Abstract: Learning in the outdoors has significant educational advantages for children in the Primary School years and the need to connect with nature is becoming increasingly prominent in research worldwide. Pro-environmental behaviour, especially in the early years, has been shown to have a causal relationship with connectivity with the natural environment. Place-based outdoor learning promotes a relationship with the natural environment and constructs deep environmental knowledge and understanding of the world that surrounds learners. Embedding Indigenous culture and knowledge into outdoor learning within Primary School programs enables local knowledge and understanding to permeate throughout activities in explicit and experiential ways. A place-based pedagogy recognises the importance of forming intimate relationships with place through regular visitations to the same outdoor environment. One of the many global challenges confronting teachers working in Primary schools is how to implement holistic learning into their educational programs. This paper explores how an Australian case study utilises place-based outdoor learning and environmental sustainability within the school curriculum.

Keywords: connection with nature, place-based education, education for sustainability, environmental education

Introduction

During the early years of life and the formative years of schooling, children organise incoming information into something that makes sense to their worldview. To this end, Hall, (1997, p. 1), posits that “The information we consciously and unconsciously present to our children is of great importance for it is this which creates their reality and the morals and values which, as adults, they will live by, judge by, and may ultimately teach their children”. Children come to believe that the way they live their life is the right way, their beliefs, values and morals are the ones that should apply to the world. Accordingly, Davis (2008, p. 18), recognises that; “Experiences during this phase extensively influence physical and neurological developments, which drive biological, psychological and social responses throughout the human lifespan”. Based on this premise, there is overwhelming evidence to support the introduction of outdoor environmental education within the Primary years of schooling. Within these developmental stages the ideas of an individual’s lifetime are formed and active environmental sustainability morals can be inculcated. As such, experiential and place- based education play an integral role in Primary School education at the grassroots level.

The world is experiencing rapid growth and environmental issues are becoming ever more prominent in the social, political, economic and personal domains. Davis, (2008, p19), recognises that, “… various popular media has heightened awareness of how humans are over- stretching the earths life-support systems”. In the same vein, Hall (1997, p. 1) suggests that “… an introduction to environmental concepts, an understanding of basic human needs, an idea of the interrelationship of our habits and the rest of the ecosystem, and an affinity with the earth is essential to the developing child”. Primary School educators must consider that:

There can be few more pressing and critical goals for the future of humankind than to ensure steady improvement in the quality of life for this and future generations, in a way that respects our common heritage – the planet we live on. Education for sustainable development challenges individuals, institutions and societies to view tomorrow as a day that belongs to all of us, or it will not belong to anyone (UNESCO Education Sector, cited by Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts (DEHWA), 2010 p. 4).

The contemporary challenge for education is how to develop a generation of eco-warriors who become active citizens making lifelong informed environmentally sustainable decisions. Predicated on this stance, an educator’s responsibility to ensure that the sustainability platform occurs for all children in our schools (Kopelke, 2012; Loveridge, 2010). However, knowledge alone does not translate into a change in behaviour (Ellsworth, 2013; Gray & Birrell, 2013). A necessary precursor to environmental stewardship is deep love and affection for our planet (Orr, 1993). This idea is taken to further magnitude by Herbert (2008, p. 63) who espouses that “simply knowing about environmental issues has little impact upon behaviour. Knowing is not enough; children have to care enough to create harmonious relationships with the Earth and with fellow human beings”. It is evident that for the holistic development of environmental knowledge in children we must teach in, for and about the environment, using the guiding principles that were initially outlined in the report of the first UNESCO Intergovernmental Congress on Environmental Education in 1978, known as “The Tbilisi Declaration”, (UNESCO, 1978). Johnston and colleagues (2007, p. 4), recognise that, “The current fundamental conflict between ecological systems and human cultures does not mean that it is impossible for humans to co-exist with natural assemblages of organisms. It just means that this co-existence must be de- fined in the light of a new understanding of what is ‘right’ and what is demonstrably ‘wrong’ ”. The case for teaching environmental education for sustainability is clearly needed in the changing world we live in to embed in all of our children ways to sustainably co – exist with nature.

Teaching outdoors in a natural environment promotes an appreciation and lifelong connectedness to the environment (Gray & Martin, 2012; Hinds & Sparks, 2008; Louv, 2008). The Connection to Nature index developed by Cheng and Monroe (2010) measures enjoyment of nature, empathy for creatures, sense of oneness, and sense of responsibility. Their findings revealed that children’s connection to nature, previous experiences in nature, perceived family values towards nature, and perceived self–efficacy, positively influenced their interest in performing environmentally friendly behaviours. Knight, (2009) conducted research on Primary years outdoor education programs, such as the United Kingdom Forest School which promote an increased environmental knowledge and understanding. The formative years of a child’s education are the most influential time to foster an affinity with the natural world (Charles, Louv, Bodner & Guns 2008; Davies, 1996; Malone, 2004, 2007; Santer, Griffiths & Goodall, 2007). When children are provided with an opportunity to develop a sense of wonder, especially if nurtured by an attentive adult who facilitates and listens to the child’s inner life and own world, then rapid advancements can be made in developing ecological understanding.

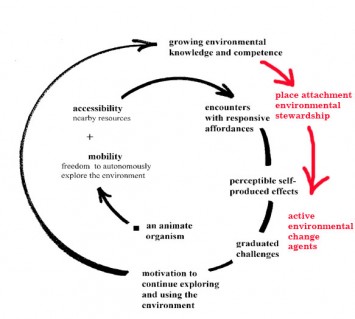

Chawla, (2007) has developed the “Positive interaction cycle of accessibility, mobility and engagement with the environment”, where the factors of accessibility, mobility and engagement combine to motivate individuals to go exploring, develop growing environmental knowledge and environmental competence. The cycle has been further adapted by Malone (2012, p. 22) to incorporate place attachment and environmental stewardship (see Figure 1). She proposes that the original cycle by Chawla, coupled with environmental knowledge and place attachment enable children to become active environmental change agents. Therefore, giving more insight into the worth of nature based outdoor education at an early age to form lifelong environmental morals.

[1]

[1]Figure 1: Positive interactive cycle of accessibility, mobility and engagement with environment leading to environmental change agency (Malone 2012 p. 30, adapted from Chawla 2007, p. 155)

Brown and Wattchow (2011) cite the environmental and outdoor education research studies of Haluza-Delay 2001; Haskell, 2000; Johnson, 2004 and Martin, 2005, to confirm that outdoor education is a means to relate to nature. During the Primary years, environmental outdoor education should be seen as a connecting children to nature in the outdoors environment to develop knowledge for and about the environment which in turns leads to a care of nature, lifelong learning and active citizenship. As a natural corollary, the core values of environmental education and education for sustainability are enhanced.

The world outside the classroom

Opportunities for children to actively engage in the outdoors are rapidly decreasing for a myriad of reasons such as urban design issues, less unstructured free-time, the fortification of homes and the advent of the screen-ager generation (Gray & Martin, 2012). The allure of indoor alternatives, such as computer games, television, social networking and the internet have curtailed children’s direct exposure to nature. Consider the following with reference to the changing opinions in the outdoors in the last 50 years:

There was a child went forth every day,

And the first object he look’d upon, that object he became,

And that object became part of him for the day or a certain part of the day,

Or for many years or stretching cycles of the years.

The early lilacs became part of this child,

And grass and white and red morning glories, and white and red clover,

and the song of the phoebe-bird,

And the Third-month lambs and the sow’s pink-faint litter,

and the mare’s foal and the cow’s calf……….

WALT WHITMAN

(Louv, 2008, p. preface)

And the more recently written:

I like to play indoors better ‘cause that’s where all the

electrical outlets are.

A FOURTH-GRADER IN SAN DIEGO

(Louv, 2008, p. preface)

The second quote is reflective of people’s attitudes of the outdoor world today, in his book, Last Child in the Woods, Louv, (2008), articulates the changing face of society where our children are more likely to be indoors than out. This is a distinct change from when the first quote above was written 50 years ago. In today’s fast paced and materialistic society there is little time for children to have loose, unstructured dreamtime – to experience nature in a meaningful and therefore internalised way. The term nature deficit disorder has been defined by as Louv (2008 p. 36), “The human cost of alienation from nature, among them: diminished use of the senses, attention difficulties, and higher rates of physical and emotional illness”. Louv, (2008), continues to explain that this disorder can change the behaviour of people, crime rates, depression and other social issues. Research from within the United Kingdom education system has also realised that, “Contact with the outdoors is often limited for many children in modern society and the vital experience of using the outdoors and being comfortable is being lost” (O’Brien & Murray, 2006 p. 5).

Our nature estranged lifestyle is a cause for concern for parents, teachers and health care professionals alike (Gray, 2005; Townsend & Weerasuriya, 2010). In Australia it is becoming increasingly evident that children are not spending time in the outdoors and that connection with nature is also being lost. Data from “Who Cares about the Environment in 2009?” (Department of Environment Climate Change and Water (DECCW), 2010), states that the percentage of respondents overall who participate in environmental activities was generally under 50%. It was noted that, “activities beyond the household that require the most effort had the lowest participation” (2010, p. 74).

This being said, Townsend and Weerasuriya (2010) purport that the lack of time spent in the outdoors can be overcome as accessible green spaces are part of the solution to people’s estrangement from the outdoor natural world. However, making these green spaces accessible to all has issues in today’s society due to concern of children being unsupervised in the outdoors. Herbert (UNESCO, 2008, p. 65) explains the disconnection with the outdoors simply by saying, “In less hurried and fearful times, playing unsupervised outdoors, exploring nature, climbing trees and collecting natural objects were all regarded as ‘play’, but built solidly on how the world works”. The Primary school curriculum worldwide can step in here and increase young people engagement with their local environments by including it in a structured and supervised way by teachers.

The interdisciplinary, problem solving, inquiry based and holistic pedagogical approaches to learning common in Primary schools are promoted throughout the UNESCO (2011) “Education for Sustainable Development: Review of process and learning”. Herbert (UNESCO, 2007, p. 64) promotes that, “Nature is a wonderfully interdisciplinary, everything is woven together and given meaning by seeing it in its context and observing it over time. Engagement through exploration with these aspects of the local environment helps a child gradually develop eco- literacy or eco – intelligence”. Cutter Mackenzie and Smith (cited by Fagerstam, 2012, p. 2) argue that the objective of Orr’s theory of ecological literacy is to develop not a particular view of the environment, “but a complex understanding of various philosophies that lead to ecological sustainability”. In the same vein, it can be asserted that engaging with the natural environment leads to eco–literacy that in turn, develops children’s understanding of environmental sustainability.

Teaching aspects of environmental education in the outdoors is simply one way to establish deep learning and connection to place for children to develop eco–literacy, which includes concepts of environmental sustainability (Miles, 2013). According to Birrell and colleagues (2013) new understandings of pedagogy are emerging to support this claim. Davis (UNESCO, 2011), cites outdoor experiential play and learning as significant contributors to children’s overall development and learning. Ballantyne and Packer’s 5th Pedagogy, cited in Tooth and Renshaw (2009) believe in the educational advantages of an experience-based pedagogy that they outline as;

“Being in the environment students are encouraged to experience and appreciate the special characteristics of the natural environment; Real life learning – learning activities based on real places, real issues, and authentic tasks; Sensory engagement opportunities provided to explore the environment using all five senses; Learning by doing students actively involved in hands-on exploration and investigation; Local context students encouraged to explore and investigate environmental problems and issues in their own backyard” (Tooth & Renshaw, 2009, p. 4).

The work of Wattchow and Brown, (2011) in their book Pedagogy of Place, strengthens the argument of teaching in the outdoors and connecting children with local areas of land on a regular basis. Practically speaking this land can be on the school grounds or close to it, and in a country with so much green space there is real potential for this to happen seamlessly in many situations. The beauty of the Primary aged learner is that the space does not have to be large or be so called wilderness, it just needs to be somewhere where the children can learn, wonder, play and explore. Edges of ovals, city parkland, nature reserves, National Parks adjoining schools; the spaces used for outdoor learning are only limited by the sense of innovation of the teacher. When the author was faced with the issue of her local council owned reserve being built on by the extensions of the local regional hospital outdoor learning had to be moved onto school grounds. Where there is a will there is a way being the key message here.

Outdoor Learning Implications – the Indigenous Perspective

The implementation of environmental and outdoor education programs world-wide should take into account the local Indigenous populations and the history of our land and ‘country’. The following poem introduces the relationship of the Australian Indigenous peoples relationship with the land and the importance of the outdoors in teaching our Indigenous students to foster this link to the natural world.

This ground never move, I’ll be buried here.

I’ll be with my brother, my mother.

If I lose this,

Where I’ll be buried?

I’m hanging onto this ground.

I’ll become earth again.

I belong this earth.

And earth should stay with us.

Tree the same as me.

When he get old he’ll die…..

Tree become earth…

Rock stays,

Earth stays.

I die and put my bones in cave or earth.

Soon my bones become earth…

all the same.

My spirit has gone back to my country….

My mother.

(Neidjie, 1986, cited in Dickson, Gray & Hayllar, 2005, p. 32)

Considering that “Indigenous cultures all over the world understand and embrace their connection with all life, beings, existence and time. Intrinsic within these systems is the Indigenous Australian concept of ‘Dreaming’, which is about people’s origin, path and destiny” (Ellis- Smith, cited in Dickson, et al, 2005, p. 70), Indigenous story is the ideal starting point to place based education. It could be seen as the ultimate connection to place and the true localisation of any outdoor learning program. “Stories bring nature into culture and ascribe meaning to places, species and processes which would otherwise remain silent to the human ear” (Sinclair, cited in Wattchow & Brown, 2011, p. 189).

[3]

[3]Figure 2 and 3 show an Indigenous classroom teacher at our school reading the local dreaming story of the Black Cockatoo from a book made by Indigenous students at the school to her Year 1 students. The students have collected the items to make a large black cockatoo nest. It is the beginning activity to set the scene for a day of outdoor learning facilitated by the classroom teachers.

Outdoor learning can include traditional bush crafts and develop skills across a broad range of subjects, combining hands on learning in nature and follow up bookwork back in the classroom. Many Indigenous people are choosing to educate others about their culture in an effort to increase cultural awareness and decrease discrimination, (Ellis- Smith, cited in Dickson, et al. 2005).

Learning outside the traditional classroom is a valuable tool to assist learning outcomes of Indigenous learners themselves. Learning environments can be developed throughout schools to assist Indigenous learners social, academic and emotional learning, “Outdoor classrooms, learnscapes and trails provide avenues for Indigenous students and parents to participate and feel welcome within the school without being restricted to the classroom environment. Outdoor classrooms also enable bush foods and native gardens to be integrated into the school setting” (Queensland Government Department of Education and the Arts, 2005, p. 10). Partnerships with Indigenous locals in facilitating outdoor education experiences are an excellent way to invite community members into schools, their knowledge and practice in the outdoors being invaluable. In the Australian Indigenous Education Action Plan, (2010, p. 9), it says, “A sense of cultural identity, and the active recognition and validation of Indigenous cultures by schools, is critical to student wellbeing and success at school”. It is when all these factors combine that an Indigenous component to outdoor environmental learning is authentic. The inclusion of Indigenous perspectives is in fact vital to increase the knowledge of the wider population in Indigenous ways.

A Worldview Perspective

In the United Kingdom the world outside the classroom is seen as integral in the implementation of government initiatives that focus on improving children’s well being. The Education Outside the Classroom Manifesto, (O’Brien & Murray, 2006, p. 5), was published to “highlight that education outside can motivate pupils and bring learning to life”. The implementation of outdoor learning in a natural environment is being integrated into the curriculum for children aged 3–19 years in the United Kingdom. The Forest School movement is an example where outdoor education is evident within the United Kingdom school system. They have a large emphasis on experiential learning, self directed play and exploration in a safe and supportive natural environment. The philosophy of Forest School is to encourage and inspire individuals of any age through positive experiences and participation in engaging and motivating achievable activities in a woodland environment, helping to develop personal, social and emotional skills such as; independence, self-discovery, confidence, communication skills and raised self-esteem (Archimedes Training, 2008).

Forest School practitioner and researcher, Sarah Knight, in her book, “Forest Schools and Outdoor Learning in the Early Years” (2009) describes a Forest School under the following headings:

1) The setting is not the usual one (i.e. not the general learning space or generally used playground).

2) The Forest School is made as safe as is reasonably possible, in order to facilitates children’s risk taking.

3) Forest Schools happen over time – in averaging six weeks of one half-day block.

4) There is no such thing as bad weather, only bad clothing.

5) Trust is central.

6) The learning is play- based, as far as possible, child-initiated and child-led.

7) The blocks of sessions have beginnings and ends.

8) The staffs are trained. (Knight, 2009, p. 15 – 17)

Forest School Programs run throughout the year going to the woods in all weather with the children wearing protective clothing. Children use full sized tools, play, learn boundaries of behavior; both physical and social, grow in confidence, self-esteem and motivation. Programs are developed by Forest Schools trained leaders and can sit within or completely external to the regular school curriculum. While teachers attend with their class, they may not be the leader facilitating the session.

The criteria for eco–literacy development as developed by Herbert, (UNESCO, 2008), offers many similarities to the Forest School ethos and criteria (Archimedes, 2008 and Knight, 2009). Herbert (UNESCO, 2008, p. 64), outlines the development of early childhood eco literacy as developing the following opportunities to:

* develop many varied learning experiences integrating many knowledge areas.

* allow unstructured time – time “to be” and to contemplate, in a natural setting.

* observe changes in an environment over time.

* play a valued part in real life activities.

* use tools and begin to develop practical skills.

* engage in physical challenges and test one’s limits.

* develop collaborative, investigative and critical thinking skills.

* encouragement of a sense of wonder about the natural world.

Long term repeated connection to place, as place has to do with the relationships between people, setting and activity and a lack of sufficient time in one place makes it impossible to experience it authentically (Wattchow & Brown, 2011). A study of the effectiveness of Forest Schools undertaken by Knight, (2009, p.57) surveyed the parents of children participating in Forest School sessions. Parents observed the following in their children after having visited the same woodland on a regular basis:

- Increased confidence and self esteem

- Increased social skills

- Improved language and communication skills

- Improved motivation and concentration

- Improved physical skills

- Increased environmental knowledge and understanding.

Travlou, 2006 (cited by Townsend & Weerasuriya, 2010), researched the benefits from experiential outdoor play and adventure in natural settings and found similar physical, social and educational benefits to the findings of Knight (2009). The study highlighted specific benefits to the current social and educational climate, noting the heightened academic learning as a result of practical experiences, the acquisition of language development and the development of ecological consciousness. With the pending implementation of a new Australian National Curriculum these are areas that are currently being under scrutiny from educational researchers for further development. There is significant anecdotal research completed by each facilitator of outdoor learning programs and this body of evidence should increase over the coming years.

Implications for experiential place based learning Primary Schools?

As teachers we aim to educate the whole child, to cater for individual differences and make learning “real”. The question could be asked what is “real” today? With the changing face of the world’s population there is an increased awareness of the importance of the environment we live in. However the reality is that interactions with this environment are decreasing and the environment is being destroyed. There is no doubt that curriculum pressures, educational reform, systemic education, globalising forces and international perspectives, (Wattchow & Brown, 2011), are limiting the implementation of outdoor environmental education.

Louv, (2008, p. 226) states that, “ An environment-based education movement – at all levels of education- will help students realise that school isn’t supposed to be a polite form of incarceration, but a portal to the wider world”. Preparing students for the wider world is about teaching life skills as well as other more traditional academic skills. By getting our students outdoors we are teaching much more than environmental awareness, but also important benefits like the increased risk taking strategies learnt, health advantages from being outdoors, Indigenous cultural awareness and the development of various learning styles. It is teaching not simply about the environment, it is teaching in and importantly for the environment to create a hopeful lifelong respect for the world in which we live for our students. We need to start exposing our children to the benefits of nature to ensure that they become eco–literate, (Herbert, 2008), and move into the environmental action stage of the learning cycle proposed by Chawla (2007) and Malone, (2012).

Unquestionably, the importance of place-based environmental education in the Primary years of schooling cannot be denied. The governing educational bodies worldwide must recognise the powerful role that an early education in the environment plays for laying the foundation to develop active and responsible citizenship in terms of environmental sustainability. The potential for interdisciplinary, inquiry- based learning can achieve beneficial holistic learning gains for our students, (UNESCO, 2008).

Outdoor education is an aspect of environmental education for sustainability and at the Primary School level this is primarily connected with immersion in nature. Whilst there are already initiatives in place in this area it is my firm belief that there needs to be a concentrated effort so that all children can benefit and strive to reach their individual highest potential of understanding of the environment. There can be no doubt in the value in promoting the life long learning that connecting to place initiates, as Wattchow and Brown, (2011, p. 91), poignantly state, “Places are pedagogically powerful”.

“The message is urgent: unplug, boot it down, get off-line, get outdoors, breathe again, become real in the real world”,

David Orr (cited by Louv, (back cover) 2011).

Amanda Lloyd is a Primary School teacher and PhD student at UWS. Her research interests are focused on place- based outdoor education within an integrated school curriculum.

Tonia Gray is an Associate Professor in the Centre of Educational Research in the School of Education at UWS. Her research interests include: eco-pedagogy, human-nature relationships and reflection and experiential learning in a variety of educational settings.

References

Archimedes Training. (2008). Forest Schools OCN Level 3 Handouts and Portfolio. Sheffield: Archimedes Training ltd.

Birrell, C., Gray, T. Preece, M. & Ely, D. (2013). Ecopedagogies: Ways of connecting with the natural world through the Arts. Paper presented at the Linking Art and the Environment: EcoArts Australis Conference, 12-13 May 2013, Wollongong, NSW.

Charles, C., Louv, R., Bodner, L. & Guns, B. (2008). Children and Nature 2008: A report on the movement to reconnect children to the natural world. New Mexico: Children and Nature Network.

Chawla, L. (2007). Childhood Experiences Associated with Care for the Natural World: A Theoretical Framework for Empirical Results. Children, Youth and Environments 17(4): 144-170. Retrieved 1 [4] from http://www.colorado.edu/journals/cye [5].

Cheng, J. & Monroe, M. (2010). Connection to Nature: Children’s Affective Attitude Toward Nature. Environment and Behaviour. 44(1), 31 – 49.

Davies, M. (1996). Outdoors: An important context for young children’s development. Early Child Development and Care, 115 (1), 37-49.

Davis, J. (2008). What might education for sustainability look like in early childhood?

– A case for participatory, whole-of-settings approaches. The contribution of early childhood to a sustainable society. UNESCO, p 18 – 25.

Department of Education and Training (DET) (2010). New South Wales Indigenous Education Plan. Retrieved: 11October, 2012, from: https://www.det.nsw.edu.au/policies/students/access_equity/aborig_edu/PD20080385.shtml [6]

Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts (DEWHA), (2010). Sustainability Curriculum Framework. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.

Department of Environment, Climate Change and Water (DECCW) NSW. (2010). Who Cares – about the Environment in 2009? Sydney: DECCW.

Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts. (2009). Living Sustainably. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.

Dickson, T., Gray, T. & Hayllar, B. (2005). Outdoor and Experiential Learning. Views from the top. Dunedin: Otago University Print.

Ellsworth, M. (2013). When logic isn’t enough: Science + Arts = Action. Keynote paper presented at the Linking Art and the Environment: EcoArts Australis Conference, pp 14-15. 12-13 May 2013, Wollongong, NSW.

Fagerstram, E. (2012). Children and Young People’s Experience of the Natural World: Teachers’ Perceptions and Observations. Australian Journal of Environmental Education. 28(1), 1-16.

Gough, A. (2011). The Australian–ness of Curriculum Jigsaws: Where Does Environmental Education Fit? Australian Journal of Environmental Education. 27(1) 1-15 http://mams.rmit.edu.au/fflmjbc79nj81.pdf [7]

Gray, T. (2005). Exploring Our Connections And Relationships With Place And/Or Nature, in Dickson, T. Gray, T. and Hayllar, B. (2005). (Otago University Press) Outdoor and Experiential Learning: Views From The Top. pp 9-12.

Gray, T. & Birrell, C. (2013). Touched by the Earth: The impact of a multi-sensory immersion program on Year 7-8 students. International Outdoor Education Research Conference, Dunedin, New Zealand 25-29 Nov.

Gray, T. & Martin, P. (2012). The Role and Place of Outdoor Education in the Australian National Curriculum, Australian Journal of Outdoor Education. 16 (1) 39-50.

Hall, A. (1997). Practical approaches to programming primary outdoor education. Retrieved 14 October, 2012, at: http://voea.vic.edu.au/publications/journeys/primaryoutdoored_hall.html [8]

Herbert, T. (2008). Eco–intelligent education for a sustainable future life. The contribution of early childhood education to a sustainable society. UNESCO. pp. 63 – 67.

Hinds, J. & Sparks, P. (2008). Engaging with the natural environment: The role of affective connection and identity. Journal of Environmental Psychology [9] Vol 28, No. 2 [10], pp. 109–120

Johnston, P., Everard, M., Santillo, D. & Robert, K. (2007). Reclaiming the Definition of Sustainability. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 14 (1), 60–66.

Kollmuss, A. & Agyeman, J. (2002). Mind the gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behaviour? Environmental Education Research, 8(3), 239-260.

Kopelke, D. (2012) Environmental Education through Listening to Children. Doctor of Education Thesis: Queensland University of Technology.

Knight, S. (2009). Forest Schools and Outdoor Learning in the Early Years. SAGE publications, London.

Louv, R. (2008). Last Child in the Woods. Saving Our Children From Nature-Deficit Disorder. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: Algonquin Books.

Louv, R. (2011). The Nature Principle. New York: Algonquin Books.

Loveridge, J. (Ed). (2010). Involving children in research in educational settings. Wellington: Ministry of Education New Zealand.

Maller, C., Townsend, M., St Leger, L., Henderson-Wilson, C., Pryor, A., Prosser, L. & Moore, M. (2008). Healthy parks, healthy people: The health benefits of contact with nature in a park context. Report by Deakin University and Parks Victoria.

Malone, K. (2012). The future lies in our hands: children as researchers and environmental change agents in designing a child-friendly neighbourhood, Local Environment: The International Journal of Justice and Sustainability, DOI:10.1080/13549839.2012.719020

Malone, K. (2007). The Bubble-wrap Generation: Children growing up in walled gardens. Environmental Education Research, 13 (4), 513-527.

Malone, K. (2004). Holding Environments: Creating spaces to support children’s environmental learning in the 21st century. Australian Journal of Environmental Education, 20 (2), 53-66.

Martin, P. (2005). Human to Nature Relationships Through Outdoor Education. In T.J. Dickson, T. Gray & B. Hayllar (eds), Outdoor and Experiential Learning: Views form the top (pp.28-52). Dunedin, New Zealand: Otago University Print.

MCEETYA. (2008). Melbourne Declaration on Educational Goals for Young Australians. Melbourne: Ministerial Council on Education, Employment, Training and Youth Affairs

Miles, R. (2013). Experiencing sustainability education through place: A case-study from rural- regional Australia. Journal of Sustainability Education. 5, May.

National Curriculum Board. (2009). The Shape of the Australian Curriculum. Barton, ACT: Commonwealth of Australia.

O’Brien, L. & Murray, R. (2006). A marvellous opportunity for children to learn. A participatory evaluation of Forest School in England and Wales. Surrey: Forest Research.

Orr, D. W. (1993). Love It or Loose It: The Coming Biophilia Revolution. In: The Biophilia Hypothesis (Ed. by Kellert, S. R. and Wilson, E. O.), pp. 425-440. Shearwater Books/ Island Press, Washington, D.C.

Santer, J., Griffiths, C. & Goodall, D. (2007). Free Play in Early Childhood: A Literature Review. London: National Children’s Bureau.

Townsend, M. & Weerasuriya, R. (2010). Beyond Blue to Green: The benefits of contact with nature. Deakin University.

Tooth, R. & Renshaw, P. (2009). Reflections on pedagogy and place: a journey into learning for sustainability through environmental narrative and deep attentive reflection. Australian Journal for Environmental Education, Retrieved 14 October, 2012, from: http://www.thefreelibrary.com/Reflections+on+pedagogy+and+place%3A+a+journey+into+learning+for…-a0219003770 [11]

UNESCO – UNEP. (1978). The Tbilisi Declaration. Connect. UNESCO – UNEP Environmental Education Newsletter, III (1), 1 – 8.

UNESCO. (2011). Education for Sustainable Development: An expert review of Processes and Learning. Paris: UNESCO.

Wattchow, B. & Brown, M. (2011). Pedagogy of Place. Victoria: Monash University Publishing.

- 6.12 ↩ [12]