Iwan Rao JSE Fall 2017 General PDF [1]

LINK: December 2017 General Issue: Curriculum and Change Table of Contents [2]

An increasing number of educational institutions consider themselves to be green schools. A critical event that fueled the Green School movement was the report “Caring for Our Future” commonly referred to as the Brundtland Report (Brundtland et al., 1987). The Report called for a global awakening to preserve the Earth’s resources through shifting our behavior to be more sustainable and responsible, not only for today’s world’s population, but also for the future generation. It called for an action plan to face common challenges in: population and human resources; food security; species and ecosystems; energy; industry; and urbanization.

As a response to Brundtland Report (Brundtland et al., 1987) report, the World’s leading environmental organizations, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), and the World-Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) proposed a new strategy for sustainable living in its report, Caring for the Earth (IUCN, UNEP, and WWF, 1991). The strategy included promoting adherence to a new ethic for sustainable living and supporting the translation of articulated principles into practice. These principles are concerned with respect and care for nature (ecological sustainability); the quality of human life; preserving biodiversity; changing ecological practices; supporting communities to care for their own environment and having national frameworks that integrate development and conservation (IUCN, UNEP, and WWF, 1991).

Global interest in sustainable development increased after the Brundtland Report. In 1992, the United Nation’s Agenda 21, signed at the Earth Summit at Rio de Janeiro, stated that: “The overall human settlement objective is to improve the social, economic, and environmental quality of human settlements and the living and working environments of all people….” (UN, 1992). The Earth Summit also introduced the term Education for Sustainable Development (ESD). Variants of the term are commonly used including “Educational for Sustainable Living” (IUCN, UNEP, & WWF, 2009); 2); “Education for Sustainability” (National Forum on partnership Supporting Education about the Environment USA, 1996); “Education for a Sustainable Future” (UNESCO, 1997); “Environmental Education for Sustainability”, “Environmental Education”; and “Developmental Education” (Fien & Tilburry, 2002).

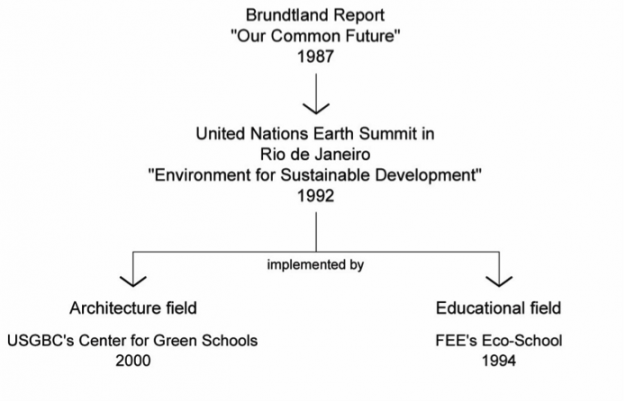

One of the many outcomes from the further development of ESD was the establishment of schools that embrace sustainable approaches or the Green School Movement. Similar to the ESD term, the Green School term suffers from debatable (Moore, 2008) and negotiable meanings (Iwan, 2013). That stated Green Schools are perceived as an educational vehicle that carries the mission of ESD. Such an understanding positions Green Schools as the type of school that presumably supports the 17 Goals for Sustainable Development (United Nations (UN), 2015). The responses toward the ESD’s direction from the educational field was immediate, with the launching of Eco-Schools by the Foundation for Environmental Education (FEEE) in Europe in 1994 and the establishment of the United States Green Building Council in 1993. The later created the USGBC’s Center for Green School in 2000 (Center for Green School, 2016). Established in 1981 to serve the European continent, the FEEE expanded its scope to be a global NGO when it simplified its acronym to FEE in 2001. The USGBC also expanded its scope by pioneering the establishment of the World Green Building Council (World GBC) in 2002.

The FEE and World GBC have become the two major pioneering international ‘green’ NGOs. The FEE Global focuses on the educational aspect of ESD and the World GBC on building and environment aspects of ESD. The FEE continues with its Eco-School program, which today claims to have 49,000 school participants in 64 countries. The USGBC’s Center for Green Schools provided the major resources for the establishment of the Global Coalition for Green Schools in 2013 (Shelter, 2013), a subsidiary chapter of the World GBC. The historical roots of the Green School movements in the fields of architecture and education are illustrated below.

The Green School movement has also been promoted by other institutions and some countries have developed their own versions of Green Schools reflecting their interpretations of this concept. The following section specifically explores understandings of the notion of a Green School against the background of parallel movements in the fields of both education and built-environment.

Green Schools and Green Education

The terms Green School and Green Education are often used interchangeably. Scholars and laymen alike continuously adopt Green Education and similar terms to describe both formal and informal environmental studies. A simple activity such as introducing children to recycling can also be perceived as Green Education, since it instills awareness in people about the effects of their actions on the Earth and on other people (Pancheri-Ambrose & Tristchler-Scali, 2013). The most influential international institution focusing on developing Green Education is the FEE mentioned above. It launched the largest sustainable school program in the world (Eco-Schools, 2014) with the aim of empowering students to be agents of a sustainable world by engaging them in fun, action-oriented learning activities (Eco-Schools, 2014). Ireland has adopted a nation-wide national environmental education program based on Eco-schools. The country has adopted an Eco-School Green Curriculum that integrates the following six key themes: (i) Litter and Waste; (ii) Energy; (iii) Water; (iv) Travel; (v) Bio-diversity; and (vi) Global Citizenship. More than 3,700 primary, secondary, and special schools in Ireland participate in this program, and over 2,785 schools have been awarded Green Flags (Green Schools Ireland, 2016).

The World Organization for Early Childhood Education (OMEP) has taken the lead in promoting ESD in the early years. Clearly, it is important to introduce sustainable concepts to young children in order to promote life-long eco-friendly practices (Engdahl, 2015). OMEP, however, can be considered a late-comer in responding to the ESD in comparison to FEE and USGBC. OMEP developed the Environment Rating Scale for Sustainable Development in Early Childhood (ERS-SDEC) (Pramling-Samuelsson, Siraj-Blatchford, & Park, 2013), and conducted a World Project on ESD for the Early Years (Engdahl, 2015). It also published a book on promoting ESD during the early years (Siraj-Blatchford, Smith, & Pramling Samuelsson, 2016). Studies conducted under the auspices of OMEP have provided evidence that young children have knowledge about the Earth, thoughts about environmental issues, and are able to articulate their thinking about sustainable development (Engdahl, 2015). These findings further point to the necessity of promoting environmental awareness in young children. OMEP, however, has not launched any Eco-Schools or Green Preschools. On the other hand, it promote ESD activities for young children

The Built Environment and Green Education

A Green School building is expected to reduce environmental problems and increase the well-being of a school’s stakeholders (Kobet, 2009). High performance Green Buildings provide healthy environments for children because they follow a set of architectural criteria to improve the effectiveness of daytime lighting and the indoor air quality. Indoor and outdoor air pollution are assumed to aggravate the severity of asthma symptoms in children. Exposure to air pollution is of special concern for children, because their immune systems and lungs are not fully developed (Schwartz, 2004). Since building design affects the indoor air quality it is particularly important for architects to have thorough knowledge of how to create healthy environments for young children.

When school grounds are greened, students benefit from increased play opportunities (Dyment, 2005), healthier and safer outdoor environments (Titman, 1994; Cheskey, 2001; Bell & Dyment, 2006; Boldermann et al., 2006), enhanced learning opportunities (Centre for Ecoliteracy, 1999; Bell, 2001b), increased engagement with the natural environment (Harvey, 1989; Nabhan & Trimble, 1994; Hutchison, 1998; Bell, 2001a; Malone and Tranter, 2003 a, b), and improved academic achievement (Lieberman & Hoody, 1998). Furthermore, the Green School facilities can also be considered as an extension of a Green Curriculum (Gutter, 2009). Therefore, constructing Green Buildings that are certified through a set of strict criteria is not a luxury, but a necessity to ensure children’s health and well-being.

The Conceptualization of a Green School

The Green School concept is defined differently across nations, as countries vary in their understandings and interpretations. However, the pace of its propagation remains strong, due to the various competitions held by green institutions (public, private, or NGOs). The recent popularity of the establishment of the Green Schools has resulted in range of diverse terms being used to refer to Green Schools. These include: Eco-Schools, Sustainable Schools, Green School-Building, Green School-Environment, and Green School-Curriculum. Iwan (2013) has argued that the loose interpretations of Green Schools could be seen as opportunities in this fertile field.

The Green School movement is organic and progressive within the context of ESD, as illustrated by the following examples from the United States and China. The United States Green Building Council (USGBC), through its Center for Green Schools, described the Green School as a healthy environment that is conducive to learning, while saving energy, resources, and money. This interpretation appears to associate the Green School concept with schools designed physically to meet the Green Building criteria (the ‘hardware’ part of the Green School). This view has evolved over time, with the Center for Green Schools eventually incorporating eco-literacy (the ‘software’ part of the Green School) in their mission.

The Green School concept in China was initially introduced by the State Environmental Protection Administration (SEPA), which loosely defines a Green School as one that enhances its management processes, updates its teaching tools, and reduces its operating expenses by improving its energy efficiency, gradually moving toward sustainable development (Zhang, 2004). A green institution in Hong Kong, Environmental Campaign Committee-Hong Kong (ECC-HK), organized numerous local environmental activities including the Green School award (Environmental Campaign Committee, 2013). The objectives of ECC-HK Green School Award are to encourage schools to: formulate a school environmental policy and environmental management plan for a ‘Green School’; enhance environmental awareness, develop environmentally-friendly attitudes, and promote green practices among school managers, teachers, non-teaching staff, students, and their parents.

Despite the varying notions of what constitutes a green institution, there have not been any studies that have reviewed stakeholders’ views of Green Schools. In this study, the stakeholders are principals, teachers, and parents from award-winning preschools. These people experience Green School on a daily basis. Because these stakeholders influence the policies and practices within Green Schools, their views are considered important.

Research Questions

There is a dearth of empirical studies detailing people’s views on the Green School concept and the relationship between green building construction and a green curriculum. This qualitative research was designed to produce empirical data by interviewing stakeholders (principals, teachers, and parents) from three award-winning green preschools in Bali, Berkeley, and Hong Kong, The following research questions were created to guide the study:

- What are the stakeholders’ understandings of a Green School concept? Green Education and Green Building were explored specifically.

- If resources are limited, do stakeholders prefer having students taught under a Green Curriculum or being located inside a Green Building?

Method

Settings

The search for exemplar award-winning Green Schools was conducted in 2012. Award-winning Green Schools were chosen as they were assumed to reflect the highest standards of commitment to ESD, on the part of the school stakeholders (represented by principals, teachers, and parents). Given the debatable meaning of the Green School (Moore, 2008) and the limited numbers of award-winning Green Preschools, we selected Green Schools that received awards from two different organizations: the USGBC, and the ECC-HK. We were aware that these organizations may use slightly different criteria to judge schools. Purposeful sampling was used to select preschools in three different locations: Bali, a developing region in a developing country (to represent the East); Berkeley, a developed city in a developed country (to represent the West); and Hong Kong, a developed city in a developing country (to represent the meeting point of the East and the West). One classroom, serving four- to five-year-olds, from each school was selected as the representative unit of analysis.

Bali, an island covering 5,632.86 squares kilometers with a population in 2012 of 3.16 million, is a popular tourist destination. Preschool A is a part of a larger pre-K-12 campus that won the USGBC’s Greenest School on Earth award in 2012. Berkeley, a city covering 45.84 squares kilometers, with a population of 115,301 in 2012, is well-known as the site of the University of California, Berkeley. Preschool B was built to care for the children of the university staff, faculty, and students, and is within a 10-minute walking distance from the university main campus. The building won a LEED Silver Award in 2006 from the USGBC. Hong Kong, known as Asia’s World City, is a densely populated region with population of 1,104 square kilometer area and with a population of 7.155 million in 2012. Preschool C received an Outstanding Green Preschool Award in 2012, from the Environmental Campaign Committee of Hong Kong (ECC-HK).

Participants

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with a total of 21 participants (Table 1). Principals’ educational qualifications ranged from Bachelor’s to Master’s degrees, teachers’ qualifications ranged from high school to Master’s degrees, while parents’ educational background ranged from undergraduate to postgraduate levels. The observed classroom in Bali accommodated two teachers and 16 children, Berkeley’s accommodated three teachers and 16 children, and Hong Kong’s accommodated two teachers and 28 children. One can see there was an imbalance on teacher-student ratios, with Preschool A (1:8), Preschool B (1:3), and Preschool C (1:14).

Table 1. Interview Participants

| Participants | Preschool A | Preschool B | Preschool C | Total |

| Principals | 1 male principal | 1 male principal | 1 female principal | 3 |

| Teachers | 2 female teachers | 3 female teachers | 2 female teachers | 7 |

| Parents | 1 male parent1 female parent | 4 female parents3 male parents | 1 male parent1 female parent | 11 |

| Total | 5 | 11 | 5 | 21 |

Procedure

All data were collected on-site in Bali, Berkeley, and Hong Kong within a 10-month period. Semi-structured interviews were chosen to elicit a deep and nuanced understanding of the stakeholders’ views of the Green School concept, including its variations, such as Green Education and Green Building. A specific question was asked regarding their preferences related to children being taught under a Green Curriculum or inside a Green Building if resources were limited. Each participant was interviewed in an individual session that was audiotaped. The interviews lasted between 45 to 120 minutes.

Results

Data Management. The first author transcribed the interview results and developed a coding scheme based on Auerbach and Silverstein (2003). The data analysis process was performed critically following the seven major steps: raw text, relevant text, repeating ideas, themes, theoretical constructs, theoretical narrative, and research concerns. Four key iterative steps were followed: mechanics (transcription), data immersion (reading and re-reading transcripts), generation of initial codes (initial pattern recognition), and categorization of the themes and constructs, while the percentage of recurring comments within each interview were recorded. Certain interesting, short direct quotations were taken from participants verbatim to reflect their original voices.

Inter-Rater Reliability. In order to establish inter-rater reliability for the interview transcripts, a Ph.D. candidate in the field of education and with a psychology background independently coded 20% of the transcripts. An inter-rater agreement of 89% was reached; disagreements, which mostly arose from the two coders’ different academic backgrounds, were discussed to a satisfactory resolution. This exercise helped to minimize the first author’s personal bias.

The results in this section are presented in the form of tables followed by explanations. The percentages of different comments that occurred during the interviews were extracted, coded, and tabulated, to capture the perceptions of the stakeholders from Preschool A (Bali), B (Berkeley), and C (Hong Kong) about: (i) The Green School (Table 2); (ii) The Green Education (Table 3); and (iii) The Green Building (Table 4).

Stakeholders’ Views on Green School

Table 2. Comments Displaying Stakeholders’ Understanding of the Green School

| The Concept ofThe Green School | Preschool A(Bali) | Preschool B(Berkeley) | Preschool C(Hong Kong) |

| Principals’ Comments | It is a progressive institution(37.5%)It creates a successful model to inspire others (25%)It is a holisticInternational school(12.5%)

It gives different approaches to education (12.5%) It has students from over 40 nationalities (12.5%) |

It means how we teach children about the environment (50%)It means using less resources from the environment to build the school (50%) | It involves everyone who is doing it (25%)It refers to the number of plants in my school (25%)This idea comes from curriculum and environment (25%)A ‘Green School’ idea should penetrate into everyone’s minds and hearts (25%) |

| Total | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| Teachers’ Comments | It aims to connect children with nature (37.5%)Teachers love green schools and so do the children (18.75%)It teaches children to be compassionate human beings (18.75%)It is teachers’ second home (12.5%)It encourages students to think outside the box (6.25%)It is an experiment and it is still evolving (6.25%) | It does not consume too much energy or environmentally friendly (57.15%)This school is not promotedas a ‘Green School’ (28.57%)This school tries to be a green school (14.28%) | It is environmentally friendly (66.66%)It is decorating my environment with recycled things (33.33%) |

| Total | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| Parents’ Comments | An institution that wants to change the current education system (33.33%)Outdoor and nature based-learning (33.33%)A school that is trying to offer learning experience that is holistic, personal, interpersonal, kinesthetic, and intellectual (33.33%) | It is a green building (33.33%)It is one that participates in recycling, planting, reusing, and composing (22.22%)It is the same with green education (22.22%)It is about natural lighting, a lot of windows, and environmentally friendly (11.11%)This preschool is a ‘Green School’ in terms of facilities (11.11%) | It teaches children to recycle, reuse, and reduce waste (environment protection) (71.42%)It is similar with green education (28.57%) |

| Total | 100% | 100% | 100% |

Preschool A. The interviews with the stakeholders from Preschool A demonstrated the following: (i) 37.5% of the principals’ comments referred to a Green School as a progressive institution; (ii) 37.5% of the teachers’ comments referred to a Green School as a means to connect children with nature; and (iii) 33.33% of the parents’ comments referred to a Green School as an institution to change the current education system. One of the notable comments made by an interviewee was:

“Green School is a progressive, holistic, international school sets among in a natural setting and build in a sustainable material as part of vision and mission to keep kids connected to the environment and to the local culture.”

Principal, Green Preschool A

The aforesaid results represent the majority comments from Preschool A’s stakeholders, indicating that they mainly perceived a Green School as an Institution.

Preschool B. Interviews with the stakeholders from Preschool B about their understanding of Green School demonstrated the following: (i) 50% of the principal’s comments referred to a Green School as a means of using less resources from the environment to build the school (an understanding of green school as a green building) while the other 50% discussed a Green School as the way we teach children about the environment (an understanding of green school as green curriculum); (ii) 57.15% of the teachers’ comments referred to a Green School as a school that does not consume too much energy or is environmentally friendly; and (iii) 33.33% of the parents’ comments referred to a Green School as a Green Building. One of the notable comments was:

“A Green School is a green building. So, whether or not it is a green house or a green

library, the building that has been constructed with an environmental mind so using

less resources or having more windows and skylights so that you don’t have to turn

light on all the time. This building is a pleasant space to be in, it just feels very friendly

and happy and I think a big part of it is the natural light”

Parent, Green Preschool B

The aforesaid results represent the majority comments from Preschool B’s stakeholders, indicating that they mainly perceived a Green School as a Green Building.

Preschool C. Interviews with the stakeholders from Preschool C about their understanding of Green School demonstrated the following: (i) four different comments related to the concept and curriculum of Green School were equally shared with each comment weighing 25% (Table 2); (ii) 66.66% of the teachers’ comments referred to a Green School as environmentally friendly; and (iii) 71.24% of the parents’ comments referred to a Green School as an institution that teaches children to recycle, reuse, and reduce waste (environmental protection). One of the notable comments was:

“A Green School is a school that implements a lot of curriculum that is environmentally friendly. The school has a lot of decorations of recycling things or a lot of plantation”.

Teacher, Green Preschool C

These results represent the majority comments from Preschool C’s stakeholders, indicating that they mainly perceived a Green School as a Green Curriculum.

Stakeholders’ Views on Green Education

Table 3. Stakeholders’ Understanding of the Green Education

| The concept of “Green Education” | Preschool A(Bali) | Preschool B(Berkeley) | Preschool C(Hong Kong) |

| Principals’ Comments | Understanding the significance of fresh water, eco-system, and being out in the garden (31.25%)It is what we do here through green studies (25%)Education that is sustainable (18.75%)It has a similar meaning to ‘Green School’ (6.25%)Looking at the world through green lenses (6.25%)‘Green Education’ can happen anywhere (6.25%)

It is about how we connect with the environment (6.25%) |

Children can learn early about sustainability (50%)A green school and green education is combined (16.66%)Teachers buy used toys to be environmentally friendly (16.66%)I am trying to have children consume organic food (16.66%) | ‘Green Education’ is education that goes for everybody (staff, parents, and children) (83.33%)‘Green Education’ is the same as a ‘Green School’ (16.66%) |

| Total | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| Teachers’ comments | A school that connects the lesson with outdoor activities (bonding with the nature) (30.30%)We have green studies every day (21.21%)A school that teaches students to compose and reduce the use of plastic (21.21%)‘Green Education’ is through hands-on experience (15.15%)‘Green Education’ is about promoting sustainability (12.12%) | ‘Green Education’ is teaching sustainability: reduce, reuse, recycle, ecology, and environment (72.72%)‘Green Education’ is as similar as ‘Green School’ (9.093%)We need to educate children about green education (9.093%)It is to encourage consuming organic food (9.093%) | An education to nurture children with environmentally friendly attitude, such as making new things with recycled materials (60%)Teachers as role models to show children how to protect the earth (e.g. turn off the light, recycling, etc. (20%)A ‘Green School’ is similar to ‘Green Education’ (20%) |

| Total | 100 % | 100 % | 100 % |

| Parents’ comments | Parents are unclear about the meaning of ‘green education’ (50%)‘Green Education’ is about sustainability or how to preserve the planet (20%)‘Green Education’ equal with green school (10%)The school offers a lot of additional information for parents about ‘green education’ (10%)‘Green Education’ includes learning about our inner world (10%) | Parents are unclear about the meaning of ‘Green Education’ (43.47%)It is important for my child to learn about sustainability (30.43%)‘Green Education’ is the teaching about sustainability(26.1%) | Parents are somewhat familiar with ‘Green Education’ (36.36%)Our school promotes ‘green education’ through campaign (recycle paper, bring their own lunch box, etc.) (36.36%)It is important for my children to learn about sustainability (18.18%)It is the responsibility of the government to promote ‘Green Education’ (9.09%) |

| Total | 100% | 100% | 100% |

Preschool A. Interviews with stakeholders from Preschool A about their understanding of the Green Education suggested that: (i) 31.25% of the principal’s comments referred to the Green Education as understanding about the significance of fresh water, eco-systems, and being out in the garden; (ii) 30.30% of the teachers’ comments referred to Green Education as a school that connects the lesson with outdoor activities such as bonding with Nature; and (iii) 50% of parents were unclear about the meaning of Green Education.

“Green Education is what takes place in a Green School so they are similar. In my

opinion that is learning about the Nature and using Nature as your teacher and your guide”.

Teacher, Green Preschool C

In summary, educators understood Green Education as the act of learning in Nature while parents seemed unclear about its meaning.

Preschool B. Interviews with stakeholders’ from Preschool B indicated: (i) 50% of the principals’ comments showed that children can learn early about sustainability; (ii) 72.72% of the teachers’ comments suggested that Green Education is about teaching sustainability related to the 3Rs (reduce, reuse, and recycle), along with the teaching of ecology and environment; and (iii) 43.47% of the parents’ comments showed that they were unclear about the meaning of Green Education. These comments highlight the different understandings between educators (principal and teachers) and parents in Preschool B. The teachers considered Green Education as being similar to sustainable teaching, while the parents seemed unclear about the meaning and leaning toward the understanding of Green School as a Green Building:

“I always thought that green education is learning how to build a green building.”

Parent, Green Preschool B

Preschool C. In Preschool C the stakeholders’ interviews demonstrated the following: (i) 83.3% of the principal’s comments referred to the Green Education as something in which all preschool stakeholders, including staff, parents, and children, should know; (ii) 60% of the teachers’ comments referred to it as an education that provides children with environmentally friendly attitudes, such as making new things with recycled materials; and (iii) 36.36% of the parents’ comments suggested that they were only somewhat familiar with the understanding of the Green Education, while another 36.36% expressed the belief that Preschool C had promoted Green Education through green campaigns (e.g. asking students to bring recycled papers for artwork).

“Green education means teachers can teach children the behavior or the attitude to protect our earth, the concept of how to recycle, and what we can do to make our earth a better place.”

Principal, Green Preschool C

These results indicated that the stakeholders’ understanding of the Green Education was initiated mainly by the principal, who conveyed this message through various environmental activities. Similar to Preschool A and B in Preschool C, parents’ participants were also those who have least understanding about this concept.

Stakeholders’ Views on Green Building Concept

Table 4. Stakeholders’ Understanding of the Green Building

| The concept of the Green Building | Preschool A(Bali) | Preschool B(Berkeley) | Preschool C(Hong Kong) |

| Principals’ comments | The bamboo buildings give an understanding of sustainability because it will be decomposed after we use it (71.42%)Curriculum and building blend together (28.58%) | I enjoy being in a green building (40%)The green building award for this preschool meant a lot for City of Berkeley (20%)I do not know what contributes to the green building awards selection. (20%)The more you are in a green building, the more you want to talk about being green (20%) | The building of the school is more natural (100%) |

| Total | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| Teachers’ comments | The bamboo school gives an opportunity for teachable moments at any time (25%)The sustainable building is important because it is the first sight that people see (25%)This school building has no walls and it influences the way of learning (25%)The building does not have to be bamboo but it needs to have natural light and it should have access to outdoor environment (25%) | I do not know why this building won a green award.(33.33%)I do not see the impact of the green building on children(33.33%)I know this is a green building (25%)The environment contributed to the green building award (8.33%) | I do not know a green building (100%) |

| Total | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| Parents’ comments | A green building is very important (50%)In a bamboo school, you are preaching what you teach where sustainability become parts of your life (50%) | They mentioned this preschool is a green building(42.85%)The fact that this preschool is a green building motivated me to enroll my child(28.57%)A green building is better than the others that are not (14.28%)I know green buildings (14.28%) | There were no comments from parents (100%) |

| Total | 100% | 100% | 100% |

Preschool A. When the stakeholders from Preschool A were interviewed about their understanding of a Green Building; the following patterns emerged: (i) 71.42% of the principals’ comments indicated that they used bamboo as a sustainable building material because it would decompose after use; (ii) there were four different themes of teachers’ comments, but they all indicated that they had learnt about green building because of the use of sustainable materials in the building (Table 4); and (iii) 50% of the parents’ comments indicated that they understood the importance of green buildings, while the other 50% of parents’ comments showed that they believed a bamboo building is an effective way to convey sustainability message because they could experience being in a green building as part of their daily life. These results show-cased that the use of bamboo building material was an effective way for the stakeholders in Preschool A to grasp the importance and the idea of a green building and how it relates to sustainability.

“The building material is bamboo and open, it gives you a cultural feeling of space that is surrounded by garden, it gives you an understanding of the bases of sustainability around the school. The environment opens up children’s mind even in a sub-conscious way of the need to be sustainable such as solar panel, living-food-lab, coconut trees, garden, water, and the vortex.”

Principal, Green Preschool A

Preschool B. Interviews with the stakeholders of Preschool B indicated their understanding of a Green Building as follows: (i) 40% of the principal’s comments showed that he enjoyed being in Preschool B because it was a green building; (ii) there was a different understanding between teachers and parents because 33.33% of the teachers’ comments indicated they did not understand why Preschool B had won awards and 33.33% indicated that they did not see the impact of the green building on children, while (iii) 42.85% of the parents’ comments indicated that they knew Preschool B as a green building because they had been told about it by the staff.

“The school staff mentioned to us that the Preschool is a Green Building before we enroll our children here.”

Parent, Green Preschool B

It is clear that the Principal seemed to be more knowledgeable about the green building, while the teachers and parents seemed to be unaware of what a green building meant and why Preschool B had won a green building award.

Preschool C. The Preschool C stakeholders commented as follows: (i) The Principal’s comments indicated that a Green Building is a school that is more natural; (ii) the teachers’ comments indicated that they did not know what a Green Building is; and (iii) the parents had no comments about a Green Building. Aside from the principal, the stakeholders of Preschool C seemed to be unclear about the meaning of a Green Building. The Principal did not consider the school to be a Green Building; however, she took the initiative to make the school to look more natural.

“You can see we used a lot of woods. This is my idea because I like the natural feeling in the school.”

Principal, Green Preschool C

Green Building versus Green Curriculum

The responses from the preschool stakeholders in all three contexts (despite the different geographical locations) suggested that they preferred to have children taught using a green curriculum to their being taught in a Green Building. The following direct quotes illuminated stakeholders’ preference for a green curriculum:

“The building is beautiful and built with sustainable material that shows commitment to green living. Essentially, the bamboo building can literally go back to earth if we abandon it today. But, for me it is really the ‘green curriculum’ that matters. It is the ethos, it is the way how the green curriculum was delivered, it is the infusion of the art and the importance that we play as a holistic ‘green school’ that it is just as important to stimulate the body, as it is the mind, as it is the internal conversation that children have with themselves as well as the social interaction. I would say ‘green pedagogy’ and ‘green curriculum’ is more important than the architecture, however, a green building is good to represent what is possible to be built in certain environment.”

Principal, Green Preschool A

“I think it should be the curriculum, because you are influencing their future, and you are educating the children, whereas right now, we are in a green building, but it is not necessarily impacting their lives, so I definitely choose the green curriculum.”

Teacher, Green Preschool B

“Green education comes first before green buildings. However, it is important for the government to promote both.”

Parent, Green Preschool C

Principals’, teachers’, and parents’ responses showed their preference for Green Curriculum over Green Building.

Discussion

There is a critical need to understand the perceptions of stakeholders, because they have first-hand experiences in the Green Schools. Here, we discuss the results presented above, based on the two research questions posed to guide this research: 1) What are the stakeholders’ understanding of the Green School concept? What are their understanding of the derivatives of Green School such as Green Education and Green Building? and 2) If resources are limited, do stakeholders prefer having students taught under a Green Curriculum or being located inside a Green Building?

The Green School Manifestation: Stakeholders’ Perceptions

The terms Green School and Green Education were understood as similar and were used interchangeably by stakeholders regardless of culture. Minor differences regarding the understanding of Green Education were noticed, with Preschool A’s stakeholders viewing it as hands-on experiences; Preschool B’s stakeholders viewing it as a practical action-oriented approach and another stakeholder considering it as an education to build a Green Building; and Preschool C’s stakeholders viewing it as an abstract concept to protect the Earth for everyone.

The stakeholders in Preschool A had a notion of a Green School as an institutional entity. This is reflected in the name of Preschool A, which is consistent with the nature of the ‘green’ practice carried out in the school. The holistic approach of Preschool A to bring in the concept of a Green School in all aspects, such as the usage of renewable building material (bamboo), the incorporation of green studies into their overall curriculum, and the efforts to generate clean energy on site by installing the photovoltaic panels and micro hydro vortex in the school complex, have successfully conveyed the message to its stakeholders that the school set the bar of a Green School at the highest level. The stakeholders had a clear understanding regarding the mission statement of Preschool A, that is a community of learners aiming to make our world sustainable. Principals, teachers, and parents alike saw Preschool A as a school institution promoting green living. Preschool A building features an alang-alang (blady grass/imperata cylindrica) roof, with no walls and no doors, and the simplest of natural building materials (e.g., bamboo) have been used, which communicates to the stakeholders that it is a Green Building. The stakeholders seemed to be aware of the benefits of a Green Building. The stakeholders expressed the belief that the educational approach is to experience a connection with the Nature. They viewed a Green School as a sustainable building that integrates and becomes the extension of learning, which is consistent with the literature (Kobet, 2009 and Gutter, 2009).

The majority of stakeholders in Preschool B defined a Green School as a Green Building. This Preschool won a Green Building award and many of the stakeholders were made aware of this. However, the teachers and parents did not seem to appreciate it. 33.33% of the teachers in Preschool B did not know why the building had won a green award, and did not believe that being inside a Green Building would have any impact on the children. The responses from the stakeholders in Preschool B were mixed in regards to whether a Green School also means teaching children about environmental consciousness, or it is about a school that does not consume too much energy; some teachers even doubted whether their school can be considered as a Green School. As Preschool B was the first preschool to win the USGBC’s prestigious LEED Silver Award (Green Building), it is unfortunate that no action has been taken to educate the stakeholders about the significance of Green Buildings.

Stakeholders in Preschool C associated a Green School with a broad concept of environmental education where everyone should be on-board to provide support. The stakeholders viewed a Green School as a Green Curriculum, because they won an Outstanding Green Preschool Award attributed to their superb environmental awareness curriculum. It was observed that the Principal of Preschool C was the driver of the Green School movement, while the teachers could be seen as the executors of this school’s movement in implementing the Green Curriculum and the parents were the participants. Teachers from Preschool C had not acquired any understanding about Green Buildings. Preschool C building was not considered to be a Green Building. Therefore, the stakeholders’ ignorance of the concept is somewhat understandable.

Stakeholders’ Preference for a Green Curriculum over a Green Building

The interview data revealed that the stakeholders preferred children to be educated under a Green Curriculum, rather than simply being inside a Green Building, if resources are limited. This gives a valuable insight that can be used as evidence to support the recent ESD movement from international NGOs (e.g., United Nation Children’s Fund/UNICEF, United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization/UNESCO). UNESCO (2005) just completed its UN Decade of Education for Sustainable Development (2005-2014), which calls for a reorientation – at all levels and in all phases of education – to increase participation and involvement in ESD and its three pillars, which recognize the environmental, social/cultural, and economic/political dimensions of the learning process (Hopkins & McKeown, 2002). In early childhood, OMEP has strongly suggested that ESD should be a driver for quality education (Engdahl, 2015).

Therefore, more effort, resources, and financial investment should be put into the development of a ‘green curriculum’ within the context of ESD goals. Ideally, a Green Curriculum can be incorporated as part of the government’s educational agenda, much like the case of Ireland’s promotion of its Eco-Schools scheme. This presumably will require efforts from international United Nation bodies (e.g., UNICEF, UNESCO, United Nations Environment Program/UNEP) to educate governments to understand the criticality of promoting ‘green curriculum’. However, it is understood that each school needs to be given its own flexibility to tailor-made Green School curricula according to their distinct situations. Educators should be more creative in making the broader ESD vision relevant to local curricula (Hopkins & McKeown, 2002), regardless of the challenges involved therein. This finding is crucial because it alerts educators and policy makers in different parts of the world to the need to emphasize the development of the Green Curriculum, or to incorporate green studies into existing curricula.

Limitations

Researching a recently progressive movement such as the Green School (a new sustainable school phenomenon that mostly popularized by USGBC) requires a lot of time, effort, and financial resources, which unfortunately are limited. Given the novelty of the Green School research, particularly in the context of ECE, it was difficult to find award-winning preschool participants due to the scarcity of such schools. The participating schools were recipients of awards from either the USGBC or the ECC-HK. The three preschools were selected because they are the pioneers of the Green School, either in the building design, curriculum approach, or both. The authors acknowledge that parent participation in Preschool A (Bali) and Preschool C (Hong Kong) was lower than in Preschool B (Berkeley). This can be attributed to parents in Preschool B (Berkeley) being relatively more educated and better understanding the value of research in which many of them actively participated. Teacher and principal participation in all the three schools was 100%. This study was also limited by the lack of child observation because the schools did not give consent to videotape the children. A further limitation was the absence of interviews with green school experts because of the limited time and resources.

Future Directions

Future Green School research should look deeper into the potential impacts of the Green School in our society, in transforming people’s thinking and behaviors to care for the Earth. Future research also should look more into the curriculum of the Green School and how it can support the goals of international organizations such as the United Nations. If it is possible, future research should involve child participants and solicit their views about Green Schools.

Conclusion

Responses from the stakeholders in these three award-winning Green Schools indicate whether these institutions have successfully implemented their views of the Green School concept to the front-end users. We predict that the variety of understandings of the Green School – whether from the grassroots level (front-line stakeholders) or from the top level (various local and international institutions) – will continue to exist, because its nature is organic and expanding.

Our own operational definition of the Green School is the following: A school with a holistic philosophy and commitment that: (i) provide a healthy environment for its stakeholders through following the criteria of any of their local or international green building institutions and recognized by this institution with certain certification, (ii) that educate its stakeholders with environmental awareness with hands-on activities along with practical knowledge that are embedded in a singular or multiple subjects of the school’s curriculum and (iii) that include its neighborhood on this global mission to preserve the earth’s resources through promoting various ‘green’ campaigns and/or joining different ‘green’ competition.

Despite the various degrees of people’s understanding about sustainability, any efforts aimed to promote the Green School, whether in construction or curriculum development, would be a positive step. Educating schools’ stakeholders about the benefits of the Green School is considered to be critical to building a community that can support ‘green’ visions. Furthermore, it is also important to promote sustainable life-style within the school community. This study highlighted the need to develop and provide a Green Curriculum for preschool children, as we acknowledge that the early years are the foundation for life-long learning. It is crucial to educate young children about environmental issues in order to nurture their empathy for the environment, to learn how to live in harmony with it, and to eventually develop interests and skills to protect it.

Providing healthy environments for children through constructing Green Buildings will have long-term benefits, given the fact that children’s physical bodies are more vulnerable than those of adults’. The stakeholders in this research, however, have emphasized adopting a Green Curriculum above children being taught in a Green Building. This, in turn, should draw educators’ attention to the need to develop the content of Green Curricula, particularly for the early years. This finding should also help policy makers and investors to prioritize resources for future development of Green School, where more funding should be pour out to develop Green Curriculum instead of simply pushing the agenda to construct a Green Building. If funding is sufficient, it would be ideal to construct Green Building and also to incorporate Green Curriculum. When Green Curricula and Green Buildings co-exist, children get the best of both worlds because they are not only learning inside healthy buildings, but also the Green Building can be used as the extension of the Green Curriculum.

Practical suggestions based on this research include creating appropriate green studies through training and equipping teachers to learn more about ESD; contextualizing the implementation of green curricula according to local cultures; and translating the larger ESD visions from international institutions into practical classroom teaching. The broad concept of these findings can be transferred to other Green School cases while contextualizing the detailed analyses according to different cultures and geographical boundaries.

References

Auerbach, C.F. & Silverstein, L.B. (2003). Qualitative data: An introduction to coding and analysis. United States of America: New York University Press.

Bell, A.C. (2001a). Engaging spaces: on school-based habitat restoration, Canadian Journal of Environmental Education, 6, 209-224.

Bell, A.C. (2001b). The pedagogical potential of school grounds. In Grant. T. & Littlejohn. G. (Eds). Greening school grounds: Creating habitats for learning (pp. 9-11), Gabriola Island, BC, New Society.

Bell, A.C. & Dyment, J.E. (2006). Grounds for action: promoting physical activity through school ground greening in Canada (Toronto, Ont., Evergreen). Retrieved from http://www.evergreen.ca/en/lg/lg-reseources.html [4].

Boldermann, C., Blennow, M., Dal, H., Martensson, R., Raustorp, A., Yuen, K. & Wester, U. (2006). Impact of preschool environment upon children’s physical activity and sun exposure, Preventive Medicine, 42, 301-308.

Brundtland, G; Khalid, M; Agnelli, S; Al-Athel, S; Chidzero, B; Fadika, L; Hauff, V; Lang, I; Shijun, Margarita, M; Singh, M; Okita, S; and others. (1987). Our Common Future (‘Brundtland report’). Retrieved from http://www.un-documents.net/our-common-future.pdf [5]

Center for Ecoliteracy (1999). The edible schoolyard. Learning in the Real World, Berkeley, CA.

Center for Ecoliteracy. (2010). What is a Green School? Retrieved from https://www.ecoliteracy.org/sites/default/files/CEL-What-is-a-Green-School.pdf [6]

Center for Green Schools (2016). About the Center for Green Schools. Retrieved from http://www.centerforgreenschools.org/about.

Chapman, P. (2015). What is a Green School? Retrieved from http://www.nais.org/Articles/Pages/What-Is-a-Green-School.aspx

Cheskey, E. (2001). How schoolyards influence behavior. In Grant, T. & Littlejohn, G. (Eds.), Greening school grounds: creating habitats for learning (pp. 5-9). Gabriola Island, BC, New Society.

Coyle, S. (2011). Sustainable and resilient communities: A comprehensive action plan for towns, cities, and regions. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. New Jersey.

Dicicco-Bloom, B. & Crabtree, B.F. (2006). Making sense of qualitative research: The qualitative research interview. Medical Education, 40, 314-321. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02418.x/epdf [7]

Duncan, E. (2011). Report Part 2 – ESD in practice. OMEP Norway.

Dyment, J.E. (2005). Gaining ground: the power and potential of green school grounds in the Toronto District School Board (Toronto, Ont., Evergreen). Retrieved from http://www.evergreen.ca/en/lg/lg-resources.html [8].

Eco-Schools (2014). Our history. Retrieved from http://www.ecoschools.global/our- [9]history/

Engdahl, I. (2015). Early Childhood Education for Sustainability: The OMEP World Project. International Journal of Early Childhood, 47 (3), 347-366.

Engdahl, I & Rabusicova, M. (2010). Children’s Voices about the State of the Earth and Sustainable Development: A report for the OMEP World Assembly and World Congress on the OMEP World Project on Education for Sustainable Development 2009-2010.

Environmental Campaign Committee (2013). About us. Retrieved November 20, 2013. From http:www.ecc.org.hk

Fien, J. & Tilbury, D. (2002). The global challenge of sustainability. In D. Tilburry, R.B. Stevenson, J. Fien, D. Schreuder (Eds.), Education and Sustainability: Responding to the Global Challenge (pp. 1-12). IUCN Commission on Education and Communication CEC. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland, and Cambridge, UK.

Gore, A. (2009). Our choice: A plan to solve the climate crisis. New York, Rodale. Melcher Media.

Green School Initiative (2010. How do I green my school? Retrieved from http://www.greenschools.net/article.php-list=type&type=12.html

Green-Schools Ireland (2016). Green Schools in Ireland. Retrieved from http://www.greenschoolsireland.org/about-us/green-schools-in-ireland.106.html [10]

Gutter, R. (2009). New Reasons to Hope. American School Board Journal, 196(4), 46 – 48.

Harvey, M.R. (1989). Children’s experiences with vegetation, Children’s Environments Quarterly, 6(1), 36 – 43.Hopkins, C. & McKeown, R. (2002). Education for sustainable development: an internal perspective. In D. Tilbury, R. B. Stevenson, J. Fien, and D.

Schreuder, Education and Sustainability: Responding to the Global Challenge, IUCN (The World Conservation Union) Commission on Education and Communication CEC.

Hutchison, D. (1998). Growing up green: Education for ecological renewal, New York, NY, Teachers College Press.

IUCN, UNEP, WWF (1991). Caring for the Earth: A Strategy for Sustainable Living. IUCN, UNEP, WWF: Gland, Switzerland.

IUCN, UNEP, WWF (2009). Caring for the Earth: A Strategy for Sustainable Living. Earthscan, London.

Iwan, A. (2013). Negotiating the Meaning of the Green School. Hong Kong Journal of Early Childhood, 12 (2), 111-117.

Kobet, R.J. (2009). Go for the LEED: Why green represents more than just money for imaginative, innovative, school districts. American School Board Journal.

Lieberman, G.A. & Hoody, L.L. (1998). Closing the achievement gap: Using the environment as an integrated context for learning. Ponway, CA, Science Wizards. Malone, K. & Tranter, P.J. (2003a). Children’s environmental learning and the use, design and management of school grounds, Children, Youth, and Environments, 13(2).

Malone, K. & Tranter, P.J. (2003b). School grounds as sites for learning: making the most of environmental opportunities, Environmental Education Research, 9(3), 283-303.

Moore, D. (2008). It is easy to be green. Independent School, 67 (3), 76-84.Nabhan, G.P. & Trimble, S. (1994). The geography of childhood: why children need wild spaces. Boston, MA, Beacon.

National Forum on Partnership Supporting Education about the Environment (1996). Education for Sustainability: An Agenda for Action. U.S. Government Printing Office: Washington D.C.

Pancheri-Abrose, B & Tritscheler-Scali, J. (2013). Beyond Green. Young Children. Vol 68(4), 54.

Pramling-Samuelsson, Siraj-Blatchford, & Park (2013). Environment Rating Scale for Sustainable Development for the Early Childhood. Retrieved from http://www.worldomep.org/en/esd-scale-for-teachers/ [11]

Schwartz, J. (2004). Air Pollution and Children’s Health. Pediatrics, 113(4), pp. 1037-1043.

Shelter, M (2013). The Center for Green Schools at USGBC Announces 2013 Greenest School on Earth Recipients. Retrieved from http://www.centerforgreenschools.org/sites/default/files/resource-files/2013 Greenest-School-on-Earth-release.pdf [12]

Siraj-Blatchford, Smith, and Pramling Samuelsson (2016). Education for Sustainable Development in the Early Years. Retrieved from http://www.327matters.org/Docs/ESD%20Book%20Master.pdf [13]

Sobel, D. (2014). Learning to walk between the raindrops: The value of nature preschools and forest kindergartens. Children, Youth, and Environments, 24 (2), 228-238.

UNESCO (1997). Educating for a Sustainable Future: A Transdisciplinary Vision for Concerted Action. Report of the International Conference on Environment and Society: Education and Public Awareness for Sustainability, Thessalonikki: Greece.

United Nations (1992). Agenda 21, Sustainable Development Knowledge Platform. United Nations Conference on Environment and Development. Rio de Janerio, Brazil, 3 to 14 June 1992.

United Nations (2015). Sustainable Goals: 17 Goals to transform our world. Retrieved from http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable- [14]development-goals/

Titman, W. (1994) Special places, special people: the hidden curriculum of school grounds. Godalming, Surrey, World Wildlife Fund/Learning through Landscapes.

Zhang, Y.Z. (2004). Special issues on “green schools.” Thoughts on issues concerning “green schools.” Chinese Education and Society, 37 (3), 64-70.