Link to the JSE December 2020 General Issue Table of Contents

Hurley JSE December 2020 General Issue PDF [2]

Abstract: This paper describes the outcomes of a game designed to teach advanced leadership skills, specifically influence and negotiation strategies, to current and aspiring sustainability professionals at Virginia Tech’s Center for Leadership in Global Sustainability. In the game, students assume the role of a key stakeholder and practice principle-based negotiation, conflict management, consensus building, and related influence skills needed by professionals working on complex sustainable development challenges such as the transboundary resource issues regarding hydropower and watershed management. We collected pre- and post- survey data to assess the effectiveness of the simulation in developing students’ negotiation and influence skills. Results suggest that the training helps students develop confidence in using influence and negotiation skills and feel more competent and better prepared to serve as leaders in the field.

Keywords: sustainable development, transboundary resources, negotiation, problem-based learning, role-playing, pedagogy, higher education

The Power Game: Developing Influence and Negotiation Skills for Sustainable Development

The Context: Sustainable Development & Transboundary Resource Management

Water, water, everywhere and not a drop to drink. Earth’s surface is nearly 75% covered in water, yet less than 1% of that water is readily available for human use and about 1.2 billion people, nearly 20% of the world’s population, currently live in water scarce regions. This latter number could climb to 3.5 billion by 2025, making Samuel Taylor’s classic quip an omnipresent reality (EPA, 2018; World Resources Institute, n.d.). In 2018 in South Africa, population growth and prolonged drought drove reservoirs down to 26% of their capacity (Voiland, 2018). Water rationing ensued and “Day Zero” marked the day when the proverbial well would run dry and Cape Town would turn off the water supply to 4 million people, threatening not only human health and well-being but also an economy dependent on tourism and agriculture (Welch, 2018). The Colorado River Research Group (2020) notes that in the Colorado River Basin, which includes seven states and provides water to nearly 30 million people and irrigation for nearly 4 million acres of land (Evenson, et al., 2018), is in a period of “megadrought” and that aridification, increased drying, is expected. In many of the 97 drainage basins in the Northern Hemisphere where the water supply of 2 billion people depends on annual snowmelt, the snowpack is shrinking (Mankin et al., 2015). Fresh water aquifers in coastal communities around the world, from California to India, are becoming unusable as a result of saltwater intrusion. While climate change plays a significant role in many of these problems, they are also magnified by an expanding global middle class population that is demanding more water for agriculture, energy production, and personal use (Kharas, 2017). Inadequate or aging infrastructure, pollution, and political dynamics further strain our water resources.

This issue of water scarcity is a significant challenge for sustainability professionals to address. The challenge is further complicated by the fact that most of our water resources are transboundary, meaning that they cross state, national, or international borders. The United Nations notes that nearly 90% of the global population lives in the 153 countries that share transboundary water (UN High Level Panel on Water, n.d.; UN-Water, 2018). Furthermore, transboundary lake and river basins account for 60% of global freshwater (UN-Water, 2008). Therefore, it is of no surprise that many of the more than 1,400 dams or water diversion projects underway or planned are on rivers that flow through multiple nations (Oregon State University, 2017). As water resources become increasingly scarce, the competition for water could result in upstream winners and downstream losers in the game of water security, setting the stage for conflict. For example, precipitation is expected to decrease in Turkey and Syria by about 16%, reducing flows on the Euphrates and Tigris rivers. Turkey and Syria will likely increase their water storage capacity in response, further limiting the flows downstream into Iraq where water shortages are already estimated to have led to the displacement of 15,000 people as of January 2019 (Guiu, 2020).

Conflict over water resources is not new, however. States and nations have fought over water and used water as a weapon for thousands of years (Wray-McCann, 2018). Nevertheless, rather than fuel for conflict, the universal human need for water can serve as a catalyst for cooperation that supports international trade, economic development, navigation, energy generation, ecosystem protection, and broader regional integration (UNDESA, 2014; U.N-Water, n.d.; UN-Water, 2018). Cooperation regarding the development and management of transboundary water resources is so critical to overall sustainable development and peace that it is explicitly addressed by the UN Sustainable Development Goal 6.5 which states: By 2030, implement integrated water resources management at all levels, including through transboundary cooperation as appropriate.

Increasing water scarcity, and the potential for conflict, underscores the importance of cooperative management and development of our water resources. Although an estimated 450 transboundary water treaties have been adopted since 1820, many existing treaties and institutions are weak in terms of mandate, design, resources, and enforcement mechanisms. The UN further estimates that approximately 60% of transboundary river basins worldwide lack cooperative arrangements altogether, including the Euphrates-Tigris river system (Guiu, 2020; UN High Level Panel on Water, n.d.). Despite the benefits associated with cooperative arrangements, as noted above, the collaboration necessary to develop them is not easy to achieve. Stakeholders with disparate values, goals, and needs and who represent citizens, private and public sector organizations from different states and countries must develop the trust and relationships necessary to forge mutually beneficial solutions and agreements, not an easy task to be sure. A primary goal of the Virginia Tech Master of Natural Resources program is to help our students develop the competencies and strategies vital for collaborative decision-making regarding the management of water resources and, more broadly, sustainable development.

Key Competencies for Sustainability Professionals: Knowledge, Skills, and Attitudes

Leadership skills, including influence and negotiation strategies, group decision-making, conflict management, and consensus building are among the recognized core competencies for sustainability professionals and are particularly relevant to collaborative efforts to manage transboundary resources (Perlstein et al., 2017; UNESCO, 2017; Wiek et al., 2011; Hull et al. 2020). These competencies are difficult to teach and are best developed and acquired through experience and reflection (UNESCO, 2017). Pedagogical approaches that support self-directed learning, participation and collaboration, problem orientation, inter- and transdisciplinarity, and the linking of formal and informal learning, create opportunities for students to develop the relevant competencies (UNESCO, 2017; Hull et al. 2018; Hull et al. 2019). Appropriate strategies include role-plays and simulations, problem-based learning, and reflection (Cotton & Winter, 2010; Lozano et al., 2017).

The Master of Natural Resources degree at Virginia Tech designs opportunities for students to not only further their knowledge through practice but to also explore other aspects of their development such as social and emotional skills, which are also vital to collaborative problem solving (Brundiers et al., 2010; Dobson & Tomkinson, 2012; Wiek et al., 2014). Brundiers et al. (2010) argue that students must be exposed to real-world problems so that they can develop the ability to be creative and successful problem solvers. Therefore, we seek to expose students to the challenges of solving the transdisciplinary, multi-stakeholder problems they are likely to encounter as sustainability professionals. Simulation games are suitable for this task because they simulate realistic situations that require the integration of intellect, knowledge, emotions, and social skills (Hofstede et al., 2010).

We designed three games that are fictionalized scenarios designed to simulate complex transboundary water management challenges that a sustainability professional may confront (Dobson & Tomkinson, 2012). Each explores hydropower dam development; one along the Mekong River in Southeast Asia, one on the River Sava in Central and Southeastern Europe, and one on the Nile River in Africa. In these simulation games, students assume the role of a stakeholder and use learned negotiation and influence strategies to solve these real-world challenges (Perlstein, et al., 2017). By utilizing a problem-based learning format, we encourage students to construct and apply their own knowledge and engage in the conceptual and practical aspects of natural resource management challenges (Cotton & Winter, 2010; Hmelo-Silver, 2004). The role-playing aspect enables students to take a deep dive into the perspective of another stakeholder, thus broadening their own perspectives and cultivating empathy. Our goal is to provide our students with the knowledge and confidence to engage in situations where they can facilitate negotiations and influence outcomes that alleviate conflict over resources and lead to a more sustainable future

Preparation for Game Play

In the months leading up to the simulation students study principles of negotiation and influence. Students learn how to recognize the underlying interests, both theirs and those of their counterparts, that are at the heart of every negotiation. They also consider the role that fairness, relationships, and communication play in our ability to negotiate an agreement. Students also learn to identify and leverage various agreement options, including best alternatives to a negotiated agreement (BATNA). Finally, students also review different strategies for engaging in negotiations such as positional bargaining and they spend time reflecting on what makes interest-based negotiation easy and what could make it difficult.

The ability to influence the ideas, opinions, and actions of others in a negotiation may be pivotal to actually reaching an agreement, especially with regard to sustainability challenges where no one person has authority. However, to be effective at influencing others, we must first understand our own interpersonal behaviors on which we naturally rely. To learn about their own influence style, students complete the Influence Style IndicatorTM (ISI) assessment. The ISI reveals an individual’s preferred, secondary, and underutilized influence style. The ISI model identifies five influence styles: rationalizing, asserting, negotiating, inspiring, and bridging. The different styles are best suited for different situations as they each emphasize different strategies that range from a reliance on position and power to education, encouragement, and collaboration (Discovery Learning, 2013). Once students understand their personal styles of influence, they can learn when to utilize a different style of influence and how to recognize and respond to the influence styles of others.

In each game, students assume the role of an affected stakeholder and attend a meeting to discuss the challenges and opportunities stemming from the proposed hydropower dam project, which is all based on actual events unfolding in the Mekong, Sava, or Nile river basins. Their main objective is to reach consensus regarding project implementation, ensuring that all involved parties reach a mutually acceptable solution, balancing the needs of all stakeholders. To effectively play their part, students are provided with reports and readings that support their assigned stakeholder’s perspective so that they understand their interests and can formulate their BATNA. They further prepare by researching the role and importance of the riverine system and applying their systems thinking skills to understanding the current problems threatening the integrity of the system. They are also asked to reflect on how power dynamics, competing objectives, science or “facts”, and politics are likely to complicate negotiations. Post-simulation, in keeping with the problem-based format, students write a press release, from the perspective of their stakeholder, summarizing the negotiation process and outcome while advancing their organization’s agenda.

By playing the simulation game and preparing a press-release, students have the opportunity to test their developing competencies and practice their negotiation and influence skills. Students get to experience and internalize the nuances of communication in a high-stakes scenario. Assuming the role of a stakeholder helps students develop their empathy as well as recognize their own personal assumptions, thought processes, biases, and values as they contrast them with those of their character. The games are a fun, low-pressure way to safely experiment with different styles of communication, influence, and negotiation (Dieleman & Huisingh, 2006). They also allow students to experience working with others to find solutions that might be agreeable to all parties. The games are a microcosm of the strategies, structures, cultures, roles, and conflict that they may confront in their professional lives (Hofstede et al., 2010). Thus, students begin to recognize and employ the creativity, innovation, communication, and leadership needed to solve complex sustainable development problems.

Methods

The game has been played with approximately thirty participants on three occasions between 2017-2019. On each occasion, the participants have consisted of approximately thirty graduate students ranging in age from mid-20s to mid-60s with professional work experience and backgrounds spanning the private and public sectors. Participants completed a six-question survey in which they assess their confidence employing competencies in negotiation and influence. The survey is administered anonymously, online, both pre- and post-simulation.

Results and Discussion

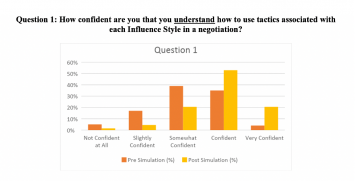

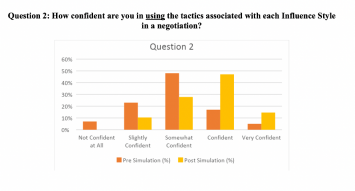

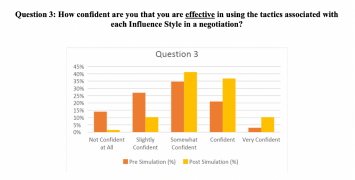

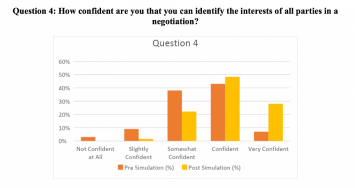

A total of one hundred students completed the pre-simulation survey and sixty-eight completed the post-simulation survey. Survey questions and results are presented in Table 1.

Considering the first two questions, which concern knowing how to use and applying influence styles, we see a general shift of approximately 18% of students moving from the Not Confident and Slightly Confident levels to the higher levels of confidence. The greatest gain in both instances was in the number of students who felt Confident or Very Confident in their knowledge of and ability to use influence strategies following the simulation, which was 35% for Question 1 and 40% for Question 2. In other words, confidence levels increased as a result of the training.

Students also report that they feel more confident about their ability to use influence tactics effectively after playing the game, as reflected in their responses to Question 3. Twenty-three percent of students moved from the Not Confident or Slightly Confident levels to the higher confidence levels. Post-simulation, the percentage of students reporting they are at least Somewhat Confident using influence strategies effectively was 88%, a 30% increase.

Questions 1, 2, and 3 are each about knowledge and use of influence strategies and the data align with Bloom’s Taxonomy of the cognitive and affective learning domains. Knowing how to use influence strategies involves recall of facts and knowledge and perhaps being able to explain or recognize the strategies, a basic learning goal. However, being able to apply the strategies in a given situation is more complex because the student must be able to put their knowledge and understanding to work. Using the strategies effectively demands that the student be able to analyze the situation, evaluate which influence strategies will be most valuable, and then leverage the most advantageous ones, even those that they are not predisposed to using. Because this is the most complex and abstract demonstration of their learning, it is not surprising that students express relatively less confidence in this ability.

Pre-simulation, students report a generally high level of confidence in their ability to identify the interests of all parties in a negotiation, with 88% reporting that they were at least Somewhat Confident. The number of students that indicated they felt Confident or Very Confident post-simulation increased 26%.

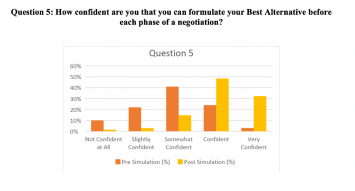

Overall, students were reasonably confident that they could identify their BATNA prior to the simulation, with 68% reporting that they were at least somewhat confident in their ability to do so. The number of students reporting they felt Confident or Very Confident they could formulate their BATNA post-simulation was 81%, a 54% increase. This gain was the largest reported in the survey.

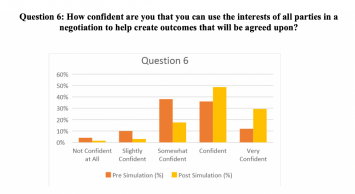

Most students reported they were at least somewhat confident that they could use the interests of all parties in a negotiation to generate agreements, with 86% percent of students reporting that they were Somewhat to Very Confident in doing so. Post-survey, the number of students reporting that they were Confident or Very Confident increased by 30% indicating that many students that were Somewhat Confident increased their confidence levels.

Question 4 through 6 ask students about their ability to identify and leverage everyone’s interests, including their own, to reach an agreement. Such skills require not only knowing but doing. The simulation allowed students to practice and develop these skills, bolstering their confidence in their ability to employ them.

Conclusion

Overall, our data indicate that the simulation games help students acquire and improve their confidence using influence and negotiation skills in the context of complex sustainable development challenges, with students reporting increased confidence in their knowledge of and application of these skills. This increase in confidence is important because an individual’s actual ability to negotiate and influence an outcome is linked to what they believe about their ability (Bandura 1997). In addition, greater confidence is associated with greater motivation, persistence and patience, which are useful characteristics when navigating complex negotiations, such as those likely to be encountered in the sustainability field (Bandura, 1997 & 2011; Miles & Maurer, 2012).

Learning opportunities that challenge students and build resilience in an informative and supportive environment can help develop students’ self-efficacy (Bandura, 1997 & 2011). The simulation game provided students with a challenging, real-world negotiation where they could practice relevant skills. Students’ reported increase in confidence post-simulation suggests our pedagogical approach was effective.

Sustainable development and management of our resources is poised to become increasingly important and challenging as the impacts of climate change, economic development, and demographic shifts are realized. Each challenge will be unique in terms of its history, ecology, and stakeholders. To meet these challenges head on, we need leaders adept at using influence and negotiation strategies to forge a sustainable future. Virginia Tech’s Center for Leadership in Global Sustainability aims to develop in our students the influence and negotiation competencies they will need to lead this charge. Hofstede et al. (2010) note that simulation games are valuable in helping students develop the cognitive and emotional skills they will need to organize and lead change when the stress and risk are real and much greater. Our students develop, practice, and integrate such skills in a safe learning environment through a collaborative game that simulates a complicated, real-world problem (Hofstede et al., 2010). The results suggest that having even one opportunity to practice negotiations was helpful in building student’s confidence and that future experience will further increase their confidence. Therefore, we recommend this training for current and aspiring sustainability professionals and anyone interested in having influence on and helping negotiate sustainable development.

References

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. W.H. Freeman.

Bandura, A. (2011). On the functional properties of perceived self-efficacy revisited. Journal of Management, 38(1), 9-44. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0149206311410606 [10]

Brundiers, K., Wiek, A., & Redman, C. L. (2010). Real‐world learning opportunities in sustainability: from classroom into the real world. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 11(4), 308-324. https://doi.org/10.1108/14676371011077540 [11]

Colorado River Research Group. (2020, July). Reflections on two tumultuous decades in the Colorado River Basin. https://www.coloradoriverresearchgroup.org/uploads/4/2/3/6/42362959/crrg_reflections_on_two_decades.pdf [12]

Cotton, D., & Winter, J. (2010). ‘It’s not just bits of paper and light bulbs’: A review of sustainability pedagogies and their potential for use in higher education (pp. 54-69). In P. Jones, D. Selby & S. Sterling (Eds.), Sustainability Education. Earthscan. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781849776516-11 [13]

Dieleman, H., & Huisingh, D. (2006). Games by which to learn and teach about sustainable development: exploring the relevance of games and experiential learning for sustainability. Journal of Cleaner Production, 14(9-11), 837-847.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2005.11.031 [14]

Discovery Learning, Inc. (2013). Influence style indicator. https://oka-online.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/ISI-Sample-Individual-Report.pdf [15]

Dobson, H. E., & Tomkinson, C. B. (2012). Creating sustainable development change agents through problem‐based learning: Designing appropriate student PBL projects. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education,13(3), 263-278. https://doi.org/10.1108/14676371211242571 [16]

EPA. (2018, February 5). How We Use Water. https://www.epa.gov/watersense/how-we-use-water [17].

Evenson, E.J., Jones, S.A., Barber, N.L., Barlow, P.M., Blodgett, D.L., Bruce, B.W., Douglas-Mankin, K., Farmer, W.H., Fischer, J.M., Hughes, W.B., Kennen, J.G., Kiang, J.E., Maupin, M.A., Reeves, H.W., Senay, G.B., Stanton, J.S., Wagner, C.R., & Wilson, J.T. (2018) Continuing progress toward a national assessment of water availability and use. U.S. Geological Survey. https://doi.org/10.3133/cir1440 [18].

Guiu, R. (2020). When canals run dry: Displacement triggered by water stress in the south of Iraq. (J. Lennard, Ed.) The Internal Displacement Monitoring Center. https://www.internal-displacement.org/sites/default/files/publications/documents/202002-iraq-slow-onset-report.pdf [19]

Hmelo-Silver, C. E. (2004). Problem-based learning: What and how do students learn? Educational Psychology Review, 16(3), 235-266. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:EDPR.0000034022.16470.f3 [20]

Hofstede, G. J., De Caluwé, L., & Peters, V. (2010). Why simulation games work-in search of the active substance: A synthesis. Simulation & Gaming, 41(6), 824-843. https://doi.org/10.1177/1046878110375596 [21]

Hull, R. B., Mortimer, M., & Robertson, D.P. (2019). Developing cosmopolitan competencies in sustainability professionals. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 31(2), 346-353. http://www.isetl.org/ijtlhe/pdf/IJTLHE3402.pdf [22]

Hull, R. B., Robertson, D. P., & Mortimer, M. (2018.) Wicked leadership competencies for sustainability professionals: Definition, pedagogy, and assessment. Sustainability, 11(4), 171-177.https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/pdfplus/10.1089/sus.2018.0008 [23]

Hull, R. B., Robertson, D.P., & Mortimer, M. (2020). Leadership for sustainability: Strategies for tackling wicked problems. Island Press. `

Kharas, H. (2017). The unprecedented expansion of the global middle class: An update. The Brookings Institute. https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/global_20170228_global-middle-class.pdf [24]

Lozano, R., Merrill, M. Y., Sammalisto, K., Ceulemans, K., & Lozano, F. J. (2017). Connecting competences and pedagogical approaches for sustainable development in higher education: A literature review and framework proposal. Sustainability, 9(10), 1889. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9101889 [25]

Mankin, J. S., Viviroli, D., Singh, D., Hoekstra, A. Y., & Diffenbaugh, N. S. (2015). The potential for snow to supply human water demand in the present and future. Environmental Research Letters, 10(11), 114016.https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/10/11/114016 [26]

Miles, E.W., & Maurer, T.J. (2012). Advancing validity of self-efficacy in negotiation through focusing at the domain level. Journal of Occupational & Organizational Psychology, 85(1), 23-41.https://doi.org/10.1348/096317910×531744 [27]

Oregon State University. (2017, July 17). Global hotspots for potential water conflict identified. Science Daily. https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2017/07/170717160048.htm [28].

Perlstein, A., Mortimer, M., Robertson, D., & Wise, H. (2017). Making sustainable development real through role-play: “The Mekong game” example. Journal of Sustainability Education, 12. http://www.susted.com/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/Perlstein-et-al-JSE-Feb-2017-General-Issue-PDF1.pdf [29]

UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UNDESA). (2014, October 23). Transboundary waters. International Decade for Action ‘Water for Life’ 2005-2015. https://www.un.org/waterforlifedecade/transboundary_waters.shtml [30]

UN High Level Panel on Water. (n.d.). Transboundary water governance. United Nations.https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/hlpwater/04-TransbounWaterGovernance.pdf [31].

United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). (2017) Education for sustainabledevelopment goals: Learning objectives. UNESCO. http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0024/002474/247444e.pdf [32]

UN-Water. (n.d.). Water Facts: Transboundary Waters. https://www.unwater.org/water-facts/transboundary-waters/ [33]

UN-Water. (2008). Transboundary Waters: Sharing Benefits, Sharing Responsibilities. UN-Water Thematic Paper. https://www.unwater.org/publications/transboundary-waters-sharing-benefits-sharing-responsibilities/ [34]

UN-Water. (2018). Progress on Transboundary Water Cooperation – Global baseline for SDG indicator 6.5.2. UNECE and UNESCO. https://www.unwater.org/publications/progress-on-transboundary-water-cooperation-652/ [35]

Voiland, A. (2018). Cape Town’s Water is Running Out. NASA: Earth Observatory. https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/images/91649/cape-towns-water-is-running-out [36].

Welch, C. (2018, March 5). Why Cape Town is Running Out of Water, and Who’s Next. National Geographic. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/news/2018/02/cape-town-running-out-of-water-drought-taps-shutoff-other-cities/ [37].

Wiek, A., Withycombe, L. & Redman, C.L. (2011). Key competencies in sustainability: A reference framework for academic program development. Sustainability Science. 6, 203–218. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-011-0132-6 [38]

Wiek, A., Xiong, A., Brundiers, K., & Van Der Leeuw, S. (2014). Integrating problem-and project-based learning into sustainability programs. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 15(4), 431-449.https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSHE-02-2013-0013 [39]

World Resources Institute. (n.d.) Water: Mapping, measuring, and mitigating global water challenges. https://www.wri.org/our-work/topics/water [40].

Wray-McCann, Eileen. (2018, June 18). Speaking of Water – Water Conflict Chronology. [Audio podcast episode]. In Speaking of Water. Circle of Blue. https://www.circleofblue.org/2018/world/whats-up-with-water-speaking-of-water-water-conflict-chronology/ [41]