CASE STUDY

There is much discussion in sustainability education about the urgent need for a wholesale paradigm shift and much debate about the role of incremental, grassroots change in societal transformation. Eason and Heroux describe a creative and pragmatic project that addresses behavior change through an incremental approach. Their case study provides a provocative example of how a grassroots effort to change energy consumption can have growing implications for campuses’ climate impact through the viral nature of student culture. Their “Green’s List” is a fine and replicable model for the role of celebration in community transformation.

INTRODUCTION

“Beyond simply adding a few classes on environmental issues and sustainability, a growing cadre of individuals and organizations concerned about the fate of our ecological and social structures are calling for a fundamental rethinking of how institutions of higher education educate students, conduct research, interact with local communities and ecosystems, operate campuses, and provide a model for other institutions. Institutions of higher education clearly have the ability to be leaders in sustainable thought and practice” (Shriberg, 2004). But how does a university go about this? From global climate change to rising energy prices and the search for alternative energies, environmental education must be clearly modeled for students in order for them to incorporate and apply what they have learned as they move beyond their university experience and into their chosen careers and lives. How is environmental education made relevant for our students? Dr. David Orr said it best: “All education is environmental education. By what is included or excluded we teach students that they are part of or apart from the natural world. To teach economics, for example, without reference to the laws of thermodynamics or those of ecology is to teach a fundamentally important ecological lesson: that physics and ecology have nothing to do with the economy. That just happens to be dead wrong. The same is true throughout all of the curriculum[1] [2] ” (Orr, 1996, p.12). The challenge, of course, is to motivate and inspire students to realize that even though we face tremendous challenges, actually doing something about the issues mentioned above is possible even if it is on a smaller scale.

The University of Maine Farmington’s (UMF) Sustainable Campus Coalition (SCC) is an organization comprised of students, faculty and staff that facilitates environmental activism and student civic engagement [UMF SCC,http [3]:// [3]sustainablecampus [3]. [3]umf [3]. [3]maine [3]. [3]edu [3] ]. The organization was created as part of the university’s commitment to building a sustainable future and was highly supported by the administration. When UMF president Theo Kalikow signed the American Colleges and Universities Presidents’ Climate Commitment in 2007, our pledge to achieve carbon neutrality was consistent with long-held values at the college and with our mission, which commits us to educate students to be environmental stewards. In addition, our Environmental Sustainability Vision Statement (see below) had already set us on a path towards educating the campus and community and modeling best practices in our own use of energy and resources.

UMF’s Green Vision Statement: “Sustainable practices will be an integral part of our campus management and operations, in building and renovating, in reducing pollution and waste, in using appropriate energy resources and materials, and in protecting and incorporating the native environment in our campus spaces. Indoor and outdoor environments should be healthful and aesthetically pleasing. Committing to environmental responsibility means that we will also set goals for ourselves and monitor our progress towards them.

The mission of the SCC has broadened considerably since it began in 2002 to include public education, collaborations with community organizations, municipalities and schools, assessment and mitigation planning associated with greenhouse gas emissions, improvement of recycling on campus, development of a campus organic garden and orchard, encouragement of local food and institutional composting, and reduction of automobile idling. This article will describe an SCC project involving the creation and implementation of the UMF’s Green’s List; a certification program that motivates everyone on campus to work towards more sustainable habits.

DEVELOPMENT

The idea to create the Green’s List came about while developing UMF’s Green Vision Statement. UMF has three United States Green Building Council (USGBC) Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) certified buildings and is committed to all new construction being LEED certified [USGBC LEED Program,http [4]:// [4]www [4]. [4]usgbc [4]. [4]org [4]/ [4]DisplayPage [4]. [4]aspx [4]? [4]CategoryID [4]=19 [4]]. However, like most universities, UMF has many old buildings and the idea at the foundation of this project was determining how to make these old buildings more sustainable. In addition to certification for new construction, the USGBC also has a LEED certification program for existing buildings. [USGBC LEED Certification for Existing Buildings,http [5]:// [5]www [5]. [5]usgbc [5]. [5]org [5]/ [5]DisplayPage [5]. [5]aspx [5]? [5]CMSPageID [5]=221 [5] ]. The thought of having our oldest residence hall become LEED certified was the beginning of the Green’s List development.

The first steps involved talking to our facilities management director and looking inside our residence halls. Facilities staff mentioned that there were few things that could be done to improve the function of the buildings beyond what was already accomplished. New energy efficient lighting and windows had already been installed in the buildings and the only way to achieve any other significant improvements was to replace the hot water or heating systems, which would be prohibitively expensive. Trying to obtain LEED certification, while useful for publicity, was not deemed to be worth the costs. Upon visiting the residence halls it was clear that there wasn’t much outside of the students’ rooms that could be changed. The greatest source of energy use, and therefore the greatest place to make an impact, was inside the individual rooms. The plan was then to come up with our own certification process, modeling it after the USGBC’s LEED ranking (platinum, gold, and silver) to encourage sustainable habits by the students living in the residence halls.

The certification idea was presented to the SCC in hopes of getting students involved, since they are the ones living in the residence halls and could facilitate the greatest change. Additionally, Grace Eason offered the proposal as an opportunity for students in her Introductory Environmental Science class who are required to do a class project, including a service learning option. Two students from her class adopted the project and were charged with the task of looking around their rooms and determining where energy was being used. Some examples included, coffee makers, refrigerators, gaming systems, and lighting. The next step was to group those items and develop a scoring system based on best practices.

At the end of the semester the students developed a Green Certified Checklist based on 10 categories with variable points per category. They tried their simple checklist in several rooms and presented their results to their class. The following semester two paid student workers from the SCC began work on the project. The students were motivated to participate because they felt the project would eventually become something in which they could take great pride, and they realized the potential that it had for improving UMF.

The first accomplishment of the students was to change the name from Green Dorm Certification to “Green’s List” (modified from Dean’s List) which was catchy and something that would be easily remembered by students. The theme was to recognize someone’s rating on a sustainability level rather than an academic level. We met with these students and worked out our next plan. One issue that needed to be solved was having a simple rubric to distinguish between rooms that had good practices and those that needed work. Also, the process needed to be simple for the SCC students conducting the certification and to have clear steps for students in the residence halls to improve their scores. As the SCC students began going door-to-door, they learned more and more about how to better certify rooms and how to make their efforts more efficient. Eventually, the students just kept scores on small slips of paper and gave a copy to the residents.

As the certification process continued the Green’s List was revised based on student experiences in the residence halls. It was not our goal to discourage the use of any item or reward students who abandoned technology. For example, in the original version students could only earn full points if they did not have a gaming system. Our goal was not to teach that the only way to be as green as possible was to avoid technology. In order to reflect our aim to promote best practices, the rubric was changed to award full points for “All systems plugged into a power strip and power strip is shut off when not in use, or all systems unplugged. Another example of changes made during development was to the heating category. Students have little control over the heating of their rooms as the systems are very old and hard to control. Some parts of the residence halls overheat, leading students to open their windows when the heat is on. It was decided that a more sustainable choice in such cases was to contact facilities management to make them aware of the temperature and investigate what could be done to mitigate the situation. The heating section of the checklist was changed to allow students to still earn a point for “Leaves windows open for a long period of time while the heat is on but notifies Facilities.” While it was still a bad habit to open the window, the checklist could be used as a teaching tool so that students would feel that progress was being made toward more sustainable habits.

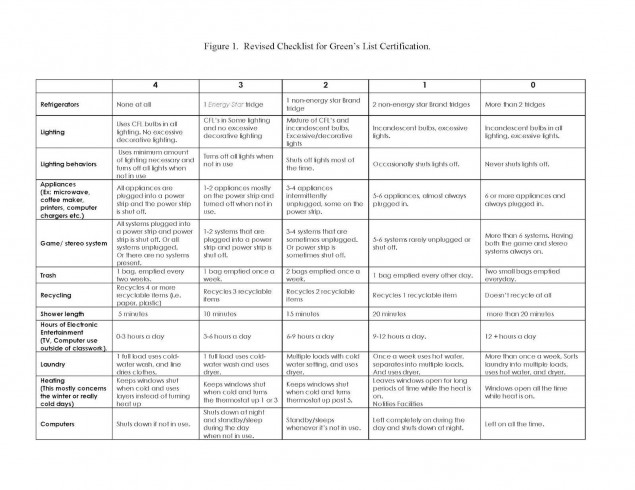

The final change was to divide some categories, such as lighting, in order to separate technology from habits, making the list slightly longer in order to increase the number of total points and provide for greater separation between the certified groups The Checklist (Figure 1) has a maximum score of 48 points. Students obtain Green status, the highest rating, by earning a minimum of 42 points. Gold and Silver are achieved by earning 36-41 and 30-35 points, respectively. Bronze certification was awarded to students below this level.

Implementation/challenges

The first challenge was actually getting into the residence halls. There is a “no soliciting” policy at UMF, which prevented the SCC students from going door-to-door. To address this challenge, they posted sign-up sheets in the residence halls for students wishing to have their rooms certified. This proved to be unsuccessful[2] [6] ; they had very few students actually volunteer their rooms. Permission was needed from the administration to grant an exception to the solicitation policy so that students could be surveyed in their rooms. The second challenge was getting students to listen and to be positive about the process (many were afraid to be judged). The SCC students worked very hard on clearly stating the purpose of their visit and made it a fun experience. They started to create door decorations to acknowledge certification levels for the rooms and students in the residence halls started to become competitive with each other regarding “who is greener?” A third challenge was collecting scores accurately and keeping track of them. Initially scores were on paper and then an online scoring instrument was used. Early on it was typical that students performing the certification [3] [7] saved only the final score. LimeSurvey version 1.82 was used to generate a computer[4] [8] -based checklist that could be used by students as they certified each room. The data for each question were stored on the university computer network. In addition to the questions in the checklist, the computer based survey gathered residence hall, room number and person conducting the survey for metadata. Lastly, it was also difficult to get a significant number of rooms completed with only two SCC students being involved in this project, so increasing the number of volunteers was the key for success. Our initial process involved attempting to score every residence hall twice during the fall semester. This goal was difficult to achieve due to time constraints and the lack of student volunteers. We addressed this challenge by first determining how many students would be able to fully commit to this project and then we scaled back the number of residence halls that needed to be certified. This enabled SCC students to visit the same residence halls twice in a semester. During the fall semester we had four student volunteers who certified two residence halls. Currently we have two experienced students training new students to use the online instrument and to minimize the subjectivity of interpreting the checklist. Our intent is to continually have experienced students train new students, typically underclassmen, who will be capable of sustaining the program.

Preliminary Data:

Data were gathered from over 100 rooms in the fall of 2010 using a prototype of the checklist (11 categories, 44 points possible). The rooms were recertified near the end of the semester using the same checklist. Table 1 shows the results for two residence halls using the prototype checklist. In both cases there was an improvement in the overall score. Over two thirds of the rooms showed improvement, while 16 percent of the rooms showed no change and 16 percent showed a decrease in their scores.

Table 1. Green’s List results for Fall Semester based on the original checklist. First score indicates the initial ranking determined at the middle of the semester. The 2nd score indicates averages based on the same rooms being rechecked later in the semester.

|

Residence Hall

|

1st Score average |

2nd Score average |

% of rooms with improved scores |

|

Scott West n=11 |

31.7 |

33.7 |

82 |

|

Scott North n=37 |

30.6 |

32.1 |

67a |

| a The number of rooms that showed no change was equal to the number of rooms that showed a decrease in their score. |

Table 2 shows results for individual scores from the computer[5] [9] -based survey (12 categories, 48 maximum points). The increases seen in the previous work were repeated in these results. In all cases overall improvement of 5-6 percent was seen from the initial certification. Analysis of data for individual categories shows large improvement in some areas. Both the Game/Stereo and Trash categories improved by 14%. The practice of using of surge protectors to reduce standby consumption was strongly advocated by the students during the initial certification and some rooms were given free surge protectors at that time. The improvement in the Trash category can be attributed to a collaborative effort between the SCC and facilities management to restrengthen recycling efforts in the residence halls. While the Lighting category only showed a 5% increase from earlier certification, all rooms were certified to “uses minimum amount of lighting necessary and turns off all lights when not in use” earning the highest score possible for that category.

Both Laundry and Heating showed an overall decrease in scores. As mentioned earlier, students have little to no control of the heat and the scores can be influenced by outdoor temperatures. On warm days the heat frequently remains on resulting in more students opening their windows to find relief from the heat. Since the second certification was taken later in the spring semester, there was a greater likelihood that a room would earn a lower score.

As expected the Light Hardware, Appliances, and Refrigerator categories showed little improvement. These three categories are least linked to student habits that can be easily changed; i.e., there was little chance for them to change appliances in their rooms during the semester. However, these data are being used to help inform residence hall policies and practices for incoming students. Policies that limit to one the number of refrigerators allowed and advising incoming students to purchase energy star rated appliances are examples of two initiatives at UMF resulting in part from this work.

Table 2. Results of modified Green’s List for Purrington Hall, University of Maine at Farmington. Average scores for individual categories are shown from initial and subsequent certification. (A higher overall score was possible compared to previous versions)

|

CATEGORYa |

1st Score |

2nd Score |

| Refrigerators |

2.3 |

2.4 |

| Light hardware |

3.1 |

3.2 |

| Light behavior |

3.8 |

4.0 |

| Appliances |

2.5 |

2.5 |

| Game/stereo |

2.8 |

3.2 |

| Trash |

2.8 |

3.2 |

| Recycling |

3.0 |

3.2 |

| Shower |

2.3 |

2.5 |

| Entertainment |

2.6 |

2.9 |

| Laundry |

3.4 |

3.3 |

| Heating |

2.7 |

2.6 |

| Computers |

3.0 |

3.0 |

| Average Total |

34.3 |

36.2 |

a See Figure 1 for category detail

Future Directions

The SCC continues to implement the Green’s List and interpret the data to improve the tool. Increasing the visibility of the project is a continuing endeavor. Having more visible signage for each room and promoting the students who excel at sustainable habits to the wider campus audience are key efforts. Another key future direction is promoting the adoption of the Green’s List at other institutions. The two SCC students most involved in the project provided five suggestions for implementation at other institutions.

1. Have your student workers/volunteers get to know your campus and tailor the checklist for your own institution. Use the checklist as a starting point and determine how each category relates to your students on-campus lifestyle habits.

2. Develop a training program that includes enough students to allow the program to succeed. Students should certify a few rooms as a test run during the student training process and agree upon objective standards.

3. Keep things simple; for example, start with one residence hall and attempt to add more as student workers/volunteers increase.

4. Have your student workers/volunteers connect with the students living in the residence halls and offer practical advice to those students that are looking to live a more sustainable lifestyle.

5. Be sure your student workers/volunteers know what resources are available in your area and the inexpensive, simple ways that students can live a more environmentally friendly lifestyle even in college and beyond.

Conclusions

Despite numerous challenges, we feel that this project has been very successful on multiple levels. First, students who worked on the project became deeply involved in how the campus operates, and they felt that they were truly contributing to the campus community. Second, as faculty members who have been supervising our SCC students, we were impressed with their level of commitment and we learned a tremendous amount regarding what it takes to keep our students motivated and focused on the project goals. Third, data gathered from the checklist have allowed us to make informed decisions about residence hall policy and provide a platform to discuss sustainable habits with the students. Lastly, as we continue to refine this project we look forward to further integrating our sustainability efforts into the UMF curricular framework through a variety of campus civic engagement initiatives.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank the UMF Sustainable Campus Coalition and the following SCC students who worked very hard on this project; Hannah Abbott, Zellie Werner, Rachel Fritschy, and Jourdan Merritt.

References

[1] Shriberg, M. (2004). Sustainability in U.S. Higher Education: Organizational factors influencing campus environmental performance and leadership. Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI.

[2] Orr, D. (1996). What is education for? Six myths about the foundations of modern education, and six new principles to replace them. The Learning Revolution, (27), 52.

[3] Sustainable Campus Coalition, “The SCC.” Sustainable Campus Coalition, 2009.http [3]:// [3]sustainablecampus [3]. [3]umf [3]. [3]maine [3]. [3]edu [3]/ [3]

[4] U.S. Green Building Council, (USGBC), http://www.usgbc.org[6] [10] /