in higher education: An experiential approach to sustainability studies, International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 8(1), 53-68. Doi:10.1108/14676370710717599 [17]

Erol, I., Cakar, N., Erel, D., & Sari, R. (2009). Sustainability in the Turkish retailing industry,Sustainable Development, 17, 49–67.

Eweje, G. (Ed.) (2014), Corporate Social Responsibility and Sustainability: Emerging Trends in Developing Economies, Emerald Group Publishing: Somerville, MA.

Germano, M., Houston, H. R., & Stretch-Stephenson, S. (2015). Teaching sustainable consumption: experiential exercises and projects for consumer behavior and marketing courses in Teaching Marketing to New Generations and Non-Traditional Students.Proceedings of Marketing Educators’ Association Conference, Las Vegas, NV, 148-149.

Grewal, D., & Levy, M. (2016). Marketing.McGraw Hill Education: New York, NY.

International Institute for Sustainable Development. www.iisd.org [3].

Kalamas, H.M., Worthy, R., Akins, E., Slinger-Friedman, V., & Paul, R. (2017). Teaching sustainability using an active learning constructivist approach: discipline-specific case studies in higher education, Sustainability, 9(8):1320,1-18.

Jabbour, C. J. C. (2010). Greening of business schools: a systemic view, International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 11(1), 49-60.

Kiron, D., Kruschwitz, N., Haanaes, K., & von Streng Velken, I. (2012). Sustainability nears a tipping point, MIT Sloan Management Review, Winter. Retrieved from: https://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/sustainability-nears-a-tipping-point/ [18]

Keene State College. (n.d.) Sustainable Product Design and Innovation. Retrieved from https://www.keene.edu/catalog/programs/detail/sustainable-product-design-and-innovation-bs/ [19]

Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential Learning.Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ.

Kotler, P., & Lee, N. (2015). Social Marketing: Changing Behaviors for Good. Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA.

Kotler, P., & Levy, S. J. (1971). Demarketing, yes, demarketing. Harvard Business Review, 79, 74-80.

Lakshmi, R. (2016, March 9). After Fifteen Years, Unilever Settles With Indian Factory Workers Over Mercury Poisoning, Washington Post, Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/worldviews/wp/2016/03/09/after…ian-factory-workers-over-mercury-poisoning/?utm_term=.f652731660f9 [20]

Lim, W. M. (2016). A blueprint for sustainability marketing: defining its conceptual boundaries for progress, Marketing Theory, 16(2), 232–249.

MacVaugh, J., & Norton, M. (2012). Introducing sustainability into business education contexts using active learning, International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 13(1), 72- 87.

Martin, D., & Schouten, J. (2012). Sustainable Marketing. Prentice Hall: New York, NY.

Mather, G., Leanne D., Leigh W., & Bronwen H. (2010). Business graduate skills in sustainability,Journal of Global Responsibility, 2(2), 188-205.

PRME. (2017). Retrieved from http://www.unprme.org/reports/SIPreportfinal.pdf [4]

Roff, P. (2017, March 23). Corporate Imaging: Unilever CEO Paul Polman’s Sustainability Effort Covers Up the Fact That His Business Practices Are Unsustainable, U.S. News, Retrieved from: https://www.usnews.com/opinion/thomas-jefferson-street/articles/2017…ver-ceo-paul-polman-reveals-corporate-sustainability-can-be-all-show [21]

RMT 345. (2017). Sustainable Retailing Course Syllabus. Department of Information Technology and Administrative Management, Central Washington University. Retrieved from http://www.cwu.edu/it-management/sites/cts.cwu.edu.it-management/files/documents/RMT345_Gen_2017.pdf [22]

Siemens. (n.d.) Practicing Sustainability in the Interest of Future Generations. Retrieved from https://www.siemens.com/global/en/home/company/sustainability.html [23]

Shepherd, R. (2004). Determinants of consumer behaviour related to organic food in The Food 21 Symposium: Towards Sustainable Production and Consumption, 88-90.

Stewart, M. (2010). Transforming higher education: a practical plan for integrating sustainability education into the student experience, Journal of Sustainability Education, 1(1), 195-203.

Stubbs, W., & Chris, C. (2008). Teaching sustainability to business students: shifting mindsets,International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 9(3), 206-221.

Stubbs, W., & Schapper J. (2011). Two approaches to curriculum development for educating for sustainability and CSR, International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 12(3), 259-268.

Tang, A. K. Y., Lai, K. H., & Cheng, T. C. E. (2016). A multi-research-method approach to studying environmental sustainability in retail operations, International Journal of Production Economics, 171, 394–404.

Too, L., & Bajracharya, B. (2015). Sustainable campus: engaging the community in sustainability, International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 16(1), 57-71.

Üçok Hughes, M. (2015). Design and implementation recommendations for an undergraduate sustainable marketing course, in Teaching Marketing to New Generations and Non-Traditional Students.Proceedings of Marketing Educators’ Association Conference, Las Vegas, NV, 163-169.

Unilever. (n.d.). Sustainable Living. Retrieved from https://www.unilever.com/sustainable-living/ [24]

United Nations. (1987). Our Common Future: Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development (The Brundtland Report). General Assembly Resolution 42/187, 11 December. Retrieved from:https://www.are.admin.ch/are/en/home/sustainable-development/international-cooperation/2030agenda/un-_-milestones-in-sustainable-development/1987–brundtland-report.html [25]

Weybrecht, G. (2015, June). State of Sustainability in Management Education, Shaping the Future Business Leader: State of Sustainability Education Overview, PRME (Principles for Responsible Management), Retrieved from:http://www.unprme.org/resource-docs/SFBLStateofSustainabilityEducationOverview.pdf [26]

Wilhelm, W. B. (2008). Marketing education for sustainability, Journal for the Advancement of Marketing Education, 3, 8-20.

Wymer, W., & Rundle-Thiele, S. R. (2017). Inclusion of ethics, social responsibility, and sustainability in business school curricula: a benchmark study, International Review on Public and Nonprofit Marketing, 14, 19-34. Doi: 10.1007/s12208-016-0153-z

Yang, S., Song, Y., & Tong, S. (2017). Sustainable retailing in the fashion industry: a systematic literature review, Sustainability, 9, 1266. Doi:10.3390/su9071266