PDF: BrookeMoranSpring2013 [2]

Abstract

Engaging employees in social and environmental sustainability initiatives “…can improve a business’ bottom line and help it reach its sustainability goals” (NEEF, 2011, p. 14). While some organizations may have sensed this years ago, most are only recently acknowledging how critical employee engagement is to their ultimate success. Presumably, this realization is partially due to findings that between 92% (Dunn, 2007) and 96% (Johnson Controls, 2010) of “Millennials” want to work for environmentally conscious organizations; they are highly concerned about the environment and expect their employers to become more sustainable. Additionally, Gallup (2009) discovered employee engagement to be the “leading indicator of financial performance” and Hewitt Associates (2010) found a strong correlation between employee engagement and environmentally and socially responsible organizations – the former garnering considerable attention in the corporate sector. Logically, this has led to many organizations both trying to weave social and environmental values and practices into their daily operations and hiring people with experience that will speak to this trend (e.g., sustainability knowledge and experience). This has put engaging employees at the forefront of Sustainability Directors’ priorities. However, because this is a relatively new pursuit, there is limited information on how to achieve this aim. As such, this article sets forth means of engaging employees in social and ecological sustainability initiatives with varying levels of experientiality (Gibbons & Hopkins, 1980) through the lens of a new model for employee engagement.

Keywords: employee engagement,sustainability,experiential education

Introduction

Engaging employees in social and environmental sustainability initiatives “…can improve a business’ bottom line and help it reach its sustainability goals” (NEEF, 2011, p. 14). While some organizations sensed this decades ago, most are only recently acknowledging how critical employee engagement (EE) is to their values, operations, advancement of sustainability, and ultimate success. Presumably, this realization is partially due to findings that between 92% (Dunn, 2007) and 96% (Johnson Controls, 2010) of “Millennials” want to work for environmentally conscious organizations; they are highly concerned about the environment and expect their employers to become more sustainable. Additionally, Gallup (2009) discovered EE to be the “leading indicator of financial performance” and Hewitt Associates (2010) found a strong correlation between EE and environmentally and socially responsible organizations – the former garnering considerable attention in the corporate sector. Logically, this has led to many organizations both trying to weave social and environmental values and practices into their daily operations and hire people with experience that will speak to this trend (e.g., sustainability knowledge and experience). “Companies recognize that greening their products and operations is a source of value and that all employees must be engaged in the effort to ensure its success” (NEEF, 2011). These insights, combined with customers’ behaviors and demands, have resulted in organizations hiring Sustainability Directors (SDs) and Chief Sustainability Officers (CSOs). A priority for these positions is to engage employees in the process of enhancing social and environmental sustainability. However, because this is a relatively new pursuit, there is limited information on how to achieve this aim. As such, this article sets forth means of engaging employees in social and ecological sustainability initiatives with varying levels of experientiality (Gibbons & Hopkins, 1980). Specifically, the following three sections comprise this paper: 1. creating an organizational scaffolding for employee engagement; 2. introducing and detailing a model for EE; and 3. providing specific strategies and suggestions for experientially engaging employees in social and ecological sustainability initiatives.

Organizational Scaffolding for Employee Engagement

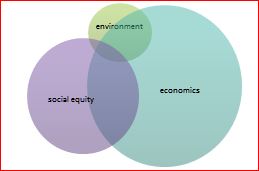

The strategies and suggestions for engaging employees outlined in the final section of this paper work best in organizations that subscribe to triple bottom line (TBL) (Elkington, 1994; Savitz, 2006), Cradle to Cradle (McDonough & Braungart, 2002), The Natural Step, Caux Roundtable or another kindred set of guiding principles. No matter what framework is used, it is crucial to have an integrated strategic plan[i] [3] (ISP) and an aligned sustainability task force[ii] [4] (STF) that actively embraces environmental, social, and economic sustainability. (For consistency’s sake, TBL will be used henceforth, as it is commonly known – even for those new to sustainability.) However, many of the strategies and suggestions offered in the final section of this paper can also be useful to mid-managers who initially have little leverage within an organization that has an economically-centered strategic plan. That being stated, an operating paradigm of this article is that organizations ought to strive for a TBL approach. TBL Venn diagrams are usually presented with three equally sized, overlapping circles. Until that equilibrium is attained (e.g., via an ISP), attention will likely oscillate between the three areas as policy, economic pressures, environmental strategy, business trends, and/or various leadership forces push against each other. An example of this inequitable TBL is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Inequitable Triple Bottom Line. In this example, economic concerns garner more attention than social equity issues, which garner more attention than the environmental ones. As such, in this example, economics would prevail over social equity and the environment for decision-making. This approach is not sustainable.

Coca-Cola provided a salient example of this inequity at its Plachimada, India plant. Coca-Cola primarily focused on economics – that is, making money and providing jobs – in its production process, which entailed extracting roughly 1.5 million of liters of water every day from the local aquifer to produce its beverages. This depleted the ground water on which the local farmers relied, which caused a major social disturbance. Hindsight (and maybe foresight by some) makes it clear that emphasizing economics over social equity and the environment was not an economically sustainable strategy, as Coca-Cola faces a US$48 million State Government of Kerala tribunal for agricultural losses, health problems, loss of wages, etc. (India Resource Center, 2010).

While some individuals and organizations are intrinsically motivated, others may be prompted to change due to external catalysts, such as the example above, negative publicity due to the utilization of child labor, poor working conditions, or rising transportation prices. However, external catalysts do not tend to result in an integrated approach to sustainability because as external pressures shift, the motivation to act shifts or falters. Or as one problem is solved, another takes precedence. Linville and Fischer (1991) coined the phrase “finite pool of worry”, which describes the phenomenon wherein people can only worry about so many things at one time. Like any strategic plan, an ISP that is positioned for success is viewed as a long-term endeavor, for society, business and personnel are ever-changing, particularly in a global context. As such, an ISP is more likely to stay within a finite pool of worry than non-integrated strategic plans.

In addition to having an ISP, a STF is an incredible asset for engaging employees in the advancement of sustainability. Whether in an educational institution or a corporation, people see initiatives come and go and can get complacent about buying into changes; Werbach (2009) terms this “initiative fatigue.” As such, employees need continual exposure to a unified message that sustainability is becoming integral to the organization’s vision and operations. This messaging requires more than memos; it needs to be continually modeled and addressed by the STF. A well-publicized and highly criticized contrary example saw Ford and General Motors executives taking private jets to government hearings and asking for bailouts. Inconsistent messaging is an ineffective change strategy, though a great way to disengage employees. Likewise, if the Chief Sustainability Officer (CSO), Sustainability Director or the ilk consistently provides messaging about increasing sustainability efforts, but the CEO emphasizes success only via economic benchmarks, employees will see a divided leadership team and generally side with the familiar strategy and the executive who signs their checks. A STF with consistent messaging is crucial, no matter what the size or specialization of the organization, especially in preparation to reposition within the market when faced with marketplace disruptions or other challenges.

In addition to a STF, another means of clear messaging regarding the integration of sustainability is to consider an organizational restructuring that adds a sustainability position to the C-Suite in corporations or Cabinet in institutions of higher education, an example of which is depicted in Figure 2. Not only is this approach practical, as the CSO has access to both the STF and executive level to collaborate and problem-solve, but it also sends a message to the executive team, employees, consumers, and investors about changing values.

Figure 2. Sustainable Organizational Model.

Without an aligned leadership team (i.e., STF and executives) championing the ISP, there are diminished opportunities for engaging employees in the advancement of sustainability, which research suggests may result in less than desirable financial performance.

Engaging Employees

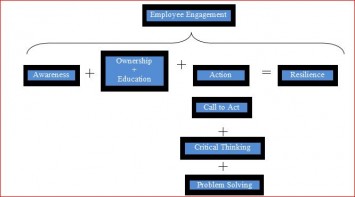

A model for employee engagement[iii] [7] is depicted in Figure 3, the components of which are described in more detail below.

Figure 3. Process of Engaging Employees. Employee engagement starts with a low level of experientiality, which increases with each phase. Awareness leads to taking Ownership and deepening Education, which leads to Taking Action. The latter necessitates a Call to Act, the ability to Think Critically, and Problem-Solve, the latter inherently necessitating reflection, an integral component of experiential education. Engaged and reflective employees tend to be more resilient ones, and resilient employees lend to creating a resilient organization.

Awareness

Awareness is a critical first step in engaging employees in any initiative and can be catalyzed in myriad ways. For example, a memo might help employees become aware that the organization has decided to pursue sustainable operations; this is a very low-level of awareness – one that may not have an impact on the individual employee (if it even gets read). Some people gain a new perspective by listening to a respected friend or colleague, whether a friend’s success story or emerging awareness. “In the case of Ball Corporation, when sustainability started to become a hot topic in the packaging industry, Ball Corporation took notice. The company hired a consultant and after senior executives were given a presentation on The Triple Bottom Line (Savitz, 2006), the concept of the TBL approach to business was adopted” (2011, Geraldine Walsh, personal communication). Others’ awareness may be piqued by being forced into action (note external motivation) via organizational operations/protocol before a tipping point (Gladwell, 2000) occurs and intrinsic motivations for sustainability generate action.

Intrinsic motivations, catalyzed by emotions or personal experience, have staying power. Chouinard (2005), founder and owner of Patagonia, Inc., is also an avid surfer, rock climber, and fisherman. Through engaging in these pursuits, he saw his and others’ negative environmental impacts, such as the scars that pitons left on rocks. Knowing that clothing manufacturing had detrimental environmental and social effects, in 1991 Patagonia launched an assessment program and conducted life-cycle analyses on their most popular fibers. One outcome was to use the farthest downstream Portuguese dye house on the Porto river for their flannel shirts; it was the only one that was taking the highly polluted and black water (from the dye houses upstream) and cleaning it not only prior to using the water, but also cleaning it again before putting it back into the river – unlike the other dye houses. As such, the water was cleaner after dying Patagonia’s clothes than it was before. It stands to reason that all of the time Chouinard spends surfing and fishing in rivers and the ocean, as well as his emotive tie to such places, factored into his concern for the Portuguese waterway. Chouinard’s and Patagonia’s action became a tool of awareness and engagement for Patagonia’s employees and customers, as well as other retailers and manufacturers in the industry. Others’ concerns are catalyzed by a change in perspective. Often people talk about having children and then realizing that they want their offspring to have clean water to drink and play in, clean air to breathe and forests in which to explore. These intrinsic, emotive catalysts have staying power.

Clearly, employees at all levels of an organization are going to have varying levels of investment in sustainability. As such, a listening tour can be a tool to both raise employees’ awareness about sustainability and to help the STF understand how to best approach various individuals and/or organizational sectors. A listening tour is an insightful exercise that entails soliciting people’s input and then listening to their ideas and concerns, current practices, and gauging the existing levels of interest and ownership. A proper listening tour is a face-to-face endeavor with key people, but could also include conversations via Skype, or a survey to gauge the general sentiment of employees. It will reveal who are allies and who might be negative distracters in the implementation process. The listener will gain insight into the negative distracters’ currency (e.g., recognition, money, challenge), which might provide ideas for garnering buy-in at a later date. Conversely, leaders can tap into emotions and social relationships when they share their stories regarding why sustainability is important to them and create compelling reasons for others to join the cause. Orr (1992) asserts that spending time in nature is one of the prerequisites to being ecologically literate. This rings true in reality, as many environmental and social champions have a story about a personal experience that profoundly changed them and helped shape their world view – whether that was spending time in nature as a child, being an avid fisherman as an adult and encountering polluted waters, seeing social injustices via third-world travel, or witnessing rain forest destruction first-hand. No matter what the tactic, engaging employees in the advancement of sustainability is crucial. Additionally, innovative ideas regarding increasing efficiencies, decreasing waste, or sustainable products, and the ilk will come from people who know their divisions best. They might not share any novel or innovative ideas during the listening tour, but at the very least, 1. they will know who to contact with future ideas; and 2. they will know that they – and their job – matter. Upon conclusion of the listening tour, any requisite augmentations to the STF membership will become apparent. It is ideal to have a representative from each sector/department to aid in two-way communications, as well as to generate ideas and buy-in from all angles.

Creative means for raising awareness is encouraged, as innovative strategies tend to garner attention. In addition to the strategies and suggestions offered in the final section of this paper, a unique awareness-raising example follows. During Davidson College’s Year of Sustainability, students shaped a model airplane out of chicken wire and filled it with hundreds of cans. The sign above it read “Americans throw away enough aluminum cans to rebuild our commercial air fleet every three months.” This approach may not work for all organizations, but creatively bringing various facts to life is an effective means of raising employees’ awareness and encouraging their engagement in ownership and education opportunities.

Ownership and Education

People want to learn about and become involved in sustainability. Talk shows have green days or weeks; stores promote reusable water bottles, coffee mugs, and/or cloth grocery bags; Community Supported Agriculture and farmers’ markets have increased dramatically in past years, allowing people to eat more healthily while supporting small, local farms; environmental service learning is integral to many public and private schools, from Kindergarten through undergraduate programs. In addition to statistics shared in the introduction, 82% of U.S. Adults think business leaders need to learn more about the environment (University of Wisconsin, 2010). These survey findings suggest that every organization – be they educational or corporate – ought to consider sustainability and employee engagement as integral to that aim.

Taking ownership and providing educational opportunities to help inform future action is paramount to engaging employees. In some cases, ownership might catalyze the need for further education, while in others education might lead to ownership. In the case of Chouinard and other Patagonia employees visiting the dye houses in Portugal, witnessing the black fluid pouring into the river allowed Patagonia the awareness and education that led to ownership and action. Not taking ownership entails pointing fingers and/or justifying. On an individual or organizational level, soliciting feedback and feedforward (Goldsmith, 2007) helps individuals and organizations take ownership and pinpoint areas for growth and strategies to do so. Feedforward entails describing a problem to a trusted colleague or mentor and asking for proactive suggestions to rectify the problem; simply articulating the problem suggests that there is already some level of ownership. Soliciting feedback entails asking for both positive and constructive comments on performance. Again, being open to receiving feedback suggests that the solicitor wants to improve. Once an individual or organization has taken ownership of her/its actions, opportunities for education abound. However, for some, taking ownership may come after the process of education begins.

To those wondering how, where, and to whom to turn for sustainability education, the answer is to uncover all effective means, everywhere, all of the time. People can learn from whomever has something to teach – nemeses (only if one has an open mind), trusted colleagues, employees, executive team members, children, elderly people, external consultants, books, naysayers, experience, television specials, etc. A survey of an organization’s culture regarding where respondents think the organization should be sustainability-wise would be very educational for all involved. The questions could serve to prompt thinking in respondents and could help the STF prioritize educational topics. After gaining insight into the organizational culture and current thinking regarding sustainability, leaders can provide a variety of educational opportunities. Those providing the education should strike a balance between sharing and discussing the big picture and helping people grasp what they can do on a daily basis to start working toward that big picture.

Ultimately, asking people to take ownership and engage in educational opportunities entails asking them to change – no matter how much. As such, the following four concepts may serve a STF well that is aiming to engage its employees: Gladwell’s (2000) Change Criteria; Theory of Zones; Zone of Proxinal Development (Vygotsky, 1978); and Change Conditions (Nalder, 1995).

Change Criteria

Gladwell (2000) asserts three change criteria: 1. the new (disruptive) information must come from trusted sources (e.g., consultants, the CSO, executive team, a friend, colleague, news source, etc.); 2. the prospective change result (of action and/or thoughts) must be within one’s moral code; 3. and the message must be reinforced (hence an aligned STF).

Theory of Zones

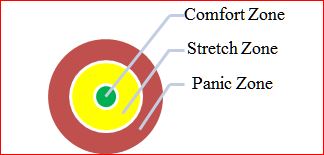

The field of experiential adventure education often employs the Theory of Zones when designing opportunities for people. The model, depicted in Figure 4, entails three concentric circles.

Figure 4. The Theory of Zones

The inner comfort zone is a familiar concept and tends to be where most operate on a daily basis. While learning can take place in the comfort zone, it is rather inconsequential and does not serve to change the individual. An example might be learning that the SunChips™ bag is compostable. The outer panic zone should be avoided, as it halts learning in the area of the particular topic and is detrimental. When some people start to learn about environmental and social issues, they often get bombarded with negative and depressing issues, such as the rate of rainforest destruction and species extinction, polar bears struggling to survive due to the fast pace of the glaciers melting, and the number of children who die from malnutrition when there are so many obese people in first-world countries; the list goes on. When people are not given tools to cope with this information, they can feel paralyzed, overwhelmed, and hopeless. In some cases, such people simply refuse to learn and continue to forge through life avoiding such issues. No significant learning or change occurs in the panic zone.

When aiming for education, ownership, and ultimately engagement, providing opportunities for people to engage in the stretch zone is key. In the stretch zone, people will experience disequilibrium (Piaget, 1970), for new information and actions do not align with the norm. However, a good support system and encouragement can serve as great motivators. Eventually, the disequilibrium abates and the comfort zone enlarges. The stretch zone is where profound learning takes place, for it challenges us and provides perspective. By definition, life-changing, long-lasting lessons take place in the stretch zone. Such learning can occur during a new project, while engaging in a new aspect of an on-going project, or as part of a professional-development initiative.

Zone of Proximal Development

Vygotsky (1978) offers the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD), which is the difference between what a person can achieve alone versus what can be achieved with the aid of a mentor. When engaging employees in sustainability initiatives, it is helpful to have an accessible CSO, expert consultants (e.g., energy), and/or STF members; these people can be mentors by offering help and support when needed. Investing in the education and growth of employees shows them that they are valued and can help them take ownership in the process.

Change Conditions

This final concept, born from experiential education, can aid the STF and/or consultants in designing stretch zone experiences programs that will aid in fostering EE. Nadler (1995) outlines six “Change Conditions”, which include Hope, Effort, Trust, Constructive level of anxiety, Sense of the unknown, and a Perception of risk. Consider these conditions integral to stretch zone experiences. Hope can come from the aligned STF, case studies of successful organizational sustainability initiatives, or myriad other sources. Effort facilitates garnering ownership, being open to education, and taking action. Trust grows via an aligned STF that has consistent messaging, and it can also grow via short-term adventure-learning experiences and other problem-solving initiatives. A Constructive level of anxiety entails challenging people to get them out of their comfort zone, but not overwhelming them, so as to push them into the panic zone. For example, a STF might share that the organization is embarking on an aggressive strategy to incorporate sustainability into its definition of success (cause anxiety), but also provide examples of attainable daily operations that will allow the company to achieve this type of success, as well as welcome people into the process (ease anxiety). Embarking on a new project assumes a Sense of the unknown, for even if someone has been at an organization that embraces sustainability, another organization with a different group of people will yield a different process and different results. Likewise, entering new territory can carry a Perception of risk, for the outcomes are unknown. Desiring a sense of the unknown and perception of risk are encapsulated in Ernest Shackleton’s 1914 advertisement in the London Times for his expedition to the South Pole; it read, “Men wanted for hazardous journey. Small wages, bitter cold, long months of complete darkness, constant danger, safe return doubtful, honor and recognition in case of success”. Thousands of men reportedly answered his advertisement. While today’s risks are significantly tamer, the need for adventure, risk, and testing ourselves remains. Takings risks entails taking action.

Action

While it might seem that employees taking action connotes engagement, this may not be the case. Perhaps the greatest difference between an employee acting and an engaged employee taking action is the motivation; it might be argued that employees going through the motions are motivated extrinsically, while engaged employees have intrinsic motivation. This model for employee engagement focuses on the latter.

Taking action requires a call to act, critical thinking, and problem-solving, for the actions need to align with the ISP. Problem-based learning is an effective approach for taking action while uniting an organization (or units therein) toward a common goal. A tactic that can help individuals gain awareness into their own actions and impacts, while taking action is to challenge them to increase their personal sustainability for a given amount of time. For example, we regularly charge (i.e., make a “call to act”) our Inquiry into Sustainability students at Western State Colorado University to make a personal sustainable change for at least one semester. One student vowed to buy no new clothes, which challenged her because she was a self-proclaimed retail therapy shopper. Others decided to either take the bus or carpool. Yet others canceled their junk mail and switched to online bill payments and are more conscientious about doing their recycling. Most begin to feel good about their small acts and start to influence their friends, parents, and communities. When they begin to realize that they can make a difference, we challenge them to work in groups to make a positive sustainable change within the University or in the broader community. This requires both critical thinking (e.g., figuring what needs to be addressed and prioritizing myriad options) and problem solving (e.g., how to approach the problem). Over the years, two different groups have worked with a local ski area to enhance its recycling program, conduct an energy audit on a hotel, and design an energy reducing pilot program for the hotel. Other groups have worked with a local restaurant to reduce its water and energy consumption, increase its recycling and composting program, start to produce its own food, and drastically reduce its waste. Another student wrote and a grant for a bus shelter because she thought if students could at least be partially protected from Gunnison, Colorado’s sub-zero winter temperatures, they might be more likely to ride the bus to the ski resort; she was right, and the town followed her lead to construct more shelters. Students in the class over the last two years have been working toward establishing a campus greenhouse as a means to decrease the college’s carbon footprint, while providing organic, fresh food in a location that has a 60-day growing season. Their impassioned engagement became contagious and more courses tackled other aspects of institutionalizing a campus greenhouse, showing solidarity among the students and sending a clear message to administration that a greenhouse is a priority. An aquaponics system that includes fish is currently being installed, and the student directors have been approved to sell greens and herbs to Sodexo.

Encouraging people to take action can be a small organizational investment, such as Werbach’s (2009) example of Wal-Mart’s employees’ Personal Sustainability Plans, which were similar to our students’ actions to minimize their own impacts. Or, organizations can make a bigger investment in employees taking action. For example, Patagonia employees can apply for a sabbatical to do service. Taking action and experiencing the emotional, intellectual, and social, benefits first-hand is a powerful practice that people tend to want to spread. Whether on a micro or macro level, taking action within or outside organizational walls becomes a stepping-stone for embarking upon larger initiatives, which can aid the successful implementation of an ISP.

Experientially Engaging Employees

The following strategies and suggestions focus on professional development initiatives that can be initiated by Human Resources, the CSO/Sustainability Director, STF, or consultants. There are myriad approaches to professional development, each of which has beneficial and less effective aspects, as well as varying levels of experientiality (e.g., awareness initiatives tend to require a low level of experientiality, while action requires a high level of experientiality). Various strategies, how they are being defined in this paper, as well as the corresponding benefits (denoted by +) and drawbacks (denoted by -), are in Table 1.

Table 1. Professional Development Strategies

| Memo | Electronic or hardcopy delivery sent with the intent of relaying company information. |

- (+) delivering key information to many people

- (-) people can become complacent about taking them seriously when they are overused

Short-term

In-services

Generally convened on organization’s property, whether on a regular basis or only when necessary. Cover a variety of topics, such as awareness about sexual harassment, persuasive writing, public speaking, business development, networking, and travel arrangements and reimbursement.

- (+) allows for relaying new mandates

- (+) relatively inexpensive (e.g., generally no travel)

- (-) ineffective means of cultivating ownership necessary for change

Short-term

Adventure

Simulations / Experiences

Entails intentionally engaging in custom-designed challenges together outside of work and generally off-site, as a means to refine interpersonal skills that will be needed when unanticipated and unwanted challenges arise. They can also be used to bring a divided community together. An example is a group partaking in a challenge course followed by food, drink, music, and socializing.

- (+) breaking down social barriers by having fun together and getting to know one another on a different level

- (+) engaging in stretch zone experiences that allow participants insight into their leadership and communication skills

- (+) enhancing group and individual team-building and problem-solving skill

- (+) can be part of a “rite of passage” in a corporation culture

- (-) ineffective facilitation regarding the transference of lessons learned from the experience/ simulation to work life can render the experience useless on a corporate level

- (-) if powerful lessons learned and behavioral change are not reinforced at the workplace, it easy for lessons to be forgotten and old behaviors to return

Long-term

In-service

Focused on consistent messaging and repeated opportunities to improve in a certain area (e.g., leadership, promoting sustainability). Generally spans 1-2 years with various workshops/components occurring every few months (e.g., 360° evaluation, Myers Briggs Type Indicators, executive coaching, custom-designed programs aimed at enhancing collaboration effectiveness).

- (+) often incorporates tips and practices to increase workload efficiency by actually applying new skills to daily work

- (+) reinforced messaging and engagement provide opportunities for change

- (-) does not necessarily provide stretch zone opportunities

- (-) people can be challenged to engage with the topic due to the proximity of their workload

There is no perfect strategy for all organizations, as the values, goals, leaders, and employees, among other aspects, are different. However, a mix of the strategies highlighted above is suggested, so as to reinforce messaging in a variety of ways, as well as addresses people’s myriad ways of taking in information.

Gardner (1983), a Harvard neuroscientist, set forth the Theory of Multiple Intelligences over 30 years ago, and it is widely used by educators to help guide teaching strategies. It bucks the notion that intelligence ought to be determined primarily by logical-mathematical and verbal-linguistic metrics. Set forth in Table 2 are the eight multiple intelligences identified by Gardner, as well as example goals (black bullets) that might help align people and strategies (hollow bullets) to help attain them. (It is important to note that Gardner does not advocate his multiple intelligences as teaching strategies, yet educators have found their guidance helpful.)

Table 2. Multiple Intelligence Strategies for Engaging People in an Organizational ISP.

| Intelligence | Example Sustainability Goals and Strategies |

| Visual-spatial |

o Image of plane and aluminum cans (described above)

o Water bottle 1/4 full of oil to show how much is used to manufacture and transport the bottle

o Watch two videos: one of child labor and unhealthy working conditions; and one of workers in working conditions are well-lit with natural light, clean air, rejuvenating breaks, etc.

o Watch a video of rain forest destruction and brainstorm strategies to reduce paper use and waste

|

| Naturalist |

o Recollect positive experiences in nature (even if it was simply walking through Central Park) o Tell stories of misadventures in nature and the role that the environment played that now bring laughter o Offer retreats in nature (e.g., hikes, white water rafting) during which brainstorm means of lessening environmental impact |

| Interpersonal |

o Listening tour (described above) o Play FishBanks™, a simulation that teaches about the importance of collaboration and responsible consumption of resources and social justice. o Brainstorm strategies for how each division can work toward attaining ISP goals / benchmarks o Work in teams to track environmental, social, and economic life cycle of a company product

o Establish a feedforward and feedback culture |

| Intrapersonal |

o Challenge people and/or corporate sectors to keep a week-long expenditures and task log and reflect on it o Challenge people to take on a personal resolution for X amount of time to decrease their negative environmental and/or social impact (e.g., only buying fair trade coffee and using a reusable coffee mug) |

| Linguistic |

o Provide ISP document to all employees, investors, and customers o Ask all employees to read all or part of Werbach’s (2009) Strategy for Sustainability or a host of other books / articles o Invite employees or investors to attend lectures, workshops, conferences and other events focused on SSP issues o Invite employees, investors, and/or consumers to submit ISP funding proposals for initiatives they’re passionate about and have a fund to support annual submissions |

| Musical |

o Start / end meetings with various social and environmental activists, such as Jack Johnson, Wyclef Jean, Michael Franti, Ani DiFranco, Rage Against the Machine, Public Enemy, etc. Be wary of violent or offensive language. |

| Bodily-kinesthetic |

o Welcome employees of X years to participate in a service project for regular pay for 1-4 weeks rather than go to work o Challenge employees to find an innovative way to help the corporation reach an ISP benchmark o Hold various competitions, such as walking, riding a bike, or taking public transportation to work |

| Logical-mathematical |

o Share stories and budgets of companies that decreased their carbon footprints and expenditures by driving a more efficient route (e.g., UPS) or minimizing packaging (e.g., Cisco) o Hold a competition (e.g., between various regions) to decrease phantom loads by first calculating baseline data |

Strategies like these can reinforce messaging, provide stretch zone opportunities for employees, and help them take action, among other positive outcomes – and ultimately increase engagement.

Conclusion

No matter what scaffolding, change concepts, or strategies are employed as a means of engaging employees, a reflective process is a critical tool for becoming ever more effective, whether that’s the experiential learning cycle (Kolb, 1984); Planning, Acting, Reflecting, and Refining (PARR) (Moran & Tame, 2012); or some other model. During the process of engaging employees and advancing sustainability – as well as after initial goals are achieved – it is important to remember that people like to feel appreciated. STF should take time to thank people or provide rewards (great or small) for their work, acknowledging particular acts. Engaged and happy employees are central to an organization’s integrated approach to sustainability and ultimate viability.

References

Chouinard, Y. (2005). Let my people go surfing: The education of a reluctant businessman.

New York: Penguin Group.

Dunn, C. (2007). Get a Green Job: GreenCareers by MonsterTRAK. Last accessed online on

9/30/2012

Elkington, J. (1998). Cannibals with forks: The triple bottom line of the 21st century business.

Gabriola Island, Canada: New Society.

Gardner, H. (1983). Frames of mind: The theory of multiple intelligences. New York: Basic

Books.

Gibbons, M., & Hopkins, D. (1980). How experiential is your experience-based program? The Journal of Experiential Education, 3(1).

Gladwell, M. (2000). The tipping point: How little things can make a big difference. New

York: Little, Brown, and Company.

Goldsmith, M. (2007). What got you here won’t get you there. New York: Hyperion.

Harter, J. K., Schmidt, F. L., Killham, E. A. and Agrawal, S. (August 2009). Q12 meta-analysis:

The Relationship between engagement at work and organizational outcomes. Gallup.

Hewitt Associates (2010). Best employers in Canada. Last accessed online on 9/18/2012

India Resource Center (March 2010). Coca-Cola liable for US$48 million for damages –

Government Committee. Retrieved on June 27, 2011, from:

http://www.indiaresource.org/news/2010/1003.html

Johnson Controls (2010). Generation Y in the workplace. Last accessed online on 9/18/2012

Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Linville, P. W. & Fischer, G. W. (1991). Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60(1), 5-

23.

McDonough, W. & Braungary, M. (2002). Cradle to cradle: Remaking the way we make things.

New York: North Point Press.

Moran, B. & Tame, P. (2012). Organizational Sustainability: Growing Leadership and

Resilience. Sustainability: The Journal of Record, 5(4): 233-237.

Nadler, R. S. (1995). Edgework: Stretching boundaries and generalizing experiences. Journal

of Experiential Education, 18(1), 52-55.

National Environmental Education Foundation & GreenBiz (2011). Toward engagement 2.0:

Creating a more sustainable company through employee engagement. Last accessed

online on 9/18/2012

Orr, D. (1992). Ecological literacy: Education and the transition to a postmodern world.

Albany: State University of New York Press.

Piaget, J. (1970). Science education and the psychology of the child. New York: Viking.

Savitz, A. (2006). The triple bottom line: How today’s best run companies are achieving

economic, social, and environmental success – and you can too. San Francisco: Jossey

Bass.

University of Wisconsin Continuing Education, Outreach and E-Learning (August 16, 2010).

Lessons from the Gulf: The American public believes business leaders need to be well-

versed in sustainability. Madison, WI: News Release.

Vygotsky, L. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes.

Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Werbach, A. (2009). Strategy for sustainability: A business manifesto. Cambridge, MA:

Harvard Business Press.

[i] [10] An integrated strategic plan is one that holistically attends to social, environmental, and economic aims. A non-integrated approach would entail an organization having a general strategic plan (usually focused on economics), an environmental sustainability strategic plan, and a corporate social responsibility strategic plan.

[ii] [11] Ideally, a sustainability task force will be comprised of people from throughout an organization, including those from the Cabinet/C-Suite, middle managers, entry-level individuals, students/customers, custodians, finance, human resources, Board members and/or investors, et cetera.

[iii] [12] Moran and Tame (2012) published a simpler version of this model, though the three steps for Action were not included, as the thrust of the article was on resilience.