Full PDF: Gardner JSE Vol 7 Dec 2014 [1]

Abstract: Finding out what students enjoy most, and designing a teaching curriculum to include those enjoyable activities, is the key to motivation and learning in a nontraditional educational environment. At the Maryland Correctional Institution in Jessup, ESL students love art expression in any form, thus, the instructor is determined to use it as a teaching tool in the classroom. Art expression integrated into the state content standards for adult ESL has allowed minority language students to shine as artists in their own right. It also allows the instructor to connect with students who have dropped out, never attended, or had negative experiences with traditional pedagogy. This connection and artistic expression has provided the needed incentive for critical literacy and academic success.

Key Words: ESL, correctional education, critical literacy, multiple literacies, artistic expression, tattoo art, adult education

![]() [2]Adult educators in the United States with nontraditional populations face the monumental task of how to motivate students who have not completed their K – 12 educations. These students include those with negative educational experiences or gaps in their learning histories, adults with limited formal education, special education students, and students who have been discriminated against and marginalized due to language, race, addictions, and behavior. An education for sustainable development allows such students to become engaged in the learning process through meaningful dialogue and learner-centered instruction. In turn, this creates an environment where students feel safe to discuss their hopes and fears for the future and how education can play an important part. At the Maryland Correctional Institution in Jessup (MCI-J), English-as-a-second-langue (ESL) students use personal artistic expression to enhance English dialogue and meaningful conversation as they develop critical thinking skills, skills which will enable them to make positive and sustainable decisions for their futures.

[2]Adult educators in the United States with nontraditional populations face the monumental task of how to motivate students who have not completed their K – 12 educations. These students include those with negative educational experiences or gaps in their learning histories, adults with limited formal education, special education students, and students who have been discriminated against and marginalized due to language, race, addictions, and behavior. An education for sustainable development allows such students to become engaged in the learning process through meaningful dialogue and learner-centered instruction. In turn, this creates an environment where students feel safe to discuss their hopes and fears for the future and how education can play an important part. At the Maryland Correctional Institution in Jessup (MCI-J), English-as-a-second-langue (ESL) students use personal artistic expression to enhance English dialogue and meaningful conversation as they develop critical thinking skills, skills which will enable them to make positive and sustainable decisions for their futures.

If you were to visit the English as a Second Language (ESL) classroom at the Maryland Correctional Institution in Jessup, Maryland (MCI-J), you would find all kinds of student-made artistic expression on display. There are student profiles in black construction paper mounted on the vast white walls of the classroom; there are elaborate red and pink valentines expressing various sentiments (I Love You, Mom) posted by the door; there are original alphabet cards in a rainbow of colors, representing personal interpretations of individual letters. A hand-made Siguanaba doll with long black yarn for hair and beautiful hand-sewn clothes stands atop the filing cabinet for all to admire. She elicits wonder and amusement from all who see her. If you look closer around the room, you will see more personal art expression in the form of body art—tattoos–on the students themselves. These artistic tattoos represent students’ identities, life styles, and images they love–a beautiful lifelike portrayal of a baby; a rose vine slithering up a large crucifix; a true-to-size Cannabis plant complete with leaves and flowers; and gang numbers marked clearly on one’s neck. Art activity is commonplace in the ESL classroom at MCI-J; it is personal, expressive, and emotional—all good characteristics for a language class. In a correctional education setting, this art activity can serve as a link to a world of learning and critical literacy, and it provides motivation to students who have previously dropped out of school and ultimately found themselves behind prison walls.

Background

MCI-J is a men’s state prison located in the suburbs of Baltimore. It houses about 1,024 inmates at three different security levels: minimum (a sentence of less than five years), medium (five to ten years), and maximum (more than ten years).

Inmates who do not have a high school diploma or equivalency are mandated to attend the MCI-J school (located on premises) for 120 days when they enter the correctional system. It is hoped that men will stay in school longer, if needed, in order to attain a high school diploma or appropriate level literacy certificate. These literacy certificates reflect the various academic classes in the school– ESL, Special Education, Basic Literacy, Intermediate Levels 1, 2, 3, and 4, and Adult Secondary Education Levels 1, 2, 3, and 4.

The ESL Program

The ESL program at MCI-J enrolls twenty-four (24) Latino men, ages 19-56, divided between two classes. These students represent six different countries—Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, Puerto Rico, and Peru. The students enter the program with varying language abilities—many have functional conversational skills but low academic literacy in both English and Spanish, their first language.

As the ESL instructor, I am charged with teaching these men an integrated curriculum in English as a Second Language including listening, speaking, reading, and writing. Students learn conversational English in addition to literacy.

What is art? What is language?

For this article, art is defined as that tangible creation, something produced through painting, drawing, sewing, singing, writing, acting, building, or constructing—a production of “personal, unanalyzable creative power” (Merriam-Webster, 1994, p. 654). Art production involves skill, imagination, or replication and is decorative or illustrative. The term “language” is used when speaking about forms of communication. It can be informal such as speaking and uttering, or it can be formal, such as writing. Language may include sounds, gestures, marks, words, letters, signs, and symbols. For teaching purposes, there are four areas of language—listening, speaking, reading, and writing. An integrated ESL curriculum involves listening, not just to the teacher, but to others in the classroom; speaking about every subject being learned; reading about the same content; and writing at one’s ability. Thus, students speak about what they see; they write about what they learn; and they read about what they write.

Art production and language instruction in a multicultural curriculum promote critical literacy.

[3]Art production used to enhance language instruction results in a very personal experience for not just the artist and creator, but for the class, too, with ethnicity and culture being an integral part of both the art creation and ensuing discussions in English. When students from other countries are allowed and encouraged to bring forth indigenous ideas and customs to classroom assignments, the result is a classroom that learns to respect the opinions of, and be sensitive to, others. This is part of, and is generally referred to as diversity or multicultural education. Multicultural ideas and concepts are much more than just holidays and food, but instead bring totality of a true learning experience which involves thinking and learning from all perspectives—social, political, economic, geographic, cultural, etc. In a multicultural pedagogy, all student experiences are valued and validated by discussion and discourse. Because multiculturalism in an ESL classroom is by definition personal, it can be the basis for all instruction in the class. New learning is enhanced by the inclusion of other languages, learning styles, individual perspectives, and other cultural aspects incorporated into the lesson. Urrieta and Quach (2000) stress the importance of multicultural instructional methods when teaching minority language students in order to promote critical literacy, an approach that promotes inquiry, discourse, and meaning about the world and one’s identity in it. Critical literacy is thought to be the key to empowerment of minority students as it helps them identify their place in society through thoughtful discussion and reflection. It is often considered in conjunction with the concept of multiple literacies (Gallego, M.A. & Hollingsworth, S., 2000), which include school literacy (for academic purposes), community literacy (understanding, appreciating, and using cultural norms), and personal literacy (self-awareness and self-identity), all of which provide alternative ways of thinking, interpreting, and acting based on life experiences and culture. Although traditional schooling in the U.S. involves making sense out of print and text (reading), and producing one’s own print and text (writing), there are today many educators who sanction the use of alternative methods of literacy development (Gee, 1989; Gallego & Hollingsworth, 2000; Kirkland, 2009; Vocke, 2004). These nontraditional methods focus on 1) having authentic conversations that are meaningful to students; 2) discussing class material with people of their choice; and 3) having time in class to do it (Vocke, 2004). Vocke emphasizes that it is the free choice and response incorporated into the assignment that engages students in the learning process and develops literacy. Engaging in art production is one such form of nontraditional pedagogy that works well for all forms of literacy instruction at MCI-J—students love to draw, doodle, paint, tattoo, and sew.

[3]Art production used to enhance language instruction results in a very personal experience for not just the artist and creator, but for the class, too, with ethnicity and culture being an integral part of both the art creation and ensuing discussions in English. When students from other countries are allowed and encouraged to bring forth indigenous ideas and customs to classroom assignments, the result is a classroom that learns to respect the opinions of, and be sensitive to, others. This is part of, and is generally referred to as diversity or multicultural education. Multicultural ideas and concepts are much more than just holidays and food, but instead bring totality of a true learning experience which involves thinking and learning from all perspectives—social, political, economic, geographic, cultural, etc. In a multicultural pedagogy, all student experiences are valued and validated by discussion and discourse. Because multiculturalism in an ESL classroom is by definition personal, it can be the basis for all instruction in the class. New learning is enhanced by the inclusion of other languages, learning styles, individual perspectives, and other cultural aspects incorporated into the lesson. Urrieta and Quach (2000) stress the importance of multicultural instructional methods when teaching minority language students in order to promote critical literacy, an approach that promotes inquiry, discourse, and meaning about the world and one’s identity in it. Critical literacy is thought to be the key to empowerment of minority students as it helps them identify their place in society through thoughtful discussion and reflection. It is often considered in conjunction with the concept of multiple literacies (Gallego, M.A. & Hollingsworth, S., 2000), which include school literacy (for academic purposes), community literacy (understanding, appreciating, and using cultural norms), and personal literacy (self-awareness and self-identity), all of which provide alternative ways of thinking, interpreting, and acting based on life experiences and culture. Although traditional schooling in the U.S. involves making sense out of print and text (reading), and producing one’s own print and text (writing), there are today many educators who sanction the use of alternative methods of literacy development (Gee, 1989; Gallego & Hollingsworth, 2000; Kirkland, 2009; Vocke, 2004). These nontraditional methods focus on 1) having authentic conversations that are meaningful to students; 2) discussing class material with people of their choice; and 3) having time in class to do it (Vocke, 2004). Vocke emphasizes that it is the free choice and response incorporated into the assignment that engages students in the learning process and develops literacy. Engaging in art production is one such form of nontraditional pedagogy that works well for all forms of literacy instruction at MCI-J—students love to draw, doodle, paint, tattoo, and sew.

Art and language are personal and reflect our culture and ethnicity.

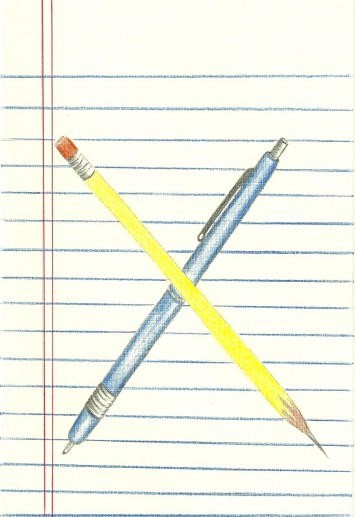

Incarcerated students in the ESL class are by definition “minority language students.” In the class are many adults who have limited exposure to an academic setting with only two or three years of formal schooling in their first language and limited formal instruction in their second language. In order for them to discover that they bring forth valuable ideas and experiences to a traditional school setting, they must be given the tools and means to see themselves as people who know about many things ( Freire, 2010) —things that are unique and personal that only they can relate and share with others in the class. As their ESL instructor, I have discovered that art engagement is what my students love the most, and it is the most successful pedagogy to their sharing and learning in a new language. Above all other possessions, a set of colored pencils or pens is coveted and valued for what it represents—freedom to illustrate and portray images and symbols that represent their own ideas and visions. This is true whether they are illustrating English vocabulary, thinking of loved ones, or making a statement about their personal beliefs. Art participation gives a voice to all, which is especially crucial for students who are unable to express themselves socially, emotionally, or linguistically.

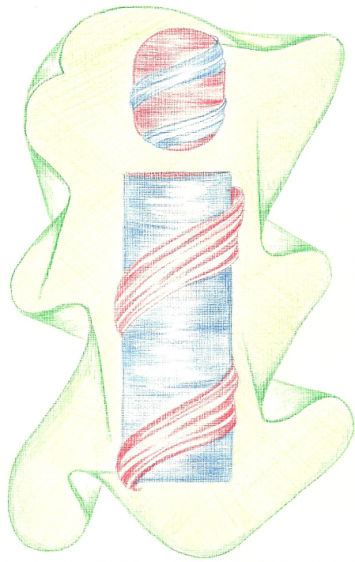

Because culture is a huge part of any literacy development, adult educators should always include multicultural education in the curriculum. Any lesson can easily be augmented with a cultural component, and art production is a good conduit for such a lesson. For example, in ESL, a beginning unit includes English phrases and small talk used in introductions. An instructor can easily incorporate other languages into the lesson—Hello in English, Hola in Spanish, Bonjour in French, etc., all easily found on the Internet. A study of one word in English becomes a new language experience—practicing other ways to say Hello; a geography lesson—locating the countries on the map; a lesson in diversity—acknowledging that people in the U.S. speak other languages besides English; and accessing prior knowledge–discussing what we know about the people and culture of each country mentioned. It can also become an art activity. Because many of the ESL students at MCI-J have experience in graffiti and street art, illustrating words is an art activity that appeals to them. Because they love to draw, a simple word Hello can become a word of script, block letters, or calligraphy, with elaborate designs tacked on to each letter, each symbol culled from students’ vast experiences and memories from other places. The word art Hello on page 1 of this article was the first English word that Jorge was able to read when he crossed the border from Mexico into Arizona. His memory includes the hot dry desert (illustrated therein) and hope for the future. Thus, an English word set the stage not just for language learning, but for a discussion on geography, culture, and life in the United States. Multiculturalism in the curriculum helps to reduce prejudice by teaching students about other lifestyles, beliefs, and  [4]traditions, the understanding being that the more they know about someone or something, the less fearful, and more accepting, they will be. Art is a valuable channel to that lesson in diversity in a correctional setting where violence is commonplace between races, ethnicities, and gangs.

[4]traditions, the understanding being that the more they know about someone or something, the less fearful, and more accepting, they will be. Art is a valuable channel to that lesson in diversity in a correctional setting where violence is commonplace between races, ethnicities, and gangs.

Art activities promote real conversations.

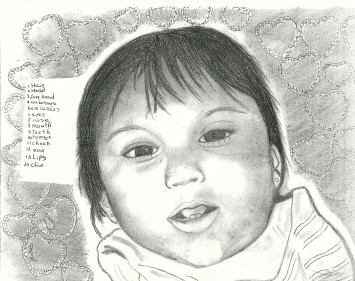

Creating art is a very personal activity, and the process of presenting it to others during a language lesson leads to real conversations, not just repetition of words and phrases. For example, a unit on family can easily be personalized by having students draw a portrait of a family member. Such is the case with the illustration herein of baby Angela. Angela’s father spent two evenings drawing her lovely image from a wallet-size photo. When finished, the student brought it to class and presented the portrait, “This is my daughter. Her name is Angela. She is one year old and lives with her mother. They live in Prince George’s County.” Thus, he fulfilled the teacher’s prompt to “tell the  [5]class something about your family.” The artwork became the foundation for conversation that was not just familiar, fun, and personal, but also cognitively challenging in many ways– social, political, economic, geographic, and cultural, as Angela’s father discussed the problems of being away from his daughter.

[5]class something about your family.” The artwork became the foundation for conversation that was not just familiar, fun, and personal, but also cognitively challenging in many ways– social, political, economic, geographic, and cultural, as Angela’s father discussed the problems of being away from his daughter.

Ovando, Combs, and Collier (2006) note that art expression stimulates development in many areas, including linguistic, cultural, cognitive, and affective (p. 107). These four areas of learning are important for internalizing language—not just understanding new words but using them in everyday conversation. When students use art as part of their school experience, they become engaged in the totality of the new learning in all four of these areas mentioned above—they consider the language itself (“county” versus “country”); they think about new concepts from a cultural perspective (students make and send valentines, cards, and letters to their mothers and sisters, but not to brothers and fathers); they think about the main subject or idea (yes, the Siguanaba story is a folk tale); and they use emotion in both art and language production (a sad tale of vehicular homicide ends up as a tattoo of two nieces killed).

To the class, Angela’s story was not just a narrative in a book, but an account in real life, represented by a real picture, with the background information as intriguing and suspenseful as any spy thriller. The new learning that occurred is what Wesley (2007) describes as the special place that artists take us, a place where we find beauty and many ways of learning and knowing (p. 13). At every level, from isolated vocabulary words (forehead, face, eyebrows, eyelashes) to worldviews about bilingual education and U.S. immigration policy, students expressed an opinion with the vocabulary at their level. And by presenting his child to a class of individuals from different countries, gangs, and backgrounds, the student revealed something sacred and special about his life. Not only did he tell us about Angela, he showed us her picture, visually and emotionally connecting us to his family, who he loves dearly. Students learned not just new vocabulary and phrases, but discussed family separation, immigration, and deportation (her father is not a U.S. citizen and will be deported upon completion of his sentence.) Students had new realizations that they were not isolated and alone, but classmates together learning to express themselves with clarity and fluency. In our discussions, we had modeled caring and empathy so that others could learn to care and empathize, too. I must note here that my students eagerly participate in all kinds of discussions that are family-related; they are separated for long periods of time from families, friends, and jobs and tend to lose connections with people. The classroom discourse among teacher and fellow students becomes a surrogate for conversation with family and friends, which in turn provides the needed emotional investment for conversing in a second language in an ESL classroom. I see this process as emotional literacy, what Pleasants (2007) describes as learning about one’s own emotions through identification with others with similar traits. As one understands more about himself, he is able to transfer this understanding to others, developing compassion, empathy, and love, which are important goals for us all.

Art and language are expressive in many forms.

[6]Language and art are both expressive, and used together they provide passion for creativity and discourse. A visual image as a prompt for writing or speaking can result in many ideas within the classroom. The President’s Committee on the Arts and Humanities (PCAH, 2011) has advocated re-investing resources in arts education in order to promote “creative, collaborative, innovative thinkers” (p. 29). PCAH embarked on interviews of educational and business leaders, conducted extensive reviews of research and opportunities, and made recommendations that arts education will assist students in acquiring the skills needed in today’s competitive global economy. PCAH advocates arts education, not as a separate subject, but incorporated into core content curriculums in order to enhance traditional pedagogy. Correctional educators, who are teaching inmate students who will return to society, must take note of PCAH’s recommendation and incorporate the arts in their school instruction in order to foster critical thinking and problem-solving.

[6]Language and art are both expressive, and used together they provide passion for creativity and discourse. A visual image as a prompt for writing or speaking can result in many ideas within the classroom. The President’s Committee on the Arts and Humanities (PCAH, 2011) has advocated re-investing resources in arts education in order to promote “creative, collaborative, innovative thinkers” (p. 29). PCAH embarked on interviews of educational and business leaders, conducted extensive reviews of research and opportunities, and made recommendations that arts education will assist students in acquiring the skills needed in today’s competitive global economy. PCAH advocates arts education, not as a separate subject, but incorporated into core content curriculums in order to enhance traditional pedagogy. Correctional educators, who are teaching inmate students who will return to society, must take note of PCAH’s recommendation and incorporate the arts in their school instruction in order to foster critical thinking and problem-solving.

The stories are important.

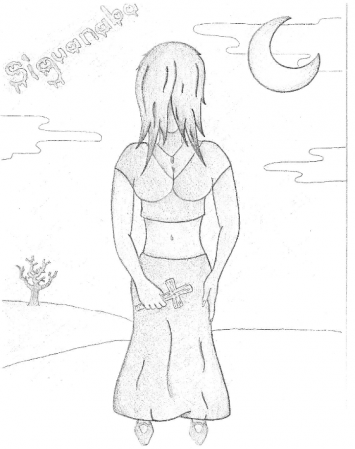

Art and language are two mediums through which stories are told, the first through a visual or  [7]perceptive image, the second through communication. Such is the case with the Siguanaba doll made during a unit on folk tales in literature. The story of the Siguanaba is a Latin American tale originally told by the local priests to the men of the villages in order to inhibit excessive use of alcohol. La Siguanaba seemed to be a beautiful woman with long black hair who would beckon drunken men as they came out of the bars. She would lure them into a wooded area, but as she lifted the long hair out of her face, one could see that she was really a witch. She would then, of course, attack the men with her sharp-as-knives fingernails and devour them. This tale elicited many emotional responses from my ESL class of Latino men. Many students had actually seen La Siguanaba themselves, or knew someone who had. The personal stories were endless and because they were familiar, they channeled an understanding of folk tales and their place in literature, and how they evolve.

[7]perceptive image, the second through communication. Such is the case with the Siguanaba doll made during a unit on folk tales in literature. The story of the Siguanaba is a Latin American tale originally told by the local priests to the men of the villages in order to inhibit excessive use of alcohol. La Siguanaba seemed to be a beautiful woman with long black hair who would beckon drunken men as they came out of the bars. She would lure them into a wooded area, but as she lifted the long hair out of her face, one could see that she was really a witch. She would then, of course, attack the men with her sharp-as-knives fingernails and devour them. This tale elicited many emotional responses from my ESL class of Latino men. Many students had actually seen La Siguanaba themselves, or knew someone who had. The personal stories were endless and because they were familiar, they channeled an understanding of folk tales and their place in literature, and how they evolve.

The artist who volunteered to make the Siguanaba doll constructed her true to his family’s version of the tale. Her long black hair hung in front of her face, and her clothes were attractively positioned on her stuffed sock body. She had sandals on her feet made from brown plastic food wrappers, and she held a beautiful white crucifix made of yarn in her hand. Not only did the class learn the names of the specific materials used to make her, they also learned more complex language structures to express opinions, summarize stories, compare and contrast different versions of the same story, and arrive at conclusions concerning the fate of those who had seen her. The physical characteristics of the doll challenged the men to say and express what was on their minds.

By expressing themselves enthusiastically (in this lesson, using the past tense), they took their unique culture and history and made it their own story, full of energy and passion. In correctional education classes, it is this energy and passion that motivate students to multiple forms of literacy. Because inmates are regulated in almost everything they do, and lives are structured around the same daily routine, students have a tendency to become complacent and passive. Just as they wait for orders from correctional officers, they wait for instructions from teachers. In their ordinary lives, they are not allowed to venture outside the accepted protocol. In class, their minds shut down and they wait. Educators must find what kinds of activities bring students out of their shells, and into an active state of learning. Educators must discover what their students love to do. In my class, my adult students like to be engaged in anything visual or tactile—anything they can see, touch, or play provides motivation. (See Author, 2011.) Art engagement fits this requirement perfectly–although the Siguanaba doll was made years ago, it continues to provoke an expressive response from all who see her.

Art and language are emotional and invoke students to a response.

[8]For beginning ESL students, it is hard to put emotion into learning a second language. English is difficult to learn, especially if there is limited school literacy in the home language. Parts of speech and other grammar rules can be mere abstractions with no contextual significance, unless the teacher is able to provide a bridge, or scaffold from what is already known to such new learning. Art expression can provide this scaffolding simply by using pictures and symbols of relevant topics and issues. At MCI-J many students have such symbols already tattooed on their bodies. These tattoos, like other forms of art expression, are also symbolic, providing insight into one’s life. One could also make the point, as Kirkland (2009) does, that the reading and interpretation of tattoos is a form of literacy in itself. In his case study of Derrick and his tattooed body, Kirkland reminds us that the “tattoos are always speaking and commenting on life” (p. 387). Derrick’s tattoos represented his personal stories and experiences as an African-American man who had much to say on many topics. These topics—identity, tragedy, courage, sacrifice, and memoriam–were presented on a canvas of flesh for all to read. Kirkland’s observations and interviews with Derrick and his friends over a course of three years reinforced the notion that multiple forms of literacy exist separate from mainstream America and its educational instruction. He acknowledges the love of tattoo art as a form of literacy wherein a “deeply personal dimension” is recorded, emotionally reconciled and expressed, and then acted upon. Derrick’s tattoos provided him with a basis in which to comment on life and make meaning from it.

[8]For beginning ESL students, it is hard to put emotion into learning a second language. English is difficult to learn, especially if there is limited school literacy in the home language. Parts of speech and other grammar rules can be mere abstractions with no contextual significance, unless the teacher is able to provide a bridge, or scaffold from what is already known to such new learning. Art expression can provide this scaffolding simply by using pictures and symbols of relevant topics and issues. At MCI-J many students have such symbols already tattooed on their bodies. These tattoos, like other forms of art expression, are also symbolic, providing insight into one’s life. One could also make the point, as Kirkland (2009) does, that the reading and interpretation of tattoos is a form of literacy in itself. In his case study of Derrick and his tattooed body, Kirkland reminds us that the “tattoos are always speaking and commenting on life” (p. 387). Derrick’s tattoos represented his personal stories and experiences as an African-American man who had much to say on many topics. These topics—identity, tragedy, courage, sacrifice, and memoriam–were presented on a canvas of flesh for all to read. Kirkland’s observations and interviews with Derrick and his friends over a course of three years reinforced the notion that multiple forms of literacy exist separate from mainstream America and its educational instruction. He acknowledges the love of tattoo art as a form of literacy wherein a “deeply personal dimension” is recorded, emotionally reconciled and expressed, and then acted upon. Derrick’s tattoos provided him with a basis in which to comment on life and make meaning from it.

At MCI-J, questions from the instructor about personal symbols can provoke an emotional response. Although tattoos and tattoo paraphernalia are not allowed in prison, tattooing is a big part of prison life and tattoos in fresh ink are seen frequently. Men at MCI-J report that tattooing is a respected art form in prison, with good tattoo artists commanding esteem and admiration. Gell (1993), in his research on tattooing in Polynesia, notes that many of the tribal tattoos take on a life of their own. He writes of the organic nature of these tattoos– changing, growing, becoming an intermediary for some external vision or expression. Language, too, follows such a path–letters turn into words, words become sentences, and words and sentences morph into mental images as a story emerges. Some tattoos incorporate the same symbols seen in other artwork, for example, angels, crosses, alpha letters, spiders and webs, names, guns, skulls, marijuana leaves, and certain animals are all common images at MCI-J. Several students are also experienced in graffiti art, with many of the same symbols having social and urban messages. One inmate at MCI-J found his own tattooed designs so pleasurable and self-gratifying that he became addicted to seeking out unique and personal patterns in order to tell his story on his body. It became a challenge to seek the most creative design, and today his body—arms, legs, torso, neck, head—are entirely covered with tattoos, which he loves. This self expression is a story in itself as it chronicles the experiences of his life. These are the “literate acts” referred to by Kirkland (2009), and the reading thereof is a form of literacy which must be acknowledged today as a new dimension in learning. Kirkland challenges educators to see literacy in different forms, not just in print, but in a deliberate act of human expression and experience, such as those inscribed on flesh. Today, tattoos have gone mainstream as forms of self-expression and identity, and are found not just on inmates in prison and soldiers on military bases, but in middle America among older and young adults, women and men. Because of this popularity, the reading and interpretation of body art provides a road to critical literacy and captures the attention of reticent students who may not otherwise engage in traditional methods of instruction.

In DelliCarpini’s (2006) comments on correctional ESL programs across the country, she found that many correctional education programs for ESL students are designed for independent study, with ELLs working silently from a notebook, independently or with a tutor. This methodology is not effective for language learners, who require immediate feedback, spontaneous conversation, and interactive discussion about meaningful topics. The power of multiple literacies and visual art as pedagogy in a correctional classroom setting cannot be overlooked.

Student art serves a useful purpose in the classroom.

[9]My favorite artifacts from our classroom activities are the alphabetic representations made by my students, who took the first letter of their favorite person, place, or thing and made a complete set of 8” x “12” alphabet cards. Many of the designs used on the cards incorporated the same images as their body art. The results on the cards were astounding—beautiful letters, colors, and designs representing what were special to them. In turn, these cards became the introduction for lessons on parts of speech, starting with the nouns represented by the letter cards. The cards were large enough that they were set up around the room not just for admiration, but for contemplation. Not only did students learn the names of nouns, but they had visual cues when writing the words, also. I love these cards because they are permanent reminders of the artists and their talents. As students progressed to different classes and moved to other institutions, I found myself looking at the illustrations and their names written on the back of the cards. I remembered all of them—special people with something important to say. Their self-confidence about their abilities in literacy development began with illustrating letters of the alphabet and using these letters to spell words. Now many of them are in the advanced classes, writing paragraphs and studying to take the high school equivalency exams. Their success makes me proud.

[9]My favorite artifacts from our classroom activities are the alphabetic representations made by my students, who took the first letter of their favorite person, place, or thing and made a complete set of 8” x “12” alphabet cards. Many of the designs used on the cards incorporated the same images as their body art. The results on the cards were astounding—beautiful letters, colors, and designs representing what were special to them. In turn, these cards became the introduction for lessons on parts of speech, starting with the nouns represented by the letter cards. The cards were large enough that they were set up around the room not just for admiration, but for contemplation. Not only did students learn the names of nouns, but they had visual cues when writing the words, also. I love these cards because they are permanent reminders of the artists and their talents. As students progressed to different classes and moved to other institutions, I found myself looking at the illustrations and their names written on the back of the cards. I remembered all of them—special people with something important to say. Their self-confidence about their abilities in literacy development began with illustrating letters of the alphabet and using these letters to spell words. Now many of them are in the advanced classes, writing paragraphs and studying to take the high school equivalency exams. Their success makes me proud.

Conclusion

Learning in an academic setting is hard work, especially for those who do not come from  [10]environments where education and school were prioritized. Consequently, literacy instructors must use any means possible to entice students to a learning environment and literacy development, which may be expressed in many different forms. ESL students at MCI-J love to be involved in art activity in the classroom as is evidenced by low absenteeism, academic literacy promotions, and zero disciplinary problems. Using art engagement as a bridge to school, community, and personal literacies is successful for students as it captures the heart of those who struggle with traditional methods of (text-only) learning. It is this personal engagement that has provided energy and empowerment to Latino men learning English as a second language. By participating in the arts in classroom instruction, they are able to enhance their thoughts, and subsequently their verbal and written language development.

[10]environments where education and school were prioritized. Consequently, literacy instructors must use any means possible to entice students to a learning environment and literacy development, which may be expressed in many different forms. ESL students at MCI-J love to be involved in art activity in the classroom as is evidenced by low absenteeism, academic literacy promotions, and zero disciplinary problems. Using art engagement as a bridge to school, community, and personal literacies is successful for students as it captures the heart of those who struggle with traditional methods of (text-only) learning. It is this personal engagement that has provided energy and empowerment to Latino men learning English as a second language. By participating in the arts in classroom instruction, they are able to enhance their thoughts, and subsequently their verbal and written language development.

The policy information report for correctional education (Coley and Barton, 2006) explicitly states that [creative] “programs tailored to the prison population are more likely to succeed” (p. 20), success being determined initially by higher test scores and academic advancement, consequently by lower rates of recidivism. Similarly, the President’s Committee on Arts and Humanities (PCAH, 2011) advocates for and recommends nontraditional methods of pedagogy, specifically arts integration, in America’s schools. PCAH notes that participation in the arts increases academic performance and creative thinking skills. The integration of arts participation in correctional education is essential as it provides and encourages critical thinking, social discourse, personal engagement and expression, inquiry, discussion, multicultural awareness, and language development. For many inmates, such discourse will be the first time they have experienced and practiced any type of self reflection and dialogue.

Art stimulates language use in a most enjoyable, loving way by allowing for personal, expressive, and emotional perspectives, which provides rich and varied language results. Art gives us that visual language with which to verbalize our thoughts, feelings, and emotions. These feelings and emotions are cultural and personal in origin and reflect our experiences in life. By integrating personal histories, culture, and language into the curriculum, the instructor can foster critical thinking and critical literacy, even at beginning levels of language learning. This critical thinking is essential for correctional educational students who must learn new, nonviolent ways of coping with stress and new problem-solving techniques. As we teach inmates to embrace the idea of loving one’s neighbor, art provides that catalyst for appreciation, love, and respect. It provides a visual communicative resource through which real dialogue can occur, and real change can take place.

As I discovered over the years, my adult correctional students like to be engaged in activities that are visual or tactile—anything they can see, touch, or do provides motivation for learning and engagement (see Author, 2011 and 2014). The importance of a sustainable education cannot be overstated. Through real conversations about real issues, through dialogues with multicultural students, and in an environment where respect for others’ opinions is paramount, ESL students have learned that they can be positive agents of change for themselves, their families, and their communities. Art engagement is an excellent vehicle for a sustainable education and can be incorporated easily into the state benchmarks, including the new Common Core State Standards. My students have practiced and learned English by making cards for loved ones; drawing maps during a study of continents and countries; illustrating native holiday culture and historical facts on poster board; painting portraits of their homes in Central America and Mexico; and decorating our classroom with personal artistic expression. Although many of these artifacts were made years ago, they are still displayed in the classroom, and they continue to provoke an expressive response from old and new students alike.

References

Author, (2011). The success of total physical response in the adult ESL classroom.

Corrections Today. Feb./Mar. pp. 50-55.

Author (2014). Working toward literacy in correctional education ESL. Journal of

Research and Practice for Adult Literacy, Secondary, and Basic Education, 3(1), 38-43.

Coley, R. and Barton, P. (2006). Locked up and locked out: An educational

perspective on the U.S. prison population. ETS Policy Information Report.

New Jersey: Educational Testing Service.

Freire, P. (2010). Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York: Continuum International

Publishing Group.

DelliCarpini, M. (2006). Working with literacy-level English language learners in

correctional education settings: Issues, challenges and best practices. Journal of

Correctional Education, 57, 250-266.

Gallego, M.A., & Hollingsworth, S. (2000). Introduction: The idea of multiple

literacies. In M.A. Gallego & S. Hollingsworth (Eds.), What Counts as

Literacy: Challenging the School Standard, pp. 1-25. New York: Teachers

College.

Gell, A. (1993). Art and agency: An anthropological theory. Oxford:

Clarendon.

Kirkland, D.E. (2009). The skin we ink: Tattoos, literacy, and a new English

education. English Education 41, 375-393.

Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary, Tenth ed. (1994). Springfield: Merriam-

Webster, Inc.

Ovando, C., Combs, M., and Collier, V. (2006). Bilingual and ESL Classrooms.

Teaching in Multicultural Contexts. New York :McGraw Hill.

Pleasants, R.K. (2007). Teaching young men in correctional education: Issues and

interventions in male identity development. The Journal of Correctional

Education 58(3), 249-261.

President’s Committee on Arts and Humanities (PCAH) (2011). Re-investing in arts

education: Winning America’s future through creative schools. Retrieved

on January 15, 2012 from http://www.pcah.gov [11] .

Urrieta, L. Jr. and Quach, L. (2000). My language speaks of me: Transmutational

identities in L2 acquisition. The High School Journal, 84, 26-35.

Vocke, K. (2004). Final thoughts: Teaching reading, teaching readers.

Language Arts Journal of Michigan, 20, 2, 75-77.

Wesley, S. (2007). Multicultural diversity: Learning through the arts.

New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, 116, 13-23.

Susanne Gardner