Benefits of “Flip” Teaching Techniques in the Environmental Planning and Sustainability Classroom

Buckman JSE December 2019 General Issue PDF

Link to the JSE Fall 2019 General Issue TOC

Abstract: Breaking though to millennials in the classroom is becoming an important objective for all educators. These students demand more from their learning experiences and many traditional education techniques are often ineffective. One technique that holds potential is “Flip” education, a unique active learning approach. Although Flip is normally associated with the hard sciences, this paper presents a case study that demonstrates its effectiveness in the social sciences, specifically an upper division undergraduate environmental/sustainability planning class. Two important takeaways from this study include: 1) that teaching must be more student-centered, allowing students to take more control of their own education as assigned material be available before the fixed class time so as to allow class time for more active learning; and 2) Students report improved learning when Flip experiential methods are used in conjunction with some form of standard professor lectures.

Keywords: Flip Education, Student Centered Learning, Alternative Teaching Techniques, Sustainable Education

Introduction

Reaching millennials is becoming one of the key challenges for educators in the 21st century classroom. These students have been raised in a world of rapidly evolving technology and instant access to information. As a result, they “think and process information fundamentally differently from their predecessors” (Prensky 2001, 1). Unfortunately, the presentation of educational materials in many university classrooms has not changed significantly despite changes in outlooks and priorities. Many educators still believe in and largely practice passive teaching approaches, e.g., lectures and assessment of understanding through exams (Stewart-Wingfield and Black 2005). This traditional teaching, or teaching-centred paradigm, assumes that students are empty vessels waiting to be filled with knowledge (McManus 2001).

Traditional teaching methods including lectures certainly have a place in higher education as they allow instructors to quickly deliver new concepts to large numbers of students (Whetten and Clark 1996). While this approach has expanded through the growth of online instruction, literature shows that this form of teaching can result in lower knowledge retention after the course ends (Van Eynde and Spencer 1988) and difficulty in maintaining student attention (Dorestani 2005). Roehl, Reddy, and Shannon (2013, 45) suggest that to reach millennials, educators need to shift from primarily passive, lecture-based teaching to more engaged methods or learner-centred paradigms.

Flip education embraces learner-centred paradigms by requiring students to engage with materials prior to class then use class time to assimilate the information through problem-solving, discussion, and/or debates, among other activities. This is different than the traditional model where students are not exposed to the materials until classes begin then asked to demonstrate their understanding through homework assignments and testing (Brame 2013).

Currently, Flip education is used primarily in the hard and quantitative sciences. To see if these techniques would translate to the social sciences, specifically urban planning education, a 2017 traditional environmental sustainable planning class at a large research institution was “flipped” and active learning techniques incorporated into the curriculum. The goal was to create a blueprint that other planning classes could emulate. This paper reviews the literature around critical thinking and experiential learning as key components of active learning and learner-centred teaching paradigms, explains Flip education, then presents a case study of a flipped upper-class undergraduate planning class and the results of a post-class student survey.

Literature Review

Active learning and learner-centred paradigms incorporate technology and more stimulating, thought-provoking activities into the classroom (Roehl, Reddy, and Shannon 2013). According to Zayapragassarzan and Kumar (2012), there are four key strategies to active learning: 1) create individual activities (inside and outside of the classroom); 2) incorporate student paired activities; 3) encourage informal groups; and 3) assign cooperative student projects. Merging these ideas with a “flipped classroom” engages students more fully in the learning process. It encourages them to think more critically and provides them with opportunities to work through the information with their peers (Bonwell and Eison 1991; Michel, Cater, and Varela 2009). This has been shown to improve learning outcomes and increase overall motivation for learning (Prince 2004; Freeman et al. 2007; Lewis, Chen, and Relan 2018).

Experiential Learning

There are numerous definitions of “experiential learning.” For example, in apprenticeships, it involves on-the-job training in a trade or profession. In education, it has been defined as “a philosophy and methodology in which educators purposefully engage with students in direct experience and focused reflection in order to increase knowledge, develop skills, clarify values, and develop people’s capacity to contribute to their communities” (Association for Experiential Education, para. 2). In general, it means learning by doing and consists of a four-step cycle: 1) the experience, 2) reflection on the experience, 3) conceptualization of the experience, and 4) applying new ideas and new knowledge in a new experience (Kolb 1984).

There has been an on-going debate if experiential learning in formal education better prepares graduates for real-life jobs and if it should be incorporated into a school’s curriculum. John Dewey, an education philosopher who is often referred to as the initiator of higher education experiential learning, said “there is an intimate and necessary relation between the processes of actual experience and education” (Dewey 1984, 20). Some scholars argue that graduates without experiential training are less prepared for the workplace (Spencer and Perry 2015; Cantor 1997; Jennings and Wargnier 2010).

James March, the author of The Ambiguous (2010, 9), contrasted experiential learning with formal education by describing experiential knowledge as “lessons extracted from the ordinary course of life and work,” and academic knowledge as “generated by systematic observation and analysis by expert and transmitted by authorities” (2010, 12). March also points out the problems with experiential learning, including the impacts of inference forming and the experiences themselves (6). While it may be true that errors and erroneous beliefs may be passed down in experiential learning techniques, it is important to acknowledge that academic knowledge is not completely objective either. Educators’ personal values and biases are inadvertently or sometimes deliberately incorporated into the theories and concepts being taught. Developing students’ critical thinking skills however enables them to carefully evaluate the information they are learning, regardless of if it is through experience or in a classroom.

Critical Thinking

There has been a growing call for transformative learning in education and many have argued that the key lies in focusing on ‘how to think’ rather than focusing on ‘what to think’ (Thomas 2010; Liu et al. 2014; Beyer 2001). This has been fuelled in large part by employers’, public officials’, and educators’ increasing concern over the lack of students’ and employees’ thinking and reasoning skills, which are needed for today’s society and the increasingly technologically complex workforce (Gibson 1995; Association of American Colleges and Universities 2015). Critical thinking enables students to discern, analyse, and evaluate information to reach a logical conclusion and build upon their existing knowledge (Saadé, Morin, and Thomas 2012).

Robert Ennis, in A Logical Basis for Measuring Critical Thinking Skills (1985), defined critical thinking as “reflective and reasonable thinking that is focused on deciding what to believe or do.” As Ennis (1985) further explains, this type of thinking hinges on the ability to absorb, interpret, distil, assess and appraise, and ultimately, internalize knowledge to initiate an action or response. These skills are imperative for participating in the ever-evolving sustainability and environmental discourses (Wals & Jickling 2002) or any activity that encourages students to challenge preconceived notions and devise innovative, practical sustainable solutions. Carefully examining results and critiquing data provides students additional insights and the capacity to improve upon a model or a process (Holmes, Wieman, and Bonn 2015).

Some scholars have argued that critical thinking should not or cannot be taught in schools (Hendrick 2016; Willingham 2008). For example, Willingham, a professor of cognitive psychology at the University of Virginia, argues that critical thinking is not a skill that can be taught. Rather it is a combination of “meta-cognitive strategies” that teach us how to think about the way we think and help us put new information in context based upon our knowledge of a subject. Thus, it is domain specific and experiential (Willingham 2008). Other scholars argue that teaching students to think critically can and should be conveyed in every quality academic program—and thus serve as the foundation of academic sustainability education (Wiek, Withycombe, Redman 2011) as it is crucial for success in both their personal lives and today’s dynamic workplace.

For example, a study by Miri, David, and Uri (2007) found that when instructors “purposely and persistently” use a variety of teaching techniques and engage students in real-world problems, encourage discussion and debate, and foster curiosity and inquiry, students are more likely to develop critical thinking capabilities. Ahuna, Tinnesz, and Kiener emphasize that “because it is impossible to predict what advancements lie ahead, establishing a mindset of inquiry and effective problem solving may be the most important goal of [these] professional preparation programs” (2014, 2). These arguments also make the case for active and learner-centred paradigms that promote hands-on, experiential learning.

Flip Education

Incorporating both critical thinking and experiential learning into the flipped classroom has the potential to open new avenues of learning and teaching techniques. The idea of the flipped classroom originated in the 1990s when Harvard Physics Professor Eric Mazur (2005) looked for a new way to get material across to his students. Exactly what a flipped classroom entails has come under some debate. For instance, Roehl, Reddy, and Shannon (2013, 44) state that a flipped classroom “employs easy-to-use, readily accessible technology[i] to free class time from lecture…using class time for active learning versus lecture provides opportunities for greater teacher-to-student mentoring, peer-to-peer collaboration and cross disciplinary engagement.” Other definitions emphasize the importance of technology, especially for supplying online materials (Abeysekera and Dawson 2015; Bishop and Verleger 2013; Moore et al. 2014; Roehl, Reddy, and Shannon 2013; Strayer 2007), as a means for preparing and engaging them before coming to class (Bergmann and Sams 2012).

Despite the lack of an inclusive definition, there is agreement that class materials must expand the curriculum rather than merely re-arrange it (Bishop and Verleger 2013). Bishop and Verleger (2013) have come up with a working definition that we used in developing the flipped planning classroom presented as a case study later in this paper. First, a flipped classroom employs individual instruction and materials outside of the classroom, typically made available to students online prior to class; and second, it builds upon this instruction using interactive group learning activities inside the classroom.

With this working definition, traditional class material such as lectures and “homework” or outside of the classroom work is provided online. Students are expected to engage with these materials before coming to class and be prepared for in-class discussions and activities. This also enables students to engage with these materials throughout the course. Questions and what would traditionally be considered homework is worked through in the classroom. Thus, students use the time in class to work through problems, advance concepts, and engage in collaborative learning (Roehl, Reddy, and Shannon 2013; Tucker 2012). Through this process, students are more engaged and build a stronger background with the material (Bergman and Sams 2012; Moore et al. 2014).

Flip learning also helps students reach a higher level of learning and mental functioning. For higher levels of functioning to occur, it is important for students to understand the why and its meaning to dominate their activity rather than just engaging in passive rote learning (Stayer 2007). Per Strayer (194), for students to reach a place of stability and change, the learning environment must be structured so that they have space to reflect on their activity in this adaptation and coping process. Not only must students have space to reflect, the professor must act to help students negotiate between the personal sense they have made of the content as a result of their learning activity and the things they still need to learn before the activity is complete. Such an environment will require multiple ways for students to express their learning and multiple cycles of feedback from the professor.

It is important to understand that the instructor and student take on different roles in a flipped classroom. In a sense, the instructor becomes more of shepherd that helps lead the student rather than telling them what is right and wrong. This type of classroom not only benefits the student but also the instructor by helping them better understand what their students are learning and what pace works best (Moore 2014). Thus, the flipped classroom has the potential to realign and restructure the classroom to better engage not only millennials but all students.

While the flipped classroom does not work for all subjects, it works well “for topics where class lecture is predominately utilized to provide instruction” (Roehl, Reddy, and Shannon 2013, 46). This style of education requires a high level of maturity from the student and may best be suited for upper division undergraduate or graduate level classes (Strayer 2007) as demonstrated in this case study. The success of a flipped classroom is a combination of prepared and engaged students and instructors who apply the at-home learning to hands-on active learning in the classroom.

Because the flipped classroom can expand students’ understanding of the subject, it is especially beneficial in practitioner-driven fields such as Urban Planning and Sustainability. In these fields, the flipped classroom’s active learning components not only help students develop critical thinking skills, it allows them to practice the skills and ethics needed to transform them from students to professionals. This is a significant objective for courses in planning, particularly given that experiential learning, in the form of community-based studio workshops, is now required by the Planning Accreditation Board (PAB).

Environmental Planning: A Social Sciences Case Study

The environmental planning class chosen for this study was a senior undergraduate planning course with 42 students enrolled. Previously, this class was merged with a graduate Masters Environmental Planning course. However, the two courses were separated in response to recent PAB (Planning Accreditation Board) review recommendations.

Reading Materials: The instructor provided lectures/presentations and overviews of reading materials from the required texts—Tim Beatley’s Biophilic Cities (2010), Stephen Wheeler’s Planning for Sustainability: Creating Livable, Equitable and Ecological Communities (2013), and Zachery Smith’s The Environmental Policy Paradox (2017)—and weekly readings from reports, academic publications, and book chapters before classes began, using the university’s Blackboard system. Developing the skills to be able to succinctly and effectively communicate ideas, and debate and critically argue a point regarding these materials were key course objectives.

To practice these skills, the first assignment required each student to select four readings from the assigned materials to critique. Critiques, limited to two pages in length, had to include an evaluation of the reading, the author’s thesis and argument, the merits of the argument, and the value of the reading to the topic and/or environmental education. At the start of class when their readings were due, the students presented their critiques to the class. The information was then discussed and debated by the class.

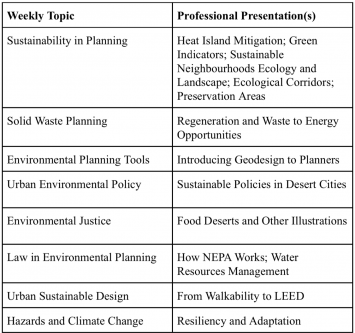

Instruction: In contrast to the traditional lecture-based course offered in years past, this course augmented these materials in class with invited speakers, largely planning practitioners. This provided students with a practitioner-planning perspective and insights into the world of planning, regulation, and policy. Because of the flipped classroom, students brought the knowledge gained from their pre-class work to bear in questioning guest speakers on where and why practices succeeded or failed in planning, alternative approaches to the topic, and related issues. In the “Class Survey on Course Effectiveness” section of this paper, survey responses show that these presentations were most useful as a learning outcome since most students intended to move onto professional planning jobs. Table 1 shows the list of weekly topics which had a corresponding presentation by a planning professional/practitioner.

Table 1: Weekly topics for which a professional/practitioner gave a presentation

It is important to mention that practitioners worked with the class instructor prior to giving their presentations to understand the students’ current level of understanding on the topic (information covered in the readings and online lectures/presentations), the nature of the topic in context of course learning objectives, and whether that topic was to be used by the students in their team research projects.

Student Team Reading Assignments: Tim Beatley’s Biophilic Cities was assigned to all students for a team exercise. Student teams of 4-6 people were tasked with developing a written and oral presentation on approaches to establishing nature in a desert city, specifically looking at the benefits of ecosystem services. They were required to review existing literature and impart personal experiences when applicable. Interviews with practitioners were also an option. At the end of the assignment, each team submitted and presented a multi–authored team project.

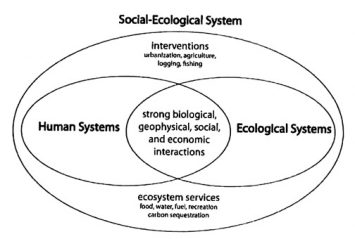

Research assignments: For two in-class assignments, students formed teams of 3-5 students to research and present applied environmental planning issues. This team-based approach, with the instructor acting as a resource when needed, provided opportunities for students to define issues related to their topic, discuss and analyse the data, reach a consensus, and organize their report. This work sought to develop and exercise students’ critical thinking, decision making, and teamwork skills, among other learning processes. Of importance to the course objectives and learning outcomes was the students’ understanding of how scholarly material and theoretical context are applied to practical and applied planning and urban science. To facilitate this, the two research assignments, a “25 Issues Analysis” and exploration of the “Socio-Environmental Nexus” in planning, asked students to consider and deliberate how to take the scholarly work on the topic and translate it into practical knowledge, and how to apply the theory for developing practical planning solutions. A brief overview of each assignment is given below.

The “25 Issues” Analysis Assignment: The assignment asked small student teams (3-4 students) to select one of twenty-five local environmental planning issues. The issues or planning problems ranged from food deserts to social justice issues in terms of access to local parks; groundwater contamination to brown cloud conditions, including problems connected to future water supplies; brownfield redevelopment; neighbourhood connectivity; among others. Students were then asked to provide a summary report and presentation for a hypothetical city council as members of a municipality’s planning staff working towards resolution of the problem.

The learning outcomes for this assignment were for 1) students to organize into a team, do research, and work together to produce a summary report; and 2) enhance clarity of communications, using both written (the report) and oral presentation skills via a 5-minute presentation with time for class questions and answers. The summary report was limited to a maximum of three pages with another page for illustrations of the final plan/design. The report had to address the following:

- The cause and/or source of the original problem and how serious the problem is to the local community. What has been or is being done to remedy the problem/issue?

- How have other cities tried to resolve the issue? Have the attempts been successful so far or not?

- How critical is it that the problem be resolved now? To what degree is the issue a local problem verses a state or federal problem? How concerned are residents and local government about this issue?

- To what degree is this problem a planning, policy, or design issue?

- What are the various alternatives to reduce the adverse impacts of the problem? Please evaluate the alternatives, argue a case for the feasibility and practicality of the alternatives, then select one alterative.

- Develop and argue for a plan, policy or a design that will support your alternative solution.

Based upon survey responses, the students thought that this exercise was an especially effective learning tool. Specific mention was made of taking the planning problem through a strategic planning model process from problem definition to alternative solutions to a final plan. Although not a requirement of the assignment, students within several teams interviewed scientists, journalists, planners/designers, and/or people in neighbourhoods under study for their perspectives and appraisal. Interviewing was an alternative method for gathering information that was new to most of the undergraduate students in this planning course. Thus, a number of students gained important skills beyond those identified as learning outcomes.

The Socio-Environmental Nexis Assignment. The last student team assignment focused on an abbreviated community-based study that connected social aspects of a neighbourhood with the environment. For example, several teams looked at how to improve the quality of life in poor neighbourhoods using needs assessments to determine the role of planning. Engagement with community members and active neighbourhood organizations has been seen to be an important learning approach in experiential learning. This assignment presented problems for students given the short turnaround time allotted for the project as well as the lack of experience for many students with studio-like courses. As a result, the final products were missing sufficient attention to the approaches and methods used. An important lesson learned was that to include mini-studio learning activities in this class required more guidance and time allotment.

Class Survey on Course Effectiveness: Does Flip Education Work in Planning Courses?

To understand the impact of the Flip teaching method, students were given an in-class survey two weeks before the end of the semester. The evaluation was done during class time and collected by the Teaching Assistant without the professor being present. Of the 42 students enrolled, 37 (88.1%) took the survey. For the analysis, 100% of the 37 students responded to a question unless indicated otherwise.

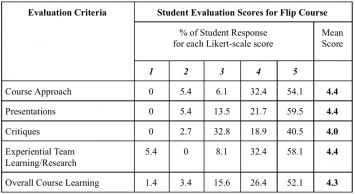

Table 2: Student Evaluation Scores

The first four questions asked students to rate the “strength” of the course on a 1- to 5-point Likert scale (described below for each criteria). These questions addressed 1) the approach, 2) invited presenters, 3) use of critiques, and 4) the team approach to community-based planning and research. Overall course learning was determined by averaging the responses to all four questions. Table 2 shows the results of the student evaluation scores for each of the learning criteria and the mean scores.Course Approach: The first question, “On a scale of 1 to 5, where 1 stands for weak a approach and 5 stands for a strong approach, how would you rate the course from 1 to 5?” More than half of the 37 students (54.1%) gave the flipped classroom approach a ‘5’ rating and another 32.4% rated the course a “4”; combined, 4 and 5 ratings totalled 86.5% of the class or 32 students. This clearly demonstrates strong support by students for the Flip teaching methodology.

Presentations: Next, students were asked, “In your opinion, on a 5-point scale where 1 is not successful and 5 is highly successful, how would you rate the incoming practitioner presentations?” The average score was 4.4 with 59% of students giving the presenters a 5.0 and only 2 students (5.4%) rating the presenters “with a low success rate.” This question received the highest ‘5’ ranking of all questions and a combined ‘4’ and ‘5’ score of 84% (successful and very successful, respectively), indicating that this was a viable approach for achieving learning outcomes.

Critiques: Using student-developed critiques was an important learning approach. The survey question pertaining to this criterion read, “You were asked to write short critiques of several readings, to present these critiques and then discuss your views in class with your classmates. Did you like this approach to learning?” The average response was 4.0 on the 1-5 Likert scale and 59.4% ranking it successful ‘4’ and very successful ‘5’. Although slightly less positive compared to the average on all other questions, critiques as a learning tool received strong overall support with 40.5% of the class ranking them a ‘5’, only one student ranking them a ‘2’, and none of the students ranking them a ‘1’.

Experiential Team Learning/Research: The last item looked at the level of perceived success of team-based experiential learning. The question asked: There were two student projects in this course. The first was on providing information on one of the 25 issues to the “Mayor of Phoenix”; the other on innovative environmental planning issues. To what degree did you think these two research projects were beneficial to your education? On a scale of 1 to 5 where 1 is “not beneficial” and 5 is “very beneficial” how would you rate the team projects in terms of learning – communication, team activities, organization of research, importance of projects, learning about your team issue? Your score 1 to 5?” As a learning tool, students found team projects highly successful and beneficial with an average score of 4.4. The combination of ‘4’ and ‘5’ represents 91.7% of the students that responded to the survey. Rankings of ‘5’ accounted for 58.1%, the second highest ranking, and 32.4% ranked team learning a ‘4’.

Overall Course Learning: Survey analysis also includes the rating all learning methods combined. The data show that very few students gave low ratings for any of the Flip education learning variables. In fact, the average rating for all four criteria as 1 and 2 totalled only 4.8%. In contrast, 78.5% of the students rated the four learning factors as 4 (26.4%) and 5 (52.1%).

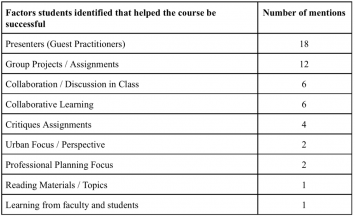

The survey also asked students to identify two aspects of the course that “you particularly liked in terms of learning.” One student did not answer the questions, resulting in a 97.3% response rate. Both guest speakers (50%) and Group Projects/Assignments (33%) received the strongest support. Table 3 provides an overview of these responses.

Table 3: Factors for success

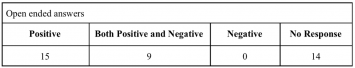

The last question was an open-ended question that asked students if they felt the overall structure for the course allowed for learning with “formal lectures from the instructor not being necessary.” The question asked: “Would you say the nature of the course – readings, critiques, class discussions and reflections, team research projects and presentations each class period resulted in learning environmental planning that did not require formal lectures from your instructor. Thoughts on this question?” Of the 37 students completing the survey, only 24 responses were returned resulting in a response rate of 64.9%. The lack of an easy YES/NO answer or Likert-scale rating may explain the lower than expected number of responses. Another explanation may be that students felt they had answered this question previously. Table 4 provides an overview of these responses.

Table 4: Impact of Limited Lectures by Instructor

The overall analysis of responses shows that 15 students felt that learning can be accomplished without formal lectures from the instructor. None of the respondents felt that limited formal lectures by the course instructor was problematic. This fact is not surprising as responses to the previous questions demonstrated that the course was successful in meeting learning objectives.

Individual responses to this specific question were quite interesting. In one case, a student voiced the opinion that formal lectures were not required to learn the topic in a comprehensive way but that “having a knowledgeable instructor on the topic is still important to facilitate the discussion.” This student noted that the instructor they had was knowledgeable.

The same student recommended that discussion questions should be given to the class while the readings are being done independently. This presents an interesting issue in ‘Flip’ instruction, as providing questions prior to the in-class discussion might constrain creativity but doing so would provide questions for students to think about as they read. This issue will be addressed in future flipped classes.

Other students stated that they liked the professional presenters coming into the class and thought the instructor should summarize the presentation(s) or provide input on the implications for planning and policy. When this approach was taken in the course, the follow-up was viewed as very beneficial. Another student suggested that he/she “enjoyed the responsibility to learn what I wanted from the course” and “there were interesting views and information from the speakers.”

Another positive voice for Flip education was that the student could learn through “interaction with class, instructor and presenters without formal lectures from the instructor.” The strongest support came through the following comment, “I thought I learned a lot more with the readings, critiques, and class discussions over a formal lecture.”

A few students indicated that they would like to see more structured lectures, not on any specific topic, but integrating all the materials. For example, one student suggested at least 2 formal lectures be given by the instructor.

Other comments noted:

- “I enjoyed the nature of the course as an unconventional learning experience. This was interactive, engaging, and offered multiple perspectives which I think is important for learning.”

- “Very simply Flip education generates ideas for solutions- engagement in learning helped in this. The interactions of the students and instructor was great therefore there was no need for formal ‘anything’ because learning from the hip is the best.”

- “Yes, formal lectures get boring… this was not a problem here by being constantly relevant to my life without flooding me with unnecessary information.”

Discussion

An important aspect of this Flip education experience was that it offered students a diversity of experiences and ideologies from outside experts. In the traditional lecture model where most or all lectures are provided by a single expert, the expert’s biases are often passed onto the students. The availability of additional experts and practitioners reduces this bias and provides a forum for faculty, practitioners, and students to have an open discussion on topics being discussed. Many assumptions that students have about the field can be challenged by practitioners who are in the thick of it. Students are also able to take advantage of the experiential learning that the practitioners have undertaken in their field and get insights to ‘short cuts’ of what works.

In addition to the diversity of instruction, class time in this Flip education experiment included literature critiques, weekly guided discussion on topics, and experiential team-based assignments and research. Critiques and discussions gave students the opportunity to formulate and defend their ideas to their peers, thereby developing useful skills for any planner. The team-based research projects encouraged students to go out into the field and get first-hand practical knowledge of an environmental planning project. These active-learning experiences expanded upon and complemented the lectures, readings, and guided discussions.

The beauty of flipped or inverted learning is that it promotes a combination of pedagogical and interactive learning methods. This has been proven to be an effective way to engage millennials and promote learning that goes beyond traditional, lecture-driven approaches (Wilson 2004; Phillips and Trainor 2014; Hotle and Garrow 2015). As demonstrated by this case study, this method is extremely beneficial for multidisciplinary planning courses such as environmental management, natural resource planning, urban planning, sustainability planning, etc. as it not only provides a theoretical background but also offers access to hands-on and real-world practical knowledge.

Flip education helps students connect the dots between the learning materials and real-life application. The interactive team-based approach makes the classroom more appealing for millennial students who welcome collaboration (Phillip and Trainor 2015, 520). Importantly, this approach introduces students to both professional expectations and prospects as well as helps them develop a professional identity (Dilullio, McGee, Kriebel 2011). Thus, this class structure presents a great opportunity for students as they transition to becoming a professional and can greatly boost students’ confidence. As students enjoy the opportunity to work with professionals, professionals also get the opportunity to interact with future professionals in their area of interest. This benefits students and professionals alike.

In addition to professional-to-student learning, the flipped classroom enabled planning students to exercise peer-to-peer learning as the class nurtured discussion and team activities. This gave students access to diverse views on planning problems and different perspectives on solving them. Thus, insightful and diversified discussion itself became a significant resource for learning as it welcomed inquiry, widened understanding, and promoted thinking out-of-the-box. It also helped students improve communication, interpersonal, and critical thinking skills. These skills are critical for student success both in school and the workforce.

The critical thinking exercises offered in the class included critiques of reading materials that honed students’ analytical skills rather than simply asking them to summarize the material. This enabled student to link theory with their understanding of the topic. Sharing their critiques with their peers not only nurtured healthy debate and discussion in the classroom but provided important insights into the critical thinking process by creating a space within which students were asked to think beyond what it is written by the author(s). This afforded self-paced and interactive learning opportunities for the students.

Group assignments offered interactive learning opportunities in applying acquired knowledge to real-world problems and solutions as well. This proved effective for helping the planning students bridge learning and practice as they gained an understanding of the importance of the theories they were learning. Group activities also bolstered teamwork, leadership, and writing skills, as students worked together to research planning issues and develop presentations to hypothetical policy makers. These skills will be invaluable in both students’ academic and professional careers.

Conclusion

The purpose of this study was to understand the effectiveness of Flip educational techniques and if they could be used in the sustainability and planning classroom. In reworking an annual environmental planning class, we moved away from the traditional lecture format (faculty-centred) to one based on active engagement and experiential learning (student-centred). In doing so, we emphasized group work, student-led critiques and discussions of the readings, and lectures by practitioners working in the fields of planning, environmentalism, and sustainability.

The findings of the post-class survey overwhelmingly showed that the Flip education techniques instituted were well received and beneficial to student learning. For example, 91.5% of the respondents thought the class was successful, rating it either a 4 or 5 on a 1- to 5-point Likert scale. When asked to rate presentations by practitioners, 59% of students gave them a 5.0 the highest ‘5’ ranking of all questions. These examples indicate that the Flip education format can be considered a success in the context of planning and that students value practitioner input and expertise as part of this experience.

While Likert-scale responses shed light on specific aspects of the class, open-ended question responses showed the most interesting results. These responses also offered the most critical insights for future attempts at Flip education for sustainability and planning courses.

There was a consensus among students that the traditional formal style of learning was not necessary to understand the material at hand. However, while Flip techniques ask for the instructor to take a step back, there was a desire for the instructor to have greater participation in two major areas—taking an active role in summarizing what was said by guest lecturers and giving at least a couple of formal lectures. Both issues can easily be rectified within the Flip structure.

First, summarizations can be conducted during the class following the practitioner lecture. This presents an opportunity for not only summarizing the previous discussion, but also for discussing how the topic(s) presented by the practitioner fit within the context of readings and online lectures. Second, formal lectures could be addressed similarly. For instance, instructor lectures need not necessarily introduce new material but could synthetize readings, online materials, guest lecturers, within the context of their own experience “from the field” and/or specific planning issues. This would allow students to have a meaningful encounter with the instructor without breaking away from the Flip structure.

While this class structure shows an example of how Flip teaching techniques can be used in the social science classroom, the structure of the class, and for that matter Flip education overall, is not a panacea to solve all issues that educators may face in connecting with millennial students. It is, however, an important technique for connecting with these and all students. Two important takeaways from this study include: 1) that teaching must be more student-centered, allowing students to take more control of their own education as assigned material be available before the fixed class time so as to allow classtime for more active learning; and 2) Students report improved learning when Flip experiential methods are used in conjunction with some form of standard professor lectures. As millennial and future generations of students demand different styles of education, it is our job as educators to meet their demands. Flip education represents one avenue that can be instilled not only in the hard sciences but also in the social sciences.

References

Abeysekera, Lakmal and Phillip Dawson. 2015. “Motivation and Cognitive Load in the Flipped Classroom: Definition, Rationale, and a Call for Research.” Higher Education Research & Development 34, no. 1: 1-14.

Ahuna, Kelly H., Christine G. Tinnesz, and Michael Kiener. 2014. “A New Era of Critical Thinking in Professional Programs.” Transformative Dialogues: Teaching & Learning Journal 7, no. 3: 1-9.

Association for Experiential Learning. What is Experiential Learning? Accessed January 11, 2019, https://www.aee.org/what-is-ee.

Association of American Colleges and Universities. (2015). Falling Short? College Learning and Career Success. Accessed January 11, 2019, https://www.aacu.org/sites/default/files/files/LEAP/2015employerstudentsurvey.pdf.

Anthony, Glenda. 1996. “Active Learning in a Constructivist Framework.” Educational Studies in Mathematics 31, no. 4: 349–69.

Beatley, Timothy. 2017. Handbook of Biophilic City Planning & Design. Washington, D.C., Island Press.

Bergmann, Jonathan and Aaron Sam. 2012. Flip Your Classroom: Reach every student in every class every day. Eugene OR: International Society for Technology in Education.

Beyer, Barry K. 2001. “What Research Says about Teaching Thinking Skills.” In Developing minds: A resource book for teaching thinking, edited by Arthur L. Costa, 275-282. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Bishop, Jacob Lowell, and Matthew A. Verleger. 2013. “The Flipped Classroom: A Survey of the Research.” In ASEE national conference proceedings, Atlanta, GA, 30, no. 9: 1-18.

Bonwell, Charles, and James A. Eison. 1991. “Active Learning: Creating Excitement in the Classroom.” 1991 ASHE-ERIC Higher Education Reports. ERIC Clearinghouse on Higher Education, The George Washington University, One Dupont Circle, Suite 630, Washington, DC 20036-1183.

Brame, Cynthia J. 2013. Flipping the Classroom. Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching. Accessed January 10, 2019 http://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guide.

Cantor, Jeffrey A. 1997. “Experiential Learning in Higher Education: Linking Classroom and Community.” ERIC Digest.

Dewey, John. 2007. Experience and education. New York: Simon and Schuster.

DiLullo, Camille, Patricia McGee, and Richard M. Kriebel. 2011. “Demystifying the Millennial student: A reassessment in measures of character and engagement in professional education.” Anatomical Sciences Education 4, no. 4: 214-226.

Dorestani, Alireza. 2005. “Is Interactive Learning Superior to Traditional Lecturing in Economics Courses?” Humanomics 21: 1–20.

Ennis, Robert H. 1985. “A logical basis for measuring critical thinking skills.” Educational leadership 43, no. 2: 44-48.

Frederickson, Norah, Phil Reed, and Viv Clifford. 2005. “Evaluating Web-Supported Learning Versus Lecture-Based Teaching: Quantitative and Qualitative Perspectives. Higher Education 50, no. 4: 645-664.

Freeman, Scott, Eileen O’Connor, John W. Parks, Matthew Cunningham, David Hurley, David Haak, Clarissa Dirks, and Mary Pat Wenderoth. 2007. “Prescribed Active Learning Increases Performance in Introductory Biology.” CBE Life Sciences Education 6, no. 2: 132–39.

Gibson, Craig. 1995. “Critical Thinking: Implications for Instruction.” American Library Association. Reference Services Division. RQ. 35, no. 1: 27-35. Accessed January 11, 2019, https://kb.osu.edu/bitstream/handle/1811/53705/4/GibsonC_RQ_1995_v35_i1_p27-35.pdf.

Hendrick, Carl. 2016. “Why schools should not teach general critical-thinking skills.” Aeon Media Group Ltd. Accessed January 11, 2019, https://aeon.co/ideas/why-schools-should-not-teach-general-critical-thinking-skills.

Holmes, N. G., Carl E. Wieman, and D. A. Bonn. 2015. “Teaching Critical Thinking.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 112, no. 36: 11199-11204: DOI:10.1073/pnas.1505329112.

Hotle, Susan L., and Laurie A. Garrow. 2015. “Effects of the Traditional and Flipped Classrooms on Undergraduate Student Opinions and Success.” Journal of Professional Issues in Engineering Education and Practice 142, no. 1. DOI: 1943-5541.0000259.

Jennings, Charles, and Jérôme Wargnier. 2010. “Experiential Learning–A Way to Develop Agile Minds in the Knowledge Economy?”. Development and Learning in Organizations: An International Journal 24, no. 3: 14-16.

Kolb, David. 1984. Experiential Learning as the Science of Learning and Development. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

Lewis, Catherine E., David C. Chen, and Anju Relan. 2018. “Implementation of a Flipped Classroom Approach to Promote Active Learning in the Third-Year Surgery Clerkship.” The American Journal of Surgery 215, no. 2: 298–303. DOI: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2017.08.050.

Liu, Ou Lydia, Lois Frankel, and Katrina Crotts Roohr. 2014. “Assessing Critical Thinking in Higher Education: Current State and Directions for Next-Generation Assessment.” ETS Research Reports Series 2014, no. 1: 1-23. DOI:10.1002/ets2.12009.

Mann, Karen V. 2011. “Theoretical Perspectives in Medical Education: Past Experience and Future Possibilities.” Medical Education 45, no. 1: 60–68.

March, James G. 2010. The Ambiguities of Experience. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN: 978-08014-4877-5

Mazur, Eric. 2005. The Essence of Physics: Version 2.0. New York: W.W. Norton.

McManus, Dean. 2001. “The Two Paradigms of Education and the Peer Review of Teaching.” Journal of Geoscience Education 49, no. 5: 423–34.

Michel, Norbert, John James Cater, and Otmar Varela. 2009. “Active versus Passive Teaching Styles: An Empirical Study of Student Learning Outcomes.” Human Resource Development Quarterly 20, no. 4: 397–418. DOI: 10.1002/hrdq.20025.

Miri, Barak, Ben-Chaim David, and Zoller Uri. 2007. “Purposely Teaching for the Promotion of Higher-order Thinking Skills: A Case of Critical Thinking.” Research in Science Education 37, no. 4: 353-369.

Moore, Amanda, Matthew R. Gillett, and Michael D. Steele. 2014. “Fostering Student Engagement with the Flip.” In Mathematics Teacher 107, no. 6: 420-425.

Phillips, Cynthia R., and Joseph E. Trainor. 2014. “Millennial Students and the Flipped Classroom.” ASBBS Proceedings 21, no. 1: 519-530.

Prensky, Marc. “Digital natives, digital immigrants part 1.” On the Horizon 9, no. 5 (2001): 1-6.

Prince, Michael. 2004. “Does Active Learning Work? A Review of the Research.” Journal of English Education 93, no. 3: 223–31.

Roehl, Amy, Shweta Linga Reddy, and Gayla Jett Shannon, 2013. “The Flipped Classroom: An Opportunity to Engage Millennial Students Through Active Learning Strategies.” Journal of Family & Consumer Sciences 105, no. 2: 44-49.

Saadé, Raafat George, Danielle Morin, and Jennifer D.E. Thomas. 2012. “Critical Thinking in E-Learning Environments.” Computers in Human Behavior 28, no. 5: 1608–17. DOI: 10.1016/j.chb.2012.03.025.

Smith, Zachery. 2012. The Environmental Policy Paradox. 7th Edition. New York: Routledge.

Spencer, Cassandra, and April Perry. 2015. “Helping students maximize their degrees as competitive tools: The value of experiential learning.” The William & Mary Educational Review 4, no. 1(5): 26-33.

Strayer, Jeremy. 2007. “The Effects of the Classroom Flip on the Learning Environment: A comparison of learning activity in a traditional classroom and a Flip classroom that used intelligent tutoring system.” PhD diss., The Ohio State University. OhioLINK ETD (osu1189523914).

Thomas, Ian. 2010. “Critical Thinking, Transformative Learning, Sustainable Education, and Problem-Based Learning in Universities.” Journal of Transformative Education 7, no. 3: 245-264. DOI: 10.1177%2F1541344610385753.

Tucker, Bill. 2012. “The Flipped Classroom” Education Next 12, no. 1: 82-83.

Van Eynde, Donald F., and Roger W. Spencer. 1988. “Lecture Versus Experiential Learning: Their Different Effects on Long-Term Memory.” Organizational Behavior Teaching Review 12, no. 4: 52–58.

Wals Arjen E. J., Bob Jickling. 2002. ““Sustainability” in higher education: from doublethink and newspeak to critical thinking and meaningful learning.” Higher Education Policy 15, no. 2: 121-131. DOI: 10.1016/S0952-8733(02)00003.

Wheeler, Stephen M. 2013. Planning for Sustainability: Creating Livable, Equitable and Ecological Communities. Abingdon, UK; New York: Routledge.

Whetten, David A., and Sue Campbell Clark. 1996. “An Integrated Model for Teaching Management Skills.” Journal of Management Education 20, no. 2: 152–181.

Wiek, Arnim, Lauren Withycombe, and Charles L. Redman. 2011. “Key Competencies in Sustainability: A Reference Framework for Academic Program Development.” Sustainability Science 6, no. 2: 203-218.

Willingham, Daniel T. 2008. “Critical thinking: Why is it so hard to teach?”. Arts Education Policy Review 109, no. 4: 21-32.

Wilson, Maureen E. 2004. “Teaching, learning, and millennial students.” New directions for student services 2004, no. 106: 59-71. Doi.org/10.1002/ss.125.

Wingfield, Sue Stewart, and Gregory S. Black. 2005. “Active versus Passive Course Designs: The Impact on Student Outcomes.” Journal of Education for Business 81, no. 2: 119–25.

Zayapragassarzan, Z. and Santosh Kumar, 2012. “Active Learning Methods.” NTTC Bulletin 19, no. 1: 3-5. Accessed January 10, 2019, https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED538497.pdf.

[i] The Flip classroom relies on at home technology (lectures, videos, slides, etc) to allow students to be fully prepared for the interactive activities that take place in the classroom.

Stephen Buckman, PhD: Assistant Professor of City Planning and Real Estate Development at Clemson University. Research interests include: Community Resiliency, Economic Development, Real Estate Development, and Waterfront Development

Stephen Buckman, PhD: Assistant Professor of City Planning and Real Estate Development at Clemson University. Research interests include: Community Resiliency, Economic Development, Real Estate Development, and Waterfront Development  David Pijawka is Professor, School of Geographical Sciences and Urban Planning at Arizona State University and was the Director of the PhD program of the School of Architecture, Design and Planning. He is also a Senior Scientist in the Global Institute of Sustainability He authored books on nuclear energy, recovery after disasters, community developed, and urban sustainability among others and is known for co-editing an undergraduate textbook titled Sustainability for the 21st Century. He has received numerous awards including an NAACP Award for his work on justice and equity and recently awards for his work on Geodesign and land use planning for American Indian communities.

David Pijawka is Professor, School of Geographical Sciences and Urban Planning at Arizona State University and was the Director of the PhD program of the School of Architecture, Design and Planning. He is also a Senior Scientist in the Global Institute of Sustainability He authored books on nuclear energy, recovery after disasters, community developed, and urban sustainability among others and is known for co-editing an undergraduate textbook titled Sustainability for the 21st Century. He has received numerous awards including an NAACP Award for his work on justice and equity and recently awards for his work on Geodesign and land use planning for American Indian communities.  Matthew Gomez is a graduate of Arizona State University Masters in Urban and Environmental Planning program and is a transportation and community development planner in Phoenix AZ working for an international consulting firm.

Matthew Gomez is a graduate of Arizona State University Masters in Urban and Environmental Planning program and is a transportation and community development planner in Phoenix AZ working for an international consulting firm.  Jonathan Davis, PhD: Arizona State University's School of Geographical Sciences and Urban Planning. Research Interests: Geodesign, American Indian Community Planning, Public participation, Spatial Analysis, GIScience, Resiliency & Sustainability, Ecosystem Services, Disaster Recovery, Historical GIS, Evaluation Methodologies

Jonathan Davis, PhD: Arizona State University's School of Geographical Sciences and Urban Planning. Research Interests: Geodesign, American Indian Community Planning, Public participation, Spatial Analysis, GIScience, Resiliency & Sustainability, Ecosystem Services, Disaster Recovery, Historical GIS, Evaluation Methodologies  Adenike K. Opejin: PhD Student, School of Sustainability Arizona State University

Research Interest: environmental planning, resource management, food systems sustainability

Adenike K. Opejin: PhD Student, School of Sustainability Arizona State University

Research Interest: environmental planning, resource management, food systems sustainability  Yousuf Mahid: Master of Urban and Environmental Planning School of Geographical Science and Urban Planning, Arizona State University

Yousuf Mahid: Master of Urban and Environmental Planning School of Geographical Science and Urban Planning, Arizona State University