Table of Contents: JSE March 2015 — Sustainability: What’s Love Got to Do with It? [2]

PDF: Clingan JSE March 2015 Love Issue [3]

Abstract: This opinion/editorial presents the belief that love is present in all human lives as an emotional experience and may be present in all human lives as an intellectual idea as well. It considers possible actualities that lie behind some common thoughts (clichés) about love. The author presents the idea that even though love is central to our lives, the word love, if not the concept of love, is avoided in academic discourse. The author explores some of the scholarly, theoretical, and philosophical writing about love, noting that it is often named something other than love (compassion, well-being, altruism, etc.). The question and invitation are presented to consider what might be possible if love were intentionally and specifically identified as a methodology, pedagogical practice, and value in leadership, activism, and education.

Keywords: love, pedagogy, leadership, transformation, social justice, sustainability

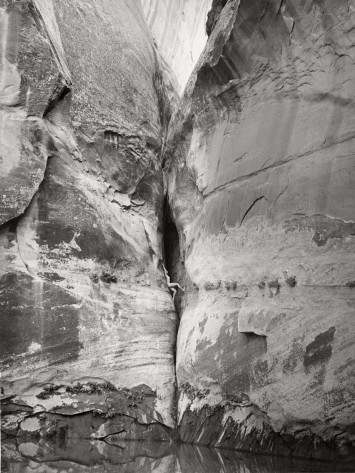

Note about the photography: The black and white photograph that is the link to this article was taken of Katie Lee [4] in Glen Canyon in 1957 by Martin D. Koehler; used with permission of Katie Lee. Aspen photos are by Rich Lewis; used with permission.

A Pedagogy of Love

Consider for a moment that love—or a connection to love—is the one singular thing that every human on this planet has in common. Each of us has at some point loved or been loved, celebrated love or longed for love, thought about love or doubted our understanding of love.

Some of us have done all of that and more. From the perspective of feelings and emotion, I believe that every human has some connection to the concept of love. Whether one lives a very short lifetime surrounded by people who feel great love for them or lives a long slow life of longing for some unattainable sense of what love could be, I suggest that all humans have what we might call an emotion- or heart-based connection to love. Beyond simply having some sense of it, I believe that love—having it, finding it, engendering it, or losing it—is central to human existence on this planet. Our stories tell us this, our art is inspired by love, and our music tells us that love is everywhere. From songs to slogans, clichés abound that tell us love is the answer, love can heal all things, and love is all we need.

In addition to the very human condition of having an emotion- or heart-based connection to love, we humans also have a tendency to wax philosophical and consider the meaning of love. I imagine that wanting to understand love from a mental or intellectual perspective is nearly as common as human desire to experience the feelings of love. When seemingly cliché ideas that love is all we need are taken further, they become theories about the practical importance of love. For example, I first heard from one of my graduate professors that no matter what the question, the answer is love, and from another I was taught that whenever a person asks for something from another, what they are truly asking for is to be loved. Similarly, in the spirit of Martin Luther King’s words, many mentors and teachers suggest that only love can truly heal and only love can generate more love. Myriad ontological perspectives evolve from ideas presented in some of our earliest literature, from Plato’s work to the Bible to the Qur’an, that suggests that the root of human motivation is love. I like the way Maya Angelou puts it in an interview: “Love is the most powerful element in the universe. It may in fact be the thing which holds stars in the firmament and that thing which keeps the blood rushing in our veins.”

In spite of the ready presence of this thing called love in our daily discourse, and in spite of the fact that much of our very existence is founded on texts that center on the importance of love, pinning love down to something tangible and definable remains a challenge. Considering love as a topic for scholarship presents an even greater challenge. In Earth in Mind David Orr writes, “Except as pejoratives, words such as emotional bonds, fight, and love are not typical of polite discourse in the sciences or social sciences.” Orr’s work goes on to explore ways we might reconcile values, love, and knowledge, yet overall love as a topic of scholarly discourse continues to be evasive. Or is it? Is love in fact present throughout the writing and thinking that people do related to positive change and growth? Is it simply time to call it love and prioritize it as a motivating value and methodological approach? I believe that love is present and that scholars, activists, leaders, educators, artists, and anyone trying to effect change needs to acknowledge the presence of love in our work. Collectively it is time to imagine and realize what is truly possible if love were to unambiguously inform our thoughts and actions.

My interest in love and the heart is not exceptional. As I believe is true for all humans, the desire to love and be loved is unequivocally central to my existence on this planet. I am enthusiastically enjoying an adventure that has taken me into times of great despair over what I believed was the inaccessibility of love, and into times of great joy for the abundance of love that exists in my life. As I imagine is true for many of you reading this, I wholeheartedly seek to keep the former experience behind me as much as possible and to live a life that is blessed with an ever increasing experience of the latter—an abundance of love and joy. I don’t imagine that my interest in understanding love in order to more richly experience it is unusual either. I wonder how I’m doing, how well the love I feel is received, and what I can do to have love more consistently lead my thoughts and actions. Where I may have something to add, and the vision that has led me to this work on love and sustainability, is that I believe that love—specifically named as love—belongs in every curriculum, every law, every strategic plan, and every mission statement. I believe that if we humans move beyond the feeling and the fears about love, stretch our minds past our wondering about love, and take our greatest philosophies and thoughts about love to a consistent practical application, that we will see healthier communities that are filled with and sustained by love. More than suggesting that we incorporate love into the curriculum, I would say that the human curriculum is love.

I began to explore scholarship and philosophy about love in order to consider how I might incorporate love more specifically and precisely into my own personal pedagogy and thus my work as an educator, an activist, and a writer. I thought that my teaching might benefit from pulling together a quick overview that highlights literature on love specific to activism and social movements. I knew that I would have to consider Plato’s Symposium of course, and Erich Fromm on The Art of Loving, and I assumed I would then move right on to everything by Gandhi and Dr. Martin Luther King. Straightaway in my review I was impressed by the great amount of work that has been written directly about love, but more I was happily overwhelmed as I began to recognize that in some way everything that is written about change, transformation, or justice is about love. Even ideas that seem to stand against love feel to me to be a cry for love. I came to ask myself whether anything other than words of love could exist and began to wonder if it is true that no matter what the question, the answer is love. I have come to believe that surely the only question humans ask is how we can ensure greater love.

Ideas and words of love fill literature, from great tomes about The Ways and Power of Love (Sorokin), to simple ideas mentioned in passing while exploring the theory of evolution, such as the insight that the love for all living creatures is the noblest attribute of humanity (Darwin). Why then, given that philosophers and leaders have been examining the meaning of love since the beginning of recorded human thought, is the inclusion of love in scholarly work still evasive? And if my premise is true that love is embedded in every text, every idea, why do we not simply call it love? Why do we offer degrees in peace studies and justice studies, even happiness studies, and not have academic programs in love studies? I do not want to attempt to answer this question; rather I want to change the practice. (Besides, Wikipedia contributors already figured out that the “diversity of uses and meanings combined with the complexity of the feelings involved makes love unusually difficult to consistently define.”) I understand that the concept of love can be evasive and unattainable, perhaps in a way that no other concept is. I also know that we manage to navigate other terms that are ambiguous. Consider, for example, the ongoing public and academic discourse around the meaning of social justice; yet we have laws that are built on an historical foundation to ensure justice, academic programs that teach social and environmental justice, and movements that celebrate and fight for justice. People may continue to argue about the definition of justice, and like love some people will scoff at the esoteric nature of the term, but those who work toward justice know that they share a common vision that can be attained and measured. They know that justice is worth fighting for until the eternal victory (¡Hasta la victoria siempre!, Guevara).

I feel equally certain that there are also those who dedicate their lives and work to increasing the presence of love and to encouraging love as a motivation for thought and action, and often, those people come from a spiritual or religious position. For example, the Dalai Lama writes that love is fundamental to the continued survival of our species. My graduate studies focused on understanding psychology and spirituality as a path to healing. It centered on the work of Carl Rogers, who presents unconditional positive regard (in other words, love) and Fritz Perls, who reminds us that how we relate or respond to the issue is the issue (in other words, respond with love). What I believe is needed is more direct conversation about love as a specific methodology that guides discussions in academic, business, and legal settings, and more awareness and celebration of the conversations that already exist.

The majority of my own research and learning is in the field of twentieth century US literature; I have always struggled to find the simplest way to describe what I was looking at and for in literature, and I ultimately called it justice-based literature. I studied work by those who write about ending oppression and injustice, and the people whose work I have been most drawn to are those who write about love. James Baldwin, for example, writes about systemic racism and the need for change and yet in a response to the Supreme Court decision in Brown versus the Board of Education, he wrote that had it been a matter of love the decision would have happened much sooner. Martin Luther King Jr.’s writing is transparently about love. As a minister inspired by the work of Gandhi, King addressed love in much of his writing. In fact as I look back on the scholars/writers who most informed my own doctoral research, I notice that many of them are people of color writing about race and the need to end racist thinking and systemic racist practices. bell hooks writes All About Love through multiple books that specifically speak to the connection between love and equality or justice. hooks and Cornel West wrote Breaking Bread, which directly connects love and social justice. Paolo Friere writes that love is the foundation of dialogue and praxis/action. I am proud to have my scholarship stand on some very impressive and loving shoulders. My methodological approach for my dissertation is a contribution to critical social theory called solidarity theory, which deconstructs supremacist ideology in favor of holding unconditional and equal value and respect for all human life (in other words, love). Whether it is related to race, class, gender, sexual orientation, nation, language, or any other aspect of human identity, work that focuses on human liberation and the exposure and elimination of supremacist thinking related to identity is dependent on love. I believe that thoughts and actions based on love for our fellow humans inherently and unconditionally honor who they are. A solidarity-based approach asks that in addition to the important work we do to bring awareness to and end singular supremacist ideologies and practices (sexism, racism, heteronormativity), that we also work in solidarity across those communities to bring love and respect to all human life.

In other areas where I teach and do research, including sustainability education, transformational leadership, transformative learning, social justice, and the arts and humanities, work related to love is very present, though it may not always be called that. This thing called love is often called anything but love—well-being, happiness, presence, respect, equality, liberation, ethic of care, altruism, prosocial behavior, positive psychology, compassion. When I consider the resources I use in my work, I see love everywhere. Brené Brown notes that in being vulnerable we cultivate love. The concept of presence, as taught by Senge, Scharmer, Jaworski, and Flowers, is about taking a breath, centering in the heart, and ensuring that we speak and act from a place of love. Jack Mezirow asks us to unreservedly engage with those who are different from ourselves in order to engender a transformative learning experience. Seligman and Haidt remind us directly that love creates happiness. Peter Gabel’s work aims to create a culture of spirituality and love in the legal world. Many writers who explore our natural world stand on a foundation of love. David Orr writes that those of us who act in service to the natural world do so because of deep resonance with (love for) the natural world. Stephen Jay Gould tells us we can only fight to save that which we love. Anna and Francis Lappé give us hope to transcend consumerism and feed the world. Terry Tempest Williams’s work on place and family connects the two through love. Goodness, if I start naming feminist theorists this essay would never end, but consider for a moment Toni Morrison, Nel Noddings, Margaret Wheatley, Patricia Hill Collins, Chela Sandoval. June Jordan directly declares that love will “carry action into positive new places.” The list goes on.

Sometimes, even when scholarship on love is called scholarship on love, we somehow still manage to silence it. In 1954 scholar activist Pitirim Sorokin wrote a hefty scientific analysis of love called The Ways and Power of Love. He touches on many ways that love can transform, including economics, mental and physical health, and the sustainability of community health. Here’s a short bio of Sorokin that is on book store pages that advertise his book:

Pitirim A. Sorokin (1889-1968) was a controversial figure in twentieth-century sociology, and a pioneer in the scientific study of unlimited love. He served as the founding chairman of the sociology department of Harvard University. He was interested in discovering more about how love for others is related to felt participation in a Presence that is higher than our own and that serves as a source of unlimited love across all divisions of religious, political, and ethnic loyalties [emphasis added].

This bio makes very clear that the focus of Sorokin’s scientific scholarship is love. And yet the Wikipedia biography of Sorokin does not include the word love even one time. It is hidden behind all of the other words that are acceptable in academic discourse. I find myself more surprised than disappointed when I make efforts to fold a pedagogy of love—called love—into the curriculum. I am intrigued by pretentious faces of academics who suggest that love is too vague, ambiguous, groovy, emotional, or inexplicable to be scholarly. But those experiences seem to be declining as the expression of love sustains a strong presence in scholarship and more scholars are willing to claim love as their methodology.

I turn my attention to celebrating successes and moving forward with trust that there will be many more of them. When a group of colleagues recently decided that we want to create a global continuing education program about transformational leadership, we began by considering how to support women’s approaches to leadership and how feminist methodologies define leadership values. During one of our many conversations about what we were calling feminine and feminist approaches, I asked my colleagues if it was true that the values we were talking about all come back to love.

The response was what I dream of. We ultimately named our institute for what we strive to practice—loving leadership. In my work with graduate students there is always a lot of interest when I talk about love in the curriculum. I am delighted that so many students have stepped forward to explore ways to fold love into their scholarship about justice, sustainability, the arts, leadership, and transformative education. I hold the vision of love becoming a fundamental methodology in all academic fields and I hold a vision that is very personal and powerful about what that could mean to our planet and all life on it. Even here I find myself hesitant to state it. A stated belief that love can heal the ills of the world is still called out as Pollyanna and naïve. But I say it anyway—I believe with certainty that when we act from love the results transform for the good. With love our laws can change, our systems can change, and we can in fact begin to heal the world.

I am especially and extremely grateful for the enthusiastic commitment that my colleagues Chiara D’Amore (yes, of love) and Betsy Wier have to the position that love has in our work. That commitment results in this issue of The Journal of Sustainability Education. We present the JSE love issue as our invitation to ask yourself what love has to do with your work. We know the answer for us. Everything.

LOVE

Love is an action, never simply a feeling. — bell hooks

HOPE

Hope is a verb with its sleeves rolled up. — David Orr

PEACE

Peace is not merely a distant goal that we seek, but a means by which

we arrive at that goal. — Martin Luther King, Jr.

References/Suggested Reading

Angelou, Maya. (2004). The collected autobiographies of Maya Angelou. New York: Modern Library.

Baldwin, James. (1998). Collected essays. New York: Library of America.

Baldwin, James. (1963). The fire next time. New York: The Dial Press.

Brown, Brené. (2010). The gifts of imperfection: Let go of who you think you’re supposed to be and embrace who you are. Center City, MN: Hazelden.

Clingan, Joan. (2008). Who is we?: Toward a theory of solidarity; toward a future of sustainability (doctoral dissertation).

Hill Collins, Patricia. (2000). Black feminist thought: Knowledge, consciousness, and the politics of empowerment. New York: Routledge.

Dalai Lama. (1962). My land and my people: The autobiography of His Holiness the Dalai Lama. Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

Darwin, Charles. (1871). The descent of man, and selection in relation to sex. London: John Murray, Albemarle Street.

Friere, Paulo. (1993). Pedagogy of the oppressed: New revised 20th anniversary edition. New York: Continuum.

Fromm, Erich, & Anshen, R. N. (1956). The art of loving. New York: Harper & Row.

Gabel, Peter J. (2013). Another way of seeing: Essays on transforming law, politics and culture. New Orleans: Quid Pro Books.

Gandhi. (1957). An autobiography: The story of my experiments with truth. Boston: Beacon Press.

Gould, Stephen J. (1993). The book of life. New York: W.W. Norton.

Haidt, Jonathan. (2006). The happiness hypothesis: Finding modern truth in ancient wisdom. New York: Basic Books.

hooks, bell. (2000). All about love: New visions. New York: William Morrow.

hooks, bell. (2001). Salvation: Black people and love. New York: William Morrow.

Jordan, June. (2002). Some of us did not die: New and selected essays of June Jordan. New York: Basic/Civitas Books.

King, Martin Luther, & King, Coretta Scott. (1983). The words of Martin Luther King, Jr. New York: Newmarket Press.

King, Martin Luther. (1963). Strength to love. New York: Harper & Row.

Lappé, Frances Moore, & Lappé, Anna. (2002). Hope’s edge: The next diet for a small planet. New York: Jeremy P. Tarcher/Putnam.

Mezirow, Jack. (2000). Learning as transformation: Critical perspectives on a theory in progress. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Morrison, Toni, & Denard, C. C. (2008). What moves at the margin: Selected nonfiction. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi.

Noddings, Nel. (1984). Caring: A feminine approach to ethics & moral education. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Orr, David W. (2010). Hope is an imperative: The essential David Orr. Washington, DC: Island Press.

Orr, David W. (1994). Earth in mind: On education, environment, and the human prospect. Washington, DC: Island Press.

Perls, Fritz. (1969). Ego, hunger and aggression: The beginning of Gestalt therapy. New York: Random House.

Plato, Groden, S. Q., Brentlinger, J., & Baskin, L. (1970). The symposium of Plato. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press.

Rogers, Carl. (1951). Client-centered therapy: Its current practice, implications, and theory. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Sandoval, Chela. (2000). Methodology of the oppressed. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Seligman, Martin. (2002). Authentic happiness: Using the new positive psychology to realize your potential for lasting fulfillment. New York: Free Press.

Senge, Peter, Scharmer, Otto, Jaworski, Joseph, and Flowers Betty Sue. (2005). Presence: Exploring profound change in people, organizations, and society. New York: Doubleday.

Sorokin, Pitirim A. (1954). The ways and power of love: Types, factors, and techniques of moral transformation. Boston: Beacon Press.

West, Cornel, & hooks, bell. (2000). Breaking bread. Sound recording.

Williams, Terry Tempest. (1992). Refuge: An unnatural history of family and place. New York: Vintage Books.

Wheatley, Margaret J. (2010). Perseverance. San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler.

Wheatley, Margaret J. (2009). Turning to one another: Simple conversations to restore hope to the future. San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler.